Disclaimer: Being the 7th entry of the infamous Censored 11, this review contains racist content and imagery for historical and informational context. I encourage you to speak out should I accidentally say something that is harmful, perpetuating or ignorant--it is never my intent and I seek to take accountability, should that occur. Thank you.

Release Date: September 13th, 1941

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Tex Avery

Story: Dave Monahan

Animation: Virgil Ross

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Bugs), Darrell Payne (Hunter)

All good—or, perhaps more appropriately, important—things must come to an end. All This and Rabbit Stew marks Tex Avery’s final outing with his prized rabbit, whose notoriety and legacy is so largely dependent on the factors and attributes concocted by Avery’s imagining of him.

Avery has never been known to cling to one certain character for very long (at least, as far as his tenure at Warner’s goes.) Prototypal Elmer Fudd lasted the longest out of any of his creations, and even he was going through constant revisions in demeanor, voice, and design. Daffy barely lasted three shorts under his ownership before essentially getting adopted by Bob Clampett; Bugs comes in right ahead of him at four. For a man who is directly responsible for birthing some of animation’s most celebrated icons, one would never guess it from his comparatively humble treatment with his shorts.

Such is the anarchy of Tex Avery. As his career grew on, he was able to articulate and embrace his directorial voice. Find what worked, what doesn’t, see what’s worth salvaging and what deserves to be discarded. Getting into the psychology and emotionality of the characters was never high on his list of priorities, especially in late 1941. Gags always came first. How best to make the audience laugh. Usually, his characters served only as a vessel for that laugh. Endearing the audience through charming, engaging theatrical players no longer fit his needs.

This is likewise the case for this particular cartoon. Bugs Bunny is still recognizably Bugs Bunny—he isn’t nearly as proudly one dimensional as many of his characters at MGM would be, but it’s clear that Avery was beginning to regard him as a plaything. He provides a means to an end for a gag or a laugh. A handful of instances even go out of their way to assert the superficiality of the character through abstract visuals that succeed through their detachment. More will be covered on that later; for now, the approach Avery takes in this cartoon can unequivocally be traced to his work at MGM. Work that prided itself in its subversive, surrealist transparency where characters are barely even flesh and bones. They’re whatever best serves Avery in the moment.

Of course, the legacy of this short (if one would call it that) isn’t necessarily this abstract approach taken with Bugs, nor is it relevant to being Avery’s last outing with the character. Rather, it’s the first short in 3 years to be sentenced to the infamous Censored 11 list, ranking in at #7. While the Censored 11 is ultimately a decorative footnote rather than a strict guidance, being that is was concocted solely due to TV broadcasting rights (and the fact that five times as many cartoons exist out there that are equal, if not often stronger, in severity), it being included on that list does paint a picture of what the short entails.

Voice artist Darrell Payne plays the role of the hunter, modeled after the performance of Lincoln Perry’s Stepin Fetchit character. Unfortunately, woefully minimal understanding exists as to who Payne was or what he did. His vocal talents can also be heard as the wimpy Mr. Meek in The Wise Quacking Duck; other than that, that’s about all we know.

He serves the purpose of Avery’s vision well. That is, a vision to push the envelop and be as crass and extreme as possible. This is a philosophy that applies to Avery as a filmmaker in general—not just this cartoon—but his tendency to shock and surprise does no favors in rendering this as a pleasant, incontestable, humane romp. Avery does lean quite liberally into channeling frequent stereotypes and caricatures. Great news for all of the clueless parents out there buying a public domain VHS tape out of the bargain bin, in which this short (being in the public domain) was ever so widely included—thus, little Billy is free to digest these stereotypes at face value to his little heart’s content.

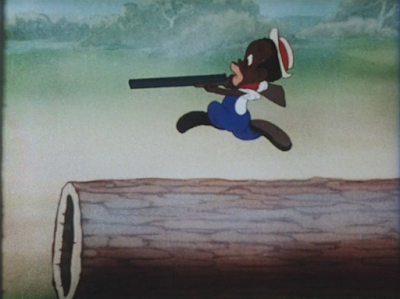

If there is a benefit to be had, it’s that the short doesn’t try to be duplicitous or coy with its presentation. Everything we need to know about this cartoon is established right at the beginning:

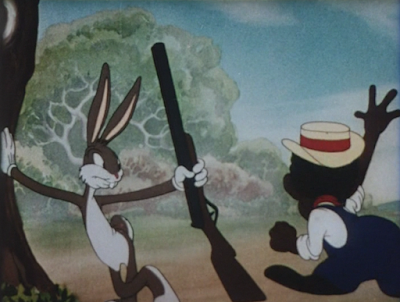

What you see is certainly what you get. Payne’s voice for the hunter is whiny and extravagant, serving Avery’s intentions of comedy. Comedy that is, of course, reliant on a barrage of stereotypes; his posture, shuffling walk, and lackadaisical gun dragging are all highly reminiscent of attributes to the Stepin Fetchit character.

Already, the short is flawed. Racism or no, even if the hunter happened to be white, opening to such a pitiful image communicates an imbalance. It’s exceedingly clear that Bugs will have no problems whatsoever messing with this hunter or ruining his life. Outside of the threat of a gun, there isn’t much that paints the hunter as a worthy adversary. Such is the “Elmer Fudd” dilemma, of sorts—at the very least, Elmer has the benefit of his entitlement that can be rewarding to watch unravel. As soon as the fade from black rises to completion, our hunter here already has a target on his back. There’s a fragility in more ways in one that proves unpleasant to see exploited.

Avery almost seems to be poking fun at the very formula he established—the ease in which the hunter stumbles upon the rabbit tracks is almost too convenient. He begins to exclaim upon finding the tracks before the camera has finished panning and allowing the audience to see what he’s looking at. No sense of anticipation or tension or exposition whatsoever; it’s handed to both the audience and the hunter on a silver platter. Sheer convenience is the gag.

That he barely even turns his head to acknowledge the audience when pointing out the rabbit tracks is a nice touch. It doesn’t so much seem to be an encapsulation of stereotyped laziness as it is following the promptness of the set-up. Both Avery and the viewer know exactly where this is headed. Thus, no point in pretending otherwise.

Conspicuousness of Bugs’ hole is, likewise, a joke all its own. Three out of four of Avery’s Bugs cartoons open with the rabbit making an entrance out of his hole. A Wild Hare and The Heckling Hare at least make attempts to meld the hole into the scenery; the viewer laughs at Willoughby’s delay as he sticks his head right in the hole and keeps trudging forward, but can at least see how he would do so. The hole is rendered to be a part of the background. Here, however, right in the middle of the field, nothing surrounding it, no shading or rendering to give the hole an illusion of anything but an opaque blob of paint, his “hideout” is just as conveniently located as everything else. All of the elements for the formula are there, stripped to their barest essentials. It almost reads as a commentary on Avery’s feelings of immobility at the studio, expressing a desire of wanting to do more and the free reign to do it.

Bugs’ entrance in this short has perhaps morphed into one of the most recognizable pieces of exposition. Isolated, slightly tinny crunching and chomping indicate that the hole bears an occupant. The butt of a consumed carrot is thusly discarded—there’s an endearing conceit in such a maneuver. A fun visual gag, of course, but it also sends the message that the world is Bugs’ trash can. Casual and innocent as his littering may be, a certain pompousness is inherent to it, too.

It’s a gag that even the most casual viewers of Warner Bros cartoons have come to recognize. So, to think that there was a time where nobody had ever seen anything like this comes as a surprise. History in the making—this is the very first occurrence of a beloved gag that would last for years to come.

Avery likewise includes a clever topper that is unique to this very routine. After another carrot has been discarded, more chewing commences… only for an aggressive frenzy of spitting to take precedence.

An uneaten carrot prominently lacking its fronds is thusly discarded contemptuously. A very clever gag that relies on a purposeful hint of monotony to lull the viewer into a false sense of security; obeying the ever fabled rule of threes likewise induces a gratifying rhythm in the structure. So much is communicated through only audio. The resulting visuals serve more as a means to an end than an entire explanation.

Those anxious about the prospect of Bugs leaving a fresh, uneaten carrot out in the wild can likewise put their concerns to rest. A suspension of any background music accentuates this shift, testing the audience to see if they’ll really believe he has the awareness to catch his folly. Commencing of chewing sounds shortly thereafter indicates all is as it should be.

Except for when it isn’t. Our hunter enters the frame to a degree of passiveness we haven’t really seen yet—he doesn’t immediately thrust his gun down the hole or even make any indication of reaching for the gun. Instead, a hiccup (the censor approved substitute for a burp) from within the rabbit hole provides a brief distraction.

Likewise, a startled expression and hand to the mouth serves as a reply to his realization that he’s blown his cover. Ditto for the pitiful blinks at the camera, which gives him a sense of sympathy on behalf of the audience (where his design and minstrelsy does not.) Again, inflammatory stereotypes aside, it’s evident from his mannerisms alone that he’s already on the lower rung of the rabbit. There isn’t an air of conceit in his “gesundheit”-ing or even hunting, as there can be in shorts with Elmer. Elmer is similarly susceptible to exploit, but this vision he’s concocted for himself as a grand, threatening hunter is enough to establish why someone like Bugs would want to play with that.

The hunter may not be approached with a sincerity on behalf of Avery, but his mannerisms do seem more openly vulnerable. As such, seeing Bugs mess with him just reads as unpleasant. Baggage of racism certainly does no favors in rendering the affair any more pleasurable.

Nevertheless, the hunter now utilizes this opportunity to pull his gun on the rabbit. Knowing what we’ve seen thus far, his threats feel decorative rather than wholly motivated. Still, that doesn’t detract from amusingly brutal (and timely) lines such as “Put up them hands or else I’ll Blitzkrieg ya!”

Viewers will note the suddenness in which Bugs appears to surrender. Not once has he even entertained the idea of leaving his hole—the promptness in which he fashions a white flag, as though he had it on standby, is absolutely intended to raise suspicion.

Future MGM-isms manifest through Bugs following his pursuer’s orders. Having his rabbit hole slide across the ground and up along the tree is much more an abstraction than a motivated piece of insight into Bugs’ character. As was mentioned in the introduction, Avery’s characters suited him best as vessels for gags and surrealism. A Wild Hare and The Heckling Hare both feature delayed exits for the character to draw out a sense of anticipation, but it is still relatively telling that he’s remained so obscured here for so long. Particularly due to how much information with what he’s been doing (eating, spitting, hiccup-burping, surrendering, even just listening) has been touted. Bugs, at this point in the cartoon, is more of an idea rather than an actual being. If he were to exit his hole prematurely, then Avery couldn’t get away with surrealist visuals like these.

Avery likewise wouldn’t have been able to pull of the introduction of all introductions. Bugs’ formal entry into the short is one of its most inspired moments—fleeting and seemingly inconsequential as it may be next to everything else. After the hunter jabs his rifle into the hole in the tree, the camera jolts to a jump cut. Now, the rabbit hole is a fully rendered knothole in the tree, as though it had been there all along. Such a sudden jump reads as jarring and perhaps arbitrary, but serves as a refreshing kickstart to the burst of energy (and gunshot powder) that soon ensues. The camera pulls back to make room for the fiery explosion that envelope the entire screen…

…for a fade in from black to reveal a familiarly smarmy rabbit perched atop the rifle, carrot in hand.

The tree itself has been completely decimated, supporting Bugs’ abstraction. There is no possible way that he ever could have survived such a blast—especially if the sturdy old tree is wiped out from existence. Such is exactly the point. No longer is Bugs a woodland critter with a need for a slight attitude adjustment. He doesn’t have the same minor vulnerabilities that were once touted in A Wild Hare, or even Tortoise Beats Hare. Again, Avery’s Bugs isn’t so much a character anymore as he is an idea, a concept, a thing. This supernaturality renders him all the more enigmatic and intriguing, if not a little (or a lot) unfair to his opponents.

Open mouthed chewing followed by a familiar recitation of that fated three word catchphrase of inquiry ensues.

Now, the hunter indulges in his own routine familiar to many of Bugs’ adversaries of both past and present: gloating about how he’s nabbed a rabbit, only to realize said rabbit is staring him right in the eye.

Historian Frank Young in his own excellent write-up of this short notices an intriguing commentary in Bugs’ next act of heckling. Rather than planting a kiss on the hunter’s lips (which Bugs has done in every Avery short to date barring Tortoise Beats Hare, where Cecil initiates the favor instead), he instead pulls the hunter’s cap over his head. It does indeed seem likely that having Bugs kiss the hunter would have been regarded as taboo—hurtful imagery and a barrage of stereotyping, of course, is nevertheless welcomed with open arms. Regardless, such is where this short stands in its 1941 release date.

Bugs’ exit is another abstraction of sorts, but initiated with an almost antithetical sense of leisure. His swan dive off of the hunter’s gun is amusingly graceful, especially within the face of danger, and the swimming through dirt (with wood sawing sound effects creatively installed) is certainly a unique, inventive visual. However, both the music and action of him swimming through the dirt suggests an urgency of sorts that does not feel earned at this point in the cartoon. It’s perhaps too grand of a visual for what it serves as a response to. In spite of the threat of the gun, Bugs still remains with the upper hand. To operate at such lengths after mere stagnant banter seems arbitrary.

Bugs, however, does. Suddenness of his appearance (ruminating in an age old favorite pose, eventually a staple of stock imagery) capitalizes on earlier observations of his nonchalant, impenetrable omnipresence, but perhaps does suffer from being a bit too trigger happy. It’s an issue of stage direction—the camera spends a relatively generous amount of time watching as Bugs exits screen right, only to be waiting patiently at screen left barely moments after. His impossibility is an intended idea of the short, but is executed in this moment with such a breathlessness that the audience is inclined to feel confused. Even if only on a subconscious level.

Avery injects some Lennie-isms into the hunter for old times’ sake, spewing a plethora of “Which way did he go?”s amidst excitable hops and gallops. Bugs mimicking these hops to get on that same plane of excitement, both leading him on and mocking him is an admittedly inspired detail. Instead of reading as an unflappable bystander, this sense of participation (disingenuous as it may entirely be) keeps him mischievous and engaging, sustaining his wily spirit.

“Wily” is, likewise, a term suited for the run cycle of the hunter. Outside of the baggage carried by the design itself, the loose limbed, floppy footed running carries a zealous, manic energy that serves as another fore-bearer to the animation dominating Avery’s MGM cartoons. Having the hunter reach out and grab his hat to ground it back onto his head inserts additional visual interest to keep the animation varied, energetic, and organic. Moreover, Stalling’s boogie music score gives the running a motivation and depth.

Suddenness in which he halts comes as a surprise not due to the stopping, but the execution. Instead of engaging in an age-old favorite of skidding on his heels, tire squealing sound effects trumping an alarmed music sting, he instead appears to stop by his own volition. One moment he’s running. The next he isn’t, but his stopping is cushioned with just a few frames to give it a sense of purpose instead of complete spontaneity.

Sucker gag, which has been crawling to a standard punchline since its conception in Gold Rush Daze, serves as a natural payoff. It’s difficult to imagine the lollipop being black if it were any other character. As if that comes as a surprise.

Bugs taunts his foe through the sanctity of a rabbit hole—has the same one from before somehow melded back into the ground? Has he since spent the time digging another hole? Both are irrelevant, as they do not serve Avery’s current purpose. All he needs is for Bugs to be in a hole. The how or the why that gets achieved is no longer a priority.

Its existence serves as an enabler of another rather random gag—the hunter grabs a plunger to unearth his dinner. Polite (if not bizarre, thanks to the convenience of the toilet plunger) now, such inclusion of bathroom related imagery likely raised some hackles in the Hays Office.

Another hat smothering in lieu of a kiss. Bugs posing as metaphorical excrement fished out of a metaphorical toilet is okay, though.

Avery channels the likes of The Heckling Hare with Bugs next means of defense: tickling him. The gag works more comfortably in Heckling, seeing as he was genuinely playing with (and exploiting) Willoughby’s impulses. Here, it’s unclear what the maneuver is set to accomplish.

It nevertheless is best viewed as a tangent, as it’s barely on screen long enough to give the audience time to raise questions. Bugs smacking the hunter with the end of the plunger—another somewhat spontaneous action that blends into a cacophony of ideas rather than fully realizes beats—takes precedence.

Ditto for a stilted run cycle on behalf of his new accoutrement. The cycle feels as though it could stand to be faster, more spontaneous, more natural; the repeated banging of the handle against the ground is orchestrated in such a rhythm that it almost seems like Bugs is doing it on purpose.

That, too, is nevertheless discarded in favor of more spitfire gags. Avery enacts and indulged in his own special jurisprudence: a rabbit hole will always be at Bugs’ convenience, no matter the location or the probability.

As repetitive as Bugs’ repeated sanctuary has been, it does offer a relatively inspired subversion. Inspired on behalf of the prompt timing, in which there is hardly a beat missed, and inspired on account of evoking a gag from Bugs’ dawning moments. Pulling a skunk out of the rabbit hole, thusly affixes to the plunger, is thrice as quick as the skunk reveal in A Wild Hare. Both moments are armed with their respective backgrounds—Hare’s example isn’t inferior just because it’s slower—but the promptness of the reveal is genuine in its surprise and energy. There isn’t a best long enough for the viewer to even speculate that something other than Bugs will be unearthed from the hole.

That same hyperactivity persists in the hunter’s discarding of the mustelid. From his reaction to burying it in the hole, the energy persisting in the scene is once again comparable to the sort of zeal and breathlessness so native to Avery’s shorts at MGM. Comparing the routine to A Wild Hare’s—whose comedy capitalized upon a creeping, slow burning realization—is truly enlightening.

This, too, is rewarded by more taunting from Bugs. Bugs’ role in the cartoon is almost like a reverse Droopy of sorts; in Avery’s world, Droopy serves as an omnipresent pest who is able to turn up at any and all corners, psychologically torturing his victims (ie. the wolf). Just as the wolf believes he’s finally safe and alone to himself, his world is shattered through the reveal of a lethargic, puny little dog.

Bugs does the opposite. Maintaining those omnipresent, taunting qualities, he lures his victim towards him rather than explicitly appearing at his side. This, of course, manifests through diving into rabbit hole after rabbit hole, or performing a coy (yet incredibly charming) vaudevillian exit into a nearby cave. Stalling’s soft-shoe adjacent musical accompaniment really ties a seemingly meaningless gesture together. It’s mischievous, it’s energetic, and a sheer expression of playful lackadaisy: a middle finger to the hunter trying so hard and exerting himself so strenuously to nab his prey.

Flop footed run cycle is directly repeated as he lunges into the cave. There could likely stand a more intriguing means of entry that isn’t reusing animation, but of all the animation cycles to reuse, this one is certainly a good candidate. It moreover creates the illusion of substance through serving as an informal bookend.

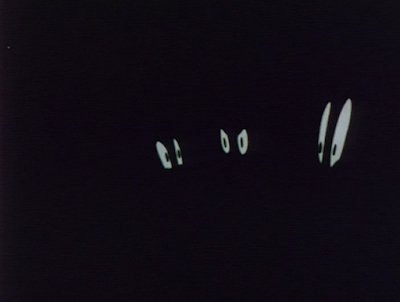

With caves come glowing eyes—a routine Avery has indulged in even as early as 1936’s The Blow Out. Already, it’s exceedingly apparent that the second pair of eyes in the dark are not those native to Bugs. That would be too easy. Instead, Avery uses this opportunity to tease what the mystery guest is rather than if there’s a mystery guest.

Bugs’ eyes do eventually come to fruition. Just now where the hunter expected them to be. Rather than having the pair of eyes bob in from screen left, incurring the illusion of Bugs strutting into frame, they instead pop open with an exaggerated overshoot that wonderfully captures his flighty spontaneity. It truly seems as though he manifests out of thin air.

Audiences are likewise able to piece together that said eyes belong to Bugs through their accompanying nasal drawl. It’s that same three word inquiry that requires no introduction—only with “cookin’” substituting “up”.

Dry brush on the hunter’s eyes as he looks back and forth reads somewhat arbitrarily, but that could be likened more to the speed in which his eyes move (or lack thereof.) If the drawings were spaced further apart and timed to be quicker, then the dry brush would read as a more helpful conveyance of urgency. Instead, its usage appears accidentally decorative rather than bearing a true function.

As indicated through the reveal, our hunter has a right to be apprehensive. Avery would reuse this exact same setup in Half Pint Pygmy seven years after the fact; as one may correctly surmise, the routine in that short is three times as curt as it is here. Pretty telling to Avery’s comedic timing, since the execution here is relatively prompt in itself.

That same streaking fireball exit would likewise be refused. Here, our escapees have the benefit of a rabbit hole(!) to seek refuge in.

Make that #3. Though somewhat lost beneath the audible exhales from all parties, Stalling cleverly injects the NBC three note radio chimes to account for each entry of the character. Pitching the voice of the bear down an octave gives him a playful sense of authority, accounting for his huge size and how that juxtaposes against the comparative diminutiveness of Bugs and the hunter. This usage of the bear, as Frank Young notes in his write-up, certainly seems to confirm Avery’s involvement in Wabbit Twouble, as both bears are executed with similar sensibilities—be it drawing or acting.

Three-way surprise ensues. For perhaps the only moment in this cartoon, Bugs is on equal footing with his “adversary”. He may be able to appear at will and engage in genuinely impossible stunts, but he isn’t completely immune from the vice of his own conceit. Avery doesn’t seek to humble the character as he has in all of his previous shorts, even if those moments are fleeting. As such, this is the only true sense of vulnerability that Bugs possesses in the cartoon. Avery is no longer interested in exploring the rise and fall of the rabbit’s ego, what makes him tick and what doesn’t. He’s only a plaything, a means to an end, a purveyor of gags and comedic hijinks. In this case, vulnerability on his behalf works most favorably for the gag here.

This point is run home just a little bit longer, with Avery making the most of it while it’s on his mind. A shot of both Bugs and the hunter popping their heads out of opposite ends of the tree deliberately frames them as an exact parallel. Bugs isn’t besting the hunter, and the hunter… he’s never gotten the opportunity to best Bugs, but he certainly isn’t attempting to best him here, either. They unite in their shared apprehension of the bear.

So much so that they even engage in the same winded walk. Practically on top of each other, no less; if they were any closer together, they’d serve as a hybrid fusion. Avery explicitly turns this development of the two being on the same page into a gag in itself, a realization of a metaphorical idea.

Realization occurs in real time for both characters, too. Such is one of the short’s calmer, more down to earth moments that takes its time in engaging with more subtle acting. For example, the appearance of the hunter’s gun in the foreground is approached so casually that even Bugs seems disarmed. It’s very rare in these shorts for anyone to nonchalantly stumble upon the unoccupied artillery of their enemy, or even a discarded prop of any kind. It is almost always in someone’s hand, whether it be the agitator (which Bugs suits that role more here, admittedly) or the heckler. It’s a breach of cartoon convention, but a very subtle one at that. Such justifies Bugs’ rightful surprise.

Any and all vulnerabilities are fully out of the way—ironic, given that the hunter directly fires a spray of buckshot at the rabbit. However, the faithful act of hole diving proves protective once again.

Confusing, too. Purpose of the bullets is best served not as a murder device, but a purveyor of visual pantomime. A hand pulling back on a brake calls some of Avery’s earliest shorts so mind—particularly Milk and Money, where a horsefly engages in a similar gear shifting routine in midair.

Granted, braking is just as much a means to an end; hardly a beat is skipped before the buckshot amalgamate and transform into the visual of an arrow. Thus, its repeated pursuing of Bugs (delivered through a minefield of rabbit holes, almost seeming to poke fun at both Bugs and Avery’s reliance on the hole as a plot device) reads comparatively playfully. It’s easier to delegitimize and laugh at the danger faced by Bugs when he’s chases by a speeding arrow rather than a series of buckshot. Art Davis would utilize a similar routine in his own Riff Raffy Daffy.

Our seemingly interminable hole routine does prove to have a punchline. Does Bugs approach the putting green? Does the putting green approach Bugs? Who’s to say—the only thing that matters is that it’s a breach of convention that goes recognized by both the viewers and the participants in the cartoon. Bugs deems this hole an artifice before moving on to further affairs. Taking the time to remark on the hole being a fake—as opposed to using that time to run further out of the line of fire and save his hide—is rather telling. Menial of an act as it may be, it conveys a feeling of control. Something Bugs hasn’t been able to cling to wholeheartedly within the past minute or so.

While there is a requirement for the sequence to have a finite end, further viewing of the anthropomorphic bullets does grow a bit taxing. Perhaps that’s a side effect of the hole bit growing stale (even outside of the aforementioned sequence that deliberately attempts to tire the viewer), but audiences do find themselves longing for something more. Or, at the very least, something different.

Another skunk-as-a-punchline isn’t necessarily different, but it is varied. Bullets are put to rest for good as the skunk chases them off, shaking his fist and grumbling intelligibly; intelligibly in more ways than intended, seeing as the audio track implied for the character is not in the cartoon. His curses are silent, but communicated clearly nevertheless.

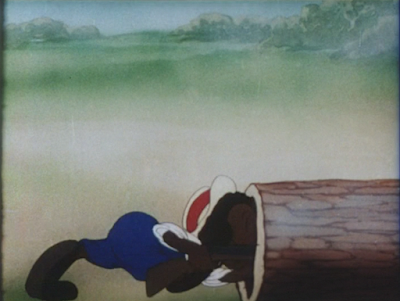

With that said and done, gears shift to a new tangent. Bugs messing with the hunter is once again made a priority—in this case, he beckons him over from the sanctity of a hollow log. Arranging the composition so that the hunter lurks in the distance sustains visual interest and keeps the environments immersive, but works to the benefit of Bugs’ taunts, too: such a distance between the two indicates that there is a gap that needs closing, that the hunter has to work to approach Bugs, which makes it all the more tantalizing.

If The Heckling Hare’s divisive monotony stems from repetitious falls off a cliff, then All This and Rabbit Stew’s purposefully devoted monotony originates from Bugs and the hunter running through the lot. It isn’t as outwardly obnoxious as Heckling’s outing, but does maintain that same playful narrative of poking the audience’s patience. Losing the music score and isolating the rapid, hollow sound of their footsteps running through the log is a particularly inspired touch that communicates so much through so little. So much so that the obtuseness of the sounds are a gag in itself.

This routine goes on for about three cycles, like any faithful follower of the comedic rule of threes. During the final cycle, the camera engages in a jump cut to Bugs rotating the log over the side of the cliff. The jump cut reads a bit jarringly—such is of course the intent, banking on the audience to lose themselves in the monotony and be as surprised as the hunter, but there nevertheless does seem to be a smoother way to approach the change.

…as does another sucker take. Here, the transformation is twice as quick as its initial introduction minutes ago. Avery trusts that the audience has gotten the gist by now and doesn’t need the the reprise to be spelled out.

This routine is thusly reprised once more as Bugs rotates the log again to keep torturing this poor soul. Yet another sucker gag is perhaps a bit too overzealous—at least in such a short amount of time since the last one. Nevertheless, it’s evident that neither Bugs nor Avery are willing to relent.

As the hunter seeks refuge once more, the camera pan of a decidedly rendered log indicates an immobility. Perhaps Bugs has finally had a change of heart—the hunter takes his time to feel up the solid ground and ensure that it is safe for his run cycles.

It’s not, of course. Such “generosity” was merely a red herring on Bugs’ behalf: just as the hunter finally believes himself to be safe, the rabbit rushes out from the sanctity of a rock and sends the log leering over the edge of the cliff once more.

A tight close-up on the hunter traversing the lack of ground indicates a breach in convention. All other routines have been viewed slightly from afar—that this one is so close in registry indicates a need for that to be changed. Thus, a new routine.

Routine being that this time, the hunter actually falls. Bob Clampett would reuse this same bit in his own The Big Snooze, with Elmer in place of the hunter. The entire routine is of course cruel in this particular context, but the slow burning realization and the hunter’s reactions are approached nicely. A solid antithesis to the rapid fire running and turning and lollipop transforming.

Laws of gravity are thusly enforced. Avery frames the staging so that we view Bugs’ reaction to the fall, rather than tracking the act of the descent itself; conveying the demise through context clues and leaving it up to the imagination of the audience is more brutal through there mere act of not knowing. Spelling everything out on screen ironically enforces a restriction of sorts—the fall can only be as brutal as it is depicted to be. Bad news if a particularly weak animator were to tackle it. Instead, watching Bugs flinch at the eventual collision communicates all we need to know.

“Too bad… too bad!” The tone behind Bugs’ words are incongruous with the sentiment of the words themselves. A flippant resignation of “Oh well!” is more accurate to his feelings on the matter.

One would be remiss not to note the similarities to The Heckling Hare. Through monotonous routines and cliff falling, yes, but even the eventual shrugging of the shoulders as Bugs walks away free. The comparisons are so apt that it almost seems entirely deliberate from Avery—perhaps knowing how much friction the ending of The Heckling Hare had caused with the management, there’s potential for him to hint at that debacle through such a loose reprise here. That, or he just thought it suited the needs of the short best. Either way, there is certainly an unavoidable comparison.

Such initiated an incredibly formative glimpse in Avery’s career. Bugs goes to pieces at the sight of the rifle: literally. It’s a split second take, but perhaps the very first and foremost, true, formal “Tex Avery take”.

On the surface level, it’s just a fun, playful visual and means of exaggeration. It’s loud. It’s interesting. It’s caricatured. However, it supports an argument that has been reinforced throughout this cartoon: Bugs isn’t a flesh and blood being so much as he is an idea, a caricature, a pawn for Avery to manipulate how he sees fit. It isn’t an intricate commentary on Bugs’ character and how he operates; it’s an extreme reaction, an extreme discard of cartoon convention that Bugs just happens to be the purveyor of.

Likewise, outside of the novelty of being the first tried and true Avery take, there’s the additional novelty of realizing that this take is extremely unique to the Bugs of this time. Such a candid (to a degree of borderline disingenuousness) reaction would never be found in association with the character 10 or even 5 years later. That reactivity was abandoned in the name of control and caution as the directors had finessed the chemistry of Bugs Bunny. These wild, exuberant proclamations weren’t best suited for what they decided the character was to accomplish. (Someone like Daffy, on the other hand, is a different story.) For those so used to the unflappable rabbit the world has become to know and love, this take here almost seems like a violation.

A small technical critique: the camera panning back and forth to encapsulate the take has potential to read in a more coherent manner, and almost comes as a distraction. Nevertheless, the novelty and brashness of the take certainly trumps any technical nitpicking.

Unfortunately, coming down from the high of the take is strong, as it leads to the short’s cruelest vice. Shaken at the sight of the murderous hunter, Bugs begs for him to relax, easing the rifle away from his chest. Unsteady as his voice may be, his intonation nevertheless hints at a backup plan. Another somewhat distracting jump cut to a close-up shot cements such an idea…

Gambling has long been a stereotype associated and attributed negatively with Black culture. Many have pointed to D.W. Griffith’s infamous Birth of a Nation as being a particular enabler of such a stereotype, demonstrating its Black characters as gambling, womanizing drunks (this, of course, being the same film that paints the Ku Klux Klan as the noble heroes.) It isn’t to say that such a stereotype is directly attributed to that very film, but it does play a part in furthering the association.

It’s nevertheless been persistent enough to frequent many golden age shorts featuring Black stereotypes, of which this is no exception. It necessarily isn’t the inclusion of dice in the short (which is still low), but moreso Bugs using it as a deliberate vice against the hunter. Playing on his impulses and knowing his inability to resist a game of shooting craps. It is purely manipulative and perpetuating—the sheer smugness on Bugs’ face as he knows he’s got the hunter cornered is nothing short of contemptuous. It’s a routine that is exceedingly targeted; there is no “well, we didn’t know”-ing about it. The deliberate antagonism of the tone certainly comes as no accident.

Craps shooting thereby commences. If there is a benefit to be had from such a rotten display, it’s that it is, at the very least, approached inventively. Bugs and the hunter take refuge behind a conveniently situated bush overlay: audio cues thereby inform the audience of all goings-on, as well as the sporadic shaking of each other’s hands. Both voice artists are animated in their deliveries, succinctly conveying an exciting and titillating game. Stalling’s swinging accompaniment of “What’s Your Story, Morning Glory” is a thing of beauty—a shame it has to be wasted on something so egregious.

It likewise isn’t the mere act of gambling that’s so targeted. A factor, of course, but the outcome plays a big part: the music comes to a halt, followed by a cautious “Eh… sorry, doc” on Bugs’ behalf. A sting of defeat…

…soon to meld into utter humiliation for the hunter, and disgust from Bugs. Touting his clothes and gun, Bugs reprises the hunter’s entrance at the top of the cartoon with dripping disingenuous that reads as sheer contempt. All of this following Bugs’ attempts to play on the hunter’s vices, manipulating him throughout this entire ordeal, just leaves a bad taste in one’s mouth. Even if the baggage of racism didn’t dangle over the cartoon’s head, the act still reads as particularly juvenile and just plain mean. It proves easier to make these claims in a post Bugs Bunny world, where we take the gift of foresight-turned-hindsight to granted all too often. Bugs was still too fresh of a character to tout a definitive list of do’s and don’ts. Nevertheless, his behavior here cements an all too purposeful awareness and intention to belittle and dehumanize.

“Well, call me Adam,” is the hunter’s take on the matter. If he can’t be left with his dignity, then at least a sense of humor proves to be a safety net.

One that is proudly and shockingly violated by Bugs, who interrupts cartoon convention to strip the hunter of everything he has. His leaf stealing isn’t a coy aside reeking of “ain’t I a stinker” and all its faux innocence. Here, he props it up as a trophy; a symbolism of his antagonization and belittlement. Thus, Avery’s rabbit takes his final bow.

Model sheets label the hunter as “Tex’s c—n”, so to expect a glowing portrayal of a Black person is a fool’s errand. Still, this cartoon proves that Avery’s desire to shock the audience and push social boundaries (to the point that even the short had to make accommodations—kissing the hunter is a no-no, the dice are curiously not mentioned by name) was successful, even for 1941’s standards.

Deeming the short a “mixed bag” almost seems too easy, too infantilizing of the harmful imagery and stereotypes and ideals perpetuated. But such is its fate: taking away the racist elements, the short does read as a somewhat standards Bugs vs. sap-of-the-week outing. An outing that has its share of technical issues that would remain the same regardless of the hunter’s skin color; occasional incoherence in shot flow, an overzealousness in ideas that seemed to work better on paper than in execution, repetition that extends beyond what was intended. There seems to be a growing embrace of indulgence on Avery’s behalf as the limitations of the studio seem to get the best of him—this isn’t a bad thing thing by any means, as it spawns such moments like the first ever Avery take.

However, the usual restraint he was able to maintain for so long seems to be slipping. Usual bits of directorial maintenance fall through the cracks as his vision tunnels. Making people laugh was always a priority throughout his entire career, but it does seem that, at this point in time, he wanted to make what would make him laugh. This is genuinely as noble a pursuit as any… but one that’s likewise landed him in hot water, if The Heckling Hare is anything to go by. His desire to innovate and indulge unintentionally seems to be leading to an accidental “ignorance”, of sorts, or an indifference to error.

Said errors are not make or break moments. Audiences do not stroll out of the theater gossiping about how peculiar it was that Bugs spent so much time “swimming” screen right, only to be waiting so patiently behind where he even started barely seconds after. Theatergoers aren’t moaning about how Bugs’ rabbit hole was a directorial crutch. Nobody had the sense to go “I don’t think Bugs Bunny should be so cruel—that doesn’t serve his character best” since his character was still so enigmatic at this point in time. This short has its fair amount of flaws, but remain relatively understandable in where they come from.

Which leads us back to the racism. While it’s true that this is essentially just another Bugs Bunny cartoon with the same Bugs Bunny formula, it’s a short that proves difficult for one to “well, but…” their way out of. Particularly since the ending makes such a blatant point to be as egregious as possible. Bugs preying on age old stereotypes with such violent smarminess, only to completely delight in ravaging the hunter of his dignity (following six minutes of psychologically torturing and straining the poor sap) is no accident. It is a deliberately mean-spirited jape that sure, whatever, can be dismissed as a product of its time, etc. etc. It cannot be dismissed under the defense of ignorance, however. Not that stereotypes and caricatures cast out of ignorance are innocent in other cartoons, but Avery’s blatant attempts to expose just how purposeful the entire charade is really leaves an incredibly sour taste.

It’s not a pleasant cartoon. Racism or no, it isn’t satisfying to watch Bugs torture a poor soul who he immediately has the upper hand on. Even Elmer Fudd, who is prone to similar issues but still has his white entitlement to cling to, was thought to be too soft against Bugs. Such is why we have Yosemite Sam in the world.

It nevertheless remains difficult to shout “foul” at this, since it’s so early on in Bugs’ career. All of these cartoons are a product of experimentation. Tex Avery couldn’t look 4 years into the future and think “Well, Bugs has a more suitable adversary here—maybe we should change how he treats our hunter in this case.” It’s thanks to shorts like these that Bugs was able to develop that “safety net” for himself. The only way to experiment and to grow is to do. Even a misfire is still an important step.

A final note, historians may or may not be intrigued to note that this hunter even makes an appearance in the Dell comic issues, dubbed—what else—as Sambo. One is inclined to ponder the reception of this cartoon; surely it received enough notoriety for the hunter to be adapted into print, no matter how menial said adaptation may be.

It’s not a proud moment in Bugs or Avery’s career, but such is the life of this journey. Perhaps some of the sting of the short is sourced from Bugs’ complicity; to watch one of pop culture’s greatest heroes antagonize and belittle and harass someone so vulnerable and utterly pathetic does little to make him endearing or proud. It’s easier to dismiss a “standard” Censored 11 or any other short made in prejudice if no important characters tied to it. (Does anyone really care about something like Tokio Jokio outside of its reputation as being an utterly repugnant cartoon?) Throwing one of the most beloved fictional icons of all time into the equation—and as a ruthless aggressor, no less—introduces a personal element that renders the final product all the more uncomfortable.

But, again, such is the life of this journey. Growing pains are entitled as such for a reason. Outside of the racism, the short has its flaws and remains relatively unremarkable. It conversely opened the way for some of Avery’s most important moments, soon to be realized at a studio other than Warner’s. If anything, this short puts his restlessness to paper; it’s clear he requires an outlet to be as bold and expressive and inventive as he wanted. That day would soon approach. Even if it didn’t happen to be today.

.gif)

.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment