Release Date: January 4th, 1941

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Chuck Jones

Story: Rich Hogan

Animation: Rudy Larriva

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Bugs), Arthur Q. Bryan (Elmer)

A new year rife with possibilities, 1941 marks some notable shifts in the tide. One of the most notable being the departure of Tex Avery—he would take his leave in July that year, briefly floating around at Paramount before settling down at MGM, where the trajectory of his career would be forever changed. More will be elaborated on the conditions of his leave in another review; for now, it’s only important to know that Bob Clampett was able to inherit Avery’s old unit, gaining him access to superstar animators such as Bob McKimson and Rod Scribner. A decision that, likewise, would forever change the trajectory of Clampett’s career.

That open unit left by Clampett was to be inherited by Norm McCabe, who, as mentioned in our review of The Timid Toreador, dabbled in some co-directing to help a Clampett out on sick leave. McCabe’s unit was dissolved in late 1942 when he left to join the army, making his stint one that is relatively short but nevertheless worth mentioning.

Looming impacts of the war are also worth mentioning. Propaganda cartoons were still a slight ways from exploding on-screen, but nods to the war would become more apparent through various gags. While its impact on the shorts will likewise be analyzed at another time, it is worth noting that the wild, brash, hysterical attitudes adopted by the cartoons, a prevalence on wanting to see the good guy beat the bad guy, wanting to be intoxicated by fervor and pride and confidence exuded by the cartoons, is indeed a product of the war’s influence. Unfortunate as the circumstances may be, many of the best cartoons ever put out by the studio lie within this period.

In any case, it becomes all too available a compulsion to get ahead of ourselves with such retrospectives. For now, we focus on January 1941. Or, more realistically, October 1940, when it was announced by the Film Daily that this short was being rushed through production. Indeed, A Wild Hare was a major hit, and both Leon Schlesinger and the public wanted to see more of the rabbit.

And, as of this cartoon, he finally has a name. The name Bugs, as previous reviews have expanded upon, has been in use since at least 1939, popping up on model sheets and promotional material within the studio. The public, however, only knew him as the rabbit. To include a title card triumphantly introducing the rabbit’s name in big letters, trumpet fanfare underscoring its inclusion, lax pose from Bugs indicating a proud yet contented awareness is a big deal.

Then again, Blabbermouse also got his own title card in Shop, Look and Listen—perhaps some of the mystification with Bugs’ scenario stems from the hindsight of knowing that his popularity would stick. This is only the beginning.

Outfitted with the yellow gloves left behind by his predecessor in Hare-um Scare-um, the change would only last for this cartoon. Likewise with his Jimmy Stewart inspired voice. Given that this short was a direct response to A Wild Hare, the decision to model his voice after Stewart’s wasn’t a product of aimlessness or confusion—rather, a purposeful decision by Jones to differentiate his Bugs from Avery’s. While thankfully the voice would also confine itself to this cartoon only, Blanc does make it work within the context of this short. It’s an endearing self indulgence from Jones, if one could label it as such, that succeeds in making this cartoon unique.

As for the story itself, the title is self explanatory; an oblivious Fudd adopts a certain rabbit posing coyly in the pet store window—and quickly learns to regret the decision.

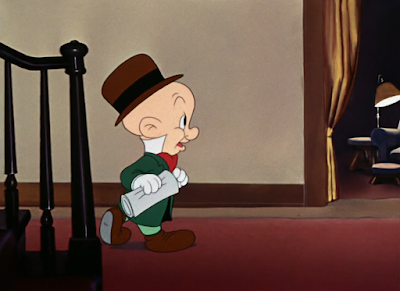

A very low key song number eases us into the pace of the cartoon: “Fountain in the Park,” as sung by one Elmer Fudd. It fittingly accompanies his own stwolling strolling downtown, which is atmospherically depicted through an intimate low angle. Such places the viewer’s eye level closer to the street, giving a spotlight to various stains, puddles, and other markings on the ground—thus, the environments feel more lived in, believable, whole.

It likewise makes Elmer seem even more short and squat than he already is. Ironic, given that the sidewalk seems to boost him in height; in spite of that boost, the camera is still able to capture much of his body and have his actions read clearly. Such renders him affectionately dweebish.

The pan is smooth, the music is nice, the atmosphere is felt; it’s a refreshing, conscious burst of cinematography. Perhaps the greatest beat of all stems from the breathless recitation of the lyric “I was taken by suh-pwise…!”—that coincides with Elmer’s sudden halt in front of a store selling lingerie, very clearly labeled through bold signage.

Coming to a physical halt draws enough attention to it, both the walk cycle and camera pan stopping in their tracks, but the addendum of the music coming to a bated halt as well really embraces the suddenness of the gag. Elmer’s suh-pwise therefore has more credibility. Staging likewise is commendably concise; his body forms a clear frame around the sign, guiding the audience’s eye, as well as the colors painted in red to bestow a bawdy urgency upon the advertisement. It’s a great character beat that is a genuinely funny—and risqué—gag that all unfolds very smoothly.

Worth noting, animator Bobe Cannon receives a shoutout in the pet store window—Elmer’s impromptu destination.

Rather than cutting directly to his staring at the window, the momentum of the rolling pan is sustained by having the camera move upward. It connects the flow of ideas well, maintaining the established rhythm (furthered through a piano glissando accompanying the camera movement) , and allows for the cut that follows to possess a bit more impact in its reveal through the established clarity. That way, the audience can focus on what caught Elmer’s eye—not where he is or what he’s doing.

Said attention-grabber is a certain little gray rabbit. Already, Bugs’ introduction is hilarious; a rabbit in a pet store makes sense. An anthropomorphized rabbit that is somewhat more akin to a human through his two-legged stance, cognizant coyness and awareness as he makes direct eye contact, and the ridiculousness of his garish yellow gloves are another. All very far removed from a domesticated rabbit. So, that Elmer doesn’t seem to take notice of this or even think beyond the surface level is a great comedic gift—it leads to Bugs’ eventual adoption and the mayhem that soon ensues.

First, however, a series of signs in the window display entice our oblivious customer. Carl Stalling uses a backing accompaniment of “Angel in Disguise”, which is a major first—originating from the 1940 film It All Came True with Humphrey Bogart and Ann Sheridan, it would become the newest addition in Stalling’s rotating tool belt of favorite backing tracks. Here, it both represents a bit of an ego for Bugs (the title of the song and his acting—which is expertly animated through somewhat disingenuous eye blinks, head bowing, shoulder swaying movements—both indicating that he could be the “angel” in question) as well as foreshadow that there is more beyond his cute, cuddly surface.

One of the sign gags being a major price reduction alludes to this as well; nobody slashes a cost of $150 down to 98¢ without some sort of backstory or reason. Who’s to say how many people were in Elmer’s same situation with the rabbit before he came along.

The entirety of the adoption process is portrayed off-screen. Its execution and tone is a method that Jones would adopt and refine in his later cartoons, with a pair of comparatively burly hands yanking Bugs out in a flash being particularly reminiscent of his later work. An appropriately timed pause allows the viewers to fill in the blanks, so that Elmer’s emergence from the store with a box isn’t too sudden or confusing. Very clear intentions and sequence all executed without a line of dialogue.

Some more celebratory singing is in order—singing that Bugs himself participates in. Jones would reprise this “impromptu duet” to a somewhat grander scale in the opening of My Favorite Duck. Bugs’ incomprehensible warbling benefits from his Stewart inspired vocal stylings, as even in shorts where he barges in to sing a duet in an attempt to be obnoxious (such as this scene from The Wacky Wabbit), Blanc’s vocals are so rife with charisma that it’s difficult to be thoroughly annoyed. Here, he sounds utterly ridiculous. It makes Elmer’s blatant inattention all the more hilarious.

Animation on Bugs himself is a little awkward; front facing angles seem a bit congested and smushed, floaty, but it’s completely understandable given that it’s the first time the Jones unit has handled the rabbit under his new redesign. It’s likely that Rudy Larriva handled the animation, as it is particularly reminiscent of Bob McKimson’s work; heads tilting in intricate angles, a general solidity in construction (even with all of the occasional awkwardness of Bugs and Larriva's slower timing/spacing) and very subtle intricacies in the acting: Elmer tilting his head, flicking his eyes up in contemplation after Bugs taps on his shoulder is a brilliant detail.

Smacking sounds exude from Bugs’ taps on the shoulder, which is an amusing piece of sound design. It manages to fit well into the action, and it indicates a sort of aggression and overzealousness that melds well with Bugs’ attitude in the cartoon.

“Whatcha got in the box, doc?” The second uttering of “doc” in a Bugs cartoon seems to cement its permanence with the character.

Thus, the two launch into a routine that, even by Bugs’ second “official” cartoon, isn’t new. After all, it was Jones who implemented the dynamic with Elmer’s Candid Camera—A Wild Hare borrows many beats from the cartoon itself. First, it was Bugs asking what Elmer was taking a picture of. Then, Bugs asked about what he was looking for digging in the ground. Now, he asks about what’s in the box. And, as was the case in the aforementioned examples, Elmer takes the bait and converses with his adversary-to-be.

Granted, there is a bit of a twist; rather than him coming to a sudden realization, allowing Bugs to retort with some snide comment, it’s Bugs who continues to be the provocateur. In fact, Elmer never shows any sort of indication of surprise, horror, or even befuddlement. It preserves the sympathy the audience has for the character—rest assured, he will get angry, but it climaxes over time rather than explodes immediately. While it does contribute to some of the bloating in the cartoon’s pacing (which isn’t egregious—just a fact of life with Jones’ shorts of the time), it likewise keeps the audience engaged in the conflict and curious to see how Elmer react or if he will react.

Bugs’ retorts are more in the wheelhouse of his outbursts in Candid Camera. That is, all seems fine and dandy and amicable before a burst of ego prompts him to chastise Elmer. The viewer gets the sense that his complaints aren’t completely sincere—just a means to screw with his adversary—but they’re acerbic enough to arouse pity when Elmer gawks aimlessly at the camera.

Moving forward, a fade out and back in heralds a complicated pan overtop Elmer’s house. A brief beat allows the camera to rest on his labeled mailbox, enabling the audience to contextualize the location—it likewise is just a smart piece of establishment that creates a nice juxtaposition with the flow of the camera movement. The pan seems to ease along more naturally with that little pause beforehand than it would if it began moving right at the top.

Granted, there are some issues sprinkled within; the camera seems to jitter as it approaches the change in direction, and Elmer’s back porch is way off in perspective, almost rendering it a flat object instead of a building occupying space. Regardless, both are forgiven through the complexity of the angle and pan. All that matters is that Elmer rabbit pen (or, more realistically, a dog house inside a chicken wire fence) reads clearly and informs the audience of his endeavors.

Bugs’ visibly disgruntled expression from within the box is priceless. Whereas Avery’s rabbit might be contentedly smug, comfortable with his fate as he knows he’ll find a way to weasel out of it, Jones’ Bugs is conceited and prideful. Being cooped into such a pen is a big insult to him. It’s a somewhat more elaborate extension of the prototypal Bugs Jones used in Candid Camera, only easier to take seriously. Slightly.

Ken Harris animates a gorgeous and memorable portion of the cartoon: Bugs “adapting” to his new home and eating his dinner. Acting has subtlety and nuance (for example, Bugs can be seen mouthing something when Elmer lowers him into the pen—likely curses), motions possess real weight and tension, and in general is full of life and solidity. Poses are differentiated for maximum comedic effect—Bugs’ ranting is broad with lots of vast gestures, where as more subtle japes (“…It stinks!”) are maintained through held poses and get laughs through their comparative rigidity.

Staging is essential to the scene as well. An overlay of chicken wire bestows credibility to Bugs’ dissatisfaction by appearing to close him in; it’s claustrophobic, intended to be distracted. With the viewer looking in from the outside, it’s as though they’re viewing a zoo exhibition. All aspects unkind to Bugs’ ego, which he enunciates in his angry, grumbling rant.

Another clever staging decision is the suddenness of his “dinnew”, as declared by one Fudd. The camera tracks Bugs’ pacing, so that when he returns to his starting point, he’s confronted with a fresh tin of vegetables. No hook-up pose, no sound effects off-screen providing any indication. Intended abruptness is much stronger thanks these aspects, and the momentum and pacing is likewise more clear and cohesive without a series of cuts. Bugs’ surprised “What’s this?” holds more credibility with the sudden inclusion in mind.

Harris’ animation is especially strong in Bugs eating his dinner, perfectly complimenting Blanc’s hilarious, visceral line reads. As he stuffs his face, Bugs quite literally chews out his new owner on the asininity of the food (“Whaddaya think I am? A rabbit!?”) and guilting him on how “terrible” it is—all while stuffing his face. His anger and ferocity is perfectly encapsulated, eating giant chunks of vegetables seeming like a genuine hurdle. Blanc’s line reads transcend the awkwardness of Bugs’ voice patterns and are proudly emotional.

A great acting detail, Bugs even dedicates a beat to picking out something from his teeth. Such a discriminating little piece of personality that further accentuates his sentience and ego.

Bugs’ ranting never comes to an end, which is a great gift to the viewing pleasure of the audience. Rather, a fade to black is its own signifier of polite abandonment.

Likewise with the fade in to reveal the empty food tin. Sans half eaten carrot, of course; in a way, displaying a remnant of what once was—in this case, the food—makes the tin seem even more empty if there were no leftovers at all.

Likewise with Bugs’ bloated stomach. Jones allowing the visual cues to read for themselves almost seems Freleng-esque, in a way—there’s an affectionate dry irony in the filmmaking that is comparable to Freleng’s own love of wit and contradiction. Contradiction continues to manifest into Bugs’ verbiage.

“Look at him stuffing his great big face while cold little rabbits lie out here starving!” The bulge on his stomach seems to insist otherwise.

A pan to Elmer’s house is much more smooth in motion and clarity than the initial diagonal birds eye view. Namely, that’s because the pan itself is painted with the shift in motion in mind. The camera itself is on a horizontal track, but the hedges arc and dip in a way that suggests a diagonal turn. Likewise with the slant of the house. It’s a complicated maneuver that looks great in motion—one that required lots of planning. The window framing Elmer is another great touch, as is the angle of him towering over the audience. A power imbalance—if one could consider Elmer a figure of power—is thusly established by having Elmer be raised up high, indicating importance, and Bugs left to stew down on the ground.

“That was weawwy awfuwwy good weg of wamb,” is another amusing nod to Elmer’s cushy life, further justifying Bugs’ disgruntlement. Leg of lamb is a delicacy, a commitment, a signature of well-of living. Elmer’s complete obliviousness as to how well off he really is could add even further insult to injury. Bugs is keenly aware of his injustice (fabricated as some of it may be), while Elmer thrives in his blissfully oblivious utopia.

While the pacing of Elmer settling in for the evening suffers from typical Jones-ian bloatedness, it’s somewhat necessary in establishing a contrast between Bugs’ brashness and Elmer’s cushiness. Turning on the radio, sitting in front of a fire, reading the newspaper comics (including the first allusion to Dick Twacy—er, Tracy—in a Warner cartoon!) are all further arguments for his life of luxury. Same with the slowness of his movements and settling down—he can afford to take his time. He’s in no rush. Worth mentioning are the warm colors that predominately make up the scheme of his living room; Creams and oranges and reds render the dark blues and greens of the outside seem even more cold and empty.

An odd plot contrivance occurs with Bugs barging into the home. More specifically, he bursts into Elmer’s living room and wastes no time turning on light switches, radios, grabbing the newspaper to only throw it back in the chair again, and so on. That in itself is fine. It succinctly conveys that Bugs is here to be disruptive and skew things out of order, and the action itself unfolds very smoothly, all in one, long, continuous pan. Regardless, it requires a stretch of the imagination considering the radio and lights were just on seconds prior. It seems pretty hard to believe that Elmer would go through the trouble to turn all of that off just to answer the door. Not because he’s entitled to it—rather, the thought probably wouldn’t cross his mind.

In any case, his entry does prompt a rather entertaining dance sequence between the two. As was the case in Bedtime for Sniffles, Phil Monroe is the designated dance animator—their altercation isn’t nearly as elaborate as Sniffles’ own little ballet, but it serves the need to put a focus on some musicality and again convey how much of a pest Bugs is being. Elmer doesn’t seem the type who’s itching to dance with a partner.

Most of the dance does just consist of them moving back and forth within the plane, which could stand to be cut short a few seconds. Still, Monroe’s draftsmanship bestows a lot of appeal and cute charm to both characters. They’re attractive to look at, and the movement is serviceable—the only two things you can really ask for.

Tex Avery’s influence can be felt through an intimate close-up between the two: Bugs’ “You dance divinely… rah-lly, you do,” channels the likes of Katherine Hepburn. Who, as we all know, was the apple of Avery’s comedic eye.

A dissolve to Bugs being thrown rather violently into his pen is incredibly well executed; Treg Brown’s audible smacking effects as he rolls to a stop effectively embraces the ferocity of the throw, which is vital in portraying Elmer’s annoyance. Likewise, it aids in wounding Bugs’ pride further—the louder, the more vulnerable, and the more vulnerable, the more embarrassing.

A steely “Okay. So I got thrown out. I suppose none of you’ve ever gotten thrown out of no place!” properly confirms that Bugs is indeed offended. It’s an endearing break of the fourth wall through its comparative nonchalance; there’s a organicism to it, with Bugs only sparing a side-eye to the audience. The filmmaking doesn’t make a big deal about how he’s talking to the audience; a habit Elmer’s Candid Camera could take up occasionally. Natural, haughty, and dismissive.

Jones heralds in some more bloated shots of domesticity, but they are again not bloated without reason. Intricacies on different forms of lighting are a particular focus—the landing of the upstairs is shrouded in darkness, light pouring only from downstairs, until a flick of a switch off-screen reverses the two. It seems that Good Night, Elmer was effective lighting practice, as one can feel Jones pulling his experience from more atmospheric cartoons such as that to apply whenever he can here. Pacing can falter, of course, but for the most part he straddles an effective line between atmospheric and comedic.

Furthermore, any lugubriousness present is helpful in establishing further juxtaposition between Bugs and Elmer. Bugs dashing up the stairs and into the guest bedroom is much more reckless, energetic, and brash than Elmer’s contented ambling in his quest to put on a bathrobe. Suddenness of Bugs’ introduction is also very effective—again, no shots of him sneaking out of his pen, knocking on the door, breaking into the house. The audience of course braces for more antics between the two, as there would be no cartoon otherwise, but his entry is still sudden enough to be surprising and funny.

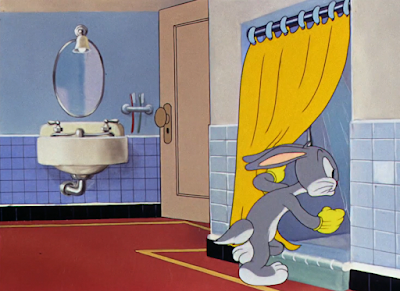

Especially since it results in Bugs kicking Elmer out of his own bathroom. Pet Rabbit is somewhat enigmatic in that it flaunts a few instances of comparatively “promiscuous” humor—at least, promiscuous against the prevailing innocence of Jones’ shorts thus far. In other words, bathroom humor wasn’t often a go-to for him. Here it does work because it’s so surprising and proudly ridiculous; Bugs’ magazine (“SEE” being a parody of Look Magazine) indicates he’s going to be in there awhile. Same with his haughty “Please wait your turn!”, indicating that there will be some waiting involved.

A climactic reaction shot of Elmer is again on the slow side, but appealing in its drawings. A drumroll underscore gives visibility to the tension, caricaturing a slow broil of emotions. Its eventual eruption—which manifests in Elmer bursting through the door—is made all the more satisfying through such a stark contrast, even if it takes longer than necessary to get to that point.

Jones keeps the innuendos going through a great little detail that’s easily missed; a cut inside reveals Bugs to be in the shower instead, subverting the expectations of the audience (much to the relief of the censors). However, Elmer charges straight forward, running offscreen. Such implies that he immediately ran to wherever the offscreen toilet would be (which is not in the bathroom at all; again, too scandalous for the censors) and ready to yank Bugs off of it himself.

Instead, there’s a slight beat as he has to reroute, turning around in the other direction to march right into the shower.

Elmer showering with his robe on is an obvious cheat—given his role as a human, seeing him naked would be a bit more disconcerting (and the fact that he’s Elmer Fudd is another justification), and would possibly lead to more protests from the censors.

However, it is also very important in maintaining the rhythm of a brief back and forth between he and Bugs. He marches into the shower, throws Bugs out. Bugs marches in, gets thrown out in the exact same manner. Both have the same timing, same coherency, same rhythm—stopping to demonstrate Elmer undressing, even if in passing as he marches or just to place it on a hook outside the shower, would lose the impact of the symmetry. Its execution thrives on its matter of factness, its boldness. It conveys a no nonsense attitude from Elmer that’s pivotal in justifying Bugs’ disgruntled ranting in the coming scene.

Said ranting is a great bit of character acting. Stalling’s circuitous, meandering accompaniment of “Angel in Disguise” is effectively defeated yet conniving, broiling—it provides the perfect mirror to Bugs’ sulking (flicking his finger in the water with conceited malice). Difference in color regarding the parts of his body that are submerged are believable and striking, especially with the benefit of the cartoon being recently restored.

“A rabbit can take just so much of this…” Laden and motivated, Bugs’ footsteps are tactile in their weight and establish a nice rhythm that fits the meandering tune in the background.

Jones’ encourages an informal invulnerability by demonstrating Bugs’ thought process unfold all on screen. Perhaps this note stems from hindsight, knowing how Jones’ rabbit in later years would barely have to lift a finger to solve his woes. Regardless, there’s a sort of sympathy and intimacy that is spawned from watching Bugs hatch an idea in the moment. It comes as a sudden halt—ears perking, eyes widening. A very well animated piece of character acting that communicates a lot. Bugs’ may be a crotchety, conceited pest in this cartoon, but Jones still succeeds in making him likable. Likewise, Elmer isn’t entirely the bad old antagonist who we should feel disdain for. There’s a great balance with both characters that keeps the audience invested in their respective motives.

Here, Bugs’ next course of action is to fake his drowning. Animation teeters on the more leisurely side—could stand to be faster and more exaggerated given Bugs’ (feigned) hysteria. Yet, in the same breath, it accents the disingenuousness of his endeavors. Of course he’s not truly frantic or concerned. Not if he’s throwing his voice to declare “Man overboard!”

Elmer’s reaction is delayed, but he does react. Jones attempts to make the robe cheat seem more convincing by having Elmer put his arm through the sleeve as he runs, implying he was undressed; it all happens too conveniently and quickly to be convincing, but the effort is appreciated. Likewise with his dutifulness to slap the bowler hat on his head, as though he can’t be seen without it.

An overhead shot of Bugs’ “body” could be another cheat in itself. Only having bubbles emit from his unmoving mouth saves lots of time and money; a necessity if this was rushed for time. Realistically, the stillness is for effect—no ambient movement of any kind cements the notion that something is seriously wrong… even if there’s no way Bugs would ever be able to drown in such a puddle of bath water.

Sure enough, the third Bugs and Elmer routine engages in their third fake-out death. Jones draws inspiration from his previous outing with the pair, Candid Camera, as it involved Bugs saving a drowned Elmer in the midst of a mental break. Nuances established in A Wild Hare eke their way into this routine—Bugs repeatedly opening one eye is particularly reminiscent to his wide, goofy grin in the former realizing he’s successfully tricked his adversary.

Here, the performance is much more open in its disingenuousness, particularly through Stalling’s whiny, weepy score of “Old Pal”. It doesn’t hold a candle to the intricacy of Wild Hare’s fake-out, but that’s not entirely on Jones’ behalf—what does? It does seem more like an obligation, a sort of unspoken formula that needs to happen in every Elmer and Bugs cartoon rather than a genuine, driven piece of character acting. Regardless, the audience feels sympathy for Elmer, and Bugs’ awareness is endearing.

The resolution arrives much quicker here than it does in both of its successors; Bugs immediately hops to his feet, declares Elmer his hero, and kisses him on the cheek. No slow burn, no time for Elmer or the audience to process what just happened. Bugs is a bit of a loose cannon in this short in that he seems to operate on unprovoked extremes—one second he’s ranting and raving about his quality of life, next second he’s affable and getting Elmer to dance with him. It’s a sort of impulsive fluctuation that’s much more akin to Daffy—especially early on—than it is Bugs, but manages to work given that it feeds into his trickster attitude. It’s as though he’s even faking out the audience by going from one extreme to the other, keeping him enigmatic.

Such is proven through a close-up of Bugs getting personal with the audience. His “How d’ya like this guy? He saves my life,” is delivered so objectively that it feels like he’s even punking the audience. The retort is wholly facetious, but the confidence in his delivery is very convincing. Interestingly, it seems to have used a similar, less charismatic close-up from Candid Camera as an animation reference.

Role reversals between cartoons continue. Instead of Bugs kicking Elmer in the rear, as he does in both Camera and Hare, he implores Elmer to give him the same treatment as means of a truce. That Elmer initially refuses says a lot about his character: he’s an impressionable old sap.

That manifests into the eventual kick itself, which is executed beautifully. No impact of any kind. Elmer’s foot barely makes contact. In fact, Brown’s adjoining sound effect almost sounds too violent in comparison, creating a slight disconnect; another opportunity for some humor.

Given the short’s borrowing and refinements on previous Bugs cartoons, Jones maintains the trend by making a true throwback—Porky’s Hare Hunt is channeled through Bugs’ haughty declaration of “Of course you know, this means war!”. The comment, of course, would become one of his trademark catchphrases, and one Jones himself used liberally. It becomes easy to forget that he was imitating—poorly, per Ben Hardaway’s direction—Groucho Marx in the aforementioned cartoon.

Maintaining his on and off fluctuations, channeling very faint vestiges of his prototypal self, Bugs smacks his not-quite adversary with one of his gloves. A most disturbing sight—not from the unwarranted violence, but the intimacy and discomfort of seeing Bugs’ bare hand. Coloring it all gray instead of white renders it even more “naked”, contributing further to the cause.

Bugs’ exit doesn’t flow as cohesively as other shots in the short due to some abrupt cutting and awkward hook-ups. We end on Elmer chasing after Bugs, with the camera cutting directly to Bugs walking into Elmer’s bedroom. While that in itself should work, the cut is abrupt and Bugs is barely on screen for it to register (as well as his continued marching seeming awkward in motion.) It almost seems as though Elmer morphs into Bugs, as both shots share a similar composition that bleed into each other. This is of course not the case, but it is nevertheless an odd cut that is a bit disorienting by accident.

A very subtle but amusing character beat unfolds when Elmer finally bursts into the room. He reaches to turn on the light switch, but has to actually look to see where he’s reaching—his hand grabs aimlessly before he checks himself. With renewed confidence, he turns on the light with his other arm; such a differentiation calls more attention to him making such a change. It all unfolds quickly and is very easy to miss, but is an enriching, attentive detail.

Bugs’ “TURN OFF THAT LIGHT!” would become a staple catchphrase of the wartime cartoons. They would, of course, propagate in the propaganda cartoons, riffing on air raid wardens preparing a town or neighborhood for a potential air raid and making sure no one house or place was still visible in the nighttime. This proved ample opportunity for Mel Blanc to run with his trademark scream; the ending to A Tale of Two Kitties is one of the more notable examples of such a device.

Out of meek impulsivity, Elmer obeys. His wild, elastic scrambling proves to be a great antithesis against the close-up shot of his creeping realization. Between many shots in this cartoon and Good Night, Elmer, Jones seemed particularly fond of depicting Elmer in moments of slow burning realization or anger. It satiates his itch for frustration comedy, as well as giving his characters more humanity and depth by indicating a step by step walkthrough of their thought process. Sure, in abundance these beats have been known to slow down the pace of a cartoon or two. To an extent, that is true here. Regardless, he was getting a handle on how to apply it best and where to apply it. Likewise, the drawings of Elmer themselves are all very tight and appealing. Hard to dismiss.

Bold lighting choices in the adjoining wide shot is also hard to dismiss. Shrouding most of the bedroom in an inky void is not only atmospheric and bold, it also gives more weight to the act of the lights being turned off. Per Bugs’ demand, the room is now in complete darkness. Thus, it justifies Elmer’s anger as he prepares to confront his pet—he wanted the light on. It is not. In fact, it is suffocating my dark. Thus, a discontented Fudd is born and justified.

Pitch darkness also aids in enunciating the spectacle that follows—a beautiful, beautiful caricature of action. None of it makes any sort of sense whatsoever. It is all exaggeration, all caricature, all approximation. There is no way any sort of hit, punch or restraint regarding Bugs would prompt a fiery explosion. Likewise with the extravagant and incredibly, incredibly effects animation that completely douses the screen in a colorful spectacle not incomparable to a fireworks show. It’s amusing, it’s whimsical—it eases any of the pain brought on by thinking about Elmer clobbering an animal—and it keeps the audience in suspense. What is actually happening beneath those fireworks, explosions, whistles, and initial smacking effects? It’s all up to our interpretation and imagination. A gorgeous scene that is pure fun and looks great—it’s truly amazing how quickly the effects animation has tightened and progressed in the past few years, along with everything else.

We never get official confirmation on what exactly is happening; Elmer and Bugs are depicted as mere streaks of paint as they rush out of the bedroom and down the stairs. Furniture flies in their wake to again demonstrate the extent of their wrath; animation of the furniture barricading Bugs out of the house in particular suffers from even timing and spacing, feeling mechanical and odd, but that could also very well be intended. It could hint at the laws of physics and the furniture working in Elmer’s favor, doing all of the hard work for him and seeming to lock Bugs out with utter ease. Given the many subtleties and nuances and innuendos in the cartoon thus far, it’s not completely out of the question… but mere technical awkwardness seems to be a more plausible justification.

No matter the reason, one thing is certain: Elmer is finally free to enjoy himself once again. The elation of his newfound carefree attitude is highlighted through the way he steps over his fallen bathroom door—no attempts to fix it or even scoff at it. That can wait. For now, he’s just glad to be rid of that pesky wabbit; twirling the ties on his robe as he walks is another great beat that indicates his almost juvenile elation. A peppy accompaniment of “Fountain in the Park” drives all of the above points home.

So, to find Bugs sleeping in his now tattered bed comes as a great surprise. It should be expected, of course; a truly happy end is too disappointing and not a part of the short’s prevailing irony. Instead, it benefits again from its nonchalance and straightforward execution. No questions, no bloated realizations. Just Bugs again screaming “TURN OFF THAT LIGHT!” with twice the ferocity (and twice the Mel Blanc-ness) than before. That’s all, folks.

Or is it? Historian Thad Komorowski relates that the copyright synopsis for the short follows a different end: “Disgusted, Elmer leaves the house to the rabbit.”

It’s a mystery as to why this ending was cut. Perhaps it was too similar to the ending of almost every Bugs short, prototypal or “official”, thus far: Elmer leaves in anguished sobs in A Wild Hare. Elmer has a mental break towards the end of the cartoon in Elmer’s Candid Camera; a slightly similar tune, but one that falls in the same pattern nonetheless. Hare-um Scare-um has its own hunter hurr-hurring and hopping around like the prototypal rabbit (which in itself is a direct take from Daffy Duck and Egghead, where Egghead whoops and cartwheels like Daffy in capitulation).

While the end here is abrupt due to the cutting, it does seem to be the better alternative—it matches the blink-and-you’ll-miss-it tone maintained throughout the short, and allows the audience to process and stew in the enigma we know as Bugs Bunny.

Like many shorts of the era, Elmer’s Pet Rabbit can be viewed at through various perspectives. To an everyday viewer unaccustomed to Bugs’ evolution, it may seem like a complete misfire—why are his gloves yellow, and why does he sound like that? Why is he such a pompous jerk? How could anyone like this character? This short is too slow and bloated. Thank goodness Bugs isn’t like that now.

Likewise, there’s the inverse: this is an incredibly fun, playful outing for its time that really demonstrates just how quickly Chuck Jones is making progress through his cartoons, and how quickly Bugs is making a name for itself. It has its issues, undoubtedly, but its a great, motivated effort for its time. I myself am much more inclined to adopt the latter perspective.

Again, this short isn’t perfect. There are beats and moments that could stand to be cut or sped up, the drawings at time can be more lumpy and vague than others, and there are some awkward directing decisions or oversights.

Regardless, especially with the knowledge that this short was rushed through production, it turned out exceptionally well given the circumstances. So many nuances in the acting and implications, encouraging the audience to dig deeper and process what’s on the screen. Awkward as Bugs’ voice is, Jones makes it work within the bounds of the short, and the monologue as Bugs stuffs his face is perhaps the greatest scene in the entire film. Experimentation with lighting and layout is, for the most part, successful and poignant.

Many beats, gags, character traits or even implied commentaries would be refined to greater lengths in Jones’ heyday. This short may not be as groundbreaking as 1942’s The Draft Horse or The Dover Boys regarding comedic inspiration and a deviation from his usual fodder, but it is very important nonetheless. Very important for Bugs, very important for the Bugs and Elmer dynamic, and very important for Chuck Jones.

A more candid note to wrap things up: I myself have always regarded this as a sort of “guilty pleasure” cartoon. There’s nothing to be guilty about (as this review hopefully proves!), but I was always drawn in by the novelty of the gloves and the voice. It is very rewarding to finally have justification and context as to what makes this short crack. I wouldn’t begin to consider it against the shorts made in the coming years as one of Bugs’ best, but it is a cartoon that becomes much more likable when knowing what lead up to it, what it lead to, and the nuances that make it so entertaining. Indeed, that little gway wabbit seems to be onto something.

.gif)

It's so weird to hear Bugs with that voice... I know that his voice in A Wild Hare was also slightly different from the most usual one, but here in Elmer's Pet Rabbit, it doesn't sound like Bugs...

ReplyDeleteAnyways, I think that I'm starting to identify each director's style. This short SCREAMS "Chuck Jones" to me, and I'd like to thank you for teaching me the basics. The timing, the art style and the expressions take so much of the first works of Jones as director, but at the same time, they're starting to move to the later style of Jones' glory days.

This was a fun read, just like the rest of your works, author. Sadly, I won't be able to read your blog again until my next vacations. But I cannot wait to come back! 1941 has many awesome LT shorts in my opinion: 'Tortoise beats Hare', 'Porky's Preview', 'The Henpecked Duck' (my 2nd favorite of the early Daffy), 'Rhapsody in Rivets'... I wish you a lot of luck, author! Until next time!

funny thing: this actually used the model sheets drawn by mr. givens, instead of the additional ones by mckimson

ReplyDelete