Disclaimer: This review entails racist content and imagery with the intended use of historical and informational context. I ask that you speak up in the case I say something that is offensive, harmful, or perpetuating so that I may take the appropriate accountability. Thank you

Release Date: November 22nd, 1941

Series: Looney Tunes

Director: Chuck Jones

Story: Chuck Jones

Animation: Bobe Cannon

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Porky, Ant)

(You may view the cartoon here.)

There’s something rather fitting about Chuck Jones’ last short of the year serving as a retread of an earlier short. It certainly is convenient for comparing his growth over the year—which impulses he has subdued or built upon, how his tone has changed, what he wants that tone to be, investigating how he balances his cartoons.

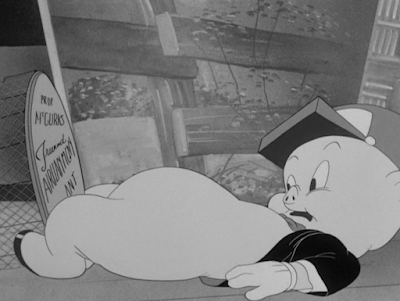

Thus heralds Porky’s Midnight Matinee: a casual continuation of Porky’s Ant. Like Ant, Matinee is largely dominated by pantomime, broken only occasionally through dialogue when necessary. Also like Ant, the ant resumes his role as a sprightly little heckler—much to the chagrin of theater manager Porky. Closing up for the night, he is duped into letting the little ant loose from his cage residing backstage, which proves to be particularly troublesome when discovering the ant has a hefty price tag that translates to an even heftier fine when lost. Especially given that the ant doesn’t seem too keen on being reunited with his cage.

Jones’ cinematographic impulses can be seen as early as the opening titles. Whereas most title cards exist only to brief the audience on the who and the what, often detached from the cartoon itself, the pompous, sweeping orchestrations of “You Oughta Be in Pictures” atop the lights in the theater going out immediately establishes a powerful ambience through such interactive elements that immediately draws the viewer into the cartoon. Especially given that most cartoons would open with the opposite: lights buzzing to life at the promise of a new day or shift, with the audience welcomed to enjoy first dibs.

A sense of intimacy dominates the opposite. Almost like a polite sense of trespassing. Staggering the times in which the lights go out (first the windows and main theater sign, then the marquee, then the lightbulbs beneath the marquee and then those stretching into the theater) likewise induces an organicism that benefits the aforementioned observations of intimacy and directorial sincerity.

After the camera has been acquainted with the actual title credits, the background painting shifts ever so slightly to indicate that the lights have gone out over the sign, too. The change in value is a bit more subtle than intended, lessening some of the clarity, but is nevertheless clear enough to communicate as a clever, interactive touch and topper. It’s a great consideration of detail on Jones’ behalf.

Formal introduction of the cartoon is a bit more humble in comparison to its opening—such is exactly the point. Manning the switchboard and shutting off all the appropriate lights, our perky theater manager bridges the gap between the titles by singing his own accompaniment of “Pictures”. Attuned ears will note that Porky’s orations are in the key of B#, whereas Stalling’s musical accompaniment of the same song is in C. Such concocts a slight dissonance that first registers as asynchronous and out of tune to the audience.

While it very well could have been an oversight, this disconnect renders Porky’s singing all the more naturalistic and humble—as has been evidenced in prior cartoons, he isn’t necessarily the type to burst into song with the same musical brazenness (or, less politely, talents) as a Broadway performer. To do so otherwise would feel wrong. He boasts a unique endearment to his periodically asynchronous vocals that Jones knew to capitalize upon here. Purposeful or not, the half-step gap between both orchestrations embraces these idiosyncrasies wholeheartedly.

Knowing that the audience may want to laugh at more than Porky being Porky, Jones slips a split-second bit of timing in which Porky flips one additional switch just after he’s expected to be done. It isn’t exactly a riotous gag by any stretch of the imagination, but is sharp enough in its timing to read as a subversion.

That all said, Porky’s singing lingers on just a bit longer than necessary. Showiness on behalf of the camera movements is a greater culprit than the actual act of Jones sustaining that little idea—the camera repeatedly pans back and forth to match Porky’s steps as he struts in place. A very considerate touch, but one that halts any momentum present just a bit too much. It seems a bit disconnected and choppy. Thankfully, there isn’t much present to disconnect nor chop to begin with, rendering it a very minor critique.

Especially given that this semi-continuous camera panning results in a change of narrative pace: quick, hushed “psst!”s off screen seek to overthrow the pacing in a manner that is much more purposeful.

Pan right (and in) to reveal the source of the noise: an ant trapped within the confines of a birdcage. His design has virtually remained the same. Same bone in the hair, same grass skirt. Both aspects read even more uncomfortably than divorced of their initially uncomfortable context, but nevertheless.

The biggest change manifests in desire. Whereas in Ant, where his goal was to avoid Porky and his motive of bug hunting, the ant here deliberately seeks his attention and calls him over. Of course, the giant metal cage is an easy indication as to why he would ever desire Porky’s involvement.

Porky doesn’t catch on as quickly. Shot at an up-angle, the layout cleverly communicates an oxymoronic sense of authority and lack of it all the same. Having Porky peer down at the viewer—a temporary stand-in for the ant—accentuates his superiority, in that he’s the only one who has the power to give him the necessary help. To the ant, he is a figure of authority in that regard.

To us, however, and to him, that isn’t as true. Subliminally commenting on his clear obfuscation, the layout positions him to the bottom of the screen. So much so that part of his body is cut off when he moves at certain angles—particularly when he tilts his head in naïve obliviousness. While he has the reigning authority over the ant, cutting him off and placing him away from the immediate center invites a rebuttal of that power, that authority. He doesn’t command the staging. Instead, he’s somewhat pushed into a role of agency unwillingly, and isn’t exactly sure how to navigate it… much less realize he has this role to begin with.

An action somewhat lost amidst the wires on the cage, the ant adjusts his skirt. It’s a certifiably Jones-ian maneuver—such a little adjustment indicates an ego of sorts, as if the ant feels he has to make himself presentable for the offer he’s preparing to forward. Porky’s body likewise doesn’t entirely fit within the confines of the camera to both make the ant feel smaller and him bigger: thus, the role of the ant as a powerless underling is furthered. Shading runs along Porky’s contours to exacerbate the above observations of his comparatively imposing solidity.

The cut to Porky’s face gawking in vacant confusion as the ant signals for him to follow probably isn’t necessary. Yet, like most things, is a relatively harmless addition and understandable as to why it would be included. What little momentum is present does momentarily stall, and Porky’s confusion has already been made relatively clear—regardless, it’s a way for him to endear himself to the audience and filmmakers alike and eliminate any concern about the ant dominating the spotlight. That, and his amalgamated hesitancy and befuddlement is convincingly portrayed through cautious head tilts, blinks, and other pauses.

After the ant signals for Porky to open the door, he finally receives the hint. Animation of him abiding is conducted with an almost disarming amount of gentility—the tactility and lack thereof, accounting for the diminutive size of the cage and ant, is very much felt. Slow, sweeping movements and gentle pressure that doesn’t openly read as lugubrious, mainly thanks to the lack of climactic action leading up to such a moment. If Jones were to remake the same cartoon 10 years later, this entire introductory routine would have tripled in speed. Thankfully, Jones has the right to take his time here, as there isn’t a nagging impulse to do otherwise.

That comes after. These gentle, crawling movements and impulses serve to juxtapose against the violent scramble that soon ensues as the ant makes a mad dash for it. Granted, said mad dash spends a little too much time on the wind-up, but the shift in demeanor and speed is certainly successful in its impact. Especially given that Porky is completely bowled over by the ant in the crossfire.

A bowling over that proves necessary in order to ogle at the bottom of the cage, which thereby presents the stakes offered by the cartoon. If the ridiculously specific—and just plain ridiculous—price tag wasn’t enough to politely amuse the audience, then the additional topper of “plus sales tax” cements everything together. It’s a clever way to introduce a real threat that the short must abide by, but to take the edge off through some of the absurdity. Having a sense of humor is always a must.

Brief technical note: the cage appears to be floating in mid-air. Porky is positioned ever so slightly on a different plane in the foreground, with the floor implied to be where his body comes in contact with it off-screen. However, the cage acts as though it is resting perfectly on the floor—if this were true, it would be positioned lower between Porky’s legs. This floating cage is likely a compromise for the sake of clarity. Indeed, the information on the bottom of the cage registers with greater immediacy than its physics (or lack thereof). In any case, it certainly proves intriguing to note and difficult not to when noticed. It’s a cheat, but a cheat that works.

Framing of the adjoining scene isn’t as immediate in its own clarity, but that is owed to other directorial obligations. Positioning Porky so low at the bottom of the screen at the start allows for his incredulous eruption ("One hundred an' sixty te-eh-te-eh-two million, four hundred an' twenty te-eh-teh-eh-two thousand, five hundred an' eh-thee-ehh-three dollars an' fifty-one cents!") to feel as big as it sounds. It isn’t exactly an eruption—he speaks at a reasonable volume—but the ferocity of his incredulousness is a stark contrast to the short’s domineering adoption of pantomime. Any dialogue is sacred. This, especially so, and boasts the theatrics to prove it.

Bobe Cannon seems to be the animator behind Porky’s rapid head tilts, given that they are a known trademark of his—it would certainly justify Porky’s more Clampett-esque appearance in this scene and the next adjoining handful.

This short is yet another vehicle for Jones to experiment and play with perspective. Obvious avenues are present, such as magnifying the scale of props and the overall composition to see the world from the ant’s point of view—a continuing indulgence from this period of directing. Likewise, there are opportunities to invent further beyond standard magnification and staging trickery. Experimenting with perspective includes the resulting camera pan as it slides up a long, tall rope, said rope growing wider and wider as the camera scales higher to indicate that it’s likewise getting closer.

Thus, the resulting ant lounging on the ball of knots is clear and coherent to the viewer in a manner that isn’t disruptive or erroneous. In other words: it’s a great way to make him clear to the viewer without feeling like a major cheat. The maneuver is convincingly dizzying.

Our star ant proves to be another student of the Bugs Bunny philosophy. His insulting nonchalance is the most obvious takeaway—the relaxed pose as he leans against the rope indicates it was no skin off his back, luxuriating in his confidence and happiness. A stark contrast to the sinking anxiety gradually grappling Porky of letting this price tag get away. Likewise, there is something to be said about the ease and convenience in which the ant is able to scale such a vast height in such a short amount of time. Audiences are encouraged to chew on the notion that Porky won’t share this same supernatural ability.

Jones purposefully clinches that notion by having Porky trip over—and into—a spare costume trunk. While toppling into the trunk, having the lid seal, and said trunk landing right-side up are all a bizarre combination of luck and implausibility, the sheer act of tripping over something is human. Grounded. It’s a vulnerability and reminds the viewer that these characters are subject to real human errors and impulses. Humans trip. Humans do not scale up ropes at impossible rates of speed. By tripping into this trunk, Porky is yet again cast as the underdog through his bumbling obligation to real world physics. He and the ant are on an entirely separate plane of physical boundaries.

As convoluted as this act of tripping, trapping, and toppling over right-side up is, the animation is conducted seamlessly. The entire charade is animated on ones, prompting Porky to disappear into the trunk in a flash; this could be seen as a detriment to the clarity, but his sudden disappearance and continued movement on the trunk as it rolls forward allows the audience to piece together what happened. Such is likewise a refreshing exercise of speed and ferocity on Jones behalf, which, as some of his shorts have a tendency to prove, can be a great novelty. Clarity is sacrificed momentarily, but works to the betterment of the gag.

Especially when considering the juxtaposition of the trunk coming to a halt; the slow burn of the reveal—Porky wearing a top hat and looking just a bit too coyly into the camera—makes a palpable change in demeanor with such wildly different pacing back to back.

Porky’s sly grin is a bit unnecessary, exemplary of Jones’ pet indulgences at the time, but is ultimately harmless. Ditto with the camera trucking in on the reveal and only to pan out seconds later—this movement reads restlessly and a bit unconfidently, but is understandable in its attempt to call attention to this new development.

That, and the rabbit wouldn’t fit within the confines of the screen if it stayed so close.

Having the rabbit’s ears move in a slight bit of follow through, interacting with where Porky’s hat slides off, is yet another incredibly considerate detail on Jones’ behalf. It gives the rabbit a larger permanence that is especially important for the sake of the gag. No, this isn’t an illusion. Porky is the own oblivious, unwilling recipient of his unintended magic trick. Nonplussed vacancy in his expression is conveyed well. Jones gets extra bonus points for the design of the rabbit, which is notably removed from the same anthropomorphism adopted by Porky, allowing a greater contrast and believability in the magician-and-his-rabbit hierarchy.

All of this tomfoolery results in a live laugh track from the ant. Drybrush peppers his movements and gestures in a way that is a bit needlessly bombastic, but nothing that completely drowns the action. It maintains the energy that, once again, exists as a large antithesis to Porky’s brewing befuddlement and comparative slowness.

Slowness that proves to be momentary as he chases after the ant. Walking on his hands is certainly a very Chuck Jones thing to do—not because Chuck Jones is renowned for his cartoon handstand antics, but because it’s such a randomly indulgent and needlessly extravagant action. Like Porky’s foray into the trunk, a clear vulnerability is communicated in how long it takes for him to properly scramble to his feet and get right side up. Priorities of pursuing the ant are first and foremost, to the point that he’ll engage in physiological impossibilities as a compromise. Even if he’s started on the wrong footing, that’s still footing that will get him one step closer to the ant one second quicker.

Once again, Bobe Cannon’s hand is particularly noticeable in how comparable his design is to Clampett’s Porkys of the late ‘30s; especially the 3/4s views or when he’s visibly scowling.

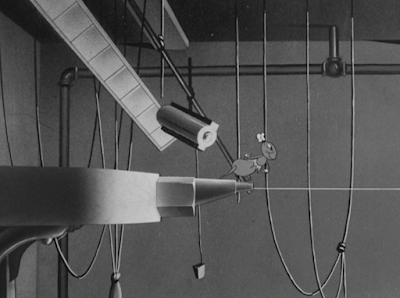

This, in turn, opens another avenue for Jones to indulge in the warped scale of the cartoon. Experimenting with the scale often results in a transformative atmosphere, and one that is often susceptible to cultivating a whimsy and energy particularly in line with Jones’ tastes of the era. The ant grabbing a wire and swinging onto a ledge is presented as a grandiose act of trapeze mastery—in reality, the act is so small that no human being would ever think to notice or pay attention.

Despite somewhat wearing out its welcome, the gag scratches Jones’ itch for the aforementioned reasons. The ant swings just a little longer than what is probably ideal, with the camera occasionally feeling as if it is continuously chugging forward rather than serving as a casual bystander. Regardless, long or short, this too is harmless. Having the ant swing through “hoops” concocted by the ropes hanging from the rafters is a clever way to ground the surroundings back to reality (this is the backstage of a movie theater, not a circus) while making a point not to discredit the ant’s showboating.

That honor is specifically reserved for Porky, whose brooding scowl informs us of his own intentions.

A camera fade to black marks a segue to the next scene; the comparative softness of a cross dissolve probably would have been more successful, in that a fade to black conveys a brusqueness that isn’t in demand. The fade merely lifts back up on the ant, still locked in the same position, his head cocked to indicate he’s watching Porky make his exit. Fades to black convey a passage of time—a mere translucent dissolve (or even a cut) would accomplish that same passage of tone without subliminally instructing the audience to expect more.

In any case, particulars are particulars. Chuck Jones’ directorial intentions lie with entertaining both the audience and himself: to accomplish that, he prompts the ant to gallivant across a tightrope.

Seemingly an innocuous action, this sequence dedicated to Porky pursuing the ant along the tightrope is one of the most solid pieces of filmmaking in the cartoon—it explicitly constructs a parallel that is given a satisfying tangibility, both in the ways the characters maneuver the same obstacle and how the music is reflective of their demeanor. Stalling’s score of “Java Jive” is light, airy, sprightly in conjunction with the ant. With Porky, the music retains its mirthfulness and charm, albeit at an octave lower to communicate his much larger weight (and disgruntled demeanor) next to the ant.

The camera is maintained at the exact same registry when panning back to greet Porky. Such directorial “neutrality” stresses how large and imposing he is against the ant, as well as how small and potentially inconvenient these obstacles are for him. The animators especially do a great job of making his presence feel permanent, imposing, and tactile; viewing the animation, the audience really does get the idea that Porky is genuinely interacting with his environments. Even folds are drawn on his skin where his cheek momentarily rests against the shoulder as he crawls upward.

Likewise, the tightrope noticeably buckles and bends beneath his weight—a much different interaction than the minimal blips and and flinches of the rope beneath the ant. Such is especially realized in the adjoining shot of him approaching the ant, his movements hyper and full of pent up energy as he charges forth. It’s very clear from his movements alone that he he’s on a mission. The outstretched, clawed hands as he marches forth, as if holding onto the air for support and communicating that the ant will soon be in those clawed hands is both a great acting decision and great way to uphold the momentum of the walk cycle. Stalling’s musical accompaniment grows more layered and obligingly forceful to match this change.

It moreover accompanies the mere movement of the rope as much as it does the demeanors of the characters. Panning back to the ant, whose hand is outstretched in an ambiguous signal of “STOP”, the bouncing on the rope gradually recedes to indicate Porky’s halting movements. Thus, the music does the same, its bouncy rhythm slowing at the same rate of speed as the rope. All of these factors read incredibly fluidly and coherently, and is a brilliant piece of directing. Camera pans flow together smoothly and coherently, the animation is successfully hypnotizing, and Stalling’s orchestrations give characters and environments alike an identity.

With the momentum coming to a halt, Jones now intends to completely disrupt any idea of momentum at all by having Porky look down (per the ant’s instructions). Looking down, of course, prompts poorly repressed anxiety, which prompts wobbly movement and larger room for error. The free-flowing smoothness in the scenes prior are proudly dismantled.

Porky’s trepidation certainly isn’t without reason. A shot from his point of view places the audience in his hooves shoes, thereby justifying his forthcoming anxiousness. Not that it wouldn’t be justified, but Jones seemed to understand that this sudden onslaught of anxiety for the convenience of plot can sometimes be contrived and too convenient—momentarily encouraging the audience to look through Porky’s eyes helps to bridge that gap and add a layer of sympathy. A successfully dizzying layout is certainly helpful in ensuring all of these factors click; the shot is constructed at a diagonal angle rather than a full on vertical drop to offer a fullness that translates into a tangibility, which, in turn, translates into a greater sense of danger.

Bugs Bunnyisms with the ant continue as he mocks Porky for his plight. Not outright, of course, but the ease in which he slide-gallops to the other ledge, no buckling with the rope in sight, is certainly salt in the wound. Those may recognize this odd “walk cycle” as being reused from Porky’s Ant, which, coincidentally, was one of the short’s bright spots in that short too. Its recycling here isn’t distracting and fits comfortably within the context of the scenario.

Nonchalance of his demeanor offers a buffer against the more open giddiness that ensues as he makes a deliberate attempt to be inciting; if Porky had trouble walking the tightrope before, then he’s certainly run into twice the trouble when the ant begins shaking said rope to knock him off.

Attempts by Porky to stay on are convincingly manic in their animation… at least, manic for the standards of this cartoon. The animators even insert subtle acting details, such as Porky fetching his hat when it falls off. There’s something to be said about his character in that he’d be willing to risk the security of two hands on the rope for ensuring he has his hat and looks like the presentable little authority figure he fancies himself to be. A subliminal preoccupation with aesthetic sense and even just mental security—perhaps to him, Porky Pig is not Porky Pig without his workman’s hat. Even—especially—in life or death situations.

Granted, with over three minutes of runtime remaining, there won’t be much death given that there’s still a conflict and story to abide by. Instead, the ant moves along with his galivanting. While it’s encouraging to see that the ant isn’t actually a twisted masochist out for Porky’s blood and is only attempting to get his kicks in, the suddenness in which he drops the act is a bit too sudden. That’s moreso on Jones’ part than acting of the actual ant; the shift in music and overall tone is abrupt, but not conducted in a way that communicates said abruptness is a joke in itself.

Nevertheless, a concrete finality is reserved for the end of the act: the ant spinning down the curves of the (much larger) rope and posing for the audience. This, too, lingers a bit longer than necessary, particularly with a rather arbitrary topper involving the ant being thrown by “aftershock” convulsions. Porky’s side of the story hasn’t necessarily gotten a clear resolution, and there’s still a lingering concern on behalf of the audience as to how he’s faring or what he’s thinking. The ant is cute, but not cute nor entertaining enough to warrant such a grandiose highlight that disconnects itself from the story. Ironic, given that the short has been following the acrobat theming for nearly two minutes. There just seems to have been a better solution to ensuring such a tangent reads more purposefully than is actually the case.

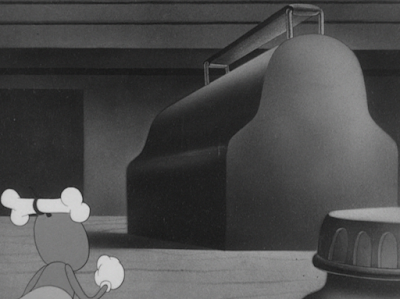

An entirely new tangent is nevertheless inducted as something catches the ant’s eye off-screen: Porky’s food. Another bit of warped scale, the table and its comestible contents looming over ant not only reaffirm his tiny stature, but render the food all the more appetizing through how large it is in comparison.

Enter needless prancing. Jones seemed to hold a particular infatuation with twists and turns and spins in this cartoon, whether it be the ant’s descent down the rope or up the spiral table legs. The novelty has grown a bit tiresome since—however, it succeeds as a comparatively more interesting maneuver of climbing.

Both shots of the ant approaching the sandwich don’t hook up as nicely as they have the potential to; though there is no need to linger on the ant covering every spiral service on the leg, the cut obliged by the camera right as he’s running feels abrupt and sudden. Particularly because the adjacent shot has the ant immediately running into frame, implying he’s just teleported. The general gist of his ascent and intentions are clear, but there could stand to be a bit more balance in the way the sequences are strung together. The random running in place, pausing for no discernible reason, and then rushing to the sandwich don’t offer many additional favors.

And, as it turns out, the attraction of the sandwich is not only its food contents, but its availability for the ant to show off his acrobatics even more. A tangent of the ant jumping up and down on the bread like a giant trampoline unfortunately reads a bit ham-fisted rather than truly necessary—the whole acrobatic theming seems to be drawn along outside its welcome. Maybe that’s the entire intent of the character, given that the bottom of his cage brands him as a trained ant. Nevertheless, intentional or not, the novelty has begun to falter, and attempts to keep honing it back in aren’t very successful. Commit to the new act of the cartoon.

A smaller, more inconsequential critique: the effects animation as the ant flops into the sandwich is unintentionally disarming. Bread crumbs are certainly not a liquid. That is, unless Porky prefers his sandwiches extra damp.

This again is all nitpicking. As always, Jones manages to express his main ideas clearly: the ant is clearly infatuated with the idea of the sandwich, is going to eat said sandwich, and a confrontation will surely ensue. Chuck Jones’ continues attention to detail is as admirable as it can be sometimes frustrating. That he’s making these considerations at all, milking these little moments for all they’ve got, is certainly telling about his commitment to an idea and a cartoon. However, sometimes the axiom of Keep It Simple, Stupid is the most choice advice a filmmaker could take. If Jones were to really lean into these little extravagances and make their integration in the cartoon feel purposeful, that would be another story—for now, the ideas are lodged in a bit of a purgatory.

With all of that out of the way, the ant happily indulges himself in a dry, crumbling, decidedly un-liquid piece of bread.

The camera engages in a jump cut that is made particularly jarring through the drastic change in scale; where the ant was once smaller than the height of one slice of bread, he now finds himself as tall as the entire sandwich. Such is a symptom of clarity—if the ant remained the same height as the bread slice, then he would appear positively microscopic when the camera pans out to reveal Porky. Likewise, if he was the same height as he is now with the sandwich enlarged, then viewers would be encouraged to mull over Porky’s supernaturally large sandwich. A bit of thinking and planning got lost in the sake of a gag, but that isn’t always a negative. It can even be a necessity. For what Jones is attempting to accomplish, however, the oversight does become a bit of a distraction, even momentarily.

Porky, thankfully, suffers fewer issues. In fact, he excels—the shading on his features and forms again establishes him as a real, palpable threat. A threat that moves and breathes and eats sandwiches and struggles to walk tightropes. Porky isn’t intended to be the antagonist of the short, of course—one most remember that the ant is heckling him—but he does fill a necessary niche as offering a threat or impending narrative when the story calls for it. Sympathy is split between both characters throughout the short. In this instance, viewers are more endeared by the ant’s mischievous boundary breaking and indulgences. Thus, Porky is painted to seem like a bigger threat who has come to stop his fun.

Jones’ no-nonsense reveal of Porky is great at communicating this paradoxical stolidity; having him seem to suddenly appear makes any impending conflict all the more interesting than if we were treated to a laborious scene of him climbing down the tightrope and looking for the ant. (Even if this is antithetical to earlier critiques regarding the lack of clarity with Porky’s whereabouts.)

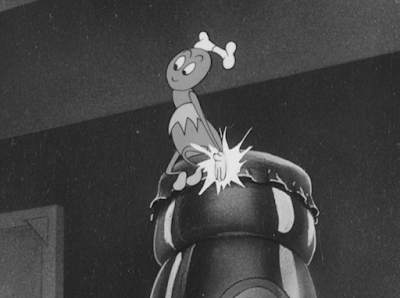

Heralding Porky’s arrival furthermore heralds a minute of gags surrounding Porky, the ant, and his meal. That is, the ant finding various ways to weaponize said meal against Porky for his own viewing pleasure. Smacking his sandwich and revealing a giant hand-print shaped hole, thus removing the sandwich’s edibility (ignoring that half a sandwich doesn’t disappear when you smack it) is a relatively tame example—having Porky get his hand stuck in a jar of mustard, aggressively beat it off the table and hurt himself with the same ferocity is a bit more duplicitous.

Unsurprisingly, this charade lasts much longer than it needs to, but doesn’t feel nearly as insufferable or contrived as it has the overwhelming possibility to. Having Porky get his hand stuck in a jar and struggle to get it out certainly feels like the plot of an early Chuck Jones effort, comparable again to Disney’s Pluto getting stuck to flypaper and all of the contrivances therein. However, having the ant “talk” him through the process certainly offers further comedic layers that render the charade less obligatory and perhaps even understandable.

Realizing the ant is hiding in the mustard, Porky is quick with his impulses to jam his entire hand in the jar. Ant chides him from a nearby bottle of soda… just as he offers advice, encouraging Porky to smack the bottle off of his hand with the table. This comparatively “congenial” attitude from the ant and encouraging his constant egging of Porky—the camera repeatedly cuts between Porky fiddling with the jar and observing to the ant’s pantomimed advice to the ant building off of said “advice”, convincing him to hit harder and harder—allows the audience to take interest in the actual filmmaking than the issue itself. Following back and forth parallels between the ant and Porky, with Porky doing as the ant says, looking over to ant, ant telling him to do something else, rinse and repeat develops a hearty rhythm that inadvertently draws the audience in.

Rhythm or no rhythm, the charade does extend its welcome, but is at least more understandable as to why it goes on so long. Such a routine can’t be rushed for the sake of Jones’ intentions. To rush it would undermine the actual “punchline”, if one would call it—the jar breaking as Porky slams it into the table and the loud, echoing “OUCH!!!” that ensues. His outburst is especially effective given that his scream is the first formal line of dialogue uttered in four minutes. Ditto with the slow burning exposition.

The ensuing close up of Porky nursing his mustard-logged hand is a bit awkward regarding the general flow of shots (as well as clarity; are the tears coming out of his eyes a delayed reaction to the pain or the spice of the mustard, if it is spicy to even begin with? Would either situation really demand his eyes to be that bloodshot?), but, if nothing else, certainly is memorable. He isn’t nearly as appealingly drawn as he is in the scenes leading up to this, but, again, given by the giant scowl on his face and the almost arbitrarily bloodshot eyes, cuteness doesn’t necessarily seem to be the main idea.

This too is another scene that is excessive in its tactility, owed to the various shadows and highlights on all environments. Perhaps such tangibility makes the close-up disarming just the same, but it certainly is memorable and even admirable. It may not be incredibly harmonious with the rest of the sequence, but it sure is mesmerizing.

Ever so saintly, the ant sacrifices the bottle he was sitting on for Porky’s convenience of consumption, whether to wash the taste of mustard out of his mouth or eliminate any loosely implied spice components of said mustard. Overzealousness in which Porky ingests the liquid suggests the latter, but it does feel as though there would be more setup to illustrate that this mustard is indeed hot. Ambiguities of this conflict aren’t exactly helpful to the coherency of the short.

.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment