Release Date: August 5th, 1939

Series: Looney Tunes

Director: Bob Clampett

Story: Warren Foster

Animation: Izzy Ellis

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Porky, Daffy, Duckling, Hawk, Dog), Bob Clampett (Mama Duck)

(The cartoon can be viewed here!)

Characters are bound to evolve as their filmography stretches forward, whether consciously or not. Sometimes the evolution is as noticeable as a design or noticeable trait change—other times, it’s very subtle and only noticeable through hindsight.

Daffy—who is still very much in his fledgling stages—has also made great strides in his own evolution, particularly through Bob Clampett’s handling of the character. No longer a mindless, shrieking drone whose only default is gleeful insanity, he now experiences a broader range of emotions and roles, needs and wants, personal touches, and so on. Recognizing that Daffy was continuing to make a name for himself and rising up the ranks, Clampett bestowed him with the greatest gift of all: a redesign.

Now armed with a gray mask around his eyes, the look would only persist for two more cartoons after this one, all by Clampett: Porky’s Last Stand and a cameo in We, the Animals Squeak! Though it would persist for a number of years in promotional art all throughout the early to mid ‘40s, Clampett’s team was the only one to use the design and drop it shortly after. Still, that there is even a drawing guide from the Clampett unit with Daffy toting such a mask is worth mentioning in itself.

Now that Porky has been briefly reunited with Petunia in Porky’s Picnic, Clampett opts to give Daffy a sweetheart of his own: the first of his many nameless (and often domineering) wives. Daffy would soon frequent the henpecked husband role, with Clampett revisiting the trope itself in The Henpecked Duck. Likewise, Daffy’s mingling with alcohol in this cartoon is yet another soon to be somewhat recurring aspect for the character. Slowly but surely, Daffy’s growth was becoming more permanent.

Upon learning the news that Daffy is expecting a child, Porky opts to congratulate his longtime buddy. He quickly stumbled upon an inebriated Daffy, having drunken himself into a stupor to cope with the stress of his wife’s “labor”. As such, when one of his ducklings is kidnapped by a hungry hawk, it’s up to Porky to save the day.

Dick Thomas’ stellar background painting serves as the first star of the show. The viewer has now come to expect that such a tranquil establishing shot is merely a ruse with Bob Clampett at the helm—a false sense of security to precede inevitable mayhem—but that certainly doesn’t negate the homeliness and beauty of the layout. Thomas’ solid understanding of value and contrast embolden the scenery and make aspects such as the flowers, trees, and moon pop out to frame the picture. Likewise, said boldness is also subtle enough to serve as a guide more than a statement. A demure string and flute accompaniment of “Home Sweet Home” sell the cozy notes.

A camera truck-in to the house yet again spurs Clampett’s own spin on a makeshift multi-plane pan; the painted flower overlay shifts left at a differing speed than the remainder of the background to indicate that it is on another plane of depth, enriching the composition of the painting and immersing the viewer into the setting.

To balance such a comparatively new trick for the Clampett unit (having only been used starting with Kristopher Kolumbus Jr.), the next sequence is a surprisingly well disguised piece of reused animation. Harkening back to the Harman and Ising era—particularly 1932—John Carey adds a fresh coat of paint nearly verbatim to a scene from I Wish I Had Wings. Friz Freleng would similarly appropriate it for Let It Be Me in 1936, albeit twisting the context to fit the needs of his own story.

As was the case in Wings, a mama duck (warbled, Clarence Nashesque quacks provided by Bob Clampett himself) contentedly knits a sweater, her purposefully cloying chorus of “Rock-a-bye Baby” indicating that a bundle of joy is imminent.

Carey’s dimensional, solid animation and appealing drawing style successfully refine the scene of origin beyond recognition for untrained eyes. Very little about the drawing style (perhaps save for the dotted line trails indicating heat as Mama stands to reveal a heat pack tied to her rear, but even the motion on the line trails is much more sophisticated) screams 1932. The only true giveaway lies in the timing and spacing of the animation itself, which shall be explored shortly.

Mama Duck flashes a sheepish yet proud grin to her loyal public before resuming her quack rhapsody.

Enter Daffy, sporting his new design embellishment as he peeks inquisitively from the coop’s entryway. His introduction is where the cribbing of previous animation becomes more apparent; though Carey’s animation has a tendency to be smooth to begin with, Daffy’s movements as he stares at his wife and approaches her when she coyly hides the sweater are more busy and evenly spaced than usual. Though weightless isn’t exactly the word, the mechanics of the animation aren’t as kinetic or grounded as what the 1939 Clampett unit was churning out.

Likewise, had the sequence of Daffy growing suspicious and insisting his wife hand over the goods been wholly Clampett’s vision, dialogue would likely have had a bigger emphasis. While visual acting and slapstick still had a larger presence compared to actual dialogue, it does become hard to believe that such a chatty character as Daffy would be one to succumb to a pure pantomime routine, especially when his emotions visibly permeate the screen.

Carey’s animation thankfully does a fine job of filling in the aforementioned holes. The drawing style and expressions from the characters are again appealing, and Carl Stalling’s music score in conjunction with the action itself provide a commentary where words fail. When Daffy thrusts his arm out, demanding his wife hand over what it is she’s hiding, Stalling accentuates his hand thrusts with a muted trumpet “wah” that melds into the music but is bold enough to provide its own voice. Mama Duck’s headshakes are additionally met with a more subtle musical glissando.

As the mother hen did in Wings, Mama Duck bashfully forks the half knitted sweater over before coyly covering her face, the motion again reminiscent of a bygone era. Carey at least paces the next bit of Daffy analyzing the sweater somewhat slower than the original in an attempt to make it feel more organic.

Much of the criticism isn’t all that noticeable given the context. Knowing the scene’s origins, it becomes easy to compare and contrast and see how the repurposing here follows the patterns of the source, which could be seen as anachronistic. However, to a regular viewer, it isn’t nearly as anomalous; one may question the decision to put such a heavy emphasis on pantomime (as seen particularly when Daffy nods expectantly at his wife, asking about the coming newborn through rocking motions rather than verbal dialogue—again, somewhat odd for a character so recognized for his annoying motormouth tendencies, even as early as 1939), but the reuse is masked surprisingly well.

Further reaffirmations from Mama Duck prompt a shrill “YAHOO!” from Daffy, a much more in-character repurposing of prior material. Daffy’s victorious leap in the air solidifies Carey’s handiwork as an animator—not only do the tall, slender eyes, prominent eyebrows and general solidity/sophistication in drawing style give it away, but the pose he strikes in mid-air is nearly a carbon copy of a similar take in another Carey scene from Scalp Trouble.

Daffy’s growth continues to be expounded upon as his filmography stretches forth. Worth noting is yet another foundational trope associated with his character—Wise Quacks would not be the first cartoon to feature Daffy as a (incompetent is putting it nicely) father. Friz Freleng’s Stork Naked, released during the height of the studio’s cynical comedy streak, bears a similar opening where Daffy’s wife is knitting a sweater for her soon-to-be little one. Rather than reacting warmly to the news and correctly guessing the hint, Freleng’s Daffy mistakes the sweater as a gift for himself and remarks on the size being too small. (Upon learning that he’s expecting a “visitor”, Daffy grows belligerent and vows to keep the stork away at any and all costs.)

Here, Clampett’s Daffy—like most of his characters—is on the naïve side. Perhaps that relates to the exposition being cribbed verbatim from a preexisting cartoon with preexisting characters, as Daffy’s competence as a father is soon called into question here as well. Nevertheless, no matter how overzealous, screwy or brazen Clampett’s characters get, there always seems to be a presiding innocence that aids in their likability. It may not be the most obvious nor entertaining aspect, but it certainly contribute to the good humor and mischief so rife in his early cartoons. Even Daffy at his craziest, most violent (The Daffy Doc) or most incompetent (as we shall explore shortly with Wise Quacks), he is armed with a necessary sincerity to keep the audience engaged.

In any case, good news requires spreading. A dissolve to a newspaper headline informs any audience members still clueless to the story just as much as it saves money through an absence of animation. Typical Clampettian sensibility ekes its way through various headlines and minute details: outside of the obvious pun between a bald eagle expecting heir, Clampett alludes to both gossip columnist Jimmie Fidler and—to a closer relation—Bobe Cannon (penned by his alternative nickname Bobo.) The “May 35” detail is more subtle, but in line with the Warner tradition of twisting nonsensical dates—see the many allusions to the ever elusive Octember.

Upon a close-up and vignette of the headline touting Daffy’s birth announcement, a familiar nasal stutter provides a voice-over: “Uhhh-eh-duh-dih-deh-dih-Daffy Duck’s expecting a buh-beh-blessed event…”

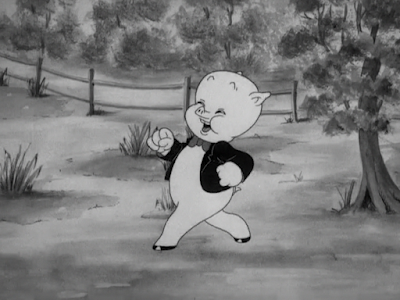

Mel Blanc’s amalgamation of thrilled bewilderment is palpable as the camera eventually cuts to the source of the commotion: “Duh-eh-deh-dih-Daffy Duck’s expecting a buh-bih-bleh-blessed evih-eh-vuh-vih-ehh… a baby!?”

Bobe Cannon is succinctly cast as the animator to convey Porky’s jubilation at the news, specializing in dialogue scenes that requires engaging acting. Likewise, the cuteness inherent in his style certainly pays its own dividends. Much of Cannon’s acting isn’t so much a solid string of grounded gestures as it is aimless prancing, but, for the needs of the scene, it fits, banking purely on the energy so strong in Porky’s blithering narration as he prattles on to an inert bloodhound.

“Gee, my eh-peh-eh-p-pal Daffy, a father…” Blanc’s vocals are the true winner; Porky’s unadulterated excitement feels wholly genuine, so much so that the aimless prancing and twirling as he carries on serves as a physical manifestation of his zeal rather than—again—a conscious string of acting choices.

“I can hardly beh-eh-beh-bih-beh-believe it. Why-why, we were kids together…!”

As mentioned in our dissection of Scalp Trouble, Porky and Daffy had already established their partnership with audiences as early as 1939. Though the context and subsequent background to these characters seems to reset with each cartoon (any sort of continuity sourced more from presiding characters traits rather than story or background itself), the two have made such a name for themselves and have been amiable enough together that audiences wouldn’t call into question the validity of Porky’s claims—especially considering the sincerity in Blanc’s deliveries. By the way he reacts to the news, one would genuinely believe Porky and Daffy to have the longstanding relationship that Porky himself alludes to. Likewise, such a milestone appears exclusive to their character—as has been mentioned before, their dynamic duo status and tendency to work together is an anomaly compared to other character dynamics.

Perhaps the greatest aspect of the charade is the abruptness in which Porky feels the need to politely excuse himself. His “Eh, pardon me” implies that he believes the comatose bloodhound to be hooked on his every word or itching to squeak a word in himself. Likewise, his polite bow as he excuses himself introduces a formality that is comically unnecessary.

Carl Stalling’s warm and peppy accompaniment of “Happiness Ahead” serves as an appropriate coda as Porky marches away offscreen, yet again an amusing juxtaposition to the brief formality seen as he pardons himself.

Very few characters could execute the same scene as well as Porky—his sincerity is embraced, if not encouraged, but poked fun at in a way that is endearing rather than callous. Only Porky would find it acceptable to breathlessly explain his life’s story to some random dog he found, then feel the need to politely excuse himself and leave with absolutely no warning.

Our barnyard bloodhound puts it best through his own deadpan, sardonic commentary towards the audience: “Amazing.”

Daffy, in a rare change of pace, does not share Porky’s jubilation. In another beat borrowed from I Wish I Had Wings, Daffy is now cast in the role as the nervy expectant father, pacing aimlessly outside the coop.

Clampett places enough of his own personal trademarks to call the scene his own rather than a borrowed plot point, but it certainly is fascinating to see a rare moment of vulnerability from the early Clampett duck. Had this short been made a year prior, Daffy would have been too hysterical and one-dimensional to care about the perils of fatherhood and his wife in “labor”. He may not have even had much of an idea of what was going on at all. For all we know, he would have been the cause of the stress to begin with.

To see him muttering inanely to himself (“I wish it was over with! I wonder what they’re gonna be… oh gosh.. oh gee, I wish this was already over with…”) and admitting he doesn’t know what to do is quite a step forward in development. Even in cartoons where Clampett’s duck did venture in other emotions aside from gleeful hysterics (The Daffy Doc or Scalp Trouble), he at least made an attempt at bravado and pretended to know what he was doing. To flat out have him say “I’m so nervous… I’m so nervous I don’t know what to do” is quite an admission, even if it is conveyed through circuitous ramblings with comedic intent.

Of course, this is the 1939 Daffy in question, whose hysterics and irrationality was still a strong defense mechanism. As such, he opts to cope with the stress by aid of a “bracer”: the implication that he even has his own secret stash of alcohol (colloquially and facetiously named CORN JUICE here, indicating the liquor is made with corn) is very amusing in its own right.

If Daffy as a deadbeat dad is one recurring aspect introduced in this short, then “drunkard” is yet another. A handful of cartoons would either allude to or make his encounters with alcohol a plot point (see the beginning of Daffy Duck Slept Here, where the “nice, levelheaded fella” drunkenly bursts into Porky’s hotel room.) In hindsight, it makes sense—of the flagship characters, it would be too abrasive and out of character for Porky, and a bit of a bad look for someone like Bugs (who is more the type to allude to the morning after.)

Daffy is eccentric, loud, extroverted, and brash, one who acts before thinking—it just makes sense. Though that sort of sophistication isn’t exactly present in his character here (who is purposefully made out to seem insane, the lack of a lip-sync paired with circuitous mutters making him seem unhinged and screwy), it’s certainly intriguing to see where recurring traits are birthed for certain characters and why they’re used as often as they are.

Nevertheless, one swig of whiskey quickly turns into three, Stalling’s musical score of “Little Brown Jug” adding its own ironic commentary through a slightly discordant, tipsy, laughing melody. Likewise, Daffy’s actions grow increasingly caricatured in movement as his dependency on alcohol grow stronger. His pacing gets faster, and by the third round he just zips backwards across the screen to indulge himself with no additional commentary. Though Clampett has undoubtedly placed his own brash spin on a sentimental trope at the core, the theming of Daffy’s alcohol reliance is hardly new—the earliest Warner cartoons in the days of Prohibition made a point to feature characters getting drunk as a means of anarchy.

On a related note, Daffy’s own anarchy has finally been achieved.

Dissolve to yet again a scene purposefully antithetical in tone: while Daffy’s anxiety has taken a more comic turn with the aid of some hooch, Mama Duck’s own trepidation is more forlorn as she awaits her babies to hatch. Clampett does a fine job of raising the stakes—between Daffy’s nervous father production and the somber alarm of Mama biding her time, it truly does feel like she is in labor rather than waiting for an egg to hatch. The tone feels very similar to the beginning of The Daffy Doc, where Doctor Quack lectures Daffy and struggles to get him to behave when operating on a patient (that is later revealed as a football.)

Of course, the tension in the aforementioned cartoon was relieved through screwball hysteria courtesy of Daffy. Clampett alleviates the tension here through Mama Duck’s curious shakes of an egg. When only hollow knocking sounds emit, she heaves a “what are ya gonna do” shrug at the audience before resuming her wait. Ironically enough, Clampett would repeat the exact same bit with Daffy in The Henpecked Duck only a mere 2 years later, the tone more inquisitive than foreboding.

To speed up the labor process, Mama Duck now employs the use of a nearby fire to warm her rear. The fire itself is amusing, but not nearly the focal point—Clampett makes it clear that other priorities lie ahead judging by just how quickly Mama returns to her babies.

Indeed, the true crux of the scene lies in the impending doom of her eggs nearly getting seared to death. To stress the potency of her heat, Clampett goes beyond the traditional steam lines and has Mama lick her finger to place it on her ass; a loud hiss of steam emanates from the contact, indicating danger. In pure sadistic Clampett fashion, Mama sees this as a victory rather than threat, preparing to park herself on the eggs…

“DON’T DO IT!”

The camera cuts in on a trio of hatched ducklings halting Mama in unison. A lack of musical accompaniment with their initial interruption makes their hatching seem all the more abrupt and surprising than it already is. Likewise, Stalling’s almost ironically saccharine violin score perfectly scores the eerily unified and temperate concession of “We’ll come out” from the babies. Having all of the voices be somewhat manly is a further amusing contrast—no stereotypically Mel Blanc baby babbling here.

Our newborn trio wipe their brows towards the camera in sweet relief. Frank Tashlin would reprise the gag in his own Booby Hatched in 1944 verbatim, exaggerating aspects such as the heat intake, amount of ducklings subjected to impending doom, and the synchronization as a whole, but the gag stands fine on its own here for 1939 standards.

For a more consistently chipper scene, the camera makes a cross dissolve back to Porky. One would almost mistake him for the father himself judging by how unabashedly jovial he is of the entire affair, singing “Rock-a-Bye Baby” under his breath as he struts on his merry way. Likewise, a simple snare drum march score and nothing else indicates that he is on a mission (as well as establishing a youthful, playful tone, again indicative of his personality.)

At this point, Daffy is completely lost in the sauce. Lazy, crossed eyes and a protruding tongue, as well as a generally lax pose are stronger indications of inebriation than they are of his screwball sensibility. Porky is either too kind to say anything or too oblivious to even notice—even after Daffy drunkenly cuts off his congratulations, Porky merely directs his attention to whatever it is that Daffy is pointing at rather than interrogating him. The quick glance back inside the coop that he spares before turning back to Porky is a very small but efficacious addition.

Enter the Duck family. With footage reused from Chicken Jitters—the only difference being the inclusion of glasses for Mama and one less duckling—the newfound clan strut to a jaunty backing track of “Concert in the Park”. All is well…

…until Porky points out that one of the babies hasn’t hatched yet. Further cost cutting measures are pursued as Porky is animated with his head away from the camera, carefully hiding a need to animate any lip sync with his dialogue. Bob McKimson would pursue this method in his own cartoons, and it was even used in the early days of the Porky cartoons where his stutter was too profuse to animate well. Here, it’s more Clampett being cheap rather than a lack of skill (especially comparing the angle between his head, the eye direction, and body), but is nevertheless effective.

Moreover, scale issues persist as the egg is twice as big in Porky’s hand in the next shot. Much like the cheat with obscuring his face, it isn’t distracting nor noticeable enough to be a major detractor so much as it is intriguing for analytical purposes.

Right on cue, the egg hatches to reveal the newest addition of the Duck family, animation again used verbatim from Chicken Jitters. As was the case with Jitters, Blanc’s purposefully cloying and infantile coos and giggles from the baby duckling add an amusing sheen of insincerity and polite fun at the purposefully Disney derivative acting on the baby.

Porky on the other hand is eager to indulge in the sentimentality. “Say, I’ll eh-buh-bee-beh-eh-bet you think I’m your eh-dih-deh-dad-eh-dih-deh-dad-ehhh—poppa, heh heh. Don’tcha?”Clampett continues to pursue cost cutting measures by reducing Porky’s dialogue to a voice-over, but the decision is seldom a detraction. Worth reiterating is the charm and sincerity in Blanc’s vocals for Porky in particular; he provides a good buffer for the coy—but very much cute—posing on the baby duckling, oversized eggshell hat and all.

The baby duckling continues to put on the cute act, bobbing his head yes.

“No. Uh-uh.”

Having the baby immediately revert back to another cute pose rather than harping on Porky further is what makes the refutation such a success. No further follow-up nor questioning is needed—the quick, straightforward and honest execution is just as important as the gag itself.

To balance out the previous sequence’s saccharinity—both sincere and ironic—Clampett makes a return to Daffy, now bragging about his output (“I’m a poppa 4 times over! Ha! Yessir, I hit th’ jackpot!”)

Though John Carey’s lip sync isn’t the most accurate, it again contributes to the presiding theme of incoherent rambling so cherished by this cartoon especially. Daffy’s lack of lip sync is chronic in this cartoon especially to a willful degree, as though Clampett and his unit were attempting to mimic the Fleischer style of ad-libbing dialogue; an absence of a moving mouth makes the characters seem all the more colorful, at times mindless, and eccentric—exactly what Clampett was aiming for with characters such as Daffy.

On the topic of Clampett, he again provides vocals (more coherent this time) for his wife as she asks in a near-incomprehensible but sharp “Daffy? Have you been drinking?” A rolling pin on duty reinforces battle-ax wife stereotypes.

Carey’s animation of Daffy’s reactions are pure gold. He freezes, early to mid ‘30s style reaction lines indicating that the gears are trying their damnest to turn as he chews on her words.

“Drinking? Drinking?” Blanc’s shrill, confrontational deliveries further Daffy’s offense (and subsequent hilarity at getting so offended by the accusation), Carey’s eye for appealing expressions and poses meshing well with his voice. Poses are strong, limbs elastic and expressions potent as Daffy puts on his best aggrieved act. How dare someone have the nerve to challenge his authority—which, as we have seen, has such a long running track record of unquestionable success. “Me drinking!?”

Milking pregnant pauses works in the favor of the entire sequence, allowing both time for the audience to digest the scenario and convey Daffy’s laborious, inebriated pondering. Amazingly, the sequence is almost musical; Daffy’s belabored blink before shaking his head profusely aligns perfectly with the beat of a guitar strum from the backing track of “How Dry I Am”. Though musical synchronization wasn’t nearly as high of a priority as it once was for these cartoons, it was still very much employed in more subtle ways that can accent and serve the action best.

Knowing the baby duck’s bait and switch refutation just a second prior, the audience does come to feel as though they should expect Daffy’s response to follow the same pattern, but his shameless “Yes,” is such a joy regardless.

A signature Mel Blanc hiccup and “PWOIIING!” sound from Mama hitting her husband with a rolling pin furthers the aforementioned suspicions of the scene’s musicality, both aligning with a satisfying coda to the end of the background music. Elsewhere, Carey’s wobble take of Daffy’s head moving back and forth is refreshingly tactile and elastic as far as wobble takes of this era go. In all, a very appealing sequence from all accounts.

Fading to black and back in signifies a transition to the second half of the cartoon. It is then where Clampett’s shortcuts become more noticeable: animation of a hawk circling above the farm is directly reused from Frank Tashlin’s Porky’s Poultry Plant with no visual alterations for 16 seconds straight. In fact, the only difference between the two (outside of the music) is the poor film editing on Clampett’s part. In the original, the scenes of the hawk circling the farm and then swooping to the ground bookend a close-up of a hen trying to escape the hawk. Here, there is no padding between scenes, and a jarring cut from the hawk circling lazily in the sky to approaching the ground at full speed is executed instead.

Consequently, a clear disconnect in design sense is noticeable in Tashlin’s scenes of the hawk and Clampett’s interpretation of the bird. The hawk approaches the straggler baby duck (who falls on his head trying to view the hawk soaring above him, Clampett’s craving for cute continuing to make itself known), sporting a design that is much more streamlined and rectangular compared to the bulbous, geometric composition of 1936 Tashlin’s design sense.

Thankfully, Clampett has fun with the hawk; Blanc’s delivery as the hawk is grating, sinister (“Hell-o, bud! Wanna go for a ride!?”) but in a way that is mischievous and lighthearted rather than wholly threatening. The same could be said for his acting—winks, sneers, and so forth all illustrate bad intentions.

Baby duckling has already grasped the concept of “stranger danger”, sharing a dose of anxious head shakes no…

“Yes. Uh-huh.”

Such is the brilliance of Clampett. Repeating the same gag set-up three separate times in a short period of time grows grating and monotonous, but he executes each instance with such a felt sense of earnest and playfulness behind it that it gets hard to fault. In fact, the contradictions are funny all three times.

Dissolve back to Mama Duck, engaging in another Rhapsody in Quack, this time to “This Is the Way We Wash Our Clothes” as she does just that. The story points cleverly converge as the hawk is seen flying in the background, carrying a visitor.

Suspicions are confirmed through a cut to the duckling riding on the hawk. The animation is the same recycling from Porky’s Poultry Plant, only now with the added benefit of the duckling giggling “Bye bye, mama!” Blanc milks the cutesy giggles and falsetto perfectly.

As has been mentioned before, Clampett enjoyed the sincerity and vulnerability of his characters. That meant embracing belabored or double takes and celebrating the oblivious. As such, Mama Duck merely wishes her baby goodbye, going so far as to turn around and look at the hawk taking it away. No suspicion or questioning of where her baby is going and why—just pure autopilot thinking. Clampett embraced the autopilot philosophy (even if that does mean going on autopilot for a few scenes or cartoons himself.)

Mama thankfully snaps to her senses after minimal clothes washing, now engaging in a fit of garbled, quacking hysterics as she runs aimlessly back and forth. Spiral brush trails, sweat lines as she does a big take and generally balloon shapes hands possibly give this away as Izzy Ellis’ work, though not certain.

In spite of her spousal abuse previously, Mama enlists in Daffy’s help, who is propped up against a viscerally uncomfortable Porky. Though Ellis’ handiwork veers on the crude side, it is certainly energetic; Mama engages in a panicked game of charades, understanding the limits of her impeded vocabulary as she attempts to convey the hawk’s presence.

While he may be inebriated, Daffy at least has enough sense to go rescue his son. Drunken stumbles are amusing as he prepares to fly into battle (which is worth noting in itself—when is the last time we’ve seen Daffy fly? Though he will certainly continue to do it after this short, he’s made great strides in divorcing himself of his animalistic origins, competent beyond quacking, swimming, and flying. Interesting to bank on one of his core traits for the climax), vowing to get his little one back to safety—“Jus’ watch me!” Absent lip-sync again furthers the theory that the decision was purposeful and for aesthetic purposes.

Daffy’s ascent in the sky is surprisingly smooth and competent. As though he, Clampett, and Warren Foster (who wrote the cartoon) are aware that this in itself is suspicious, he immediately returns to guzzle down a few more swigs of whiskey. His dependence on the alcohol is again caricatured through backwards animation timed comparatively quickly, making it seem more abrupt and emphasizing the absurdity of the motion.

A chorus of signature “HOOHOO!”s signify that Daffy is back in form. Stan Laurel hops are mechanical, yet always amusing and endearing as he charges back into battle.

His determination reaches its zenith as he scrambles through the sky at lightning speeds, so much so that one wouldn’t think he had just ingested copious amounts of liquor. Dry brushed multiples and shooting the frames on ones creates the illusion that he’s streaking through the clouds as a mere blur. Stalling’s backing track reflects the action through an orchestration that is panicked but impassioned, determined.

A brief cut back to the hawk and the baby remind the audience of the stakes, convey a heightened sense of urgency through quick cuts, and ease monotony from Daffy’s flying cycle. As the music climaxes, it seems Daffy is in the final stretch, able to save his baby…

Freezing in the air to pant frantically like a dog, music suspended and all, remind us that it is Daffy we’re talking about. Between the reliance on Tashlin’s own cartoon for the hawk’s animation and loosely Tashlinesque montage cutting, similarities between this and a very similar scene from Tashlin’s Scrap Happy Daffy may explain such anecdotal comparisons.

Perhaps more relevant to the joke here is that Clampett himself would reprise the “stopping to pant frantically” set-up himself in his Baby Bottleneck to a much more rapid degree. Nevertheless, the start, stop, then start again format would get quite a lot of mileage out of both Clampett and his coworkers respectively.

By whatever intoxicated miracle, Daffy is able to out-fly his competition: a wide shot of him scooping beneath the hawk and flying in front of him is simple but clear. A bit of flickering peppers the screen towards the end thanks to an error with the cels, but Daffy is moving at such a rapid fire pace and at such a small distance it becomes difficult to notice.

Banking on the absurdity of the entire ordeal, Clampett continues to incorporate eccentric flourishes into the action. For example, Daffy skids to a halt in the air, standing as though he is touching solid ground. A whistle also comes to his aid; he certainly has the vocals strong enough to yell at the hawk to stop, and it isn’t exactly an issue of being heard. Rather, using a whistle and stopping the hawk as though he were playing a game of crossing guard is more whimsical, more absurd, and more humorous.

That the hawk actually obeys Daffy’s orders provides its own playfully absurd twist. Indicating that his bravado was a temporary exception and not the rule, Daffy himself is quick to default back to his intoxicated self, now leaning against the hawk’s chest as a means to hold himself up more than to keep him back.

“What’s th’ big idea?” A profuse bout of hiccups proceed the events of The Impatient Patient, where Daffy is roped into a Jekyll and Hyde routine when searching for a hiccup cure. Absent lip sync matches the ironic commentary from the recurring background motif of “How Dry I Am” and continues to feed into Daffy’s inane, mush-mouthed antics.

“Where ya goin’ with that kid—hic—with that kid—hic—with that kid—hic—with that—hic—with that kid, huh?” Though Daffy’s drunken posing is already amusing, the intent, gleeful observation from his little bundle of joy watching his dear ol’ pop is pretty funny in its own right. Ditto with the murderous glares from the hawk.

Instead of a coherent answer, the hawk whistles for his cronies off-screen. His whistle is much more confident (none of that brass whistle nonsense for him), the burly build of the hawk deliberately framing Daffy beneath him through sharp awareness of negative space. With his arm over top of Daffy and chest accounting for the side, Daffy is essentially boxed in and made to seem even smaller than he already is. A great indication of the power imbalance.

More scenes from Porky’s Poultry Plant come in handy as Clampett recycles more footage; in this case, an army of identically bulbous hawks take off from the cliffside, airplane engine noises and plane-like stances further caricaturing their own determination in pursuing Daffy. Though the designs differ and the motion is jarringly smooth compared to the movement dominating Clampett’s cartoons, his recycling is more coherent and freer of awkward cuts than previous attempts.

As the cartoon stretches on, it grows increasingly clear that the animators had fun manipulating Daffy’s drunkenness. His head turn as he peers at the oncoming hawks is belabored, wobbly, but in a way that is purposeful and comical—his squint and lolling tongue are small yet potent design details that certainly add a lot.

Daffy’s half-cognizant glance at the camera as he merely gives an “Uh-oh,” is on the ugly side, though it serves more as a comedic contribution rather than hindrance.

Doing what he probably should have done as soon as he got the hawk to stop, Daffy scoops up his little one and heaves a bout of panicked, giggly shrieks—Stan Laurel hops and all—before taking off. Very amusing to hear his signature laugh used more as a cry for help rather than a declaration of gleeful insanity; Clampett would implement that “defense mechanism” relatively often.

A somewhat fast cut between Daffy leaving the scene and to him being chased by the hawks suffers from an abrupt transition. Likewise, the frantic, wobbly running from Daffy veers a little too far on the crude side than what was intended, but nevertheless serves as a strong contrast between the bold determination of the hawks and incompetence of Daffy.

Nevertheless, the inevitable occurs as one hawk tackles Daffy by the legs and pins him down, duckling squeezing out of his hands and plummeting to the ground. The unquestioned treatment of the sky as a physical, finite space that can be stood or leaned on is both a clever cheat for clarity purposes and a subtle commentary on the “anything can happen” nature of Clampett’s environments. Especially considering that the duckling is able to plummet through the sky completely, though Daffy and the hawk remain suspended on the “ground”, as though the sky has invisible pitfalls leading to certain doom.

A close-up of the duckling smiling as it falls to its death is yet another subscriber of Clampett’s mantra of sadistic yet cute. Dry brush trails and plummeting airplane noises aid in conveying the severity of the fall more than the animation itself, but the danger is nevertheless present.

John Carey takes over animation duties as the audience is reminded of Mama Duck and Porky’s existence, both observing in petrified helplessness. Carey’s acting on Mama’s histrionics is particularly appealing on the motion front, whereas Porky’s take is more conservative but consistently appealing. Delegating a simple shiver take to Porky allows the audience to direct their eye to Mama; her furious quacking and rapid movements naturally draw more attention.

Meanwhile, baby duckling is enthused (“I’m flying!”), clapping in joyously oblivious celebration. Again a recurring motif to Clampett’s shorts, the duckling’s gleeful oblivion seems to make the situation all the more gruesome.

With Daffy in the hawk’s clutches (and drunk) and Mama Duck locked in a panic, it’s up to Porky to save the day. John Carey’s animation is continually attractive, with sharp posing and an even sharper eye for movement. Porky switching from pose A to pose B through means of some very subtle perspective animation—that is, he leans into the foreground as he readies himself—is a seemingly inconsequential decision that instead adds a lot of depth and solidity to both the characters and composition.

The scene of his catching the duckling suffers from an odd cut to a wide shot; him running, falling—another subtle indication of that vulnerability Clampett loved to give his characters—and picking himself back up to catch the baby all could have been achieved through the same rolling pan shown seconds before. Instead, the cut feels arbitrary and disrupts the momentum, almost reducing the clarity rather than heightening it.

Nevertheless, the audience understands that the baby is safe, as is displayed in a sequence of Porky skidding across the ground and into a nearby pond. Very similar to his rescue of Pinky in Porky’s Picnic, he holds the duckling above his head to keep it out of harm’s way.

A small snout, double eyebrows and generally more streamlined features give it away as Norm McCabe’s handiwork as Porky breaks the surface of the pond, duckling safe on his head. Water pouring profusely out of his ears or not, more cutesy giggles from the duckling assure that Porky has done a job well done.

Diagonal wipe to a more dire scene. Animation of Daffy attempting to outrun the hawks is reused from earlier, this time outfitted so that Daffy is duckling free. Clampett’s dependence on recycled animation continues to solidify itself through another repeated shot of an aerial farm layout from Porky’s Poultry Plant, this time used as a transition as the scuffle heads back to the ground.

A tongue still protruding from his mouth indicates that Daffy is not totally free of the alcohol’s clutches as he seeks refuge in a nearby coop. Airplane buzzing sounds continue as the hawks file in behind him, wings still spread and all. One hawk closing the door behind the commotion and nefariously flipping a coin like a mobster (highly reminiscent of a similar scene from I’m a Big Shot Now) indicate certain doom.

Evidently, Porky isn’t done playing hero—as soon as he is able to pull himself out of the water, Mama Duck grabs him by the arm and yanks him along with her, quacking incoherently all the while. Porky having to run on all fours before he catches his momentum is again a somewhat subtle but welcome acting choice, indicating just how much of their running is dictated by Mama rather than him. The baby duckling perched mindlessly on his shoulder is another cute and amusing addition.

Porky halts only to grab a nearby stick (really, a club) before being pushed forward by Mama; Bobe Cannon’s closeup of the family approaching the coop is much more appealing and well drawn.

“Hurry! In there!” Mama Duck’s quacks grow slightly more coherent as she urges Porky forward. Cute, cuddly Porky (minus the scowl) carrying a baby duckling on his shoulder while wielding a blunt object is a highly amusing incongruity.

“Eh-duh-dee-ee-eh-duh-dee-don’t push me!” Porky has remained silent all throughout the entirety of the climax, skidding through grass and dirt and nearly drowning in a lake to save a baby duckling from falling to its death—that he only decides to speak up against Mama’s literal pushiness is as amusing as it is confusing.

Cannon’s drawings are continuously attractive, especially of Porky. Ready to save the day, he opens the door, mallet at the ready…

A surprised take from all three of them indicate that tomfoolery is afoot.

Said tomfoolery arrives in the form of a drunken chorus of “How Dry I Am”, led by Daffy as he makes amends with his new buddies. Easily one of the most inspired sequences of the hawks in the cartoon yet, and a scene that is pure Clampett—had the rest of their sequences truly been this inspired and less derivative of outdated cartoons, one wonders just how much better the short could get. There are no attempts to match the hawks to the design sense of 1936 Frank Tashlin, which is where the beauty of the scene lies. Clampett is at his best when he doesn’t phone it in. The hawk sequences certainly do feel the most phoned in of the entire cartoon.

More henpecked husband/battle ax wife jokes ensue as the foreboding silhouette of Mama Duck is projected against the wall. Daffy, heaving a particularly shrill and out of tune ending chorus, is quick to deflate upon his recognition. Clampett’s choice to lose the background music does a great job of thickening the suspense and calling more attention to just how roisterous Daffy and his new buddies are.

John Carey’s animation serves as a bookend to his very first scene of the cartoon as Mama raises her rolling pin, Daffy preparing for the blow. Stalling’s melodramatic orchestral closing fanfare adds a welcome degree of sympathetic, playful sentimentality.

Luckily, the rolling pin strikes the bottle of hooch rather than Daffy’s head, Mama’s twirling flourish unnecessary but joyfully so. Sharpness of the musical timing is rewarding, as is Daffy’s expression—instead of looking relieved, he almost appears slighted, as though getting hit on the head would have been a better outcome. Iris out.

Personally, Wise Quacks is one of my favorite cartoons of the era. Though Clampett isn’t immediately thought of for his subtle character acting (rather, his off color characters performing off color antics, which this short has plenty to offer as well), the scenes that prioritize personality and character are my favorites of the cartoon. Such examples include Porky’s introduction as he breathlessly prattles on to the invalid bloodhound, failed attempts to bond with Daffy’s baby after it hatches, Daffy’s inebriated gloating about how he hit the “jackpot”, and so forth. Clampett’s lighthearted, playful yet tongue-in-cheek approach to the characters allows for the humor to be snappy and even abrasive at times but salvaged through a presiding innocence and sentimentality.

Likewise, John Carey and Bobe Cannon especially both flaunt their fair share of appealing animation. Cannon’s eye for character acting is helpful in maintaining visual interest and personality with longer dialogue sequences, whereas Carey’s elasticity and consciousness of motion gels well with Clampett’s mischievous direction. Carl Stalling’s music score is sharp as ever, Treg Brown’s sound effects are a valuable asset particularly during the climax with his airplane engine noises, and Dick Thomas’ background paintings are lush, illustrative, but never restrictive.

With all of that said, Wise Quacks does teeter on the weaker side. Such a heavy reliance on reused animation renders the climax weak and tedious. As has been mentioned before, recycling animation isn’t so much an issue as it is the application. For example, the opening of the cartoon is directly cribbed from I Wish I Had Wings, but is relatively unnoticeable to an untrained eye (aside from the mechanics of the movement and the decision to prioritize pantomime.)

Outside of adding the baby duckling on top of a shot of the hawk flying, Tashlin’s sequences from Porky’s Poultry Plant go unaltered, which provides a natural disconnect. 1936 Tashlin was a much different style than 1939 Clampett, and as good of a cartoon as Poultry Plant is (and it is a very strong short for the time) it doesn’t align with Clampett’s vision. The irony of the ending sequence with the drunken hawks—the one scene where Clampett’s mingling with the hawks was purely his own, even in terms of design—succeeding because it was closer to Clampett’s vision is not lost.

Either way, the cartoon is still incredibly funny and charming outside of its flaws. It certainly must have been successful in some way, seeing that Daffy as either a henpecked husband or drunkard would become recurring character traits of his for years to come. Only Clampett could get away with a short that places such a heavy emphasis on alcohol, violence (whether through spousal abuse or implied by the hawks), and even have Daffy brag about hitting the jackpot in regards to his children and still cover it in an innocent, cute, and fun disguise. That whimsy carries over into the filmmaking and is what often results in the most success.

No comments:

Post a Comment