Release Date: November 8th, 1941

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Chuck Jones

Story: Chuck Jones

Animation: Phil DeLara

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Dispatcher, Rider)

(You may view the cartoon--albeit unrestored--here!)

Saddle Silly colloquially marks a transitionary period to a transitionary period for Chuck Jones. All of the cartoons directed by Jones’ unit from here to Conrad the Sailor, released at the tail end of February 1942, are without a writer’s credit—thus implies that he wrote this slew of cartoons himself. It certainly would coincide with The Brave Little Bat heralding the last Warner credit for Rich Hogan, despite not formally moving to his next gig at the MGM studio in mid 1942.

Jones’ presumed writing of his own cartoons isn’t entirely what constitutes this transitionary period, but, rather, the shift in tone. Saddle Silly is notably more free-spirited, loose, and perhaps obvious in its attempts to follow the comedic mold so erected by the studio. Not to imply that all of the shorts leading up to this one haven’t been funny—quite the contrary—but Jones’ pursuit for humor and abrasiveness is at some of its most tangible up to this point.

This is immediately apparent through the opening alone: a phony foreword indebting itself to the Pony Express Company for its lack of involvement. Such disingenuous sentiments kickstarting the cartoon were rife throughout the ‘30s (and a few exceptions in the ‘40s), but weren’t relied upon as they once were. Perhaps this utilization of such an informal throwback inadvertently dates the cartoon and its attempts at humor, when, ironically, attempting to do the opposite. Nevertheless, opening with such a disclaimer immediately clarifies Jones’ intention. No Sniffles or Curious Puppies short opened with these same tidings—there is a deliberate strife for comedy and strife for change here.

Even with all of this in mind, one would be hard pressed to take the auteur out of Chuck Jones; the short’s opening 30 seconds consist entirely of a long, sprawling camera pan, observing as a pony express rider careens up and down the various canyons—sometimes to a degree of proud improbability. Carl Stalling’s screwball, playful, somewhat off-key orchestrations of “Light Cavalry Overture” erase any room for doubt that this opening is full of merriment and silly hijinks; it is a bit (or a lot) forceful in its attempt to push a lighthearted atmosphere, and doubly so when analyzing the animation without any sound, but remains relatively harmless.

Overlays of various rocks and canyons are intermittently injected into the foreground, ensuring these backgrounds have dimension to them and aren’t just a side scrolling cartoon backdrop. They serve as a nice addition, but could stand to be a bit more purposeful in their inclusion. One single foreground element every ten seconds or so doesn’t do much to tighten the composition or give a purpose to said overlays. Instead, it reads exactly as it is: somewhat haphazardly placed objects to reassure the viewer of the environments’ depth, rather than the environments actually feeling lived in.

That is moreso reflected in the actual animation through subtle staging maneuvers: when climbing the façade of the canyon, the rider momentarily stretches off screen as he reaches the top, with the top obscured by the camera. Resisting the temptation to pan upwards and follow this new elevation renders the short less “subservient”—the backgrounds don’t bend to the every whim and desire of the directing. These touches inject a naturalism that is rather important—in any context, but especially beholden to such a long and potentially monotonous sequence that relies on these “subversions” to maintain interest.

Our trek comes to an end as the camera settles on the object of the rider’s pursuits: the p(h)ony express station. Those pondering about the specificities of “HE-2878” would be correct to ponder, as that was the phone number of former Warner background artist Elmer Plummer. He’d been absent from the studio for a little over three years at this point, where he’d place his stakes at Disney and be one of the few to remain after the infamous 1941 strike. A special irony, given that he was heavily active in the Screen Cartoonists Guild… just as Chuck Jones was. His shoutout here is likely a playful bit of union solidarity.

Thus, we formally invade the privacy of the pony express office and receive an intimate inside look at their daily chores. Stalling’s relaxed yet decidedly cornpone accompaniment of “Oh, Susanna!” supports the humble atmosphere reflected in the backgrounds and animated activity—writing a letter to be sent out by the riders certainly doesn’t share the same wacky hijinks as riding up the side of a cliff.

Instead, it offers its own unique avenue of humor. A close-up of the man’s hands as he fills his quill like a fountain pen is as intentional in its uncanniness as it is habitual: the sheer juxtaposition of such chiseled, detailed hands and the subversive, impossible nature of the gag is strong and purposeful, but such an intimate close-up feels indulgent all the same. Completely divorced of context, this shot could easily be found in a short like Old Glory or Tom Thumb in Trouble. Not only due to the eerily realistic human hands, which is of course a giveaway, but the overwhelming care and gentility in the animation.

Gentleness in the atmosphere is nevertheless intended beyond artistic self indulgences. That way, the radio transmission interrupting our nameless author’s writings is made more intrusive.

Sure enough, the camera cuts to a more intimate view of our pony express rider, official purveyor of gags. Rather than cutting to blue skies and vast canyons, the camera reveals the rider to be lost in a dense thicket of fog—a stark tonal contrast to the blue skies and vacancy found in both the canyons and the pony express office. The opening pan does depict this same fog, but with a degree of flippancy that doesn’t rouse excessive suspicion from the audience. In other words: this sudden cut to dark skies and thick fog is jarring, successfully antithetical to the cozy atmosphere so laboriously constructed up to this point, but not to the point where it’s completely discombobulated or divorced of all clarity.

The rider’s commentary to ”Barancha” adopts that of an airline pilot’s, reporting on the ceiling and visibility. Even this gag is a bit pedestrian for the time in which it was released, but is rescued through the insertion of a decidedly corny topper. Maintaining that same monotone drawl, his reporting of “Where the heck am I,” is much more akin to a statement than a question. Blanc’s unwavering delivery is what makes it work. Said delivery following the ever popular rule of three’s certainly doesn’t diminish its rhythm or successful impact, either.

Despite the fog lifting, the same routine persists—now thanks to the rider’s hat pulled over his eyes. The routine has grown a bit stale by this point, and doesn’t exactly warrant the additional runtime. A hat lodged over someone’s eyes isn’t an earth-shattering revelation. Still, Jones somewhat compensates comedically through the rider’s monotone utterance of “Wish you were here,” after a notable pause.

“Calling 44… calling 44… pull your hat over your eyes, you big jerk.”

This utterance on the other side of the receiver garners the biggest laugh. Sustaining that same, almost obligatory monotone voice offers a nice parallel to the rider’s own stolid drawling—that, and such an acerbic insult delivered so casually reaps its own benefits through juxtaposition. Nonchalance in which he offers those orders indicates that this is a relatively common recurrence. Thus, the gag is made all the richer.

A signature Jones-ian indulgence sneaks its way in as the camera finally dissolves: the sly, self aware grin of humility. It’s a bit unnecessary (as most of these “concessions” tend to be) but relatively harmless.

Plane allusions are maintained through “44” claiming he’s coming in for a landing—thus, Jones mixes his metaphors by casting the horses as a bunch of benchwarmers waiting for their big chance. All of the horses are inked different colors to give a believable variety; likewise, the whole pony express operation just feels bigger that way. It’s a nice consideration of detail, especially given that the standard “Chuck Jones Horse” is almost always the same design and color.

So, acting as though he’s been summoned to fraternize with his coach (which he has), our star horse traipses over to receive instructions. Animation of his jog skews on the slower side, accidentally injecting an arbitrary floatiness that renders the final product a bit awkward, but this in itself is a bit of a sacrifice: the whole point of the run is to accentuate how human and un-horselike it is.

No discernible dialogue is shed amidst their conversing, but it doesn’t need to. Without a coherent word spoken, the sports metaphor is communicated just as clearly—Stalling’s continuously peppy, brazen, marching band-esque accompaniments play a considerable role in ensuring the security of the metaphor.

This metaphor falls into the same vice as many of the gags leading up to it: persisting past its expiration date and deflating the longer it goes in. It isn’t awful, and Jones’ commitment to such theatrics is certainly to be commended. A 15 second sequence dedicated to the horse stretching does steer on the unnecessary side; for a sequence making such an attempt to establish itself as spry and sporty, neither of the two adjectives are aided by the bloated pacing.

Likewise, the horse getting into a running position only amounts to more running. A logical conclusion, obviously, but the lack of differentiation in tone and pacing continues to drag the metaphor through the mud. There is no tangible shift in demeanor. He runs at the same pace as he walks, the same pace as he stretches, the same pace as he teetered over to his “coach”. Indulging in such lugubrious preparations begs for a sharp antithesis with the actualization of the results: have the horse take off in a blur of dry brush. Change the music. Enact a change of some kind that makes it feel as though there is actually an objective being accomplished.

All of this preparation amounts only to more preparation. Which, thankfully, is much more purposeful and intentional in its careful pacing: the horse galloping in place with his “hand” behind his back reveals the completion of yet another metaphor: the pony express rider serving as a human baton in a twisted, anthropomorphic equine relay race. Again, one has difficulty shaking the sense that the sequence wouldn’t be more successful if there had been a tangible shifting in tone and pacing amidst the preparations. Having the horse race to his receiving position in a blur, only to soften into his galloping in place at the drop of a dime would allow the absurdity of the baton relay gag to thrive all the more with such notable changes.

The mere visual of the rider being passed with such unquestioning nonchalance nevertheless makes it all worth it. To build up a genuine sense of momentum, the camera begins to inch forward ever so slightly on one of the shots following the horse’s self-maintained galloping. A greater anticipation builds through this crawling climax, strung together by the shots of both horses alternating in quickening succession. Thus, when the passing finally does take place, a real sense of accomplishment is garnered by viewing both horses (and human) together in the same shot. An earned climax and resolution that rewards the audience for their patience and viewing these parts come together—horse galloping in place, other horse galloping with rider, back to the first horse, back to the second, first horse grows more momentum, second growing closer, etc, etc.

Ready to prove himself as a director capable of a sense of humor, this new development of the rider receiving another steed heralds its own slew of gags. One being a gang of horses inside the station viewing as the rider goes past, turning their heads in perfect synchronization (and the accompanying wind whistling through their names to accentuate the rate of speed exhibited by the rider.) This in itself is a callback to a gag that can be found in dozens of the mid-‘30s Warner shorts; it’s nothing new, but is nevertheless cleverly synchronized and clear in its intent. The latter being a particularly important priority, given that so much information is communicated off screen through sound effects. It’s a gag of implications.

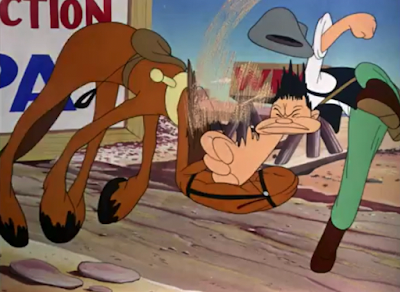

Our next means of hilarity spawned by this rider-horse duo: the two soaring past a modest little hitchhiker who is both proudly incongruent with the reigning character designs and tone of the short, and completely in line with Jones’ design—and humor—sensibilities.

The Chuck Jones “Little Man” is essentially a continuation of Tex Avery’s prototypal Elmer Fudd—particularly the one touted in Little Red Walking Hood. That is, a stout, funny looking guy who deliberately interrupts the flow of the cartoon. The Dover Boys boasts this same archetype with the galloping old sailor man: a much different design than the man here (who is more comparable to the recurring customer in Porky’s Café), but both promulgators of the same values. Note that one of the items caught amongst the breeze appears to be a toy dog for added security of nonsense.

Gags still continue, but are now focused back on the horse and his rider to give the short some semblance of a story. Even if said story semblance is the two of them running over a cliff and falling into a body of water. Not particularly thrilling or funny, but, as is the theme with this short, a refreshing change of pace and direction. The camera taking a moment to pan back and forth, as though hastily hunting for its subjects, is a nice observation of the same technique seen in many of the other shorts by Jones’ contemporaries. That said, it isn’t so much a feeling of looking back and forth as it is the camera panning outward, halting upon realization that there is nobody to follow, and sliding back to the edge of the cliff…

…and back down. Technique in the background paintings for this short lack the tightness and confidence of Julian’s other paintings for Jones up to this point—in our dissection of The Brave Little Bat, I noted the change in background styles and attributed it to Paul Julian moving his stakes to Friz Freleng’s moment. I seek to rectify my claims a bit: it seems that he actually dipped out of Warner cartoons entirely, taking up a brief stint under the Works Progress Administration and focusing his painting talents there. Most notably his 1942 mural, Orange Pickers, currently residing in the Fullerton Post Office. He would return to Warner’s shortly thereafter, permanently adopted into Freleng’s unit (save for some freelance work at UPA throughout the ‘40s, which would house his talents after he completed his stint at Warner’s in the early 1950’s.)

As mentioned before, the lack of background and layout credits until the mid ‘40s certainly cause more headaches than prevent them. This very well could be Julian’s background work—it very well could not. My own perception skews to the latter, in that the environments feel much too blobby, vague, less conscious of the lighting and sharpness than touted in his shorts thus far. There is a clear difference between the technique in Saddle Silly than in The Brave Little Bat.

Nevertheless, all of this bloviating is to commend the backgrounds here on their wide array of color. Browns, oranges, and earthy blues have largely dominated the color scheme thus far; vibrant purples and maroons and reds of the canyon as the camera scales down certainly adds an appropriate grandeur to the cavern that, in a way, accents the greatness of the rider’s fall. This isn’t an insignificant puddle he’s landed in.

Clearly discontented with his situation, the rider mouths some choice words. Choice words that amount to bubbles—that the camera cuts to a shot of the water’s surface indicates that these words aren’t too choice for the bounds of the censors.

No. Instead, they’re much better: Mel Blanc’s ear-splitting “GIDDYAP!” that rings amongst the popping of the bubbles would be funny in any context. Here, with the reigning silence and even docility regarding the bubbles, the whiplash in tone is severe and successful.A fade to black demonstrates a shed of self awareness to the gag’s humor. Better to end on a funny, strong note than attempt to drag it out any further. Some things just can’t be one-upped, and this sense of finality is another strong device often used by the Warner crew and their contemporaries. After all, blackout gag shorts—of which Chuck Jones was some of the very best at—were popular for a reason.

Of course, the effect of the finality only works so much if the fade-in from black ushers a reprise of the gag. Another symptom of Jones’ continued overindulgence. In fairness, the punchline of this gag proves amusing: the bubbles that emit after the fall—and a long, laborious pause, indicating a potential drowning as they gradually trickle into submission—carry the sound of a ferocious splashing sound instead. The main issue is that this feeds into a larger problem effecting the overall pacing of the cartoon; the audience can only take so much starting and stopping and reprising and starring and stopping and reprising for so long. The short doesn’t feel as if it’s made any sort of significant progress, and any progress that is erected is immediately dismantled by the same routine being repeated and driven into the ground.

Nevertheless, this next blackout carries a stronger sense of finality: the rider lugging his waterlogged horse out of the water doesn’t seem to carry much potential for further bubble gags.

Instead, Jones slathers a sheen of sophistication atop a relatively standard, old gag: a horse being a stand-in for a jalopy. A continuing theme, the preparation is a larger takeaway than the actual metaphor of a horse as a gag. Both the motion of the horse stalling out and the rider’s violent vibrations atop the “engine” are captured succinctly—the tactility in the animation really gives the gag an independence and ability to thrive outside of obligation. Stalling’s music score quieting in favor of Treg Brown’s huffing engine sound effects contribute the same effect.

More reprisals of old themes to steer the short back on track: the same rollicking accompaniment of “Light Cavalry Overture”, complete in its whimsical tilt with the melody, and the same “little man” asking for a lift.

He, too, is met with the same answer. A gust of wind in place of a resounding no. The addition of the sign hints towards the audience that this little fellow will build to a climax—it’s a certification that we will be seeing him again, and each time we do, there will be an addition of comedic grandeur.

Reprisals extend to retreading extended gags too—once more, the momentum of the cartoon falters in favor of another “cliff gag”. Jones attempts to insert a twist by having the horse skid to a stop, leaving the rider airborne, but the format is still synonymous to warrant polite exhaustion at such tedium.

Even so, the animation of the rider is serviceable. Comedic priorities shift from his oblivious sailing over the canyon to the imparting of his habits, slapping his invisible horse and still moving as though the equine is bucking beneath him. It’s really the lack of momentum that deflates it; the actions confined to the gag itself are fine. Tedium of this gag is a reaction to the tedium of other gags, which, in turn, is a reaction to those other gags.

Invisible bucking act continues upon the inevitable realization of the lack in gravity. As long as this gag goes in, the actual details are salvageable enough to entertain. Perhaps an additional novelty stems from seeing a character in a Chuck Jones cartoon looming over a cliff and remain in the air, even after sparing the Glance of Doom that so often seals the fate of many a Coyote.

With the rider secure on the horse’s back, the audience is left to ponder what direction Jones will take the cartoon in next. Surely we have exhausted all means of repetition.

Surely not. Again, the additional building of absurdity rescues the joke from too much exhaustion. Juxtaposition between the billboard and the lonely desert surroundings is stark, as is the whiplash between the steadied, adventurous tone surrounding the horse and his rider and the juvenile capriciousness with the little man.

Nevertheless, the short is breaking five minutes at this point with nothing of any real substance occurring. This in itself wouldn’t be as much of an issue if the short didn’t attempt to frame itself as something more; Jones struggles to give this short an identity, constantly toeing an ambiguous limbo between spot gag and story driven. A vague, transparent purgatory of confusion ensues.

Some semblance of self awareness seems to slip its way through regarding this issue. A fade out and back in finds the camera in an entirely new location: “Indian Territory”, as so helpfully indicated by the giant sign and all its punny parodies of the song “Loch Lomond”.

This predictably spurs the conflict of the cartoon, only five minutes in. And a conflict easy to guess: An Indigenous man (of course named Moe Hican, as indicated through the anachronistic mailbox in front of his tipi) is the obligatory enemy of our rider. The short doesn’t even slip into usual stereotypical motives (such as Moe wanting to scalp the rider)—he just chases after him because he can, and all Native Americans in golden age cartoons are immediately antagonists, because of course.

Pacing of his introduction does stagger a bit, victim to many of the pratfalls exacerbated prior. The camera indulging in a diagonal pan to him keeping watch over the canyon, eyeing the rider back on his trek is serviceable—it clearly establishes that he has his eye on the prize and plans to run chase him. Stalling’s music is tense and moody to communicate this little pipsqueak as a threat. All that is fine and dandy, but there do rise a few hiccups when Jones obligates himself to more gags: a cut of Moe rushing into his revolving door tipi dissolves to him already sitting at his decidedly dainty vanity.

These two ideas are fine on their own. The contrast between the furnishings on the inside and age old stereotypes of Natives being primitive and archaic is enough to meet Jones’ 1941 standards for humor. Ditto with the revolving door attached to the tipi—“modern” appliance against “modest” tipi. Nevertheless, both gags don’t hook up together very well. They communicate exactly as they are: obligations to meet a joke hastily strung together.

Perhaps that deduction is, yet again, partially aimed at another factor that inadvertently blends into the other two. The camera cuts to the powder on Moe’s vanity: a double-pun with Wild “Buffalo Bill” Cody and the beauty brand Coty. Cheesiness aside, the wordplay itself is harmless—it’s all in the momentum that is heralding the most issues. A gradual camera truck in to the powder is unnecessary; its arbitrariness is further exaggerated with such uneven pacing and directorial focus.

Jones indulges in a jump cut from the powder to Moe Hican rushing out of the tipi, further skewing what little pacing is present. Such is nevertheless a cross to bear, as more important priorities persist: priorities such as Moe using a ladder to scale his horse and chase after the pony express rider.

Kudos to Jones’ design sense and the horse. It’s simple, but works in more ways than one. The stocky, heavy build is a shark antithesis to Moe’s diminutive stature, already successfully concocting a comedic dissonance. However, the density of the horse is likewise as much of a parallel to the pony express rider’s own horse, who is much more puny in comparison. As hilarious as the visual is between Moe and his oversized horse, said horse casts a substantial threat all the same. Or, if not a threat, a discernible hierarchy in power.

Speaking of Paul Julian and the Works Progress Administration, this short is further dated through its New Deal-isms with a WPA project serving equal time between its status as a gag and an obstacle. Rather troublesome when locked in a pursuit.

So, rather than attempting to rush around it or find a detour, the rider utilizes his horse as a sacrificial shield as he prepares to take aim.

That is, if the horse is willing.

Predictably, the gag runs long. It is clever—a neat way to anthropomorphized the horse outside of usual stock tropes and decisions, and an anthropomorphism that is completely logical. If horses could talk, could have human consciousness, they very likely would object to this treatment. However, the novelty is worn quickly through the laboriousness of the pacing. It is worth noting that Art Davis did this same gag 7 years later in Nothing but the Tooth, which was paced much more quickly; perhaps that is where the complaints of pacing stem from.

That, and the fact that Moe doesn’t serve any significant threat. He pursues the rider, of course, but hasn’t displayed any sort of violent tendencies. His only justification for being a threat is purely due to obligation. In Hollywood films and cartoons alike, the Natives are always the bad guy. Even—especially—if they haven’t done anything to make themselves the bad guy. The arrow slinging, war-crying stereotypes these shorts are so filled with isn’t a much better alternative, but it would at least justify such a moment as this one here. There is no real reason for the rider to stop and shoot if he’s not being shot at first. Largely unfulfilling and anticlimactic, if not completely perplexing.

Our rider slash horse shield enforcer gets his wish through blunt force trauma: as long and taxing as the entire charade is, the acerbic sting of him punching the horse into the ground and nullifying him is certainly a strong, effective contrast against the lugubrious, if not domestic pacing.

Unconsciousness of the horse is a staging necessity too: how else would the parallel of the rider and Moe staring each other in the face be presented? Jones does score additional points for the surprise aspect of Moe’s appearance. It’s a given that the two would cross paths, but this short is a bit reliant on spelling certain gags and motives out—the restraint necessary to make this gag work is a refreshing development.

Even if it is incredibly short lived. In short time, both riders are reacquainted with their horses—the fruitlessness of the entire climax is thusly harped on. While it is implied the rider is trespassing on Native land (moreso than usual, anyway), the lack of weapons on behalf of Moe is genuinely puzzling. Not to play into the stereotype that all Native Americans are ruthless savages as these shorts so love to imply, but if Jones was to use such a role as his antagonist, then it would be helpful to lean into that to begin with. Shorts such as Nothing but the Tooth or A Feather in His Hare, both starring dweebish adversaries, make an attempt to have both antagonists fulfill their roles. Even if both shorts serve to demonstrate just how low their rate of success is as said adversary.

All it takes to incapacitate Saddle Silly’s Moe Hican is for the pony express rider to barricade himself in the fort to who he is delivering. Outside of Moe’s horse skidding to a rapid halt, burying itself in the ground and prompting a somewhat unnecessary close-up of a dazed Moe Hican, we never see him again in the cartoon’s runtime. An incredibly obligatory climax that doesn’t even become a fully fledged confrontation.

Jones’ directorial priorities lie elsewhere. Particularly, demonstrating that the rider has made it safely and is ready to drop off his parcel. Designs of the guards and overall prestige surrounding the fort create a nice antithesis to the humbleness of the rider and his surroundings—even if this introduction of said fort feels completely random.

There is a backstory implied through such details, which is nice. However, these details are so explicit and calculated that it seems to beg further explanation that was never given. Why is he delivering on Native territory? Who is this prestigious, mustachio’d general? Why and how is there a headquarters? Suspension of disbelief is a necessity when confronting these cartoons, but sometimes, the cartoons seem to set themselves up for such questions. The confusion regarding the context isn’t the same sort of confusion that applies to wondering why a character plummets to the ground only after he’s made eye contact with the ground.

The most important priority is to nevertheless establish the safe return of the Little Man, emerging without question from the rider’s tote, sign in hand. This too is a non-sequitur, but probably the most rewarding out of the who’s cartoon. It goes to show that following in Ted Avery’s footsteps often leads to success—no matter how distilled.

Saddle Silly, to deem it colloquially, is a “nevertheless” cartoon. A short that is riddled with multiple inconsistencies and fallacies, multiple incoherencies and multiple missteps that are best shrugged off and moved away from. Because, the fact of the matter is: this short isn’t really remarkable enough to genuinely get mad at.

Most shorts, I find that if I dislike it upon my first viewing, my opinions warm and soften as I actually carve into the interworkings and language of the cartoon. Give it a chance, listen to what the filmmakers were attempting to achieve, how they did or how they didn’t. This was a rare case of the opposite; I certainly don’t actively dislike it, but found myself noticing many more holes and incoherencies and unhelpful patterns that turned the cartoon into a bit of a slog.

Part of that comes by design. As has been mentioned in multiple reviews, the myth that Chuck Jones’ shorts were never funny before 1942 is dead wrong. They were funny, often more than most realize—it just depends on what that funny is. What may have been funny to Chuck Jones in 1941 is not funny to us. What he may have intended to be funny differs from what we find funny. Even the shorts most populated with his rampant Disney influence aren’t the completely droll, unfunny pieces of nothing that so many make them out to be. Even Old Glory, perhaps most lambasted by modern critics, intends for audiences to laugh and titter politely at Porky’s disregard for the pledge of allegiance. Ditto with Tom Thumb in Trouble, which boasts visuals such as Tom cleaning the ears of a human shaped pot. Neither of these are exceedingly funny—especially not 83-84 years later—but they are attempts to lighten the mood and at least crack a smile.

However, an actual, consistent, nonstop pursuit of comedy was still a rather new concept to Chuck Jones. This cartoon was clearly made in the mold of his contemporaries, attempting to mimic certain gags and impulses that have garnered laughs at other showings. There is a very clear attempt to deviate from his comfort zone, and that is where those errors become most prevalent. Of course this short isn’t going to be as polished as something made in the mold of Sniffles or The Curious Puppies.

The Draft Horse is usually seen as his first true breakaway, the floodgates that opened to shorts such as The Dover Boys and My Favorite Duck in the same year. Perhaps Saddle Silly is the lock to the floodgates of The Draft Horse. Draft Horse follows a similar pursuit of comedy and mimicry of the other directors’ styles—the successes of that short may not have been as apparent if he didn’t first get his feet wet with this one.

It is likewise important to remember the historical context of this short. It’s too easy to compare to the successes of The Draft Horse or The Dover Boys, but there was no Draft Horse or Dover Boys in November 1941. These gags we find so tame (sometimes at best) weren’t nearly as droll back in the day. Likewise, it is still fair to argue that the gags just aren’t funny—it is an arguable truth that the other directors were making cartoons that garnered more laughs, even at that time.

It’s not one of Jones’ most coherent nor clean cartoons, but it isn’t a complete waste. Despite so many gags failing to communicate (or being drug through the mud with needless repeats), there is a genuine sense of commitment behind them. It doesn’t necessarily feel like Jones squeaking another cartoon out to meet a quota rather than an unfortunately misguided attempt. There’s a certain respect to be had for that just the same. It doesn’t hit the mark all the way, but that this short exists at all is indicative of the growth and restructuring in Jones’ unit. There is a sincere desire to branch out and get on the same standing as his colleagues. In due time, he’ll be towering above them.

No comments:

Post a Comment