Release Date: September 27th, 1941

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Chuck Jones

Story: Rich Hogan

Animation: Rudy Larriva

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Margaret Hill-Talbot (Sniffles), Marjorie Tarlton (Batty)

(You may view the cartoon here or on HBO Max!)

As mentioned in our prior dissection of Notes to You, the start of a new theatrical season always heralds thoughts of change and progression. What the year holds ahead. What came before it. Some shorts are, of course, more indicative of this new change than others; just because a short is the first of the new production season doesn’t really mean much for the content of the short.

All This and Rabbit Stew officially heralded the start of the ‘41-‘42 production season, but The Brave Little Bat is a cartoon made at the top of the season that is indicative of the forthcoming changes.

Such as the last short to be written by Rich Hogan. Given Hogan’s close and frequent collaboration with Chuck Jones over the past handful of years, he’s as much responsible for indulging in and furthering those sensibilities so rife for comparison to Disney than Jones was himself. Jones’ unit didn’t collapse with him gone, but it certainly plays a big part in Jones’ moving away from that sort of directorial saccharinity. Bedtime for Sniffles, Good Night Elmer, Old Glory, and a laundry list of others bear his collaboration, painting a relatively indicative tone of his contributions for Chuck Jones.

That isn’t to deem him as a writer only cast in Disney’s shadow, of course; Hogan shoulders the noble responsibility of writing one of the most notable cartoons of all time: A Wild Hare. His departure from Jones’ unit comes from him following Tex Avery over to MGM and serving as one of his chief writers for over a decade—he certainly had the versatility, and often had a hand in writing the very shorts that poked fun at the sort of image he helped craft during his time in Jones’ unit. (Garden Gopher, for example, stars a particularly cutesy, cloying gopher.)

Hogan wasn’t the only person marking a departure with this cartoon. This is, likewise, the final cartoon to bear the vocal talents of Margaret-Hill Talbot. Talbot assumed the role as the studio’s representative of cute, gently saccharine voices, serving as an informal successor to squeaky voiced Berneice Hansell. Across the board, cartoons have gotten faster, more abrasive, and generally less reliant on the warm or purposefully cloying vocals that was so dominant throughout the ‘30s. Even with this in mind, Chuck Jones partially kept that spirit alive through his repeated casting of Talbot as Sniffles. An informal time capsule of sorts.

Perhaps surprisingly, antithetical to how these stories usually go, Talbot’s departure wasn’t a response to structural change within the studio. Rather, an initiator of change itself: it would be here where she would retire from voice acting completely to settle down and have a family.

With that, this is the final “saccharine Sniffles” short to date. 1942 would be the first year not to feature a Sniffles short of any kind, only to be followed the next year with a revamp of the character that would remain until his final bow in 1946. Given that Sniffles was still Jones’ star character at this point, such a development proves rather poignant.

Out of all cartoons that could be made to bid farewell to Talbot’s Sniffles, The Brave Little Bat is a great candidate. The eponymous bat starring alongside Sniffles is voiced by the woman who would become Sniffles’ successor in 1943: enter Marjorie Tarlton. Tarlton’s vocals can first be heard in Sniffles Bells the Cat as Sniffles’ brothers (and you can read a little bit more about her background in the accompanying analysis linked here), but her involvement here is a bit more telling, given that the very role—the voice, the mannerisms, the overall demeanor—she plays here would soon be adopted by Sniffles himself in Jones’ revamp of the character.

Here, Sniffles stares into a mirror at his revamp-to-be. Seeking shelter from a storm in an old, abandoned windmill, he encounters a new friend—that ever amiable chatterbox, Batty—who is soon turned hero when a hungry cat comes into the picture.

As is the case with so many of Chuck Jones shorts to this point, the name of the game is ambience, in which this short bears plenty of. Paul Julian’s background work pulls much of the weight in concocting this simultaneously tense and cozy atmosphere. Cozy through the muted oranges and browns, values dark and low to convey a snug sensation of the sunset. Tense through the dark clouds dotting the sky, accompanied by a particularly foreboding sting of “In A Little Dutch Kindergarten”; such hints that this warm evening bucolicism won’t always be the standard.

Stalling’s choice of music isn’t completely random, either—its foreboding tones served as both an introduction and an antithesis to Sniffles’ cheery, affectionately juvenile music stylings of the same song. Given how tense and foreboding the atmosphere is, its an immediate refutation through Sniffles’ presence (who is decidedly not tense and not foreboding) encourages an incredibly effective parallel. The omen of bad weather or any sort of mishap that could happen to someone as small as him in such a wide, open, vulnerable area won’t get him down. Particularly because he doesn’t even seem to be aware of anything that might require his apprehension.

Jones embraces this incongruity between warm and dark by initiating Sniffles off screen. The camera remains fixated on the same shot of the ground while his singing stylings can be heard—but not seen—on top of it. Such forces the audience to confront the deliberateness of such a contrast; if Sniffles were to appear on screen first, then the association of his song would solely be tied to him rather than the idea of the parallel. Jones’ intended tonal contrast is all the more powerful through these surprises.

Again, as is always the case in these Jones efforts, Paul Julian completely nails it yet again. Puddles on the ground cast a bright, warm orange glow to mirror the sunset—an attention to detail few background painters were mimicking. Foreground elements of various reeds, plants and twigs give depth to the surroundings—a palpable sense of scale, too, since reminders of Sniffles’ diminutive stature against his big, vast world are frequent.

Praises for Julian’s world are particularly important here, since it seems to be one of the very last shorts he did for Chuck Jones. Indeed, he had already been settled in Friz Freleng’s unit for the better portion of the year by the time this short was released. He would remain as his designated painter all the way through 1951, before pulling up his stakes and moving over to UPA. Jones’ next short released, Saddle Silly, touts backgrounds that appear a bit less meticulous and controlled, not as sharp in their contrast in values as what is the case with Julian’s. Conversely, Freleng’s next effort of Rookie Revue does bear a sleekness and conscientiousness in lighting that wasn’t always there in his preceding collaborations with Lenard Kessler. The omission of background and layout credits renders it difficult to make such proclamations in full faith, but it nevertheless remains true that Julian’s time in the Jones unit is steadily waning.

In any case, Sniffles contentedly chugs along in his little toy car, gently weaving in and out of the foreground to cement the dimension hinted by the moving foreground overlays. A bit of an awkward pause lingers between the time he’s finished singing and the initiation of the next action—he moves in a way that indicates he’s going to do something, idly rearing his head with an open mouth. Something does happen, but not in a way that suggests he has any control over it. This idle animation subconsciously indicates otherwise. Nevertheless, the audience is realistically too focused on the idea of his car weaving back and forth and soaking in the environments to scrutinize such a detail. It’s very inconsequential in the grand scheme of things.

Especially when the grand scheme of things involves the violent, jarring convulsions of Sniffles’ car. Treg Brown’s sound effects are beautifully married to Jones’ directorial conviction; instead of rendering these convulsions quaint, juvenile, innocently matching the naïveté of his toy car, the sound effects are approached with the same sincerity and ferocity as a real car getting into a wreck. Ear splitting crashes and bangs and booms that don’t feel like they could be encased by such a tiny little car.

Sniffles mirrors that exact sentiment through bemused blinks at the audience. Momentum of the cartoon completely collapsing to favor such a cloying device often has a tendency to flounder disastrously—it can feel forced and manufactured, completely dismantling any well-intentioned sincerity. Interest in the story or motivations of the characters can be put on hold, which, depending on how engaging the story and stakes are, can prove to be a nuisance. Many risks are involved with such a maneuver, almost to a degree of irony. Something intended to be so harmless can cause so much metaphorical harm.

Jones’ indulgence here is a proud exception. He approaches these befuddled blinks with a confident embrace that equates to a certain self awareness; not to a degree of insincerity or belittlement, but a sense of purpose. Sniffles’ blinks are staunchly obedient to the music, reading as a playful directorial obligation rather than the inverse, which is the case for most occasions—the music is directed to shoehorn in some “plink plink” sound effects that halt all momentum. The cloyingness inherent to such a gesture is acknowledged, but embraced to its benefit rather than shunned or ignored. It certainly helps that the drawing of Sniffles gawking at the camera is so charming. Ditto with how abrasive the movement is, reading as a much more frank antithesis to the free-flowing weaves and turns and constant motion touted moments before.

Rather than having the car sputter into ineptitude right then and there, Jones entertains both Sniffles and the audience through more unpredictable histrionics. That is, the car is sent into a tailspin, starting and stopping and racing out of control, crashes and clangs all the while. Its pacing is somewhat a bit unorthodox, perhaps a bit too confusing than what Jones was intending, but this is an unorthodox scenario. Further nonplussed stares are exchanged at the camera as the car settles into inactivity once more. The unpredictability aspect regarding the car’s breakdown is very well handled, all things considered. A bit jumpy, but, again—such is the intent.

A giant coil exploding out of the front of the car enables the audience to piece together what’s happening. Piece by piece, Sniffles’ car collapses into disarray. Each fault is executed independently, reading as a string of individual incidents (rather than the car failing all together, whether in one fell swoop or through layered collisions)—it’s the same sort of frankness that received so much praise regarding Sniffles’ blinks earlier. There’s a playful obtuseness that doesn’t undermine the severity or earnest of the situation, but presents it in a more lighthearted, confident angle. A continued self awareness in the directing.

So much so that Sniffles’ reciprocates such a commentary: his “Somethin’ musta gone wrong with it!” is rooted in innocence, but just as equally grounded in its salience.

Maybe a bit too much, seeing as he spares one of Jones’ recent pet reactions. A cheeky, cloying grin to the camera that supports these notions of awareness, a metaphorical wink-wink nudge-nudge. Its usage here is perhaps just a bit too excessive, given that his bemused blinks touted earlier meet that quota all the same—however, like everything else, its inclusion is ultimately harmless.

Sniffles’ chair being the last betrayal caps off the aforementioned observations of the sequence’s tone and intent. Frankness of the car collapsing was charming, whereas the chair here could stand to break in a manner that seems a bit less motivated. Sniffles is sent into an airbrushed whirlwind, flopping onto the ground and ridding himself of his seat—the completion of disarray is succinctly made, but the action of the chair spinning out of control feels a bit too perfect in its planning to read convincingly. Jones may have felt that having the chair buckle and collapse would be too synonymous to the car’s breakage.

Jones’ reigning intent with the entire sequence of events is clear regardless: there is no sanctuary for Sniffles. Not even from the forces of nature. A dark shadow envelops the animation of a recuperating Sniffles, with the aid of Stalling’s foreboding music sting to bolster its importance. We’ve outgrown the minor leagues of dilapidated toy cars and spinning chairs—greater challenges lie ahead.

A shot of the storm brewing may read quaintly today, but certainly remains much more sophisticated that the numerous “impending thunderstorm” story beats that obligated their way into the Warner shorts preceding this one. Each cloud is animated on a separate layer; they close in on each other at slightly different intervals, whose parallax supports the illusion of depth—rendering the clouds with semi translucent paint moreover gives them a tangibility more flexible than what opaque clouds indicated with cel paint would allow.

Lightning is somewhat contained to the bounds of the screen, with clouds in the foreground creating a frame. Thus, the effects seem more interactive and believable than if that subtle enclosure wasn’t there—it lessens the feeling of a double-exposed sheet of white flashing on and off the screen.

Rain effects receive similar praises. They are treated with a delicacy that the hard opaqueness of regular cel paint doesn’t always enable; the translucent, streaky brush strokes offer a believable differentiation in texture. Its integration into the picture is aided by the white of the lightning, providing a buffer that allows the two actions together. Once the lightning subsided, the rain is steadily falling—thus, the first few drops are implied to have fell during a moment when the screen was washed out.

In all, it’s a very organic orchestration of events that feels deserving of its camera close-up. This isn’t a highlight meant to fill a story beat. Rather, a driving force that is genuine in its mission to motivate the story and conflict along. Sniffles’ forthcoming reactions to the rain are made to be warranted.

Of course, said reactions are on the quaint side—his steady observation of the rain is interrupted only through the desire to seek shelter, using a nearby leaf (another reminder of his diminutiveness and the explorations wrought from such a uniqueness therein) as a hood. Jones injects the most subtle “plinggggg!” sound in the soundtrack before Sniffles does scrounge for the leaf, indicating that these rain drops are indisputably affecting our star mouse and something to be protected from. Not that the plethora of effects animation currently cascading down his body doesn’t suggest that already, but the inclusion of such a sound effect indicates a sense of purpose.

Structuring the camera from Sniffles’ point of view immediately endears him to the viewer by placing them in his shoes. Such a maneuver is particularly effective through the novelty of the leaf-hood framing the camera; in spite of the threat of the storm, Jones and company do a great job of instilling an oxymoronic coziness. Sniffles using a leaf as a hood to seek shelter from the rain, politely scanning his surroundings reads as charming, quaint, innovative rather than desperate and terse.

As is almost always the case in these point of view shots following a character’s line of vision, the camera sweeps right across the screen, past a key detail, halts, and makes a hasty return screen left to said highlight. In this case, a large, abandoned windmill. The perspective is a bit off when taking Sniffles’ small stature into consideration—even at a distance, the mill would tower over him (or, at the very least, he propelled upwards through a higher horizon line, which is the main culprit). However, clarity is a stronger priority in this moment—there’s only so much room Sniffles’ “hood” enables, and introducing the mill at a first glance works best for the directorial momentum established.

All is nevertheless rectified through the adjoining wide shots of Sniffles running into the mill, whose disparity in size is much more palpable. Jones’ attention to detail is so meticulous that even the painted puddles on the ground project Sniffles’ reflection; a great way to ensure the dimension and synergy of his environments, as well as ensure a little visual interest along the way.

Between the meticulous art direction, emphasis and solidity regarding the effects animation of the storm, and integration of an abandoned windmill, it’s safe to surmise that Disney’s The Old Mill served as an inspiration. Critics are quick to lambast the Jones shorts that explicitly take influence from Disney—however, it proves difficult to imagine this short boasting the lush visuals it does and attention to detail if it wasn’t an influence. Not that a cartoon’s quality is measured through the grandiosity of its visuals, of course, but the lushness certainly serves Jones’ purpose best here. Especially when The Old Mill itself bears an Oscar to its name; clearly, a competent point of reference.

Sniffles and Jones seem to sense this in themselves—an exclamation of “Jiminy Cricket!” from the former is proudly on the nose.

Julian’s backgrounds prove to be a hit yet again, both through the convincingness in their vast darkness (giving Sniffles reason to surmise “It’s sure dark in here!”) as well as concocting a careful frame through foreground objects. Such clutter is carefully orchestrated to guide the audience’s eye along, with Sniffles fitting into the negative spaces erected through tie objects; likewise, the benefit of such clutter encourages a sense of stealth. The lackadaisical manner in which these objects are arranged indicates that they haven’t been touched in some time. Thus, it communicates that we aren’t exactly supposed to be here, which thereby piques the curiosity of the viewer and maintains a sincere desire to follow Sniffles’ explorations.

Amidst his meandering, Sniffles suddenly perks up. Stalling reflects this shift in demeanor with a perky music sting—Sniffles halts, winds his body up, and runs off to the source of his interest. It’s a very cute little beat that is drawn as appealingly as it’s scored, even at the distance it registers; however, the momentum between shots buckles in service of this. A jump cut seems to be the culprit, as Sniffles is suddenly in the middle of the next scene when the camera first moves over to him. Such creates a narrative jolt that loosens the flow of shots, which, in turn, potentially exacerbates the discombobulation of these pauses.

Lighting a nearby oil lamp nevertheless takes precedence. The shift in light is palpable—initiated through a double exposed cross dissolve, both backgrounds, light and dark, are tightly rendered and do read as though they are reacting to the introduction of light. Not a haphazard means of getting to an end, afterimage lingering amidst an equally haphazard dissolve. Advancements made in the camera department within the past few years have truly been staggering.

Content with his handiwork, Sniffles opts to settle down for the evening. Softness in the pile of hay is convincing and tactile; indicating “pillow lines” where Sniffles interacts with the hay plays a part, of course, but the airy (yet organized), fair brushstrokes of Julian’s backgrounds bear just as much responsibility. Even if the inkers still indicated the lines to convey such softness, the effect wouldn’t exactly land if the actual painting of the hay was loose, blobular, stiff. Convincingly placid character acting on Sniffles certainly aids in the illusion of comfort.

Our story as it stands currently has been resolved: Sniffles runs into conflict, Sniffles finds a solution to said conflict. Solution turns to resolution. That in itself is a good sign, in that Jones’ directing and Hogan’s storytelling is concise and comprehensible. However, with five minutes remaining, priorities shift to introducing new sources of conflict—after all, this is The Brave Little Bat. Not Sniffles Finds Some Shelter.

So, aware of this, the camera takes charge in introducing us to the next act by panning up. Jones and Julian utilize their experience on The Egg Collector to prepare for these extravagant, moody, vertical pans through synonymously deserted buildings. Perhaps the effect is even stronger here with the sheer difference in color temperature; such dark, empty, portentous backgrounds are elevated all the more through a direct means of contrast. The atmosphere certainly isn’t as inviting and warm as it was just seconds ago.

Darkness of the background eases in service of our new subject. Wooden beams and the comparative lightness construct a frame that easily guides the audience’s eye right to the center…

…where that eye contact is soon reciprocated.

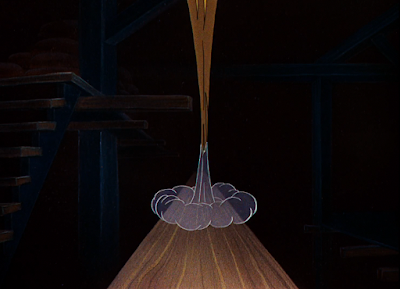

Enter the bat. Shrouded in darkness and shadows, its most discerning attributes are its sharp, glowing eyes. Handling of the shadows could stand to be a bit more thoughtful; the bat is a dark brown-gray rather than complete black, which is a bit asynchronous with its deliberately low detailed rendering. The bat is more akin to a traveling blob than an actual bat in this moment—defining its silhouette and/or using a darker color for its base are possible fixes.

Likewise, it’s descent reads slower on screen than what is illustrated through the sound effects. Viewers certainly don’t receive that same ferocity in the visuals as is reflected in the accompanying sound effects (a raging plane engine). It isn’t so much that the bat needs to be a speeding blur; perhaps the issue could be solved just by losing the sound effects.

The bat nevertheless finishes his descent—right in front of Sniffles. A wooden beam in the foreground divides the scene into two clear parallels: the bat and the mouse. Even a nail protruding out of the wood seeks to concoct a frame around the bat, which is furthered through the lamp handle in the background lingering above his head. Composition is tight, cluttered, and busy in the bat’s half, purposefully helping him to blend in with his surroundings (or, at the very least, remain comparatively indiscernible). Sniffles’ half is wide open. Thus, Sniffles is rendered as a more vulnerable target through such openness.

Tense, clomping footsteps are enough to rouse Sniffles and indicate he has a visitor. His first instinct upon waking up is not to look towards the source of the noise, but gawk at the audience instead; such is a continuation of that viewer/character partnership exhibited at the top of the short, whether it be through his confused blinks at the camera or cheery asides thereafter. Subtle and even mindless as this connection may seem to be, it paints Sniffles in a sympathetic, amiable light, continuously endeared by the audience. It moreover invites the viewer into the action, rendering them more invested by proxy. We aren’t a powerless outsider. Not until we’re supposed to be.

Thus, now on the same physical plane as Sniffles, subject to that illuminating, cozy atmosphere, the audience receives their formal introduction of the bat:

A long lost twin of Sniffles’.

His markedly un-batlike appearance is entirely the point. The dark shadows, the thick atmosphere, the enigmatic movements of the bat—Jones’ establishment of these above aspects purely exist to be radically crushed by the actuality of the bat’s appearance. Cute, chipper, and, with the exception of his wings, looks absolutely nothing like a bat. This almost comes as a detriment, as this “reveal” (or, perhaps more accurately, his existence as a whole) has been prone to puzzle more than entertain. All of the elements are there; the radically different silhouette is a necessity to maintain the surprise aspect, as are all of the differences in demeanor. However, room for commitment to either side (such as making his silhouette more menacing to make the eventual reveal a stark antithesis) still remains. The intent of the bat’s reveal and why he looks the way he does isn’t immediately clear. Jones’ line of thinking is all there—the actualization, not as much.

“Hello!” being the first word out of Sniffles’ mouth certainly speaks to his character. Not a “Who are you?” or even a “What are you?”, no inquiries of what he’s doing here or why he’s approaching him. Instead, his first impulse (after the completion of his politely vacant, contemplative staring) is to greet him with a warm how do you do. No caution or fear to be found. It’s a very charming facet of Sniffles’ personality; he isn’t exactly fearless, but, rather, isn’t aware that reacting in fear to this sudden stranger emerging out of the shadows is even an option. Everyone is a potential friend.

An anticipatory pause as the camera settles back on our bat-rodent hybrid. His all consuming, unblinking stare bestows the viewer with the privilege of momentarily bathing in a swath of questions. What’ll he sound like? What’ll he say? Is he as friendly as he looks? What relevance does he hold? Jones entertains such broiling excitements for a few moments. A first impression is always the most important:

“I heard ya come in, why did’ja come in for? I’m glad ya came in ‘cause I get kinda lonesome in here by myself sometimes ‘cause there’s nobody here but me and now you—where’d ya come from? I live up there and I’m a bat, are you a bat?”

The bat’s introduction is spot on. Through this tangle of breathless inquiries and tangents, the audience is immediately able to paint a picture of what this fella is like and what he does. A youthful, disorganized chatterbox whose thoughts have no rhyme or reason pertaining to how they lead into one another. A large contrast to the polite, unobtrusive nature of Sniffles—their looks are about the extent of their similarities.

His “Hello!” is tacked on to the very end, succeeding a relatively dramatic (yet silent) inhale to enunciate just how much of a chatterbox he is. Likewise, its inclusion seeks to tease his disorganization.

Sniffles forthcoming dialogue may sound somewhat wooden on paper, but is an incredibly well thought out development from Rich Hogan and Jones. His statements of “Heck, no, I’m not a bat. I’m a mouse! An’ I came in here to get out of the rain! An’ my name is Sniffles,” all answer the bat’s individual inquiries in a methodical manner. His constant “And—“ing is supposed to seem stiff; it seeks to juxtapose just how fluffy and tangential and incomprehensible the bat’s syntax is. Sniffles is simple, reserved, to the point. His responses reflect as such.

Establishing the chattiness of the bat is important—how it is executed, even more so. As mentioned above, his endearing obnoxiousness isn’t necessarily rooted in the mere fact that he talks a lot, but how he does; this is made especially clear in his response to Sniffles, where he rambles inanely about being a bat after asking what a mouse is (“What’s a mouse? I’m not a mouse, am I? I’m a bat, aren’t I? But you look like a bat, you look a lot like a bat”). Then, without missing a beat, still on the bat tangent, he finishes with “Is your name really and truly Sniffles?”

A less confident director may have had Sniffles stare at the camera in response to the bat’s spontaneity. Sniffles, however, takes his directionless ramblings in full earnest. Jones allows the bat’s words and demeanors to speak entirely with themselves, encouraging the audience to derive their own conclusions and laugh at what is presented. Forcing any directorial commentary could undermine the growing dynamic between Sniffles and the bat. It may read as more “boring” in comparison, having Sniffles answer all of his inquiries sincerely and without question, but it works to the betterment of what this cartoon is attempting to achieve.

Thus also opens the floor to stunning revelations such as the bat’s name. Which is, of course: Batty, “cause I’m a bat an’ bats can fly awful good an’ I can fly best of all—I’m the best darn flyer in this ol’ windmill”.

Viewers may note that the camera language in this sequence is comparatively stolid regarding Jones’ usual means of composing shots together—a cut to Batty, a cut to Sniffles, a cut back to the same layout of Batty, a cut back to the same layout of Sniffles, etcetera, etcetera. This, too, is rooted in purpose. As much as this back and forth is prone to cause a disconnect, constantly jolting the audience around, it digs those budding parallels between characters into the ground. Their differences in demeanor are acute in their awareness; the harsh cutting marks a definitive juxtaposition, supported through Stalling’s dueling music scores (a soft refrain of “In a Little Dutch Kindergarten” for Sniffles, a breathless romp of Mendelssohn’s “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” for Batty). It’s monotonous on paper, but is not entirely a product of accident.

A brief cut back to Sniffles, less so. “Accident” isn’t exactly the word—moreso “misguided”. Amidst his ramblings, both Batty’s voice and his accompanying music score seem to wilt out of nowhere. Said faltering could stand to be reflected a bit more coherently in his animation, as it initially registers as awkward dialogue, but the shift is nevertheless strong enough for Sniffles to take heed. Communicating this is fine in itself; however, his mouth appears to move as though he had a line or was asking a question. No such dialogue ensues. Looking closer, the lip-sync seems to suggest that he asks “What’s the matter?”

A very minor blip, all things considered, but one is left to ponder what Jones’ intentions were, whether the surviving result is the consequence of some cutting or plain incoherence.

Some of the lack of clarity is intentional. Portions of such directorial ambivalence are a direct consequence of Jones hiding a surprise until the last second—in a flash, Batty springs into action and grabs Sniffles…

…just narrowly missing the impending arrival of a clearly antagonistic cat.

Hiding the reveal of the cat until the last possible second is a great subversion on how these conflicts are usually handled (including from Jones himself). Having a character’s voice trail off, cutting to a point of view shot of some glowing eyes behind the victim-to-be, victim to be asking what the matter is, beat of realization, and a narrow escape was tried and true even as early as 1941. Even if the audience confusion purported by Jones leeches into unintentional excess, the integrity of maintaining the twist and investing the audience into the action by sharing Sniffles’ puzzlement prevails. Very integrative storytelling and directing.

The same vertical layout that accompanied Batty’s initial reveal in the rafters is utilized once again as they fly to safety. While the audience still gets the impression that Batty is much more a mouse with wings than an actual bat, consideration of Sniffles’ weight dragging him down is well done; the flapping of Batty’s wings is much less belabored when freed of his passenger.

Animation of his disembarking is incredibly well handled, both from the arcs that dictate his movement and the fluidity in how he comes to a stop. A playful deftness dominates that does render him more bat like in this moment—it likewise serves as a powerful incongruity to Sniffles’ hunkered posture, barely able to even turn his head. Batty’s stance is proud next to his.

Likewise, how they both process their encounter once again differs: a visibly shaken Sniffles asks what it was they encountered. Batty, in all of his good-natured flippancy, brushes it off as “just the cat”. As he rambles about his ability to continuously flee the cat’s clutches, he inserts more non-sequiturs without even missing a beat (“Didja say your name was really Sniffles and you’re a mouse? What’s a mouse?”).

Flippancy turned inquisitiveness soon turns to pity, as he now consoles Sniffles for his lack of wings (“No wings, poor kid, poor kid… no wings…”); with some brilliant directing on Jones’ behalf, he and Carl Stalling inject a disingenuously sorrowful violin sting on top. A melodrama is conveyed that reflects Batty’s pity—realistically, Sniffles, as well as the audience, don’t seem bothered at all with the lack of wings. To Batty, however, this is a grave travesty. Stalling’s warbling, tinny violin is cloying enough for the audience to understand that it’s reflective of Batty’s off-beat priorities. However, it maintains enough conviction so that if Batty were ever able to hear this omnipresent music score, he, too, would take it as a sincere reflection of his words.

Jones enables Batty and the audience alike to ruminate in the aforementioned observations for a few more beats. Especially since Batty launches into a new spiel with an entirely different tone seconds after; that insertion of a laden pause again enables a stronger tonal contrast.

Batty, in his roundabout ways, suggests that they get a move on. His talkativeness is expatiated once again by means of a cross fade: his voice trails off as he walks away, the camera dissolving to Sniffles in the process, which subtly connotes that the only reason we’re getting some quiet is because the camera had to force itself away.

Sniffles isn’t as keen on leaving as Batty is. Instead of communicating his unease with the heights that haunt him, he nevertheless suggests that he’ll stay put—“I’m very comfortable!” Talbot’s stuttering warble in her deliveries is incredibly convincing. Tarlton’s squeaky voiced deliveries are a blast, especially when knowing they will soon be used in association with Sniffles. However, Talbot was great about hitting such subtle nuances and inflections in her voice, giving Sniffles a convincing warmth that proves difficult to be divorced from.

The nail from which he’s attached to betrays him nevertheless, easing itself loose from the board and plummeting to the ground. Bad news for Sniffles who, in spite of not tumbling to the ground with the nail, now has to grapple with the fact that the nail has turned the cat onto his location. Unbeknownst to him, of course.

Good natured confrontation from Batty ensues as he returns to talk his friend’s ear off: “Whatcha hangin’ down that way for, why d’ya hang by your heels for? I hang by my heels too, but only when I’m sleepy, are ya sleepy, Sniffles? I didn’t know mouses slept that way, Sniffles! I didn’t!”

Layouts are constructed to give Batty a gentle sense of superiority by looking up at him. It isn’t so much that he’s actually above Sniffles in status, but literality. While he’s safe on top of the wooden beam, able to walk it back and forth with ease, no anxiety at doing so, we—that is, Sniffles—are stuck in the purgatory of hanging below him. The communicated superiority isn’t out of pompousness, but safety. He has the luxury of safety and he doesn’t even know it.

That, too, is made explicitly clear through the adjoining sequence of Sniffles crawling along on his stomach. Contented in his oblivion, asks why Sniffles would ever do such a thing: “Do mouses always do that, Sniff? It looks like a worm, that’s what it looks like—didja ever know any worms, Sniff? Are they nice? They look kinda slimy, are they slimy? Huh?”

Sniffles’ silence speaks for itself. Not out of rudeness or disregard for Batty’s presence, but to demonstrate just how concentrated he is on inching himself forward. If he so much as breaks eye contact, disaster could strike. Thus, Batty’s innocent blithering is made all the more endearing given that he doesn’t share that same sentiment of caution whatsoever.

Albeit somewhat obscured through the dim lighting and darkness of the values, Jones arranged the background pan to move at a slightly different interval than the foreground beam and its subjects, thereby rendering the environments more rich and full through the illusion of depth. All the more reason not to fall off. Kudos to Stalling and his methodical, musical inchworm-ing, still clinging to Sniffles’ motif of “Kindergarten” out of continuity.

Another cross dissolve indicates a change in tone and structure. Sure enough, the camera follows the escapades of the cat as it ascends higher and higher, closer and closer to its potential prey. Diagonal, dramatic angles convey a dynamism that translates to unease. The presence of the cat isn’t to be taken lightly—he isn’t here for decoration.

Commenting on his impending arrival, Jones even resists the urge to cut to the next scene of Batty and Sniffles. Instead, they are introduced in one fell swoop of the camera, traveling diagonally and upwards a considerably brief distance. Such subliminally communicates the growing collision of two parties; both characters are now within the same overarching layout as each other. No cut or dissolve or fade to perpetuate the illusion of distance or safety. Conflict is imminent.

Well, almost. A little more time is taken to luxuriate in the differences between Batty and Sniffles: a break in the wooden beams is no match for Batty, who flies over the gap with ease. He barely even seems to register its role as a potential obstacle.

Sniffles could only be so lucky.

More “plink plink” blinks ensue—there’s been a comparatively noticeable reliance on such a piece of acting throughout the cartoon, but doesn’t come as an overly obnoxious detriment. Especially now, when these contemplative pauses are more important than ever in distinguishing himself from his chiroptera comrade. His scenery chewing (which isn’t scenery chewing at all—just in comparison to Batty, who is the opposite extreme) provides the audience with a moment to breathe and a clear juxtaposition in demeanor between the two.

In fact, the scene ends with Sniffles pulling himself back up. No resolution, no shot of him rushing back to flank Batty. How he gets up isn’t exactly a priority. Expressing the sheer antitheses in how Batty and Sniffles approach their obstacles is the main idea. Even Sniffles’ scrambling to safety is comparatively humble given the circumstances—if there was a master of the “character suspended in midair and scrambling for sanctuary”, it’s Chuck Jones, and he knew to elevate any histrionics within when necessary. The idea of the parallel is intended to be the biggest takeaway.

Any gaps in the wood that follow are courteously accounted for through the arrival of a pensive cat. Batty and Sniffles take no notice—Batty in particular utilizes the cat’s nose as a springboard, which falls into the polite antagonization that Jones loved to utilize in the Sniffles cartoons. Sniffles Bells the Cat and Toy Trouble come to mind. Engaging in acts that only perturb the cat further—much to the joyful disregard of the characters—renders the cat a bigger threat through the broiling mental gymnastics therein. He already has mouse-and-bat on his dinner menu; such unintentional abuse certainly doesn’t do much to detract from his plans.

This charade of unintentional aggravation is repeat with Sniffles, albeit in a less physically demanding manner. Instead, he quizzes Batty on the whereabouts of the cat (who is obviously listening and taking stock). Discussions behind his back do little to paint the two pals as angels, even if the extent of such inflammatory remarks isn’t very far. Just Batty commenting on how he “couldn’t possibly climb way up here”.

Batty’s role as a “guide” is, again, well handled by Jones and Hogan. His reassurances to Sniffles convey a backstory of some kind—there’s a confidence to his decrees, a certainty in his deduction that the cat can’t make it up. That in itself communicates prior run-ins with the cat (as conceded by Batty himself earlier on)—it gives the character a richer sense of depth and makes the environments seem more lived in, experienced, nuanced. Even if these implications aren’t incredibly intricate, their inclusion nevertheless makes for a richer cartoon than if they had been absent.

Implied experiences are important. Not just for expelling reassurances, but for the ability to know when to run away. A mirror to the cat’s introduction, Batty’s voice and body language falter as he comes to terms with his uninvited guest. He may be naïve and heedless—that certainly doesn’t translate to stupidity.

A quick technical aside; the camera closes in to focus on Batty, both to divide attention to his dialogue and the manner in which he visibly wilts in real time. This in itself is fine, but does seem a bit stilted regarding the flow of the scene as a whole—the camera zooms back to its original registration in no time. Batty’s reactions are important (especially as they indicate that he’s going to leave Sniffles to fend for himself, backing away off screen), but the scene probably could have fared just as well without the truck-in. All eyes would nevertheless remain on him.

In any case, focus shifts back to Sniffles and his kind, caring nature. He is the one who adopts the role as the metaphorical authority figure, reassuring Batty that there’s nothing to be scared of. In fact, his exact words are “There’s nothin’ here to hurt’cha!”—“hurt” doing a lot of the heavy lifting, seeing as there absolutely is something there to hurt him. Especially when it opens its jaws as Sniffles expresses his sentiments.

The threat of the cat thankfully doesn’t undermine the warmth and genuineness in Sniffles’ deliveries. Stalling’s music score takes sympathy to Sniffles—another gentle reprise of “Kindergarten”—to delegate narrative focus to him. Such is a reflection of his ignorance; unaware of the cat’s presence, his demeanor is light, warm, amiable. Remaining convicted to this demonstrates his good heart… just as much as it prepares the viewer for the brewing tonal whiplash. An anxious, laden music score would benefit someone like Batty in this instance, who is acutely aware of the threat in front of him. For now, even if it’s just a second, ignorance is bliss.

Yet, as they say, all good things must come to an end, and Sniffles is quick to share Batty’s gut-dropping cognizance. A double-take mingling with a surprised sting, Sniffles unconsciously presses himself face to face against the cat to verify that what he is seeing is the truth. There’s no mistaking that eye contact.

Just as there is no mistaking Batty’s cowardice: a purposeful betrayal of the cartoon’s title. In his defense, there is an innocence in his desire to escape. He isn’t purposefully leaving Sniffles to die—especially not when he saved his skin just minutes ago. The desire to admit defeat is just all too alluring. As mentioned earlier, he knows when to retreat. He even attempts to make pleasantries on his way out, a flimsy excuse serving as a more admirable means of an exit than leaving entirely. There’s an attempt to be considerate. How it actually translates and affects the scenario is another story, of course.

“Well, goo’bye Sniff…” Jones deliberately frames the composition from Sniffles’ point of view for further sympathy. In this moment, we are Sniffles. We witness in real time as his—our—safety net actively abandoned us. “I gotta be goin’ now, I gotta very important engagement at the dentist…”

Tarlton’s mechanical, stilted “Ha… ha…” is delivered perfectly.

As is the animation of his departure. He isn’t even a smear so much as he is a streak of paint cascading off-screen; the middle narrows as he ascends higher (and the dust left in his wake expands), creating a palpable sense of force and tension in the way he travels. Its urgency is more than convincing, but still rendered playful through such exaggeration. And, of course, the most important of all: it looks nice.

The reveal of Batty’s house—a birdhouse—is made particularly effective through the restraint of the camera. Rather than flipping upside down to be level with Batty, Jones instead allows the action to thrive as it is. Batty speeding into his house and pulling the curtains closed is coherent and easy to decipher regardless. Additionally, keeping the house upside down communicates a very brief disconnect that plays into his abandonment of Sniffles. We (Sniffles and the viewer) do not live in these upside down houses that Batty does. Jones makes no directorial accommodations to bridge the gap. No matter how slight, a very purposeful dissonance lives to exacerbate the alienation of Sniffles occurring on screen.

Nevertheless, out of the goodness of his heart, Sniffles doesn’t take too much offense to it. Attempts to mimic Batty’s exit take precedence, touting his own “‘portant ‘gagement” as an excuse. Smugness on the cat’s face is unmistakably Jones.

Conceit that trickles into his acting, too—the plank that Sniffles is walking on isn’t nailed down to anything, which grants easy access for the cat. Any other cat would lunge at his prey and take care of matters right off the bat. Not the cats of Chuck Jones’ world, who prefer to indulge in more gradual, decidedly human gestures whose anticipation is agonizing for the victim.

As he’s in the process of doing so, Batty meekly peers out of his window. Such asserts that he isn’t a bad egg; there’s a cautious concern for Sniffles’ well-being, and an awareness that he left him to the clutches of the cat all his own.

So, who better to save Sniffles than the one who left him in such circumstances to begin with. Thus initiates the cartoon’s climax: Jones repeatedly cuts between shots of Batty flying through the air and the cat lowering the plank near his mouth, the fragmentation conveying a jumpy urgency as audiences get a glimpse of both simultaneous actions. Frequency of the cuts could stand to be just a bit quicker, but remain coherent and fine as they are. Cutting too quickly offers more room for disaster than the alternative—Jones seemed to be aware of this.

Now serving as a genuine reflection of the cartoon’s title, Batty swoops in to draw Sniffles out of the clutches of the cat. Just in time, too—the cat is quick to accidentally indulge in a mouthful of splinters. Prominent, red gums amidst his sharp fangs render him all the more menacing; the audience is encouraged to imagine about Sniffles in the wood’s place. Batty’s cooperation certainly isn’t taken for granted.

There seemed to be an understanding that having the chew on some wood isn’t the most rewarding payoff. An astute observation, but the following actions to make good on that read as somewhat obligatory and “easy”. Discontented with the outcome, the cat angrily stalks off…

…only to forget the laws of gravity. Timing of the fall over the edge comes a bit too quickly, furthering feelings of this topper seeming compulsory and even a bit mechanical. Likewise, the reactions from Batty and Sniffles—politely observing from the safety of Batty’s home—could stand to be a bit more grandiose. Nothing melodramatic, but indicative of the loud crashes and bangs and snaps completely dominating the short’s soundtrack for the next 10+ seconds. Their blinking and flinching is spontaneous, a bit stilted, not a direct reaction to anything actually occurring.

Nevertheless, as is always the case, the main idea is clearly communicated: the cat isn’t a nuisance any longer. Such is expressed through a shot of the outcome—a positively bedraggled, disgruntled feline contained to an oil lamp, momentarily powerless. With all of the build-up established within the past few minutes, there could stand to be a greater payoff—regardless, the drawing of the cat is certainly powerful and amusing. If this is the note Jones is going to end on, then it’s a well suited drawing.

We only have one more piece of business to attend to. A cross dissolve takes the viewer back to Batty and Sniffles, where Batty has much to say on the matter. Asking how the cat ever could have gotten up there, how can cats climb that well, etcetera, etcetera. In all of his warm ways, Sniffles listens in amiable interest and attentiveness.

Mostly.

Referring back to the introduction, The Brave Little Bat is probably the best candidate to put Talbot’s Sniffles to rest. Batty’s character inadvertently prepares both the audience and Jones himself for what’s to come of the remaining Sniffles cartoons—even if both of them had no idea this would be the case at the release of this cartoon.

Quality of the short itself is certainly a big factor in this satisfying closure of a chapter. Like every cartoon, the short boasts its fair share of vulnerabilities: the climax could stand to be a bit more engaging, particularly when handling the cat. His resolution seems thin, obligatory, brief, a bit unbalanced. Then again, the main conflict of the short (avoiding a run-in with the cat) isn’t even thought of until four minutes in. Establishing the characters, setting, and atmosphere was clearly Jones’ directorial priority, and all of those aspects sing the most in this cartoon. So concerned in expressing the differences between Sniffles and Batty and so concerned about setting up a comfortable environment, the need for an actual conflict with a firm resolution lags behind.

Perhaps such a deduction is owed to the short’s obedience to its own self-made formula. Most of the Sniffles cartoons to this point feature synonymous cats with synonymous mannerisms and synonymous desires. This sudden appearance and inclusion of the antagonist may be more gripping for someone who isn’t as well acquainted with the set-up of these cartoons as we are. Perhaps this in itself indicates that a change in Sniffles’ handling is overdue.

Even then, that isn’t entirely the case. It proves difficult to wholly label the Sniffles shorts pre-1942 as “formulaic”, because Chuck Jones has gone out of his way time and time again to disregard formula. Sniffles is even his own adversary in Bedtime for Sniffles. Likewise, Sniffles Takes a Trip is comparable to this one in its proud embrace of atmosphere and environment. No feline adversary to haunt him in that cartoon, either.

It is genuinely difficult to bid farewell to Talbot’s mouse. She was the perfect companion for Jones’ intent with the character, and maintained a natural warmth and friendly, meek charm that prevented the character from dipping into the symbol of mawkishness that most see him as. For all of her excessive talents, casting someone like Berneice Hansell—an expert at cloying baby voices, whether out of an obligation to compete with Disney in her mid-‘30s cartoons or to annoy the audiences out of their minds, as Tex Avery often used her for—would have rendered Sniffles a much more insufferable character if played in earnest. Not that Hansell is insufferable, but she didn’t exactly fit the humbleness unique to Sniffles. Hansell’s vocal talents can be heard from just about any cutesy character in the ‘30s. Talbot, not so much—thus demonstrating that Sniffles isn’t conceived out of the same maudlin like so many other of his contemporaries.

However, this short alludes to a bright future. Tarlton proves to maintain a versatility with her own constant babbling; incredibly faint vestiges of Talbot’s Sniffles are still present in The Unbearable Bear, where he’s consumed with a good-natured overzealousness rather than full on obnoxious blabbermouth. Sniffles in Hush My Mouse, on the contrary, is almost an exact mirror to Batty’s behavior and dialogue here.In any case, The Brave Little Bat proves to be another strong effort in the Sniffles series. Even with its weaknesses, it’s charm, warmth, and sense of purpose in directing and characterization (such as Batty, who isn’t obnoxious because he talks a lot—it’s how he talks, it’s how he conducts himself, and Jones is careful to make sure that this obnoxiousness is never fully frowned upon or too grating for the audience) prevail. Paul Julian’s backgrounds are at some of their moodiest yet. Stalling‘s score remains attentive as ever, the assignment of independent musical motifs for Sniffles and Batty really driving home those parallels so quested by Jones in his directing.

Contentment from Sniffles proves contagious; he’d be comfortable with this as Talbot’s last outing, and thus, so are we. A comfortable, warm note to end a chapter of Jones’ directing history.

.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment