Disclaimer: This short contains racist stereotypes and caricatures, presented wholly for historical and informational context. I encourage you to speak up and correct me should I say something ignorant or harmful--it is never my intent to do so and I wish to take accountability, should that occur. Thank you.

Release Date: September 23rd, 1939

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Tex Avery

Story: Tubby Millar

Animation: Chuck McKimson

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Robert C. Bruce (Narrator), Mel Blanc (Ferry, Inuk, Dogs), Dorothy Lloyd (Hen), Tex Avery (Timber Wolf), The Rhythmettes, The Sportsmen Quartet (Chorus)

(You may view the cartoon here for yourself.)

A new cartoon season demands new opening titles. Land of the Midnight Fun is the first cartoon to debut the oddly but nevertheless proudly patriotic red, white and blue concentric rings with painted clouds in the background; eventually, the rings as a whole would grow more opaque for a brief period of time from mid-late 1940, clouds excised. Not much discussion in these reviews has been delegated exclusively to the changes in the opening titles (which are oddly frequent, whether through grand makeovers such as these or as subtle as removing a phrase)—menial as it may be to pick up on, it is still certainly a part of the history. The cloud background in particular has always been anomalous in itself, which begs at least some sort of acknowledgement.

Likewise, the animation credit attributed to Charles “Chuck” McKimson also deserves some sort of acknowledgment. One of the three McKimson brothers, Chuck would later animate under his brother Bob’s direction after briefly leaving the studio to fight in the war. He stayed there until the studio’s closure in 1953, where he would then move to Dell Publishing to pursue a career in comics as an art director, much like his brother Tom.

|

| From left to right: Bob, Tom, and Chuck McKimson. |

Land of the Midnight Fun is somewhat of an anomaly for Avery. For one, it may be one of his most visually complex cartoons during his Warner tenure to date—animated opening titles of the credits sliding in through a pseudo multi-plane camera pan duly note as such. Likewise, it is relatively straightforward, pertaining only to one set location with no meandering side plots. Moreover--albeit bogged down today through Inuit stereotypes and caricatures--from a technical standpoint it is one of Avery’s more confident and thusly funny travelogue cartoons. A boldness presides in certain deliveries that appears to be missing in other analogous travelogues.

Even through the short’s opening are such strides and improvements visible. Much of the exposition parallels the opening to The Isle of Pingo Pongo, Avery’s first venture with the structure; having learned the art of chewing the scenery, Avery’s opening for Midnight Fun savors the natural environment in which he is parodying—Robert C. Bruce’s calm orations and various establishing shots of a cruise liner deceptively lull the audience into thinking they are about to receive the “educational cruise” promised by the narration.

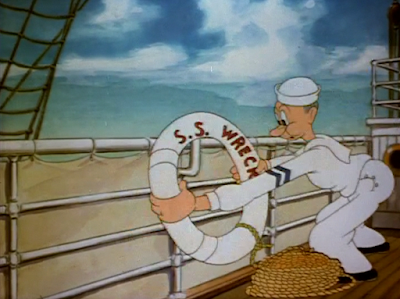

Revealing the name of the ship to be the “S.S. WRECKS” immediately discards such assumptions.

To compare, Pingo Pongo’s exposition was much more abrupt, opening only to the smokestack of a ship (“HALF DOLLAR LINES” and whistles blown to “Shave and a Haircut” asserting the cartoon’s own lighthearted tone); while the abruptness is nice in itself, Avery’s false sense of security with Midnight creates a greater contrast with the tonal whiplash. Thus, more rewarding payoff.

Whistle gags have been elevated from “Shave and a Haircut” to actual speech—not unlike the maneuvers later executed for Disney’s Dumbo, the “aaaaaall abooooaaard” was spoken with a microphone placed on the speaker's throat before being run through filters to render the sound more mechanical.

And, of course, the exit of the ship itself has further been elevated. Whereas Avery’s focus in Pingo was related to the environments more than the ship itself (more “DOLLAR AND A HALF LINES” signage, traffic intersection gags), Midnight gets right to the source. Animation of an anchor lifting and thusly scrunching up the bow of the ship precedes the sort of stylization Avery would heavily embrace later on in his career—the flat staging of the boat in profile allows for the visual to read with a certain mischievous clarity that may otherwise be lacking had they approached it from a 3/4 angle instead. Absolutely no acknowledgment from the narrator on the abnormality render the sequence a success.

“And we’re on our way!”

Another no nonsense delivery in which the ship executes a three-point turn (car engine sound effects serving as a fine topper and great way to further comparisons) and shoves off deserves credit; much more stimulating and visually impressive than the horizontal staging of a painted boat overlay passing through. Likewise, more playful.

Painted overlays are reserved for the next sequence, posing more as a compositional frame rather than an animation device in itself. An overlay of the ship’s rail provides both a point-of-view shot for the audience an a visual frame for an oncoming ferry—mildly homophobic fairy/ferry wordplay ensues as effeminate “woo woo!”s from Blanc serve as the boat’s whistle.

The next sequence of the ship physically hugging the coastline (in accordance to Bruce’s narration) is a direct grab from Pingo Pongo. Pingo placed a heavier emphasis on the map, demonstrating a not-so-direct course, whereas Avery literally embraces the distortions brought on by the ship snaking past the coast—something demonstrated only fleetingly in the aforementioned cartoon.

Unsurprisingly, Avery’s revisions on the similar gag pay dividends. Not only is the animation itself more refined, its staging placing a heavier emphasis on the coast’s curves rather than the boat curving itself in the former, but Carl Stalling’s music score—as always—further carries the gag. Following an ongoing motif of “Song of the Marines”, Stalling briefly distorts it to reflect the actions of the ship through a slurred, circuitous rhythm, but is able to keep it recognizable and true to the musical foundation so that hardly a beat is skipped when it melts back into its unaltered rhythm. A great way to score the music to the action but maintain the melody at the same time.

Artistic grandeur reaches new heights for Avery in the next shot of the ship traversing the waters. Here, the painted overlay of the ship actively ties the composition together rather than appearing as a trick to seem more striking than it actually is—the 3/4 perspective of the ship, the collaboration between the ship’s lighting/overall painting and equally gorgeous sunset, the rhythm of the ocean and its own bold hues, as well as the gentle rocking of the camera as a whole all meld particularly well together, which each contributing aspect pulling its own weight. Though the scene exists only as a means of showing off, it is well earned—Avery and company could have only ever dreamed of reaching such merit only a handful of years prior.

A somewhat abrupt cut is made to focus on the waters of the ocean itself—from the aquatic focus to the visual distortions provided through the use of ripple glass (used in outings such as Disney’s Pinocchio or The Old Mill, again furthering Disneyesque connotations), the following sequence precedes the motifs and overall theme touted in Avery’s next film, Fresh Fish.

Described by Bruce as “a fisherman’s paradise”, the audience is again lulled into an effective false sense of security through a rather straightforward but nevertheless solid and sophisticated introduction to the various fish inhabiting the waters: barracuda, swordfish, tuna…

A half canned/half living salmon hybrid strikes Avery’s itch to purposefully rise a groan from the audience. Juxtaposition between the sculpted, deceptively domestic and overall elaborate set-up of the fish animation/underwater effects and the corny payoff serves as a joke in itself—the execution and build-up is truly what sells it rather than the joke itself.

Transitions and overall pacing between scenes was still something Avery was trying to perfect, and a jump cut from corny fish puns to a much more panicked tone comes as almost a little too jarring. Such an abrupt cut certainly compliments the narrator’s panic at discovering a man shipwrecked and urging a nearby sailor to throw him to safety, but the tonal contrast between the two adjoining scenes is so stark that something like a cross dissolve would help in easing the flow more efficiently.

Nevertheless, viewing priorities lie towards saving the shipwreckee. Avery’s speed and sends of timing continues to grow sharper as the years go on—the briskness in which the ship brakes to a halt like a car again feels like something out of one of his MGM cartoons. The life ring being tossed out from the boat instead of cutting to a new shot of the sailor throwing it himself preserves the urgency and overall momentum of the scene; Avery understood that it was vital to maintain the audience’s interest through particularly panicked sequences. To waste a shipwreck rescue through leisurely pacing and cutting would be disastrous.

Of course, the rescue is never as big of a priority as the build-up. In pure Avery fashion, the man overboard throws the life ring off-screen with hearty disdain. No explanation given. Likewise, no explanation needed; Avery has the viewer in his clutches now. They know a payoff is coming and to trivialize that with meandering dialogue would be criminal.

Said payoff is pretty raunchy for 1939 Warner's—hoisting a woman up in his arms, it is revealed the barrel on the raft was a strategic blockade to conceal their implied kissing and lovemaking. Stalling’s lovelorn music sting of “Heaven Can Wait”, the incongruity between the woman’s tattered clothes and her perfectly intact nylons/heels, and overall control of the sequence by fading out to black instead of squeezing any gobsmacked dialogue from the narrator. In fact, just before the camera drops to complete black, they start to make a move to kiss yet again. Bold, clear, and simple storytelling.

Segueing from one tone to another grows smoother in the next transition as Bruce makes comments about the seas being “a bit choppy.” Instant rebuttals are carried through the visuals as the ship nearly capsizes, turning on its side as it is violently thrashed about. Praises again must be sung for Avery’s restraint—to score the contradiction with an ironic, jovial music sting would be a less confident approach. Stalling’s orchestrations of “The Storm” convey more urgency and dramatics that suspend the audience’s belief with the deliberately ridiculous visuals—such confidence is refreshing.

Bruce’s apt comments about passengers making the trip by rail (as demonstrated through said passengers implied to be puking over the side of the boat) would be reprised briefly in Bob Clampett’s Pilgrim Porky a year later.

Clampett’s example, though used in an equally jaunty song number, possesses the self awareness that makes Avery’s restraint here all the more commendable. Calling less attention to the sickness of the passengers through the narrator’s dismissive, quaint orations allows for the flow to move more freely—less spelled out than freezing a song number that already freezes the cartoon in itself. Both approaches have their respective merits for their respective environments, but Avery’s control exercised here fits particularly well for the free flowing momentum of his short. Self aggrandizing or pregnant pauses are sparse.

Further commendable is how promptly Avery switches from one gag to another. To Avery, lingering on more storm gags would grow excessive—the audience has been able to digest the roughness of the excursion. Instead of demonstrating the waves subsiding or the clouds parting, a transition is merely indicated through Bruce’s narration: “Later, giant icebergs begin to make their appearance.” No “the storm has finally lifted” or any sort of acknowledgment that follows. For Avery’s purpose in cramming as many gags as possible in a short amount of time, trying not to overstay each welcome, it pays off considerably.

“LOS ANGELES CITY LIMITS” gags would pepper the shorts for years to come—it, too, makes a return from The Isle of Pingo Pongo. Likewise with the verbiage of Good Humor ice cream now being dubbed as “Good Rumors”—much like the various spins on First National Bank (Worst, Second, Last, etc.), its wordplay would prove evergreen for directors looking to sneak in an easy pun. The exuberance of the ice cream man and lack of commentary (from the narrator himself or reflected in the filmmaking) prove a successful combination.

Robert C. Bruce continues to enlighten the audience, introducing them now to the icebreaker ships carving pathways through the frozen waters. “Let’s see how it’s done.”

Designating a peephole in the bow of the ship for said icebreaker (manually carving away at the ice with a pick) almost grounds the gag and adds a certain level of humanity—seeing the human arm is amusing in itself, but going so far as to add an eyehole even outside of its functionality assures the audience that there is a real live human being doing all the work, naturally eliciting a collective “poor ol’ guy” response from the viewer. Avery’s humanization of the gag applies in numerous ways.

Visual merit continues to be upheld through strategic establishing shots as the cartoon finally arrives at its destination; the ripple glass effect on the water combined with the static, non-moving landmasses makes for a discrepancy that betters the overall picturesqueness rather than harms it. Such a technique was first employed in Ben Hardaway and Cal Dalton’s Porky the Gob.

Honing in on the sign welcoming the viewer to Nome, Alaska (complete with the “THERE’S NO PLACE LIKE NOME” tagline) feels reminiscent to similar variations in Avery’s MGM works—The Shooting of Dan McGoo’s setting of Coldernell, Alaska combines both in one.

Animation of the ship parallel parking into the docks is not only an amusing visual, but a satisfying parallel and bookend to the ship’s three-point turn exit at the beginning. Both gags are made stronger and more humorous for the connection alone.

Execution and brisk, no nonsense delivery of the next sequence demonstrating the process of the ship docking is, again, a mark of its triumph. The anchor dropping into the sea with no chain attached and passengers descending the gang-plank right into the waters are truthful to the narration—such a sharp sense of routine and lack of questioning render it confident and funny rather than routine. Trampling sound effects as the passengers rush down the gang-plank (and the speed in which they rush) are particular points of note.

A fade out and back in cements the start of the cartoon’s second act. Negative Inuit stereotypes and caricatures are regrettably abound, as is derogatory language as a whole—to deem such racism as “disappointing” is trivializing, but it is disappointing that such sharp timing and execution in a general sense must be delegated to such imagery.

Nevertheless, clever staging prevails during one sequence dedicated to observing an Inuk frying a fish in his igloo. Clarity and simplicity is Avery’s foremost focus. As such, when the man crawls inside his igloo and the camera dissolves to view the interior, the entryway of igloo (and much of its bottom as a whole) fade away completely. To keep them there likely would have posed a visual obstacle and obstructed the view of the cramped fish fry—Avery did not want to distract his audience from the joke at any costs.

“Chickens are not rare in Alaska.” Incongruous set design of troughs, buckets of feed and chicken wire fencing frozen over provide a creative connection to the same material seen “at home”. Avery uses such an establishing shot as a means of transition, particularly to the inside of an igloo…

Mama hen’s frigid “Gee, it’s co-o-o-o-o-old!” sounds nearly identical to the exact same line in Chicken Jitters. Likewise, the “br-r-r-r-r” sound effects were used verbatim from the ever-recent Si*ux Me.

As is the punchline. Outside of a somewhat unnecessary camera truck-in towards the nest revealing her frozen eggs, Avery’s approach is much more direct and “businesslike” than Hardaway and Dalton’s—no quizzical stares from mother hen or the ironic trumpet sting heard in the former. Avery could often get slightly overzealous with his camera pans, bringing more attention to a gag than what was really necessary, but not often enough to be actively detrimental.

“Here’s a little duck who forgot to fly south.”

Said duck possibly sheds a brief glimpse as to what Daffy would have looked like in Avery’s cartoons from 1939 onward. The contrarian nature in which it defies the narrator’s comments foreshadows a similar interaction in Avery’s Wacky Wildlife—here, the payoff is much more amusing as the duck waddles off with its frozen waistline. Its exit being pure pompous offense rather than a gratuitous exit like the mother hen makes the punchline hit harder—some of the most well sculpted ice animation to date helps with that too.

Cartoons centered around Inuit stereotypes almost always include an appropriate of kunik (better known as an “Esk*mo kiss”): serving more as an affectionate greeting between family, it generally involves gently placing the tip of one’s nose against one’s nose, cheek, or forehead.

General misinformation and perpetuating of stereotypes aside, Avery’s execution of the gag is certainly strong, whether it be the woman rubbing lipstick on her nose, grotesquely aggressive rubber squeaking noises as they rub noses, or the sheer, red-hot ecstasy of the boyfriend as he practically convulses in place, unable to keep his lust inside…

“WOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOW!!”

Blanc’s histrionics and the pure zeal of the movement, camera movements, and filmmaking overall are a brilliant contrast to the coquettish music score and set-up as a whole. An extra melodramatic pump of the legs before the man collapses for good is a plus. Its energy is certainly potent.

Moreover, another installment in Avery’s “dogs peeing on poles and/or trees” saga proves difficult to dismiss in merit. In fact, its simple but purposefully strategic staging is, again, a joke in itself—the pregnant pause as a dogsled team comes to a halt, any action obscured by conveniently arranged chunks of ice, and curt resuming of activities is gorgeously matter of fact. That the audience immediately understands the joke with no quirky rip offs from the narrator or even dogs themselves speaks to Avery’s clarity, boldness, and confidence as a director. No need to spell it out for the viewer. Avery trusts us to get the gist.

Sticking to the canine theme, the narrator then introduces the audience to the Alaskan timber wolf. Vocals provided by Avery himself, the sheer, unadulterated sincerity in his laughter as he points at the lone tree and repeatedly shouts “TIMBERRRRR!”, only to be interrupted by an oncoming fit of laughter is priceless. His laughter in just about every single instance of its appearance always maintains such a miraculously potent joy and genuineness that, no matter the context or gag, is always such a delight for the ears.

Capitalizing on the delightful stupidity of the gag, Avery graces the audience with his signature self-aware commentary as the camera cuts into the wolf. The confidentiality of his “Gee, this is silly” concession to the audience is always a plus—the brief intimacy seems to bring the viewer even closer to Avery’s filmmaking in that moment. (That he himself is providing the vocals may play a part in this as well.)

In spite of said silliness, the antics resume with only the fading out of a camera to quell his cries. The sheer delight in Avery’s vocals pardon the self aware commentary—while said interruptions and commentary can absolutely be a source of brilliance, used too often or too close together they can sometimes read as a crutch or seem too self deprecating to appreciate. Joyful filmmaking and execution as a whole is necessary for the contrast to really hit hard, and here it does just that.

The next sequence of a penguin gobbling up some fish takes the mantra that “comedy comes in threes” to heart. First two dives into some areas of exposed water are executed normally enough, swift enough to keep the pace but clear enough to establish a solid pattern.

A fish emerging from the third puddle isn’t new by any means, and has been a classic gag since the days of Harman and Ising, but Stalling’s musical accompaniment of “Strolling Through the Park” (which makes its grand Warner cartoon debut in this moment) and strategic musical emphases elevate it beyond the surface level.

Comparisons to Avery’s The Penguin Parade begin with the design of the penguin itself and are furthered through the next spotlight: an arctic nightclub. Considerably more sophisticated (in terms of design, that is; though pretty juvenile, the Brass Monkey naming convention is a great double-meaning and wonderful tease with the censors—not only is it used as a crude means of measurement, hence “cold enough to freeze the balls off a brass monkey”, it doubles as a cocktail consisting of vodka, rum, and orange juice) than its penguin predecessor, Avery’s growth as a director and designer continue to grow more marked. No happy-go-lucky penguins waving rainbow spotlights here.

In fact, one could make the argument that the coming scene is almost TOO sophisticated and not lighthearted enough. In a rare moment of sheer, unadulterated saccharinity and earnest, a musical chorus of “The Kiss Waltz” is sung over rotoscoped animation of an Inuit ice skater—general execution and mannerisms not unreminiscent of Norwegian Olympic skater Sonja Henie, who, in 1939, had already starred in 4 Hollywood films in just 2 years.

For what the 1939 Avery stood for, the scene comes as a genuine surprise; choruses in his cartoons have been used sparingly, unless a pure point of parody (such as the number in A Feud There Was.) Even then, various antics and jabs at comedy would be interspersed throughout the songs to maintain the audience’s attention. Very rarely, if ever, have such Disneyesque attitudes been wholeheartedly embraced. It absolutely is a means to fill time.

With that said, it is certainly effective in its goal. While some of the inking on the animation does occasionally delve into the cruder side (particularly upon a close-up of a brief panty shot, which are plentiful,), the animation is gorgeous, solid, and incredibly impressive for 1939 Warner standards. Such intricacies and, admittedly, steel focus on sex value hint towards the performances touted in shorts such as Red Hot Riding Hood.

Avery’s simple staging works well as a stylistic choice—the pure black background covers the entire sequence in an ethereal sheen; it was certainly made with live action filmmaking in mind. Focus is isolated purely on the skater. The audience has no choice BUT to admire the animation. That, too, is a decision that requires a lot of confidence and trust in both the audience and the animators themselves.

The conclusion of her number segues into the third of the act: going home. Abrupt to an almost comedic degree (a sequence where a cross dissolve or fade rather than straight jump cut may have helped to ease the transition), the narrator’s plucky comments about it being late—“Half past October? We must leave!—“ and coinciding visuals of a month-themed clock face with mittens on it seem to represent Avery’s relief at going back to doing things his way.

Much like the connection between the ship’s exit and entrance to Alaska, Avery’s reprisal of the “aaaall abooooard” whistle gag, passengers scaling the gang-plank (emerging yet again from beneath the water!), and anchor magically levitating into place tie the cartoon in a satisfying bookend that renders the entire travelogue coherent, tidy, secure. While the parallel structure may seem like rather obvious and deliberate choices, much of Avery’s magic as a filmmaker comes from being obvious and deliberate. So few of his spot gag cartoons share the same confidence and organization seen here.

A good portion of the short’s final is dedicated to scenery chewing, but Avery has absolutely earned the right to do so. Johnny Johnsen’s paintings are stunning, vibrant, cozy and warm but not to a degree that feels excessive. Familiar is a more fitting word.

Comparing the shots of the ship silhouetted against the arctic sunset to the similarly structured closing pan in The Isle of Pingo Pongo—both accompanied musically with a similarly contented arrangement of “Aloha Oe”—exposes a director who has vastly grown in artistic expertise in just the matter of a year. Backgrounds feel more solid, controlled, tight, not rubbery or accidentally synthetic.

Likewise, even though the tone marks another shift as the narrator notes an impending heavy fog, the art direction does not. An aerial shot of the painted ship parting through the waves is no less impressive than the similar, earlier shots of it taking off on its voyage.

Confidence continues to manifest through even the most menial of details. If he truly wanted to, Avery could have had the fog completely enshroud the screen. While that in itself is true, the lights of the ship remain visible. The audience is not left deserted and to fend for themselves, an impending punchline or means of transition isn’t immediately obvious; while the fog does absolutely serve as a means from point A to point B, it is executed in a way that prioritizes the cinematography first and foremost. It does not at all feel like a cheap trick to pull the wool over one’s eyes before revealing a punchline.

Said punchline is classic Avery, but works incredibly well with the context and climactic build-up. From the narrator’s commentary, the frightened music stings, and staging/animation as a whole, such a purely silly payoff comes as such a strong whiplash that the laughs are garnered through its execution more than the visual itself.

From its confidence to its coherency, Land of the Midnight Fun is easily one of Avery’s best ventures in the spot-gag format. While the racism stemming from derogatory Inuit stereotypes absolutely should not be trivialized (and very much does serve as a detriment), speaking purely from a filmmaking perspective, Avery exudes a level of self-assurance so painfully lacking in much of his other works.

Simplicity = boldness. This short in particular is a fantastic demonstration of the aforementioned phrase. Distracted not is Avery by meandering side plots or the threat of having to encompass multiple settings in one cartoon. Even some of the weaker gags purposefully meant to endure eye rolls and groans are delivered with a certain energy and wry spark that render them more sympathetic. Parallels are adhered to strongly for the overall digestibility and clarity of the picture, which makes the audience feel as though they’ve spent their time well. There is a definitive start and end—no “that’s it?” or looming, quizzical emptiness that other travelogues are often subject to.

General ignorance, racism and overall misinformation do ground the short back to reality. Igloos are not common to Alaska (nor are they a common means of housing), nor do Inuks vigorously rub noses together for romantic intent. Moreover, a general smattering of other stereotypes such as certain exaggerated physical features, traveling only through kayaks or dogsleds, wearing only parkas, etc. continue to perpetuate inaccurate and negative stereotypes, which is a feature sadly common with Hollywood cartoons of the golden age exploring different regions of the world.

Nevertheless, unfortunate as it is that such rare strength all around must be attributed to such negative aspects, Land of the Midnight Fun is a refreshing anomaly for Avery’s style of filmmaking. Concise. Simple. Funny. Playful. Visually attractive. It’s rare for Avery’s spot-gag cartoons to strike so many of these aspects at once. Slowly but surely, Avery continues to build a foundation for the elements found in his MGM cartoons.

No comments:

Post a Comment