Release Date: September 23rd, 1939

Series: Looney Tunes

Director: Bob Clampett

Story: Ernest Gee

Animation: Vive Risto

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Porky, Ghost, Cop), Pinto Colvig (Engine)

(You may view the short for yourself here!) Jeepers Creepers serves as the last story credit for Clampett’s high school buddy and collaborator Ernest “Flash” Gee. Interestingly enough, Clampett admitted Gee contributed to about 3/4 of the entire story for Bugs Bunny Gets the Boid (in spite of Warren Foster getting the credit for that short) in an interview with Michael Barrier. According to Clampett, Gee was best at pitching ideas on the fly rather than sitting down and putting them on paper. Indeed, the filmmaking and overall story of Jeepers—even if it itself is far from Clampett’s best—seems to feel much more inspired than the insipid Porky’s Hotel.

Jeepers Creepers serves as the last story credit for Clampett’s high school buddy and collaborator Ernest “Flash” Gee. Interestingly enough, Clampett admitted Gee contributed to about 3/4 of the entire story for Bugs Bunny Gets the Boid (in spite of Warren Foster getting the credit for that short) in an interview with Michael Barrier. According to Clampett, Gee was best at pitching ideas on the fly rather than sitting down and putting them on paper. Indeed, the filmmaking and overall story of Jeepers—even if it itself is far from Clampett’s best—seems to feel much more inspired than the insipid Porky’s Hotel.

An unofficial response to Disney’s 1937 hit Lonesome Ghosts (whose influence can be felt through a number of gags in this cartoon), Clampett experiments with the age old haunted house set-up. Upon instruction from the chief of police, officer Porky is sent to investigate strange noises coming from an abandoned house, prompting a screwball ghost to have some fun with his new, nervy victim.

Similar to the opening of Porky’s Hotel, an aerial shot of a sleepy, rural town attempts to establish the overall tone of the setting. Dick Thomas’ penchant for strong contrast in his lighting and value elevate a shot that is serviceable to pleasing.

Unlike the opening of Porky’s Hotel, however, such seemingly saccharine and domestic environments are somewhat of a farce—a camera truck-in to Podunk City Jail, complete with obligatory punny signage (perhaps the most amusing detail of the shot being a “vacancy” sign lazily hung next to a window whose bars have been welded open rather than the verbiage) indicates a more witty, comparatively tongue-in-cheek approach than the directness seen in the former cartoon.

A silhouette of a police chief calling “Car 6 and 7/8ths” over the radio owes much of its limited design to Tex Avery’s The Blow Out. To Clampett’s credit, he didn’t reuse the animation verbatim and slap a silhouette over it as he did of the same officer in Porky’s Movie Mystery—here, he merely speaks into a microphone (sans headphones), but his general, bulbous construction do give away the source to keen eyes.

“Kop’s Kar” plastered on the side of officer Porky’s car not only trivializes his authority as a whole (purposefully dinky, putt-putt design of the automobile further asserting as such), but serves as an additional nod to Mack Sennett’s Keystone Kops. Through the silent comedy connections, unorthodox numbering and purposefully pitiful disposition overall, such a set-up purposefully betrays the foreboding, stolid exposition of the cartoon.

The same could be said for the car squealing to a halt with rubber tire feet. Porky’s blank stare at the camera and dubious “Weh-weh-why, that’s me!” upon being called on the radio purposefully do little to incite confidence as well—the juxtaposition between the dour prison, warnings of mysterious noises coming from a deserted house and cute, soft, happy-go-lucky nature of Porky on a nighttime drive is solid. Judging by the smaller eyes, slightly unorthodox mouth shapes, pronouncedly curved ears and general stylization of the second screenshot below, it's quite possible that this is Norm McCabe's animation.

John Carey beautifully animates a close-up of Porky listening to the radio; his tendency to animate slow, pregnant blinks helps to sustain Porky’s calculating pause and convey innocent impressionability as he clings to the words of the police chief.

While Blanc’s delivery of “Deh-deeah-deh-dee-did he say geh-eh-gih-gee-eh-ghosts?” feels somewhat static and by-the-books in response to the police chief’s warnings, it serves more as a vehicle for incoming jokes rather than insight into Porky’s personality—Carey follows those duties through his careful, trepidatious but curious reactions to the radio broadcast.

“Yes, ghosts!” Clampett subscribes to Tex Avery’s theory of double-sided radio transmitters as the police chief belittles Porky’s queries.

“You know, those white things that go MUAHAHAHAHAHAHA!” Blanc’s joyously sinister deliveries and Carey’s expertise for elastic, particularly motion-oriented animation prove to be a winning combination as Porky is thoroughly startled from the commotion.

Nevertheless, duty calls, and Porky prepares by gearing his cruiser up to full throttle. Treg Brown’s boisterous engine revving sounds add an aggression exuberantly incongruous with Porky’s vacant, smiling expression; more Podunk, faltering engine revs heard in Porky and Teabiscuit from Pinto Colvig are more true to the overall dinky disposition of the role. Both feed well into Clampett’s playful first-and-foremost vision.

Especially given the pay-off: maintaining the anthropomorphic tire theme from before, Porky creeps along the country road with his car as quietly as possible. Sharp timing, excessive build-up, and overall delivery embolden the contrast and make it a success. No matter how admittedly juvenile or just plain stupid the gag may be, the type of embrace it receives here (even going so far as to add eyes to the headlights of the car, further humanization sustaining the overall whimsy) that was so lacking in Porky’s Hotel is a refreshing change of pace.

Even then, Clampett’s trigger finger reliance on eliciting laughs from the audience continues to manifest through often unnecessary puns or signage. The “Belli Acres”/bellyachers wordplay gets somewhat of a pass, as the sign is a smaller part of an entire composition and not the exact focus. Rather, attention is delegated to the ambience.

Haunted houses almost always require heavy storms and howling winds. Through the combination of Dick Thomas’ gorgeous backgrounds, Carl Stalling’s interspersing his threatening music score with little stings that accompany the action well (such as alarmed, brass chords every time lightning strikes) and relatively rhythmic pacing as a whole make the clichés intriguing and serviceable rather than detrimental.

Clampett’s playful humor helps in bestowing the sequence its own identity. While some attempts at mischief are more groan-inducing than others (such as window shutters knocking “Shave and a Haircut” on the side of the abandoned house, interest stemming more from its direct nod to similar maneuvers in Lonesome Ghosts), others are more inspired.

A bolt of lightning striking a rooster shaped weathervane and turning it into a smoldering, wholly roasted chicken is incredibly dumb. However, said dumbness is wholeheartedly embraced rather than shunned. It doesn’t try to be something it’s not. It makes no sense, it isn’t supposed to make any sense, and Clampett thankfully lets it relish in its stupidity through straightforward, non-attention seeming filmmaking and moving swiftly to the next piece of business.

Next piece of business is yet another direct homage to Disney’s Lonesome Ghosts as the camera pans through the interior of the household. Whereas Lonesome’s pan is quick and leisurely, a tour of the mansion held only briefly before focusing on the eponymous spirits, Clampett’s camera pan is frenetic, wild, a panicked catharsis that echoes the equally crazed ambient laughter heard in the household. Rapid truck-ins, truck-outs, and curt slides back and forth seem to mimic both a lost bystander caught in the terrors of the house and the point of view of a ghost thrilled to explore his new digs. Disney’s pan is more picturesque. Clampett’s is more fun.

Even then, the crazed laughter is all hit a decoy—a truck-in and cross dissolve to another room reveals the source of noise to be a radio. After the exceedingly aggressive clamor dies down, a soft spoken radio announcer bids his audience farewell—the “Sleep tight, kiddies!” in itself serves as a wry contrast to the almost violent hysterics heard from the program itself.

Instead of structuring the cartoon around attempts to trick the viewer or characters of ghosts lurking nearby, Clampett gets a taste of both alternatives. Such crazed, manic laughter leads the audience to believe that the house is inhabited with a frenzy of aggressive ghosts. Revealing the radio assures them that it’s all just a gag, ghosts aren’t real, much of the set-up will focus on tricking the audience or a hapless Porky into believing ghosts inhabit the building.

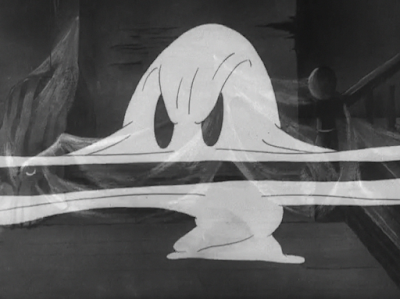

Wrong. Instead, a ghost whose design is full of Clampett’s earmarks (particularly from the simple, streamlined, newspaper comic sensibilities—compare the deliberate amount of caricature and simplicity here to the ghosts in Lonesome Ghosts or even Chuck Jones’ Ghost Wanted from not even a year later) happens to serve as the sentient audience to the program, chuffing contentedly on a cigar in his cobweb covered armchair.

“Gawsh! That was sure a scary sto-ry!”

Curiously, whether due to unavailability or budgetary constraints, Mel Blanc voices the ghost doing a Pinto Colvig impression rather than Colvig himself supplying the vocals—somewhat ironic given the reused car engine sound effects provided by Colvig.

Blanc’s interpretation of the shtick is solid enough to likely fool unaware audiences (which, seeing as Blanc never received a voice credit until 1944, was not unfounded), but is undoubtedly his own doing. Part of Blanc’s charm and prowess at doing so many voices is that—no matter how exaggerated or different—listeners accustomed to his acting will always know it’s him providing the voice. That comes as both a great strength and both a slight weakness depending on the demands of the context.

Though the coming gag of a ghost dipping his cigar-induced smoke rings into his coffee is clever, it drags on for far too long to maintain its full merit. In total, the sequence lasts for 35 seconds when it really only needs about 15 at the absolute most—Carl Stalling’s lumbering music score, though playful, does little to render the action thrilling. From the arched eyebrows and delicate hand motions to the overall drawing style of the coffee droplets, it’s likely John Carey was tasked with animating the close-up.

Time nevertheless marches on. From one time filler to the next, Clampett sets his sights on a musical number—given the sheer popularity of Warren and Dubin’s “Jeepers Creepers” at the time, the number is warranted. Kickstarted by an old clock chiming the melody (with some particularly sharp timing as the chimes go from foreboding droning to a quick, jazzy flair), the sequence as a whole is much more inspired, energetic, and akin to Clampett’s sensibilities than what was displayed through the 20 second chorus in Porky’s Hotel.

In fact, Clampett at times verges into territory that is almost too self indulgent (particularly the ghost bursting into a fit of mouth waggling screwball hysterics—not unlike the classic “breakthrough”/hysterical build-up touted by Clampett’s Daffy—or a brief chorus of “A-H(a)unting I Will Go” intersperses with random horse noises), but again, when compared to Porky’s Hotel, it comes as some form of relief.

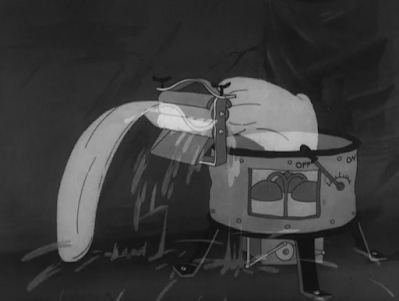

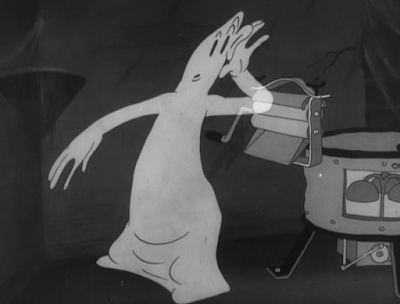

Posing as a whole is appealing and solid—John Carey animates the beginning of the song with the ghost pretending to stalk his victims and engaging in his screwball fit. Gags such as the ghost riding an invisible elevator or taking a bath in a washing machine/sliding himself through the wringer are serviceable and quaint, but provide adequate visual accompaniment when the audience is perhaps more focused on the lyrics (essentially serving as a ballad to the ghost’s motives and orating about how much fun he has haunting other people.)

Its innocent, playful tone make certain self indulgent tendencies or other relatively routine aspects more forgiving—it’s far from Clampett’s most invigorating or engaging number, but it serves its purpose well. It doesn’t immediately scream “time filler” nearly as much as other song numbers—there was clearly a certain amount of attention delegated to it.

Transitions between the song’s end and the next act of the cartoon are somewhat odd when scrutinized—the soundtrack appears to jump somewhat, as though there was something cut in-between. It very well could have just been a housekeeping measure, and it certainly isn’t obvious enough for theatergoers to have caught, but it nevertheless serves as a point of interest.

Upon hearing knocking at the door, the ghost rides the spiral staircase banisters to the ground in a hurry. Purposefully dizzying is the layout to an almost hypnotic degree; rich, dark tones from Dick Thomas’ paintings elevate the whimsical ghastliness of the environments.

Arbitrary as the ghost sliding down the banister, only to slide back up, muse “There’s somebody at the door!” and slide back down again may be, it is brief and the timing is snappy enough to be forgiving. One gets the sense that this short was cathartic for Clampett, as his self indulgent tendencies seem to be particularly concentrated—the joylessness of Porky’s Hotel needed compensation, for both the viewer but Clampett himself in particular.

Such can be seen in the ghost’s response to the frantic knocking. Always a fan of effeminate gags and caricatures, Clampett goes so far as to briefly slap eyelashes and lipstick on the ghost as he coos “Come in!” in a falsetto. The solidity of John Carey’s posing is welcome, especially when compared to the corresponding hook-up pose from another animator.

Further parallels to Lonesome Ghosts are duly established in the ghost’s exit; rather than wrapping himself up like a flapping curtain and disappearing into thin air, he instead transforms into a whirling vortex and shrinks out of sight. Treg Brown’s sound effects do wonders to carry the visuals; the bluntness of Clampett’s approach works well with the overarching tone of the cartoon.

Though his fatigue with the character is not nearly as pronounced as it was in Porky’s Hotel, it still remains evident that Clampett was looking to concentrate more on the ghost than Porky—it takes 5 minutes into the short for their paths to even cross.

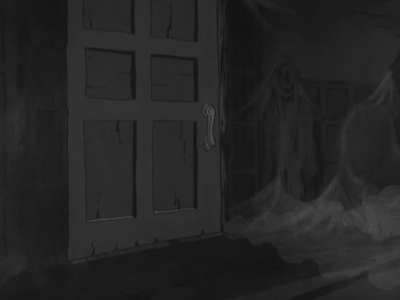

Nevertheless, the suspenseful, anxiety laden build-up is well done as the door slowly creaks open to allow the moonlight in. The raw slowness in which Porky dares to peek his head in reads as more innocent and amusing rather than as an effort to take up time—likewise with the very gradual, slow darts of the pupils. Carl Stalling’s flighty musical accompaniment establishes a tone that is more frisky and playful than truly apprehensive.

Likewise, the voice direction on Porky’s quiet, unnerved delivery of “Is anyeh-buh-be-eh-bih-eh-beh-bih-beh-eh-buh-body… home…?” is considerably more inspired than the norm for Clampett’s Porky of this era. It reads as more natural, emotive rather than the tendency to dip into more broad readings that, at times, feel more like empty announcements.

With no response given, Porky creeps inside the abandoned domicile. Musical accompaniment delegated only to his footsteps sustains the heavy atmosphere; Clampett and Stalling both play well off of the eerie quietude.

That, and serving as an avenue to pull the ol’ “curtains flapping and scares frightened protagonist” trick marked by alarmed music stings. Certainly nothing audiences haven’t seen before, but the speed in which Porky flees—even if the draftsmanship of the animation itself is relatively crude—is welcome.

The peeking through the ajar door routine is repeated again. Though it does come off as a more obvious piece of filler the second time around, it at least serves a functional purpose. Parallels establish rhythm and familiarity, and it does a nice job indicating Porky’s apprehension (as well as poking fun at his credibility.) One wonders why someone who is afraid of curtains flapping has enough gumption to be involved in the police force—sympathy and innocence is prioritized first and foremost.

Having established the routine by now and general set-up, Clampett cuts back to the ghost, who enters a separate wing of the house in the same whirling vortex as before.

As has been mentioned previously, the ghost’s purpose in the story is an odd amalgamation; instead of haunting Porky directly, he creates traps or set-ups that trick Porky into thinking he’s being haunted by something else. Such ensues a rather laborious sequence of the ghost slipping two frogs into a pair of shoes tied together.

While the pacing drags and reads as pedestrian at best, the concept of the set-up is amusing in itself. The ghost just likes to mess with people rather than harboring a vendetta, and said pranking feels more lighthearted rather than actively malicious. Clampett doesn’t hype up the fear factor, the audience doesn’t necessarily root for Porky to make an escape and save his skin. If anything, the audience is led to feel sympathetic towards the happy-go-lucky ghost. Porky just happens to be caught in the crossfire.

Sluggish and tedious as the act grows to be, it at least establishes a steady rhythm—perfect for Clampett to break as Porky turns around and passes the shoes. Carl Stalling’s repeated musical motif carries the sequence completely, maintaining the rhythm and parallel structure. Had it not been so tailor fitted to Porky’s footsteps, one wonders just how much more monotonous the scene would be.

Nevertheless, all is not for naught. With the shoes out of the picture, the ghost takes matters into his own hands by sneaking up behind Porky with a kettle and spoon (not unlike Porky’s rather vicious methods of waking Daffy up in Porky & Daffy.) Viewing the ghost fade in behind Porky deserves praise for the camera team—though there are still occasional gaffes and lapses, the advancements the crew has made with their double exposure effects in just the past year has been nothing short of impressive. Chronic blurriness or clipping issues that were once rampant are now sparse, and the effect as a whole feels much more solid and controlled than before.

Rather than abandoning the shoes completely—which, given the plodding set-up, would have been thoroughly aggravating—they instead reach their purpose by snagging onto a nearby coat hunger. Said coat hanger being dragged into a nearby curtain and thus creating the illusion of a lumbering figure is rather domestic even for Clampett’s standards; the Disney influence seems to be a little too derivative.

That is shortly rectified through thoroughly Clampettesque mild violence as the ghost bangs the pot over Porky’s head and disappears in another vortex. Almost painfully repetitive as the past minute of the cartoon has been, the momentum and pattern it establishes can’t be wholly dismissed. The sequences flow together nicely, back and forth cutting between various walk cycles hinting towards an impending contact.

While the animation of Porky’s head reverberating from the contact isn’t as frenetic as Bobe Cannon’s interpretation in Porky & Daffy (who, is worth noting, has since moved on from the Clampett unit, returning briefly to Tex Avery’s unit before heading over to Chuck Jones) or to similar reverberations seen in Porky’s Naughty Nephew, it’s still very much serviceable. Stalling’s surprised music sting and Brown’s echoing sound effects exaggerate the motion where animation itself fails.

“Wuh-uh-wuh-wuh-wuh-wuh-wuh-weh-wuh-wuh-wuh-what uh-wuh-wuh-wuh-wuh-wuh-wuh-was the-the-the-the-the-the-that?” Profuse and somewhat unnecessary, Porky’s delivery exists more as another means to grab laughs through his speech patterns, perhaps indicating more unconfidence from Clampett.

Thankfully, unnecessary deliveries veer towards a much more playful territory as Porky comes across the frog-induced cloak figure. Determined to have a vehicle for screwball antics, Clampett imparts Daffyesque “WOO WOO”s onto Porky as he is reduced to a shrieking, terrified mess.

Pure speculation and nothing more, Vive Risto very well could be the animator behind both scenes of Porky clawing at the wall (another parallel to Lonesome Ghosts) and opening the door to reveal the ghost—poses such as the antic of him landing on the ground after opening the door, the worried facial expression, and generally stout stature as a whole seem to mirror his scenes for the climax of The Daffy Doc. Regardless, whoever is the perpetrator of the animation, it is refreshingly frantic, elastic, and quick.

Upon coming face to face with the ghost himself, Porky struggles to escape through a moment of paralyzed terror. John Carey’s scenes of Porky’s hooves getting stuck on the floorboards of the ship in Kristopher Kolumbus Jr. are directly traced by the presumed Risto as the same charade is repeated.

Likewise with scenes from Frank Tashlin’s The Case of the Stuttering Pig. One of the last “fat Porky” cartoons, the animation of Porky scaling a winding staircase is thankfully much less sloppy or obviously cobbled together than Clampett’s attempts at putting his 1939 Porky head on 1936 Tashlin’s pig’s body in Chicken Jitters.

The same could be said for Porky diving into the ghost’s arms and blithering about how awful his encounter with said ghost was. Stuttering Pig’s shtick is repeated almost verbatim, but thankfully less obvious to a regular viewer. The bar may be low, but a victory is a victory, even if Clampett’s reliance on reused animation or plot points does come at times as a disappointment.

Clampett thankfully puts a slight twist on the formula; rather than having the ghost observe in ironic silence, he continues to further mock Porky by cooing “Whatsamatter, bay-beeeee?”

As such, Porky’s frantic descent down the staircase is spurred on through the ghost rather than coming to his own realization—the “LOOK OUT, HERE I GO” admits his shrieks again falls into the “joyously stupid” category. Such raw energy from a character like Porky, no less, is a delight given the pedestrian treatment of the character in so many of Clampett’s past (and future) cartoons.

Climax ensues. The pure amount of speed and energy exercised through the ghost pursuing Porky cannot be understated; perhaps knowing just how mindless and slow Clampett could get with shorts such as Porky’s Hotel, it comes as a greater relief with that in mind. Even then, the rapid pacing and borderline hypnotic speed in which Porky scrambles through the house, out the door—or, rather, THROUGH the door—, into his car and down the road is incredibly anomalous for 1939 Clampett and 1939 Warners as a whole. It serves as a worthy precursor to the rapid fire nature so inherent in Clampett’s later works.

That the climax is so short helps immensely. Much of Jeepers Creepers is padded through filler, and to a bit of a detriment. Regardless, that the climax is not included in said filler greatly benefits the cartoon as a whole—having to find ways to string the chase along to pad out a minute of the remaining short would be lethal. The chase as a whole doesn’t even last 20 seconds.

Unfortunate it is that the cartoon’s ending seems to drop off; the ghost makes a purposeful attempt to outrun Porky only to hound him for a ride. Having Porky speed off into the horizon, reverse, flash his “NO RIDERS” sign and speed off again would have been fine in itself—underwhelming, but maybe a steady enough coda.

Instead, Clampett relies on blackface jokes and radio references as a cloud of exhaust in the ghost’s face renders him a minstrel caricature. If anything is worth noting at all, is that Mel Blanc gives us his very first impression of Eddie “Rochester” Anderson, who would grow synonymous with Looney Tunes shorts as a whole through regrettably frequent and defamatory caricatures: “My oh my, tattletale gray!”

.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment