Release Date: January 18th, 1941

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Friz Freleng

Story: Jack Miller

Animation: Herman Cohen

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Ants, Rochester)

(You may view the cartoon here!)The Fighting 69th½ sees the final writing credit for storyman Jack Miller. While his stint at the studio was a short one overall, his first credit being for 1938’s Have You Got Any Castles?, it was certainly a notable one—Cracked Ice, Hamateur Night, Bars and Stripes Forever, and Thugs with Dirty Mugs are all some of the strongest shorts of their respective eras. Likewise, anyone who has the honor of writing You Ought to Be in Pictures is automatically deserving of accolades.

He would move to George Pal’s Puppettoon studio, and had a stint at Filmation in later years. It’s worth nothing that his time with the Looney Tunes characters doesn’t end here—he would even work on a Puppetoon that features a then refined and recognizable Bugs Bunny, whose animation was supplemented by Bob McKimson. The leftmost image is an April 1944 article of Coronet Magazine, which cites Miller's involvement in the films; more specifically, the aforementioned cartoon,

Jasper Goes Hunting. You can see the clip for yourself here—a brief warning for stereotyped caricatures.

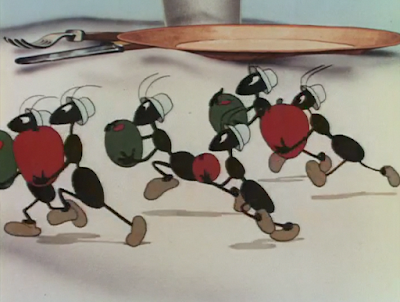

A parody of the 1940 Warner film, The Fighting 69th, Freleng caricatures trench warfare between ants. Throughout his career, he would uphold a longstanding tradition of handling stories with bugs: ants, mosquitos, worms, spiders, and so on. A 1947 rehash of sorts, The Gay Anties, would borrow a number of gags, beats, and general ideas from this short, giving an indication to its topical longevity with Freleng.

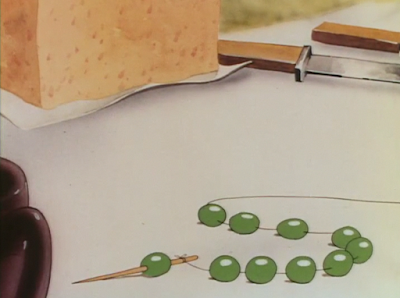

Given that the short is about ants—mere picnic ants at that—the innate domesticity of the topic is conveyed through multiple establishing pans. Watercolor paintings of a picnic tucked away in the woods, food out in the open and currently unattended depict a scene of unadulterated idyll. In spite of the intended stagnancy, life is conveyed through artistic details so as to give the environments purpose. For example, a gently toppled jar of olives indicates that there is indeed some life behind such a setup. The picnic wasn’t arranged for the convenience of any meandering ants in mind; humans were here, making the impending invasion seem all the more like an intrusion.

Indeed, a camera pan right introduces our future invaders. Red fire ants stream methodically in and out of their holes; a flute accompaniment on top of Carl Stalling’s music score accents the flighty sense of routine to caricature the motion and give it a point of focus. On another note, background details are handled with convincing organicism. Airbrushed grasses in the background indicate a depth of focus, and the differentiation in grass blades—some straight, some curved, one bent at the tip—give balance and visual interest to a layout that is carefully arranged to guide the audience’s eye. Direction of the ant hills, the dirt, and the grasses all slant to nudge the eye directly to the ants.

The camera provides much of the storytelling in the opening, as indicated through a sudden pan left. Such signals the audience to a change—there is a brief pause, as the viewer halts to ponder what this could mean. Out comes an ant, parting the blades of grass and grinning at the food offerings in front of him. Telegraphing his arrival just a few seconds before it is fully realized, ironically, instills an organic flow in the filmmaking. While it feels as though it would do the opposite, giving away the motivation of the scene too quickly, there being a slight lag creates a natural imbalance that embraces the audience’s role as a spectator. Events don’t just unfold on-screen at our convenience. There are lapses, pauses, skips—all purposeful in immersing the audience into their role as a viewer. Just the mere act of the camera panning ever so slightly feels akin to catching something out of the corner of one’s eye.

Likewise, the sudden sentience of the ant proves to be a surprise in itself. It registers as a notable parallel against the crowd displayed just seconds before, drone-like in their symmetry and obedience to their holes. Here, this ant stands on two legs, is able to maneuver its arms, and has clear facial expressions. All of this pastoral fluff is purely a front—this sudden anthropomorphism is what the cartoon truly represents.

All of the above apply doubly with the introduction of an ant at the opposite end.

Symmetry is a major driving force of the cartoon. Its clarity offers ample room for juxtaposition and similarities—much of the filmmaking adopts a “half and half” approach, as we study the antics of the red ants, the black ants, eventually merging together in a single shot of both factions arranged in the same pose at opposite ends, and so on. It allows conflict to register easily and to be taken advantage of.

Thus, such is Freleng’s exact course of action as both ants dart for the available food at the same time. As they get closer to approaching the prize, camera cutting grows faster. Quicker cutting indicates a growing climax—more energy broiling in the surface, higher stakes, greater tension, as well as hinting at an eventual collision between the two. Little details continue to differentiate the ants so as to, again, avoid feeling too clean cut or perfectly similar; for example, the red ant runs with his fists balled, whereas the black ant opts to have his arms outstretched. They maintain what little individuality they have, giving additional gravity to eventual conflict through these little differences. The effect wouldn’t be the same if their only differences were their color.

Conflict nevertheless arrives through an argument over an olive. Rather than having either ant engage in a long-winded spiel as to why they’re entitled to the food, a mere back and forth “Ahhh, no ya don’t!” “Ohhh, yes I do!” gets the point across just as successfully through its brevity.

Back and forth “Ya don’t!” “I do!”s are, tangentially, related to one of the most memorable dialogue gags of the studio. The crescendo in which both ants bicker, voices quickening, tone rising, music boiling is identical to a similar scene in Freleng’s Duck Soup to Nuts. That sequence harkens one of the earliest uses of the ol’ switcheroo, most commonly associated in Chuck Jones’ hunting trilogy of cartoons. In this case, Daffy insists Porky’s an eagle, and Porky insists he’s a pig—their arguing grows more rapid in the exact way seen here, with Daffy throwing the wrench in the works and resulting in Porky proving his status as as eagle.

It’s not to say that this one-off altercation is directly responsible for pulling the weight of such a memorable gag. Hardly the case, but the fact that Freleng was able to imitate this almost exactly synonymous routine in a short made three years later without said short feeling antiquated speaks to the success of the timing and delivery here. Rightfully quick, rightfully energetic, and rightfully motivated.

Arguments are instead stifled through the red ant slamming the olive over the torso of his adversary. Emboldened by his humiliation, the opposing ant enlists in the age old wisdom of Groucho Marx to christen his declaration: “Of course you know, this means war!”

To further expound upon any humiliation justifying his decisions, the and falls flat on his face. Thus, the broken olive around his torso slips down, momentarily representing an ill-fitting pair of shorts that further seeks to assault his pride through such playful, “juvenile” visuals.

His definition of war, as it turns out, is elaborate trench warfare. Uniforms, bugles, drills and all. In a way, the short is a more sophisticated take on What Price Porky—both shorts involve ridiculously elaborate WWI style brawls over food. Freleng leans into the cinematography and ambience, as indicated through a thirty second montage both adding gravity and completely lampooning the absurdity of the situation.

Musical timing and rhythm is, to be expected, one of the main focal points: a shot of the ants trudging through mud has even the sound of the mud suctioned beneath their feet contributing to the musical beat. Meticulously timed and planned out, such musicality does allow the visuals to adhere to the music, and vice versa—both elements are convincingly synchronized rather than haphazardly conveyed.

Noble animation of a banner waving in the breeze is a gag in itself through such visual extravagance; these ants, seen crawling through holes just a minute before, now have the resources to create their own shiny banners with the luxury tassels. Even then, wordplay seeks to jar additional laughs from the viewers—“the 4th Alabam” serves as a nod to the 167th Infantry Regiment, often nicknamed as “4th Alabama”.

Shots of various army supplies lightly hint at the absurdity of the entire battle—surpluses of cotton and deadly insect powder, with caterpillars supplementing tank wheels, all indicate a joyous extravagance that is ironic yet committed. Perspective of the supplies is likewise convincing in its solidity and immersion. Moving diagonally into and away from the camera introduces depth and dimension, making environments seem more interactive, as well as maintaining visual interest through varied staging.

And, lastly, a highlight of the “Royal Flying Ants” indicate that the brawl isn’t limited only to the army—even the air force is involved. All of this pageantry over a mere picnic brawl.

While the short itself may not be a feat of Freleng’s comedic strengths, it is, indubitably, a solid showcase of his eye for cinematography. Who else could delegate an upcoming 30 seconds of the cartoon to near silence and complete stagnancy in the animation? Or, perhaps the more accurate question is—who can do all of that, and well?

Part of its accessibility is knowing that, in the end, it’s ironic. Crickets drown out an incredibly moody, muted music score as the camera slowly pans across the picnic grounds. Trenches have been dug on either side, and both are densely populated. After that establishing pan, the camera trucks out to show both trenches in the same shot; symmetry continues to be a driving force of story and momentum. Ambience is rife, as is tension.

Such is the beauty—again, all of this is over a picnic. Freleng notes upon the absurdity of the situation with the sound of the crickets in the background. The sky is still light, and it is still daytime—overcast, to further embrace the atmosphere, but daytime. That is, no logical reason for crickets to fill the ears of the audience other than hammering in ambience that is so in-your-face that the only reaction is to laugh.

Purposeful as Freleng’s intentions may be, such stillness is beneficial on the surface level: it allows the sudden burst of gunfire and explosions to seem more startling and violent in contrast. Through this flurry of activity alone, the seeping domesticity of the cartoon’s opening is ravished in seconds. This isn’t some cutesy, middling tale of picnic ants fighting over the last crumb. Blood and honor is involved. Again, Freleng seems keenly aware of the comedic potential in itself. Just the implication of the warfare gets a laugh.

It’s nevertheless important to hook the audience onto the intricacies of the warfare. Thus, one ant demonstrates his plan of action, shedding light onto the deceptive intricacy of the situation. Blueprint drawings are elaborate, meticulous, but remain lighthearted and coy through “POTATO CHIPS” and “HOT DOG” labeled in such bombastic lettering. Sculpted hand animation of the ant as he gestures along the drawings is weighted, solid, convincing—if someone were to look at this single frame alone, they’d believe that the owner of the hand was that of a distinguished human’s. Certainly not an ant. Such palpable conviction to an admittedly juvenile scenario is where much of the story’s success can be traced to.

With the ants acting upon their orders, Dick Bickenbach animates a somewhat lengthy sequence of the soldiers making their cautious move. His ability to vary the spacing of his drawings and understand how to caricature motion and weight proves to be very helpful—their slow, cautious crawling thusly juxtaposes strongly against the ferocity of them sinking to the ground or scrambling to find shelter. Their trek is guided by musical timing, synonymous to the fox in

Porky’s Hired Hand tinkering across the horizon and hiding behind various trees—or, more colloquial known as one of Freleng’s trademarks. Such musicality introduces a lightheartedness to their movement and mission.

Knowing that it would quickly grow redundant to cycle through halting, ducking, and so on, the ants occasionally seek food for shelter. A slice of cheese proves convenient with its giant holes. Additional shadows are cast from the cheese upon an off-screen explosion, enunciating the impact of the blast and, again, permanence of the objects. There is a slight lag where the shadow is delayed in its disappearance, appearing to suddenly cut off the screen—a dissolve may have been more convincing to convey the fade of the shadow. Regardless, the additional effort is certainly appreciated.

While the cheese proves to be a convenient gag, it serves primarily as a launching off point. It primes the viewers for the adjoining piece of the ants diving into some moldy cheese, only to immediately scramble right back out of it. Bickenbach serves as the prime candidate for caricaturing their loose, frenzied reactions as they zip off-screen—the bounciness innate to his work maintains a playful edge that conveys mischief over distress.

A pragmatic pan right of the camera declares the cheese to be limburger. Certainly not the last joke of its kind to populate these cartoons.

Much like the meticulousness and sense of purpose in the cinematography, intricacies pepper much of the art direction. A hotdog bun is given a considerate amount of care with its various hues and shading—such makes the food seem more desirable, appealing to the ants and worthy of their attraction, as well as accenting its comparative grandiosity in size. Placing a semi-transparent glass as an overlay, with the ants running beneath it, likewise indicates depth and immersion. These are real, physical objects and not mere decorations.

Said glass also serves as a metaphorical barrier of sorts: right as soon as the ants come out from the other side, the hotdog bun lifts to demonstrate a crew of enemy ants hiding within. Having that glass separate the action instills a rhythm within the filmmaking, a drive to the action—all beneficial in furthering Freleng’s prominence of musical timing, which is best demonstrated through the ants clubbing their opponents. Skulls of the red ants are transformed into percussive woodblocks. Their decision to remove the hats off their heads and strike, rather than striking on the hats, renders the attack more sadistic and targeted.

Precise timing carries over into the opposing ants making off with the goods. Very purposeful, dutiful organization and order that lets the action read clearly. A very valuable asset, given the visual clutter on-screen between both swarms of ants and the food.

Lamentably, opportunism with the black ants does lend itself to a racial gag. It has no major effect on the story of any kind, and is merely an opportunity for Mel Blanc to flaunt his Eddie “Rochester” Anderson impression, but the big lips are rather egregious. Surely there are better ways to ping the ant as a caricature of Rochester beyond stock catch-alls that render him indistinguishable from any other stereotype.

“Forgot the mustard!” is his mouthpiece. Bickenbach’s timing and variation in action—such as the bun and hotdog settling at different times, or the mustard splashing out of the jar—maintain the scene’s perkiness and organicism. It moves with great appeal, if nothing else.

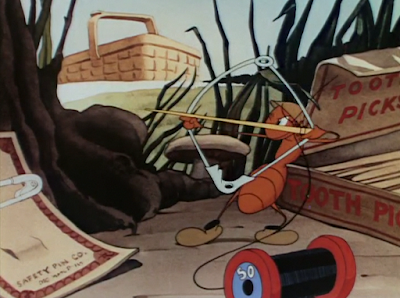

Diminutive sizing of the ants allows for equal opportunity with diminutive gags. That is, transforming tiny, everyday objects into elaborate conveniences. A more retroactive school of thought with its novelty, but nevertheless fitting with the short—it can’t all be gruesome warfare. One ant fashioning a toothpick, a spool of thread, and a safety pin into a harpoon to thread some peas boasts some tactile motion where warranted, and overall maintaining a lightheartedness that is fitting with the core of the short. When one thinks of ant warfare, these are the sorts of attacks they would default to.

That could similarly apply to an ant using the remnants of the limburger cheese as a stink bomb. With the gas mask, depth of the trenches in the establishing shot, and the quick, flurried reaction time of the opposing ants scrambling to cover it in dirt, the gag conveys a heavier, more gritty tone through such gravity. More explicit wartime imagery increases the severity. Yet, the absurdity of a limburger stink bomb (and, again, the mere concept of formicidae combat) allows the mischievous tone to reign supreme over any violence or heaviness.

Overall, Freleng maintains an effective balance of domestic and dedicated. More visceral, involved gags (such as the aforementioned diffusing of the stink bomb and the gunfire that followed) are trailed through images or gags that are playful and light in comparison.

Such is the case with a gaggle of ants stealing multiple slices of cake, a straggler returning only to fetch a lone cherry that floats in the air and drops to the middle. Here, the gag of the food itself and the synchronic animation takes precedence over the topic of warfare. Each cake slice moving in a different perspective—and so solidly at that—is impressive and visually striking. So much so that it would be reused later in Freleng’s

The Gay Anties.Similar philosophies of planned lightheartedness apply with a swarm capturing various toppings—olives, cherries, strawberries, and so on. A tiny straggler follows, as was the case with the red ants. The audience is left to wonder what there is even available for the squirt to carry.

Nothing that we, the audience, should be worrying about, as it turns out. The tiny bite out of the watermelon makes all the difference. Revealing the tiny squirt to have such exaggerated strength is an amusing reveal on its own, but the bite gives it further individuality—it really wants this watermelon for itself. Freleng’s back and forth musical timing and motifs (big ants have a more lumbering, imposing score, whereas the tiny ant’s is pitched and fleeting) gives the sequence coherence and purpose. Sharp timing and sharp execution.

Musicality and keen timing are the focus of the adjoining sequence: ants hustling to make a sandwich.

The Gay Anties would borrow the same bit, stressing the musicality with even more precision than is seen here. Even then, this scene is rather successful in itself—each ingredient has a solid construction and perspective, the intervals in which they are applied to the sandwich are weighted and sharp, and the movement supports the musical rhythm. Outside of a very few minor cel layering issues, the sequence—for all its complexity—is handled quite competently.

All of this fuss results in a classic byline of Freleng’s. Animator Phil Monroe first came up with the “HOLD THE ONIONS!” gag in

Pigs is Pigs—“He used that damned thing for years,” was his astute observation. Indeed, it’s usage in this short four years after the fact speaks for itself.

And, just as quickly as the brawl seemed to escalate, it stops. All it takes for the ants to reach a standstill is the ominous loom of a shadow over the picnic blanket. Symmetrical staging continues to be used to its advantage; here, shots of the ants peeking out from the trenches are directly mirrored, indicating a truce of sorts. No differentiation in acting or personality. Only shared a hesitation that unites them both.

A disembodied woman stuffs the remainder of the picnic into the blanket. Just like that, it’s over—the absurdity of the entire war is noted through the slow, careful, domestic manner of the woman’s cleanup. Such a bloodbath over this. Arranging the layout from an overhead layout likewise makes the picnic itself seem smaller, insignificant, drawing the audience back to reality. A warped sense of scale and perspective can really transform the stakes of the story.

There is, however, a catch—one final offering is left behind in the process.

Thus, the brawl intensifies. Even the background detail of the ants ruthlessly beating each other seems to caricature the overreaction—no elaborate missions, no drawn out conspiracy on how to attack, only senseless violence in the name of senseless violence. Conviction to such overblown severity is, again, what makes the cartoon so successful.

Even the ants have generals, touting their own brightly decorated uniforms. Such pompousness is again convincingly amusing; there is a clear hierarchy of power. All of the medals and tassels pinned to both generals indicate that this isn’t the first battle to occur. Nice, purposeful storytelling through such menial details.

Thankfully, the black ant calls for a truce. Dick Bickenbach returns again to animate the dialogue, his handiwork immediately identifiable through pronounced eye blinks, outstretched fingers, and the manner in which he animates their gestures. Clothing on the generals opens more opportunity for anthropomorphism—the hands on both ants are larger, fleshier, more whole than the stick limbs seen previously. Therefore, more room for more elaborate, human acting. A necessity when attempting to humanize these leaders finally coming to an agreement and deciding to hold a peace conference.

And that is exactly what happens. Convenience of the peace conference is just as amusing as the conference itself; ants are conveniently seated in slanted boxes that create the illusion of stands, whereas various grasses and foliage form the illusion of decorations adding grandeur to the occasion. A handful of ants in the foreground are shown to have their arms around each other in solidarity—a purposefully disingenuous directing move that seeks to emphasize how everyone is on the same page.

Likewise, a cutaway heralds the appearance of two Civil War veterans. Their nods of approval are symbolic within themselves.

As a declaration of peace, both ants opt to split the cake evenly in half.

Quick timing on the arc around the cherry is sublime. Snappy, subtle, quick, the gesture is very intentional. Hoping that the other faction won’t notice speaks to the character of the general and the feuding in general—how concrete is this peace conference?

Not very. More “

Ahhh, no ya don’t!”s ensue, as does a back and forth of both generals arcing the boundary line around the cherry. To ask “Why don’t they cut the cherry?” is fruitless, as the answer is simple—there wouldn’t be a conflict that way. Preserving the ironic ending is priority. Especially in the world of Friz Freleng cartoons.

Thus, the iris envelopes another ruthless brawl with even more senseless violence. Sheer, animalistic adrenaline of punching, kicking, and so on. Any and all rationality is a mere front.

On the surface level, the cartoon as a whole may not seem like a relative standout. And, truthfully, it’s not, compared to Freleng’s filmography ahead. It isn’t uproariously hilarious, but it is very well directed. Sharp, purposeful, full of intent. Much of the short’s comedy isn’t derived from the gags themselves, but the situations and commentary woven by the cinematography. An ant using a safety pin to fire a toothpick isn’t necessarily funny. Ants creating their own militias, power hierarchies, and battle plans over an abandoned picnic, however, is.

Bug cartoons would be one of Freleng’s staples. Likewise, elaborate bug-related gags in unrelated cartoons that reach similar levels of absurdity through playful conviction like what is seen here.

Ballot Box Bunny, for example, a Yosemite Sam and Bugs Bunny effort from 1951, has a sequence that crams many of the gags and intentions of this short in a sequence of picnic ants ruining Bugs’ endeavors to win over the public with a free picnic. Perspective shots mimic those in this short of the army supplies being shuttled through—one ant even manages to shuttle an entire watermelon on its back, just like in this cartoon. Bugs cuts a synonymously small hole in the watermelon to slip a stick of dynamite inside, and so on.

While the “Freleng insect cartoon” genre didn’t start with this cartoon, many of his bug related gags and cartoons can be traced somewhere along the line to The Fighting 69th½. Ant Pasted is another “ants go to war” cartoon, where it’s proven that the only thing funnier than watching ants fight themselves is to watch ants fight—and triumph—Elmer Fudd.

This short was redistributed to theaters not once, but twice, speaking in effect to its timelessness. An emphasis on musical synchronization, snappy timing, parallels in cinematography, prioritization of atmosphere when necessary and overall competence in animation make for a very enjoyable product. Art direction and cinematography are the biggest takeaways.

If anything, this cartoon asserts that Freleng’s influence is a necessity. His ironic humor would become a driving force of many Warner cartoons—while shorts of this era were more focused on explicit gags (such as in Clampett and Avery’s scenario) or ambience and art direction (as is the case with Chuck Jones), Freleng was interested in irony, tone, and weaving a commentary so that the deeper the audience thought about a joke, a scenario, a set-up, the more they could appreciate it. The lack of Freleng’s thoughtfulness and cynical bite in his time away from the studio can absolutely be attributed to much of the blandness of the shorts that followed. Behind Freleng comes purpose, and that is a very valuable asset that is so often taken for granted.

No comments:

Post a Comment