Disclaimer: This review entails racist content and imagery with the intended use of historical and informational context. I ask that you speak up in the case I say something that is offensive, harmful, or perpetuating so that I may take the appropriate accountability. Thank you.

Release Date: October 25th, 1941

Series: Looney Tunes

Director: Norm McCabe

Story: Tubby Millar

Animation: Vive Risto

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Porky, Mouse, Friday), Sara Berner (Baby Snooks), Robert C. Bruce (Announcer)

(You may view the cartoon here.)

Artistic evolution is constant. It may not always be linear, and how something evolves can often be a subjective matter in the world of art and film-making (such as the adoption of the UPA style of cartooning throughout the ‘50s; some were more welcoming of this change than others). Likewise, there may be periods where there doesn’t seem to be any sort of growth at all: just directorial stagnation.

These past few months—really, the whole year—have certainly been illuminating regarding the growth of the Leon Schlesinger studio. Shorts are becoming more recognizable in their maintenance of the Warner Bros. identity. Jokes are landing harder, quicker, more cleverly. Characters (such as Bugs and Daffy) are finding their footing and making good of it. Growth of the studio is undeniable.

However, even with all of this in mind, perhaps there is no greater reminder of that constant change than the implementation of a new director. A reminder that there is momentum behind the scenes, thinking and planning occurring for the betterment of the cartoons. This isn’t to insinuate that cartoons only grow if there is a new director in town; especially given that the entirety of the ‘50s—with the fleeting exception of Abe Levitow—was dominated only by three directors. That in itself could be indicative of growth: a security in knowing that the studio could survive with the talents of only three directors. An indication of stability.

All of this grandstanding is to formally introduce Norm McCabe, who is the first new director on the scene since Chuck Jones in 1938.

Up until this point, McCabe was most known as an animator in the Clampett unit, having been a part since its inception. His loyalty landed him a co-director spot in late 1940 after Clampett suffered a bout of illness and needed someone to finish up two of his shorts: The Timid Toreador and Porky’s Snooze Reel respectively. Such experience helped to prepare in being the formal successor to the Clampett unit, better known in the studio as the [Ray] Katz unit. In fact, his adoption of the unit would see the dissolution of the Katz unit, as he and his animators moved back into the main studio building. McCabe’s time as director followed the same trend that largely contributed to some of Clampett’s directorial burn-out within the past few years, in that McCabe purely directed black and white cartoons.

McCabe’s relevance to the studio—and the industry as a whole—stretches beyond his loyalty to the Clampett unit. First hired as an in-betweener under Hugh Harman and Rudy Ising’s tenure in 1932, he rose up the ranks to a full-time animator in 1936 under the direction of Frank Tashlin. It’s worth mentioning that Frank Tashlin himself would adopt McCabe’s directorial unit in 1942 after McCabe was drafted into the military.

By the time the war ended, the studio had reached capacity and didn’t have room for McCabe to return. While he never directed at Warner’s again, he is offered a joint producer and director credit on the 1946 short Honesty is the Best Policy—an effort from the short-lived Planet Pictures and Oscar Productions. Don Yowp offers more insight on the venture here.Directing for All Scope Pictures in the late ‘50s, McCabe found himself reunited with some old friends in the ‘60s, working as an animator under the reign of DePatie-Freleng. He contributed to a handful of their films at Warner’s, before following them to their own fully formed studio and working on such properties as The Pink Panther.

Intricacies of McCabe’s directorial career—his quirks, his tone, his overall sense of direction—will be explored to a greater degree of depth as as we submerge ourselves deeper into his filmography. For now, our priorities lie with Robinson Crusoe, Jr. It is almost surprising that the studio hasn’t attempted to riff the source material prior—there is certainly a reason why it has likely never been referenced in a cartoon past 1970, but it was ripe for parody from multiple cartoon studios in the ‘30s especially.

In fact, despite there never being an animated parody of the story from Warner’s, this isn’t Porky’s first time in the role of Robinson Crusoe. A handkerchief released in the ‘30s depicts Porky as a chipper, innocent Robinson Crusoe, joined with man’s best friend (who bears a striking resemblance to Porky’s Duck Hunt’s Rin Gin-Gin—one of a handful of characters who Schlesinger attempted to market, perhaps puzzlingly so.) My personal guesstimation of when this dates to would be 1937-1938, with a particular emphasis on the latter—the source claims that there is an accompanying piece with Petunia, which seemed to be a theme of merchandising released in 1938, such as a Porky and Petunia coloring book.Times have changed, of course, and McCabe’s Porky of 1941 is initially less content with his shipwrecking than his smiling, hand-sewn counterpart. His retelling is somewhat more modern, but relatively true to the source material: a shipwrecked Porky makes the most out of his newfound island life, until a run-in with a group of natives puts him in jeopardy.

Interestingly, this cartoon makes a point to stick to its roots as a novel. Much of the story is divided into segments: a cross dissolve to the page of a book, implied to have been written from Porky’s perspective. That then segues into the resulting scene realizing the written prose. For example, the short opens with the passage discussing preparations to sail.

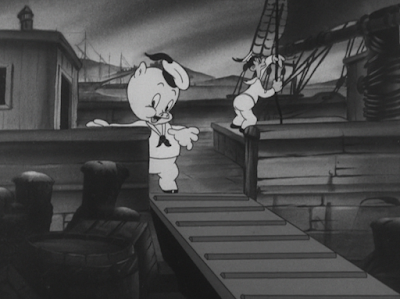

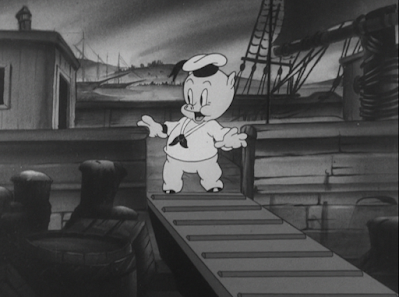

Sure enough, the text lifts to reveal Porky in his sailor’s garb contentedly observing as a gob raises the sails. It’s a rather novel format that hasn’t really been seen in the Warner shorts before, and was seldom replicated thereafter. Chuck Jones structures a few of his shorts—Rocket Squad and Deduce, You Say, both 1956 efforts—with occasional bouts of verbal first person narration, but even that is a bit of an exception.

These written interstitials were probably as much of a directorial cheat for McCabe as they were a clever ways of paying homage to the original book; instead of fretting over how to initiate a certain scene, how to ensure they hook-up together clearly and coherently, he could momentarily solve such woes by means of written narration filling the gap. It does read more as a conscious nod to the source material than it does as a cop-out, but those aforementioned benefits probably weren’t lost on McCabe.

If one were to view this opening scene alone with no idea of a director’s credit, they may be inclined to pin this down as a Bob Clampett cartoon. Porky (animated by John Carey, who continued his role as character layout artist for McCabe like he did for Clampett) is indistinguishable from his appearances in Clampett’s shorts, Dick Thomas’ backgrounds are indistinguishable—the only real giveaway tends to be the designs of the humans in McCabe’s shorts. There are obvious exceptions to this throughout his filmography, but, as of Robinson Crusoe, Jr., the resemblance is uncanny.

Going back to the background paintings comment, sharp eyes may notice that the main background painting behind the boat suddenly seems to change. Riding on the coattails of a cross dissolve, the camera trucks out to reveal the entirety of the scene as the audience becomes acclimated to the setting: it is then when the horizon suddenly snaps to a new painting. A new painting that actually isn’t a new painting at all—just the same background pan at a different angle. The error is nevertheless disguised through the camera movement and visual focus on the animated characters.

“Geh-gee-eh-gosh, I guess we’re ready to em-eh-buh-buh-bar-ehm-eh-buh-be-beh-beh-be-eh-behh... shove off!”

Porky’s direct acknowledgment of the audience ties—if only tangentially—into the first person narrative with the book vignettes. As expounded upon in dozens of reviews, characters addressing the audience is second nature in these cartoons. Some characters are particularly reliant on these constant metaphysics, whose audience acknowledgement is as habitual as breathing. Daffy in particular is a great example of this; McCabe’s Daffy would likewise lean rather heavily into constant audience interaction.

Given that the end of every Looney Tunes short boasts Porky directly addressing the audience for a 9-year streak, his conversing here certainly isn’t out of his league. It is a bit more of a statement and less ingrained as an impulse with him than it is to someone like Daffy—the eye contact and conversing feels incredibly deliberate. Perhaps too much so, as this exchange almost feels stilted in its candidness. McCabe’s intentions allow the audience to fill in the dots with the behind the scenes—we don’t need to see the construction of the boat or how Porky became a gob or any of that expositional fluff. However, in ensuring a natural and organic opening that doesn’t feel spoon-fed, there is almost a very slight dissonance in the directing. There isn’t much action on screen that seems to warrant Porky’s comments outside of the sailor raising the mast, but even then, that certainly doesn’t feel like any kind of initiator.

Robert C. Bruce plays the brief role of a monotone announcer, drawling “Aaaaall ashoooore that’s going ashooooore!”—perhaps then would be the best opportunity to insert Porky’s line. A loud, sharp, metallic clanging sound resonates off-screen before Bruce’s line, to which Porky visibly flinches—this, too, is relatively unclear as to what the intent or even source of the sound is.

In any case, priorities soon shift to the hoard of mice swarming off of the deck of the ship (those interested will note a brief cel error on Porky for one frame)—they, too, are exceedingly identical to the many mice seen in Clampett’s cartoons.

Particularly in the adjoining close-up, where an anthropomorphic father rat drags his daughter off the ship. The Blanc-voiced mouse namedrops Fanny Brice’s character of Baby Snooks: like many stars of the radio, her likeness was caricatured time and time again throughout many a cartoon—Chuck Jones’ Quentin Quail in particular dedicated an entire short to the dynamic between her and her father, portrayed on the radio by Hanley Stafford. Their referencing here is one of the first for Warner’s.

Upon the Snooks’ mouse’s inquiry relating to why they must leave, McCabe and writer Tubby Millar indulge in yet another pop-culture pull, whose often punny variations (as is the case here) can be found in many a short: Mischa Aeur’s “Confidentially… it stinks,” from the 1938 film You Can’t Take It With You is, of course, recontextualized as “Confidentially, it sinks”. This embrace of popular and beloved references is yet another aspect that renders this short relatively synonymous to Clampett’s efforts, who certainly touted no shortage of material in his own timeliness and love of pop culture.

Porky doesn’t seem keen on indulging in that same appreciation. His huffy, aggrieved dismissal of “Ohhh… eh-wuh-weh-what do rats know about eh-boats, anyway?” is indicative of the sprouting cynic that would come to light throughout the next handful of years. His offense is quick to dissolve as the boat begins to move, eagerness at the voyage much more in line with the pig we have become accustomed to, but it doesn’t seem likely that such a moment of “vulnerability” would be in the short had it been made two, three years prior. Maybe a passing frown if the directors even chose to acknowledge the cutaway at all.

With that, the voyage sets sail, and Porky makes the most of his audience awareness bidding us adieu. His “So long, ev-ah-buddy!” is orated with such a specific inflection that it has to be a reference of some kind—one that is unfortunately lost on myself. Nevertheless, it does certainly seem as though Porky is addressing the theatergoers directly, given that it doesn’t seem like the voyage itself is receiving much on-screen fanfare.

McCabe uses this opportunity to enlist in another passage as a transition. Note the “Chapter VI” in the top; throughout the cartoon, the order of the chapters are in subtle disarray as an in-joke in itself.

The specificity of nine weeks unintentionally renders Porky’s forthcoming musings hilarious, as we dissolve to find him muttering “Those eh-ehs-silly rats,” to the audience. Thus unconsciously implies that Porky has spent over two months ruminating and taking offense to his ship no longer deemed infested with rats. Amusing and perhaps unintentional as the circumstances may be, that stubborn embrace of a grudge certainly wouldn’t be alien to Porky’s character. For better or worse, whether out of pleasant oblivion or affronted disgruntlement, Porky is a character who sticks to his ways.

“It says right here, eh-geh-gg-guaranteed absolutely unsinkabuh-beh-buhh-eh-buh-beh-ehh... ehhh—safe.” McCabe was clearly making the most out of Porky’s speech patterns, leaning into the ol’ switcheroo as though it’s a rite of passage when directing the character. In a way, it is.

A little bit of awkwardness manages to inject itself into his animation, but that could just as well be a byproduct of the bread-and-butter writing. His expression is a bit unintentional in how vacant it is, and his fingers are oddly tapered/long/skinny for his build—little things, in the end. A pause lingering on these aspects once he’s finished talking doesn’t do much to call attention away from such discrepancies.

That aforementioned bread-and-butter doesn’t seem entirely sincere. The gag is the convenience—Porky’s musings of “I wonder if that eh-guh-gih-goes for hurricanes” logically summons said hurricane just seconds after. Nevertheless, the directing could benefit from a more clear sense of purpose. Eliminate the pause between actions, do something to intensify the storm and stress how much it was waiting for Porky’s cue. The ingredients are all these, as is the basic understanding of what’s happening: they could just use a bit more to make them feel at home.

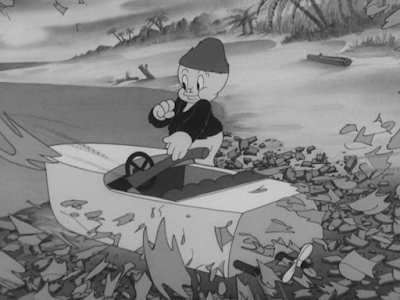

All of this may be a misdirected critique that instead applies to the actual execution of the storm itself. It succeeds in convincing the viewers of its violence—blinding flashes of lightning, a tense music score from Stalling, startled reactions from Porky, but bears the same notes of feeling a bit too obligatory. Both Porky and the boat seem to rock around aimlessly before the camera dissolves to the outcome. Given that the short is moreso focused on Porky’s inhabitance of the deserted island and how he makes do (rather than how he got to the island to begin with), it’s understandable that the storm be short and to the point, a piece of exposition. Still—it seems to beg for something more, whether that be a stronger commitment to theatrics or inserting a quick visual gag or two.

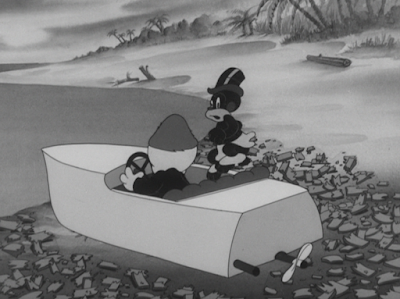

Nevertheless, the consequence of such turmoil is one of the short’s directorial highlights. McCabe allows every action to speak for itself and for the simplicity to prevail: the tonal matter-of-factness is practically a joke in itself. What else could possibly become of such a violent hurricane other than a marooned Porky lying disgruntled among the wreckage, skies almost insultingly clear and free of clouds nor rain? John Carey—once again the animator of this sequence, whose drawings continue to follow the trend of being the most appealing drawings in the short, especially now that McCabe himself is no longer an animator—even includes water dripping off of the seaweed above Porky’s head to indicate that the damage, both physical and emotionally, is still rather fresh.

“I had ta open my buh-bih-eh-big mouth,” clinches the earlier observations about the triteness of Porky’s remarks.

Carey’s character acting and draftsmanship is again deserving of praise. He captures Porky’s steely brooding and status as the victim of a wounded pride succinctly with slow, contemptuous movements—the gradual sliding of his pupils to make eye contact with the viewer, his contemplative fiddling with the sand (which is a maneuver in itself that acknowledges his circumstances: playing with sand means sand to be stranded on, which means he is forced to reconcile with his fate that those dratted rats were right about the boat’s fate), and general demeanor of dripping malaise. Among many other things, Carey had a knack for capturing these subtle moments that required a more careful and attuned animator. While not to discredit their contributions, the effect wouldn’t have been the same if Izzy Ellis or Vive Risto were cast to do the same scene. The tightness in Carey’s work really seems to sing.

Subtle footprints around the area Porky crashed catches his eye…

…as do the larger, deeper, fresher prints in front of him, revealed by the camera as Porky is first studying the initial, dull set of prints before him. Again, Carey’s depiction of this creeping, growing realization is incredibly well handled. Slow and gradual, but not to a degree of sluggishness. You can really feel Porky begin to perk up in real time.

Especially when realizing that the source of said footprints is right in front of him. Likewise, such offers an answer as to why the children of today don’t grow up with dozens of Robinson Crusoe parodies as they did in the ‘30s and ‘40s.

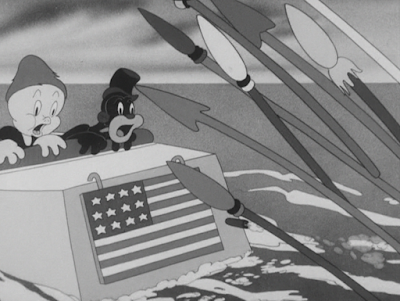

McCabe somewhat subverts the story by channeling a different avenue of racist stereotypes. That is, Friday serves as an informal caricature of Eddie “Rochester” Anderson, most notably through Blanc’s vocal portrayal. His top hat and spats are certainly unique to this particular portrayal, leaning into a comedic—if not unnecessary—formality. Likewise with the handmade sign heralding Porky’s arrival, implying he’s been waiting for this moment long enough to curate a reception.

That, too, is proven through his own dialogue: “H’lo, boss! What kept ya?”

Another opportunity to indulge in more transitional exposition. Porky’s implied comments on settling down to “the usual routine of living” is pretty amusing when discovering said routine amounts to a comparatively showy song number: obviously not too usual nor routine.

Egregiousness of Friday’s existence aside, the song number is as chipper and catchy as it can be, another memorable takeaway from the short. It marks the first instance of The Inkspots’ "Java Jive" in a Warner cartoon—a relatively notable development, given Stalling’s frequent utilization of the score in the coming year or so. All things considered, versatility of Blanc’s vocals deserve commending—he somehow manages to keep the Rochester intact as he sings, and is doubly impressive when it comes out sounding good. The stereotypes and caricaturing are unfortunate, but Blanc’s abilities can’t be underplayed in their quality.

Lively animation is certainly beneficial to the quality of the number, too. John Carey yet again does a particularly fine job on the scene of Friday using the turtle as a washboard, as both characters are approached with a powerfully snappy synchronicity. Such is especially noticeable on the brief musical interlude, where a strong coherence to the musical beat and desire to keep the visuals interesting is at its most important.

Porky contributes his own solos throughout the song which are notably spoken. The first instance is somewhat awkward, as it results in a few bloated moments of “silence” where he aimlessly pumps his arms to the music. It almost feels as though another stutter gag could be used to help fill in the airtime—perhaps McCabe was trepidatious about overindulging, given that he’s done two stutter gags already.

Likewise, some of the dance moves feel a bit stock, aimless, mainly the turtle’s (and Friday’s) finger wagging, as well as the sideways galloping they indulge in beneath the clothesline. Like everything, it’s much more harmless than not. The song is still fun, the musicality is still preserved, the energy is still strong. It likewise doesn’t present itself as a sequence that needs incredibly intricate, true-to-life dancing. The musical interlude is certainly appreciated and one of the short’s most memorable takeaways. Yet, (and this isn’t a critique unique to McCabe’s directing, but could apply all over) it does feel as though there could be just a bit more pushing and pulling and finagling to really make the number flourish.

Utilizing the clothes line is a clever finish. Cheeky and playful, it accentuates the flashiness of the song that McCabe is quite aware of, just as it makes a point to utilize the environments and context unique to this short. It moreover offers room for one final gag—the turtle and Friday switching “clothes”—that gives the audience a sense of satisfaction in its closure.

Through the courtesy of a particularly punny passage transition, the short now settles into its second half: Porky exploring the island. It’s almost amusing at how conveniently Friday is stowed away from the short—a decision that the cartoon probably benefits from, but it does seem to somewhat transparently indicate that McCabe’s directorial priorities are not with him. Again, something that is probably for the better.

Instead, the cartoon delves into a pseudo-travelogue, seeing as a number of spot gags dominate the next few minutes. Porky serves as the narrative glue that somewhat holds it all together, initiating and even reacting to some of these vignettes, but the story aspects of the short do take a bit of a backseat for now.

McCabe and writer Tubby Millar get a head start on their gags even through exposition. A F.H.A. sign tacked proudly against the hut remains firm in its placement since the original introduction of the layout, contributing a coy sense of domesticity that is proudly antithetical to its surroundings. The hut likewise doubles as a pseudo-elevator, thusly answering any questions as to how Porky and Friday can get in and out. Gags that are especially tame by today’s standards, but nevertheless successful in establishing the lighthearted tone McCabe would be chasing for the next few minutes.

Gags such as Porky patronizing a parrot. The acting—both animated and vocally—is well done, whether it be the oblivious, politely entitled condescension of Porky’s repeated “Eh-puh-peh-eh-Polly wanna cracker?”s or the bird’s aggrieved reactions to said condescension. Tree branches and palm leaves construct a careful and conscious frame around the bird to give further clarity to his actions and balance to the overall composition; that way, the audience can watch as he visibly shies away from Porky, who only grows more insistent on his patronization.

“Say, why don’t you answer?” The amusement stemming from the reality of Porky talking to a bird in the wild and demanding it talk to him is certainly not lost.

Of course, his assumption is correct, given that this is a Looney Tune starring Mel Blanc, and Mel certainly had an armada of parrot impressions under his sleeve throughout his career. His response of “I’m waiting for the 64 dollar question!”—a phrase fans of Warner Bros. cartoons may recognize from other shorts—stems from the radio show Take It or Leave It, still pretty novel by the time of this short’s release, and was renamed to The $64,000 Question in 1950.

And that answers that. McCabe closes the scene with a fade to black, communicating a strong air of finality that somewhat renders the punchline more secure. Porky’s vacant stare to the camera is telling and appealing—note the detail on the pie eyes, whose association with Porky was increasingly fleeting at this point in time.

On the topic of throwbacks, the next selection of music that accompanies Porky’s trek through the jungle is “Nagasaki”; a staple of the ‘30s shorts that, while catchy as ever, was subject to Stalling’s ever constant list of inspiration and indulgence in what was most popular at the most current point in time.

Of course, it serves as a passing snatch rather than an entire, fully-realized orchestration: McCabe directs our intention instead to the tall grasses that Porky parts to take a peek. Another pause manages to linger a bit longer than necessary between his parting of the grass and addressing the audience, making said addressing feel a bit less organic, but again remains inconsequential.

Since there is no Robert C. Bruce to guide us along our spot gag journey, Porky momentarily adopts his role with a lesser air of formality: “There’s a lot of wuh-weh-eh-wild animals over there at the water hole!”

Enter said animals. Some of the creatures are approached with a specificity that is again comparable to Clampett’s design sense, with the most notable examples being a bird with and elongated neck and the cute little tiger cub, who is given a bit of a spotlight with his extraneous pushing and pacing about amidst the crowd.

Their rapid fleeing provides a glimpse at the watering hole, which is conducting with similar sensibilities regarding Porky’s base (like the FHA sign outside of the grass shack). Modern amenities that are proudly out of their element in the wild. Here, the empty paper cups scattered in the wake of the stampede give a sense of purpose to the water cooler outside of being a general decoration. It implies a purpose, a history, that the animals were having genuine water cooler chat.

This, too, is clinched through the tiger cub’s return and tidying of affairs. Placing a focus on the antics of a particularly—yet in offensively—cutesy character is certainly constructed in the Clampett mold, and does read as a tangent that could comfortably fit within the context of his own cartoon. Disposing of the cups into a nearby trash can (branded with the “keep your city beautiful” moniker, no less) wraps the entire sequence together in its embrace of modern conveniences.

Drawings of the cub itself aren’t the most earth shattering in their draftsmanship or motion, but still get the job done. The silhouette on the cub as he gears up to run, his tail and back completely connected, is incredibly sharp and a rather conscientious detail. If only the rest of the cub’s animation was so sharp.

More exploration of the island nevertheless ensues. The startled take Porky does after spotting something off screen is handled exceptionally well; he doesn’t come to a complete stop, but instead continues to lean forward ever so slowly. That, in conjunction with the camera refusing to pause for the halt, garners a reaction that feels sincere and motivates rather than a stock obligation of acting. Likewise, the short doesn’t come to a crashing halt to enunciate a fleeting emotion for 1 second before moving on. Such pauses may be inconsequential, but they really do play a considerable role in how the audience interprets the scene and the flow of the cinematography. Constant pausing can become taxing.

Introduction of a telescope once again falls in line with similar gag sensibilities touted all throughout the cartoon: the availability of these modern, often domestic amenities on a deserted island almost free of human life. McCabe approaches these gags with such a nonchalance that they may even have the potential to get lost in a more modern context. Or, at the very least, it would seem more apparent that this is something to laugh at upon its 1941 release—our standard for humor has certainly changed.

Robinson Crusoe, Jr. continually asserts itself as an integrative and collaborative cartoon. As mentioned earlier, this is a habit with McCabe’s cartoons especially, with characters consistently addressing the audience or other fourth-wall breaks that make a point to immerse the viewer into the action. Here, that is delivered through a point of view shot of Porky looking through the telescope. It’s certainly no groundbreaking demonstration of staging that has never before been seen, but it does certainly feed into his prior addressing and acknowledgment of the audience. Not only do we have the privilege of his company; we have the privilege of peering right through his eyes.

McCabe likely took this into consideration, but the benefit of some new, creative staging to break up any potential monotony was probably a greater factor. This iris frame from which we look into offers more room for more gags—gags that can be dismissed as soon as they’re started under the guise of being viewed through a passing glance.

Like monkeys playing poker. A pretty innocuous scene that bases its humor off of the same principles as the rest of the cartoon, but is made appealing through—surprise—John Carey’s animation. His draftsmanship is the biggest takeaway, but timing the movements of the monkeys to be varied and operate at casual intervals keeps it interesting.

Panning of the telescope initiates a switch in animators, now focusing on a different monkey struggling to climb a tree. Carl Stalling carries the scene more than anyone, giving the animation a tangibility through his accompanying music score. While the scene is inoffensive, it is just as arbitrary and doesn’t really feel deserving of the amount of time the camera focuses on it for.

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment