Release Date: July 15th, 1939

Series: Looney Tunes

Director: Bob Clampett

Story: Bob Clampett

Animation: Bobe Cannon, Vive Risto

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Porky), Shirley Reed (Petunia), Berneice Hansell (Pinky)

(A link to the cartoon may be viewed here!)

Counting Bosko, the Talk-Ink Kid, Porky's Picnic marks review #250: 1/4 of the WB catalogue has now been dissected. In that time, my analyses have gotten much more thorough and passionate. This venture began as an excuse to motivate myself to watch all 1,000 original cartoons--it has now evolved into a passion project, with the background information and knowledge aiding my work as a cartoonist working in the animation industry. Likewise, my experience as a professional cartoonist has helped to provide further insight into how these shorts were made. Whether this is your first review you've read yet or you've been with us since this venture started in December 2019, I wanted to say a quick thank you for all of the support and insight from readers and friends. I'm very excited to see how this journey progresses, and I do hope you'll stick alongside us the entire way through.

Porky's Picnic is a fine cartoon to mark the occasion; Petunia Pig is brought out of retirement for a brief stint under the direction of Bob Clampett, and Porky's nephew Pinky bows out of his own animated tenure. A perfect encapsulation of Clampett's "adorable masochism" mentality, the seemingly innocuous short about Porky taking Petunia on a date to the park is rife with hyperactive, overzealous energy, innovative environments, and an abundance of slapstick.

As opposed to opening with a series of pans, idyllic backgrounds and gentle music furthering a sense of calm sure to be refuted by whatever wacky antics lie in store, Clampett instead jumps straight to the goods: Porky is promptly introduced as he putters through town on an electric scooter. Armed by an innocent and jolly backing track of “Sticks and Stones”, Bobe Cannon’s gentle animation of Porky and his bike swaying at contrasting angles is constructed, smooth, and successfully hypnotic.

Common to the early Clampett’s pig is a greeting towards the audience, with Porky in Wackyland and Chicken Jitters both adequate examples of his establishing a sympathetic relationship to the viewers through direct acknowledgement of their presence. With his hands full, a silent, open mouthed nod suffices in lieu of a wave.

As Porky struggles to pronounce Petunia’s name (“I’m going to see my eh-guh-geh-eh-girlfriend, eh-puh-eh-puh-peh-peh-peh-peh-peh-peh-ehh-puh-puh-puh-puh-ehh-puh-puh-puh-eh-puh-puh-puh-eh-puh-eh-puh-puh-puh-eh-puh-puh-puh-puh-puh-puh-puh-puh-puh-puh-puh..."), a somewhat arbitrary jump cut is made as the camera trucks in at the slightest interval. The difference between the two shots is slight at best, and the intention confusing other than an attempt to reduce monotony, though it would seem the dialogue and animation would do a serviceable job tackling the latter point.

Nevertheless, Porky’s profuse stuttering is a much higher priority than awkward camera cuts. After struggling for six seconds straight, he merely chuckles it off, a stark contrast to the frustration exuded by Jones’ Porky in Old Glory. In yet another rare admission of his impediment, Porky merely chuckles “Heh! I sound like a muh-meh-motorboat.”

After introducing Petunia through name, Bobe Cannon slips in possibly one of the funniest facial expressions ever to grace Porky’s face. Completely wordless, no acknowledgement of it before or after, highlighted through Stalling’s brief string solo in the music, he scrunches up his face, rocking his head back and forth as he hoists his fists up as if to say “Look at me go”.

It’s such a joyously needless gesture, but especially funny from such a typically conservative character such as Porky. The execution feels so natural—no awkward beat or halt as the audience is encouraged to soak in that Porky made a funny face—that it ties into the philosophy that a majority of Porky’s humor stems from his own mannerisms. Though he may not often come up with witty retorts or doesn’t usually serve as a vessel for screwball comedy, much of his charm and humor are derived from bursts of personality rooted purely in their earnest. Amusing and odd as the gesture may be, the audience knows it is rooted in sincerity, which is where the comedy stems from most.

A glimpse at the buildings in the background when Porky enters town reveals a number of hidden gags. Namely, storyman Ernest Gee is granted a name drop on a storefront, whereas a rodeo is advertised on another. Likewise, when Porky approaches Petunia’s house, it appears a billboard on the corner makes a reference to the Ray Katz Studio in which Clampett and his unit were operating out of.

On the topic of approaching Petunia, Clampett strives to sustain the jauntiness felt in Porky’s introduction. A character in Bob Clampett’s world simply can’t pull into a driveway, park a bike, and walk along the sidewalk. Instead, Porky skids through a series of sharp turns and dismounts his bike with a front flip. A contrast to his more demure personality? Sure. Needlessly elaborate? Certainly. However, the delivery is musical, joyful, and succeeds in its mission to ease monotony through seemingly mundane tasks. Setting the scene in a single down shot further introduces unconventional staging that is visually engaging, as well as a smooth means of connecting the routine together. A shot for Porky making a turn, another shot for him rounding yet another curb, cutting to a new shot to show him pulling into the driveway, etc. would be tedious and leech the desired energy.

Continuing to grow more concentrated as Clampett’s filmography stretches on, Porky’s signature double bounce walk is given its own spotlight as he tinkers up to Petunia’s doorway. Its musicality once again pads the action and saves it from being too awkward, with every footstep marked by the strike of a xylophone and the bounces serving as a physical manifestation of the music’s own pep. While the walk may be relatively new to Porky himself, its philosophy is one of the oldest tricks in the book, subscribing to the structure of the earliest sound cartoons where every single movement was a musical instrument in itself.

Bobe Cannon continues to provide animation for Porky’s arrival, immediately noticeable in the tapered mouth shaped and occasional dimples. It certainly seems Clampett trusted him as an animator; many dialogue scenes or meticulous bits of action—as is the case here, where Porky hesitates on ringing the doorbell to pause and make himself presentable—were entrusted in his care.

The sequence at hand certainly makes a good case for Cannon’s abilities. Yet another scene which could be potentially laborious in lesser hands is made endearing, charismatic, and—of course—amusing as Porky knowingly fixes himself up in front of the audience. A few tugs at the bow tie coupled with a relatively cheeky but innocent grin at the audience is earnest and entertaining enough, tugs and sweeps of his jacket seemingly small but welcome and keen indicators of Porky’s often meticulous personality, but the true crux is saved for last as he nonchalantly unearths a comb from his pocket.

As evidenced by Porky’s Party (where Porky’s dog gets drunk off of his hair tonic), Clampett harbored a love of poking fun at the pig’s hair loss. Cannon’s relatively intricate combing animation certainly strengthens the sequence beyond a standard bald joke. Rather, Porky goes so far as to part his hairline, grabbing and sweeping an invisible strand of hair to the side as he works with the comb.

Like so many shorts have taught us before, the success of the gag is owed largely to its innocuousness. A lack of acknowledgement of its implausibility renders it as just another one of Porky's routines; he is viewed as endearing, if not eccentric, rather than trying to show off or be funny to the audience.

Environmental oddities and sustained mischief are maintained as a simple ring of the doorbell instead prompts a mechanical hand to knock on the door. Yet again unsurprised by the twist, Porky uses the knocking as another opportunity to give one last adjustment of his bow-tie. His meticulousness is engaging, sincere.

Knocks in tandem to "Shave and a Haircut" delegate the final two-note punchline to the top of Porky's hollow head. His surprise is only temporary, again subscribing to the early Clampett philosophy that blows to Porky's head are funny only if he is relatively unscathed.

Enter Petunia, whose prior teases of cameos in Polar Pals and Scalp Trouble have finally manifested a physical return. One wonders if her appearance was mandated by Leon Schlesinger or perhaps the decision of Clampett himself--an appearance in the storyboards for Porky's Party possibly suggests the latter, whereas the briefness of her tenure and heavy lack of inspiration in her next and final animated appearance, Naughty Neighbors, suggests the former. She continued to be a relatively prominent piece of marketing, making countless appearances in the Dell comics run starting in 1941, but was seldom heard from or demanded on the cartoon front.

Rather than the sultry, if not at times demanding persona of Frank Tashlin's Petunia from his 1937 efforts, Clampett's Petunia is much more cute, innocent, and bubbly. Even her greeting of "Why, Porky!" is a stark contrast to the disdainful greeting of Tashlin's Petunia in Porky's Romance ("Porky Pig--pooh pooh!")

A "Eh-guh-gee-eh-gee-eh-guh-gee-eh-good morning, Petunia!" from Porky segues into a rather arbitrary close-up shot. John Carey's animation is certainly a welcome shift, solid as ever, but not enough to constitute a shift in scenery, especially for only one line of dialogue ("Would you like t' go to the pic and have a peh-eh-parknic--I-I mean the park, and have a-a peh-pih-picnic?") It may have been a consequence of Clampett casting animators, feeling Carey was the best fit to show Porky briefly fighting with his words, but it would make more sense for the shift to occur when Petunia first opens the door, with the camera already cutting closer on the two of them. A cut back to the first animator as Porky is still talking makes the shift seem all the more shoehorned.

"Would I?"

Petunia's split second retrieval of a picnic basket takes a page out of Tex Avery's philosophy of a character present, leaving, then entering in seconds flat, but is delivered through a Clampettian lens with its promptness and zeal. Petunia firmly establishes herself as a member of a Bob Clampett cartoon, where every little motion must be as whimsical and energetic and playful as humanly possible. She, too, shares the youth and pep of Clampett's Porky.

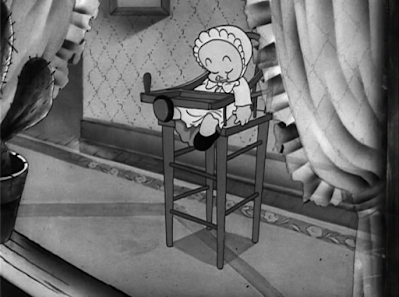

A lack of a writing credit possibly indicates Clampett storyboarded the cartoon himself, which is evident through a smattering of particularly creative and dynamic bits of staging all through the cartoon. Exhibit A is presented through a split-screen effect with skillful awareness of both positive and negative space; a window divides the scene in two, with Porky and Petunia's heads bobbing along the bottom, and Pinky (making his return from Porky's Naughty Nephew, now evidently a relative of Petunia's) sleeping in his chair through the window at the top.

"Sleeping" is to be used loosely when discussing Pinky. Carl Stalling's demure accompaniment of "Good for Nothin' but Love" grows brazen and touts a swing in its step as Pinky not so innocently cracks an eye open, ensuring the coast is clear. Like the remainder of Clampett's characters, Pinky has grown more streamlined in design compared to his appearance in Porky's Naughty Nephew, now less pudgy and less sickeningly adorable, voice unpitched.

Norm McCabe appears to be the perpetrator behind the wonderfully elastic bit of motion as Pinky pops an eye open, his design sense growing more noticeable in the thin snout and double eyebrows. Yet again, Clampett's staging is comparatively inspired, curtains and a cactus framing the scene and directing the viewer's eye to Pinky as the audience is given a view through the window. Staging following perspective and running at a slight diagonal angle gives it more depth and reduces any static posing or framing; a particularly welcome detail is that the curtains are slightly transparent, Pinky still visible beyond the painted overlay when he turns his head to double check his company is absent.

Clampett continues to assert that this is a short with his name on it, evidenced not only through the energy and eccentricity of the characters, but their environments as well. Everything in a Clampett short is fair game. Therefore, it is only logical that Pinky pull a lever on his highchair, prompting it to retract to the ground and give him free reign to escape. He could have just climbed out of the chair and scaled down to the floor, but in a short that has established itself with backflips for bike dismounts and robotic doorbells-turned-knockers, a lever activated, retractable highchair is the only sensible solution.

With that, we cross dissolve to more domestic matters as Porky and Petunia jovially bob along their merry way in Porky's bike. A musical reprise of "Sticks and Stones" parallels the cartoon's opening, Petunia's addition reflected in the concentrated harmonies and excitement present in Stalling's orchestrations. Staccato notes further represent the bounciness in both the bike and the duo occupying it, easing any visual monotony through a looping pan with the aid of infectiously happy music.

Unlike the opening, however, their joyride is interrupted by the offscreen honk of a car. Admittedly, the motion of Porky pulling into the foreground is undesirably janky, the strife to maintain bouncy energy making for some unintentionally jerky movements, but is nevertheless in line with the prevailing hyperactivity of the cartoon thus far. It further provides a convenient excuse for Petunia's hat to be discarded and remain hat free for the remainder of the cartoon as it falls into the sidecar.

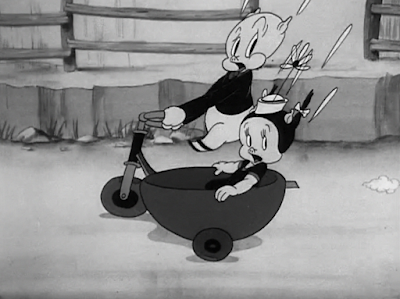

Who else is to enter in the background but Pinky, brandishing a scooter of his own as he passes Porky and Petunia.

A handheld horn is revealed to be the source of the honking. Yet again, having Pinky physically carry a horn, revealing it after a handful of seconds where it is hidden creates a less expected and thusly more rewarding payoff rather than showing the horn built in on the scooter. Hardly two minutes in, and surprises are already plentiful.

A transition between Petunia remarking on Pinky’s presence to Porky speeding up and catching Pinky in his arms after he trips over a rock is swift and clear. The pause between two scenes is timed just right—short enough to keep the momentum steady, long enough to allot a reasonable amount of time for Porky and Petunia to get back into position and catch up. Likewise, Pinky’s spill over the rock is emphasized through music rather than dramatics; a cymbal crash is marked with both the impact with the rock and when he lands in Porky’s grip. Props to Clampett and company for making Pinky’s addition to the party prompt yet concise.

Intriguing staging resumes with a shot animated by Bobe Cannon, the tight camera angle placing heavy focus on Pinky. Porky is cheated through the upper left corner, face visible as he addresses Pinky. With his butt still planted on the seat of the bike, the angle in which Porky is twisted is realistically almost impossible, but is functional, which is—and should be—the priority.

Cannon does a wonderful job of appealing to the audience’s sympathetic side with his animation of Pinky. While Porky promises him a story (leading to one of my personal favorite bait-n-switch stuttering examples: “Nuh-nee-neh-now Pinky, if you be a guh-gih-gih-eh-good boy, I’ll tell ya the story of the three eh-bih-bears and eh-guh-gih-gih-Goldiluh-eh-luh-leh-luh-eh-Goldil-uh-leh-leh-leh-leh-ehh—a little peroxide blonde,”), Pinky innocently rocks back and fourth, sporting a pouty face as he attempts to feign sympathy for being caught. Likewise, his perking up at the prospect of a story is gradual yet poignant, obedient nods displaying just how good he can be.

However, the audience is quick to discover that Pinky’s jubilation isn’t necessarily a result of being promised a story, but a distraction. Cannon’s animation of Pinky turning his head, directing his attention to the bolt connecting the bike and sidecar, is gorgeously smooth, the baby bonnet almost distracting and extraneous in the gentle, grandiose arc it follows, lace trailing behind in a gentle follow through.

With Porky prattling on in the background, Pinky uses this as a ripe opportunity to grab the bolt free from the bike and sidecar. His not-so-innocent grin as he holds his new prize speaks volumes. It’s almost as though he’s poking fun at not only Porky, but the audience as well for falling for the cute and innocent act.

Pacing continues to be swift and seamless as the separation between Porky and Pinky/Petunia is executed in a wide shot, a fork in the road conveniently furthering Pinky’s deed. Various signs, houses, and splatters of flora in both the foreground and background sustain visual interest and depth in the layouts.

Rather than prompting a wild take from Porky upon realization that he’s been deserted from his date and scrambling on a wild goose chase to save the baby and be the hero, he instead prattles on with his story, completely oblivious to the situation. That again makes him appear as a more endearing character—there are no attempts to paint him as a courageous hero ready to save an infant from harm’s way and impress his girl. Instead, he’s blissfully unaware and showing no signs of pausing his story, which is admittedly more interesting and amusing than the alternative. As a result, Pinky’s venture is made seemingly more dangerous with nobody to stop them, and, for the moment, droll hero type clichés are avoided.

A shift from John Carey’s animation of Porky to a less solid animator handling Pinky and Petunia is noticeable in a change in draftsmanship. Weaving in and out of the foreground in the uncontrollable sidecar, the animation is based purely on energy and feeling rather than solidity and construction. That in itself is fine, though Pinky and Petunia do feel particularly choppy in their movements, motion reading as frenetic and aimless flailing rather than conveying simultaneous joy and panic.

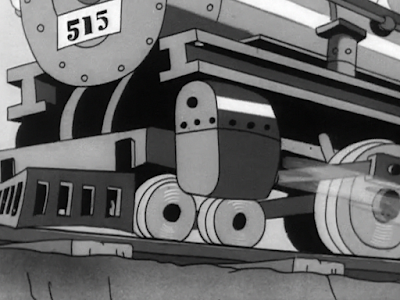

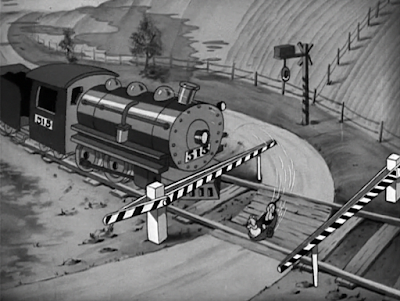

Trained eyes will recognize the shot of a train approaching from 1934’s Rhythm in the Bow, armed with Carl Stalling’s climactic yet spirited medley of both “William Tell Overture” and “Concert in the Park”, both conflicting tunes blending together particularly well and smoothly at that. While Stalling is an undisputed master of his craft, his ability to mesh two conflicting song numbers together, especially of conflicting genres and time periods, is a particularly impressive feat that could stand to garner more recognition.

Regardless of how awkward some of the animation may be of Pinky and Petunia awkwardly flailing about, Clampett does a relatively solid job combining reused animation with new. Moving backgrounds and props shown as Pinky and Petunia approach the train from behind borrow the techniques of cartoons from yesteryear, typically reserved to indicate a climactic chase, yet are refined through the knowledge and advancements of the then current animation stylings. That is, the style of backgrounds animated in perspective calls back to a previous time, but is delivered through the refined execution of a 1939 cartoon.

Clampett borrows a page out of Tashlin’s book regarding the cinematography. A series of somewhat fast cuts are made, with close-ups (a tight shot of Pinky and Petunia in the sidecar, a shot of the train’s wheels) and dynamic camera angles (an up-shot of Petunia covering her eyes while Pinky giggles) aiding the endeavor for dramatics. Cutting could aim to be quicker, with the addition of double exposed overlays perhaps rendering the montage as more Tashlinesque and thusly more urgent, but it certainly does convey the gut feeling of impending doom. Carl Stalling’s music score teetering on the joyful side rather than panicked makes it all seem like a happy game, which works for Clampett’s style established in this short.

The montage literally screeches to a halt when both Pinky and Petunia and the train intersect; rather than having Pinky/Petunia be stopped by the gate to let the train through, the train itself is stopped to let its company pass as the gate defies logical physics and turns to block the train off. More props to Clampett—having the gates change at the last minute rather than showing them in the position to stop the train to begin with maintains the ever recurring surprise element so cherished by this cartoon. A sharp eye can spot the gates turning on their axes in order to block off the train, though the barriers themselves close too quickly for a theatrical audience to point out the change. Function over logic.

Knowing the excitement of the chase can’t possibly be topped with any more of extraneous antics by Pinky in the moment, thus serves as the perfect opportunity for Porky and his lost company to reconnect. A wide shot paralleling the beginning of the sequence where they split in the first place, the merging of the fork in the road, the click of the bike and sidecar uniting together, the continuous camera pan, and finality in Stalling’s accompaniment of “Concert in the Park” all make for a satisfying, swift unity. Foreground and background details continue to neatly frame the action and provide visual depth—Clampett makes a shoutout to the very cartoons he works on through a billboard: “LOONEY TUNES — A SITE FOR SORE EYES”.

John Carey now animates Pinky and Petunia in addition to Porky as the story of Goldilocks and the Three beh-beh-beh-Bears comes to a close. Porky’s complete oblivion is, in its own way, just as fun as the wild train chase, implying he just told an entire fairytale to himself and didn’t bother to question a lack of responses. Likewise, one can just barely make out Porky’s mouth moving in the wide shot as he rejoins his company, indicating that he’s still rambling on with his story.

Bobe Cannon also continues to perfectly encapsulate Pinky’s faux innocence, propped up against the side of the sidecar with feigned interest. Revisiting same scene compositions seen at the beginning of the sequence—the aerial shots as they leave and rejoin, the rolling horizontal pan as Porky rambles on, the close up shots of Pinky in the sidecar—give it a neat and concise bookend.

Pinky is receptive to Porky’s story, words truthful as he giggles “Gee! That’s the best story I never heard!”

A cross dissolve between Pinky and the gang entering the city park lingers; the slow fade provides ample time for the audience to gaze at yet another coy, innocent pose from Pinky. The filmmaking is very sincere, though the dissolve strikes an effective balance between earnest and sardonic humor. A transition between plucky to jazzy musical accompaniment furthers the bridge and indicates new antics are soon upon us.

Dick Thomas was an unsung hero of the early Clampett cartoons in terms of background work. Later moving to Frank Tashlin and Bob McKimson’s unit in the ‘40s, his style of painting was typically literal, but, under the right direction, full of enough artistic flourishes to make it engaging and functional. Texture was often a major component of his style, which is beautifully displayed through an aerial layout of the shot, the dotted, blotting texture of the trees harmonizing nicely with the smooth strokes of the grass and roads. Thomas was great at painting values and contrast in the black and white Clampett entries—foreground elements such as the gate to the entrance or shrubbery at the bottom corner of the pan both deepen the composition and embolden it, dark and light hues working off of each other to be bold and helpful as a visual guide.

As we have seen thus far, a cartoon about Porky going on a picnic seems outdated and boring just through the title alone. It sounds like the plot of a 1932 Mickey Mouse cartoon, not a 1939 Porky Pig cartoon by the same guy who made such wild entries like Porky in Wackyland or Porky & Daffy. Knowing this, Clampett repeatedly attempts to stress the unconventionality of this cartoon’s setting through an over abundance of needless energy for the most menial actions, as well as packing plenty of surprise twists and eccentricities as a whole.

Yet another one of the cartoon’s many eccentricities arrives when Porky and company make a stop; instead of a single character saying “Here we are!”, all three characters feed their lines to create a sentence. That is, Petunia starts with “Well…”, Porky provides a “…uh-here…”, and Pinky finishes with “…we are!” Admittedly, the decision feels more disjointed than it does creative, likely due to the pauses between each character before they speak. It at least doesn’t appear out of place for the format of this particular short, feeding into the prevailing whimsy.

In any case, Porky, being the attentive, considerate, exciting date that he is, declares he’s going to take a nap. Similar to Petunia’s own start and stop exit of rushing to get her picnic basket in seconds flat, Porky’s announcement is split in two. His “Eh-guh-gee-ehh-guess I’ll take a nuh-nee-eh…” is interrupted as he scrambles from his bike and darts into a nearby hammock, finishing his “…nap,” once in the security of said hammock. Clampett would reprise the structure of the gag similarly in Porky’s Hotel, shedding some insight on what jokes he thought was funny or effective at the time.

A cut back to Pinky indicates comparatively more exciting antics are on the horizon. Though “cute characters doing or being subjected to sadistic acts” has been a well established Clampett trope for the past year or so, it is particularly concentrated in Porky’s Picnic, largely speaking for the short’s success. The audience is lured into a false sense of security through the saccharinity of a squirrel galloping and feasting on a nearby walnut as Pinky gleefully observes. Its design is cute, its movements somewhat graceful for early Clampett standards, brief pauses and halts as it moves conveying sentience (rather than just a mindlessly happy squirrel gliding into the scene.)

With that in mind, the only logical solution to approach the squirrel is having Pinky come up from behind with a convenient pair of scissors in tow.

To try and snip off its tail is one thing. To deliberately approach it and attempt to cut off the squirrel’s head, with the scissors snipping together and the squirrel saved only by reaching after its fallen walnut, is another. Pinky isn’t attempting to intimidate the squirrel—he absolutely has plans of cutting off the squirrel’s head and doesn’t see anything wrong with it. Attempts to mimic the Disneyesque philosophy of cute animal antics are deliberately tarnished through the Clampett school of thought in pure, unadulterated sadism. This scene here directly disproves any claims that his early cartoons weren’t pushing the envelope or bold in their own way—while he would continue to stretch the boundaries and garner the crew able to execute his vision unhindered, his earlier cartoons are very bold and wild in their own right.

Barbarity continues as Pinky now chases after the squirrel, cruelty on the rise as the scissor snips grow more concentrated as the squirrel grows more panicked. Like the train sequence, Clampett paints the scene as more lighthearted escapades through a jovial music score from Stalling rather than one that is panicked or dramatic. In a way, the childishness of the music makes it seem even more gruesome than the alternative.

Norm McCabe’s perspective animation of Pinky weaving in and out of the background pursuing the squirrel is solid, the skidding motion of the squirrel particularly grounded in weight but not hindered by it. Both characters slide and flow across the screen with necessary, purposeful energy, the gliding motions purposeful and not a symptom of misguided animation.Moreover, Clampett is again able to pull from his environments and transform them. A tree stump with three knotholes is turned into a vehicle for the world’s most barbaric game of whack-a-mole, Pinky looming over the top and scissors snipping together each time the squirrel pokes its head out and back inside. Stalling’s violin slide accompaniment as Pinky moves to attack and alarmed chords whenever the scissors click together perfectly caricature the motion through music. 5 attempts to attack (with a sixth interrupted by Petunia, who drags him away and scolds him) are satisfying—not too long, not too short. Comedy often comes in threes or fives, depending on the demands of the scene, and works here to establish a pattern but not one that’s monotonous.

The next sequence of Petunia putting Pinky down for a nap next to Porky serves as a direct parallel to Porky’s Naughty Nephew. Pinky’s altercation with Porky here is abridged compared to the former example, but also blatantly more violent. Where Pinky plays in the sand in Nephew, using a plastic shovel as a means to smack Porky in the face, the Pinky in Picnic upgrades to more blunt materials: a large plank of wood conveniently available near Porky’s hammock.

Comparisons to the original sequence in Nephew also bring about refinements, which are welcomed. John Carey is yet again succinctly cast for the sequence—his drawing style is appealing and cute enough to be innocuous, serviceable, but his energy and keenness for snappy, elastic motion is wholeheartedly welcomed. As he did in Nephew, Pinky does a double take upon the realization that Porky is asleep, able to literally abuse the circumstances for his own bidding. However, Carey’s double take is twice as energetic as Bobe Cannon’s own in Nephew, which prioritizes solidity and realistic character acting. There is no right or wrong approach; Cannon’s acting is gorgeous and convincing, working well with the demands of the former cartoon. Carey’s smears and air brushed distortions here contribute to the prevailing hyperactivity of the cartoon—even a simple turn of the head must be overzealous.

Both sequences ensure a stealth walk from Pinky, tinkering around Porky so as not to wake him up. Likewise, Carl Stalling’s musical accompaniment reflects the footsteps through light string plucks in both cartoons. The accompaniment here of “Deep in a Dream” is comparatively more domestic and saccharine than Stalling’s score of “The Japanese Sandman” in Nephew, making for a heavier, emboldened contrast when the inevitable walloping strikes.

A momentary pause before Pinky strikes is present in both scenes, though the suspense has been tweaked to be more potent in Picnic, reflected through a climactic musical crescendo. Furthermore, slight smears, grandiose visual effects upon the impact of the wood with Porky’s face, and Treg Brown’s heavy, echoing “SMACK!” sound effect all contribute to make Pinky’s masochism much more pungent and advanced than his feats in Nephew. Whereas using a sand shovel as a weapon is more of a side effect of playing in the sand, a “might as well while I’m here” as the prevailing attitude, deliberately using a wooden plank as a bludgeon feels much more targeted and less accidental. Consequently, his abuse feels much more violent. The blank grin on Pinky and innocence as he zips back to his spot are crucial to maintaining humor over pain.

As was the case in Nephew, Porky wakes up with a series of wild, spinning head takes. Carey’s distortions are stretched to further lengths than Cannon’s, to the point that even the inking and painting reflects the sensation of the movement. For a few brief frames, Porky’s face is colored pure white, the outlines a light gray rather than black in an attempt to indicate simulated motion trails, the audience filling in the missing blanks. The distortions are pure energy and feeling. The blanching of the colors for those single frames makes the movement feel more frenetic than it actually is. A shift to a more brazen orchestration in the music paired with drumrolls and cymbal crashes as Porky whips his head around to face Pinky again heightens the urgency and refines what was laid out in Porky’s Naughty Nephew.

Whereas Porky blames the impact on flies in the former, settling back to sleep before Pinky smacks him again and Porky heaving a dubious shrug as a result, the Porky in Picnic goes straight to the shrug. Here, the shrug is more serviceable as a reaction rather than serving as its own funny beat in Nephew, slower and armed with a “wah-wah” trumpet score from Stalling (as well as a comparatively funnier facial expression.) Here, Clampett keeps things rolling.

Pinky’s second attempts to toddle back over to Porky are much faster, seeing as the charade has already been laid out once before and solidified the audience’s expectations of what’s to come.

A major difference between Nephew and Picnic comes from Porky’s reactions the second time around. Porky almost catches Pinky in the act in Nephew—it is here that he actually does through a rather stilted motion of him sitting up. Though the movement is meant to be abrupt, it feels rigid; there are too many in-between drawings for it to feel caricatured, but no follow through to ease the animation along and make it flow better. Nevertheless, with brusqueness as the goal, it is certainly achieved.

Both Mel Blanc and Berneice Hansell are in tip top voice acting form upon Porky’s confrontation with Pinky. Blanc’s “Eh-peh-peh-Piiinkyyyy… wuh-weh-wha-what were you going to dooo?” is perfectly condescending and—for a change with Clampett’s Porky, always skewing on the oblivious side—conscious of Pinky’s motives. His ever present smile as he confronts Pinky is almost more threatening than any sort of scowl or angry outburst. Likewise, Hansell fully reigns in her sickening saccharinity as Pinky squeaks “I was jus’ going to, uh…”

Repeated smacks on the face with the wooden plank are a much more succinct explanation than any sort of excuse or line of dialogue. A cut to a wide shot is relatively smooth through having Pinky bludgeon Porky on both the close-up and wide shot. Smacking him in the close-up then using the wide shot to slip away would feel unbalanced, and waiting for the wide shot for Pinky to strike would create too long of a pause. Both scenes are bridged together perfectly, and the lack of any sort of music or dialogue completely plants the focus on the echoing, smacking sound effects of the board hitting Porky’s face multiple times. The echo of the sound effects in particular makes the hits feel twice as violent than they truly are.

With that taken care of, Pinky skips along his merry way, a jaunty sting of “You Must Have Been a Beautiful Baby” providing its own ironic commentary as Porky gawks on.

Even then, Porky provides his own insight on the altercation. Animated by the ever skilled Norm McCabe, Porky’s facial expressions are hilariously visceral, the awkward grin he flashes towards the camera reeking of rare insincerity.

“Eh-cyehh-cute kid!”

Clampett’s early Porky was typically a pacifist (that too would later change with the times, as Baby Bottleneck and Kitty Kornered make exceedingly clear), but even he has his limits. The cutting sound effect he does as he pretends to cut off Pinky’s head speaks volumes and makes for a very fun display; cute and innocent, seeing Clampett’s pig deliberately make loose threats of violence is an amusing and noteworthy rarity for the time. Directors like Bob McKimson, meanwhile, almost seem to take this scene as the prime inspiration for their interpretation of the character.

McCabe makes a clever cheat to account for the rare appearance of Porky’s neck. Rather than struggling to find a way to fit his bow-tie onto his neck and not seem like it’s aimlessly floating or attempting to hug the sides of his jacket, he’s instead drawn with a collar for as long as his neck is visible. It’s subtle and doesn’t feel like an outlandish addition; a smart and quick solution.

Porky’s acting seems particularly reminiscent of Oliver Hardy, of whom comparisons have been made between the two a number of times. McCabe appears to animate a similar scene in Africa Squeaks, where Porky heaves a particularly Hardyesque nod after screaming at the ambient wildlife to be quiet. Though his disgruntled resignation as he flops back into the hammock and contemptuously cocks a glance offscreen may be silent, it certainly speaks louder than any sort of snide follow up.

Enter the third act of the cartoon: the zoo. Now unsupervised, Pinky gaily skips along his merry way to the zoo (as indicated by comically gratuitous signage.) Rather than causing trouble in the moment, Pinky himself is the one landing in said trouble. As he skips along an alligator enclosure, he loses his shoe, narrowly avoiding the jaws of a sleeping gator. Animation of the gator snapping its jaws is cheated for maximum impact; the alligator closes its mouth while Pinky is on top of him, meant to prioritize the movement and appear that Pinky had a closer call than he already did. Treg Brown’s snapping sound effects continue to contribute severity.

Pinky thankfully reunited with his shoe unscathed. Interestingly (and disturbingly), his foot is cheated to look like a human foot rather than a pig’s hoof, likely to sell the purpose of baby shoes in the first place and make the action read clearer. Intriguing, the amount of cheats particularly concentrated in Picnic—they are by no means hinderances, but fascinating to view how certain problems are tackled, how certain movements are stressed, or how certain bits of clarity are strengthened.

Porky’s nap is disturbed when Petunia calls for help offscreen and urges him to do something about Pinky getting away, like the attentive guardians they are. Petunia’s animation again dips into the “aimless flailing” category, a lack of lip sync rendering the synchronization between sound and motion slightly discordant, but is—again, there’s that key word—energetic and serviceable for conveying her panic.

Always a fan of double takes or belabored pieces of character animation to render Porky somewhat of a lovable, oblivious klutz, Clampett has Porky pause to trip over himself in his hammock before taking off after Pinky. His falling is more of a side effect rather than a purposeful set up or a gag, a footnote to indicate urgency. The panic absent in Stalling’s music score thus far is present to hint at a real sense of danger; there won’t be any convenient railroad gates to halt any oncoming trains in this case.

Parallels are plentiful in Porky’s Picnic, whether to scenes already present in the cartoon itself or callbacks to previous entries. In the case of Porky chasing after Pinky, it almost gets to be a detriment—a shot of Porky passing the same “TO THE ZOO” sign feels slightly belabored and extraneous, as if slowing down his pursuit. A straight jump cut to him dashing past the slumbering gators would inform the action just fine. In any case, the up shot as he rushes past the sign pointing to the zoo is a welcome addition that does attempt to stress the drama of the situation through unconventional, “alarming” angles, though speed is a bigger demand that isn’t exactly met in this moment.

Likewise with the animation of Porky running and searching various enclosures of the zoo. Clampett would certainly refine his speed in just a matter of years (for comparison purposes, view a similar sequence from his The Henpecked Duck from 1941), but Porky here feels more as though he’s jogging rather than engaging in a mad dash. That too is solidified by a scramble take when he spots something in the lion enclosure, the take almost 3 seconds long of running aimlessly in the air. The context and tone are there, but a stronger animator could have aided the scene in reaching its full potential.

Nevertheless, Porky’s panic and subsequent scramble take are justified as the camera cuts to the grand reveal: Pinky lounging with a mama lion and her cubs. Rather than pulling a cliché and having the mama lion or her babies on the offense, preparing to strike a cowering Pinky, Pinky himself seems in control of the situation, willingly handing himself to a pack of bloodthirsty animals and seeing no problem with it. While the designs of the cubs are simple and literal for ‘30s cartoon standards, their round faces and head proportions help in making Pinky blend in with the pack. A wave from Pinky continues to rub salt in the wound; viewing him from Porky’s point of view, with the bars of the cage in the foreground, establishes a barrier and makes him seem even more out of reach—which, in turn, makes his wave come off as all the more taunting.

Carl Stalling’s musical accompaniment returns to a childish, happy yet subdued jaunt as Porky attempts to remove Pinky from the pack with as little fuss as possible. His entrance into the cage is yet another cheat, cutting directly to him approaching Pinky rather than showing a laborious sequence of him squeezing inside. Pinky’s rescue is priority.

John Carey is as good at capturing subtlety in motion as he is with distortions. Porky’s ginger removal of Pinky from the mama lion is certainly anticipatory through very slow, gentle movements; the audience feels the same visceral bated breath sensation that Porky himself does. Slowly, he manages to unearth Pinky from the clutches of the lions…

…until the mama lion swings at him with little warning. Therein lies the urgency missing in the prior sequences; Carey’s animation placed a heavier priority on motion and mechanics rather than polished character acting, and it pays off in this instance. There are no signs of the mama waking up as Porky approaches, no cracking of an eye open or snide glances at the audience. While it may be difficult to resist a funny glance or take from the mama lion, that restraint and waiting until the last possible minute for her to attack pays dividends and prioritizes the surprise factor so cherished by this cartoon.

An odd cut is made during a shift between animators; in Carey’s sequence, Porky rushes to the background with Pinky in tow as the lion chases after him, the camera panning a little too far past them. A jump cut is made to a different animator, with Porky and Pinky now in the foreground, camera right back in the middle with no warning. Likewise, the chase is animated mostly on ones to sustain the freneticism. At the beginning of the switch, however, the frames are held on twos, the end product reading as jumpy and slow. Once both the characters and camera catch up to speed everything is fine, the camera purposefully disorienting that audience as it pans to either end of the cage depending on who is occupying it when.

Clampett appears to borrow not from himself, not from his coworkers, but from the crew over at Fleischer Studios—specifically, Popeye—in the next gag of Petunia fainting admits the chaos of the fight. With her spinning on her heels and Porky fanning her awake, the scene is almost a beat by beat nod to Dave Tendlar’s Fowl Play from 1937, where Olive Oyl and Popeye go through the exact same routine (“Hey, this is no time to get romantical!”) amidst a brawl with Bluto. The specificity of the animation—particularly Petunia’s comically and purposefully stiff fainting animation—seems much too purposeful to be a mere coincidence.

Unlike the aforementioned cartoon, where Bluto fights with himself as Popeye helps Olive make a recovery, the lion has the courtesy to stop, providing one of the most amusing fourth wall breaks in the early Clampett years. Rather than anticipatory, fearful, the break is gorgeous; Pinky keeps himself occupied as the lion patiently waits, propped upwards against the cage. Porky grabs safely Pinky in his grip…

“Oh-uuh-uuh-okay.”

The chase resumes with absolutely zero fanfare at the exact same ferocity in which it was prevailing at before, a sign of success. Too much of a wind-up or too much preparation would lessen the spontaneity of the introduction and make it read as planned. That the momentum returns to the exact same pace—if not faster—is welcome and much less tedious than the alternative.

Porky and Pinky make a quick but rather unceremonious escape as Porky slips out of the cage, running past the camera and into the foreground. With the lion hot on the pursuit, she is instead catapulted into the bars of the cage in an elastic, intriguing bit of perspective animation. Lunging straight at the camera heightens the severity, especially on a big screen in a dark, crowded room. Having her lunge slightly diagonally (the direction in which Porky and Pinky also made their exit from) keeps the staging dynamic and natural; a full front view would be too rigid, flat, uncanny. The 3/4th view makes it feel as though she would lunge right past the camera and leap straight into the movie theater.

Typical late ‘30s screwball Clampett sensibilities prevail as the bars entangle the lion, hawking at the audience with a dazed, dopey expression.

Still caught in the momentum of fleeing imminent danger, a trip over a spare rock is what puts a halt to Porky’s fleeing once and for all. Instead, he skids to the ground, gathering a face full of mud as he holds Pinky high above his head and out of the way of danger. A similar maneuver would be reprised in Wise Quacks, with a baby duckling in place of a baby pig. Thankfully for the both of them, Porky skids to a convenient halt in front of Petunia, who happily grabs Pinky out of harms way and places him to the side.

When discussing the heroism of Porky Pig (or lack thereof) earlier regarding his oblivion to Petunia and Pinky sent hurtling towards an oncoming train, I mentioned that heroic clichés were avoided in that moment. Here is the opposite, where Petunia fawns over a bashful Porky and uttering those two magic words: “My hero!”

His efforts are rewarded with a full on face plant kiss that would make the censors squirm—quite literally, seeing as an article in 1939 was published discussing Hays Code guidelines and how Petunia and Porky are more of the “hand holding” romantics. Censorship guidelines mean nothing to Robert Emerson Clampett.

A predictable throwaway blackface gag reminds the viewer that this was a cartoon produced in 1939 and that no mud puddle is sacred.

In less derogatory news, the camera makes a return to Pinky, who perks up at something offscreen. The camera glides over to reveal the squirrel from before, its contented pose on the top of a toadstool particularly Disneyesque and cloying in its serenity.

As he did before, Pinky once again stalks the squirrel with scissors in hand. Casting Bobe Cannon for animation (seeing as he did the first shot of Pinky and the squirrel) succinctly bookends the two scenes together—now, the music is suspenseful, indicating a comeuppance may be in order.

Positioning the scissor perfectly around the squirrel’s neck, a death count for Pinky seems to loom on the horizon.

A comeuppance is certainly given—not from Pinky, but the squirrel itself as he smacks his perpetrator with a squirrel-sized plank of wood in the exact same manner that Pinky did with Porky. Same lack of music, same rhythmic smacks, albeit the sound effects of the wood here are much more tinny and snappy to reflect the wood’s smaller size. Likewise, the surprise is furthered through zero hints of the plank’s presence. Audiences could piece together the conveniently placed board of wood near Porky’s hammock—here, the squirrel whips it out at the absolute last second, and the end result is snappy, abrasive, and rewarding.

Schadenfreude is a delightful medicine. Overjoyed with his vengeance, the squirrel engages in brief, Clampettian cartwheels that call back to Clampett’s establishing animation of Daffy’s own hysterical Stan Laurel hops in Porky’s Duck Hunt. Iris out on an ecstatic squirrel and a tearful Pinky.

Porky's Picnic is one of my personal favorite Clampett entries of the era. It scratches a multitude of various itches: cute antics, engaging character acting, unrestrained energy, typical Clampettian boundary testing, and lots of slapstick. The short certainly has its moments where it falters--depending on the animator, some of the animation feels weak or disjointed, strong in its energy but weak in its coherency. The aimless flailing of Petunia and Pinky in the escapee side car is a good example, as are some of the sequences of Porky running through the zoo looking for Pinky. Likewise, blackface jokes never contribute to the betterment or quality of a cartoon.

With that said, the benefits trump the flaws tenfold. Picnic's prevailing attitude is one of unabashed mischief, its joyousness seen as a strength and not a flaw or immaturity. Certain gags or set-ups could go disastrously wrong in the wrong hands or with the wrong decisions: Pinky's sadism is much easier to stomach through his feigned innocence than it would if he were a cranky, contemptuous brat. A weaker director would have Pinky be consistently mean or have Porky constantly scolding Pinky. Not Clampett. In Clampett's world, slapstick is celebrated and blows are either shrugged off or withstood. Maintaining a joyous--albeit at times sardonic--attitude is much more palatable than watching Porky or innocent squirrels get the snot beat out of them for 7 minutes.

Engaging bits of character acting, primarily from Porky, make for a more inspired effort as well. Though Pinky is clearly the star of the show, Porky's presence doesn't feel obligatory or shoehorned (the same may not exactly apply to Petunia), and the jokes surrounding him extend beyond manipulation with his speech patterns. The hilariously pompous face he makes upon explaining he has a date with Petunia, the meticulous preparation at her doorstep, the idea of telling himself a fairytale for nearly a minute straight and completely oblivious to the absence of his company, and threatening to cut Pinky's head off are all very funny and earnest gags or acting decisions rooted in the sincerity unique to his character. His genuineness gets laughs, but is never set up to be made fun of or scoffed. Cartoons that preserve his innocence but maintain a hearty dose of sarcasm or humor are some of my personal favorite Porky cartoons.

The comparative unconventionality in Clampett's layouts are welcomed. A keen awareness of negative space, how environments interact with each other, framing and composition, as well as a smattering of unconventional up, down, or perspective shots all make the cartoon feel more immersive, more dynamic, and more engaging as opposed to standard flat comic staging. Carl Stalling and Treg Brown are further unsung heroes of the short's success; Stalling's accompaniment guides the action and provides its own commentary when necessary, as well as making easy listening (the recurring motifs of "Sticks and Stones" is one of my personal favorite arrangements from him). Brown's sound effects have the power to turn a mildly uncomfortable hit into a stupefying impact, as well as maintain the whimsicality in the direction through more innovative and less literal translations of the action at hand.

For a director who cherished the "cute meets violent" approach, this short is a fantastic example of what that looks like at its zenith without being wholly uncomfortable. Considering the slow decline and increasing mediocrity in Clampett's Porky cartoons as he grew more burnt out with the character, this is easily one of his best entries of the 1939 season.

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment