Release Date: July 15th, 1939

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Tex Avery

Story: Rich Hogan

Animation: Paul Smith

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Robert C. Bruce (Narrator, Spectator, Referee), Arthur Q. Bryan (Dan McFoo), Mel Blanc (Stranger, Commentator), Sara Berner (Sue), The Sportsmen Quartet (Chorus)

(A link to the cartoon may be viewed here--the short is also available on HBO Max!)

If remaking the cartoon in 1944 as The Shooting of Dan McGoo (which may be viewed here for comparison purposes) isn't strong enough of an argument for Tex Avery's continuous growth as a director and striving not only to establish but perfect his own gags, the content of the cartoon itself here is.

Having been a director at Warner Bros since 1935, Avery has made quite an impressive repertoire of cartoons for himself. A number of them liken comparisons to his later work during his tenure at Metro Goldwyn-Meyer, but few bring about so many comparisons in such a thick concentration such as this one. Perhaps serving as the ultimate fore-bearer to the type of humor, speed, and general setting established by his later cartoons, Dangerous Dan McFoo is a particularly inspired retelling of the 1907 Robert W. Service poem, The Shooting of Dan McGrew.

Perhaps most notable, however, is the voice cast. Arthur Q. Bryan makes his animated debut as the eponymous McFoo, known to most people today as the voice behind Elmer Fudd. Though he rarely supplemented his vocal talents for anyone but Fudd (the guest in Chuck Jones' A Pest in the House being another exception), Bryan was a radio, film, and television hit whose animated appearances did little to reduce his work intake Staying with Warner's up until his death in 1959, Bryan's voice work was revered especially by Mel Blanc, who very seldom voiced the Fudd and refused to after his death.

Here, Avery concocts a particularly inspired burlesque of Service's original poem, faithful enough to the story in its premise but chock full with plenty of self indulgent, reality bending eccentricities and Avery signatures of both the past and premise. McFoo and a dog-faced Casanova fight to the literal death after the dog makes advances on McFoo's date.

Robert C. Bruce’s stolid narration of the poem in which the cartoon is inspired from establishes an authority and stoicism immediately refuted through anachronistic visuals. Bright, flashing neon lights make a point to assert the modernism of the cartoon, divorcing itself from the time period of the poem written 32 years prior. A “90° Cooler INSIDE” sign—monikers commonly placed outside of buildings to tout their proudly air conditioned status—further cements that this retelling is not one of great austerity.

“A gang of the boys were whooping it up in the Malibu saloon.” Truck-in and dissolve to said boys, all comatose and slumped over their tables, bars, and so forth. No movement of them slumping into position, no explanation, just a direct refutation of the narrator’s words. Carl Stalling’s honky tonk musical accompaniment in the background grows thick to indicate and replace the silence.

That is until the patrons grow rowdy, projecting themselves into the air, shrieking and cavorting aimlessly before flopping right back into their comatose positions with no further announcement. Avery’s timing is razor sharp and a solid fore-bearer to the work seen during his tenure at MGM. Likewise, a lack of awareness from the narrator cements the gag’s confidence and absurdity. Other Avery cartoons may have the narrator clear his throat and regain composure before going on with his oratorical duties; the here humor relies wholly on the patrons itself—the narrator merely provides an antithesis to make the zany reactions feel all the stronger.

“And the guy that tickles the ivories was playing a swing time tune.”

Stalling’s hokey, honky-tonk rendition of “Seeing Nellie Home” is yet again pure antithesis, the 1850s number as stark a contrast to the style of ‘30s swing as possible. Avery continues to assert the unconventionality of the poem’s adaptation through a visual gag of the piano turned into a typewriter as the player does his stuff. After the completion of each verse, the music falls silent, replaced only by Treg Brown’s typewriter sound effects as the dog pushes it back into place and begins another verse. The interruptions each follow a rhythm so that the gag is surprising, but not jarring.

Such is the perfect opportunity to segue into a brief song number. The Sportsmen Quartet yet again work their magic as a dog faced trio provide vocal accompaniment to the background music, distinguished through their top hats and snazzy suits.

…or so we are led to believe. A clever tight shot hides their tattered bottom halves, all spouting suspenders, ratty pants and clunky boots in pure Avery fashion.

A direct reprise from The Penguin Parade, the trio halt their singing to strike wild held poses, all struck in an instant. Similar to Penguin, the success is found in spontaneity, which is reflected in the filmmaking—no lingering pauses or acknowledgement that it happened. A lack of a music score brings the most attention to the abnormality; the singers merely resume as normal.

The Sportsmen Quartet are always a welcome addition to any cartoon, but their vocal harmonies are particularly rich upon the closing of the song. Avery seemed fond of having his singers scoop their ending notes to a song—a similar glissando scoop can be heard as far back as Avery’s Page Miss Glory. Intriguing to see how a supervisor’s direction leeches even into the vocal direction of the music.

Riding the momentum of “inexplicable absurdity”, the dog trio end their song with a hip thrust towards the audience before darting off-screen as though their lives depended on it, music confusingly panicked as they make an escape. It all unfolds so quickly and so unceremoniously that there seems little reason to question it—likely, the answer to the ambiguity of the scene was because Avery simply found it funny.

Avery’s filmmaking reflects the sudden shift to a more serious tone, Avery employing one of his signature pseudo multi-plane pans as overlays of tables and chairs in the foreground snake past the camera, making way to reveal a crowd huddled in the back of the saloon. A lone bottle of poison in the foreground possibly hints at the gruesomeness in the introduction of one eponymous Dangerous Dan McFoo.

Crowd members part to reveal a particularly puny dog eyeing a firm strategy for his pinball game, peers observing intently. Perhaps Dan may be one of the members lurking in the crowd—maybe the dog with purple eye rings smoking a cigarette?

A quick truck-in of the camera to the puny dog assert otherwise.

“Hewwo, ev’wybody!” History is made as McFoo dares to open his mouth, bearing a speech pattern Arthur Q. Bryan would capitalize off of for 20 more years.

Contrary to popular belief, Bryan didn’t make up the voice purely for his role as Elmer Fudd. He was found because of the voice—a veteran of radio, he was a mainstay on The Grouch Club, of which a series of Warner Bros produced short films were made. Bryan appeared in a number of them.

He was soon brought into the cartoon department, not unlike impressionist Jack Lescoulie, Grouch Club host and known for his impressions of Jack Benny heard in various cartoons (Daffy Duck and the Dinosaur being a previous example.) Courtesy of Devon Baxter, you can hear a sample of Bryan and Lescoulie here.Bryan would continue to get more radio success as a result of his animation work, which was a result of his previous radio success, appearing on shows such as Fibber McGee and Molly, its spinoff show The Great Gildersleeve (in which he appeared on before McGee), Al Pearce & His Gang, and so on. At one point, he was so prolific that he earned more money per cartoons than Mel Blanc (keeping in mind that he appeared much less than Blanc did.) To say he was an important addition, both vocally and historically, is putting it lightly.

“And watching his fate was his heavy date, the girl who was known as Sue.” Stalling’s musical accompaniment melts into a demure rendition of “Heaven Can Wait”, matching both Bruce’s narration and the appearance of Sue, a sultry but cute poodle who owes Charlie Thorson her design.

As is Averyian law, every female character that appears in a Tex Avery cartoon must speak à la Katherine Hepburn, vocals yet again supplied by Sara Berner. Avery’s reliance on the trope is, to a degree, more endearing than it is tired. One can almost feel his glee towards the prospects of engaging in more self indulgence.

Sue’s “I’m so happy to be here… rah-lly, I am,” establishes her more as an actor in a play rather than an active participant in the story. Likewise, her poses are graceful and perspective animation comparatively solid. Coy adjustments of her hair and purposefully alluring poses call blatant attention and make fun of her status as the romantic lead. Avery’s knack for self awareness has a tendency to be gratuitous at times (i.e. every “___, isn’t it?” sign gag in his MGM cartoons), but here it is more amusing than not.

A love of pinball continues to permeate Avery’s cartoons, whether it be as far back as Little Red Walking Hood (which, it serves mentioning seeing our circumstances, debuted the prototype Fudd to begin with) or as recent as Thugs With Dirty Mugs. In this case, one of McFoo’s lackeys encourages him to pull the level (“More! More! More!”) to an absurdly far degree, as revealed through a wide shot of the crowd now huddles across the opposite end of the saloon. The spotlight hanging over the pinball machine in the far corner sardonically calls attention to it, almost seeming to heighten its loneliness (for lack of a better word) and just how far removed the crowd is from the game.

Per the lackey’s wishes, Dan lets go of the lever, which nonsensically prompts the machine to gallop left upon impact. The rush of the cronies scrambling to the game indicates the urgency of the hit more so than any visual—or lack thereof—impact on the machine itself. Likewise, dynamic angles and intriguing perspective shots raise the stakes of the game rather than any sort of suspenseful hesitation on McFoo’s part. Whereas the sequence of Killer Diller pulling the lever back on the fire hose turned pinball machine in Thugs capitalized on realistic motions and gestures from Diller to complete the transformation, the absurd route is embraced here.

Said absurdity leeches into the mechanics of the game itself. Structured similarly to the sequence in Little Red Walking Hood where the wolf loses the pinball game despite his cheating (thanks to a random move in direction from the pinball), the pinball holes itself are the ones that cheat McFoo out of winning: they directly part sides, enabling the ball to fall directly in the “OUT” hole. The slight smears on the holes as they zip to the sides both stresses their urgency and asserts that the cheat is very purposeful, rubbing salt in the wound.

Pinball holes amalgamating back together continue to mock a bewildered McFoo, gaslit by his own game.

“I was wobbed! I was wobbed!” Signature Fudd-isms—or, rather, Bryan-isms—are swiftly established as McFoo immediately bursts into nasally sobs synonymous with the soon to be refined Elmer Fudd. A truck-in and fade to black from the camera almost seem to make McFoo more pathetic than he already is, shedding a metaphorical spotlight on his tantrum and then deserting him in the moment.

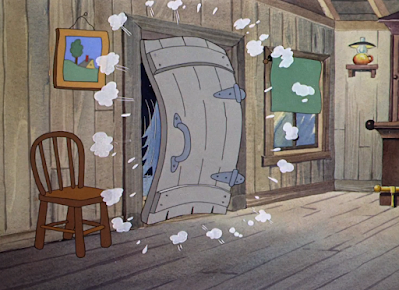

“And out of the cold—and I do mean cold—and into the light of the bar, there staggered a stranger fresh from the Gulf!” Bruce’s narration is considerably more spirited as the short lurches towards another tonal shift, this time one that is slightly panicked and foreboding. Avery makes a point to ensure the environments reflect the ambience; a snow squall picks up, wind howling, and said stranger is depicted only through a shadow trudging in the dark. As mentioned in previous analyses, Avery’s knack for filmmaking is a relatively under appreciated note to his successes; he understood ambience, atmosphere, and how to strengthen or refute a certain gag or set-up through dramatic composition.

Climactic, violent knocks on the saloon doors indicate the stranger means business. The door is knocked off its hinges and flops to the floor…

…where it is promptly turned into a cellar door, a smiling, dog-faced patron making an amicable entrance. Dangerous Dan McFoo precedes Avery’s MGM work in a number of ways: this very transformation would be refined to bolder, brasher, and more absurd standards in a number of years (see Little Rural Riding Hood.) Here, however, it’s plenty abrupt, confident, and amusing in its own right. As the years crawl along, directors such as Tex Avery and Bob Clampett continue to make the most of their animated surroundings and transform their environments into pure gag vehicles.

Another precursor to future Averyisms, perhaps one that is to a more iconic degree and synonymous with Avery’s legacy, is a prototype version of the signature wild, lustful Tex Avery wolf take. In this case, the take is delivered only through a handful of head spins from the dog, hat flying and landing back on his head, but is spirited and sophisticated enough to draw a connection.

Especially given the circumstances: the cause of his wild take is revealed through a cut to Sue, traipsing along the saloon.

Wolf whistles from the dog ensue as the camera trucks back out to a wide shot, surely preparing for more lust filled cavorts from the stranger. Indeed, Mel Blanc’s scratchy declaration of “What a PRETTY GIRL, WOW!!!” is nothing short of joyously ear-splitting.

In Avery’s MGM cartoons, his wolf would remark his ecstasy through a series of absurd, wild takes symbolizing his rampant lust. Avery and his unit here didn’t quite have the experience, ability or zeal present to find visually and engaging ways to creatively indicate the dog’s arousal. As such, Blanc’s vocals are as good a default as any to fill in the missing blanks—especially when under the direction of a supervisor such as Avery who knew how to adequately direct his voice actors.

Cut back to the pretty girl in question, prompting another hilariously absurd yet succinct transformation. As Stalling’s accompaniment of “You Oughta be in Pictures” rises into a bold crescendo, Sue is transformed into a metaphor of what the stranger sees: she melts into a visual of Bette Davis, whose looks were notorious enough to be likened to a sex symbol in this cartoon.

Not only does the photorealistic painting of Davis complete the transformation, serving as the most logical antithesis to the cute, cuddly, geometric appearance of Sue, but the Davis image bats her eyelashes in the exact same manner as Sue, linking the two together but calling strong attention to their differences. As an addendum on the musical front, Stalling’s faint flute trill every time Sue (real or in Davis form) bats her eyelashes is a welcome, coquettish accent.

More cartoon firsts weasel their way into the cartoon. Courtesy of our stranger, one of the earliest renditions of a character’s heart leaping out of their chest is immortalized through the coy posing of the dog, echoing timpani thumps marching in time with the bear of the music. Animation of the heartbeat is elastic and large, ensuring maximum potential for caricature. It pays dividends.

Continuing to foreshadow behaviors of the signature “Avery Wolf”, the stranger wastes no time professing his love and invading his victim’s personal space.

“Your eyes… your lips…!” Blanc’s brazen, screechy performance cannot be understated. In a way, the dog’s chronic screaming foreshadows the speech patterns of one Yosemite Sam. “HONEY, I LOOOOOOOOOOOOVE YOU!!!”

Yet again synonymous with all Hepburnesque heroines in Avery’s cartoons, Sue turns down the stranger’s proposal through pompous oration.

“Oh, please go no further…” Posing on Sue is strong in terms of silhouettes and ensuring her dainty, rigid posture. A reference to the 1938 Cole Porter musical Leave It to Me! is made as Sue quotes one of the show’s songs: “…because my heart belongs to daddy.”

A pause buffered only through Stalling’s piano flourish and another coquettish pose from Sue indicates that a joke was just made through her dialogue.

Seeing as our cartoon is entitled Dangerous Dan McFoo and not Dangerous Dan McStranger, McFoo reminds the audience of his presence as he catches wind of the flirtatious activity unfolding across the saloon.

McFoo’s confrontation is about as bold as one would assume. That is, not very. Hollow xylophone plinks accompanying McFoo’s finger taps on the stranger’s back makes him seem even more childish than what has already been established; a polite removal of his hat in respect and a “Pawdon me, but ‘dat’s my giwl,” do little to enhance his authority.

The camera makes a very quick pan left, both to place visual priority on McFoo and his adversary, but also as a sort of sardonic commentary, making the stranger’s outburst of “Well, WHAT OF IT!?” seem all the more uncalled for and abrasive.

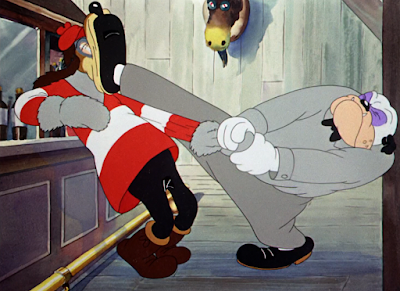

Disoriented from being screamed at in the face, McFoo awkwardly stumbles backwards, clutching his face. Thus segues to a close-up of the stranger grabbing McFoo’s middle finger and slapping him in the mug; knowing Avery and his own burlesque sense of humor, the assault was intended not so much as an intimidation tactic from the stranger, but more of a way to sneak a middle finger past the censors.

This means war. Bryan continues to pull every trick in the book that would later be synonymous with his performance as Fudd—in this case, aggressively nondescript nasal grunts. Just as it seems McFoo is about to physically retaliate, the telltale clang of a wrestling bell offscreen cuts him off. Not a metaphorical bell ringing to symbolize the brewing battle, but a true, physical bell, as indicated by the hesitation from both McFoo and his opponent.

Avery continues to exalt his speed and timing as a referee immediately weasels his way in between the two fighters, all in a matter of 4 frames. An increasing employment of dry brush streaks to convey speed and distortion reduces the need for extraneous motion or belabored run cycles. Likewise, his appearance isn’t challenged outside of the nonplussed glances from McFoo and the stranger. It’s all a part of the routine and Avery’s quest for transformative gags and set-ups. He’s made great strides since the early transformative breakthroughs seen in shorts such as Porky the Wrestler, and will continue to go to further lengths as his directing prowess strengthens.

More growth is displayed through musical means: that is, from Carl Stalling himself. Much like how the characters speak and sound, the musical arrangements in these cartoons will differ depending on who is directing. It may be pure hindsight bias, seeing as this cartoon is so similar to the shorts seen during Tex’s tenure at MGM, but Stalling’s arrangements in this cartoon at times feel similar to the musical stylings of Scott Bradley over at MGM. For example, scoring music behaviorally and/or situationally is given a heavier emphasis than arranging pop music tunes into fitting background music.

An example of a more situational music sting can be heard upon Sue’s threats towards the stranger. Her declaration of “You big brute! I hope Dan mows you down!” is scored with a nondescript, anxious violin accompaniment, set not to a preexisting musical tune but to Sue’s vocals themselves. This method of accompaniment would blossom as the ‘40s stretched on and the ‘50s especially for Stalling, so it is certainly nice to hear the beginnings of it now. Avery’s direction and input with Stalling is worth noting regarding the change.

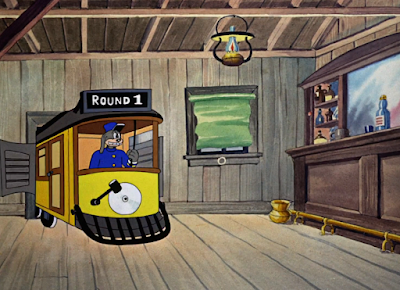

In Porky the Wrestler, a wrestling ring was transformed into a moving train after the opponent swallowed a cigar and bellowed smoke from his stomach. In Dangerous Dan McFoo, a literal streetcar bursts through the doors of the saloon, “ROUND 1” projected at the top, a dog using the trolley bell as a wrestling bell to start the fight.

CLANG! The distortions on the bell as a mallet strikes it are particularly impressive, the impact strengthened through smears and a plethora of graphic embellishments and lines.

As is the prevailing mantra with the remainder of the cartoon: no questions given, no questions asked. The beauty in the streetcar gag may not be the streetcar itself so much as it is the promptness and confidence in which it enters and exits.

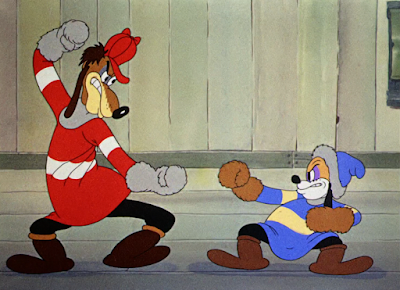

The beginning of the fight itself borrows relatively outdated concepts refurbished with snappy timing and dynamic drawings. Accompanying the brawl to an anticipatory score of “Poet and Peasant Overture” and timing the stranger’s repeated beatings to the music isn’t anything new by Warner standards (Friz Freleng did it back in ‘36 with When I Yoo-Hoo), but the execution and the confidence, dynamism, and straightforwardness of Avery’s approach is what makes it so special. Rather than having McFoo shower the stranger in a series of swipes, the stranger nonchalantly grabs his opponent’s head and rams it into his outstretched fist. Such caricatures the fight to make McFoo seem so powerless that other people have to fight on his behalf.

One of Avery’s many directorial strengths is his speed. His cartoons at MGM tout extreme bursts of speed, snappy, abrasive timing proving difficult to replicate by his peers. Though a number of his cartoons at WB have already begun to show signs of the sort of timing that would become a default, none of them have accurately foreshadowed the dynamism quite like the above fight scene. The employment of dry brush trails enhance the motion in itself, forming a simulated motion blur, but McFoo literally disappearing from one spot to the other with no in-between drawings brings the brawl to a new level of caricature seldom seen before.

Charades ensue as McFoo repeatedly dodges the stranger’s attacks, much to his bewilderment. Stalling’s start and stop musical accompaniment in tandem with the action further emboldens McFoo’s movements, staccato music cues representing his various switches from one position to another. The implausibility of his movements is further acknowledged when McFoo nonsensically pops under the stranger’s legs, but only after a failed punch causes him to jump. McFoo appears when the stranger’s feet touch the ground.

A brief stalemate is reached as McFoo and his opponent circle each other like hawks. The deliberate slowing of the movement stresses the abruptness of the fight before and after the mutual pause, a means of comparison in speed providing insight into just how rapidly their altercation was—and can—go.

More musical timing ensues as the two brawlers make a blatant disregard for the physics at hand; whereas McFoo’s pseudo-teleportation hints at nonsensical movements and physics, it could mainly be chalked up to a caricature of the speed in which he’s moving. Here, Avery ensures the audience understands that the reality bending is purposeful as the two stack their hands on top of the other’s, propelling themselves into the air.

Only the ceiling can serve as a buffer to their fight, indicating that they absolutely would have kept going until the last possible moment. Avery shows them falling to the ground through a quick, vertical pan, as seeing them physically falling makes the height (and absurdity) of the brawl all the more visceral. A jump cut to a shot of the floor would lessen the blow.

Avery briefly fakes out the audience by structuring the second half of the fight to mimic the first: McFoo and the stranger both locked in anticipatory defense positions, with the stranger raising his fist.

Instead, knowing that the audience has digested enough of the action to understand that there is a brawl going on, no more exposition is needed. Rather, Avery defaults straight to a whirlwind of dry brush, the occasional visible blow and smacking sound effects indicating that the flurry of movement does serve a functional purpose.

To see such a heavy reliance on dry brush is notable in its own right—the strokes are tightly controlled, which could honestly be seen as a detriment that lessens the spontaneity of the action, but it nevertheless serves as a reflection of the times. Had this cartoon been made a year or two prior, the action lines likely would have been opaque cel paint. The texture of the brush blends the movement together and simulates a somewhat more organic flow to an artificial means of caricature. Avery expounds upon the techniques he’s been using since his directorial debut with Gold Diggers of ‘49, now with more flow, control, and energy.

Hepburnisms make a return as Sue coos for her beloved Dan, perched safely on top of a nearby table as the fight zips into frame. That Stalling’s musical accompaniment is a circuitous reflection of the whirlwind and not a brazen orchestration of a piece of popular music is, again, more indication that growth is settling in.

Amidst Sue’s warnings for McFoo to be careful, more meta humor prevails, similar in vein to Porky halting a lion chase to recover a fainted Petunia in Porky’s Picnic (which was derivative of the Popeye cartoon Fowl Play, in which this appears to take stronger inspiration from.) With the whirlwind still flying, Dan squeaks out of the fight to weassuwe his sweetie: “Don’t wowwy honey, I’m not huwt a bit—an’ I’ll be wight out!”

Rather than willfully stepping back into the brawl, a gloved hand courtesy of the stranger reaches out of the metaphorical tornado and forcefully drags Dan back into the fight.

Having peaked at McFoo’s brief exit and entrance back into the tornado o’ fury, Avery knows not to try the audience’s patience with any more laborious fighting. As a result, the beloved trolley operator turned referee enters the saloon yet again to call a break, intentions of his visits left purely up to the signage on the streetcar. Dialogue would be extraneous.

Rather than repeating the same animation of the conductor striking the bell from the first round, Avery instead cuts to the action itself, the whirlwind taking off the ground as the flight climaxes. A bell clangs off screen, prompting the two fighters to halt in mid-air; a wide shot stresses the absurdity of McFoo and the stranger’s position in the air, making them feel smaller and almost poking fun at the ridiculousness of their circumstances.

Not only that, the wide shot accounts for staging reasons as well. It provides ample room for both McFoo and the stranger to daintily traipse down an opposing set of invisible stairs—as stark a contrast to the flurry of punches and hits as humanly possible. Stalling’s childish, descending piano score is a fine accent to the action.

Avery ensures that the fight is as transformative as possible. As a result, the stranger even has his own manager to help him warm up for the next round. The audience braces for a pep-talk from a burly manager: instead, they get an incredibly sharp routine of a barber giving the stranger a shave and a haircut with little fanfare. The sequence is surprisingly quick as is; one wonders just how absurdly fast it would grow to be had the short actually been a part of Avery’s MGM tenure.

Dan, on the other hand, is another story. Sue yet again fawns over a dejected McFoo pathetically slumped in his chair: “Oh, my dah-ling… are you hurt?”

Bryan’s pathetically jovial “Uh-uh!” and a shake of the head from McFoo is priceless.

Enter round 2. Our streetcar referee enters at twice the speed as before, Avery understanding that the audience has become accustomed to the routine by now.

Admittedly, round 2 isn’t as razor sharp in its timing or absurdity as round 1 is. Granted, the sharpness of the first round is pretty difficult to beat, but Avery appears to fall back into various gags and tropes seen before, whether by himself or his peers. The stranger shoving McFoo’s hat over his head and using him as a punching bag is clever, albeit anticlimactic—it succeeds a similar sequence from Avery’s The Sneezing Weasel, the drawing and animating style of both scenes relatively synonymous.

A heavy blow to the McFoo Brand Punching Bag makes a stronger case for Avery’s growth as a director: streaks of dry brush are used in place of in-between drawings, the actual impact of the stranger’s fist hitting the bat timed on ones so as to enhance its spontaneity. Stalling’s brief piano glissando as the stranger strikes into a hitting pose and Treg Brown’s echoing smack sound effects both perfectly accent the hit and make it feel much more potent than it actually is.

And potent, it is. McFoo is sent flying across the saloon and right into the wall, flopping back on the ground with enough rigidity to convey his obsolescence but a necessary amount of plasticity to keep the movement from reading as technologically wooden.

The next piece of business is more inspired as McFoo’s conscience rises from his body and fetches a pail of water. Disruptions or gaffs with the double exposure effects are minimal, if present at all—no blurriness or chromatic aberration, and Stalling’s ethereal musical accompaniment scores the Fake McFoo’s footsteps particularly well. Staging is simple yet clear with no arbitrary dialogue or acting.

Fake McFoo’s plans successfully revive Real McFoo, who seeks inspiration from his animalistic roots as he shakes the water off his fur, his angelic conscience reacquainting itself with its host.

McFoo now opts to use the downtime as a means to complain. Stalling and Avery both continue to employ their situational musical direction, a concerned violin score circuitously mimicking McFoo’s “Mistew wefawee! Mistew wefawee!”

Wefawee enters the scene as McFoo grows suspicious of the stranger’s fighting style, suspecting something padding his gloves. Bryan’s delivery of “I’m not the one to complain, but…” would be reused verbatim for Elmer in Chuck Jones’ To Duck or Not to Duck.

Rather than questioning McFoo’s claims, the ref instead confronts the stranger, who is reluctant to give up his gwove glove. Though the referee flopping out of frame suffers from too many evenly spaced drawings and not enough weight, the wrinkles—particularly the ones formed on the stranger’s muzzle as the referee places his foot on his mouth as leverage—are impressive and continue to indicate that Avery’s drawing style is evolving with the times. Organic shapes and construction are taking precedence over the spherical, geometric designs so prominent in the ‘30s.

Avery firsts refuse to stop as the cartoon presses on. Though the ol’ “horseshoes in the glove” trick was hardly new by 1939, having an entire horse—albeit a rather crudely drawn one—take residence in the glove certainly was. Avery would streamline the gag to much smoother, less awkward, and snappier lengths in his Lonesome Lenny later, but to see any prototype version of the gag is rewarding. Clunky as the horse’s design and movements may be, the idea of the horse itself is what the gag relies on most rather than the sophistication of the animation.

After more affirmations from Sue (both of the verbal and romantic variety) and a slightly misleading pause, seeming to prepare the audience for a gag that never comes, the brawl begins for a final time.

Instead of more attempts to charge at the stranger, McFoo opts to flee the premises after a spinning head take. Similar to the stranger’s entrance with the reality bending doorway, both McFoo and the stranger’s exits are executed through similar physics—a hidden doorway is revealed after the two exit from one end and come right back in the other.

With inspiration starting to ebb as the short stretches on, Avery employs ol’ reliable: a meta gag. Robert C. Bruce has been reduced to a mere observer as his narration has been no longer needed. Now, rather than orating a poem and introducing the characters, Bruce notifies the audience that the next fight will be shown à la freeze frames, “…to enable you to see the blows as they land.”

Mel Blanc takes over as the sports commentator, his grisly vocals synonymous with the wrestling match commentary in Daffy Duck in Hollywood. Excessive drybrushing is proudly flaunted (and for good reason), as are appealing, strong poses with clear silhouettes and dynamic lines of action. Blanc’s growling narration is spirited and mischievous, complete with awkward throat clearing sounds to account for his grizzled deliveries. At one point, the fight evolves over to the bar, where the barkeep is the victim of a hook to the chin (“Oh-oh!”)

After the fight sinks into a purposefully circuitous loop (“A hard right! A left! A right! A left! A right!”), the narrator himself decides to provide the brawlers with more lethal means of coming to a conclusion, perhaps an acknowledgement from Avery himself at the growing tedium of the fight. The pistols animated in perspective are solid and feel like a hilariously grave contrast to the rounded looks of the characters themselves.

One of the best parts of the sequence is how quickly Bruce’s narration returns to its stolid roots. There’s hardly any room for a pause between “Let’s get this thing over with!” and “They reached for the guns…”, though both deliveries are a stark contrast in terms of bravado and tone.

Narration returns as the story once again grows more faithful to the source material. “The lights went out…”

“A woman screamed…!” A spotlight settles on Sue, still perched atop the sanctity of the table. She inhales…

“…Eek!”

“And two guns blazed in the dark!” A metaphorical spotlight is shown on the work of the effects animator as neon, double exposed bursts of lights do their best to simulate the spray of bullets reverberating through the room as indicated through Treg Brown’s ricochet and shooting sound effects. Obscuring the bullets to instead shed literal light to a flurry of sparks is not only a creative choice, but one that is economical and heightens the impact—hiding the action allows the audience to imagine the bullets and brutality for themselves, which can always be made more gruesome through the power of suggestion. Showing the actual fatalities on-screen would be bold, but, if tasked by a lesser animator, may not reach the dramatics desired by the director.

A final pang and hilariously exaggerated moan (that, believe it or not, seems to be directly ripped from Young and Healthy—a Merrie Melody as far back as the Harman and Ising era in 1933— in a scene where the king cries over his broken jack in a box) indicates that a hit has been made.

“The lights went up!”

Stalling’s music score turns somber after the gun smoke dissipates to reveal a fallen McFoo, his own pistol still smoldering.

A tearful Sue mourning the loss of her beloved Daniel foreshadows perhaps a much more notorious variation on the set-up, where an Arthur Q. Bryan character is not the character being mourned, but the mournee—Bugs Bunny’s melodramatic death scene in A Wild Hare, animated by Bob McKimson. Though the sequence here doesn’t possess the same refinement and staggering subtlety that the latter does, it serves as a worthy forbearer, with Sara Berner’s sorrowful deliveries full of conviction and animation surprisingly solid.

“Dan, speak to me! Speak to me! Speak to me!”

“Hewwo!”

Iris out on a healthy, happy Daniel McFoo attempting to make pleasantries through his grin slash grimace.

As a personal anecdote, McFoo is one of my favorite entries by Avery during his tenure at Warner's--easily in the top 5. Though the second half does begin to lose steam, whether it be through prolonging the fight or a general lack of inspiration compared to the riotous first half, the short is an incredible feat for not only 1939 Avery, but 1939 Warner's as a whole. The level of caricature in movement and timing boasted by the cartoon hasn't been seen since Frank Tashlin was booted a year prior. Likewise, though Avery has had a number of inspired bits in the past year or so, he never hit the same threshold of speed and pure vigor that he does here. It genuinely does feel like a worthy introduction to the structure of his MGM work.

McFoo places a somewhat heavier emphasis on the story aspect than its successor, The Shooting of Dan McGoo, much to both its benefit and weakness. The story in McFoo lacks a solid structure, and the gags themselves can't entirely be depended on to carry the cartoon as they do in McGoo. As a result, an odd purgatory is reached, where the story aspect starts out seemingly strong and completely falters as the short carries on. Nevertheless, stories have never been a high priority with Avery's Warner cartoons, and the short is an exceedingly fun time all around. Sapped as the energy may seem in a handful of very fleeting moments, McFoo is leagues above the insipid travelogues Avery would churn out as a buffer to demanding shorts such as this one. For its time, McFoo is an Avery masterpiece and asserts a number of trademarks that would be refined to bigger and better lengths as time goes on.

.gif)

.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment