Release Date: August 30th, 1941

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Chuck Jones

Story: Rich Hogan

Animation: Bobe Cannon

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

By 1941, the Curious Puppies were a relic of the past. Chuck Jones’ directorial abilities and sensibilities have widely expanded since their debut in early 1939; his cartoons are comparatively more abrasive, more quick, channeling his indulgences in different ways. Characters like Sniffles and even Inki have proved to be more suitable stars for his needs, allowing him to experiment and push and grow more freely than what is offered by the Pups, whose Disney influence is practically inescapable.

Even then, there is a novelty to seeing such a representation of his directorial history plopped into a relatively faster, seasoned environment. The second to last cartoon in the Curious Puppies saga, their bone chasing antics now take them to a winter wonderland, where the scenery proves to be just as troublesome as it is gorgeous.

Right off the bat, the cartoon fades into an open with two of its most notable stars: Paul Julian and Carl Stalling. Julian’s backgrounds are illustrious through and through, the plethora of white snow no obstacle in ensuring the backgrounds read colorfully, coherently, and engagingly. Likewise, Stalling’s musical orchestrations are a joy to listen to, opening with a playfully frenzied romp of “The Sidewalk Serenade”. These two are the most responsible for any of the cartoon’s successes.

While that may paint a foreboding picture of desultoriness—if the greatest point of interest lies in the music and backgrounds, then what does that say about the story or the characters?—the opening of the short itself does prove to be one of the most engaging aspects of the cartoon. Whereas Stage Fright opens with the two pups fighting over a bone, soon to engage on their chase, Jones wastes no time with such formalities. Starting with the pups running over hill and dale automatically engages the audience, as it implies a story, a “behind the scenes” that bestows the illusion of depth to the cartoon.

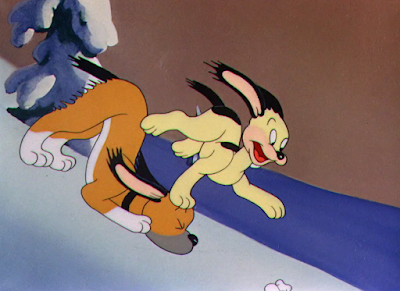

In the flashes that he passes by the camera, historians may note that the little pup has received a slight redesign. Instead of maintaining his usual coloring of white fur, his coat is now a gentle cream: it should be noted that this is the only cartoon to do so. Likely, the change seeks to accommodate the setting—white fur on white snow would grow distracting to keep track of and potentially lose clarity. Especially during long, expository chase sequences, where the characters regularly zip in and out of background elements to give the environments some dimension.

Indeed, the chase is very well executed. Teetering on the more domestic side, as a juvenile mischief serves as the prevailing tone (as opposed to the adversarial tone in Stage Fright or the anxiety of the pups being chased by a dog catcher in Prest-O Change-O). However, there is no narrative need for an excessively tense mood. The audience is encouraged to luxuriate in the backgrounds and depth of the surroundings, as well as become hypnotized through the surprisingly stable twists and turns and truck ins and outs of the camera. Channeling any sort of aggression would likely detract from such measures.

Their romp leads them to a ski jump, which offers an opportunity for Jones to channel his inner Disney through a faux multi-plane pan. Foreground elements move at a different rate of speed than the background, creating the illusion of dimensionality and supports the idea that the pups are genuinely interacting with their environments. Such a steep angle at which the composition is arranged does wonders in accenting the intended dynamism.

Likewise, the repetition of these pans and twisting camera moves lull the audience into a trance of sorts, so that the sudden halt heeded by the littlest pup comes as a palpable surprise. Joyous musical orchestrations melt into a tense, brazen sting as the pup barely avoids toppling over the edge. Movement on his ears as he settles to a stop teeters on the excessive side, reading as though he is purposefully rotating them around as opposed to a natural, physical reaction of screeching to a halt, but remains ultimately harmless.

Focus is moreso delegated to the dizzying drop from which the pups loom over. Guidance of a slow, creeping camera pan renders the heights all the more extreme—the full extent of the descent can’t even be captured within the confines of the screen. Realism in Julian’s backgrounds, as well as the variation in hues and shadows do wonders to cement the threat of the fall. Jones would reprise a similar—albeit more frank—layout in his Two Scent’s Worth 15 years later.

Instead of focusing on a belabored scene of the pup turning around, carefully attempting to maneuver himself to prevent any slips or spills that could result on disaster, Jones once again favors a more abrasive alternative: have the Boxer pup knock into his companion, sending them both flying.

Pacing the animation and camera so that the pups gradually gain speed is certainly a thoughtful consideration; the gravitational pull of the slope can be felt, a more believable application of physics allowing any conflict and raising of the stakes to read organically rather than forced or convenient. Regardless, the “slow periods” are a bit too slow—the pups, their movements, and even the pull of gravity all seem to momentarily freeze in place. Keeping the camera at an idle crawl somewhat disguises the lapse in momentum, but a disconnect between the intended line of thinking and the product of said thinking nevertheless persists.

Keeping the bone in the shot as it, too, is a passenger of the slope reminds both the audience and the pups of the stakes at hand. Whereas the short began with the Boxer chasing the little pup for his bone, both dogs have now been shunted to the same rung on the ladder: thus, more interest is garnered as to where the chase will lead and how.

Even if matters of actually jumping the slope come first. Jones conveys the idea of going over the hill rather than actually conveying it. Instead of animating the pups sliding off, the earlier establishing layout of the ski jump is reused, with the camera zooming in and panning up to convey the sensation of being lifted up. It probably would have been more convincing to demonstrate the pups actually being thrown off, as it does read somewhat transparently as a camera trucking in on a still painting, but the economy and creativity of such a decision is commended nonetheless. Of all the possible workarounds to avoid animating the pups, it’s one of the most logical.

Particularly because the conveyance of the pups sliding off the slope boasts a greater spectacle than the actuality of them flying through the air. It, too, is just another piece of regular business, the pups observing with relatively neutral expressions—such maintains the playful, perhaps domestic air of the entire chase, but does seem to demand a larger reaction given how stressed the height of the drop was. Having the littlest pup attempt to catch the bone in the air is nevertheless an inspired choice; once more, the audience is reminded that there is a driving force behind such antics.

An overhead shot of the bone falling to the ground—with two puppies shortly behind—is greatly benefited through the inked shadows that track the objects. Such gives the composition a sense of depth and scale, indicating to the audience just how high in the air they are. Likewise, pointing the camera straight down directly immerses the viewers themselves in the action; they, too, are made to feel as though they’re toppling over the edge.

It’s the Boxer who lands closest to the still sliding bone, rather than his pup companion. Thus, the tables are turned, again attempting to keep the audience engaged by truly conveying the feeling of a race. Viewers will note that the Boxer is drawn with tiny fangs as he opens his mouth to grab the bone—a first compared to the human adjacent teeth he often touts.

Riding the philosophy of a neck-and-neck race, the pup manages to climb over the Boxer and gain the lead. Just in time for the slope to even out and launch the dogs into new, untraversed territories.

Like this fresh snow mound.

Those wondering about the positioning of the bone as it suddenly resides next to the pup instead of front of it are answered by the arrival of the Boxer. A cute and clever silhouette gag that makes the most of its surroundings—an aspect that comes and goes with these Curious Puppies shorts and their ever rotating selection of backdrops. Even this one.

Now, the chase lands the pups right on the ice: the majority of the cartoon shall be spent in this location. Paul Julian’s background paintings deserve continuous credit, as differences in texture and hue between the ice and snow are very much communicated. Likewise, the warm, rose-orange glow of the sunset offers a strong juxtaposition of color that renders the snow all the more cold in comparison, with all its hues of white and blues and purples. Every little aspect and detail—even those that are inclined to blend together, like the ice and snow—reads not only coherently, but strikingly so. Foreground elements passing at a slightly different rate of speed than the background really do wonders for making the environments feel believable, dimensional and interactive.

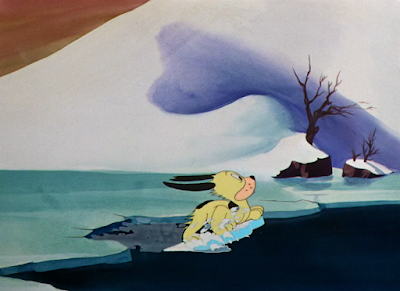

Carl Stalling is a continued hero as well. Maintaining the same score of music for over a minute now, he interjects slight modulations and tempo changes in the music to account for any differences in environment. As the pup is first seen sliding on the ice, the music notes are held together in a continuous legato, as though even the song itself seems to be sliding along without any breaks. A surprised take is briefly reflected in the music (though still grounded to the melody), and the suddenness of the pup riding a broken piece of ice across an exposed stretch of water heralds a somewhat more circuitous, “wavy” flourish that succinctly captures the unsteady rush felt by the dog. These little changes make a huge difference, giving each action a sense of independence and allowing it to read as something other than a string of incidents to keep the audience engaged.

Even if that is essentially what the short devolves into—such is the vice of the Curious Puppies format. Like all of the shorts in the series preceding this one, the cartoon splits into two sections: the whereabouts of the littlest puppy, and the whereabouts of the Boxer. Both carry on with their respective antics until both storylines eventually converge, which is a privilege often saved for the climax. Having the ice stagnate and pup struggle to get off said stagnant ice chunk indicates that this will serve as a recurring point of focus.

Meanwhile, the Boxer—albeit barely—skids past the exposed ice. Stalling’s musical orchestrations seem to illustrate more than what actuates on screen; the backing track rises into an alarmed trill at a seemingly random point in the animation. That is, there isn’t any animation on the screen that matches such a purposeful urgency in the music. It almost sounds as though there was supposed to be a startled or scrambling take of sorts, as if the dog was trying to scramble away from the rapidly approaching water, but a lapse of some kind—altered plans at the last second, not enough time, or plain miscommunication—prevented it from being so.

Cutting to a beaver contentedly finishing its dam (never mind the dam being entirely on top of the ice, exacerbating its redundancy without a steady flow of water even further by being out of reach from the water when it melts) reassures the viewer that those efforts will surely destroyed with the impending threat of a dog.

That is indeed the case. Bowling sound effects serve as a logical accompaniment, stressing the severity of the impact while giving it a mischief all the same.

Perhaps somewhat shoehorned, Jones inserts a shot of the beaver reacting to the obliteration of his hard work. Jones’ line of thinking is easy to see: keeping the beaver in the picture ties a slight emotionality to the whole gag, hinting that this was the product of some hard work that he now has to restart all over again. It prevents the collision from reading as a transparent means of comedic filler. However, it does seem awkwardly inserted into the action—or, at the very least, not gratifying enough to warrant the intense close-up it maintains. If he observes in nonplussed shock, that’s fine, but a whole new layout just for a few seconds of empty gawking seems extraneous. If more time was delegated to concocting a greater reaction—perhaps he grows mad and curses intelligibly at the dog—that would be different. Either way, why it exists in its current form is easy to see. Just that there seem to be more efficient ways of conveying a similar point without the same accidental awkwardness.

In a way, the gag is built upon… just not from the beaver. Sticks and logs have configured themselves to form a tipi around the Boxer as he keeps sliding along; the slight wavering in the sticks as the momentum is maintained is a very conscious little touch. Jones would have been fine if the sticks and even dog remained on a static layer, with the camera and moving background pulling all the legwork, but that quest for believability and visual splendor, even in the most minute of details, comes in clutch.

Similar praises are due for the organicism in which the tipi falls apart. Rather than a simultaneous crash, disassembly is staggered to maintain that sense of realism—or, at the very least, as much realism that is allowed with a dog sliding out of control on the ice in a makeshift tipi.

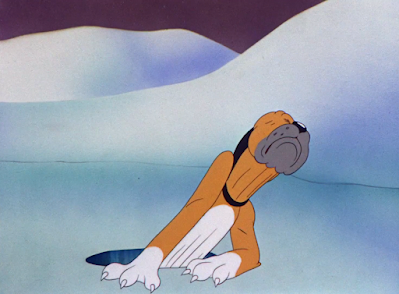

Likewise, somewhat resistant reactions to a growing mound of snow as the dog reaches the end of the pond are similarly organic in their animation. His polite disgruntlement—subtle as it may be in the long run—does give a tangibility to the snow, making it seem all the more thick and obtrusive than if he were to just slide into the snow with that same nonplussed expression.

Effects animation on the falling snow once the Boxer collides with the tree is sophisticated, organic, and attractive. Again, Jones prioritizes moments of economy when he can: the sense of the dog hitting the tree is enough for the needs of this sequence alone. Viewers don’t require a play by play of the Boxer visibly hitting the tree to understand that there has been a collision. A collision that, likewise, marks the end of his ice capades. For now, at least.

Brief entry of an innocently perplexed squirrel serves as a mirror to the equally mazed beaver. Woodland animals reacting to the result of these playful antics again gives a pathos to said antics—the dog crashing into the tree carries more directorial weight if someone (or something) makes a direct acknowledgement of it.

Colliding with the tree does prove to have long lasting side effects, justifying the additional focus from the squirrel. Our Boxer friend is now thoroughly punch drunk: bad news for his attempts in snagging the bone.

Granted, the actual depiction of his dazed stupor occasionally suffers from bouts of ambiguity. Stalling’s drunken, razzing music score is enough of an indication in itself, as well as piecing together the inevitable. Who wouldn’t be dazed after a hit like that? Regardless, the dog’s initial exit from the snowbank doesn’t immediately register as stuporous. Grawlixes shot on a double exposure circle his head after he trips on the ice, erasing any room for doubt—such a benefit could be used at the top of the scene, where the pup appears overconfident and content rather than stunned.

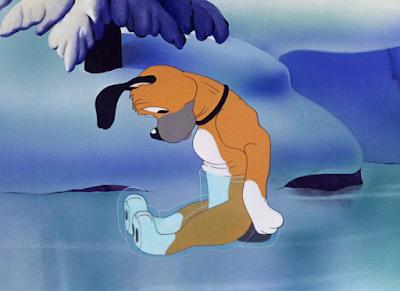

This entire charade is a reprise from the last Curious Puppy short, Stage Fright, which had the littlest pup in the role of the Boxer. Thankfully, the sequence here is much less cloying than its predecessor, even if the intentions of the predecessor registered more quickly. Both shorts tout a shot from each dog’s point of view, staring at the bone from a warped, blurry line of vision. Both shorts likewise use a ripple glass effect upon the initial registry of the bone; it’s a convenient shorthand and communicates what it needs, but it does seem that there could be more convincing means of conveying that hindered vision (such as multiples of the bone shot on a double exposure or unscrewing the camera lens in front of the aperture to give an out of focus, warped spinning effect.)

A giant, toothy grin on the Boxer also feels incongruous to the prevailing tone. It’s amusing, and such a goofy expression certainly could be owed to his dazed state, but it reads as an additional tangent, an entirely separate idea thrown on top of a completely separate sequence. The expression itself seems to be borrowed from 1939’s The Curious Puppy, in which both pups engage in a “mirror routine” a la Duck Soup. Perhaps that is where the notions of incongruity stem from.

Falling into his feet likewise reads as a rather purposeful gesture than an accidental byproduct. It’s as though he purposefully propels himself off of his feet, jumping into the air and landing on the ice; the energy is considerate, but sequences like these are best played subtly and grounded—at least, as far as accidental slips and falls go.

A repeat of that same bone shot with the same ripple glass, adjusted only for the bone to be closer to the dog.

Even if that in itself proves to be futile. Adjusting the distance of the bone to account for the distance traveled is a considerate acknowledgement of how the environments are being utilized; in the long run, however, it doesn’t exactly mean much if the dog runs and slides across the ice for a total of 15 seconds after the fact. Given that the close-ups imply how close in proximity the bone is to him, there comes a strong disconnect.

However, a gust of wind dragging the dog backwards provides some answers; the effect of him being forced across the ice and bank into the snowbank doesn’t read as clearly if he’s dragged only a few feet rather than a few yards. Regardless, the close-ups of the bone do feel as though they should have been constructed with this distance in mind.

As for the wind itself, some airbrushing or any hand drawn indication of the wind blowing would certainly prove to be a benefit. Hollow blowing sound effects convey the forces of the wind adequately, but it does seem as though the dog is being pulled along the ice through a magnetic force of some kind rather than succumbing to a convenient breeze.

Thus, he ends right back where he started. Confused squirrels and all.

Elsewhere, a return is made to the littlest pup, who still finds himself stranded on the piece of ice. Stalling’s musical choice of “Keep Cool, Fool”, is a cute, literal commentary that maintains a flightiness through its flutes to match the diminutive stature and demeanor of the pup. Such a deduction applies to almost every one of these cartoons—not just this one—but one does ponder just how these cartoons would fare with a less attuned and by all accounts brilliant composer. Shorts that are reliant on his music cues for entertainment and coherence (like this one) would be likely to have any and all flaws exacerbated without such a support system.

In fact, the music seems to be the pup’s only support system, as the ice continually snaps beneath his paws. Attempts to steady himself grow increasingly futile, as the ice continues to snap into parts like a frozen matryoshka. It’s polite and it’s cute without feeling utterly forced, and certainly a much better alternative than repeatedly cutting to the pup coping with the chunk of ice melting or submerging beneath his feet. More visual interest is always welcome.

As is, perhaps, more steady directing. While checking in on the little pup is a must—such is the nature of these shorts with the diverging storylines, as well as to keep the audience engaged—said check-in barely feels like it started before the camera dissolved back to that ever familiar snowbank. Granted, there’s only so much one can milk out of the ice snapping beneath his paws, but there does seem to be a disproportionate amount of time delegated between both dogs. This will of course change as the cartoon chugs along, but nevertheless, an imbalance certainly seems to persist for the time being.

It’s likely that such a critique is more a commentary on the Boxer’s antics feeling so utterly repetitive; visiting an idea that isn’t circuitous running back and forth across the ice or hitting into trees is sure to be a relief. Then, when it’s paid its dues and the antics settle back to more of the same, a sense of an anticlimax is only natural.

Nevertheless, the Boxer rushes towards his bone once again. A cut in on his face reads as particularly arbitrary—the action doesn’t intensify or even change to warrant such a sudden jolt of attention. On the other hand, that could precisely be its intent. Such a change in camera registry facilitates a change in tone, no matter how subliminal; thus, perhaps the audience is meant to be convinced that the action on screen is more titillating than it actually is. After all, the camera is devoting its full attention. Surely that means we must do the same.

Jones continues to get a lot of mileage out of that single distance shot of the bone. Here, a lack of ripple glass obscuring the scene is liberating on behalf of the dog. Closer and closer, the bone is in his clutches. No wind gusts or tree collisions can detract from his goal now.

A lack of aim and out of control speeds, however, can.

And, as one may guess, that lands him directly into yet another beaver dam. This short falls into one of the strongest vices of the Curious Puppy shorts, and something that was touted excessively in Dog Gone Modern: repetitious topper gags that are amusing only to the hands that made them. The first occasion or two may rise a polite chuckle out of the audience, but the exact same gag with the exact same footage is reused over and over and over again with hardly any variation in the outcome or punchline. There’s no sense of mystery or subversion—everything is exactly how it looks like. Thus, antics of the cartoon grow even more stale and tired than what may be the case normally through this futile shoehorning.

In other words: we’re going to be seeing this beaver dam a lot. Ditto for the bewildered, stilted reaction shots of said beaver that follow, all utilizing that same head turn. That the beaver turns his head in a different direction to account for the shift in stage direction is about as subversive as the punchline will ever get.

Thankfully, Jones had enough sense not to repeat the same outcome as last time. Now, the Boxer finds himself the recipient of a perfectly constructed log cabin instead of a tipi. His befuddled, cloying blinks at the audience communicate a self awareness of the repetition—something that could stand to go further than it does.

Likewise, the cabin slides out of view and away from the dog rather than breaking into pieces. That is owed to the convenience of an ice fishing hold carved in the pond; this, too, will be a harbinger of further ice themed antics.

Visceral facial expressions has been a relative blind spot for this cartoon; some of the Curious Puppy shorts channel more human, visceral, and amusing emotions than others. Sometimes they can read as cloying in excess, but do serve as a strong antithesis to the cuddly, decidedly domestic nature of the dogs. The strained grimace reflected on the Boxer’s face here is one of the most amusing footnotes of the short. It’s a shame that a cross dissolve to a new scene is so quick to cover it up.

Thankfully, animation on the pup patiently observing as he slowly glides along on his singular ice chunk is some of the most solid and well constructed in the short. Stage Fright boasted some particularly well sculpted, tight shots that were certainly helpful in giving the pups charm. Jones’ directing has grown a bit more snappy, loose, and flexible in the year since—as such, these tight shots of meticulous construction aren’t as prioritized as they once were.

Here, a solid distribution of both is achieved. The comparatively newfound zest and snappiness (for 1941 Jones standards, mind you) found in Jones’ recent slew of cartoons is manifested through the dog scrambling to the the of the ice once in reach, movements limber and loose to succinctly convey his excitement. Construction is comparatively tight and drawings more solid for the more “stolid”, down to earth beats that follow—the pup investigating a growing fracture in the ice, for one. Carl Stalling marks all of the movements and shifts in speed through the appropriate flourishes, or lack thereof.

Yet again, his involvement is not taken for granted. Shifting the tempo of the music (still “Keep Cool, Fool”) to match a shift in walk cycles as the dog attempts to escape the crack again sustains an individuality and memorability to each of his movements. His rapid, almost galloping tip toeing is able to juxtapose against cautious crawling backwards; both of which contrast against the eventual running start as the fissure grows bigger and bigger. Running speeds of the pup could stand to be less glacial, and one is left to ponder how he is the one to prompt such a drastic crack in the ice (as opposed to the much larger Boxer with all of his repeated galumphing), but the scene is well executed otherwise.

.gif)

.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment