Release Date: June 27th, 1942

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Friz Freleng

Story: Mike Maltese

Animation: Gerry Chiniquy

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Dog, Rooster, Cat)

(You may view the cartoon here!)

Mike Maltese and Friz Freleng continue their partnership through another effort pertaining to one of Maltese’s pet genres: a subversion of the chase cartoon.

Double Chaser may more accurately be dubbed Quadruple Chaser—and even then, that may be exclusionary, as at the cartoon’s zenith, the idea of an organized chase delves into complete chaos. Dogs chasing cats chasing mice, with cats periodically chasing chickens, with the mouse wanting the dog to chase the mouse in order to chase the cat, and so on and so forth. Maltese would revisit the same setup (albeit more methodical in establishing its hierarchy) with Chuck Jones’ Fair and Worm-er, released 1946; after all, it’s his dabbling with these cartoons that the Road Runner shorts owe their existence. Those, too, were initiated as a deconstruction of a typical chase cartoon.Maltese’s love of chase psychology benefits the purposes of our dissection here, as we now have a direct means of comparison to juxtapose both his and Freleng’s artistic growth. Comparing Double Chaser to its informal predecessor, The Cat’s Tale, yields a world of difference and growth that is pretty staggering for just a year. Character designs, pacing, cinematography, convolution of the chase itself have all been refined to the nth degree. In spite of Chaser’s admitted innocuousness today, it does provide an enlightening glimpse at just how quickly the Warner style of cartooning was solidifying into what we know it as today. That is why it feels so innocuous from a modern perspective—what is now aggressively standard for these cartoons once had to be engineered to be the case.

With that, we segue into our next deconstruction of the chase cartoon. A cat wants to chase a mouse, who weaponizes a dog to intimidate the cat; as the cat grows more persistent (and, in the presence of the dog, desperate), more elements are added before devolving into a whirlwind of animal hierarchies.For a cartoon that is soon to delve into utter convolution, its opening moments illustrate a deceptive calm and domesticity. Carl Stalling's music is light, airy, still, the lighting and values of the background painting soft and warm. Little details such as a stovetop with its oven door open, chairs and stools strewn around the kitchen, a butter churn in the connecting room and a pump render this farmhouse lived in and loved. A far cry from the dog eat cat eat mouse world soon to explode out of and around the house.

Whether intentionally or otherwise, there's a bit of foreshadowing to another 1942 Freleng effort lurking in this layout. The manufacturer of the oven is labeled "Daisy"--the same source of metal that is synonymously branded on a statue of a dog in Ding Dog Daddy, whom the eponymous pooch falls in love with.

In the world of chase cartoons especially, domestic quiet invites a refutation, a disruption, a catalyst. Freleng indulges in a direct jump cut to said catalyst: a stealthy, cautious, and clearly seasoned in his operations cat. White lines expended with each blink immediately signify Dick Bickenbach as our inaugural animator.

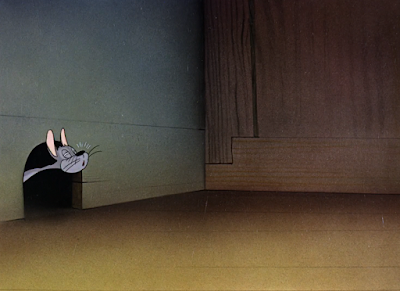

Intriguingly, rather than trucking in to the rather prominent mouse hole in the establishing layout or even a cross dissolve, the camera simply engages in a hard cut. This results in a rather abrupt jolt, even if there is nothing to detach the audience's attention from. Said jump isn't the result of directorial negligence, but, rather, a calculated attempt to farm unease and suspicion. Such a harsh transition indicates that something isn't exactly right. The cat appearing in such close proximity to the mouse hole cements the notion.

Slowly and scrupulously, the cat slinks out of his corner with a slice of cheese in tow. Even putting the similarities in design aside, it proves difficult not to think of how many mannerisms and beats from both the cat and Freleng's directing alike would later be imparted onto Sylvester.

It's all in the humanity of his movements--the cautious head turns, gingerly extending a leg out before creeping along. All anthropomorphized assets that we take for granted now, having decades and decades worth of cartoon's to compare to, but such decidedly human movements and thought processes were quite novel. No cartoon ten, maybe even five years before bore the same meticulousness regarding a cat pursuing a mouse. Having the cat interact directly with the background elements further cements the startling organicism of the acting and composition. An all encompassing dimensionality.

The same applies to the gesture of the cat testing for an ideal cheese placement. He spares repeated glances towards the mouse hole, the gears turning in his head as he gauges the distance exceptionally clear to the audience. All of these almost excessive acts of humanity are particularly in line with Maltese's sensibilities--the most menial human quirks become exceptional feats of attentiveness and consideration when imparted onto a cartoon animal. A sophistication that is almost inherently incongruous to the idea of a chase cartoon.

A somewhat arbitrary cut of the cat grinning from behind the wall follows. There isn't much of a reason for this scene to exist--it's barely even a few seconds long and feels a bit extraneous in the shot flow--but it is understood why it's there. Glimpsing at the cat with his proud, sly expression, an ironic "wah-wah" music score from Stalling to signify a playful nefariousness, the audience is all the more acquainted with what's at hand here. It's a confrontation of the cat's existence. There is a real predator-prey relationship occurring, a mouse is soon to be in danger and there is an identifiable culprit. Such a highlight, no matter how fleeting, is key in cementing so.

Conversely, rather than cutting directly to a tepid little mouse poking its head out of the hole, the camera instead follows the amplified scent of the cheese into the hole. Its smell pulsates in time to a score of "The Girlfriend of the Whirling Dervish", used to connote an exotic, tantalizing luxury. For a mouse, cheese isn't only a morsel to thrive on, but a pleasure. Pleasure that is knowingly manipulated by the cat. Prioritizing the cheese scent over the mouse in terms of introduction makes the audience more interested in who this cheese is appealing to--Freleng and Maltese play on a sense of mystery. Audiences are invited to be curious as to how the mouse will react.

"Just as planned" is the verdict.

Personification of the scent works on multiple levels. For one, the visual of a waft of cheese caressing a mouse inebriated in pleasure like a sultry lover is funny. It's an effective--if not ridiculous--manifestation of just how enticing the bait is to the mouse. Like the cat and his great care in tinkering around the cat hole and gauging the ideal distance of cheese, this caricature of simple cartoon clichés (mice like cheese) is a novel elevation of standard chase formula cornerstones. Again, think back to the cat and mouse cartoons from a decade before, where the setup was hardly more complex than "cat attacks mice eating cheese", both equally thoughtless in their motives.

Another point of success for the reveal of the Cheese Woman is that it plays off of previously established information. In following the scents wafting through the mouse hole, the waves pulsate in a rhythm. Rather than scoring the music to personify and accompany the action, the scent waves themselves almost seem sentient, mindfully bending and jerking to the movement. Thus, the oncoming anthropomorphization confirms any suspicions or observations of sentience.

If only tangentially, it should be noted that the same gag would be reused in Frank Tashlin's Nasty Quacks--same music, same motivation. Perhaps not the same obtuseness (as the "Eau du la Duck" does not take the entire shape of a sultry mistress, but only her hands), but molded in a very similar fashion. Freleng places a little more emphasis on spectacle and allure, Tashlin's interpretation is a bit more brusque to make way for the perfume hands being the same ones to warn Daffy of impending danger.

Unlike Daffy, the mouse comes to his senses on his own. Bickenbach's trademark elasticity works wonders in harnessing the rapid panic of the mouse--tall eye takes, loose, rubbery limbs, streaks of drybrush for additional frenzy that are thoughtful in their placement rather than random streaks of paint cluttering the drawings, and, of course, timing the drawings all on one's to sell the limberness of the motion. Double Chaser features a lot of this action, and not only limited to Bickenbach.

Even if the mouse is comparatively quick to break away from the spell of the cheese, he is perhaps even more hasty to return. Cautious sniffs--again indicated through Bickenbachian impact lines--morph into a juvenile, playfully sheepish smile, as if the mouse really is flirting with another figure off screen. Freleng and Maltese do a great job of committing to their motifs: the humanity of the cat, the obedience to his pleasures from the mouse. It's easy to forget that this airy mistress of dairy is, in actuality, just a slice of cheese festering on the ground.

Correction: just a slice of cheese festering in the grasp of the mouse. Extended comments regarding the organicism of the mouse's acting continues: his walk cycles as he retrieves the bait are varied--furtive tiptoeing that speeds up and back down, really conveying this lurching, cautious distribution of weight, a hasty sprint that fleetingly delves into a bit of a gallop, a running start with the cheese that eases off the acceleration back into the gallop-sprint.

In later years, Freleng would have had the mouse run to the cheese and back in one fell swoop, but the leisure time here in comparison is time well spent. Very observational and motivated movements. It's a great testament to Dick Bickenbach's penchant for motion and how it ebbs and flows in a way that is natural and second nature rather than obligatory.

Further praises for Freleng's direction include the surprise reveal of the cat waiting at the other end. Given that the short opens with his laborious attempts to trap the mouse, the visual of him waiting with his mouth wide open, mouse running directly into his metaphorical and physical trap shouldn't be much of a surprise. Still, the mouse's altercations with the cheese are quick to sucker the audience into the mouse's mindset and sympathy. Obtaining the cheese becomes the objective rather than worrying about how he's falling for a trap. Thus, the audience and mouse realizing the mouse's folly at the same exact time is yet another way for the audience to live vicariously through the mouse. Such establishes the mouse as the likable underdog and the cat, even in all of his charming, cheese distance gauging ways, as the ruthless enemy.

Even this early on, comparisons to The Cat's Tale are warranted. Freleng is able to establish double the information in double the time with none of the pedantry. Character designs of the cat and mouse are much more sleek, modern, considerate of motion; the angled, long heads on the cat and mouse help them "lean in" to the various running cycles that will soon ensue, contributing to a more effective and tangible speed and idea of a chase. The geometric spheres in the construction for Cat's Tale in comparison don't lend themselves to speed nearly as well. That, and the appeal factor for the designs of Chaser is so much more strong through less literal proportions.

Moreover, Chaser is silent (the only exception being a handful of sound effects, such as chicken noises or whistling). Cat's Tale is abundant with dialogue to a fault. So much time is spent with characters bantering--it's smart banter, as Tale is another Maltese effort that likewise dares to question the hierarchy of a chase, but the dialogue gets to feeling like a crutch after awhile. Or, at the very least, it certainly feels that way after seeing how clear and communicative the action is in Chaser with no dialogue. Barely a minute into the cartoon, and Freleng's improvements within a year are already exceedingly clear.

Chaser is much more simplified in its motivations: mouse accidentally gets eaten, realizes his mistake, runs out of cat's mouth, and the chase ensues. Bickenbach's frantic animation of the mouse whirling around in the depths of the cat's tail yet again perfectly encapsulates a very authentic panic and quick movement. Streaks of drybrush aid in selling the busyness of the motion, but are used to propel the movement (which is the base) rather than structuring the movement around a plethora of painted streaks. Timing the movement on one's again contributes to the limber alarm, and the tail itself follows a coherent arc to ensure that the movement does feel motivated and not like a string of different poses haphazardly slapped together. Wobbling aluminum effects from Treg Brown tie it all together with a trademark whimsy and surprising functionality.

And so, the ricocheting of cat and mouse alike takes our chase into the outside perimeter of the farmhouse, in which the remainder of are cartoon is contained to. Paul Julian's background work really deserves special praise all throughout, as they are much more confident not only in form, but light sources and just plain livability. Immersive, dynamic layouts--such as the low to the ground shot following the mouse as he rounds the corner--do wonders in allowing them to pop.

Freleng and his layout team get very creative and conscious with their scene composition, working background elements into the cartoon itself rather than offering a mere backdrop for cels to be slid across. Much of it is likewise out of necessity: the diminutive mouse needs broader, intimate staging to accommodate his size and even put the viewers in his shoes. The chase is much more vicarious by doing so.

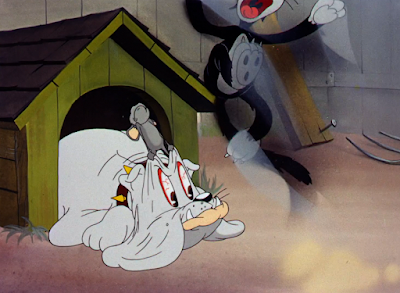

Enter the third equation to the chase. In Tale, the dog was introduced as being summoned out of the dark, cavernous depths of his dog house rather than sleeping. Tale's means of introduction establishes a foreboding mystery aspect, which is welcome--not being able to see the dog at all, who is named "Spike" and has literal warning signs placed outside of his dog house, fosters unease, and especially so when the cat is approaching him with the intent of confrontation. A lack of awareness for his demeanor outside of context clues is unsettling.

Here, however, showing him sleeping reaps its own risk. The mouse stumbling upon the dog means that the cat, too, will likely stumble upon the dog. This will wake the dog up, which is more provocative than summoning him out of his dog house already awake. A literal rude awakening does not bode well for the cat, or perhaps even the mouse. Stereotypical design cues of the bulldog--permanent scowl, spiked collar--inform the audience, cat and mouse alike that he is perhaps not the most amiable fellow on the farmyard.

As it so turns out, the dog is merely a scare tactic for the mouse to manipulate rather than an actual addition to the equation. He will become relevant later, as per the name of the cartoon, but for now, he remains asleep as the mouse pries the dog's exceedingly bloodshot eyes open to scare the cat. Cal Dalton provides the animation in this scene, noticeable particularly in the mushy mouth shapes of the cat as he's fleeing; his sense of timing is quick, attentive, sharp, the cat stopping only to do a surprised take before rushing away in a whirlwind of motion and even airbrushed smears. More urgency is packed in this scene than perhaps the entirety of Cat's Tale.

More smearing in the adjacent scene of the cat ricocheting back behind the house. Slowly but surely, the art of smearing and distortion has been perfected over the years, growing much more abstract as the animators discovered how best to caricature such a motion. Here, the cat almost appears to be a legless entity rocketing across the screen--sharp eyes will note that airy streaks of blue paint that stick out from beneath his body are to resemble his legs touching the ground. The resulting animation is an exhibition of pure speed and panic, which is very helpful in engaging the audience with the story.Of additional note is the layout; this same background has been reused three times, first to establish the mouse, then the cat, and now to disestablish the cat. Reusing familiar locations breeds continuity, which can even foster humor--to see the cat make his entry and exit so quickly in relation to each other with such synonymous execution is almost as amusing as the mouse weaponizing the dog and his horrendous, bloodshot eyes.

Nevertheless, the cat isn't entirely discouraged (and he certainly can't afford to be, given that the cartoon has just started). A knowing glance at the trash can adjacent to him seems to provide an answer to his troubles. Yet again, the background layout contributes a charitable amount of storytelling and dimension to the shot. Said trash can is beaten up, the lid askew and trash overflowing to make it look used, homely, believably inserted in its environments rather than a convenient prop.

Likewise, background elements are used to guide the audience's eyes through the scene: a wooden beam and its shadow attached to the wall forms a subtle frame around the cat, which fits snugly into the negative space from within. The eye is instinctually drawn to that area of the screen, preventing viewers from getting lost in any potential clutter.

Even to us, the extent of the cat's intentions are left to be purposefully enigmatic. It's only after a diagonal wipe back to the mouse and dog--the former lounging complacently atop the sleeping dog to bask in his momentary invincibility--that we discover the plan: more cheese, only fashioned this time to a piece of cheese.

Cal Dalton yet again animates the mouse in this close-up, occasionally varying the timing between one's and two's (the act of the mouse jumping off the cat or having the cheese ripped away is on one's, with slight distortions on his hands and body to accentuate the quickness) for a natural, spry feeling. The mouse's movements and even the movement in the cheese being thrown and yanked away feel organic and motivated rather than stock. Very bouncy, airy, snappy movement, again a far cry from the admitted stagnation of Cat's Tale.

Just as one can assume, the cheese lure is yanked away from the mouse in increments. As soon as he gets close to grasping it, the bait is lurched away, prompting the mouse to get closer and the cycle to repeat. Freleng has the camera lurching in time with the cheese to further imbue a real, physical tug. Directorial sympathy therefore lies with the mouse, as the filmmaking shares his perspective. Not only is the mouse pursuing the cheese, curious to where it's headed, taking that extra delay to register, but the audience is as well.

A shot of the cat pulling the string for clarity. More background elements (the trash can, the window) concoct a clever frame around him to guide the audience's eye and prevent them from getting lost in the detail.

This is a cartoon of subversion--after all, the entire story is reliant on transforming and questioning and complicating a standard chase dynamic. So, to effectively keep the audience on their toes, Freleng and Maltese have to distribute their surprises equally. The cat can't be the only one who has tricks up his sleeve. Nor can the mouse. Both must outsmart each other and, ideally, the audience in the process.

All of that is to say that the mouse turning the corner with the dog in tow is a brilliantly executed surprise. To go straight for the reveal requires, no matter how inconsequential, a directorial confidence of some kind; it's all too easy to bow to the impulse of showing the mouse glancing back at the dog, getting an idea, and then cutting to him dragging his unknowing security guard around the corner. Here, Freleng and Maltese trust the audience to read between the lines and resist the need for spoon-feeding. Deliberately showing the mouse and only the mouse as he peers out of the corner at the cheese is a great touch as well--every piece of evidence points to the mouse being vulnerable and alone until the last possible second.

More snappy timing and inventive distortions ensue. The art and technique of smearing is slowly progressing past simple elongation of a drawing, but harnessing multiples (which, as it sounds, is the repeating of a body part for a quick flicker of movement, such as the cat's three eyes or noses). These abstract multiples and smears juxtapose nicely against the more functional but equally as important distortions of proportions as the cat runs away. Again, the limberness and elasticity and sheer energy in the animation is to be commended, as it's a relatively new commodity. At least at this level of hyperactivity and speed.

So much so that Freleng even breaks out an entirely new technique: we see the cat beginning to round the corner, until suddenly his cel is nowhere to be on screen. One second he's preparing to run away. The next, he's absent. A cloud of smoke lifts off of the ground after a slight pause, allowing the audience to connect the dots and perceive that the cat has just left in a flash. Warner's would get a lot of mileage out of this motion shortcut--it's alarming, brash, confrontational, and best of all, economical. The artists were learning that an effective run cycle isn't about how many frames there are or their intricacy, but the manner in which they're used.

Returning to the complacent, cheese devouring mouse likewise heralds a return to Dick Bickenbach's animation. Ironically, the telltale eyeblink or impact lines--both of whom will come into play in a matter of seconds--aren't the immediate giveaway, but the particularly tall forehead on the dog.

What seems to be an artistic quirk is actually an accommodation; how else would the dog's eyes be able to elongate and travel up his face as he wakes up? Stretching his eyes like that before they even open gives the action of his opened eyes an extra push, a conscious effort to become conscious.

Cheese devouring mouse is regarded with apathy. So much so that the mouse doesn't even bother to turn his head to look at the dog, furthering his complacency and, in turn, the probable annoyance of the cat. Once more, the hierarchy is clearly established: the mouse knows he can rest on his laurels if he weaponizes the dog, both due to the cat's innate fear of the dog and the dog's apathy towards the mouse.

Cat's Tale hinged on a similar principle, but the mouse was much less involved. The mouse orders the cat to go bargain with the dog and ask for the dog to stop chasing the cat, so that the cat, in turn, can stop chasing the mouse--said dog doesn't listen to reason, cat gets beat up, and the mouse, resting away at home, also gets his desserts. There's a similar "barrier" here and alienation through the hierarchies, with both mice knowing the dynamic between cat and dog and how that will preoccupy the cat from eating the mouse, but the mouse and hierarchy as a whole feel much more involved in this cartoon.

Of course, disinterest on the dog's behalf turns out to be just as much of a detriment to the mouse as it is a positive. Yet again, Freleng and Maltese casually subvert the expectations of the audience--the dog leaving means that the mouse is unguarded, which, in term, means that the cat now has an opening to strike. A resulting shot of the cat creeping into the foreground, following the dynamic perspective of the layout and making him seem more like a tangible threat because he's getting closer to the screen, indicates that the cat does plan to take advantage of his good luck.

Further vulnerability of the mouse is instilled when it's made clear he doesn't recognize his current independence. Still soaking in his complacency, he sticks his tongue out and points at his security guard...

...only to find he's quit his post.

Again, further compliments towards Bickenbach's work are warranted. His work is almost comparable to John Carey's in that they're both excellent draftsman--with Bickenbach later becoming a layout artist for the Tom and Jerry cartoons to prove as such, the irony of working on this cartoon and later graduating onto T&J being duly noted--but also have an excellent understanding of motion. Bickenbach especially. The mouse's scared takes and scrambling efforts are loose and elastic, his "bones" broken (such as the floppy, curved limbs or long, tall eyes) to encapsulate clear arcs and a streamlined, unimpeded speed.

Just as well, Bickenbach is also able to capture comparatively more subtle means of acting, such as the mouse whistling for the dog and frantically looking under rocks, turning his head, etc. These movements don't require the same elasticity as a scramble take, but it's just as well--the comparative solidity and naturalism of the motion creates a solid antithesis to his scrambling and hysteria. He isn't all cartoony takes or all stolid acting. A mix of both makes for an organic panic with bursts of energy and human bits of acting that are motivated and observant.

Characters interacting with the background environments has been a consistent source of praise in this review. Characters turning heads around corners, interacting with walls--the backgrounds are environments that feasibly foster these characters rather than something to fill up the space on screen. Now, that background interaction adopts a more literal, objective view, with the mouse diving into an open hole (painted on a cel, implying said hole will be tampered with) in the ground. It's a different and more simple kind of interaction, more standard than the illusion of a character turning its head around a pointed corner, but using at all still works towards the end goal of making these characters utilize their surroundings.

Rather than having the cat look around cluelessly, unaware of the mouse's whereabouts or even taking the extra time to sniff him out, Freleng trims the fat by having the cat slide into frame and slam his paw over the hole in an unsuccessful capture. It's a good way to expedite a lot of fluff that chase cartoons can be prone to falling in--the inquisitivity and guessing game as to where the cutesy little mouse went. Our cat and mouse are a bit more springloaded for action, motivated by their natural instincts and not the instinct to perform for an audience.

Granted, the cat using a shovel to dig out the mouse isn't exactly a natural instinct, either. It is, however, a great piece of support that the cat is itching to find his prey and will do whatever he can to expedite the process. Using his claws and digging out the mouse like a dog finding its bone is primitive and humiliating. Shovels are streamlined, fast, snappy, and the cat using one falls in line with the observations of humanization seen at the top of the short. This entire bit of the cat digging out the whole yet again feels very Maltese-ian in its logic and compulsion to defy old stereotypes, so much so to the point of polite asininity. Using a shovel identifies the cat as a sophisticate. One who is above such childish games of dirtying his paws.

Animation of the shoveling is snappy, quick, supportive of the above arguments. The animators do get a bit "lazy" with the animation of the hole itself--after a certain point, the hole stops expanding, with the cat appearing to be throwing out an infinite amount of dirt. A way to avoid this is to have the cat dig down rather than out, as the circumference of the hole wouldn't need to be animated--just the cat digging deeper. However, for the purposes of this scene, reusing the same scene and shallow dirt length was the easiest option. Viewers scrutinizing the believability of a dug hole when watching the short in theaters is unlikely.

All throughout this sequence, Carl Stalling debuts a new track to his musical accompaniment: "Hey Doc!", most popularly heard through the 1941 Cab Calloway recording. It shouldn't come as a surprise to learn that Stalling would get a lot of mileage out of this song in the Bugs Bunny cartoons of the era. Like many songs adapted under Stalling's pen, this song has become a bit of a time capsule; if a short uses the song as accompaniment, it's very likely that the short was released in 1942 or 1943.

Instead of hoping to scoop up a shovelful of mouse on his way down, the cat prioritizes the carelessness of his dirt slinging and instead turns his attention to combing through the pile in hopes of finding the mouse writhing in there. Just like the cheese distance gauging, and just like the shovel using, this extra consideration makes him seem more human and, to us, amusing as a result. Likewise, Freleng is able to establish a satisfying directorial rhythm with the cat digging up one side of the screen and combing through the other. A very methodical divide of duties.

Establishing a rhythm is necessary for a number of reasons. One, and most simply: it feels good. The confidence in the routine from both the cat and director alike make for a much more engaging end result. However, the real priority is to establish a pattern that sucks the audience in--that way, the oncoming reversal is more surprising and damning, inflating the cat's surprise. What emerges from the dirt is not a mouse, but a pair of unmistakably canine ears that are attached to an unmistakably canine head, which, in turn, is affixed to an unmistakably canine body.

All that ever comes out of this gag is the silly non-sequitur: the dog doesn't bare its teeth at the cat or even seem to know what's going on. With a rubber, squeaky sound effect from Treg Brown, the cat forces the dog back into his pile of dirt...

...fashions the dirt around the dog's head...

...shovels the implied pile of dog...

...and dumps him back into the ground.

It's a great gag for a number of reasons. The most Malteseian reason is that it could be viewed as another commentary on the "convenience" of chase cartoons--an exaggeration of how the predator always seems to be looming around every corner, waiting to strike. Such an idea is taken very literally here. Likewise, the dog and cat seem to be unanimous in their confusion as to what's happened. The dog doesn't know why he's here, and the cat doesn't know why he's here; it's as if the creators that be (so, the cartoonists) dropped these two animalistic chess pieces into the same set and waited to see what would happen.

Animation of the dirt itself is a bit crude (at least in coming off of the very dirt-centric Gopher Goofy), but the motion is very smooth and swift. Timing of the animation is often on one's, during actions that require more concentration such as the cat digging out the hole, clawing the pile of dirt to cover the dog, or stomping the dirt back into the ground. An almost uncanny smoothness results due to the drawings spaced relatively close together. This isn't a bad thing, as the viewer can feel the acceleration of moment and urgency, and it certainly does make for a visually engaging end result--just fascinating. Like the loose limbed running takes, the motion here feels a bit experimental, even if the actions themselves are pretty self explanatory.

Maintaining the idea of inventiveness, Freleng's next scene transition is playful: after the cat successfully tamps the dirt back into the ground, he makes an exit. A slow cross dissolve lifts into the next scene, where the cat is standing in the exact same place where this dirt spot once was. Chuck Jones utilized the same "afterimage" technique rather prominently in Conrad the Sailor--there may not be as strong of an artistic or cinematic commentary here as there was in Conrad, whose set pieces were deliberately meant to impress with its sleek design, but the consideration behind the blending hook-ups reflects a directorial engagement on Freleng's behalf. It's evident he was thinking about how the shots flow together. He's present for this cartoon.

Gil Turner animates this next sequence that is easily recognizable to Freleng fans: the ever-beloved "Freleng Fence" makes a return. That is, characters tinker along one side of a fence, only for an opening in the fence to reveal that an adjoining party is doing the same in a mirror image. Borrowing the philosophies of the mirror gag in Duck Soup--a sequence that was rifely parodied in many a golden age cartoon--this general set-up can be found in numerous Freleng cartoons and seemed to be a pet gag of his. Notes to You was the first to debut it which, it should be noted, is another collaboration between Freleng and Maltese.

Staging of the gag in Chaser is a bit cleaner and more "objective" than the staging in Notes; the camera is pulled back further, and the sharpness of Paul Julian's backgrounds encourage a clear divide between what is the fence and what is not. Likewise, the cat moves in a side profile, whereas Porky operates in a gentle 3/4 view--the delivery feels much more streamlined in design with the usage in Chaser. Something that is rather amusing to note, given that Gil Turner's animation usually isn't praised for being streamlined. Likewise, the gag is about thrice as long and meticulous in Chaser than it is in Notes.

Mouth wrinkles on the cat as he turns his head forward and the idleness of his movement, seeming to bob and "breathe" when he's standing still, point to Turner's involvement. His sense of timing can err on the floaty and mushy side, as expounded upon in prior reviews. That nevertheless works to his favor here, in that the idle animation of the cat and the polite floatiness is a stark contrast to the motivation and purpose when he's slinking around the fence. Thus, his pausing seems more contemplative--he isn't supposed to be pausing, which means that something is up, and the differentiation in movement helps support that.

Something is indeed up.

Here is where the gag deviates from Notes. Both have the same general idea and same musical Mickey Mouse-ing, but Chaser's sequence is much more convoluted. In comes a mouse, out comes a dog, and then the cat himself. Confidence is yet again the name of the game--Freleng doesn't demonstrate or even make an attempt to explain why the dog is there, why there are two cats, and so on. To explain is to lose trust in the joke and to lose trust in the audience. Our only concession that yes, this is weird, are the bewildered stares and blinks and gulps from the cat towards the audience. Otherwise, the reveals are swift and unquestioning, just as they should be.

Freleng and Maltese even make this sequence propel the story. Rather than serving strictly as an amusing bit of visual business to occupy the audience, it keeps the pace going: after spotting the mouse yet again, the cat finally breaks the barrier in the staging and delves into the other side.

A brief pause, only to be interrupted through more elastic limb takes and frenzied running. Refusing to indicate what sent the cat in a tailspin until the last second is another strength of the sequence; the audience is more engaged when they're kept guessing.

Enter the dog. After all, he was on the other side of the fence. Maltese excelled at establishing a lack of logic that, in fact, does follow a basis of logic after all. The dog chasing after the cat is a surprise, too, but it can't be said that it was completely unexpected, given that the end result was just teased under our noses through the dog's presence.

The logical impulse is for the camera to cut into a high speed chase involving the cat and dog, background on a rotating loop as the animals chase each other--cat in front, dog behind--before cutting to a series of tangents. Instead, Freleng merely cross dissolves to an entirely different location, which is eery in its stillness and quietude. The transition is a bit jarring, as the audience almost expects to follow the whereabouts of the cat and dog. Likewise, the transition into the fence gag was a very synonymous cross dissolve; there's a little bit of double dipping in the cinematography, but not enough to the point of considerable monotony.

Reasons for why Freleng cut the scenes this way soon become clear. The short is entitled "DOUBLE Chaser"--the mouse is still a part of the formula. Thus, it is revealed that both cat and mouse have taken refuge in the shed, unaware of each other's company. More pantomiming in the vein of the fence sequence ensues; the head shakes, shrugs, and grins between cat and mouse are unanimous, methodically timed to be in sync and--for the first time--put predator and prey in the same footing. Stalling accentuates the actions with weepy, commentative violin slides that accompany the actions. By and by, as the cartoons progress, Stalling has found more ways to incorporate his music into a true commentary and accompaniment rather than just something to slap overtop the visuals.

Shared realization between cat and mouse is executed brilliantly. After having boasted such "togetherness" for so long, looking the same directions and smiling and shrugging the same way, their separation is conveyed literally. Mouse looks down, cat looks up. First subtly, then confrontationally so, with the mouse practically thrusting his entire body over the cat's face and fitting snugly into his silhouette. Then, when the inevitable surprised take ensues, they are propelled in opposing directions. Beautifully timed and arranged. Very clear cut in staging and presentation--again, something to praise after The Cat's Tale boasted so much of the opposite.

To expedite the process, the mouse seeks refuge directly beneath the mother hen. Timing of her confused, vacant head tilts and the slightly wobbly facial features yet again suggest the handiwork of Gil Turner.

Before getting too deep into this segment, Paul Julian's background work is due for some much needed praise. He's practically a starring character in the short itself with how tight, controlled, atmospheric and striking his backgrounds are. The last two are particularly impressive, given that "animals chase each other around a barnyard" isn't exactly something that would seem to yield such painterly backgrounds.

One of Julian's greatest strengths as an artist was his sense of lighting, and this particular painting demonstrates it well. Browns grow warmer and lighter in their hue as they get closer to the lightbulb, which itself is painted as a harsh white. No definition, no reflections, no shadows: just a blob of white that really communicates the blaze of the bulb. One can easily imagine reaching out, touching the light and getting burnt; Julian's backgrounds excelled at this naturalistic immersion. Likewise, the highlights reflected off of the elements in the corner (such as the table) really tie the environments together, indicating that they all feasibly occupy the same space.

Praises regarding the lighting are particularly warranted, given that the next beat in the story solely revolves around manipulating the light. In order to snuff out the mouse, the cat rifles through the hen's abandoned eggs, turns out the lightbulb, and holds each egg in front of the conveniently lit candle to gauge which egg the mouse is hiding in. Double exposure effects of the camera to get the glow of the candle are smooth and organized--it's difficult to remember that there was ever a time where these effects were so marred by after images and blurring and other miscellaneous errors in transparency.

Now, the idea of casting a chick in an egg in darkness, illuminated through a pinhole of light that requires some camera trickery to exist, doesn't even look as though anyone broke a sweat in figuring it out. The opposite was likely true, but the scene is remarkably free of hiccups and bumps. There are a few frames that are blurred, primarily involving the ones where the cat finds the mouse, but it's remarkably slight in comparison to what these scenes used to look like.

Due for equal praise yet again are the music stylings of Carl Stalling. Stalling and Freleng make a particularly dynamic team, as Freleng's proficiency in sharp, musical timing and Stalling's snappy, flexible music can make for some really compelling and rhythmic pieces of action. The cat shutting off the lightbulb is a great example of this; Stalling's musical accompaniment is a sneaky, moody music score that is accentuated by two beats on the end of the melody.

Shutting off the bulb belongs to the first beat. A laden pause as the cat turns his head... then, the second beat is assigned to the surprised take from the cat once he spots the chicken in the egg, the accompaniment finishing off the second melodic beat. It can only really be appreciated by listening and watching the motion itself, which is embedded below. Tugging on the lightbulb string and the surprised take have all the more oomph and power thanks to careful consideration of the music and timing.

Nevertheless, the cat's mission does indeed succeed, and he and the mouse share unanimously sly grins with differing intent: guiltiness out of the mouse, and deviousness out of the cat. Amusingly, in spite of all this, the cat finds it necessary to turn the light back on rather than immediately run off with his prize. Humanity is again a running theme with him.

Part of that is to divest focus into the dog, who has also come lumbering into the henhouse. Quick, aggressive head turns imply that he is looking for something. Bad news for the cat, but good news for us, as his walk cycle and head tilt turning is yet again brilliantly timed to the score of "Hey Doc!" in the background. His lumbering footsteps accentuate the beats of the movement, his head tilts timed as a secondary action to his walking. The level of organization and sheer confidence, the sheer sense of Freleng and company knowing what they're doing in this seemingly innocuous cartoon, is so refreshing and impressive.More Gil Turner animation as characterized through the cat's floaty head turns, sustained motions and affectionately mushy facial features. With the dog back in the picture, the power balance (or lack thereof) has been reset; now it's the cat who must hide and manipulate his surroundings rather than the mouse.

He does so by way of a red glove conveniently placed atop the table that wasn't there before. Highlights and shading line the glove, giving it a more solid appearance that attracts the viewer's eye and accentuates the asininity of the whole situation in making these props more tangible. It's easier to dismiss the cat putting a glove on his head and acting like a chicken as simple cartoon nonsense--which this is--but rendering the glove to seem more realistic, thereby grounding it and promoting a dissonance between this very realistic glove on the cat's head and the stupidity of his disguise.

Chicken noises ensue. Voice expert Keith Scott doesn't cite who was responsible for the chicken noises, and this is pure speculation on my part, but I would not be surprised to learn that it was Bob Clampett who provided them. The chicken sounds sound atypical from Blanc's usual impressions of a chicken, and Clampett was known to perform chicken voices in other cartoons. "It doesn't sound like Blanc to me" is the only argument I have for this, so I would not read into it too deeply, but it's at least worth throwing out there for the fun of it.

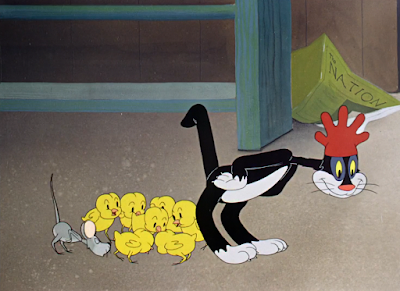

More deviation from typical cartoon clichés ensue. Most shorts would have the dog yank the glove off the cat's head, the cat grinning in humility and then running off before cutting to a chase. Here, however, Maltese and Freleng ride out the opposite and have the disguise be too effective: sitting atop the eggs prompts a plethora of baby chicks to explode out from beneath the cat. Treg Brown's hollow popping sounds are the perfect sound effect, emphasizing the whimsy and mischievousness of the entire scenario and likewise connoting how tiny and light the chicks are. Moreover, the cacophony of hollow pops illustrates to the audience just how many eggs have been hatched, and just how many chicks now likely think the cat to be their mother.

(It should be noted that the mouse is never shown hatching out of an egg.)

It is, however, implied, as he sneaks up on the audience and cat alike in the next scene. Still clinging to his obligations, the cat carries out his chicken noises, his adopted little ones happy to imprint upon him. This routine does stretch just a little bit long with lots of walking and clucking, but that is more a side effect of the ridiculous pacing this short has upheld thus far. Anything will seem belabored in comparison to all of the rubbery running takes and increasingly convoluted chase dynamics.

Moreover, much of the monotony is intended. Both the audience and cat alike are encouraged to get lost in the routine, fully committing themselves to the idea that this cat is now a chicken and will ride out this disguise for as long as necessary. The same is true of the mouse, who participates in the festivities for as long as he can until the cat notices. There is an intentional sense of routine and domesticity to be had in this highlight. That way, the inevitable realization that something is up--such as the cat finally recognizing the mouse pecking behind him--seems more damning and urgent through how much of a contrast it is in tone.

Perhaps the cartoon could best be summarized through the gif below. The cat grabbing the mouse and the chick, furiously analyzing the two, only to be grabbed by the dog who, in turn, has to reintroduce the oblivious mother hen back into the equation and untangle the hierarchies is the best indication of just how asinine and complicated this entire chase has become. Remember, this all started over a cat trying to lure the mouse out of his hole with a slice of cheese.

Animation of the resulting whirlwind is gorgeous not in its actual draftsmanship or motion, though the latter is particularly good, but what it represents. Multiples of the characters are seen running around on screen: at times, there are four different mice on the screen, or three different cats; the motion all occurs so quickly, with the characters running in so many opposing directions that the audience doesn't actually have time to dissect the reality of how many animals are on screen and why. Having these multiples nevertheless encourages the craziness of the entire charade, lessening the gaps in between characters and filling up the screen so that it is completely dominated by chaos.

So far, the cartoon has nestled into a bit of a pattern. A gag or sequence climaxes, only to cross dissolve or cut to a new scene that resets the playing field. There are multiple initiations of a chase, but never any actualizations of a real chase. Realizing that the cartoon is beginning to crest, Freleng and Maltese defy their own formula and indulge in a climaxing series of shots.

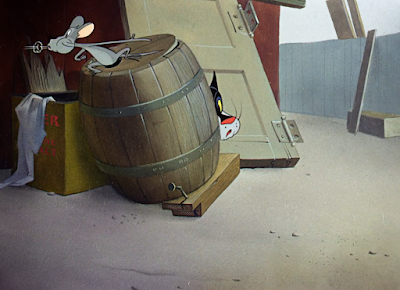

When the cat takes cover behind a barrel, the mouse weaponizes the dog's neutrality towards himself and attempts to become an active ally by calling the dog over through frantic whistling. This thereby inspires a sequence in which the cat seeks new hiding places, all of whom are thwarted through the tattletale mouse and the abiding dog. Fans of Freleng's cartoons will remember that Little Red Riding Rabbit--also written by Maltese--initiated the very same sequence with twice the ferocity and quickness.

Obviously, the pacing of the sequence here is much less hectic and choppy than Riding Rabbit, but that doesn't mean it's any less functional. Freleng enables more time for the audience to brood in the emotions of the characters (which makes sense, given that in the context of Rabbit, Bugs is pretending to be a third party and squealing on himself to the wolf, meaning there is no opportunities to focus on any panic or thinking), particularly the cat's. His elastic eye takes and contemplative head turns as he scopes out his surroundings inflate the gravity of the pursuit, as it's very clear he does not want to be found by the dog.

In spite of the cat's deviousness through the cartoon, the audience is encouraged to place some of their sympathy with him, since he too is prey of some kind. Nevertheless, given the fast, almost triumphant pacing and continued garnering of momentum, the cuts getting shorter and shorter as the camera transitions to new hiding locations, the primary objective is to both laugh at the mouse ratting on the cat and to get swept up in the adrenaline.

Our chase comes to an end when the mouse guides the dog towards some bushes. How do we know this is the end? Because the camera takes its time to rear back, following the dog as he enters into the scene, and then tracking his movements and chronicling his dive into the bushes. There's a poignant investment with the dog's whereabouts that the other cuts didn't have; especially the last few, which only consisted of the mouse whistling before transitioning on. Following the dog this closely means that there is a new development--or the closing of an old one--to be focused on.

Sure enough, the dog takes off into the bushes with a relatively rigid arc in his jump (or lack thereof). Rather than jumping in a curve, his body bending to follow an arc as he feasibly travels it up and down, his cel instead just seems to rise and fall in the motion of an arc, his torso remaining in the same splayed position. It's a minor note, as the bushes are soon to envelop him anyway and obscure much of the jump, but the rigidity does feel awkward when given just how loose and free the animation has been in the cartoon thus far.

Reminders of the convoluted chase hierarchies again come into effect when the dog lands head first in a pile of trash. Obviously, the mouse wasn't expecting this to be the case, but a face full of cuckoo clock makes it seem as if the mouse purposefully tricked him to fall into a junkpile. One gets the sense that the mouse's imagined sense of immunity has finally worn out.

A recurring trait of Paul Julian's backgrounds is to include references to his coworkers. Here, a box in the foreground is branded as "TOWSLEY BATH SALTS"--Towsley refers to Don Towsley, a longtime Disney animator who took up a short stint as Freleng's layout man in the early 1940's. Towlsey's initials can be found on a 1942 revised model sheet for Bugs Bunny which, unlike the 1941 and 1943 models drawn by Bob McKimson, are rather un-McKimsonlike. Bugs' appearance is much cuter, softer, less methodical than McKimson's drawings. Towsley, like Charlie Thorson and Bob Givens, is yet another in a fascinating string of ex-Disney artists drawing character layouts for Warner cartoons.

Nevertheless, our bullheaded bulldog is not thinking about the intricacies of who molded this cartoon. Rather, he's thinking about why he's landed in this junkpile and the cuckoo bird that has taken residence in his mouth.

Dick Bickenbach's animation is yet again identifiable through telltale eye blinks and, when the bird swarms in his mouth, the elastic, rapid, loose motion with smatterings of dryrbrush. Likewise, the dog's wide eyed expression when the bird--anthropomorphized and able to operate independently of the clock, which could almost be seen as another addition to this convoluted animal hierarchy--is consistent with Bickenbach's prior scenes of characters doing the same. This has been a very eye take and scramble take heavy cartoon.

A cut back to the cat and mouse reminds the viewer of from whence this convoluted insanity began. Whistles and points ensue, but Stalling's music score doesn't shift into the same dramatic tune upheld through the montage prior--surely, that is a signifier that the mouse's gestures are in vain. Not even the directing of the cartoon obeys to his defenses.

Nor the dog. So much so that he even engages in attempts to actively use the mouse’s methodology against him. In yet another subverted parallel, much like the dog appearing behind the fence or the chicks actually hatching beneath the cat, the dog whistles to recruit the cat to help him beat up on the mouse. Brilliant sound design in differentiating the sound of the dog whistling from the mouse’s—such makes it seem all the more unprecedented, different, a stronger breach of protocol. All important and effective, given that the mouse’s whistling was so rampant for so long. An entire montage was dedicated towards it.

So, for the first time in the cartoon, the viewer receives an objective lens of the chase. Panning background, cat dutifully in tow behind dog. This is the most obedient to a standard chase cartoon the short has been in its entire presentation. Noteworthy, given that the cat and dog are teaming up, which is a complete defiance of the genre as we know it.

Understanding that there isn’t much time to expand the chase further or add too much new information, Maltese and Freleng have the mouse retaliate by other means: painting an apple black, striking its stem with a match and convincing the dog and cat that it’s explosive.

It's an admittedly stupid gag, and both Maltese and Freleng know as such. That's what makes it so successful. To play it off as this serious, genuinely genius means of outsmarting the cat and mouse would be its downfall. The utter contrivance of the setup and the fact that it actually works, prompting some more animated eye candy as the dog and cat engage in some gorgeously smooth scramble takes, camera pan still going as they struggle to get a hold on the ground and slide in all different directions, scooping up handfuls of dirt... that is what makes this admittedly idiotic gag work so well.

Confidence from all ends. From Freleng's directing, posing this lit apple as a serious threat that the mouse takes pride in and the dog and take take panic in. From the mouse, posing it as this genius way to foil his pursuers. And, of course, from the cat and dog, whose panic at this explosive is very real. Nowhere is there any sort of concession that this is stupid, this is contrived, this is juvenile. There's a feeling of that beneath the surface, as it's not like Freleng is regarding this as the most brilliant gag ever conceived, but his directing doesn't demonstrate any cracks that discredit the setup.

In fact, it does quite the opposite: in yet another proud defiance of logic, just like the dog appearing from beneath the mound of dirt or the two cats mirrored across the fence, the apple explodes in a fiery burst. Freleng would grow to develop quite the penchant for perfectly timed explosions, and here is no exception; the apple only detonates after the mouse revels in his conceit, nodding and pointing at the apple just as he did the missing dog from before. That way, the end result doesn't seem so cruel. It only explodes once he volunteers to make an ass of himself.

"End result" being quite literal, as the next shot of our mouse friend is him ascending to his great reward. This, too, would become a common fixture of Freleng's cartoons--particularly those involving Sylvester. Here, there's a greater feeling of salt being rubbed in the wound, given that the mouse is holding the remains of an apple core, reaffirming to the audience that this was indeed just a physics defying apple and not an actual bomb slipped into his possession. Not only is the former option more fun, but more proud in its defiance of convention. Just like the entirety of this cartoon.

When analyzing the entirety of Friz Freleng's filmography (or the library of Warner cartoons as a whole), Double Chaser does seem to be just another footnote. A cartoon made to meet a quota and to help the artists hone their skills. Since there are no recognizable characters affixed to this cartoon, it must thusly be swept under the rug, maybe have its dust blown off through a recent restoration (which looks fantastic and does Paul Julian's backgrounds a great service) but largely forgotten. Many shorts of this era can say the same.

However, when analyzing Chaser from a strictly chronological standpoint, it really is quite a feat. It doesn't exactly reinvent the wheel--again, much of its existence seems to be owed to The Cat's Tale--but it does ensure that the wheel is functional and even spiffy. Freleng's sense of timing in this cartoon is quite possibly at its sharpest yet. If not the sharpest, then certainly in the running for the title. Characters are cheated to seem faster by having their cels disappear entirely from screen, characters poke their heads out of corners before the dust marking their exit has settled, there are overlapping exits and entries to bridge the gap and maintain a sense of momentum. All of these aspects are particularly crucial for a chase cartoon.

All of Freleng's animators are able to adapt and purvey the above notes, which is something that can't often be said. Usually, analyses of these shorts result in summations that are like "the animation is good, but Dick Bickenbach was really the only one able to capture a real tangibility in his motion--the others pale in comparison." While it remains true that Bickenbach's scenes have a very unique appeal that is difficult to trump, all of the animators involved were engaging in loose, rubbery takes and run cycles and frantic displays of motion. Cal Dalton got to experiment with some airbrushing, Gil Turner lends his hand to some wonderfully frantic run and surprised takes. A real synchronicity is felt all through the short, which is why it's as good as it is. Truly, Freleng is firing on all cylinders.

Mike Maltese's sense of humor really lends itself well to Freleng's directing. Maltese seemed to have an air of confidence in his gags and writing sensibilities--obviously, if he passes off an apple as a deadly explosive. Freleng at his best can be a very no nonsense, no frills director who prioritizes objectivity and boldness. Many of the laughs in his cartoon are achieved from presenting ridiculous gags, scenarios, or characters as objective fact. Maltese's confidence in his writing really lends itself well to this directorial confidence, and, when both are present and engaged, really play well off each other, as seen here.

If there are any criticisms to be had of this short, they are mostly in regards to other cartoons. "The whistle sequence isn't as fast as it is in Little Red Riding Rabbit" is an unfair criticism to give, given that there was no Little Red Riding Rabbit to compare to; perhaps Little Red Riding Rabbit wouldn't exist without this cartoon. Or, at the very least, differ foundationally in some way. "Freleng uses two cross dissolves in a row" or "this purposefully monotonous chicken bit feels monotonous" are in a similar boat. Worth pointing out, but extremely nitpicky and have no broad effect on the quality of the cartoon.

Even if this cartoon has been eclipsed by many other chase cartoons, both from this studio and others, it is still a fantastic little footnote for its time period. The motion, the gags, even the character designs feel uniquely Looney (capital L and extraneous e); one would be hard pressed to view this cartoon and not think about how it feels like such a precursor to the wild, brash, inventive, genre-defying cartoons that would be churned out by both the Freleng unit and the remainder of the studio. Double Chaser is an exceedingly promising sign of what's to come: even if that's just another "dog chasing cat" cartoon.

.gif)