Release Date: January 11th, 1941

Series: Looney Tunes

Director: Bob Clampett, Norm McCabe

Story: Warren Foster

Animation: John Carey

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Porky, Rooster, Prisoner, Lew Lehr, Doberman, Long John, Humming, Dog, Race Announcer, Photographer), Robert C. Bruce (Narrator, Long John)

(You may view the cartoon here or on HBO Max!)

The first Looney Tunes short of the new year prompts new opening titles—“new” used liberally. It’s essentially the same as the last, with Porky bursting out of the drum, but tightened up to seem more cute and appealing. These title changes used to come with a change in the actual cartoon seasons, often around September or so (justifying the short lifespan of the previous drum title), but now seem to be instated at the beginning of the year. 1942 follows the same pattern.

We thereby open with the final joint directorial gig between Bob Clampett and Norm McCabe. As was the case in The Timid Toreador, it’s difficult to divide the short into the Clampett half and the McCabe half with unadulterated subjectivity. Parts of the short have earmarks of both, but that in itself could get misconstrued seeing as McCabe was an animator under Clampett’s direction. What one may speculate to be his directorial touch could just be him fulfilling his everyday animation obligations.

Nevertheless, as was also the case with Toreador, the credits and background of the production continue to be the most interesting part of the short. Per the title, the cartoon adopts the structure of newsreel as a means to demonstrate various spot-gags.

Newsreel parodies are far from new in the Warner catalogue, stretching as far back as 1933’s Bosko’s Picture Show. Cartoons presenting themselves as a newsreel, however, is a little more novel. That novelty is introduced through the opening shot of Porky sitting at a news desk, here to bring “the leh-le-leh-eh-latest news of the we-wee-we-ehhh-the latest news of the weh-wee-wee-ee-weh-wee-ih—the past seven days.” The shot itself is incredibly brief and a bit static, unceremoniously fading out to black, but it succeeds in introducing the audience to the format. John Carey’s layout drawings seem to have been closely followed by the designated animator—there’s a good possibility that it was McCabe himself.

Our first glimpse of satire is teased through the fairly innocuous silhouette of a rooster; the iris opens to reveal “PASSE NEWS” in bold typeface at the top, in reference to Pathé News—a producer of newsreels based out of the United Kingdom. Ironically, Warner Bros. would see ownership of the producer in 1958, where it was rebranded as Warner-Pathé and would continue production up until 1970.

Thankfully, the pun is an afterthought rather than the sole source of a gag. That itself stems from the rooster’s borderline effeminate declaration of “Cock-a-doodle-doo!”. Blanc’s vocals are inoffensive, yet charming; the juxtaposition between the side smacking and wing flapping and the actual result proves to be effective.

Having established that the tone of this short will be lighthearted, a comedic subversion on newsreels—with varying levels of “comedic”—momentum trucks along as the formula is established. A headline offers insight to the coming gag, which is either excessively faithful to the text or completely divorced. Here, the title card gives insight about the Elk’s Club staging a parade. A location of “Postoffice, Pennsylvania” in the corner coyly informs the audience that not is exactly what it seems.

Deceptiveness extends even to the filmmaking. Robert C. Bruce narrating the parade is jarring and sudden, as he seems to come out of nowhere. Admittedly, it’s probably the most logical choice—Porky’s voice might become a bit of a distraction, taking away from the gags on screen, but the change is nevertheless odd considering Porky introduces himself and his role in bringing the news. Contractual obligations are to blame more than anything, mandating Porky be in every Looney Tunes short, but such a workaround here seems flimsy and lacking in confidence. Even if, arguably, such a workaround is probably best for the immersion of the short.

Here, Bruce lambasts about the Elks marching in perfect synchronization, the camera carefully steadied on their legs and torsos.

Thus, the reveal to their status as actual elks comes as a bigger surprise. Focusing on the legs before the reveal is an inverse of Avery’s own “marching in perfect synchronization” gag, as seen in shorts such as Detouring America. Avery’s execution feels a bit less rigid and forced, but there is a slight whimsicality in this portrayal that is native to Clampett’s sensibilities.

One title card preceding another seeks to pad time, save money, and get some laughs. Clampett himself later mentioned in interviews that sign gags and wordplay were almost a guaranteed laugh in those days, as well as the easiest way to achieve them. One wonders if audiences in early 1941 truly found the disconnect between “personalities” and “poisonalities” to be as side splitting as it tries to be.

Thankfully, a segment dedicated to a so-called tax expert is one of the most memorable sequences in the film. Not necessarily for its humor (which is arguably stronger than much of what is present in the short), but for John Carey’s feats of strength as a powerhouse animator. It’s some of his most complicated personality animation to date—construction is solid, tactile, perspective is intricate and complex, accents such as chin flicks and head tilts carry guided emphasis. With Carey’s even timing sense, the animation may seem uncanny at first glance, but it remains a gorgeous example of his competence as an animator and just how valuable he was to Clampett’s (and later McCabe’s) unit.

All of his head swaggling and chin tipping accompany a rant on how he’s never had to pay his taxes: “The smart guys like me skip it!” Blanc’s slimy, suave vocal deliveries are beautifully caricatured through the animation, and all around pleasant to listen to.

Such illustrious animation and voice acting amount to a powerfully ironic punchline. A pan out from the camera reveals the tax dodger to be a proud resident of a prison, proudly engraved in cold, stone lettering. The stone façade seems more archaic and crude in comparison to regular concrete walls; a purposeful piece of art direction, as it almost makes his conditions seem even colder, vacant, and more unpleasant as a whole. His contented grin is empowered as a result, an effectively amusing incongruity.

The succeeding sequence, not as amusing. If anything, the art direction is the most striking takeaway—the establishing layout shot of the Swiss battleship in question is rightfully gorgeous, the camera angles so as to give inflated importance to the ship and make it tower over the audience. Dick Thomas’ handling of lighting and value allows relationships between the foreground and background to pop, encouraging visual clarity and a general sense of artistic enrichment.

In spite of its comparative visual grandeur, it doesn’t exactly mask the flimsiness of the gag—the battleship sinking immediately upon release is expected, and it could stand to be much more exaggerated and quick than what is actually present. Perhaps such an opinion stems from exposure to Avery’s spot gag cartoons, whose timing and execution could often save the most transparent of gags.

As though to compensate for the sense of routine, the following sequence adopts an antithetical attitude and is proudly bizarre: Porky narrating a dog show as a caricature of comedianLew Lehr.

It serves as a testament to Lehr’s popularity, whose catchphrase of “Monkeys is da cwaziest peoples!” must have had people rolling in the aisles given its reuse in so many Warner cartoons. It, more importantly, seems like an attempt from Clampett (and McCabe) to keep Porky relevant to the cartoon—perhaps they didn’t want him to narrate with his regular voice, but putting on an inexplicable impression would make him more captivating. Or, it could just be another testament to Clampett’s love of pop culture references.

Porky maintains Lehr’s vocals throughout the entirety of the sequence covering the dog show—nearly a minute. Coincidentally, some of the gags offered within that time are some of the most sound in the cartoon—perhaps there’s some magic behind celebrity impersonation after all.

Comparatively concentrated involvement from McCabe may lie in a scene of a bird dog (“Here’s a dog that always gets the buh-bee-beh-bird!”, however, is definitely of Clampettian sensibilities) flying like a bird and settling on a perch. Namely through the layout and execution; indeed, the dog soars through the air, looping in and out of perspective, bird sound effects cementing the illusion and giving a coy permanence to it that enhances the gag. However, the dramatic angle of the birdhouse is rather synonymous to a similar, albeit more elaborated layout and camera pan in The Ducktators. While Clampett could get inventive with his staging, as A Tale of Two Kitties proves—a short he did the layouts for himself—he wasn’t necessarily one to stage such elaborate pans for a single, one-off gag that isn’t very relevant to the remainder of the cartoon.

Conversely, a gag involving a “Coney Island Hot Dog” seems to be just as vacant in its application to the film as the joke itself. Leaving the bird dog, the camera fades to black... only to jump directly to the dog, no fade to bridge in back in, and giving an added jolt that disrupts any momentum this short has. Cutting to the next gag isn’t as egregious, but a dissolve of a fade could still stand to smooth out the bumps.

Thankfully, a spotlight on a Doberman Pinscher heralds one of the most memorable gags of the short. While the punchline remains easy to guess—confirmed through the dog’s joyously affable declaration of “Yeah, I’m a pincher!”—the execution is energetic, dedicated, and funny.

Again, John Carey is to thank for the volumetric construction, clear posing, and sincerity in depicting the dog’s sheer joy, as though pinching other dogs and people awakens a carnal desire within him. Blanc’s guffaws and giggles and “Pinch-pinch-pinch!” provide equal weight in carrying the charm and energy, matching the earnest of the animation, and the rapid panning back and forth to follow the dog injects a palpable fervor that is perfectly representative of his flighty, mischievous glee.

Even the introduction is strong; the stolid exterior of the dog allows for his hysterics to shine as a strong, effective incongruity. As much of its name may be a giveaway, the audience likely wouldn’t have been able to predict the visual and vocal spectacle beholden to them. The dog seems to undergo a crazed metamorphosis in real time—a specialty of Clampett’s.

A sequence highlighting a massive town flood feels much more static and sleepy in comparison. Some of that is, of course, intentional—such eerie stillness of the floodwaters enhances the severity. Likewise, the town being a sleepy, cornpone village benefits from the same direction. Still, much of it comes down to the relative flatness of the gag.

Interestingly, Clampett’s comic roots and infatuation with pop culture manifest in some background details. An “Adam Lazonga” on the general store sign serves as a nod to the long running Li'l Abner character.

Robert C. Bruce returns to voice both the narrator and one of the victims of the flood—a wholly indifferent yokel who seems to pay absolutely no mind to the flood. “They don’t bother me none,” is his astute verdict.

“…but my wife is very unhappy!”

To cement the shift in tone, Mel Blanc supplies the second line in a nasal, effeminate register. It accents the disingenuous setup, the subversion of his short little wife having been submerged in the floodwaters this whole time. Likewise, her own spitting out of the water cements the permanence of the environments. Environments that do a lot of the heavy lifting—less time and money spent if artists only have to draw characters from the torso up.

War continuously looming overseas heralds an increase in war-related gags and cartoons, as mentioned in the past few reviews. Norm McCabe especially would specialize in propaganda cartoons—not particularly by choice, but due to his role as the chief black and white unit. Technicolor cartoons took longer to produce, whereas the cheaper black and white cartoons could be ushered out the door quicker. Thus, topical gags and themes could still remain fresh.

As such, the next two minutes are dedicated to showcasing a variety of wartime gags. Antics in the air, on land, and in the sea. Porky marching through the frame in a Union uniform, fifing “The Girl I Left Behind Me,” serves as a somewhat desperate, vacant attempt to keep him relevant to the short. A losing battle.

Of the three segments, the weakest is probably the first one: an exploration of a tank’s invincibility. That in itself isn’t so much a problem—the crescendo of the gag is convincing, with the tank traversing a variety of obstacles that increase in severity. First a wall, then a trench, then an entire building. While animation of the tank isn’t exceptionally smooth, the rigidity accentuates its brute force and bulkiness, such as the perspective of the machine dipping in and out of the ditch. The visuals feel more committed and purposeful, believable; just having the tank keep moving forward on a rolling pan would be too anticlimactic.

Instead, the anticlimax is saved for the punchline: an advertised “tank trap” being a giant mousetrap. It fits with Clampett’s mischievous sense of humor, but could stand to have a topper. Perhaps the tank were to squeak like a mouse or try to wriggle free. Instead, just presenting the gag as is likens it more to something out of Ben Hardaway’s mind than Clampett’s.

A jellyfish swallowing an ocean mine admittedly spurs an equally stupid punchline, but any stupidity is said with affection more than annoyance. Its whimsicality feels more native to Clampett’s directorial tone, and does genuinely seem like a gag that is tailored to his tastes. Comparatively, the mouse trap is more generic.

Six varieties of jelly flavors dropping from the screen after the mine explodes in the jellyfish’s stomach is not. Going so far as to depict the containers in differing values encourages believability of the gag—the variety is more effective than all containers being the same hue and labeled differently. A topper of “AND lime” instead of just “lime” indicates a clever self awareness, leaning into the advertisement aspect. Ditto with the sign boasting “SIX DELICIOUS FLAVORS”. That little plug of advertising gives the gag sentience, awareness, and eases any potential blandness that could stem from the impact resulting only in jelly jars. Clampett would reprise a synonymous gag in The Great Piggy Bank Robbery to similar effect.

Likewise, the buildup to the punchline is helpful. Bruce’s orations regarding the mine and his attempts to coerce the jellyfish out of ingesting it introduce a sense of gravity and conflict into the situation. A coherent build-up allows the audience to become more invested, and for the punchline to seem more warranted and surprising. The design of the jellyfish being a throwback to some of Clampett’s earliest films, such as Porky’s Five & Ten, moreover instills a sense of belonging and purpose. It feels like it belongs in a Clampett cartoon.

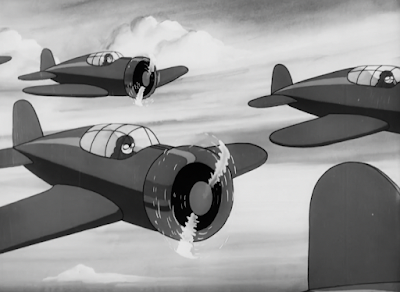

And, finally, a triple threat for the segments in the air. The first two are middling but acceptably plucky—plane engines hum a melody of “Aloha Oe” to give Bruce’s narration a literal representation, whereas another plane’s wings flap like a bird. Cuts between the gags, however, are somewhat stilted. Both end on a fade to black, and immediately cut to the next scene without a fade in—synonymous to some of the cutting issues earlier on in the cartoon.

Again, it isn’t a major detractor, as it’s clear when both gags start and end—the sequences just feel more abrupt and “rushed”, as though there’s a zealousness to sweep them under the rug and get to the next point of action. Such a maneuver is more effective when the content on screen is genuinely climactic, grandiose, or exciting. All things these plane gags are not.

Two interceptor planes fighting with each other like dogs is the strongest highlight of the three. Not necessarily due to the content of the gag itself, but what it represents—in the same way the jellyfish is a throwback to earlier Clampett, so is this gag. The planes circling each other and barking like dogs, nondescript star effects and brush lines seeking to caricature and specify the action, is particularly reminiscent of a cat-dog hybrid fighting with itself in Clampett’s opus, Porky in Wackyland. Here, the gag feels more like an approximation—motion is less smooth, action is less clear, with graphic flourishes and sound effects carrying more weight than the actual drawings, but it too feels like a genuine product from the mind of Clampett. Even if it’s not riotous or intensely engaging, it does feel at home.

John Carey continues to supplement Porky’s animation in the corner iris of the screen, trying to make the most of what limited time he has. His animation and draftsmanship continue to be rife with appeal—head tilts and accents on movement try to seep as much life into Porky as possible.

With sports now the theme of the cartoon, Mel Blanc supplements nasal sneers as a horse race announcer as we track a high stakes race between “Specify” and “Chaladon”. McCabe’s drawing style is much more poignant in this section, particularly with the jockeys. Spherical heads and proportions—Clampett’s own take would likely have some more exaggeration and differentiation between shapes and sizes.

Worth noting, a perspective shot of some jockeys turning a corner is repurposed from Ben Hardaway and Cal Dalton’s Porky and Teabiscuit. Designs on the horses are comparatively more chiseled and specific, shedding the 1939 balloon design influence of the former cartoon, but the vagueness of the human designs do remain somewhat awkward and vacant.

“They come around the turn and go into the stretch…”

Horses apply accordingly. McCabe’s gag sense and timing again seem stronger through the execution—a very matter-of-fact literality that maintains the pacing of the race. Clampett’s own take on the gag would likely have a larger emphasis on the gag, whether it be the cinematography placing an unabashed focus on it or just the transformation itself seeming more elastic and caricatured.

A photo-finish is, likewise, taken very literally. Coy posing on the horses is especially amusing; as is the differentiation in their posing. One crosses its hooves, fluttering its eyelashes, while the other looks off-screen in false modesty. Symmetry of the composition unites the staging, but the slight variations in poses maintain a sense of organic appeal and life.

An intriguing directing move tops off the gag as the camera fades to black. In an attempt to break the fourth wall, the cloud of dust stirred up from the departure of the horses erupts overtop the environments, momentarily shrouding the screen in dust before formally arriving to a fade. Effects animation of the dust cloud is a bit crude—form is very even, bubbly, nondescript, and lacking a general sense of direction. John Carey’s proficiency in effects animation would have been a better fit, but that also comes at the expense of Carey being such a superstar talent in general.

Our final stop of the short resides in “Goon Lagoon”, following a swim race with “the nation’s finest swimmers.” Again, McCabe’s influence is much more palpable with the spherical design of the humans. Carl Stalling’s accompaniment of “Trade Winds” is likewise a number that can be heard in a handful of McCabe cartoons—it serves as a prominent motif in his first solo effort, Robinson Crusoe, Jr.

A laughing musical arrangement upon the arrival of the punchline seems to be yet another McCabe trademark. Said punchline is hardly new to these shorts—swimmers go in the water, emerge as alligators in the same swim gear, implying their fate has been sealed. Execution is again rather literal, with the self awareness of the laughing music doing little to render it more amusing. Regardless, timing on the swim cycles themselves is rightly quick and energetic. Crude drawings, literal execution and somewhat annoying self awareness nevertheless don’t offer excessive favors.

One final newsreel reference solidifies the cartoon’s end. Movietone’s slogan of “Sees All, Hears All, Knows All” is twisted into “Eyes, Ears, Nose and Throat of the World”. She Was an Acrobat’s Daughter parodied the same slogan with much more effective brevity: “Sees All — Knows Nothing.” Regardless, Porky feeding a sausage into a meat grinder (instead of rolling film) is an amusingly morbid visual that the audience is left to ponder as we iris out.

Porky’s Snooze Reel is definitely one of Clampett’s weakest films to date. Perhaps it would have been more coherent without the production troubles behind it (such as McCabe having to fill in for him), but even then, one gets the sense that the premise was dead on arrival; the gags themselves are either not very funny to begin with, or don’t live up to the potential they have to be more amusing. Porky’s shoehorning is excessively transparent, as this obviously wasn’t a cartoon written with his strengths in mind (with Bruce’s narration immediately picking up after Porky’s introduction being a pretty big middle finger in itself), and as a whole remains not very captivating.

Some of these criticisms are also somewhat unfair; the short was probably much more successful at the time of its release, when newsreels peppered every movie showing. Audiences would have caught the allusions to Movietone right away and would be able to appreciate the format of the cartoon much more than viewers would now. That’s the thing with many of these cartoons—they weren’t made with foresight in mind, and it’s not their fault for not aging as well. It would be conceited to expect otherwise. It’s a product of its time.

Regardless, there are many other newsreel parodies and respective products of their time that do have genuinely amusing jokes and conflicts. She Was an Acrobat’s Daughter was released in early 1937, and still holds up relatively well with some of its gags. Even The Film Fan, whose newsreel portions of the cartoon are the weakest, maintains audience intrigue with the storyline of Porky getting distracted on his way to the store and watching the newsreels. There’s at least a solid beginning, middle, and end, and there are some beats genuinely written with Porky’s character in mind.

Here, Porky could easily be exchanged with any other one-off character and the short would barely change. The jokes again just don’t seem very motivated, with the best gags of the cartoon being callbacks to previous, more thoughtfully executed alternatives of similar beats. John Carey’s animation remains a standout, with the tax fraud segment especially serving as a pinnacle of his talents.

Regardless, Snooze Reel is the perfect encapsulation of the majority of Clampett’s cartoons from around 1931-1941. Shoehorned, vacant, having some drive with certain ideas but unable to allow them to reach their fully realized potential. Excessive mediocrity of the cartoon is more frustrating than sheer incompetence—this short isn’t a complete dud, but the fact that it isn’t much of anything at all is almost worst. At least a bad cartoon elicits some sort of reaction. Instead, the short rather ruefully lives up to its name.

No comments:

Post a Comment