Release Date: August 12th, 1939

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Ben Hardaway, Cal Dalton

Story: Tubby Millar

Animation: Gil Turner

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Bugs, John Sourpuss, Dog), Pinto Colvig (Wheezes)

(The short can be viewed here, as well as on HBO Max for those who have it!)

The progression of Bugs Bunny continues to march forth. Not only is his more frequent concentration in the cartoons an indication that he is around to stay, but a total redesign solidifies such as well.

As shall be explored in the review, designer Charlie Thorson births a much cuter approach to the screwball rabbit—so much so that it only lasted for this cartoon. His next appearance, Elmer’s Candid Camera, would maintain similarities to his new, fuzzy gray design, but would appear somewhat more adult, taller... perhaps sophisticated is a stretch, but certainly more mature. Nevertheless, his legacy continues to strengthen its foundation as Ben Hardaway makes a return to his own creation.

As indicated in the cartoon’s copyright sheets, a (notably named) Bugs takes on a crotchety hunter, John Sourpuss, who seeks to hunt the rabbit in a means of rebelling rising meat prices. Screwball, hayseed antics are a plenty as Bugs finds numerous ways to heckle both him and his dog, but some of the methods he employs are more rooted in his future personality than one may believe.

Opening to a shot of a newspaper headline is as quick of a method as any to expose the synopsis. Signature Hardawayistic wordplay ensues with the proclamation of “MEAT PRICES SOAR — Consumers Also Sore!”, punny tagline emboldened to ensure the audience doesn’t miss it. A number of mildly intriguing articles and cameos pepper the paper, most notably a caricature of “Happy Hardaway” himself. According to ink and painter Martha Sigall, he was known around the studio as Smiling Ben Hardaway “because he never smiled much.” Other particularly intriguing details include a story about a riot that broke out at the Warner Bros Animation studio when Tex Avery was caught “dealing from the bottom of the deck” and a reference to “LU CAVETT”—Louie Cavett was a member of the studio who would evidently charge interest, deemed by Sigall as a card shark. Merrie Melodies get a shout-out in the corner of the rightmost page as well.

Enter one John Sourpuss, who lives up to his name through design—a prominent frown, menacingly purple ringed eyes, and a generally unappealing disposition (as revealed through his first action of the short; throwing the paper to the ground and declaring “THEY CAN’T DO THIS T’ ME!”) all sum up his role succinctly.

Physical distortions, wrinkles, prominent gums and otherwise erratic movements immediately give away Rod Scribner as the animator behind Sourpuss’ call to arms. Pacing around his living room to a gloomy score of “Then Came the Rain”, he claims to fight the meat shortage by bagging his own catches.

Typical for a Hardaway and Dalton effort, Blanc’s vocals aren’t as appealing as they could be—his crotchety, hayseed old man voice is at least energetic, but poor vocal direction renders it a tad grating on the ears. Thankfully, Scribner’s animation allows the entire sequence to be more bearable through spirited—if not grotesque—drawings.

Sourpuss’ transformation from civilian clothes to hunting regalia is mercifully swift; the hallway in his house serves as both a wardrobe and a means to prevent a laborious changing sequence. Gun in tow, he lets out a number of whistles, indicating a loyal canine companion is near.

Said loyal canine companion occupies closer quarters than the audience is led to expect. Stupid as it is that he pops up from beneath the armchair cushions (that Sourpuss was occupying just moments prior), it is a sector of stupidity that is blissful and enjoyable—often a rarity for Hardaway’s shorts. Its success is owed to its unceremonious delivery.

“You an’ me are goin’ huntin’!” Sourpuss’ dialogue is littered with awkward pauses or moments of hesitation, his addendum of “RABBIT huntin’!” slightly unnecessary and something that easily could have been added in the first line of dialogue. Nevertheless, another “I’ll show ‘em!” reiterates Sourpuss’ aggrievances with meat suppliers.

Dissolve to Sourpuss’ loyal hunting dog sniffing out rabbit tracks, Carl Stalling’s discordant accompaniment of “A-Hunting We Will Go” symbolizing the inevitable hijinks as unsubtly as possible. Sourpuss lumbers behind with a rather stiff, awkward forward facing walk cycle just in time to stumble upon the rabbit tracks for himself.

The filmmaking is somewhat disjointed, as a horizontal pan following the rabbit tracks and leading to the grand reveal may have eased the flow and maintained the suspense of the reveal more than a simple jump cut, but such matters are trivial; a freshly redesigned prototype Bugs Bunny littering the ground with fake rabbit tracks is where the true priority lies.

Instead of being a small, slender white rabbit, the new Bugs is taller, leaner, more anthropomorphic; he now touts gloves, an elusive yellow that would only be revisited with Elmer’s Pet Rabbit in 1941. His muzzle is tan, matching the inside of his ears, and his nose is a pink triangle rather than a bulbous black bean shape. The biggest change, however, is the gray and white color scheme, which would remain relatively the same for years to come.

While Thorson’s rabbit had a limited lifespan because it was seen as too cute and cloying, that is the only aspect that derives such comparisons. His personality is still very much that of a brainless, un-endearing heckler, and his hayseed Woody Woodpecker guffaws still persist in full force. Nevertheless, that his stamping of the rabbit tracks on the ground (and along both the top and bottom of a rock to display just how quirky he is) is silent save for Stalling’s chipper music score is a relief in itself.

That is, until he finishes the job—“a hurr hurr” laughs are plentiful as he clicks his heels together and zips off-screen in mad delight.

As has been mentioned in previous reviews, Hardaway admitted to Bugs’ existence hinging on the success of Daffy (mentioning to Martha Sigall that he would be putting that “duck in a rabbit suit”)—the difference between Daffy and Bugs’ antics are spontaneity. At his most prototypal, Daffy genuinely feels as though he is in the throes of insanity, his signature shriek and hysterical exits reading as a twisted form of catharsis. The proto-Bugs’ attempts at the same performance feels too synthetic, conscious, at times forced to be believable. It becomes relatively easy to note who is the imitation and who is the real thing—there’s a reason why this persona would not last.

Nevertheless, Dick Bickenbach’s animation (recognizable through the little marks that are expelled with each footstep) of the dog sniffing the footprints is less grating and solid. Reality breaking physics of the dog are continuously acknowledged as he disappears into the ground, resurfacing beneath the rock—the cloud of dust/dirt kicked up when the dog digs is rather crude, appearing as if the pooch is dissolved into the ground rather than actively digging, but the lack of self congratulatory acknowledgement of the delivery gains a pass. Some nice dry brush trails and overall energetic movement are on display as the pup turns its head, searching for the rabbit.

No dice. As the pooch moves forward, the rock still remains suspended in the air, supported only by the dog’s tail—Hardaway’s self control (or, more likely, Tubby Millar’s gag sense) is refreshingly strong as corny breakaways or admissions of the impossibilities are avoided.

Instead, the restraint is specifically held to build up to the climax: when the dog moves fully out from beneath the rock, it falls to the ground and sends the frightened pup into an anxious tailspin. While that by itself doesn’t sound exactly thrilling, the camera shake upon the rock’s impact with the ground (which has been the most realistic and impactful camera shake seen yet, sparing as they are) presents the scene with a novelty that is upheld with energetic, spirited yet solid animation from Bickenbach of the dog scrambling in the air.

He opts to take refuge inside a hollow log, which spawns more hijinks with the rabbit. Specifically, a scene that Tex Avery would borrow and refine to greater (and more amusing) lengths in A Wild Hare. Here, Bugs stands atop the log and covers the dogs eyes; “Guess who.”

The dog answers in a series of barks, all of which are refuted by Bugs, encouraging his prey to guess again. Whereas Tex’s—much quicker, one might add—take on the gag prioritizes Elmer’s responses and the absurdity therein, answering with a variety of female celebrities, Hardaway and Dalton prioritize the antics of Bugs himself. His “That’s correct! Ab-so-lutely CORRECT!”, borrowed from Daffy Duck in Hollywood and Daffy Duck in the Dinosaur, is supposed to be viewed as the main punchline of the scene, obnoxious guffaws serving as a key for the audience to laugh. The notoriety of the scene being tailored to fit A Wild Hare outweighs the crawling domesticity of the sequence itself. Again, another indication that Tex’s rabbit is superior.

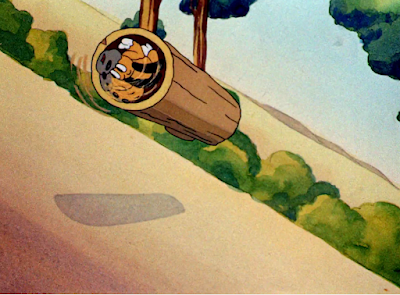

With the nonplussed dog observing from the sanctity of the log, Bugs uses this as an opportunity to kick the log down a hill. Another refreshing bout of camera trickery is employed as the composition turns sideways to account for the rising speed of the log. Likewise, both Dick Bickenbach’s multiples on the dog and visual embellishments as the log occasionally bumps into the air keep the scene visually engaging and energetic.

A handful of perspective shots are to follow. As the log barrels towards the camera, a collision against a nearby rock spawns a cut to the log further rolling downhill and into the background. That the log flies into frame from above the camera is a rather subtle but solid piece of perspective animation that immerses the audience into the cartoon. Though Bugs kicking a dog in a log down a hill is relatively lame in itself, the gag is made salvageable through comparatively quick cuts, mischievous energy, and palpable perspective animation.

A switch is made to Gil Turner’s animation (easily identifiable through the shiny, rectangular eyes, big jowls, and a big cranium on the dog) as he emerges from a now cracked log, a tree at the bottom of the hill breaking his fall. Dizzy lines and swirls are plentiful as the disoriented dog wobbles to an unsteady stop by a nearby dock, clinging onto the dock posts for security—the visual effects certainly get the job done, though Treg Brown’s sound effects to match are on the overzealous side and drown out Stalling’s drunken reprise of “Then Came the Rain.”

No matter—Doctor Bunny is on the case. Living up to the title card art (which is certainly odd in itself, seeing as Bugs is only ever in the water for this one scene), our star rabbit zips into frame with the aid of a motorized surfboard to stress just how much of a wild and crazy guy he is. Ditto for the doctor garb.

His forlorn head shake and condescending declaration of “Too bad…” mirror the same spiel from Daffy in The Daffy Doc—as has been seen in Hardaway cartoons of both the past and present, Ben was no stranger to borrowing lines, stories or gags from his colleagues.

Again, like the “guess who” scene, much of the attempted comedy in Bugs’ check-up on the dog (“D’you have dizzy spells? D’you see spots before your eyes? Do your ears ring? Are you subject to fits?”) is derived from the act itself. When the act itself is relatively weak—the scene is primarily carried through dialogue, as Turner’s animation in that moment is pedestrian at best—that doesn’t make for a solid argument for the gag to begin with. Even if it is all build-up for a punchline, there are other methods to make the build-up itself engaging and funny.

The grand reveal is a verbal punchline of Bugs conceding “So ‘m I! Maybe that’s what’s the matter with me!” With Hardaway at the helm, reminders of the characters’ screwiness are very liberal.

That too is nailed in the coffin through another canned fit of “a hurr hurr” laughter and floaty histrionics, which are eventually taken into the lake itself. Bugs plays blatant homage to his roots by mimicking Daffy’s hysterical water ballet in Porky’s Duck Hunt. As mentioned previously, the spontaneity that made such a scene in Duck Hunt so successful is not present here, rendering the sequence cheap and stiff.

In any case, John Sourpuss makes a return as he himself crawls behind a separate log on dry land. A quick but serviceable eye take indicates that he has found something worth of note off-screen…

…and indeed he has. Cut to a handful of rabbits frolicking in the distance, mechanical jumps accompanied by a quizzical clarinet glissando from Stalling. Every time a rabbit passes the second half of the screen, a cel overlay error occurs, with the rabbit’s foot clipping above the grasslands and not beneath it in perspective. Nevertheless, though the staging is simple, it is also very clear, the rock serving as a strong buffer between each half of the screen. Splitting the screen in half evokes symmetry and therefore traceable patterns, rhythm, which is always a welcome addition.

Sourpuss wastes little time firing at his prey. He hops over the log, more perspective animation touted as he jumps into the foreground and zigzags into the background, along the curving dirt path and behind the hill. For what it’s worth, Hardaway and Dalton’s staging is on the more inspired side, even if the animation or pacing itself don’t always meet the standards.

Such pacing issues could potentially be seen in the next cut; though it is slightly nitpicky, the reveal of the rabbits actually being an elaborate wooden contraption is held just a beat too long before Sourpuss tinkers into frame, slightly suspending the surprise. One would also figure Sourpuss to grow suspicious when seeing that the rabbits are still moving (and free from bullet holes at that), but such is life. His frustration is plenty marked upon realization of the ploy, throwing his gun to the ground in another fit of anger.

Another eye take directed off-screen possibly indicates that the real thing is nearby.

Bingo. Bugs’ taking a nap follows the principle of The Tortoise and the Hare, an indication of indirect but nevertheless smug superiority, as though Sourpuss’ pursuits are so ineffective that Bugs feels safe enough to let his guard down.

Sourpuss’ recruitment of salt—indicated by a close-up painting, which the Hardaway unit seemed to have a particular reliance on—follows the old superstition that salting a birds tail will make it unable to fly and thus easy to capture. Moreover, it serves as yet another allusion to the future Woody Woodpecker (if Bugs’ laugh didn’t drive enough comparisons): the first ever Woody cartoon, Knock Knock, has Andy Panda attempting to salt Woody’s tail to capture him. Ben Hardaway himself is credited as one of the writers for the cartoon.

Bugs’ instant zipping up into a standing position with celery in tow, fooling Sourpuss into salting his lunch rather than his tail, isn’t necessarily riotous for the celery itself more than the mercifully quick timing from pose A to pose B. No ordeal of finding a spare stalk of celery, no belabored sequence of him wrestling it out of his “pockets”, and so forth. Instead, we are introduced to the brief glimpse of a reality of where Bugs’ “What’s up, doc” is preceded by the chomping of a celery stalk and not a carrot.

“Celery. Mighty fine nerve tonic.” Bugs’ smalltalk is in response to the crestfallen expression of John Sourpuss. More self aggrandizing from Hardaway on just how totally crazy and kooky his characters follow as Bugs yet again makes it clear that he is, in fact, a screwball: “An’ boy, have I got nerve!”

Awkward tickling of Sourpuss’ chin with the celery ensues before Bugs jabs it in his throat and darts into a nearby cave. Stalling’s rousing rendition of “Corn Pickin’” is certainly an acute observation of Hardaway’s corn seed comic sensibilities.

Hardaway’s rabbit continues to thrive through impossible exits and maneuvers as the cave is now transformed into an elevator, with Sourpuss slamming against the closed doors. Thus furthers another staple first seen in Tex Avery’s Ain’t We Got Fun: elevator operator gags.

“Main floor! Leather goods, pottery, washing machines and aspirin.” More of the implied-to-be-funny-through-circumstance rather than proven-to-be-funny-by-running-with-the-situation humor prevails—Tex’s elevator gag in the aforementioned cartoon succeeds when an elderly mouse asks the mouse operator where the floor with the mousetraps are (sparking a surprised reaction from the mouse operator.) Here, no such clever writing is present—the gag banks its success purely on the circumstance, which is okay as is, but certainly feels as though it deserves something more. Such could be said for the entirety of the cartoon.

Bugs takes off in the elevator only to return and—yet again—assert that he is a quirky, kooky character who must instantly be seen as humorous through that and that alone. His “You don’t have to be crazy t’ do this,” is slightly too much, but would be fine on its own—the “…but it sure helps!” is typical Hardawayian overkill. More cornball laughter follows.

Another change of pace is signaled by a cut back to the hunter’s dog, again sniffing the ground for tracks. Bugs is now out of the makeshift elevator and back to an observing, hiding behind a tangle of rocks. A snap of his gloved fingers indicate that an idea is brewing.

Through the aid of a nearby bag (its floral patterns disrupted by sewn on patches at the bottom, yet another marker of Hardaway’s hayseed touch), Bugs makes animated history through his first performance in drag, prototypal or not.

In Daffy Duck and Egghead (which Hardaway wrote), Daffy was falsely lured in by a decoy. Here, Bugs IS the decoy. Through some restless yet peppy animation, he shimmies himself into a dog costume; the heavily dolled up facial features (eyelashes, lipstick, rosy cheeks) indicate that love is on the horizon. Bugs’ smoothing of the wrinkles on his costume is a nice touch (accented with a woodwind flourish from Stalling), and the brown patch on the top of his head is a creative placeholder/illusion for hair.

The pumping of his butt in the air before he prances off is excessive, but in a way that is welcome and purposeful rather than detrimental. No matter how experienced, Bugs takes his role seriously.

What follows is one of the cartoon’s high points, wonderfully animated by Dick Bickenbach. Bickenbach’s animation is solid, the movements of the dog sniffing the ground feeling controlled and confident rather than a bout of aimless motion. In the midst of his frantic sniffing, the (real) dog catches wind of incoming company and seeks refuge from behind a nearby rock.

Enter Bugs, dainty footsteps tinkering in time with Stalling’s playfully demure score of “Are There Any More at Home Like You?” The simultaneously butt and head swaggling action is a great pompous touch.

Not only does the dog checking both directions one last time add an amusing footnote, implying he’s expecting more sultry canines to follow, it is also timed to the beat of the music score. Signature Bickenbach reaction lines underscore the musicality of the motion.

Strong, appealing posing continues as the pup approaches his love interest, now sitting coyly on yet another hollow log and inviting the pooch to take a sit. Bickenbach maintains a strong rhythm between his varying poses.

Though subtle, a pounding heart take from the pooch solidifies his infatuation.

Stalling’s accompaniment takes a more intimate turn as the dog situates himself on the log. Allowing the camera to truck in closer not only promotes clarity and focus in their interactions, but also makes the scene seem more closed off, cozy.

A nearby bunch of blue wildflowers serve as the perfect makeshift bouquet. To the pup’s delight, his love interest is happy to receive the gift.

So happy, in fact, that she plants a kiss on the dog’s cheek.

Though the truck-out of the camera and stupefied flopping to the ground from the dog are both a little too slow, the lovelorn ecstasy of the pooch is nevertheless conveyed as he zips back up into a gleeful fit of silent hysterics. Such freneticism—albeit silent—possesses a sincerity that is absent in Bugs’ own hysterics. Even if they do pose different roles and personalities, the dog’s acting is much more convincing than most of what Bugs has displayed thus far. This has been his best scene yet—the one that relies the least on forced screwball histrionics.

Of course, all good things must come to an end; overcome by lust, the dog grabs his female counterpart and sweeps her into his arms, kisses at the ready. In the process, he only manages to grab the costume; Bugs does not seem affected by the mishap at the slightest.

Instead, it almost seems planned as he plays the role of the observer, his commentary of “Hmmm.. I think you got somethin’ there, buddy!” snapping the pup out of his daze. Bugs’ smug acknowledgement of a scenario he made himself, now playing the role of a not-so-innocent bystander, would yet again soon be a character trait synonymous with his image. Hardaway’s rabbit is the strongest possible antithesis to “sophisticated” as one could ever hope to find, but the blueprint—no matter how crude—is certainly taking form.

On the topic of sophisticated and the lack thereof, Bugs is quick to resume to his old “a hurr hurr”ing self as the dog chases after him. The chase now leads to yet another Bugs Bunny staple that would have plenty of chances to be refined to greater, more competent lengths: the disguise.

In this case, (entirely animated by Gil Turner), Bugs hides behind a nearby rock to let the dog pass him. In the midst of the pooch’s running—which admittedly isn’t all that fast, at times a victim to Turner’s bloated timing style—a siren can be heard whirring in the background. Enter one Bugs Bunny, donning a police officer’s cap and motorist goggles/gloves as he rides an invisible motorcycle into frame (another proclamation of just how nutty he is!) and stops the dog. The sound effects of the siren, brakes squeaking and kickstand being knocked into place are all welcome additions that ease the corniness of the illusion.

“Goin’ a little fast, weren’t'cha buddy?” Regardless of his talent as a voice actor, Blanc’s vocal direction and deliveries as Hardaway’s rabbit makes one long for the nasally strains of that Brooklyn accent.

Bugs continues to accost the dog (“Hmm! In-TOX-icated!”) in a relatively one-sided and meandering scene. The dog’s befuddled, scared reactions don’t provide much reason to be amusing, and the pacing fluctuates; Bugs’ “Let’s see your driving license! Hmm, just as I thought! Haven’t got one!” is rapid-fire, hardly allowing any time for the pup to react before he continues on with his accusations. Admittedly though, his follow-up of “You know what this’ll cost you? 30 days… has September, April, June and Montana; all the rest have cold weather, except in the summer, which isn’t often!” is so mind bogglingly stupid that it’s hard to hate.

Making yet another exit, Bugs’ stripping of his disguise is yet again accompanied by a chorus of obnoxious laughter.

Now beckons the song number portion. For this, a brief bit of context is necessary: as mentioned previously, Hardaway is given a writing credit on Daffy Duck and Egghead, Tex Avery’s second and most focused outing with the duck. As amusing of a cartoon as it is, there are a number of creative decisions and gags that are evident were the brainchild of Hardaway more than Avery. Perhaps one of the most glaring examples was Daffy’s song number, in which he gives a testament to just how crazy and screwy he is.

Avery had a fondness for self awareness, to the point that it could get exhausting (again, every “__, ain’t it?” sign gag.) However, if he has his way, he had enough restraint to prevent his characters from singing a sincere ode to their looniness. Such self-aggrandizement was not his style, especially not from his own characters.

That Bugs sings an entire song number here about just how positively crazy he is (aptly named “I’m Goin’ Cuckoo”, a vocal arrangement of a seemingly original score from Stalling that has played in the background of various cartoons) asserts that the song number in Egghead was very likely his own doing. Here, however, he doesn’t have the benefit of someone trying to tie him down to earth or take a more subtle approach. Though he co-directed alongside Cal Dalton, one gets the feeling that a vast majority of decisions were Hardaway’s doing.

It is about as unsubtle as it gets, a physical manifestation of every bad habit touted by this cartoon yet. At the same time, it is unfairly catchy, rightfully perky, and certainly a memorable highlight of the cartoon. Dick Bickenbach appears to animate the entirety of the song, save for a brief interlude where Bugs hangs from a fence by his feet, where some of the eye shapes as he hops to his feet seem possibly reminiscent of Rod Scribner (though pure speculation and nothing more.)

Catchy as the melody is itself, it also boasts a number of notorieties; perhaps the most egregious is the startlingly prophetic sequence of Bugs ripping apart a poster with Porky’s face on it, an eerily accurate precursor to the fates of the respective characters. Likewise, his lyric of “Please pass the ketchup, I think I’ll go to bed” would be partially reused in Bob McKimson’s Boobs in the Woods 11 years later. Bringing that closer to home, Bugs himself would sing a snatch of the same song here in McKimson’s Easter Yeggs, albeit with slightly different lyrics.

The song number is ended only through the abrupt appearance of John Sourpuss and his gun, who has been absent for the past 2 and a half minutes of the cartoon.

Sourpuss has had enough of Bugs’ act, dismissing the bunny's claims that he was “only foolin’”. Instead, Sourpuss promises that the rabbit will be sizzling in his frying pan by the morning. Rod Scribner’s animation, noticeable particularly on the distorted mouth shapes of Sourpuss and occasionally tapered eyes, at times verges on directionless, weightless.

Animator Herman Cohen takes the reins in an almost-but-not-quite POV shot of Bugs insisting he’s nothing but skin and bones. Such staging, with Sourpuss in the foreground and Bugs in the background, isn’t often utilized in the Warner cartoons, favoring more flat, vaudeville-esque composition for dialogue scenes or at least maintaining two characters in the same plane. To see such a breach is certainly interesting in its own right.

More interesting, however, is that Bugs’ skin and bones routine (grabbing his fur and appearing anemic) would be reused directly in Bob Clampett’s A Coy Decoy, further exaggerated to Clampett’s more grotesque standards. Likewise with Bugs’ plea of “Even the Government turned me down!”, outfitted in Decoy to reflect the War as Daffy displays his rejected draft card.

The poor, sick rabbit bit is used next as Pinto Colvig’s coughs from Porky and Teabiscuit are reused to supply Bugs’ own malaise. Though far from the solid, meticulous theatrics of his fake-out death in A Wild Hare, his pity party is MUCH more convincing and much more reliant on pathos than the display seen in Porky’s Hare Hunt, where he wheezes for a few seconds before marching—perfectly well—away.

Cut to a close-up of a tearful Sourpuss, whose animation is wholly unappealing. Perhaps his personality owes a bit to this; though Elmer isn’t exactly a very endearing character himself, he’s enough of a hapless sap to make the audience feel bad for him, especially when he bursts into tears upon Bugs’ fake-out death in A Wild Hare. Much of it has to do with how convincing Bugs’ performance was, but Elmer’s gullibility and helplessness (it is very obvious that his big bad hunter display is a very transparent act) plays a big role in that as well. Though the performance of proto-Bugs here isn’t as convincing, it is at least solid in its intent for pathos; one finds it difficult to feel bad for Sourpuss as he’s reduced to tears. With how nasty, abrasive, and otherwise bland he is, there is little there to spark sympathy.

Nevertheless, close-up paintings continue as Bugs now pulls out a joy buzzer to “shake an’ forget the whole thing.”

Enter the inevitable. Though the shooting of the animation on twos reduces and stiffens the freneticism of the shock, Treg Brown’s metallic cranking/reeling sound effects are delightfully creative and unconventional but in a way that still fits the action.

Hardaway manages to cheat the next scene; the camera pans right to account for Sourpuss flopping onto the ground, with Bugs completely out of sight. With that, the camera cuts to a rear view shot of Sourpuss facing the now empty road. His “Come back here!” cements any suspicions that Bugs made a mad dash for it in the meantime. Admittedly, the cut is slightly disarming when noticed, but certainly economical. A longer pause before cutting or perhaps a quick “whoosh” sound effect from off-screen would do better at suspending the illusion.

Nevertheless, the history of Hare-um Scare-um continues to grow more fascinating by the second; for years, the ending of the cartoon was considered lost. In the cut version, Sourpuss yells “COME BACK HERE AND FIGHT LIKE A MAN! I kin whip you an’ your WHOLE family”, prompting an army of identical Bugs’ to swarm the scene, dukes up and all. At that point, the scene would fade to black and end the cartoon.

We, however, are fortunate enough to view the uncut ending. Bugs’ family actually does manage to “whip” Sourpuss, action obscured through an anticlimactic puff of smoke and conveyed purely through sound effects.

A gun is heard firing off-screen not once, but twice…

…and the real Bugs zips back into frame, greeting Sourpuss with the broken remains of his rifle. Gil Turner’s drawings of Sourpuss look awfully reminiscent of Egghead, particularly when he looks down at the gun as Bugs lectured him: “Y’oughta get that fixed! Somebody’s li’ble to get hurt!”

The audience is greeted with one last chorus of proto-Bugs laughter as he mechanically bounces on his head and out of view.

As it turns out, comparisons of Sourpuss to Egghead are not completely unfounded; Ben Hardaway borrows from his own writing in a direct steal from Daffy Duck in Egghead. Like Egghead, Sourpuss snaps from the madness of it all and engages in his own hysterical, head bouncing, hurr hurr-ing exit.

Ironically enough, this is an instance where the cut ending is better than the real ending. Removing the true ending scene for violence seems unlikely, and may have been because of its staunch similarities to Daffy Duck and Egghead, but who’s to say. Ending with the “whole family” punchline is short, sweet, and to the point—the rest feels excessive and mechanical, again antithetical to what made the success of Daffy so great; his spontaneity. He did not feel like a pale imitation of his predecessors—he was the first of his kind. Hardaway’s Bugs, however, owes his entire existence to being an imitation. And, as an imitation, it isn’t surprising that he isn’t as good as the real thing.

Thankfully, as has been mentioned countless times before, Tex Avery would swoop in and save the day, giving the rabbit a total makeover and someone worthy of appeal, charisma, and actual personality. With that said, the transformation between Rabbit A (Hardaway’s rabbit) and Rabbit B (Tex’s rabbit) isn’t as cut and dry as one may think.

As this cartoon essentially proves, Hardaway’s rabbit lays out somewhat of a blueprint for the vestiges of his refined self. The cross dressing, the disguises, the sad sack routine, the smug control; Hardaway’s rabbit is infinitely more crude and less sophisticated in his approach, and saying “Ben Hardaway was THE person to invent Bugs doing drag, THE person to invent Bugs in a disguise,” and so forth feels far fetched. After all, Jones’ proto-Bugs in Prest-O Change-O had his own display of smugness and effeminate tendencies that could be likened to his future self. Still, much like the difference between the more screwy Daffy and more grounded Daffy, the progression isn’t nearly as black and white as one may think—more so, it is a series of refinements and building off of preexisting traits or experiments with the characters.

As a whole, Hare-um Scare-um fares better than a number of other shorts in the Hardaway and Dalton catalog, and is a vast improvement from Porky's Hare Hunt. With that said, much of the praise is due to understanding Bugs’ progression and impact as a character. This short is much more important for historical reasons than it ever is for entertainment purposes—it isn’t awful, and there are a number of highlights (the drag sequence, the song number) that are genuinely fun. However, it is still nevertheless littered with Hardaway’s bad habits—awkward direction, a complete disregard of subtlety, over reliance on certain gags or quirks, unrealized vocal direction, iffy animation at times, and so forth. Regardless, it is undoubtedly an important piece of filmmaking. Not exactly for the content itself, but for what it stands for in the roadmap towards Bugs Bunny’s development.

.gif)

worth noting the yellow gloves make another appearance on fully-formed bugs in "rhapsody rabbit"

ReplyDelete