Release Date: September 20th, 1941

Series: Looney Tunes

Director: Friz Freleng

Story: Mike Maltese

Animation: Manny Perez

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Porky, Cat)

(You may view the cartoon here!)

The first Looney Tune of the 1941-1942 season is finally upon is, as indicated through the christening of a fancy new opening title. Porky, whose smiling mug has been delegated to his native habitat inside his drum since the 1940 season now greets us atop a fence. His pose is leisurely, nonchalant, friendly—the lettering occupies more space than he does, perhaps subtly indicating his waning time in the spotlight, but the contentedness of his posture demonstrates an easygoing demeanor that maintains his charm and likability. No longer is he obligated to pose in the spotlight with a manufactured—albeit quaint—pose of forced amiability. There’s a candidness to his leisure here that proves welcoming.

Such seems to be the theme of this coming year of cartoons. It’s still just a bit more until the shorts would really hit their stride, but the tools are all there. They have their ingredients, or are in the process of finalizing any last minute additions they need. The initial stress of figuring out the “what” has passed: now, the filmmakers can relax slightly and delight in the application of such tools.

Into the next year and beyond, the shorts continue to shed any lingering rigidity and formality. A sense of comfort and even confidence continues to settle in as the directors find their stride. 1942 is often regarded as Chuck Jones’ turning point (whose unit appears to be responsible for the pig provided in these new titles), succumbing to executive pressure in making his shorts funnier and more outrageous. Bob Clampett now has the benefit of the best animators of the studio, and was learning to use this to his advantage. Friz Freleng continued to find his footing and nestle comfortably back into the routine of the Warner studio, no longer stuck in the awkward limbo of getting acclimated after a year’s absence. Norm McCabe would luxuriate in a brief stint as director, removing Clampett of his monochromatic burden by exclusively directing shorts in the Looney Tunes series.

The Looney Tunes/Warner Bros. name has been firmly established: how it is utilized and celebrated would really begin to be realized over this next year and beyond.

There’s something to be said about this cartoon—a seemingly humble Porky short that, like so many others, has slipped through the cracks over the years—serving as a launchpad for one of Freleng’s most iconic cartoons. That Freleng used this short to serve as the mold for 1948’s Back Alley Oproar, notably starring Sylvester and Elmer Fudd, is a testament to this short’s quality… if only on a subconscious level. It says something about this short’s appeal and abilities that it was chosen out of all cartoons to be remade; something like Sport Chumpions certainly couldn’t say the same.

As is customary with these remakes, comparisons and antitheses will be explored in the analyses of the reprisals themselves rather than the initial efforts. Oproar’s presence will, of course, be a reigning consideration and referenced as necessary, but the actual delegation of what was approached differently and how will be a task for another time.

Instead, our priorities lie with Porky. Porky, and the nameless cat who completely revels in the opportunity to heckle. Freleng and writer Mike Maltese take the coy metaphor of “outside cat’s meowing equates singing” to a degree of literality that drives Porky ragged as his plans for a good night’s sleep are dashed with violent abandon.

Out of the gate, one of the short’s many strengths is its intimacy. It manifests throughout the cartoon in different ways: Freleng immersing the audience into the perspectives of both Porky and the cat, the hook centering around Porky getting settled into his nighttime routine—a candid setting all its own—or even through deliberate staging maneuvers that make a point to accentuate the aforementioned topics through an air of privacy.

Such is where we find ourselves at the cartoon’s opening. The stage is set so that the camera observes Porky’s preparations for bed outside of his window—not suffocatingly close, as a fence encourages a separation and dimension, but enough to further a sense of polite intrusion. Likewise with the window blinds making a point to obscure his face and upper body; by the silhouette alone, we already know who he is—the barrier instilled by the blinds, however, communicates that perhaps we aren’t supposed to know. A strong confidentiality prevails. Meanwhile, on the surface level, the strong contrast in values with the opaque blacks and whites encourages a strong visual interest.

We’ve been privy to the antics of Porky’s everyday life for 6 years at this point, so he certainly is no stranger to us; such is why these deliberate measures of privacy make the impact they do. Since we’re so accustomed to peering on his daily goings-on, the one time the directing hints that we should be doing otherwise makes the intimacy all the more enticing.

This sense of confidentiality so erected by the opening is, of course, intended to be shared and indulged in. Cal Dalton’s animation greets us as Porky makes his formal introduction. Writing in this particular moment indulges in some bread-and-butter exposition (“Buh-eh-buh-beh-eh-boy, am I eh-see-eh-slehh-sleepy! Now for a guh-ehh-good night’s rest,”), but proves to be a rather important development. Freleng adopts the Tex Avery philosophy of blatantness: having the characters express a hook or main idea of the cartoon immediately sets it up for refutation. With Porky making a point to establish just how tired he is, the audience is subliminally cued that the short will revolve around his quest for a good night’s sleep being violently challenged. Likewise, said challenging holds more gravity when understanding a character’s desires are on the line.

In other words: Porky isn’t going to be getting a restful night.

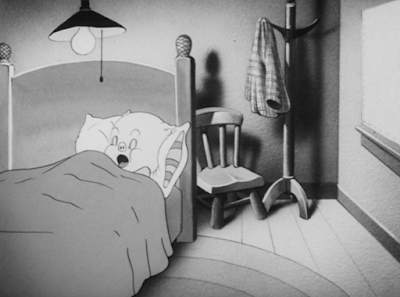

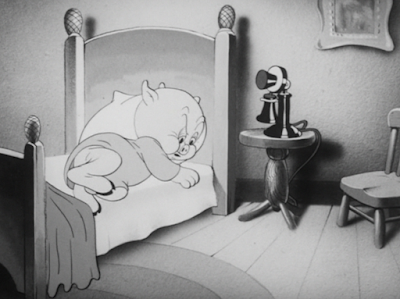

The hook of the cartoon is rendered more personal through such verbal exposition than if Porky just yawned and went to bed without saying a word. Riding on this coy indulgence of exposition, Maltese and Freleng go out of their way to express just how committed Porky is to his words by having him fall asleep before his head has even hit the pillow. Quite literally, seeing as he drags the rest of his body with him into bed after he’s already asleep.

While there’s potential for this introduction to be taken at face value and turn off the audience for how by-the-books it could be, Freleng and Maltese’s unified dry sense of humor and wit prevail. Everything is intended to seem too convenient and perfect because it is too convenient and perfect. Each second is a second closer to commotion and trouble, which is why it’s imperative that Porky is able to indulge in enough rest as he can: this is going to be the extent of it.

His aimless grabbing and reaching to turn out the light above him is a great addition that banks on these aforementioned philosophies of cloying convenience. Viewers are led to believe that he’s too tired to remember to turn off the light, which is true. This last minute correction (all executed while he’s sleeping for additional playful absurdity) ties the ribbon on the package and ensures that everything is nice and orderly. Porky’s sleepiness is sincere, but the ease in which he’s able to settle in, even after he’s already asleep, is intended to be mischievously disingenuous.

All so that the inevitable interruption brewing outside his window can serve as an even greater assault. Freleng cheats the act of Porky turning out the light through a clever bit of directorial economy: his hand reaches to grab the chain, only for the camera to cut to the façade of his house. The light in his bedroom is no more—Treg Brown’s sound effects of the chain being pulled fills the gap completely.

Just in time for a visitor to arrive. Notes to You (and, by proxy, its 1948 successor) is an instance where the cartoon is best suited under the direction of Freleng. His musical timing and overall awareness—experience as a classically trained violinist coming in handy—really allows the musical aspect in this short to prosper. It isn’t an afterthought or something that the cat merely engages in. Instead, even the most menial actions in the short are approached with a sonorousness that ties everything together.

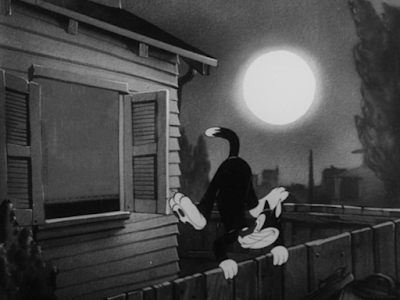

This, of course, all applies to our formal introduction of the cat. Rather than hopping up on the fence in one swift action, both Freleng and the cat milk the action to its desired degree of theatrics. One hand grabs the top of the fence, then the other, both making impact on the resonate down-beat of the bass in Stalling’s backing track of the ever appropriate “Me-ow”. A prompt, motivated drumroll narrates the act of the cat poking his head into frame. The same is said for him hoisting his entire body on the fence, never once breaking eye contact with Porky’s bedroom window.

Even entertaining the idea of preparing to engage in his eventual theatrics is a production all its own. Such renders him somewhat more intrusive—he clearly takes great delight in whatever plan is brewing in his head. There is also a knowingness behind his actions, whether it be through how gradual and “hammy” his climbing onto the fence is or his deliberate attempts to maintain unbroken eye contact with the house. This is no act of happenstance. He didn’t happen to just stumble upon this backyard fence and deem it a good spot to spend the night. Instead, his introduction conveys a story. There was a clear wait-time for Porky to turn out the light. Likewise, waiting until he was absolutely sure that Porky has gone to bed enunciates his status as an eventual heckler all the more. Yowling and screaming while Porky is changing or getting into bed is one thing. Deliberately waiting until he’s fallen asleep to delude him into thinking he’s going to get a good night’s sleep is another. Our anonymous cat is no Sylvester, sure, who proves to be the strongest aspect of Oproar, but such intensive preparation outlined here informs the audience about his line of thinking, offering dimension outside of being an obligatory no-name.

The same could be argued for the stylings in the music itself. Stalling’s accompaniment of “Me-ow” is proud, brazen, handled with a modern swing—a solid antithesis to the sleepy, sincere, ethereal backing track of Brahm’s Lullaby used in association with Porky. Song choices are representative of both characters, yes, but the manner in which they’re arranged even more so.

That everlasting sense of preparation on behalf of the cat is perhaps best represented through the inclusion of a music stand; by throwing it up onto the fence, struggling to arrange all of the sheet music together (even allowing a few pages to fall to the ground, encouraging a stronger organicism in acting through such “accidents”) indicates that his brewing performance is no act of spontaneity. A haughty connotation dominates the act of employing a music stand. A haughtiness that itself seems somewhat incongruous to the nature of the cat himself, hinted at through his scrambling frenzy to get ahold of his papers. While the sheet music alludes to a function, the sheer extravagance of his production renders it a decoration first and foremost. A prop to accompany his theatrics.

Ditto for a harmonica substituting as a pitch pipe. That he utilizes a harmonica over a formal pitch pipe indicates a shaky authority, of sorts—he’s no actual seasoned professional, and just uses what he has lying around, but the decision to use it at all sheds light onto his motives and how he conducts himself.

The first note out of his mouth immediately tells us all we need to know about who he is and what he is. Nasal, pinched, and proudly off-key, it cements the notion that his histrionics are purely transparent. Like us, he’s just some guy—some guy who wants to get his kicks for the night and has drafted Porky as his target.

Excessive throat clearing and coughing ensues; it requires a handful of blows into the harmonica for him to settle into the elusive E note he’s been hunting for. Freleng and Stalling’s combined musical direction—or lack thereof—strengthens the setup greatly. By halting any music until he’s finally settled into certainty, his warming up is made all the more obnoxious. He can’t hide behind the benefit of a backing track. Caricatured as his theatrics are, a naturalism lingers behind it—no matter how deep his planning goes to single out a house, grab a music stand and determine his desired musical selections, the spontaneity of spotty vocal training prevails. Expectation doesn’t exactly equate to reality. Not for him, at least; the audience is clued into the notion from the very beginning that his pursuits will lead to nothing but obnoxiousness.

20 seconds after he first enlisted in his music stand, the cat is now formally prepared. The moonlit backdrop behind him doubles as a stage spotlight, proudly illuminating him and providing an unequivocal frame for the audience’s eye to be attracted. All the more attention is thusly delegated to him as he formally engages in his first selection: The Barber of Seville’s Largo al factotum—a Freleng favorite.

Gil Turner is the chosen purveyor of the cat’s animation. His handle on construction may not be as solid as some of his other contemporaries in the Freleng unit, but the loose vivaciousness so native to his work proves helpful in giving the cat a flighty, casual energy supported through his vocals. Such restlessness fits him well.

A quick beat is spared as he takes a moment to analyze the sheet music: another beat rooted in naturalism and believability. Preparation of his stage performance is convenient, but he still has his caveats and lapses and moments of spontaneity. These brief asides of throat clearing and note analyzing and page fumbling reassure the audience that he isn’t an invincible, inescapable antagonist that Porky will soon be powerless against. Enigmatic introduction and quirks aside, he’s just a regular Joe Shmoe. Perhaps that’s why he’s so obstreperous.

Incessant “la-la-la-lalala la-la-la-lalala”-ing proves satisfactory to rouse Porky from his slumber. Rather than demonstrating the process of him waking up, indulging in a surprised take and rushing over to his window, Freleng instead opts to position the camera outside of his bedroom window. That air of intimacy and sense of polite intrusion transfers over from the opening—the cat has destroyed a good helping of those boundaries and rendered any intrusions more casual, but the audience is still inclined to cling to their manners. Eager as the cat may be to invade Porky’s privacy and disrupt his routine, a reluctance lingers on behalf of the viewer. Such gives the audience a stance of neutrality in this moment that is calculatingly arranged through the directing. For the purposes served in this moment, we are an observer first and foremost.

As to be somewhat expected, Porky’s demands for the cat to “g’wan,” go unreciprocated. As do the various instruments he utilizes in hopes of removing the cat by force. Freleng’s musical touch comes in handy once more, as each “figaro” from the cat is uttered in tandem with each household object whizzing past his head. He may not be able to hurl anything back at Porky, but he can at least utilize his singing as its own offensive weapon. An indication that he won’t stop until absolutely necessary.Absolutely necessary manifests in the form of a vase. While the audience has largely been instructed to take a stance of neutrality, a quick shot of the vase whizzing into the foreground of the camera momentarily shunts the viewer into the shoes of the cat. Having this giant porcelain object narrowly rush right past them concocts an argument justifying the cat’s flinching and hesitance in his own responses—to get hit with that would do some damage. The threat imposed by the vase is greater when the audience is able to share a taste of that danger.

Throwing charades are conducted entirely in silence. (Well, discounting the cat’s “singing”, of course.) Stalling suspending his musical score yet again furthers the sense of finality with the show being over. No matter how subtle, maintaining a backing orchestration would imply that the performance lingers. Freleng aims for dubiousness—especially upon the introduction of the vase. Our star cat proves to be persistent, but he isn’t invincible; to keep the audience guessing as to whether he will or won’t stop, whether he will or won’t get hit, keeps the action and stakes at hand all the more engaging.

Especially seeing as the vase adopts a life of its own to further such a mission. Instead of hitting the cat head on or missing him entirely, it remains suspended in the air, aiming itself at his every movement. Vibrations in the vase indicate a pent up kinetic energy that is dying to be released at any second. Thus, once more, the cat’s flinching and cautious observation of this metaphorical bomb is completely justified.

Ballsy, the cat attempts to test the waters. For every “figaro” that is uttered, the pottery threatens to launch itself. Each delivery from the cat is spoken (as opposed to sung), conveying a slight hesitance on the vase’s part. Singing = impact. Speak singing = threat of impact.

Nevertheless, the cat is able to dodge the vase with one final “Figaro!”, firmly propelling it off screen. A laden, tense beat persists after the fact to ensure that the pottery is firmly out of sight…

…allowing the cat to proudly finish his chorus. Musical orchestrations make a triumphant resumption. Cat: 1, Porky: 0.

Vase: 1.

In all, the routine is a proudly mischievous addition that maintains a tonal lightheartedness and even neutrality—this won’t be the case for the entirety of the cartoon. Audiences of 1941 have wet their palates with dozens of cartoons depicting irate cat owners throwing shoes and various items to forcefully pacify any yowling felines—how many have featured an extended tangent where one of said items adopts sentience and proudly dismantles the very set of rules established for it to thrive?

Porky’s Badtime Story features a somewhat synonymous tangent, in that one shoe thrown by Porky is reciprocated by a dozen in return. It’s a polite improbability, but demonstrating the actual sentience of the vase here proves to be a great strength. The sequence revels in its abstractness and improbability. There is no rhyme or reason to it, no justification for the vase’s absurd physics. Confidence dominates this proud surrealism, which is the best possible recipe for its success. It should be noted that in each respective remake of this and Badtime Story, both “impossible tangents” are shed.

“Theh-thee-thehh-that’ll teach you t' eh-keep quiet,” grouses Porky, who now is as much of an observer as we are. His wording implies that he has full control over the impossible physics of the vase, and wasn’t just spectating in tense, perhaps clueless anticipation as to whether or not the impact would land. In spite of his demotion from aggressor to spectator, he’s still quick on the draw to assert his superiority and make a point that the cat isn’t wanted. The slight up angle in which the house is arranged subliminally furthers said authority throughout this exchange.

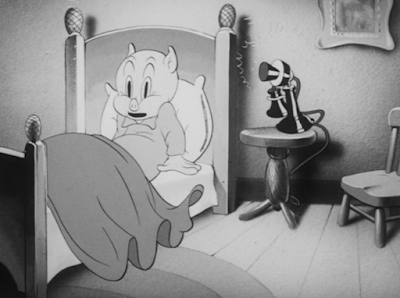

With matters resolved, Freleng and Porky indulge in a book-end to the very beginning of the short. Shade down, pig obstructed by a silhouette, desires of getting some shut-eye plainly expressed.

Yet, unlike the opening, the camera resists the impulse to cut to Porky’s bedroom. Instead, his bedroom window remains in view: such indicates to the audience that an interruption is brewing off-screen. Freleng’s stolidity in direction proves helpful in furthering anticipation; he trusts that the audience is able to read between the lines and piece the appropriate context clues together. He doesn’t insult their intelligence by laying out every little action. No cut of Porky getting back into bed. No cut of the cat climbing back up the fence.

Instead, mere audio cues are all he needs. Audiences are made acutely aware of the cat’s return through the loud-n-proud resumption of another chorus (“When Irish Eyes Are Smiling”), just as they are clued to Porky’s brewing frustration from the click of the light.

Little relevance is fostered with Porky reappearing in the window other than technical obligations: to indicate that Porky is awake and irate, and to offer a coherent transfer of ideas as the camera leads us into the security of his bedroom. Thus, the seal of neutrality is broken: the following handful of minutes place an emphasis on Porky, whether it be his attempts to get rid of the cat or to finally get some sleep. A caveat, of course, being that the two are frequently contested against one another.

Where vases and shoes have failed before, Porky indulges in age old adage: throwing the book at him. Animated handiwork has since turned into that of Dick Bickenbach’s—typical with his work, his proficiency in various skills (solid animation, believable character acting, tactical impacts and a powerful sense of speed) continues to make him a necessary asset to Freleng’s unit. Interestingly, Porky is handled with some shadows that seldom appear in any forthcoming scenes. Such makes his environments seem all the more interactive and dimensional by demonstrating how his shadow is projected against the window, the wall, etc. That sense of grounding in itself furthers a subliminal empathy on his behalf.

Even if he is violently clobbering cats with books and vases, hinting at an impending case of retaliation. Once again, Freleng trusts the audience to put the pieces together by depicting the collision entirely through audio cues. Porky throws the book, a combined smack and strained yowl are heaved in response, and the audience notes a conspicuous lack of “When Irish Eyes Are Smiling”.

Porky rubbing his hands together is an act that reads of a lighthearted conceit all its own. His “Tehh-take that, you old cat,” bears enough finality in its wording for the cat to take the hint, but the addition of contemptuous hand rubbing—as if the book has been so tainted just by entertaining the idea of making contact with the cat—renders his defensiveness a sort of act all its own. As if he can’t truly dispose of the cat without the added security of such a gesture.

An impending case of retaliation is no longer impending: it just is. Pop culture historians may be intrigued to note that “The Return of [Dr.] Fu Manchu” is indeed a real book (and not just a topper concocted for the benefit of this short) that was likewise adapted into film in 1930; At the time this short was released, 8 Dr. Fu Manchu movies had been produced—8 more would follow after a 12 year hiatus. Audiences viewing this cartoon may have been inclined to recognize the movie reference through the book more than the reality of it originating as a book itself.

Of course, all of this is completely irrelevant to Porky, who is not pondering the semantics of what he got hit with—just the principle that he got hit back at all. Befuddled, ruminative blinks as he struggles to makes sense of what happened give him a subliminal endearment and sympathy. Outrageous asides offered by the film are rejuvenated when juxtaposed against slower, grounded beats; the intended impact of the gag wouldn’t have registered as strongly if Porky had immediately gotten to his feet. Porky especially is a character who excels at these candid, contemplative moments. His casting in this short absolutely works to its favor.

A return of the book is of course amusing, but topped completely through the cat’s dramatic resumption of his chorus off-screen. The orchestra swells as he approaches the grand finale—an indication that each act of vengeance from Porky will only be met with a more forceful display of theatrics.

Accentuating that irate dismissal, the window Porky forcefully slams shut maintains a momentary glare in the inking. It very well could be an animation error, but that brief increase in opacity gives the impact a physical tangibility.

With that firmly taken care of, Porky heads off to bed—only not nearly as contented to resign himself as he once was. Another strength of the short is thusly enacted. Throughout the duration of the cartoon, Porky’s patience with the cat—justifiably—lessens and lessens. His frustration has been noted starting with the very first interaction with the cat, but the audience is able to see how he grows more and more worn down, more and more aggrieved. A real sense of emotional progression ensues, which strengthens the identity and solidity of the short. Porky isn’t just a prop for the cat to act against. Both of them feed off of each other’s actions, motives, and intents in a continuous loop, forming a product that remains engaging and entertaining through such a calculated balance.

Much of the short’s entertainment value is, likewise, sourced from the little details that support the aforementioned observations. For example, Porky’s near incomprehensible grumbling under his breath as he stalks away. Riding on the trend of this cartoon offering a comparatively candid perspective, the execution feels so spontaneous that it almost seems erroneous. That the dialogue was inserted at all indicated a purpose—same with the lack of musical orchestration, the muttering and grousing in silence reading naturally and intimately.

Conversely, a lack of lip sync creates an inherent disconnect between the audio and what’s on screen. For example, Porky’s dialogue continues for a few seconds after the animation has indicated he’s gone back to sleep. It isn’t necessarily a fault, as, against all odds, Freleng still somehow manages to pull it off—if anything, it reads exceedingly Fleischer-esque, synonymous with the ad-libbed muttering that graced so many a short with Popeye’s name on it. Mike Maltese was a writer for Fleischer.

Regardless of intent or approach, the candidness of Porky’s grousing is a joy. It supports the feeling that the audience has caught him in a scenario (or, in this moment, a mood) he hasn’t intended for anyone else to catch. Perhaps this is a glimpse at what the true Porky Pig is like, once he’s finished his daily shift of posing for title cards or bursting out of hollow drums. Organicism in Blanc’s deliveries (“Eh-jeh-jee-gee whiz, I’ll eh-beh-be-ehh-beh-be a nervous wreck if ee-the-ih-this keeps up, I eh-geh-ge-eh-geh-gotta get some sleep, eh-theh...yeah...”) unites everything together. A powerful sense of intimacy prevails that has seldom been utilized so effectively in association with Porky before.

The phone at his bedside isn’t an addition to make the environments feel more lived in. Once more, just as he’s barely begun to flirt with the idea of getting some sleep, the harsh ring of the phone violently rips that sanctuary away.

Freleng continually exercises a great display of restraint: throughout this time elapsed, ever since he first slammed the window shut, no orchestration has lingered in the background. Not even the drone of a single note held out. This complete suspension of sound, this almost stuffy sense of silence provides the atmosphere with a stillness and sleepiness that justifies Porky’s own quickness to fall asleep. It moreover maintains all of the aforementioned observations regarding the intimacy and naturalism in this moment.

Porky’s answering of the phone maintains that believability further. His “Yee-yee-y-yes…?” is burdened by his own weariness, but s nevertheless registers as an attempt to be presentable. A great contrast against the candor of his aggrieved mutterings moments prior, it supports the earlier argument that we are spying on a Porky not often presented to the public. His attempts to make pleasantries over the phone is more in line with what we—and he—are used to. Not to imply that every Porky cartoon up until this point has been a result of him putting on a hollow façade, as that is vastly far from the truth. Just a reminder of how this short utilizes its somewhat enigmatic intimacy to its advantage.

Even with all of this in mind, Porky can’t help but drift off on the phone. Freleng makes a continued point to stress just how tired he is all throughout the short: thus, the all too inevitable awakenings and heckling from the cat registers more harshly. Likewise, Porky’s fraying nerves are warranted all the more. There’s a continued consciousness all throughout the short regarding everything must be handled; obviously, such is a director’s job, but this sensation of carefully crafted string pulling and awareness as to how each action feeds into another is very compelling here.

Especially since having Porky entertain the idea of falling back asleep proves to be yet another aspect of the cat’s plan. After he answers the phone, a comparatively long beat of silence persists. Enough to support his nodding off. Seeming to sense this, the cat waits a beat before finishing his chorus with one last “A-WAAAAAAAAAAY!” over the phone. The resumption of the musical chorus in the background ties the entire charade all together, giving the finale a sense of earned grandeur. Earned for the cat and the audience, who has subliminally been anticipating such an outcome, anyway. Drawn lines to give indication to the sound further the tangibility in his performance.

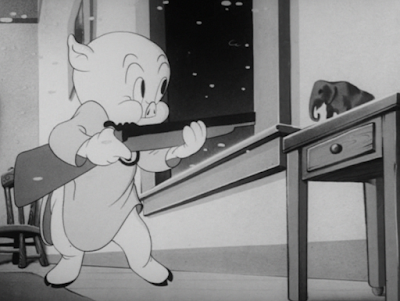

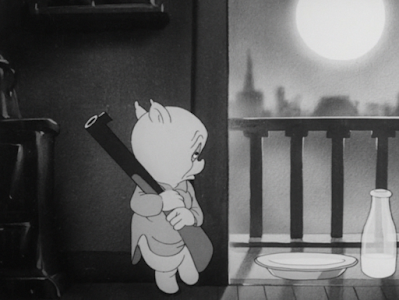

Thankfully, Porky has an age-old mantra to abide by in these trying times: if you can’t beat ‘em, shoot ‘em.

Such a blunt solution arguably opens up a floodgate of nuances regarding the short’s chemistry. No matter how much of a nuisance the cat may be (which he undeniably is), pulling a gun on him with the intent to kill arrives at an extreme. Thus, the audience may be somewhat more sympathetic to the cat’s decision to keep heckling Porky, since it’s his own means of self defense.

The story would be somewhat different—as well as less engaging and funny—if Porky was completely powerless against him, but this introduction of a threat, no matter how extreme it may seem for such an amusingly warped scenario, offers a bit of leverage to ensure that the audience isn’t blindly rooting for Porky the whole time. Of course we’d like for him to get some sleep, but we’d like to see how the cat counters this even more. Especially when his countering is now comparatively justified with a threat involved. An eye for an eye, a gun for a song.

So, rather of following Porky’s antics as he aimlessly chases the cat around with a loaded rifle, we instead follow a more calculated—and less physically taxing—means of hunting: luring the cat in with a fresh bowl of milk. This, too, could be interpreted as a loose inverse to the cat’s methods of heckling. Where the cat often deludes Porky into believing he can catch a wink of sleep (only to burst in and disrupt him at the last possible moment for the most efficient interruption), Porky does the same: trick the cat through false niceties rather than just gunning him down directly. It’s a smart move for Porky, since chasing the cat with a gun directly doesn’t seem like it would yield efficient results in his current state. It moreover offers a greater display of cruelty by hiding behind such façades. This, again, feeds into the aforementioned justifications—no matter how loose the term—with the cat’s heckling.

Notes to You is a short who utilizes its monochromatic limits to its utmost advantage. Limited to a mere palette of black and white, Freleng and his background artist, Lenard Kester, are forced to get creative in their careful construction of a sleepy, nighttime atmosphere. Much of this is accomplished through a strong distribution of values—the shining full moon that dominates nearly every shot of the night sky is the greatest example of this. It bathes the environments in an ethereal, milky light that enables the backgrounds to breathe and thrive. The night sky is more than a stock backdrop haphazardly dropped in for the sake of obligation. It’s a strong, dominant atmosphere that can be as cozy as it is empty and perhaps even chilling.

Milkiness of the sky offers a palpable contrast to the dark shadows dominating the interior of Porky’s house. Not only are the backgrounds legible through these contrasts and thusly made engaging visually, but they likewise construct a physical parallel. Porky’s half of the screen, where he’s framed by the security of his dark home interior, and the half of the screen intended for the cat, exposed through the bright glare of the moon.

A priority of these dreamlike backgrounds is, of course, to instill a sleepy atmosphere that once again legitimizes Porky’s own drowsiness. His plan is well thought out: cats like milk, catch him while his guard is down, keep the lights off in the house to give the illusion that nobody is there, etc. However, one key hook has drastically been overlooked in the process—Porky himself can’t even keep his eyes open long enough to see his own plan through.

Freleng’s handling of Porky’s somnolence is incredibly handled—a compliment that applies to the entirety of the film throughout. A lesser director may have used this opportunity to poke fun at Porky, implying that he’s to be viewed as a powerless stooge and is to be patronized for his helplessness. Of course, there is a lighthearted, endearing sentiment throughout that will be reflected more explicitly later on, but the directing makes a point to sympathize with him. Not pity him into condescension, but to relate. For example, Stalling’s music score wilts in tandem with Porky to, once again, provide a tangibility that the audience can feel.

Mel Blanc’s deliveries are likewise integral, remaining understated and handled with a certain softness/weakness (especially in more vulnerable moments like these as Porky is actually in the process of falling asleep on screen) that still remains relatively new to his approach with the character, who tends to speak in statements rather than fully nuanced fluctuations. Those would begin to develop more steadily in coming years.

To say Porky speaks in statements sounds like a completely bogus observation, given that everyone speaks in statements. However, the auditory fluff of his stutter often gets in the way of how his speech patterns are interpreted; even removing the stutter, he still structures his sentences and conducts himself in a manner unique to himself, just like any character. Up until this point, his sentences are often cultivated with a motivated, perhaps even brusque sensibility. The smiley vacancy he is often prone to have (in the Clampett cartoons especially), that sort of oblivious, well meaning and often accidental condescension is very much reflected in the comparative boldness of how he talks. Compare his syntax to someone like Daffy, whose speech is fluffy through repetitions, tangents, random self-interruptions, speaking in idioms or allusions or metaphors, etc. Porky’s speech is much more bold and to the point in comparison: it just never receives as much thought since his stutter is always the immediate takeaway.

All of this long winded syntax about syntax is meant to applaud Freleng’s nuances in this cartoon; that’s why Porky muttering under his breath as he stalks off to bed is so noteworthy in its comparative candidness. The very same applies to here. There haven’t been many instances where Porky’s voice has trialed off or been conducted with the same gentility and organicism here. It may seem menial to comment on (of course his voice is going to trail off if he’s falling asleep), but it’s just as important of an aspect as any in furthering the immersion of this cartoon. Good on Freleng for making such considerations.

If it’s any consolation to Porky, his plan of luring the cat nevertheless proves successful. A shot of the cat cautiously—if not somewhat pretentiously—dipping his index finger into the saucer is shot through the doorframe enclosing the screen. Directorial focus is neutral, in that the audience can’t see the full extent of the cat. We don’t know what he was doing beforehand or where he was lurking, we aren’t sure of the exact expression on his face, etc. This disconnect, no matter how slight, maintains the cat’s status as an enigma that’s always just out of reach. He’s taken the bait, but is still within his own security. His presence lingers here, just as it does throughout the entirety of the cartoon. Even/especially when he isn’t physically on screen.

Obfuscations of the cat’s face don’t prove a hinderance to his expressiveness. Through the stretching of his finger to the excited, motivated raise of the hand, the audience is seamlessly able to gather that he’s tasted the milk and found it to his liking. With the threat of a rifle literally put to sleep, the cat is free to indulge in the remainder of his portions, which he does so willingly. This action again remains off screen, communicated purely through a splashing sound to indicate his drinking. He’s still to remain somewhat oracular… even if he’s no longer required to be cautious in this moment.

As a demonstration of thanks, the cat momentarily assigns Porky the role of his designated milkman. Another great bit of “pretentiousness” that matches his earlier testing of the milk—any normal stray cat licks it up and strolls about his business. Like his getting on the fence, like his preparation of music, like his repeated attempts to remain in Porky’s line of hearing at all times, this, too, is turned into a production.

The underlined emphasis under his “two quarts” is as amusingly ballsy as is his request for grade A milk (as opposed to the comparatively less made-to-consume grade B, which, again, a regular cat would not scrutinize); that Porky left some milk out at all is a charitable gesture in itself… regardless of his intentions behind it. To ask for twice as much—when not expecting this surprise initially—for the next day, implying this entire charade is to be repeated all over again tomorrow, is brilliant in Freleng’s attention to detail and brilliant in the cat’s conceit. On the surface, it’s just a standard milkman gag—however, as has been a faithful mantra throughout the analyses of these shorts, that Freleng allows such room for interpretation is a testament to how engaging and well handled the story and conflict is here.

Animation courtesy of Cal Dalton, the cat pokes his head in the door to confirm his suspicions. The parallel constructed by the split-screen is at its most apparent here, when each character is clearly seen dominating their own corresponding side; somewhat ironic, given that this clarity is initiated through the cat breaking such a boundary. In other words, he confirms Porky’s presence, which confirms more opportunities for further heckling.

Logistics of the cat singing and his performance value aren’t even considered as he violently slams a spoon against the saucer with insulting nonchalance. This is no longer about Porky interrupting his concert or the cat’s operatic catharsis—it’s just him being a nuisance for the sake of being a nuisance.

Even taking such deliberate cruelty into account, it once more proves difficult to arouse unadulterated anger towards him. It’s the Daffy Duck philosophy; he takes clear delight in messing with Porky, and prioritizes the rush of getting his kicks in over the actual intent behind his heckling. There is no greater lesson or moral behind his escapades, no obedience to a grudge. Porky is just his plaything for the night, and he’s going to exhaust every avenue of enjoyment and satisfaction he possibly can. The vendetta harbored by Porky against the cat is once more crystalized through the deliberateness in the cat’s actions, but an impish harmlessness prevails overall.

An impish harmlessness from the cat, anyway—the rifle is quickly reunited into Porky’s grasp once he’s come back to his senses, which signals for the cat to scram.

Attention to detail in Freleng’s direction almost proves to be an inconvenience—it’s an incredibly slight nitpick whose expounding here is moreso to bring attention to the detail at all, rather than lambasting it. Understandably astonished by the deftness in which Porky retrieves his gun, the cat indulges in a surprised take before scrambling off screen. The tin pan in his hand is thusly sent flying in the process. Unfortunately, it all happens so fast that the act of him losing the saucer is lost amidst the visual hubbub.

Eagle-eyed (eared?) Freleng comments on this development by including the sound of the tin pan hitting the ground. All the more power to him, seeing as few directors would take the time to enunciate such a menial action. Environments again are made immersive and dimensional through these considerations, as Freleng ensures that every little action, every little detail, every little impulse has a motive behind it and a subsequent reaction. As astute as this attention to detail may be, the resulting effect is somewhat stilted thanks to the inarticulation of the saucer being thrown. The sound effect is delayed to convey the pan flying through the air and hitting the ground after a short distance, but without the visual information of the pan made exceedingly clear, the end result is just an awkward, aluminum noise aimlessly tacked onto the adjacent scene, cluttering the audience’s ingestion of the new information unfolding on screen.

Attention from the viewer is too preoccupied by the chase moving to a new location to really notice or care, which is why it’s being brought up now. Some of Freleng’s best cartoons are the ones where he’s thinking of the smallest details and how they can enrich the overall product… even if they’re liable to be missed by the audience, or could stand to be a bit smoother in execution. This scrutinization and implementation of detail is representative of a directorial commitment. An investment in how the audience is invited to interact with the cartoon. Notes to You was not something mindlessly churned out to hit a quota.

With the second act of the cartoon underway, Freleng adapts himself to this change in scenery. Stalling’s music score is just as ethereal as the foggy, distant backgrounds—there’s a cold, furtive unease accompanying Porky’s stealthiness that encourages a powerful atmospheric versatility. The moonlit backgrounds that once seemed so cozy and inviting, so optimistic and perhaps even fantastical in their tall shadows and moonbeams are now cold in their stark shadows, mysterious in their foggy depth of field, vulnerable in the moon’s role as an eternal spotlight. Hundreds of “sneaky” music scores have been sourced from Carl Stalling’s pen, but the instrumentation here—given new life through Milt Franklyn’s orchestra—offers a unique sound meant for this very context that seems to have seldom been replicated in other cartoons.

Such powerful implementation of atmosphere is integral for keeping the audience invested and offering a memorable voice this cartoon can call its own. On the other hand, it proves just as helpful in its own self destruction: the eerie stillness of the backgrounds, the creeping chill of the music, the steely determination in which Porky conducts himself with the intent to kill are joyously undermined through one of Freleng’s favorite pet gags: two characters running on either side of a fence in perfect tandem, unknowingly exposed to each other through a sudden lapse in wood. The Freleng Fence.

As far as humor goes, it may seem unremarkable now. Other cartoons would find different avenues to make it read more flashy or subversive (Ain’t That Ducky comes to mind, where Daffy—seemingly gliding along in mid-air, pensively perusing the dailies, dismissively pulls a curtain over the top of the fence once he realizes he’s been exposed), but the visual itself here isn’t so much a priority as is the way it’s conducted. A fence disappearing into nothingness isn’t exactly funny, but Porky running along on his tiptoes with such an indulgently conniving expression, music considerably more juvenile and sprightly to match his tinkering steps—all completely disestablishing the tense, moody atmosphere—most certainly is. Contrast conducts comedy, and here, said contrast is exceedingly clear.

Comedy is, likewise, almost always delivered in threes, to which this is no exception. Each contemplative halt before the eventual run past the fence—Porky flicking his eyes back and forth, coming to a stop, even Stalling’s music making a point to put on the brakes—is just as integral to the rhythm of the gag as the entire sequence itself is. Somewhat ironic, seeing as it is ever so slightly intended to break up the flow through these sudden stops. It’s a fun, lighthearted, politely asinine aside that doesn’t detract from the suspense of the story—only pokes slight fun at it. This is all over a singing cat.

These furtive theatrics all amount to one of the most visually ambitious maneuvers of the film. Orchestrated from the cat’s point of view, the fence is animated to turn in tandem with the cat as he pokes his head around the other side, giving the illusion of the camera following his movements and encouraging a palpable sense of depth. A static color card lingers beneath the animated elements—the camera is positioned at an angle that eliminates the need for extraneous background details that also would have been taken into account for the turn, lessening the workflow (and room for error by proxy.) Instead, all eyes are on the cat.

And on Porky stuffing a gun in his face from the other side, of course.

Perspective isn’t the only aspect subject to change through the dramatic shift: demeanor, too, as the cat is much less self-assured and amiable when he finds a gun thrust in his face. Freleng times the rotation with a discernible ease in and out; such offers a powerful weight and drag to the motion, offering a tangible beat of start and stop that the audience can physically feel themselves. Consequently, Porky’s sudden appearance is amplified all the more. The camera explicitly follows the cat’s point of view rather than Porky’s, so that the endangerment prompted by the rifle is taken as a larger threat. We see and feel what the cat sees and feels—a continued necessity to offer balance to the dynamic and ensure that the short isn’t complete one-sided. Porky’s gun isn’t just a prop for him to run around with. Its barrel is loaded with lethal consequences.

“Neh-neeh-now I gotcha an' I’m gonna buh-be-buh-be-ehh-blow your head off!” confirms these notions. If it hasn’t been made clear through the four minutes leading up to this moment, Maltese and Freleng approach Porky with a cynicism and even brutality that has very seldom been in association with his character prior. If so, they have been executed in short flash bangs. The ‘40s would see the rise of an abrasive, cynical, and reactive pig, but it’s very much owed to shorts such as these that makes that the case. This may not seem like surprising behavior for those of us who are acquainted with Porky’s filmography, observing as he wields axes and rifles and expends synonymous threats quite liberally (in Bob McKimson’s cartoons especially), but, at this point in 1941, that was a rather anarchic take with the character. Porky’s Bear Facts—Maltese’s first outing with the character—demonstrates hints of this behavior, but it isn’t necessarily until here that it’s fully realized. The same applies to My Favorite Duck, which is regarded as a passing of the torch in numerous respects. Maltese is likewise responsible for the writing in that cartoon.

Notes to You is often seen as the lesser entry against its remake, its comparatively leisurely pace often being a factor. Indeed, Back Alley Oproar sets a new precedent in itself for its breakneck pacing, but the directorial rumination in Notes yields its own unique benefits. For example: offering a beat that allows the audience to see the gears turning in the heads of the characters.

As is the case with the cornered cat, whose expression of fear is now rooted in sincerity. With Porky pushing him up against the house, the cat spares a handful of sporadic turns of the head, clearly attempting to formulate a last minute plan of some kind. Not dissimilar to Bugs Bunny cartoons of this era, this brief break in composure ensures that, enigmatic as the cat may be, he digests and processes information like the rest of us. He can be caught off guard, he can be found in a moment of weakness. The audience of course expects him to find a way to triumph, seeing as there’s still half of a cartoon to run through, but these momentary lapses and displays of vulnerability strive to keep the stakes engaging. Entirely favoring one side over the other wasn’t to Freleng’s directorial advantage in this particular cartoon.

Admittedly, handling of the cat coming to a realization could stand to be a bit more stable, but such a deduction is once again a result of purposeful scrutiny rather than a major deterrent. Demonstrating the cat’s thinking eats up a slight beat of time—an obvious consequence, of course, but is made most notable through the awkward, idle animation on Porky. If he had remained in the same position with his gun pointed and scowl intact, the pause would have worked without any issue. Instead, the animator pays attention to Porky’s role in the equation and depicts him reacting (or, at the very least, losing his scowl in favor of nonplussed vacancy) to the cat’s reactions, which induces some unintentional visual clutter. Focus is nevertheless favorable to the cat over Porky; it’s an incredibly minor distraction when all is said and done.

Especially given that the major distraction from the cat is what audiences are expected to turn their attention towards. Whereas he once used his vocal chords to antagonize Porky and keep him awake, he now practices the opposite: singing a lullaby in expectation that Porky will be pacified, and he himself will have a verifiable means of escape.

Once more, the performance is beautifully—and, most importantly—hilariously articulated, largely thanks to Blanc’s shared performance between the cat and Porky. His wispy falsetto of “Rock-a-bye Baby” revels in its own patronization and disingenuousness. Cloying saccharinity on behalf of the cat is intentionally subject to laughter, but doesn’t undermine its own intent, either. Once more, Porky isn’t intended to be shamed for his quickness to fall asleep. Rather, playfully pitied (which, even then, “pity” carries too pathetic and negative of a connotation for this to really be the case.) Stalling’s backing orchestrations are fluffy and light, but armed with enough conviction to again warrant Porky’s condition—the music isn’t comedic or seeking to chide him. The audience is encouraged to chuckle and smirk at how effective this “cop-out” of a plan is, but not necessarily at Porky’s expense.

Much of this can be owed to Porky’s own indignation towards the cat’s doings, who is as wise to his insincerity as we are. Stalling’s treacly melodies adjacent to Porky’s low, petulant mutterings of “Eh-neh-now stop it,” could not be any more well directed. Once more, Freleng prevails with his directorial excellence by stressing that less is more. He presents two parallels for the audience to delight in all themselves, resisting the urge to spoon-feed information or play the performance up to an accidental degree of insincerity.

Part of what renders this scene so captivating is that Porky’s stubbornness is so clear: he really does not want to fall asleep, and is wise to the cat weaponizing his fatigue, but just can’t help himself. It’s more endearing to watch him put up an active fight against the cat (futile as both he and the audience know it to be) than to see him submit without a word. His expressed awareness to the cat’s doings makes the encounter all the more dimensional and intriguing—there’s a greater sense of conflict than if he happened to be caught off guard completely and remained oblivious to the cat’s intention.

The conflict is what sells it. Conflict between Porky and the cat, but directorial conflict and even self-conflict: he completely wilts on screen, curling up on the ground with his rifle notably in hand, but continues to argue the entire way through. So much so that the only reason he stops arguing for the cat to “ck-ck-eh-quit that” and “now, don’t…” is because he’s asleep before he even has a chance to say the rest.

Again, Blanc’s deliveries are masterfully approached with a gentility and consciousness that Porky has seldom been privy to. One gets the sense that his stuttering on “Ehn-neh-neh-eh-neh-no-now-now-now, stop...” isn’t a product of a speech impediment, but him losing a handle on his words as a result of his own fatigue. Even a subtle voice crack finds ekes its way in through the aforementioned delivery, exacerbating this sense of losing control of his metaphorical and literal voice. All of that in tandem with Cal Dalton’s slow, gradual, almost molasses animation of Porky crumpling to the ground make for an incredible end result that flourishes against the persisting lullaby. The cat doesn’t need to argue “No, I won’t stop,” back—maintaining the music without a single break expresses this sentiment just the same.

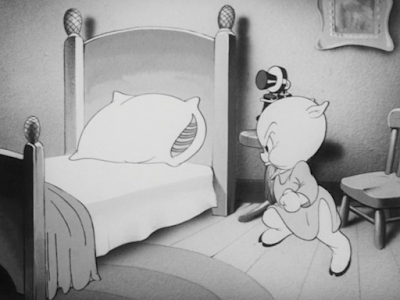

With Porky incontestably defused, the cat utilizes this opportunity not to flee and save his hide, but continually coddle Porky. Freleng embraces the obsequious allusion of a mother escorting her toddler to bed; before scooping Porky into his arms, the cat affectionately chides him with innocent patronization: “Poor dear.”

Comparisons of escorting a young child to bed are furthered through the abandonment of his gun, which is left behind with the same nonchalance that would be the case if a kid had fallen asleep playing with his toys. This is of course funny in these particular circumstances, given that Porky’s gun is a raging antithesis to the endearing domesticity of a child’s plaything.

Freleng caps the entire charade by encouraging Stalling’s music score to fade out. Gentle, wispy humming from the cat takes precedence as he carries Porky back inside—it’s the same directorial philosophy reflected in Porky’s begrudging mutterings as he stalked off to bed in that a lack of music induces a believability and immersion to the environments. There isn’t that subconscious separation, that spectatorship offered by tacking a musical arrangement on top of the action. Instead, the audience is in the action. Freleng’s conscientiousness is really in top form.

Thoroughly incapacitated, Porky is put to bed. Cloying as the cat’s actions may be—topped here by tucking Porky into bed and planting a kiss on his forehead—the audience is almost led to question whether the cat’s had a change of heart. After all, his heckling is entirely based on a desire to self entertain and stimulate. He isn’t actually out to drive Porky mad so much as he just needs to get his kicks in; perhaps he’s met his quota for the evening and knows not to push his luck any further. What could he possibly gain by doing all of this?

As he tiptoes out of the screen, the camera expends just a few more seconds of focus on Porky, lulling both him and the audience into a false sense of security. Stalling’s music still remains repressed as the viewer is somewhat inclined to question the organicism of the sleepy atmosphere…

Which is violently disrupted through the brash, marching band adjacent orchestrations of “Frat” that erupts with a cacophonous bang. Such answers earlier questions on the cat’s motives: the privilege of gaining entry into Porky’s home. Narrative sympathies take Porky’s side yet again as they share his complete bewilderment and shock as he jumps awake, clearly unsuspecting of such a serenade. Viewers are somewhat more expecting of this surprise than he is, but Freleng’s restraint regarding the reveal—allowing the music to blare for a few bars instead of immediately cutting to what the source of the music is—keeps them guessing just as much as Porky. The quest to discover where the music is coming from is unanimous between pig and theatergoer.

A stolid camera cut provides our answer. Synonymous to his rapid banging of the spoon against the milk pan, the cat’s utilization of the radio indicates that his mission to keep Porky up and fray his nerves isn’t entirely reliant on his own vocal chords. One loud noise is as good as any. To a lesser extent, such is a precaution on behalf of Freleng (and Maltese’s writing, too); the cartoon would grow much more stale if the cat’s only means of heckling was derived from singing the same selection of songs the same way every time. Fleeting as this aside may be, its novelty induces variety, which induces engagement and interest.

Fervent histrionics channeling that of a frantic conductor remind the audience that the cat, at the end of the day, is the orchestrator of such hijinks. He may not physically be conducting the cornpone marching band through the radio waves, but he is responsible for weaponizing their music against Porky. His actions reek of a self satisfied juvenility that supports earlier arguments expressing his desire to get his kicks for the evening. “Inconsiderate” is too mild a word to describe him, but, even in spite of Porky’s aggrieved reactions and intents, is largely harmless in his own intent at the end of the day. That sort of innocence—if one were inclined to label the cat as such—is touted in this moment.

Interestingly, when the music comes to a stop, the cat turns his direction to the camera rather than Porky at screen left. That audience awareness again makes a case for the overwhelming tone of playfulness; it’s a concession, a coy acknowledgment of his doings, a subliminal conveyance of “ain’t I a stinker”. The viewer is made to feel as though they are in on the joke, that they are aware the cat is aware. Thus rendering him somewhat more likable. Or, at the very least, a bit more than filling an obligatory niche of “nameless heckler to give Porky something to react to.”

Said concession likewise hints to further impishness: just because the music has dropped out doesn’t mean that he’s finished with his play-orchestra. Freleng collaborated with Stalling yet again to fake the audience out with a deceptive snatch of silence—a four note coda à la Al Jolson’s “good evening, friieeeends” is tacked on for maximum obnoxiousness on behalf of the cat. Just as the audience thinks he’s done, he’s always got something more to edge further. This goes doubly for the finality of a drum cymbal after the coda, which, likewise, lingers after a slight beat. Freleng masterfully times the joke(s) to feel intentional in their fake-out rather than a slog of added annoyances. He and the cat duly succeed in their quest to pester, but not at the expense of the film’s quality or coherence.

One final bow in stuffy silence indicate that the cat has now fulfilled his obligations with the radio.

Especially when the abrasive sting of Stalling’s music cuts in. This isn’t a case of him adding a tangible source of music to taunt Porky further, but him stepping back into what he does best: representing the emotions and motives of the characters. An abrasive, sharp sting matches the surprise take from the cat, indicating that business is about to resume as normal.

A close-up shot of an oncoming porcine asserts as such. Freleng hints at such an outcome through the cat’s deliberate testing of both the audience and Porky’s nerves—with Porky now awake, something has to come out of it. Still, directorial restraint allows the reveal to maintain a surprise aspect (a common theme throughout this short that works to its strengths.) We know Porky is going to chase after him, but we don’t know exactly when or how. Audiences digest this new information at the same exact time as the cat, momentarily shifting narrative focus and perspective back onto him. All part of the metaphorical hockey match established in this short’s structure, constantly diverting its attention to both characters when the context is right.

Our star feline is bawdy, but not stupid: the endearingly crude grimace on Porky’s face is not to be tampered with. Escape takes precedence.

Still, this, too, is not permanent. Brevity in which the cat rushes out of Porky’s room and the ease in which Porky is able to deadbolt the door shut without interruption arouses suspicion. If this short has taught us anything, it’s that these moments of leisure and solitude are not to be taken at face value. A catch is always lingering nearby.

Outside the bedroom window, to name an example. Dick Bickenbach assumes animation duties, tackling both Porky’s befuddled reactions to the noise outside and the familiar source of said noise—lines emitted both from his shocked takes and the impact of locking the keys are a dead giveaway of his work.

Hinted through the usage of “Frat” on the radio, the cat’s medley of songs have now adopted a moderately contemporary tone. At least enough to distinguish the selection of songs from the highbrow articulations of prior operettas: “The Umbrella Man” is no work of Rossini’s. For fans of Mel Blanc’s singing (hopefully all of you), it’s better. As a brief candid aside, his performance of this song is my favorite out of the entire cartoon. It strikes the perfect hint of annoyance so perilous to Porky’s nerves, but is rife with a warm, amiable, if not hammy charm that almost begs to be realized into a full length accompaniment.

Perhaps Bickenback’s animation fitting so well with the vocal and musical accompaniment is owed to that. Not that the success of Blanc’s vocals is reliant on how proficient the animation is (often the opposite, as particularly lesser animation may force the viewer to pay more attention to the sound and divert their praises there), but a worthy vessel to give his performance life, to have it pour out of a character’s intents and motivations—even a nameless cat’s—is not to be taken for granted.

That the cat takes the time to arm himself with a prop could be another factor in the scene’s likability and memorability as well. Not even a regular household umbrella, but a dinky little prop that explicitly connotes performance and extravagance. Like the music stand, these extra preparations and sense of purpose behind such props really ties the cat’s motivations together. None of this is a result of pure happenstance.

Freleng’s staging of this particular footnote again proves to have its own motivations. Framing the cat through the window induces a separation of sorts, encouraging an indication that he is far out of reach from Porky inside, which only exacerbates his frustration further. Likewise, the audience is again placed into Porky’s perspective, receiving the same dosage of annoyance that he is. We see what he is seeing. And, on a narratively neutral note, much of the background is comprised of a blank color card. Such directly shunts the cat into the spotlight. The fence is raised high enough to conceivably obstruct the implied horizon line, allowing such details as a skyline and grass to be feasibly cheated, but the excision of trees or the moon and other visual decorations ensures that the cat takes precedence first and foremost. There are no frills: just the ones indicated by his singing theatrics.

Another benefit of the window as a staging device: a means to physically enunciate Porky’s frustrations. There’s a great irony to be had in that his aggrieved closing of the window and curtains is as musical as the cat’s performance. Once more, Freleng is able to milk his musical and behavioral timing from all ends, creating a rich and motivated result in the process. Porky’s silence and a lack of a discernible facial expression prove to be no obstacle; the metaphorical and physical closure of the window and the aggression in which he dies speak more than words or even a scowl ever could.

Instead, other avenues of sympathy on his behalf are explored. Lessening the pauses between acts and inflating the cat’s persistence encourages the audience to experience the same overwhelming blend of non-stop cacophony that Porky is currently being subjected to.

Our current selection of cacophony is a demure, nasal selection of “Jeepers Creepers”, which is a score well acquainted with Stalling. To make this happen requires some suspension of belief regarding the geography of Porky’s house; with Porky established to be glaring out of his bedroom window, the camera cuts to the front door of the house opening, to which Porky turns to and scowls. Such seems to imply that the front door is also in his bedroom—particularly through the availability in which Porky is able to thrust his entire body against the door to barricade it shut.

That this is the short’s weakest moment in its directing says something about the quality of the short otherwise. Particularly since there almost seems to be an air of purpose behind it. The audience isn’t intended to be concerned with every square inch of Porky’s floor plan and what relates to where—selling the idea of the cat’s omnipresence is much more important. It’s as though the cat is so available, so trigger happy, so eager to heckle Porky with another song that it’s completely irrelevant how that is achieved, as long as it is achieved. This breach in convention works in his favor and supports Porky’s frustration all the more. His invasiveness now extends to completely dissolving boundaries and simple geography of the house.

With the closure of Porky’s door comes the closure of both the cat’s singing and Stalling’s music score yet again. Such fleeting moments of silence—and relief, on Porky’s part—are enunciated further through the repeated on and off of the music. It offers an alternative, an example what could be going on without the annoyance of the cat lingering nearby. A piece of sanctuary that inflates the obnoxiousness of the cat when he’s all too quick to destroy it again.

Which is yet again the case here. Brimming with the aforementioned exuberance at the prospect of heckling Porky, the cat’s entrance is largely rooted in intended innocence. It’s made clear that he wasn’t expecting to barrel Porky over and violently slam him into the wall—vacant, nonplussed head turns as he struggles to locate his one-man audience assert as such. Silence in the music score remains continuous, now with the intent to milk and build suspense regarding Porky’s whereabouts and how he’ll take this physical assault.

That the cat cautiously recoils upon the reveal of his damage speaks to his very little integrity; it’s a confirmation that he’s not out to hurt anybody, but just have fun. He isn’t intending to make Porky’s life completely miserable (even if that winds up being the case)—the one time he actually does end up jeopardizing him, even if it’s something as menial as a pair of black eyes, he seems genuinely taken aback.

…even if he’s quick to use this opportunity to lambast Porky even further, his ending lyric of “Where’d’ja get those eeeeeeeyes?” now elevated through the cruel irony reflected in front of him. The convenience of the scenario is what motivates the cat’s glee moreso than him reveling in Porky’s pain (which is minimal; the looks of the black eyes are the worst part, which keeps things lighthearted and palatable.)

Rather than rushing back into his house and invading Porky’s privacy further, the cat invests in the interest of being an omnipresent, enigmatic, transcendent pest. Eluding his pursuer reaps a higher entertainment value, reveling in the extra effort it takes Porky to discern where his feline headache resides now.

Right from whence he came. Cal Dalton assumes animation duties from where Gil Turner left off, offering broader context to the cat’s wailing performance of “Make Love With a Guitar”—his most contemporary selection, released in 1940 and even performed by Dennis Day on The Jack Benny Program.

As is usually the case, a method lingers behind Freleng’s directorial madness. Usage of that song in particularly doesn’t seem to be based entirely out of spontaneity; over the course of the past few songs, they grow and grow in their status as modern and contemporary. This being the most contemporary of all is fitting, given that it’s the last song the cat has prepared before he receives a final metaphorical hook.

A hook in the form of a gunshot.

Porky did it. Against all odds, against all obstacles—whether imposed by the cat or victim of his on sleepy circumstances—he finally, indisputably won, with the ring of the gunshot and the sharp, piercing yowl putting curtains on the cat’s performance leaving no room for rebuttal.

Like everything else in this cartoon, the resolution is beautifully delivered and is owed to a very conscientious process of preparation. Accentuating the permanence of Porky’s actions, animated smoke momentarily lingers in the air—a decoration that isn’t always utilized in the many examples of characters firing guns in these cartoons. It indicates an exchange of processes. Gunpowder has been fired, a bullet has been ejected, the smoke from the gunpowder hangs in the air as a manifestation of Porky’s consequences. This isn’t a fake-out. This isn’t a death scene à la Bugs Bunny where he’s faking his injuries or that Porky has missed. This is the real deal.

Which is why the scene is as effective as it is. Porky murdering the cat is almost a concession of sorts: an acknowledgement that his threats were not empty, were not decorative, were not for the convenience of the story. He really was out to kill the cat. It’s not that the audience isn’t meant to believe him—especially given that the cat takes the threat of the gun seriously too. Rather, there’s a sort of dubiousness, a “will he, won’t he” encouraged by Freleng. While we take sympathy on Porky throughout the cartoon, Freleng has intended for us to inadvertently adopt the cat’s line of thinking. To fall into that same gentle conceit that tells us Porky is unlikely to act on his impulses. He’s too tired, he’s too distracted, he’s just in a bad mood, the cat is too slippery.

No matter how subconsciously, we’ve underestimated him. The directing deliberately guides us to believe as such. Perhaps the harshness of the sting is exacerbated knowing that, well, duh, of course he killed the cat—the past six minutes have been leading up to this moment! Yet, there’s a certain gravity to be had when seeing it actualized. Freleng’s ability to be elusive with his directing, even at the short’s twilight moments, is yet again another one of his laundry lists of strengths. He keeps the audience guessing without indicating that we should know that we need to be guessing.

Vestiges of such dubiousness even sneak into the presentation of the cat. Having witnessed dozens of cartoons where characters perform the same dying skit with crocodile tears (both before and after this short), viewers are almost inclined to question the results. That he’s going along with Porky’s initiation could be flagged as peculiar if he was faking, given that he has little motivation to play along; that in itself speaks to the validity of his injury and Porky’s aim. However, a lack of blood and the melodrama of his weak, choking rendition of “Aloha Oe” suspend the audience in a state of apprehension. Freleng and the cat have teased us so much throughout the cartoon that even in his dying moments, it’s difficult to discern his sincerity. Maybe.

There really are no tricks: he’s done for. Dalton’s rendering of the cat teeters on the mangy side before his death, so his casting as the chosen animator here really gives a new depth to the cat’s histrionics. His raggedy fur—particularly in the muzzle—are a convincing fit for his coughing, choking, sputtering, and other palpitations. Even in the cat’s final moments, there’s a hint of playful disingenuousness as he haunts Porky with one last song. Dalton’s raggedy interpretation of the cat reminds the audience of the circumstances and gravity—moreso than would be the case if the cat kept his sleek appearance.

So, the short wraps itself in a bookend. It all starts and all ends on a fence: the same moonlit backdrop, once the proud stage for the cat’s performance, brimming with potential for opportunity, now lingers in the air with the cat’s swan song. Viewers are offered a direct means of comparison. How the cat looked at the beginning of the short, and how he looks at the bitter end. Humorously dark as the circumstances are, there’s a rewarding sensation of completion through such a bookend. The audience feels as though they have genuinely braved the elements as much as the characters. They’re able to compare the two footnotes and parse out all of the events that happened between them; the story has a definitive beginning, middle, and end, with such coherency favoring Freleng’s attuned directing.

“Farewell… farewe-ell…. to… thee…”

A lightheartedness is shared between the sound effects and the music. Mischief of the slide effect marking the cat’s fall is supported through Stalling’s descending flute motif: while these choices seek to lighten the mood, entertaining the hammy theatrics of the cat’s death, they reflect a rather bitter irony just the same. How many deaths in these cartoons—real, actual deaths—have been tolled through the insulting juvenility of a slide whistle?

Jocular sound effects or no, it certainly doesn’t detract from Mel Blanc delivering one of his most powerful monologues as Porky yet. It isn’t so much the dialogue itself as it is the conviction, the sincerity, the dripping remorse and even self directed horror carried in his words. In spite of his explicit desire to rub out the cat throughout the entirety of the cartoon, Porky regards the consequences of his actions—and actions themselves—with an earnest horror.

“I’ve keh-eh-keh-eh-killed him!”

For such a crushing realization, his voice remains hushed, stolid, approached with the same gentility and nuance so subject to praise before. Discarding of his gun isn’t done consciously: it drops out of his hands, as if the mere touch of his murder weapon is too overwhelming of a reminder. He doesn’t look out at the window, or at the gun, or to the ground—a thin veil of vacancy wedges its way between his gaze and the audience, as though he’s not all there, too preoccupied in his own terrified remorse. However, conducting such a gaze in our general direction induces a pathos, a connection with the audience that renders his horrified realizations all the more personal.

“Oh… I eh-deh-de-didn’t… wanna do it…” The strain, the hesitancy, the sheer distress in Blanc’s vocals are masterfully delivered. Sentencing the cat to death is pretty brutal, but, analyzed through the barest essentials, is somewhat amusing. All of this over an over actualized metaphor of cats “singing” outside the window and keeping people awake? The absurdity of this scenario is something Freleng keeps in mind throughout the short, but is exceedingly careful in ensuring it doesn’t undermine or delegitimize any of the story points or directing. In other words, Porky isn’t made fun of for his remorse, just as he isn’t lambasted for his vulnerability and quickness to fall asleep. By playing his grief to the utmost sincerity, Freleng achieves in his mission of drawing coy attention to the absurdity of the scenario than if he were to explicitly note as such. Conviction is confidence.

Blanc’s performance is nothing but convicted. The pain and terror in Porky’s deliveries are all too genuine. A choked, restrained pause lingers before the “wanna” in “I didn’t wanna do it”, indicating how carefully Porky is parsing his words and the gravity of the situation. He is really thinking hard about this—too hard.

“Buh-be-eh-buh-be-eh-but I just had to,” is more breathless and despairing as he begins to bargain with himself. Indeed, it sounds as though he’s struggling to alleviate the mental weight off of his shoulders. “He was driving me ceh-cee-eh-cr--neh-nee-nuh-nuh-eh-nuh-neh-neh—crazy…”

Those last handfuls of sorrowful stutters are met with an audience. Not the audience watching the cartoon, but the audience within the cartoon: a sudden menagerie of harmonies materializes off-screen to Porky’s visible surprise. Timing of the realization is, yet again, handled carefully and consciously. A certain restraint is exercised in ensuring Porky doesn’t react as soon as the first hint of a voice introduces itself—that would be all too convenient, which would lessen the believability so painstakingly cultivated through the past seven minutes. These brief delays are a necessity to any reaction from a character in any circumstance, but is nevertheless especially imperative here. Porky is so suffocated by his own guilt that it takes him a few seconds to even realize what’s going on.

To a lesser extent, the same could be true for the audience. That directorial dubiousness hinted at in the cat’s death sequence—asinine as it may seem to theorize—is realized here. With this sudden resurgence in song, the audience is led to believe that, indeed, the cat has been faking this whole time. His facetious sing choice of “Aloha Oe” was too perfect, the lack of visible blood was too perfect, the melodrama in his staggering steps was too perfect. This, too, was all another elaborate ruse to get back at Porky, playing with his emotions to the highest extent. Freleng left that little room for interpretation to go either way: Porky mourning his own actions and the cat’s death has a clear motivation behind it, just as the suspicion regarding his still being alive has a motivation behind it. Nothing is exactly black and white.

Through the courtesy of a relatively bloated run cycle to the window, we are finally greeted with an irrefutable dose of objectivity. Porky did kill the cat. He does have blood on his hands. The cat wasn’t faking. All of the guilt and fear expressed by Porky is still gratified in a sense: Freleng is careful not to completely undermine such an emotionally vulnerable beat.

However, this outcome is almost worst than if the cat were still alive. Instead of one voice taunting him, it’s 9 of them, all collaborating to bring Gaetano Donizetti’s “Sextet” from his opera Lucia di Lammermoor to life.