Release Date: October 25th, 1941

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Friz Freleng

Story: Dave Monahan

Animation: Dick Bickenbach

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Reid Kilpatrick (Narrator, Gunner), Mel Blanc (Sergeant, Private, Gunner, General), Billy Bletcher (General), [presumably] Tedd Pierce (General’s Aide)

(You may view the cartoon here!)With the war growing more intense with each passing day, U.S. involvement creeping closer and closer, golden age cartoonists from coast to coast directed their commentaries, thoughts, feelings, and observations into cartoons. Some to explicitly spread a good ol’ fashioned dose of jingoism—most of whom the product of a post-Pearl Harbor world—and some to just take the edge off.

Rookie Revue falls into the latter. It isn’t so much a formal propaganda short as it is a mere wartime cartoon: it’s a rather similar parallel to the upbeat song and dance shorts so rife amidst the heart of the Depression. Shed some of the formalities, encourage a lighthearted perspective and perhaps reassure some of the audience’s nerves in the process.

Of course, those deductions are easier to direct to a comparatively leisurely short like this one, where the conflict of the war is a catalyst rather than an entire focus. This short marks Friz Freleng’s second formal foray into the spot gag world: here, a narrator guides us through the everyday routines and antics rife within an army base.

As was the case with Sport Chumpions, Reid Kilpatrick returns to narrate (as opposed to the usual type casting of Robert C. Bruce.) He, too, channels the warm patronization dominates so many of the Tex Avery-Bruce collaborations. Even if the opening of “Attention: let’s join the army for a day and get a glimpse of military life!” does seem a bit unceremonious and brief—Freleng’s no nonsense, no fat chewing directorial sensibilities are felt in the short’s dawning moments, given that the viewer is immediately thrust into the action thereafter.

“For a day” very much means an entire day; audiences find themselves peering into a seemingly barren camp before daybreak. These rows and rows of tents against the vast, dawning sky communicate an intimacy in which the short is entirely reliant on.

These settings are not only for ambience, but for hitting a few gags along the way. Most notable is the synchronized snoring—tuned to “You're in the Army Now”, of course—from the soldiers within the tents. Ensuring the audience doesn’t grow bored on the sequence’s unflappable dependence on audio cues (so much so that a music score from Stalling is absent, forcing focus on the snoring and likewise legitimizing any intimacy in the atmosphere), a visual gag in which a tipi graces the foreground seeks to stir some interest. Executed in the rule of threes for further rhythm and coherency, no less.

A cross dissolve to the interior of the bugler’s tent—ever helpfully labeled as such—lingers on these snoring gags before officially starting the day. “Gags” being that his ears flap when he snores. It doesn’t exactly warrant the extended amount of time the camera lingers on him, but is nevertheless a coherent way to segue from one idea to the next.

Even buglers need buglers: an appropriately military themed cuckoo clock sparks a chain reaction of awakening. Cuckoo awakens bugler. Bugler awakens camp. Of course, to ensure that the reveille call of our human bugler is reliable and appropriately grandiose, worthy of rousing an entire camp, the clock’s own bugle call is tinny, muffled, and incredibly quiet. Not necessarily to the point where its muted sound is the punchline—moreso to distinguish this bugling hierarchy, of sorts. Such a purposefully poor sound quality reminds the audience that this is a novelty cuckoo clock and not a sentient bird character itching for some mischief. Kudos to Freleng for such meticulous attention to sound design.

This does result in a bit of a jump-cut—nothing major, but there could stand to be a few more poses of the bugler waking up after cutting away from the clock. Instead, jumping directly to him sitting up, wide awake and alert, makes the viewer feel as though they’ve missed something. Regardless as to whether or not there’s very much to miss.

Nevertheless, this all amounts to a punchline centered around modern conveniences: inserting a coin into a jukebox armed with a variety of bugle calls. Facticity in which the camera pans to reveal the jukebox is solid. A great example of the comedic frankness Freleng had such a grasp on; likewise with the continually casual manner in which the coin is inserted, reveille blares, and our human bugler retires back to bed.

A shot of all of the soldiers rushing out of the tents seeks to bridge a bit of a gap between ideas. That is, the short isn’t entirely gag after gag after gag—these moments of downtime, of innocuousness, of normalcy gives the hook of the short an authenticity. If the army was full of nothing but zany hijinks and gags with no room to breathe, the story (if one would be generous enough to call it a story) would feel disingenuous and insipid.

Instead, the closest alternative to a gag in this sequence is a straggler who finds himself emerging in his underwear. The love child of Elmer Fudd and Dopey Dwarf is quick to make amends.

Next, a dissolve to the soldiers marching in perfect synchronization. No narrator in sight—or, more accurately, sound—Freleng sticks to his guns in maintaining his desired ambience. His intended lighthearted atmosphere is still very much felt, but not to an overwhelming abundance in that it discredits anything the short is trying to achieve. As mentioned before, these comparative glimpses of stolidity render the cartoon more full, earned, and substantial, something beyond a string of gags deceptively wound into the guise of a story.

All of the above points apply to the reveal. Those assuming that the collective obedience to reveille so early in the morning is too good to be true are correct in their assumption. It’s a polite gag, but a logical outcome and strengthened through the aforementioned comedic restraint. The juxtaposition thrives, which strengthens the impact—serving as the inverse of how these gags usually go (soldiers appear to be marching in perfect synchronization, camera pans out to reveal their jelly legs and violent asynchrony) certainly strengthens the novelty.

“‘ten-TION!”

We never see the general—only hear his voice through the mouth of Mel Blanc. Obscuring his reveal gives him a greater sense of authority, both figuratively and literally; he serves as this enigmatic, almost omnipresent figure. It’s as though we’re too low on the ladder to even receive the privilege of looking at his face. After all, we are spectators. It’s a very subtle but clever decision that clearly constructs a palpable hierarchy that thereby strengthens the overall dynamic of the cartoon.

A pseudo domino effect ensues of the soldiers snapping awake. Whether consciously or inadvertently, the execution and general idea of this scene serves as a close extension to a very similar gag in Frank Tashlin’s Little Beau Porky, dating all the way back to 1936. Rather than all of the soldiers slacking off, Porky is the only one at inattention—his overcorrecting thusly results in a domino effect of soldiers toppling over like bowling pins. Tashlin takes his own gag further by reversing the footage as the general calls for attention; Freleng doesn’t quite reach that same level of abstraction here, but there certainly is no obligation to in the first place.

In fact, he prioritizes a more stolid means of delivery that saves a few bucks in the process. Rapid woodblock clopping personifies the action of the soldiers snapping to attention, therefore keeping that idea in mind when the camera cuts to the general observing in unguarded surprise. With these sound effects still in full force, aided with the jolts and flinches of the general as he reacts, the idea of the gag still lingers in a way that is concise and clear. The viewer doesn’t feel cheated when the camera cuts to a separate action that, on paper, seems to make a point to divorce itself. In other words, everything is still communicated clearly. Cutting to the general likewise reduces visual monotony induced by ogling at the soldiers for too long.

Gil Turner’s animation of the general is relatively easy to identify: the somewhat gelatinous movement, the constant fidgeting in hands, the comparatively small and often unanchored pupils. He even animates a particularly novel take that is as amusing as it is mildly confusing. Upon the final “TWANG!” sound effect, differentiating itself from the chorus of woodblocks and establishing a note of finality, bubble effects emanate from the general as he engages in one last major flinch. A particularly intriguing abstraction that really hasn’t been seen before; given how susceptible it can be to confusion, it’s understandable why it wouldn’t be used as often to indicate surprise. Certainly interesting nonetheless.

Thus, per the orders of the general, the soldiers sound off. Some of the designs are oddly specific in their chiseled, design features, starkly juxtaposed against the otherwise stock roundness of the accompanying soldiers. Not notable enough to instantly be pinged as a caricature of the staff (rest assured, that comes later), but certainly prominent enough to arouse suspicion.

Of course, a greater payoff lies at the end of the sequence outside of specificities in character design. Even if greater means “more obvious” in this context rather than “more funny”: a particularly dopey soldier struggles to remember what number he’s supposed to call out.

Blanc does what he can with the soldier’s deliveries. They certainly are convincingly cornpone, but that’s about the most that can be said—the gag, not being much of a gag at all, drags out for much too long and isn’t sustained through particularly innovative or intriguing character acting. While not terrible, its execution is similar to the sorts of gags so rife in the Ben Hardaway and Cal Dalton cartoons, where they feel like the equivalent of a long-winded joke that was never funny to begin with. This shares that same sentiment.

Thankfully, a smart quip from the general assures the audience that there’s more to this than numerological ineptitude. The general instead indulges in a pop-culture grab just featured in Robinson Crusoe, Jr.: “That’s right! Would you like to try for the $32 question?” Clearly, Take it or Leave It was a hot topic around the studio that week.

The joke could stand to end at that. Instead, Freleng and Dave Monahan drag it beyond necessity… but that too results in a bit of history. Rookie Revue has a pop culture pull relating to Take it or Leave It that Crusoe decided to leave: the echo of an audience member shouting “YOU’LL BE SOOOOO-RREEEEEEEEEEEE!” Fans of Chuck Jones will recognize that same pull in The Ducksters.

Our gag nevertheless reaches an unceremonious finish as the soldier declines. For as much energy and time was expended on such a long-winded tangent, a fade to black would at least offer the illusion of security and finality.

Instead, a jump cut to yet another bugler (in spite of our first candidate clearly implied to be the only one in camp, hence the proud branding on his tent) calls the troops for lunch... ignoring that Bugler #1 called for reveille just minutes ago. A fade to black would likewise offer a semblance of security to a rather loose and meandering “gag”.

Our assigned mess hall bugler is cast not only to cushion the implication of our first bugler sleeping on the job, but, likewise, is cast for the benefit of his girth. His giant barrel chest certainly comes in handy as Freleng treads one of the oldest jokes in the book that was once a staple in the Harman and Ising days: a character deflating into nothingness as they blow into a horn.

Design sensibilities and craftsmanship has changed drastically in the past 10 years or so from Harman and Ising’s reign. Thus, the comedic discrepancy between the “sophistication” of his design and the absurdity of the visual reaps its own benefits. Such is most notable through the manner in which his uniform begins to devour him. It’s a reminder of what once was—a permanence that isn’t exactly present in the same gag during the H-I days. Allowing the soldier to march away in pompous disregard, clearly unbothered by his shrunken state, likewise seems like a more contemporary twist on such an oldie—most instances would focus the camera on one final static pose before moving on. No exit or any other additional acting. Barely any acknowledgment.

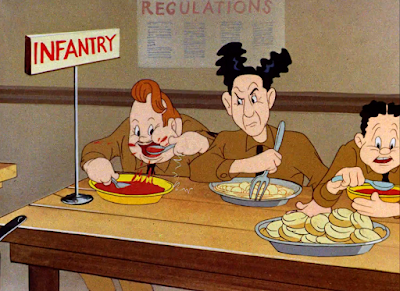

Moving on, heralding of the mess hall logically offers mess hall related gags. Dick Bickenbach’s hand is noticeable in the first tangent of the soldiers stuffing their faces, whether that be the result of the deft, varied timing in their movements or the drawn exclamation lines when one of the soldiers notes the audience.

Of course, for those watching this cartoon be screened in the Warner studio, the biggest takeaway are the designs of the two leftmost soldiers. Caricatures of Tex Avery and Henry Binder, now exceedingly conscious of their company, gorge themselves with the utmost daintiness and primness. A palpable change in Stalling’s musical orchestrations—discordant, heavy, abrasive when arriving to the scene, flighty and juvenile upon the audience awareness—really solidifies the parallels and makes them memorable. Even if it is for just a short clip.

More eating gags thereby follow: each division, handily labeled through the convenience of a sign proudly at the end of their tables, consumes their food relating to their jobs. That is, the machine gunners shovel beans in their mouth with rapid ferocity; their breaks to chew are synonymous to their implied real life counterparts giving the guns time to cool down. Rapid machine gun sound effects from Treg Brown clinch the metaphor beyond a lame gag.

Bombers, on the other hand, throw their nondescript foodstuffs into their mouths with perfect precision. Pacing on this gag is a bit more awkward than others; not by much, but the fixation on the vacant chewing that occurs after seems relatively arbitrary.

And, finally, the suicide squad sentenced to a lifetime of hash. Note that each of the soldiers are drawn with long faces—a clever obligation to the age old idiom.

Our narrator has somewhat surprisingly remained relatively absent throughout the cartoon. This isn’t exactly a critique, seeing as the various segments largely speak for themselves—to shoehorn an unnecessary commentary out of sheer obligation does no favors across the board. Instead, Kilpatrick’s orations are utilized when necessary. Often when Freleng needs a more tangible means of transition, a clear segue between ideas.

As is the case now, where the next bout of comedic focus lies on a cavalry. Horses were still utilized by the army at the time of this short’s release—perhaps surprisingly, given how antiquated a cavalry feels against WWII’s barrage of innovative artillery and machinery and aircrafts. January 1942 would mark the last American cavalry charge, executed by The 26th Cavalry Regiment in Morong—only three months after this cartoon’s release.

Focus on the cavalry nevertheless results in a rather tame gag: the horses marching in perfect synchronization. It seems to beg a stronger reaction or sense of exaggeration that remains absence; instead, its stolidity doesn’t do it much favors. Perhaps that stems from an unconscious comparison to other horse gags in other shorts preceding this one. It does prove difficult to argue with the horse conga-line in Meet John Doughboy. Nevertheless, it feels as though Freleng could have done more with the gag than what is actually realized.

“The infantry is the backbone of the army. Marching mile after mile is a matter of routine for these hearty foot soldiers.”

Cleverly (and economically), Freleng demonstrates this “mile after mile” trek through a sweeping camera pan of the valley. Obscuring the soldiers not only saves a few bucks and a few sweeps of the hand, but enforces an illusion of grandeur—the hike must be long if even we can’t see them physically marching. Strategically placed tan blobs on the winding roads indicate the presence of the soldiers instead; the distance is far enough that their imprisonment in the painting and lack of movement can be chalked up to the perspective. Motion from the camera pan likewise disguised any suspicion. The twists and turns and elevation of the mountains are a much larger priority in informing the audience of the distance than the actual animation itself.

Stalling’s musical orchestrations adopt a laden, lugubrious tone to accentuate the weariness of the soldiers and their trek as they are insulted through an increasingly common tagline in golden age cartoons. Having them actually turn their heads to the billboard(as opposed to walking past) bestows further importance and even longing; they’re forced to confront the luxurious alternative that will forever be out of reach.

“Following close behind: the camouflage troops!”

Accompanying visual speaks for itself. Inclusion of the horseshoes reminds the viewers of the cavalry, reminding them that the earlier horse-themed gags were not for naught. Likewise, painted elements in the foreground introduce a depth and dimension to the environments that solidifies that yes, the soldiers are really transparent and are truly interacting with their environments.

Next, a somewhat more tonally grandiose segment dedicated to the experimentation of a new “gun”, as the narrator so colloquially labels it. Dot eyes on the soldiers are equally intriguing as they are somewhat confusing—there is a vast stylistic clash between the realism and the cannon and the lack of definition in the troops, but that seems just as purposeful. Grandeur of the flashy new cannon is exaggerated all the more in comparison.

Which is perfect for the resulting punchline, who revels in its lameness: a cork unleashed with a violent anticlimax. Meet John Doughboy features the very same gag with a similar set-up, and both are fine in their own right—Freleng’s additional milking of the climax with the narration, the anticipatory music sting, and shuddering antic on the cannon certainly earn additional points nevertheless.

“In contrast to the mechanized equipment used by the soldiers of today…” Kilpatrick’s narration is outfitted atop a visually striking pan of the equipment in question. There is a striking amount of detail regarding the atmospheric perspective and color temperature in the painting, as the tanks nearing the background are doused in a faint blue hue. Such gives the layout a grander sense of scale, accentuating how large and how many tanks there are. Undoubtedly, Freleng is reliant on these crawling background pans throughout the short—such meticulousness and attention to detail in the coloring and perspective nevertheless makes the most of it.

That again reaps its own benefit of incongruity: such grand and artistically inclined background paintings are used as a buffer against purposefully mundane and lame visual gags that follow thereafter. Such as the makeshift machine gun, as exemplified through Kilpatrick’s ramblings of the makeshift substitutes utilized by earlier conscriptees. Kilpatrick himself serves double duty by voicing the gunner’s “Bang! Bang!”s, executed with proud nonchalance.

This directorial tangent offers a bit of variety to the structure of the cartoon: the camera cuts from idea to idea, a metaphorical ellipses separating each gag but strung together under the same symbolic sentence. It’s an efficient way to knock out a few gags without the threat or confusion of figuring out how to string them together coherently.

Makeshift tanks are, of course, not tanks at all, but obtrusively labeled as such for clarity. The biggest takeaway stems from the Good Rumor truck; its tinkling music score as the camera sweeps past gathers the most attention. This, too, is yet another continuation of Good Rumor references in Warner cartoons, largely implemented thanks to the availability of its real life counterpart stopping in front of the studio and often feeding a swarth of hungry animators. It’s an indulgence that probably got more laughs at the studio screening than theatrical viewers, but the sheer juxtaposition is enough to expand its audience to all. Another reliance on a horizontal background pan.

A parachute sans parachute is actually a gag within a gag. Not only is it following Kilpatrick’s reigning theme of flimsy substitutes—it’s actually a mirror to real life. With the sudden onslaught of war in 1939, the need to expand the military predictably prompted shortages in materials and supplies. Thus, looping entirely back to the main idea of the sequence here and its own substitutions amidst said shortages.

With this final tangent ruminating in its aerial theming, Freleng maintains that theme by following with yet another plane-centric gag: planes playing tic-tac-toe in the sky.

It very much feels like a leftover from Tex Avery’s Aviation Vacation. Contrast is helpful in bolstering its comedic value, as the comparatively “professional” shot of the shiny, rendered planes flying in formation sets a precedent that is violently disregarded through the actual outcome. Still, the sequence probably doesn’t need to linger as long as it does for the audience to get the point.

Another similar tangent: target practice. Freleng abides by the same structure of cushioning a purposefully juvenile punchline with a stolid, visually grandiose introduction. Playful juxtaposition of the reveal is a bit stronger thanks to the adherence to the carnival theming (particularly aided through Stalling’s orchestrations of “The Sidewalk Serenade”). Yet, like most aspects of the cartoon, similar takes on the same gag are better executed elsewhere.

Moving forward, we now reach the ending climax of our cartoon—which, coincidentally, coincides with one of the most memorable visuals in the cartoon. Or, perhaps, memorable regarding what it would lead to, inadvertently or otherwise: the extensively long barrel of a cannon, costing an incredibly long camera pan, would best be remembered in Tex Avery’s Blitz Wolf the following year. Avery’s example of the gag is much more grandiose and taxing of the audience’s nerves—all typical attributes of Avery’s directing. That isn’t to posit that he stole the visual from this cartoon, but it is worth mentioning the similarities if only for sheer novelty.

Kilpatrick mentions that the directions for firing these “huge monsters” originate from Army headquarters. Thus, the short’s remaining minutes fixate on the laborious, tense, melodramatic preparations that go into firing such a dangerous and colossal weapon.

Reaching the climax does dip into a pattern of repetition, but one that feels comparatively earned in its suspense. A general calls out instructions to his crew (note the “Harris Co.” printed on the map in the background—a nod to frequently caricatured animator Ken Harris), which are parroted through a series of cuts. The cartoon then delves into a pattern: general, broadcaster, broadcaster and man manning the cannon. Cuts grow quicker and more abbreviated as the action climaxes, instructions shorter and more terse. To deny its monotony would be disingenuous, but it is certainly understandable why Freleng does what he does. Quickening, climaxing cuts portray a sense of anticipation, of danger, of overall dynamism. Such adherence to the same general idea likewise juxtaposes against the overall pacing of the short, mainly comprised of isolated incidents. Such directorial dedication in this moment really sets it apart as something different and something worth paying attention to.

“Fire!” (x3)

The cannon obeys… segueing into a somewhat awkward shot of the bullet flying. Or, more accurately, no bullet at all. Between the adjacent shot of the cannon firing and the sound of the projectile whistling through the air, the audience is obviously able to piece the action together. Regardless, Freleng communicates this by fixating on an empty background of the sky with no animation; the implication is that the missile is above the camera frame, but the maneuver unfortunately reads as lazily as it actually is. Between all of these long pans and static shots, it feels as though his unit was strapped for either time or money. Maybe both.

Clarity or lack of clarity, the ending punchline nevertheless communicates, which is arguably the most important objective. The general’s headquarters is promptly blown to smithereens. From a cartooning (and animation historian) perspective, the punchline can be seen a mile away: how else would all of this laborious preparation result? Even then, Freleng does a fine job of still embracing the surprise of the reveal. To the audience, the gag is more shocking—the strenuous buildup leading to this aggressively ironic anti climax is a strong buffer.

With a comedically obtuse black eye to accentuate the impact of the missile, the general’s parting words channel the wisdom of one Lou Costello… with the necessary contextual changes: “I’m a baaaad general.”

Though stated just paragraphs ago, this observation is worth reiterating: Freleng clearly seemed strapped for resources on this one. Looking at his filmography and realizing that his next short is Rhapsody in Rivets—the Oscar nominated Rhapsody in Rivets—contextualizes the condition of this cartoon much more. It doesn’t incorrect to surmise that this short was shunted to the back burner in accommodating Rivets’ priorities; it certainly would justify why the short is the way it is.

For the record, it isn’t a completely terrible short, or even truly bad. It’s yet another case of antagonistic mediocrity—at least with a stinker, there’s something to say about it. This short is a big heaping dose of nothing, which is better than being a complete bomb of a cartoon… but less interesting all the same.

It is a more structurally sound cartoon than Sport Chumpions, at the very least, and one can feel Freleng growing more accustomed to the spot gag formula. His attempts to vary the short’s pacing—holding off the narration in some points, engaging in a rapid slew of ideas in others, lingering for the climax to distinguish it from the short’s body—are very much felt and appreciated.

Regardless, it just isn’t a very interesting cartoon. Gags range from pitifully lame (if not often confusing) to mildly chuckle inducing. The reliance on long, rolling pans and repetitive maneuvers is felt, some shots flow into each other more smoothly than others (with hiccups being particularly concentrated in the beginning half), and there’s an overall brusqueness in tone that supports the short’s overall unremarkability. It’s another drop in the bucket, but a drop nevertheless.

.gif)

.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment