Release Date: July 29th, 1939

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Chuck Jones

Story: Dave Monahan

Animation: Ken Harris

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Pinto Colvig (Mountie, Engine), Mel Blanc (General, Dirty Pierre), The Sportsmen Quartet (Chorus)

After the high of Old Glory, Jones and his crew needed a break. Months of meticulously sculpted animation with much higher standards and visual grandeur than they—and the studio as a whole—were used to will inevitably wear one down. However, deadlines and quotas continue to loom, with little sympathy for an overwhelmed crew. Times like these often result in cartoons that are less than par to the standards of the director himself or the studio as a whole.

That is where Snowman’s Land enters.

Another attempt to focus purely on comedy and slapstick like his peers, whose attitudes reached successes by defying the stronghold of the Disney influence, Jones inadvertently continues to embrace Disney just as much—if not more—than shorts like Old Glory did. Prominently featuring Pinto Colvig performing his signature Goofy voice (as well as tame slapstick and meandering pacing) make such an argument. Now set in the Northwest snowscape of Canada, Snowman’s Land follows the escapades of an inept Mountie and his attempt to capture the notorious “Dirty Pierre”.

A signature Jonesian establishing pan is given the added benefit of rich vocals courtesy of The Sportsmen Quartet. With the typography of the title card dissipating, the audience is granted a picturesque view of a snowscape, pine trees overlaid in the foreground to further the illusion of depth. While the pan is lengthy, Jones’ attention to detail is not to be taken for granted; a keen eye can even spot an airplane in the distance skirting across the sky when the pan first starts. That, paired with the a capella arrangement of “Song of the Mounted Police” and vibrant brush strokes in the background painting themselves provide a worthy imitation of Disney’s own style.

Snowman’s Land is yet another rare early attempt at slapstick and more cornball humor from Jones. Already, signage above a cabin touting signature contradictories (“Dismounted Police”, get it? “We Always Get Our Man — Well, Nearly Always”, get it?) attempt to cue the viewers that this is no Old Glory.

Of course, both Snowman and Glory aren’t as far removed as one—perhaps Jones himself—may have hoped. Both subscribe to the Disney school of thought and differ only through execution and tonal priorities. Jones may have hoped that his witty signage outside the headquarters was more synonymous to the snarky humor so prevalent at Warner Bros., but casting Pinto Colvig as a dog-faced incompetent performing his signature Goofy voice does little to solidify a divorce from Disney’s influence.

Nevertheless, Jones’ knack for cinematic staging and exposition comes in handy, theatrics still in high gear as the camera dissolves to the interior of the headquarters. Camera pans continue to establish the setting: a general has his back turned to the audience in the foreground (a sign of both authority and mystery, hinting to a reveal), whereas a line of identical soldiers standing at attention purposefully disorient the audience through repetition and attempt to lock the audience into a pattern. Note the poster in the background possibly boasting a reward for the capture of Mel Blanc.

The camera pan comes to a halt only when cartoon etiquette has been breached; a smiling, puny dope strategically placed towards the and of the line indicates antics are afoot. His aimless, idle movements and glances already separate him from his rigid peers, all of whom seem to be battling a chronic case of rigor mortis.

In terms of design, the authority of the general is sourced more from his comically imposing mustache and stern expression more than his actual physical construction—very straightforward in design. A somewhat stuffy pause succeeds the finishing of his notes, foreshadowing the sluggish pacing that suffocates the cartoon. An attempt to eye down his peers reads more as idle activity in motion rather than a designated gesture.

Awkward pauses leech into Mel Blanc’s dialogue of the general himself, about a one second pause between “Gentlemen…” and “…we are confronted with a serious situation.” Blanc’s vocals are charming, albeit straightforward—similar to the general’s design itself, his timbre possesses little variation from Blanc’s natural speaking voice. Spoiled with the unique design (and speaking) style rife in the cartoon’s predecessor, Dangerous Dan McFoo, one finds it difficult to come down from that high and be reacquainted with Jones’ more comparatively conservative style of directing.

Nevertheless, the animation of the general is appealing, and the plot is promptly illustrated: a “scourge of the North” by the name of Dirty Pierre has been terrorizing the Canadian countryside. The general opts to display a picture of the fugitive for reference.

Jones does deserve credit for birthing a gag that would be used years on in the Warner cartoons: accidentally displaying a picture of himself, the general orates about “the brutality of his close set eyes, the vicious mouth indicative of a true killer”. A bored expression on the general’s printed face rightly serves as a nice buffer against his claims; the effect would be lost if the general were posing nefariously or even pompously. His stultified expression is as stark a contrast from the self described criminal type as possible.

“Observe the…”

Chiefly promptly dishes himself a serving of humble pie as he finally makes eye contact with the photograph. Though his surprised take and reaction glides slowly, the drawings are full of appeal, his sly grimace to the audience being pure Jones.

Rather than a “how did that get there” or any other meandering dialogue, the general moves things along with a silent chuckle, reaching for the photograph of the true Dirty Pierre.

Artistic value is high in Jones’ cartoons all throughout his career, but an especially keen eye for detail is present in his early work. The mugshots of both the general and Pierre are inked with lighter pastel tones in attempt to create the illusion of depth and make them read as printed images. While the pastel illusion worked best with the lighter palette of the general, the black ears and lines colored gray juxtaposed with the richer, darker brown fur of Pierre make him appear slightly washed out. Nevertheless, the detail is appreciated, likewise with the animated intricacy on the general (likely the work of Bob McKimson).

As his speech continues on, Blanc’s vocals grow more inspired, particularly on the general’s bloviated claims of “This man is a menace to society…” Unfortunately, that doesn’t detract from the awkward, seconds long pauses between lines. Likely they were included as a piece of character acting—the general wanting to ensure his men are paying attention, the pompous pauses allowing his words to sink in and authority to be emboldened—but instead read as accidental and sluggish, intentions unclear.

“Now, I want a volunteer.”

Tex Avery would reprise a very similar (and much more abrupt) gag in his Northwest Hounded Police over at MGM that is still one of the more amusing highlights of the short here: the Mounties, with no further introduction nor invitation, discard the scene by jumping out the windows, running off-screen, even diving upwards towards the ceiling. As such, the incompetent, dopey Mountie is left in a spinning whirlwind from the impact, crowning him said volunteer. Jones’ juxtaposition between the goofy Mountie and his peers is strong, not even limited to design and mannerisms but posing as well. When all of the Mounties are lined in a row, the majority are facing left. Our goofy Mountie faces right—a purposeful breach in rhythm.

Glacial pauses are continuous as the camera jumps to a somewhat bloated cut of the Mountie spinning to a stop. Thankfully, Carl Stalling’s music serves as an appropriate, melodic buffer: a stark contrast to the more situational scoring patterns heard in Dangerous Dan McFoo, Jones and Stalling place a heavy emphasis on melody. The background score is a continuous, bold march of “Song of the Mounted Police”, tying neatly back into the opening chorus but also containing enough variations depending on the action (for example, the music grows more bloated and lazy to reflect the Mountie’s spin cycle slowing down) to keep it fresh.

Vigorous handshakes from the general are bestowed upon the Mountie, who is mistaken as a willful volunteer. As is a recurring theme, the drawing style is appealing, though sometimes lacking in intent or motion; the Mountie getting jostled by the general is indicated through a heavy reliance on dry brush lines rather than the actual motion of his being jostled, which feels relatively leisurely.

Jones’ quirks are particularly noticeable on the acting of the Mountie: a brief moment where he adjusts his hat out of his face is synonymous to Tommy Cat’s repeated hat adjustments in The Night Watchman. Likewise, the Mountie performs a similar overzealous salute—rather than knocking himself to the ground like the former, he somehow manages to wrap his entire arm around his body, hat aimlessly spinning in the air after his hand brushed it for only a moment. The gesture feels forced, purposeful rather than a misstep on his part. Likewise, clumsy mannerisms such as these are typically employed to be endearing; so far, the Mountie has done little to earn that description.

“Get your man!”

Similarities to past Jones cartoons ensue as the Mountie gawks at the general’s extended finger (before, logically, perching himself on the finger), relatively similar to Sniffles’ inebriated fascination with his own finger in Naughty but Mice. Again, the nuance and subtlety of the former example are not exactly carried over in this specific cartoon.

Looking at a handful of the backgrounds (particularly inside the cabin) bring context to Jones’ likening of the ‘30s background painting style to “moldy prunes”. Much of it is a result of the painter itself and not the presiding style of the time (see Dick Thomas’ work in the Clampett unit for example, whose brushwork is much more controlled and less aimless), but the amalgamation of hues and colors in the wood paneling makes the paint read more as muddy and busy rather than serving as an accent of color. With all that said, it is nice to see story man Tedd Pierce get a cameo on a wanted poster in the foreground.

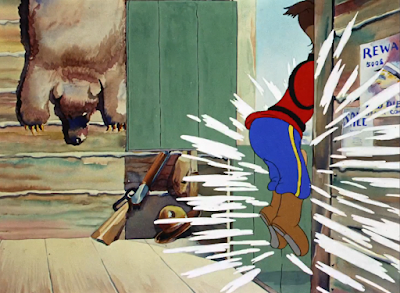

Armed with a brazen orchestral fanfare, the Mountie sets off on his journey. The audience braces for the upcoming routine, the slow execution as the Mountie opens the bottom half of a two way door doing little to conceal any sort of surprise exit.

The inevitable happens not once, but twice as the same exact routine is repeated in the inverse. Thankfully, tripping over the bottom door provides the Mountie a means of getting outside and finally moving the cartoon along. Jones’ earlier cartoons aren’t always as sluggish as they are made out to be, but this particular entry doesn’t do a great job of countering those critiques.

Rather than segueing into a bloated sequence of the Mountie struggling to rise to his feet, he is instead met with condescension from one of his fellow Mounties, a similarly scrawny but capable dog. The goofy Mountie is raised to his feet as his partner steps on his foot and raises him like a rigid plank of wood; pacing continues to be sluggish and animation awkward. His partner walks past, shaking his head, but the rigidity of the shake and blank expression almost make it read more as a technical gaff rather than a willful action.

An aimless take whose intention is unclear is followed by signature Pinto Colvig “a-hyuck” laughs. No dialogue to succeed nor proceed it—just to show off that he is armed with the voice of Disney’s beloved Goofy.

A cross dissolve indicates a shift in tone as the Mountie approaches his dog sled; pedals and ignition, as revealed through a close-up, adhere to a time honored tradition in the late ‘30s cartoons: modern meets antiquated.

Credit must be given where credit is due: though the animation of dogs repeatedly jumping up and down like gears is crude, the reliance on directionless motion lines slightly cluttering the composition, the rigidity also works to the gag’s advantage and does convey the mechanical motion that is so desired. Likewise, Treg Brown’s engine sound effects (the engine revving sounds provided by Colvig himself) further illustrate the illusion where motion may fail.

Jones’ dog themed antics do slightly veer on the cruel side with a literal meaning given to a choke valve. Though the gag would be reprised for cartoons to come (such as the ending to Bob McKimson’s Boobs in the Woods where Porky uses Daffy as his engine and repeatedly chokes him), the execution comes off as more painful than playful as a motorized hand physically chokes the neck of one of the puppies. Mainly, the gag capitalizes on discomfort through the dog’s face turning red and making choking noises; the straightforward, glacial execution muddies the creativity of the gag by putting a priority on pain rather than mischief, whether accidental or not.

Nevertheless, the dog-powered sled is ready to go as the Mountie shifts it into gear, again embracing standard gags pioneered by directors such as Tex Avery. Though the spirit is there, the speed is not.

A fade out to black and fade in signifies yet another tonal shift: that is, a song. The Mountie tries his hand at his own rendition of “Song of the Mounted Police”, Goofy-isms in full swing as a-hyucks and loud singing are plentiful. A brief halt in musical orchestration is noted in-between verses, as though only one verse was recorded for the backing track and they decided to loop it again. Jones certainly had stronger song numbers in his day, but the novelty of having Colvig on board is hard to dismiss, even today.

Moreover, the second half of the song is used more as a means of a backing track rather than a focus. While the Mountie warbles away, the pan speeds up and arrives at one Dirty Pierre himself, picking his dirty fingernails with a knife by a nearby tree. Posing next to the wanted poster ensures that the audience knows who the bad guy is. All things considered, the doppler effect on the Mountie’s vocals as he grows out of reach and eventually comes forward is a clever addition.

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of the Mountie’s confrontation with Pierre is not the conversation itself, but the background music. A prototype version of a common Carl Stalling motif—likely his own original arrangement—can be heard in the background as the Mountie asks if Pierre has seen Pierre. The music is mischievous albeit quizzical, inquisitive; it plays prominently in A Wild Hare and a vast variety of cartoons to follow. Though the arrangement here varies slightly, the similarities are certainly uncanny.

Dirty Pierre tells the Mountie he has not seen a Dirty Pierre; Blanc’s vocals for Pierre are somewhat more inspired than the general’s, introducing one of the earliest examples of Blanc voicing his stereotypical French accent. A take from the Mountie seems to indicate that he’s caught on, perhaps catching note of the wanted poster behind him, but no such luck, only asking if Pierre is sure.

Bob McKimson’s animation thankfully provides a visual buffer for the vocal fodder on-screen. Jones’ cartoons tended to verge on the wordy side—especially when he was armed with the writing prowess of Mike Maltese in the later ‘40s and ‘50s—but hardly felt as meandering as it does here. Then again, to compare the peak of his career after years of experience and experimentation to a cartoon made not even a year after he first started directing is an unreasonable and futile task.

On the topic of similarities to A Wild Hare, Tex Avery would refine a sequence similar to this one where Pierre takes great care to position the Mountie in hearing position and bellow in regards to the Mountie's queries of whether or not he's sure: “YES!!!!”

Avery’s take (as one might expect) on the gag is much stronger in its foundation, with a solid build-up and strong delivery from Blanc—whose yell here mainly constitutes as loud talking—but Jones’ trial here is interesting in itself and intriguing to see how it would be spun and evolved by his peers.

Signature, early Jones wobble takes ensue, distortions not reading as clearly due to the slow pacing of the Mountie’s animation. Chronic dry brush lines continue to clutter the movement as a graphic embellishment and not as a functionality.

Though the short’s pacing is frustratingly lethargic, it does—ironically—strengthen the next gag of Pierre readying to smack the Mountie over the head. Deliberately ginger adjustments to the Mountie (such as placing his hat in his hands, placing his fist gently on his head) serve as a nice antithesis to the refreshingly snappy impact of the hit itself. In an instant, the Mountie is immediately pummeled into the snow, granting his attacker a lumbering, glacial escape into a nearby cabin.

A dissolve back to the Mountie inadvertently indicates that a noteworthy amount of time has passed since Pierre made an exit; a jump cut would have worked fine. Nevertheless, the Mountie crawls out of the hole, befuddled blinks towards the camera and all.

A look down at his torso aids in stressing the cartoon’s namesake. Unsurprisingly, his shaking of the snow off his body is again lethargic, the energy conveyed more through Stalling’s flighty music score than the motion itself.

Though still glacial, a contrast between the Mountie’s vacant grin and a determined frown is refreshingly brisk. Likewise, Stalling’s laden piano glissandos accompanying the Mountie’s furious head shakes provides adequate—but not distracting—embellishment to the motion.

A push of the hat forward means business as our hero lumbers towards the cabin. Again, Snowman’s Land continues to either debut or feature a number of peculiar prototype trends or gags. When the Mountie approaches the cabin, he guffaws “Come out, or I’ll break the door down!” The camera cuts to a close-up of his face as he gives the audience a side eye: “An’ I will, too!” Such an addendum would litter golden age cartoons for years to come.

When Pierre refuses to budge, the Mountie is gifted yet another lumbering walk cycle, Stalling’s heavy musical score sounding purposefully adjacent to the Laurel and Hardy theme song; always an indicator of screwball antics.

Enter the ever reliable spinning leg take as the Mountie literally winds up for the kill. Jones gets points for creativity in terms of the visual metaphor, with the legs forming the image of a wheel, but the execution could fare better from snappier, more abrasive movement.

The impact of the Mountie mowing down the cabin is demonstrated in a wide shot, where Treg Brown’s echoing sound effects take priority. Animation fares well on the demolition of the cabin itself, though the weight and physics of the logs raining down from the sky after the fact are more synonymous to falling leaves or shrapnel rather than heavy logs.

Of course, cartoon logic prevails: the Mountie and Pierre continue to be separated purely by an upstanding door, with the Mountie struggling to pry it open. Pierre observing from a smug distance is of very Jonesian taste.

“Hey! Gimme a hand here, will ya?” Colvig’s dialogue sounds slightly stilted, though its intentions clear as Pierre pushes him aside. Again, the condescendingly amicable nature in which Pierre moves is pure Jones.

Rather than having Pierre give the Mountie a swift kick in the rear right then and there, meandering, unnecessary dialogue continues to persist to cement the stupidity of the Mountie. After a declaration of “Shucks—there’s no one in there!” from the Mountie, Pierre encourages him to take another look. By this point, the momentum of the gag has already been lost.

A kick is still a kick as Pierre sends his Mountie companion flying through the open doorframe. The Mountie’s befuddled take as he lands upright on his muzzle, slowly cracking his eyes open was a gesture synonymous with Jones’ earlier, slow period; a vast handful of variations on the gag have the added benefit of a stronger set-up or stronger impact.

More running takes ensue, with Pierre allowing the Mountie out of the door at again a very glacial pace. Drybrush littering the Mountie is—surprisingly—functional and does contribute to the betterment of his speed rather than being a source of clutter.

Falling into the snow and thusly rolling into a snowball yet again alludes back to the cartoon’s title as the Mountie is promptly excused from the scene. Pierre, meanwhile, finds it hilarious, the shading of his gut clutching yet again another indication of Jones’ school of thought. Whether in his animation or directorial work, Jones was fond of his shadows.

Any potential monotony from the snowball is slightly eased through perspective, the mass of snow rolling diagonally into the background and back into the foreground to further illustrate a feigned sense of depth. Its momentum is thankfully solid, all things considered.

While the inevitable of the snowball bowling into Pierre is certainly predictable, the action is yet again pardoned through comparatively engaging perspective shots of the snowball bowling past the camera. An added perspective shot serves not only as a bridge between two cuts but as a means to flaunt more perspective animation.

Much of the lethargy so prevalent in the cartoon leeches isn’t exclusive to the animation itself. Rather, the filmmaking. All throughout the short, dissolves and fades pepper the cartoon—though they are a fine way to indicate a transition, they often convey a passage of time and are slower by nature. Jump cuts can be abrasive, but considering the chronic languidity of the animation and pacing, a straight cut would allow the momentum to be salvaged rather than disrupted. As such, a dissolve to the snowball rolling down a hill and fade to black make the action seem much more relaxed and leisurely (if not disjointed) than a climax should be.

Fade back in from black to reveal the avalanche crashing into the Mountie headquarters, floaty wooden logs exploding into the foreground yet again. Treg Brown’s ear shattering sound effects continue to salvage the impact and embolden it—something that is very much needed.

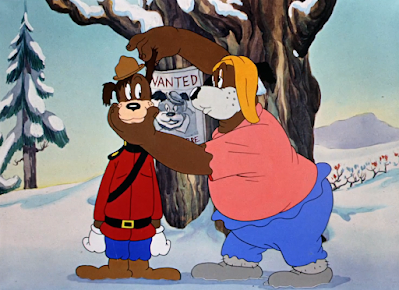

Stalling reprises a victorious march of “Song of the Mounted Police” as the camera cuts to a close up of the wreckage. Two dog-faced Mounties emerge from the wreck, mirroring each others shaking of the snow. To his a-hyuck-ing delight, the Mountie happily informs his general that he got Pierre.

Enter Pierre in snowman form, identifiable purely from the orange hat on top of his snowy head.

Jones’ ending is slightly aimless; for whatever reason, the general appears more terrified at the prospect of the Mountie capturing a snowman rather than a hardened criminal. He is quick to dive into the snowbank to seek refuge.

Perhaps even more confusing is that the Mountie mirrors the exit (with a lethargic double-take thrown in the mix for food measure.) Appealing animation pads the awkwardness of the sequence, but isn’t enough to hide its weakness.

Upon the Mountie’s exit, the snowman is left vibrating from the exposure of his speed, shaking the snow off of a dazed but contented Pierre. Iris out.

It is exceedingly clear that this is Old Glory’s successor in terms of Jones' filmography chronology. That is to say, one can visibly feel the burnout from the Jones team after giving their all into the aforementioned cartoon. With a runtime of nearly 10 minutes and filled with wall to wall meticulousness, it would be a surprise if the crew wasn’t feeling fatigued after such an excursion. Consequently, Snowman’s Land reflects the attitudes of the Jones team a little too accurately at the time: fatigued, relaxed, looking for something easy to churn out.

Some of the character animation is very appealing, and Pinto Colvig’s vocals are hard to grow tired of. Stalling’s music score places a heavy emphasis on melody and motifs, which makes for easy listening on the audience’s part. Likewise, Treg Brown’s sound artistry saves a lot of gags and elevates them where the animation or pacing itself may fail. However, the cartoon is a prime example of the chronic lethargy so many are critical of in Jones’ earlier works. Jones’ early works often get a hard rap (which is somewhat understandable considering just how strong his peak as a director was), but this cartoon in particular appears to embody a majority of the complaints so many harbor. The biggest one being—of course—that it is painfully boring.

The story itself is weak, and the languid pacing smothers any sort of inspiration. Jones taking the slapstick route becomes difficult to appreciate when the set-ups for such slapstick are meandering and slow. Pierre doesn’t pose much of a threat, the Mountie seems to make a point to be less and less endearing, and the general is bland and uninspired.

Perhaps the most intriguing aspect of the short is the number of prototypes it features. The general accidentally lambasting himself and describing himself as a criminal, the prototypal Carl Stalling music score that plays during the Mountie and Pierre’s initial confrontation, the early usage of the “And I will, too!” tagline, the choking engine gag, and so forth. I wouldn’t go as far as to say that this short firmly established all of these tropes without a doubt (save for the Stalling score), as there are perhaps other studios or other cartoons from the own Warner studio I’m misremembering that may have featured these gags as well in another fledgling form, but the significance still stands. Intriguing that such a meandering and painfully mediocre cartoon carves a number of important firsts.

With all of that said, much of these opinions stem from hindsight bias. It is all too easy to criticize Jones’ lesser works when knowing the heights that he would hit later on his career, as well as an understanding of future cartoons that have refined similar gags to bigger and better heights. However, there were cartoons from 1939 and beforehand—from both WB and its competing studios—that have been doing gags such as these and are to a higher standard than what Jones has here.

Nevertheless, Snowman’s Land has its small share of politely amusing moments and good qualities. It isn’t an overwhelmingly bad cartoon by any means, and to even call it “bad” would be harsh. However, it is painfully dull and slow, a solid showcase of why early Jones was as weak as he was as a director. Nevertheless, it is an oddly important cartoon in its own right, forming a number of fledgling ideas that would soon blossom and become golden age trademarks. It harbors a legacy that is confusing yet fascinating—much like the content of the short itself.

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment