Release Date: August 30th, 1941

Series: Looney Tunes

Director: Bob Clampett

Story: Warren Foster

Animation: John Carey

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Daffy, Porky, Crowd), Sara Berner (Mrs. Duck, Hen, Crowd), Bob Clampett (Sound effects, Crowd)

(You may view the cartoon yourself here!)

Sometimes the most difficult aspect of formulating these analyses isn’t the analyzing itself—but, rather, concocting an opening.

Part of it stems from an innate subjectivity. There are so many routes to take when introducing a cartoon; the objectivity that is cold hard facts. Such and such cartoon was released on this date, and started production on that date. Cast and crew includes so and so, whatshisname, this, that, and marks the first credit of such and such before heading off to so and so.

Or, there’s a more candid opening, offering personal musings that are reflective of biases and opinions. Biases and opinions I strive to make a point to note of; not to flag them, but embrace them. Learning the cold hard facts—the who, what, when, where, why of the short—is gratifying in its own right, but something that anyone could report on. An injection of a more personal point of view offers a uniqueness that gives these analyses a slightly deeper layer.

Then, there are the analyses that open with musings on how an analysis opens. Such as this one.

Why bother? Who cares? What importance could an introduction to this random black and white Looney Tune (almost) released in the last quarter of the year possibly hold? Why the belabored, monotonous ramblings? It’s not as though this short is as significant as A Wild Hare or You Ought to Be in Pictures, or any other “flagship” cartoon.

I write all of this to lead to a more candid point of view. One that I know is more tailored to my own experiences and is not an objective retelling of fact. Not that objectivity is a make or break determinant of quality, of course, but nevertheless.

In formulating my notes for this short, I’ve come to a realization: much of my personal perception of Warner Bros. cartoons can be divided into two factions. Those that predate The Henpecked Duck, and those that follow The Henpecked Duck.

That’s quite a lot of responsibility to shunt onto one cartoon. Such is partially why I’ve been taking the lengths to formulate such a long opening about subjectivity and candidness—I don’t believe the legacy of the studio “hinges” on this cartoon. If one were to view the studio as a before and after, there are many more qualified candidates for that criteria. The output of the studio before and after A Wild Hare. The output of the studio before and after Gold Diggers of ‘49. Porky’s Duck Hunt. I Haven’t Got a Hat.

Those that know me can attest that I am a Daffy Duck fanatic. He is indeed my favorite figment to ever stem out of anyone’s brain matter—at this point in our venture, we haven’t exactly gotten to a point where I’ve been able to expand on the how or the why in great detail (compared to, say, Porky, who I hold a very similar reverence to and many of the shorts we’ve encountered are indicative/evidence as to of why I hold that opinion.)

That changes with The Henpecked Duck. To me, this is Daffy’s crowning moment. The effects of his puberty that have been growing and growing and growing over the past few years, boosted especially with You Ought to Be in Pictures, are finally realized here. He looks, sounds, and acts recognizably like Daffy Duck. Not that he didn’t before, but this short allows him to compare comfortably with his filmography in the next handful of years. In fact, Bob Clampett’s next short with the character wouldn’t be until 1943’s The Wise Quacking Duck—I am of the opinion that the Daffy here is more comparable to the Daffy of Wise Quacking than he is of A Coy Decoy, released just a few months prior.

A debatable assessment to be sure. Daffy’s growth ushered in this cartoon, however, not as much. Obviously, he’s still an ever evolving work and progress, and many impulses and influences in his behavior here are still very reminiscent of the duck of the ‘30s. Nevertheless—many developments and refinements touted by this cartoon, using his prior appearances as a mold and either embracing or reupholstering those previously established traits, are ones that make the character so enchanting and compelling to me personally.

So, with that grandiose introduction out of the way: The Henpecked Duck itself is a comparatively humble cartoon. It isn’t often regarded as the beacon of change and development like Pictures is, and the premise of the short itself rides on a homeliness of sorts. Both to embrace and destroy it.

Perhaps Daffy finds himself pinned against his greatest opponent yet: the divorce court. We, the viewer, are subject to an intimate look inside the proceedings, whether it be viewing the fall-out, the verdict, or—most importantly—just what constitutes the trial of Duck vs. Duck to begin with.

The last handful of Clampett cartoons have all made a positive impact through the ingenuity of their title sequences alone. Meet John Doughboy literally opens with a bang. We, the Animals - Squeak! touts a triumphant melodrama of flashy visuals, with the title card ripping to reveal the credits. Henpecked is comparatively more modest as far as the actual title card goes, but upholds a synonymous dedication and level of care in its composition.

Rolling pins dominate the background to support the cartoon’s title; always the weapon of choice in the many cartoon stereotyping battle axe wives. Utilizing photographs as opposed to drawings allows a certain gravity to thrive more comfortably—thoughts of taking a rolling pin to the head (which is what the background serves to imply) are more severe and tangible through the realism of a photograph. Rendering the rolling pins in a drawing, even when maintaining the same implications, concocts a very slight disconnect; a safety net of sorts, hiding behind the extra layer of a manufactured drawing.

Likewise, the credits of the auteurs are rendered in a neat cursive script. Outside of the visual satisfaction encouraged by the balance and contrast in different fonts, the serif communicates two alternatives: signatures on a wedding document, if Carl Stalling’s sardonic, “laughing” accompaniment of “The Wedding March” is anything to go by, or signatures on a divorce paper—both holding equal relevance to the story and conflict at play.

Through these opening credits alone, the audience already has a fairly clear idea of what the cartoon entails. So, understanding that notion, it is the directorial duty of Bob Clampett to keep them engaged by throwing everything they’ve been conditioned to expect out the window. Somewhat.

Introductions to the actual short at hand almost seem to be reliant on the confusion of the viewers. For one thing, the audience is physically kept in the dark—the fade out and in that precedes hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of cartoons doesn’t follow through on its second half. Submerged in the darkness of the screen, the only context present is the scattered escalation of one single sentence uttered by dozens of voices: “I want a divorce!”

Divorce was still a taboo at the time of this short’s release. Living together in [not-so] repressed resentment was seen as much more tolerable socially than the egregious sin of ever wanting to split ways—doubly so without a “good reason”. Granted, the divorce rate would reach record highs in 1946; of the threat of war had many couples rushing to get married, often to a degree of compulsion that came to bite them back. Nevertheless, it would take until 1970 for the first state (California) to legalize no-fault divorce. Normalization of divorce was making crawling progress. Progress, but progress that is still comparatively recent within our lifetime.

So, to open a cartoon not only with dozens of voices shouting about a divorce, but to approach some of the exclamations with such a lighthearted or even happy tone (such as one Blanc-voiced dope happily guffawing his own “Huh huh, I wanna divorce,”) was relatively shocking for the societal standards of 1941. Knowing Clampett’s love of toeing the line and stretching boundaries, that was exactly the point.

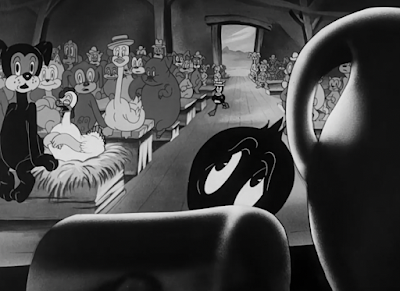

Darkness of the screen is attributed to the staging: whereas most cartoons open to an establishing shot that pushes in, often spurring a dissolve from one scene to the next, this one pushes out. Audiences are deliberately left in the dark as they strain to parse out why these disembodied voices sound so gleeful about the prospect of divorce. Thus, courtesy of an endearingly unsteady yet prompt truck-out, viewers find themselves greeted with the “court of inhuman relations”… otherwise known as the façade to what appears to be a henhouse.

Such is where that aforementioned homeliness stems from. Coziness of an idyllic barnyard is immediately juxtaposed against the heavy gravity of divorce and (in)human relations. Holding such important proceedings inside a henhouse almost feels like a bunch of kids playing pretend—like a lost Our Gang short with The Little Rascals. So, to hear such vitriolic discussions and topics within is both amusing and startling. A great example of how effective contrast is to comedy and tone.

Pushing back from the establishing shot acts as a way for the viewers themselves to step away and collect their thoughts. Indeed, the staging of the layout is reliant on that viewer participation and sense of immersion. The camera is angled low to the ground, looking up into the henhouse; such gives these decidedly dinky atmospheres a greater sense of authority and grandiosity, as well as further a hint of acceptance. That we are small enough to fit into this henhouse implies that we are a part of these inhuman relations. We aren’t an outsider looking down upon this separate judicial world. We are a part of that world. We are that world.

Voice expert Keith Scott pins Bob Clampett himself as contributing to the crowd of voices changing for a divorce. Indeed, the 5th “I want a divorce!” (and likely more) sounds very similar to his role as one of the hunters in Horton Hatches the Egg, in which Scott also identified as him. As mentioned in previous reviews, a wider voice cast enables a broader range of authenticity. Mel Blanc enlisting in his rotating tool belt of voices is always a blast to hear, but is almost always recognizably himself. Adding Sara Berner and Clampett into this mix (and perhaps even some others) allows the crowd to seem bigger, more full, and more imposing through a greater, more believable laundry list of voices to choose from. This is especially helpful for the needs of the introduction, which has all of the voices rising into an unintelligible crescendo of shouting, arguing, demanding, and other synonymous displays of discord.

Perhaps no voice is more cacophonous than that of Porky Pig’s. Simply excelling at his job as the keeper of the peace, circuitous demands of “Order in the ceh-ih-ceh-court! Order in the court! Order in the court!” drown the cacophony of screaming and yelling, which, in turn, is drowned out by the delightfully ear shattering smacks and bangs of his gavel as he slams it against the podium with startling ferocity.

Viewers will note that the camera initially fixates on the gavel rather than Porky. All attention is immediately thrust on the most aggressive, most violent gesture—smacks and bangs of the gavel register before Porky does and his role as judge. Such focus is especially curated through the playfully unconventional tear transition that precedes his (or, more accurately, the gavel’s) introduction.

Clampett’s sound design—or lack thereof—is the glue that cements the scene together. An imbalance of volume between the echoes of the slamming gavel and Porky’s protests almost sounds erroneous, but such places an inescapable highlight on the mere concept of the chaos and discord. Incomprehensibility is the goal; Clampett achieves it in a manner that still feels motivated and intelligible rather than wholly accidental.

Much of that is owed to the punchline, if one would dub it that. Furthering the sensation of the viewer “stepping away” from an overwhelming helping of information, the camera makes a series of cuts trucking away as Porky continues to scream and bang his gavel. Slowly, the viewer is introduced to more context piece by piece: the gavel, Porky, Porky in his robes, Porky in his robes at a podium, Porky in his robes at a podium in front of a crowd of people. Whether owed to these directorial maneuvers or the cacophony of his one man band, all eyes are decidedly on him…

…allowing for a polite, reserved “…eh-pih-please,” that proves equally deafening in its quietude to land most effectively. The difference in volume and demeanor is key to its success, but the addition is likewise an endearing, telltale piece of personality on behalf of Porky. His manners read as wholly redundant after his shameless display, but nevertheless communicates a concession, and acknowledgment of his decidedly uncouth behavior. His shouting and gavel banging easily negate any attempts to save face that stem with the “please”, but such is the glory of the gag: it isn’t uttered as a means to save face so much as it feels like a sincere compulsion.

Cutting in to a closer view allows for a more intimate glance of our magistrate. The camera is positioned at an angle that looks up towards him rather than directly at; such an angle offers an air of authority as he looks over the viewer. Inclusion of the podium in the foreground furthers such an illusion. That in itself mingles well with the lack of authority registered by his getup. Maintaining his bowtie is a wonderfully thoughtful design choice, as it grounds him back to the Porky we so revere. Or, in other words: no other court judge in their right mind would ever pair the affectionate chintz of a bowtie with the stolidity of judges robes. Obtuse inclusion of large spectacles pushes this sensation of “playing dress-up” rather than an earned obligation to a role.

Dress-up or not, he has the honor of introducing the very case in which this cartoon hinges on: Duck eh-vs. dih-de-eh-Duck.

It is then, through the courtesy of a shot from Porky’s own point of view, that Duck Development is made. Disguised through the overwhelming sea of the divorce court, Daffy sulking in his spot isn’t exactly noticeable until Porky calls him up. Aided by a music sting from Stalling, Daffy does a take, immediately guiding the eyes of the audience to him. Forthcoming shots capitalize upon his malaise more effectively, but such an understated start is almost an equally startling development in its own way. It’s been quite a few years—if ever—that a cartoon has delegated its introductory focus onto him with such nonchalance. Or, perhaps in this case, even armed with the intent of making him seem purposefully obscured within the background.

Momentary as this shot may be, its composition (visually and directorially) deserve praise. Placing the viewer directly in the eyes of Porky gives him a sympathy of sorts. He isn’t just a cold, steely mediator here to meet Clampett’s contractual obligations. Rather, he’s as much of a spectator as we are. His involvement offers a stake, too—after all, it’s he who bears the responsibility of striking the verdict. Sharing his point of view gives him a little more prominence to make his appearance seem less transparent, as well as remind the viewers of the stakes at hand. Divorce court isn’t a glorified story setting. Livelihoods hang on the line.

Daffy’s livelihood included. Thus enters a bombshell of a character introduction: trudging along to an equally sullen accompaniment of “Old Black Joe”, his slouched, knuckle dragging posture, his heavy, baggy eyes, and overwhelming moroseness are all entirely new. As of August 30th, 1941, nobody has ever seen Daffy Duck look, act, or behave in this manner.

Exaggeration of his lethargy lends itself to a comedic endearment just as much as it lends itself to concern. Every aspect of his demeanor is such a vast caricature within itself. He isn’t slouching, but barely dragging himself across the floor. His movements aren’t reluctant, but sluggish and restrained entirely, as if each step requires every ounce of physical effort he can sustain. Such an utter degree of hyperbole initially elicits a laugh from the audience—even if it is quick to trail off into a handful of uncomfortable, strained chuckles that dissipate entirely upon the realization that something is terribly wrong.

Obviously, context is key. Perhaps retaining his usual chipper demeanor would be a more startling alternative in a short whose title is “The Henpecked Duck”. Compensating for the demands of the story is necessary, but that nevertheless doesn’t negate the novelty of the opening. Owed to a steady, conscious evolution, he has experienced emotions other than blind insanity. Pride. Vengeance. Fear. Humility. Duplicity. Sympathy. Some examples are more sincere than others (throwing sunglasses on a befuddled hunter Egghead and declaring him blind as a reflection of his poor shooting skills, muttering “Too bad… too bad…”, for example, may not be the most genuine expression of condolences), but a steadily expanding cognizance has lent itself to a broader, fuller duck.

Cognizance is exactly why this introduction makes the impact it does. We have never seen him so utterly downtrodden and sapped of energy—this is clearly owed to a reaction of some kind. A reaction that communicates an awareness. He’s exceedingly aware of the conditions of divorce. That in itself likewise informs a sense of guilt; he seems to have resigned himself to his fate. Acknowledging that there is a fate to resign to begin with is pretty telling.

All of this verbal expenditure is a very convoluted way to declare: Daffy has never acted like this before. Such lugubriousness, piteousness, and depression is completely alien to his character as we know him. In spite of the general sense of caricature in which these feelings are delivered, the underlying earnest and humanity is where the jolt stems from. No punchline or witty one-liner awaits on the other side. There isn’t a sense of business as usual. A chilling permanence hangs thick in the air.

Clampett capitalizes upon this all throughout the short in different ways, but one of the most immediate is through the visible ghastliness of the crowd. Dick Thomas’ background painting accompanying Daffy’s death march is washed out, blanched, uneasy; formlessness of the figures is all intentional. In spite of no visible construction of any facial features, the unwavering stare from dozens of unblinking eyes is immediately communicated. Unblinking eyes that all appear to be pointed right at Daffy. Such encourages a sympathy towards him as much as it robs him of it—all eyes on him could either be a comfort, as they recognize his slumdom and are liable to sympathize… or it could just as feasibly smother the already suffocated duck further. That if he were to make one wrong move, one wrong blink, one wrong breath, it would all be recorded by a witness.Revisiting Porky’s point of view now offers the benefit of Daffy peering apprehensively. Cutting off the lower half of his face and body subconsciously stresses Porky’s authority by having Daffy beneath him; obviously, the short doesn’t exactly hinge on this dynamic, seeing as it isn’t Porky who’s doing the henpecking, but his superiority as the judge is nevertheless an earned factor in making the story come together.

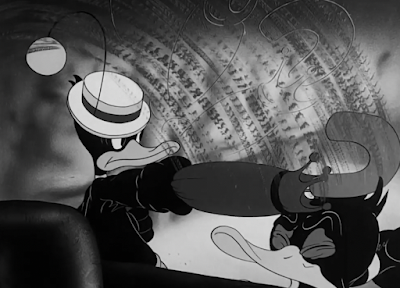

Moreover, relationship dynamics or hierarchies between Daffy and Porky are not the goal of returning to this shot. It instead seeks to usher a parallel. Wide shot, Porky calls Daffy to the stand, cut to Daffy trudging through the crowd. Wide shot, Porky calls Daffy’s wife to the stand, cut to Daffy’s wife trudging* through the crowd. Positioning Daffy in front of the podium offers its own means of foreshadowing; with his head cocked, his eyes point directly to Mrs. Duck seated in the crowd. Her own introduction flows more seamlessly through this introduction to an introduction, as well as shedding a little more light onto Daffy’s dilemma. He seems to be bracing for her approach—such subliminally instructs the audience to strap in.

Sure enough, Mrs. Duck’s introduction flourishes as a proud antithesis to her husband’s. Proud, pompous army fanfares to match her proud, pompous stance as she most decidedly does not *trudge through the audience. Duration of her walkabout is thrice as short as Daffy’s. Indeed, her stereotyping as the battle axe is clearly cemented and communicated. It is exceedingly obvious who wears the pants in this relationship.

Viewers are privy to a shot of each duck side by side for a mere second before cutting into the meat of the case. Barely any time is allotted to digest the new information before being thrust into the next idea—as haphazardly as this may read on paper (and, admittedly, a little on film), this too seems to be an entirely purposeful directing choice. The dynamic between Daffy and his wife thrives on parallels. A downbeat, pitiful Daffy with his slouched posture, dead eyes, a reluctance to do much as blink juxtaposed against the firm, motivated stance of his wife. If anything, her movement borders on excess—the wonderfully obtuse deely bopper on her hat gives way to some follow through and a settle long after she’s stopped moving. Her very presence and demeanor seem to hang in the air as a constant reminder.

Tangential as that scene may be, it is helpful in registering further incongruities and parallels, even at a subliminal level. Very rarely are the two of them on the same footing throughout the cartoon. The highlight being so fleeting almost seems to be a commentary within itself.

Cinematographic brevity is more accurately attributed to the histrionics that explode on the screen immediately after. The scene isn’t longer because there’s no time for it to be longer—a close-up of Mrs. Duck screaming “I want a divorce! I want a divorce!” immediately thrusts all attention and focus onto her. It’s almost as though she’s momentarily taken over the directing of the cartoon, as the filmmaking bears no choice but to give way to her protests. Between Sara Berner’s shrill, convicted, and wonderfully acted deliveries, the intimacy of the close-up, and the broadness of her gestures as she pumps her hands and leans into the foreground, steering any sort of focus away from her would be a fool’s errand.

Juxtapositions in demeanor even extend to character acting. Obviously, that sounds like a given—Mrs. Duck is uproarious, commanding. Her husband, in this startling new development, is not. However, there’s more to it than just that; Mrs. Duck’s acting is a reflection, a personification of her spiel. Mentions of “slavin’ over a hot nest” prompt her to sweat profusely. The crook of her umbrella winds around her neck as she tugs on it, indicating the metaphorical suffocation and strain that ails her so.

Daffy, on the other hand, barely moves. Barely. Barely moving still constitutes movement, and this in itself—the ever so slight, morose turn of the head—is more damning and humanizing than if he were to stay completely still. His idle turns of the head serve as a reaction; thus, the viewer knows he’s hearing all of her insults and names and claims. More sympathy unto him.

Especially given that Mrs. Duck immediately begins to clobber her other half with her umbrella. Spontaneity of the gesture and its corresponding name-calling (“You barnyard boob!”) could be grounds enough to laugh, but the maneuver again seems to be constructed with the intent of pathos and utter sympathy rather than humor. Ferocity of the sound effects, what with its echoing smacks, are compellingly violent and painful.

That violence is exacerbated through a comparative lack of reaction from Daffy. He responds to the thrashings, but not in the manner most would expect—no over the top verbal exclamation to signify his pain, or even an over the top visual pantomime to achieve the same effect. A stolidity remains for as much as one can be stolid when repeatedly getting thrashed by an umbrella. For a character as innately reactive as Daffy—a reactivity that inarguably transcends every possible incarnation of the character, a reactivity that is the glue to Daffy Duck—this is nothing short of startling. For him to behave so austerely, even in instances where the opposite is more then justified, indicates that something is seriously wrong.

Clampett rides on that wave of empathy by casting a close-up specific to Daffy’s reactions. Through this spotlight, more about their dynamic is illuminated than what would be the alternative of demonstrating more thrashings or elevated histrionics from his wife. Viewers instead watch as Daffy watches—how he flinches, how he sulks, how he peers out of the corners of his eyes, almost to ask as if everyone else is hearing what he’s hearing. His acting is once again conducted with a sobering concentration of humanity.

To see him flinch and cower not even at the threat of an impending umbrella, but the acerbic sting of his wife’s insults (“You fugitive from a featherbed! Well? Ya water-soaked weasel!”) proves yet again to be a remarkable development in his growth: he now has the cognizance to take offense to insults.

Obviously, this too a given. Insults are offensive. Soon enough, Daffy would undergo further transformation to take offense to implications that he deducts are an insult to him, regardless of their actual intent. However, up until this point, he’s retained an attitude of resilience even towards things that should offend him (Leon Schlesinger’s disinterested chain smoking as Daffy performs his heart out to him in You Ought to Be in Pictures, for one.) Depending on the time of the short’s release, some of it is plain ignorance, too wrapped up in the throes of his hysteria to care. Other times it’s a purposeful disregard, the “sticks and stones” philosophy. Even as recent as A Coy Decoy, he does take minor offense to Porky insulting his love life to his face (perhaps judging by how his love life is going in this cartoon, there was justification to Porky’s claims of Daffy’s inability to find a good match), but only through a pompous raise of the chin that flourishes as a proud topper to a gag rather than a sincere piece of insight to his psyche.

Solid draftsmanship in the animation and drawing of this sequence likewise give way to further empathy. Superficial of a deduction as it may be, it does often prove easier to sympathize with characters if they’re drawn or approached in a way that elicits appeal. Daffy certainly is appealing here, aspects such as solid construction and believable acting given heavy prominence to endear himself to the audience. For example, him flinching into himself prompts some extraneous follow through on his strands of hair; an additional aesthetic flourish that lingers on screen after he himself has finished moving, it instills a believability to his physics and reminds the audience that he is a living, breathing being whose parts move just like everyone else’s. It isn’t a static distribution of one drawing to the next, snapping from pose to pose to pose. In this moment, he isn’t a mere sequence of drawings.

Those who assumed the sanctity of a close-up offered sanctuary from parasol pummelings are soon to be proven wrong. Sound effects of the beating here carry a more tangible mischief to them (an echo of what almost sounds like a guitar string snapping rather than the all consuming, harsh snap of a WHAP) to subliminally lighten the tone, seeing as indulging too frequently in more realistic sound effects may only make the viewing experience unpleasant in a way not desired. It’s a philosophy Clampett himself has mentioned abiding by; the story of The Daffy Doc comes to mind, in which he lamented the realism in the sound effects for an iron lung over the preferability of a lighthearted alternative, citing that the auditory believability rendered the gag unpleasant and marred his appreciation of the film. That same toeing of the line—which sound effects to use when and where, and why—is applied synonymously here, to a surviving degree of success.

“Don’t stand there! Say something! Say something!” serves as the justification behind Mrs. Duck’s proddings and beatings. Daffy thusly obliges—the obtuse grin on his face may seem like an atonality, but that in itself is a product of Clampett’s directorial voice overriding Daffy’s. His wide, giant grin isn’t so much a reflection of his emotionality of mental state as it is a directorial commentary.

Depicting him all the more eager to say something, only for him to aggressively be shut down moments after exacerbates the brutality of his wife further. It’s all a maneuver to indulge in the titular henpecking: wife asks something, husband does as she asks (and so pleasantly too—what a dear!), wife screams at husband to shut up. Audiences everywhere laugh contentedly as thoughts of “Dames, amiright” resound in the heads of thousands. Suspension of Stalling’s musical orchestrations during the bear in which Daffy prepares to speak is likewise an inspired maneuver of sustaining tension all the more.

So, with Mrs. Duck firmly shutting up her husband, the way is paved so that she dominates the last tangent before going on. Repetitious screams calling for a divorce allow her histrionics to linger in the air and override any sensitivity felt towards Daffy’s case. This is still intended to be a lighthearted romp… in parts. Establishing Daffy’s emotionality and vulnerability is important, exceedingly so, but overdoing it can leave the audience synonymously miserable. Doses of pathos and sympathy are handled calculatingly.

A technical aside: the color card background remains the same for both scenes side by side. An economical maneuver, the reuse is disguised through the vastness of Mrs. Duck’s acting—one would have to go out of their way to notice it. As is being done right now.

Porky is now the chosen candidate to construct further directorial parallels; a camera pushing in onto him as he asks her to slow down feels somewhat redundant, as his acting doesn’t demand such cinematographic prioritization. Instead, it’s a means to an end: cutting the camera tighter enables the illusion of his own hands jutting off screen and into the foreground in broad, sweeping gestures… just like a certain Mrs. Duck moments before.

“Well, your honor… everything was goin’ alright until one day last week…” One wonders if this sentiment of “alright” is one shared by Daffy. An apprehensiveness seems to dominate that minuscule maneuver of his eyes sliding over. “I hadda go over to my mother’s, and, uh…”

Reprisal of the coiled iris wipe from We, the Animals - Squeak! dates this cartoon—not out of any sort of moldy fig archaism aging poorly, but more as an indication of Clampett’s pet directorial traits at the time. Creative transitions and means of segueing from one scene to another, for one. Like Squeak, the fantasticality of the shift is supported through Stalling’s ethereal vibe links.

Thus, the audience is formally invited to settle comfortably into the flashback that dominates the next four minutes or so of the cartoon. Clampett’s orchestration of the scene is already perfect: a number of cloying details beg the attention of the audience from the surface level alone. Most noticeably the giant “HOME SWEET HOME” cross stitch that dominates the composition, as well as an equally saccharine musical arrangement of the song with the same name. Such lengths taken to assert this as a happy, humble abode beg to be destroyed almost immediately. How could such a happy, domestically paradisiacal scene result in such a bitter divorce? Are Daffy’s actions truly reprehensible enough to completely destroy such a loving, intimate marriage?

Not quite. A handful of details are inserted to benefit Daffy’s case, if there is such a thing; when his wife instructs him to sit on “Junior” while she’s away, viewers will note that his silhouette morphs from that of a grin—supporting the meticulously bucolic setup of this happy marriage—into a very restrained nod. So restrained that he barely moves at all, but is more accurately reduced to a series of flickering drawings. A notable change in demeanor that seems to betray his smile; if that pleasantness happened to be genuine, surely his reaction would have been bigger.

Likewise, even the drippingly sweet cross-stitch on the wall seems to hint at forthcoming turmoil. Flower pots occupy the corners of the frame where the positive space of the typography does not. Two flowers seems to represent two figures—two figures make up a home. Partnership, camaraderie, etcetera.

However, the flower pot obscured by Daffy’s silhouette seems to prominently boast a flower that looks to be wilting. Its companion flowerpot boasts the same, but not to the same degree of exaggeration; that one has three flowers that are more evenly spaced in its sprawling, flowing arcs. The decaying petals that fit so snugly within the confines of Daffy’s silhouette distinguishes itself much more clearly than the single sad flower occupying the pot.

Moreover, a visible indication lies under that wilted flower that is not present in the alternative. A fallen petal. Given how comfortably the floral arrangement fits within Daffy’s silhouette, it doesn’t seem to be a stretch to deduce it as a representation of Daffy’s part in the marriage. That is, behind this image of sentimentality lies a wilting, faltering duck relegated to the shadows.

Especially seeing as Mrs. Duck is the first to break free from the cast silhouettes, strutting across the foreground. Granted, such is to communicate her taking a leave as well as support the elaborate staging, but an argument could still be made on its metaphorical importance. There is a sense of freedom conveyed through her exit (marred as it may be by some double exposure troubles with the camera)—particularly the way in which Daffy remains absolutely stagnant, chained to watch over the egg. Mrs. Duck, on the other hand, is free to revel in such privileges like visiting her mother or crossing the foreground.

Any allusions of disingenuous concordance are affirmed through her violent outburst: “AND IF YOU DON’T I’LL WRING YOUR FOOL NECK!” Albeit obscured through the frame of the cross stitch, Daffy’s silhouette has a break where his mouth is. That slightly agape expression adds the slightest bit of humanity to him. At least, much more than keeping his silhouette and mouth closed. The audience is reminded that there’s a real living being behind that projected shadow.

“Yes, m’love,” is the first verbal utterance from Daffy nearly two and a half minutes into the cartoon. This, too, is a major first. Contextual demands are again important—of course he’s not going to be yakking up a storm in the divorce court—but that quietude requires a certain restraint. Even if he’s forced into said restraint (as evidenced through his wife demanding he shut up after demanding he speak), there’s something to be said about his obedience to that reticence. Had this short been released a few years prior, it’s exceedingly likely that he wouldn’t have been sane enough to deduce that was something expected of him.

Allusions to Daffy’s folderol (“Remember now, none of your nonsense!”) are grounds for ponderance. Given the laborious architecture of Mrs. Duck’s legacy as a browbeater, Daffy’s “nonsense” may very well just be himself. On the other hand, given how rowdy and exuberant of a character he normally is, perhaps there is a shrapnel of truth in her claims. Not enough to justify her spousal abuse, but enough that constructs a story, a “behind the scenes” look that renders the story more believable.

Enter another close-up as tonal focus makes its way back to Daffy. Mrs. Duck’s goodbyes—if one were to ever consider her demands and warnings a “goodbye”—are now secondary, a means to shed light onto Daffy’s reactions and emotions. The frown that paints his face as she maintains her “Now listen you”s is a viscerally candid reflection of how he really feels about these affairs. Timing on his frown is sharp, believable, smooth through constant movement. Not that constant movement constitutes good animation, but it compensates for the stagnancy of his movements that so dominated the cartoon earlier. Stretching his frown just a bit further, further, further, his head continuously tilting down, pitiful blinks from his sad eyes, all of those behaviors remind the audience that Mrs. Duck’s berations aren’t going unheard or unprocessed.

“You stay in the house and keep that egg warm!” is her final say on the matter. A warped camera angle almost adjacent to a fish eye lens (seeing how the composition is somewhat blown out to accentuate and curve around Mrs. Duck’s presence) conveys unease and undivided attention through its dynamism. Especially for her slamming the door—having the door skim across the foreground as it sweeps to a crashing close catches the audience in the crossfire as well, seemingly placing them mere inches away from her wrath. This short is nothing if not immersive.

One final “Yes, m’love” from Daffy, even after she’s out of earshot. It’s been conditioned into him. Despite the door slamming closed and her making a final departure, he still finds it necessary to play it safe. Her henpecking is ingrained… but not to a degree of complete complacent apathy, either. Clampett allots just enough room for her bullying to still sting ever so slightly—just enough to give room for further reaction from Daffy, rendering him all the more sympathetic. A change to a different color card with slightly heavier values and shadows to it seems indicative of such bleakness.

Except… that final “Yes, m’love,” doesn’t prove to be final at all. Daffy spares another as the camera cuts to a wider shot, his expression visibly more candid.

“Yes… m’love… yes, m’love, yes, m’love—YES m’love, HOOHOO! yes, yes, yes, YES m’love!”

Catharsis. Catharsis for Daffy, and catharsis for the viewer. This outburst, this concession of a boiling point is a glimpse at the Daffy we’ve all come to know and love. He’s still impulsive, he’s still reactive, he’s still got that burning, almost violent urge to relieve whichever abreaction of the day broils within his insides.

In spite of such drastically different contexts (whether on account of the short’s story or the rapid growth and development Daffy has undergone in the near 3 years since), this exact boiling point is the very same “breakout” philosophy Clampett mentions utilizing in shorts such as The Daffy Doc. If everything is hysterical and crazy, nothing is. Screwball antics don’t land if they’re the default. Instead, a gradual, climaxing crescendo—seeing Daffy lose each one of his inhibitions in real time, watching as it gets harder and harder and harder for him to remain under wraps, like he knows he has to behave accordingly but just cannot help it for the life of him, he has to get it out, it’s not a natter of “if”, but “when”—all of these developments amount to an eventual breakout that is as cathartic to the viewer as it is to Daffy.

Even then, his performance here doesn’t entirely fit within the vein of “screwball antics”. The jubilant “HOOHOO!” that is let loose is much more akin to a Freudian slip of sorts, this verbal personification of that release that he just has to get out than it is so much a conscious attempt to paint him as a lovable, hysterical loon.

Albeit a word tossed around frequently in this review (which will likely continue to be the case), there’s a very urgent viscerality to his catharsis here. It doesn’t feel manufactured. It isn’t an obligation to Daffy’s roots as a—the—pioneer of animated screwballs. Instead, it’s a very raw reflection of his emotional and mental state.

Audiences who assumed his silent, steely, restrained subservience was too good to be true are absolutely correct. This scene exists to affirm all of the notions and preconceptions and worries and speculations on what Daffy has been feeling, and why, and how for the past almost three minutes now. His purgation doesn’t only come as a reward to him, but to us as well. The entirety of the cartoon has been building up to this moment. In a way, the audience is made to experience the same exact high and adrenaline that pumps so viciously through Daffy now.

Even then, it’s only received through a mere glimpse. Clampett thrives on the viewer-Daffy continuum by placing them directly in his point of view—thus, the sudden entrance of his wife barking “WHAT’S THAT?” is all the more shocking. Once again, further sympathy is garnered as the viewers aren’t made into witnesses, but recipients of her same wrath. The desire to root for Daffy—to be able to freely indulge in these catharses—only grows stronger.

Resuming his role as the kindly subservient husband unfurls in a matter of mere seconds. No hesitation of any kind dominates his loyal return to the nest—no aimless scrambling, no hesitancy. Even the grin on his face is almost instantaneous. Once again, Stalling’s musical orchestrations are halted, the silence hanging thick in the air to orchestrate further suspense. It’s almost as though even the hands that made this cartoon are reluctant to act on their obligations for fear of Mrs. Duck’s wrath.

The following “Yes, m’love,” uttered by Daffy is delivered more carefully, slower, thoughtfully, both to juxtapose against the rapidity of his exclamations prior and to assert that this time he means it. Maybe.

One intriguing background detail to note before moving on: a table and set of chairs flank the wall in the background. The rightmost chair is positioned noticeably further away from the table than the left; Daffy zipping back into the nest demonstrates that it’s more a means to occupy the negative space left in the curve of his body, which forms a perfectly tidy frame. However, one could also choose to interpret it as another bit of insight into the Duck household’s love life (or lack thereof.) Being married and living together implies they eat together too, which is surely its own can of worms—who’s to say Daffy isn’t one to attempt keeping a reasonable distance at the dinner table at all possible.

Most likely, its positioning is just a means to fill up the composition, but the thoughtfulness in the wilting flower cross stitch doesn’t rule out these design details being as thought out as they are. That such room is left for interpretation to begin with is a testament to Clampett and Warren Foster’s storytelling sensibilities.

Another reuse of the door slam shot for good measure. This short isn’t immune from its bouts of recycled or repetitive animation, but Clampett’s application feels exceedingly thoughtful in its economy. Or, at the very least, more thoughtful than what can often be the norm in his cartoons. Seeing as this scene is namely a jumping off point to a new sequence with new ideas and narrative tones, there isn’t an exceedingly high demand for a grandiose, visual spectacle. Getting Mrs. Duck out of the house at all is more important than why or how she leaves. All of that was established previously.

With all of that out of the way, narrative focus is delegated to demonstrate how Daffy copes with his responsibilities rather than if. There’s no room for argument: he’s to sit on that egg whether he likes it or not.

And, as evidenced through a 20 second segment focusing on his palpable discomfort, he falls into the latter. This too is executed with an underlying sympathy; his expressions as he sits on the egg and struggles to make it more comfortable aren’t resentful, ireful, vengeful. Instead, they’re pitiful. Especially with the wince that stems after repositioning himself, the audience is inclined to feel sympathetic for him.

In spite of being such an admittedly trivial predicament, Daffy’s point of view is still argued for. To him, having to sit in one place for who-knows-how-long just by itself is strenuous. Adding a large, obtrusive, uncomfortable egg to the equation renders it torturous. For someone who is so reliant on constant stimulation—whether it’s sourced from himself or an external factor—and likewise serves as a natural born contrarian (even if accidental), having to remain chained to such an obligation is genuinely hard on him.

Much of that empathy instilled by Clampett derives from a clear effort on Daffy’s behalf. There’s obviously a devotion of some kind—repositioning himself to be more comfortable communicates a commitment, trying to make the situation more pleasant for such a long haul. However, Daffy is still Daffy; a slow burn of indulgence creeps along as viewers can witness the gears turning in his head. Discomfort and pitiable malaise at the prevailing conditions slowly morphs into hesitant curiosity.

Pacing of the sequence succeeds greatly at conveying this crawling gratification. A pause between sitting on the egg and standing again is more fleeting the second time around than the first, with the second bout of standing lasting longer. There’s an organicism to operating in such increments; it’s a personification of this desire to disobey, this desire for “self preservation”, this desire for any sort of stimulation or comfort or pleasantry, this desire gradually sinking its fangs into Daffy’s being. He’s really trying to be the subservient incubator of his wife’s wildest dreams, but that impulsiveness and indulgence that so rules his character on all fronts is inescapable.

Perhaps Daffy Duck is not entirely of sound mind to be minding a baby.

Violently jostling his baby (with maraca sound effects to boot, giving a permanence to the gesture and a playfulness just the same) leads to a shrug. A shrug that is directed explicitly to the audience.

This seemingly throwaway gesture opens a Pandora’s box of the short’s appeal that’s been letting its contents leak slowly throughout the past three minutes. Part of The Henpecked Duck’s charm and appeal—at least, to me—is how vicarious of a cartoon it is. Viewers are made to feel included in the actual realm of the cartoon. Sometimes they’re a bystander peering into the divorce court. Sometimes they’re judge Porky Pig, sharing his field of vision and riding his wave of authority. Sometimes they’re Daffy, just as much a recipient of his wife’s wrath as he himself is. There’s a constant, rotating shift of view points, but all of them throw the viewer directly into the short one way or another.

And now, all of that is acknowledged by Daffy delegating his attention to us. That eye contact, that shrug, that concession of a gesture all cement that we are right there with him. Such vicariousness will play a pivotal role in the next few minutes, hence all of the scrutinizing and expatiating over a deceptively menial comedic beat.

Daffy’s lack of inhibition prevails after an agonizing 25 seconds. Rotating the egg and revolving it around his fingers is a much more pleasant task than having to sit on it—there is no plausible way for it to get warm this way (never mind the active danger posed by this activity in the first place; if violently shaking the egg and essentially scrambling any incubating brains within isn’t an act of child endangerment, this most certainly is), but he’s at least maintaining his duty of staying at his post. He hasn’t left the nest. Wifey can’t blame him for that.

A close up of this joyously ignorant ritual cements the irrevocability of the maneuvering—indeed, this is a real thing that is happening. Musical orchestrations are airy and light rather than tense and suspenseful; that, in conjunction with Daffy’s almost disingenuous humming, indicate that there isn’t too much a cause for concern narratively. If the egg were seconds away from cracking, surely the filmmaking would reflect that in a more salient way. Regardless, there’s just room for doubt that keeps the audience politely on edge.

Particularly when Daffy crushes said egg between both of his hands.

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment