Release Date: September 2nd, 1939

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Chuck Jones

Story: Rich Hogan

Animation: Bob McKimson

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Margaret Hill-Talbot (Sniffles, Mice), Mel Blanc (Owl, Owlet), Berneice Hansell (Score-Keeper, Mice)

(In addition to being on HBO Max, you may view the cartoon here!)

The apparent hit of Naughty but Mice is immediately noticeable before the cartoon even starts—the existence of this cartoon to begin with, as well as the brand new “featuring SNIFFLES” title card. Clearly, both audiences and Jones himself were receptive to the character—the triumphant fanfare that blares after a gorgeously dramatic and imposing chorus of “Three Blind Mice” reflects a level of confidence Jones hadn’t completely mastered yet. Any confidence is good confidence, and this is a sign of good things to come.

As per the plot itself, Sniffles is leading in a scavenger hunt and only needs to capture an owl’s egg to win. Papa owl isn’t exactly receptive to the idea of Sniffles taking off with his little one—especially when said little one hatches and provides even more trouble.

Fade into a moody establishing shot of a farm. Stalling’s muted but cozy score of “Deep in a Dream” is a cute callback to Naughty but Mice, where the same number played as a repeated motif. Blue, green and yellow hues are rich and vibrant painted on the façades of the house, barn, and silo—likewise, a lone window from the house painted as a fiery, deep red and orange ombré is a subtle but powerful contrast to the remaining cool color scheme.

A series of truck in and dissolves reveal a cat dozing by the fireplace indoors, bestowing a functionality to Stalling’s song number choice. Though similar in design to the cat from Naughty but Mice, the feline here touts a slightly more sleek, streamlined design, outfitted with a gray ring around its eyes instead.

Enter our star; furtive footsteps reflected through string plucks in the music score clearly indicate that he isn’t in the cat’s vicinity by choice.

As it turns out, the object of his desires is a cat’s whisker, which he plucks off with a quick yet potent heave of effort. The cat’s eyes opening slightly as its face gets tugged is a small but strong detail that aids in conveying the movement of the pull, as well as inserting a slightly added risk to an already risky situation—there is no way that the cat will sleep through this.

Sniffles agrees. Though the sheer force of the pluck sends him flying feet backwards, through some unsteady maneuvering he’s able to gain ground and shift into a run cycle via a very articulate and smooth transition. Likewise, rather than displaying a laborious shot of the cat waking up and growing agitated, he instead flings himself with a yowl at the mouse hole in which Sniffles uses to depart. Similar to the cat’s eyes opening as his whisker was torn off contributing to the overall risk factor, the unannounced arrival of the cat reflects the panic in both Sniffles and the filmmaking; his entrance feels much more alarming and abrupt as a result, as though the audience is living the experience vicariously through Sniffles.

Such vicariousness is upheld in a series of solid perspective shots, particularly one where Sniffles grazes the foreground as he dashes down a set of stairs and turns a corner in the hallway. Though subtle, the jagged inking on his fur (namely his ears) solidifies his speed, as though he’s in such a hurry that even the tiny hairs on his ears are left blowing in the rush. The camera following him and trucking in through yet another mouse hole that he escapes from makes it seem as though the audience is following from behind.

Though a wide shot the chase being carried outside is comparatively cruder, slightly more stiff in motion, it remains engaging visually through obstacles such as a set of stairs or diving into a hole. Likewise, the camera continuously tracking Sniffles’ movements and following his descent still makes a point to immerse the audience in the action. It pays off well.

Jones’ growth as a filmmaker and director continue to be duly noted. That he launches the short off with such a bang is commendable in itself—though still padded through a series of establishing shots (the exterior of the farm, the sleeping cat), his cutting straight to the action with no explanation isn’t something he would have felt brave enough to do with his first handful of cartoons. Likely, establishing that Sniffles is participating in a scavenger hunt at a party (which is where our cartoon veers next) would have been the exposition, with the confrontation from the cat following that instead. Jones’ format here is more invigorating and engaging.

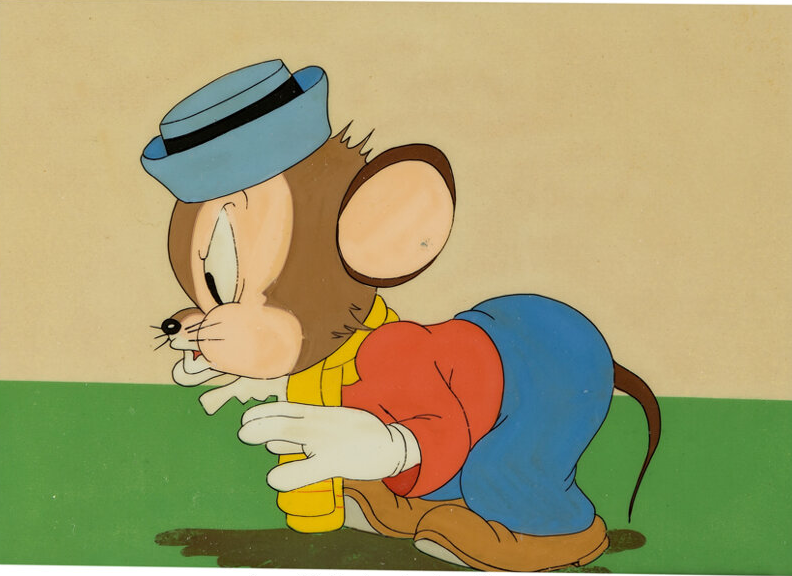

Bob McKimson unsurprisingly animates the endearing reunion of Sniffles meeting up with his fellow partygoers, whisker proudly in tow as he declares “I got it! I got it!” Carefully sculpted head tilts, gentle hand flicks and subtle acting choices such as a happy couple sharing an excited glance before alerting the rest of the party all work well in furthering Jones’ Disneyesque vision.

The atmosphere as a whole is welcomingly open and friendly, making Sniffles feel all the more endearing as a result; his mice friends eagerly share the news with each other through a series of excited head turns and jubilant squeaks. A stark contrast to cartoons such as Sniffles Bells the Cat where his buddies instead forcefully use him as bait to tie a bell around a bloodthirsty cat’s neck, the camaraderie and shared warmth places Sniffles as the unmistakable protagonist rather than, in this moment, the underdog.

“Didja reeeeeally get it, Sniffles?” In addition to a smattering of the mice in the crowd, Berneice Hansell provides her signature (and rather appropriate) squeaky voice for a scorekeeper mouse. Margaret Hill-Talbot’s own squeaky deliveries are equally endearing and mesh well with Hansell’s; slightly more grounded and less played for the squeaky shtick, but still equally--and lovably--juvenile.

Sniffles’ pause as he catches his breath before declaring a breathless “Sure! Here it is!” is a subtle yet amusing attempt at false modesty; his jubilated deliveries and seemingly effortless attempt at nabbing the trophy contradict his heavy breathing. His pride isn’t so much pompous nor egotistical so much as it is gleeful at the accomplishment—having escaped narrow death, his gratification is justified.

A close-up shot of the mouse’s record keeping book solidifies the context. Sniffles’ name being first and foremost (as well as having the most points after the inclusion of the cat’s whisker) yet again establishes a favorable hierarchy to his character in addition to clarity—there is no mistaking that this is his cartoon.

Moreover, the scavenger hunt in itself establishes an unspoken context and a story in itself—one inevitably wonders how retrieving a mouse trap would go, or a fly swatter, or a banana peel, how often they have these hunts to begin with, how many parties do they have, etc. Jones has learned that he doesn’t have to establish the story piece by piece to ensure the audience understands; the context clues will speak for themselves.

The score keeper mouse marks a proud X under the “CAT’S WHISKERS” tab, indicating the only item left for Sniffles’ victory is an owl’s egg. While the close-up itself may slightly be on the slow side, time allotted to show off some personality animation of the mouse tallying each X before reaching the designated spot, it provides ample time for the audience to soak in and enjoy the aforementioned details.

“Gee! Sniffles, all ya gotta get is an owl’s egg and ya win!” McKimson’s sculpted animation of the score keeping mouse coincides with Berneice Hansell’s hammy deliveries, dramatic head shakes and convulsions feeling slightly excessive but nevertheless pleasing visually. Likewise, Carl Stalling’s happy-go-lucky accompaniment of “I’m Happy About the Whole Thing” is very pleasing musically, a warm fit to a warm scenario.

Sniffles’ equally hammy and self-assured “Only an owl’s egg?” hints at oncoming conflict—the audience prepares for the venture to be less easy in practice. Nevertheless, a “Gee willikers!” indicates that our star rodent is up to the task.

While still far from his zenith, Jones has slowly been perfecting and refining his speed. Sniffles’ exit is so abrupt and brief--conveyed as a speeding blur of brown and tan--that even the partygoers appear surprised as the scene fades to black. His departure aligns succinctly with Stalling’s closing music sting, solidifying closure and finality.

Indeed, the next sequence of the cat sneaking out of the house feels much more sinister and foreboding as a tonal shift is swiftly established. Moreover, disgruntled rubbing from the cat on the spot of his missing whisker indicates that he holds a grudge and is ready to seek vengeance.

A take directed towards something off-screen proves such an impulse; upon seeing Sniffles heading to the barn, a slow camera truck-in yet again to track his movements and feel as though the audience is following him, the cat wastes little time in pursuing him. A momentary grimace from the cat before leaping off-screen is certainly of Jonesian sensibility.

In the early-mid ‘40s, Jones’ films grew exponentially experimental in their design. Staging, composition and layouts of a whole were viewed with a more graphically inclined eye—sharp, geometric angles, patterns, and an overall presiding geometry that often reminded the viewer of art before story. Such experiments would continue all through his career, especially when armed with design savvy, powerhouse layout artist Maurice Noble in the ‘50s and ‘60s, but a rather thick concentration of inspiration can be viewed in his early ‘40s films.

A very loose predecessor to such stylings is presented here. In a purposefully flat, horizontally staged composition, Sniffles enters a hole in the barn from left to right, reduced to a silhouette. His pursuer pounces from behind, yellow eyes breaking his silhouette and indicating a power dynamic via its ferocity. Sniffles’ scleras are not lit up—the cat’s are, which means business.

Of course, mere silhouettes are not so much a predecessor to the stylization seen in Jones’ later films, but rather the staging itself. Though Sniffles enters the barn from the side, the façade of the building itself is directly facing the camera, as is a silo in the background. Both the silo and barn split the screen into halves, used as a frame to direct the viewer’s eye to the cat and mouse. Such rigid angles and evenness to the composition as a whole feel purposefully artificial, design conscious. A pan upwards of the barn’s façade and fade to black rather than a truck-in and dissolve into the mouse hole maintains the presiding unconventionality.

Fade ominously into a sleeping barn owl. Though seemingly possessing less stylized awareness as the previous scene through more painterly, sculpted backgrounds, Jones still makes ample use of his shapes and staging; shadows in the background, wooden beam overlays in the foreground and the overall lighting frame a triangle around the owl, shedding a subtle yet baleful spotlight.

Similarly, that the owl is sleeping seems to introduce a stronger amount of suspense than what would be present if he were awake—consequences for potentially awakening or disturbing the owl are much graver than having him spot his prey from the start. With the owl asleep, Sniffles’ success at grabbing an egg and escaping seem closer in reach—as a result, the consequences feel much more dangerous and real.

A stronger, more literal spotlight is shown on the ever prized owl’s egg, nestled in a makeshift cradle. “JUNIOR” engraved on the front of the bassinet establishes a furthered possession on the egg than what was already implied from the egg’s existence itself—that, coupled with the close vicinity with its father, again raises the stakes of Sniffles’ mission. The joyful confidence exuded at the scavenger hunt is completely absent here.

Maintaining the vulnerable theme, Sniffles’ footsteps as he sneaks inside the barn are audible. The constant, vinyl squeak of his shoes immediately places a target on his back.

His vulnerability is noted through a cut back to the barn owl; with the din of squeaking shoes still creeping off-screen, papa owl heaves a few sleepy blinks as the worst case scenario is potentially realized—his rubbing against the shoulder of his wing is a small but strong addendum. Shoe squeaks reach an ominous halt as his movements grow broader.

A laborious yawn (coupled with some particularly strong posing and silhouettes) clues the audience into imminent danger. Sniffles’ ceasing of his footsteps feels foreboding in itself, as though he is watching just as closely from off-screen as the audience is. A confrontation seems like the only conclusion.

Thankfully for Sniffles, the owl settles back to sleep as Jones plays with both his and the audience’s nerves. Shoe squeaks resume off-screen right on cue.

Slowly, the camera settles back on the egg, a wide shot this time…

…to account for Sniffles’ arrival as he pops his head up from behind the crib. Slowly but surely, he snags the egg, the pool of moonlight from the rafters seeming to shine a spotlight on him like an escaped convict. Thankfully, he appears to make a solid exit.

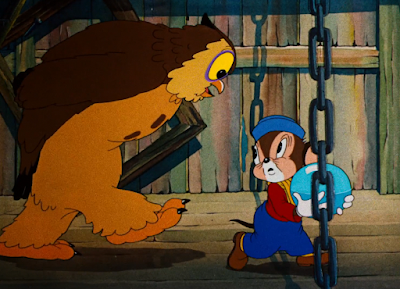

A technique often employed by Frank Tashlin in particular, Jones continues to tie Sniffles and the audience together to experience their reactions vicariously as he stumbles right into a stern papa owl waiting at the other end of the scene. Tashlin’s usage of the surprise technique had a tendency to be used more for comedic purposes—here, the intent is pure theatrics.

An upshot of the owl glowering at Sniffles, eyes twinkling with malice makes both Sniffles and the viewer feel small, meek, insignificant. Overbearing silence feels much more suffocating and chilling rather than any sort of introductory dialogue.

The deafening quietude is sustained as the camera cuts back to a wide shot of both Sniffles and the owl—a delayed reaction from Sniffles as he desperately tries hide the egg behind his back taps into Jones’ love of small delays and gaffes that make his characters seem all the more vulnerable and real.

Mel Blanc’s performance as the owl is delightfully chilling. His excessively amiable, squeaky deliveries drip with artifice as he drawls “Weeeell! Having fun?”

“Hmmm… what have we here?” Bob McKimson is yet again expertly cast for the demands of the scene; his acting on both the owl and Sniffles is rich, visceral, nailing both their respective emotions of sly confrontation and unconvincing inculpability respectively. Sniffles’ furious head shakes—a substitute for the words that refuse to jar loose from his mouth—immediately parallel Tommy Cat’s own head shakes in The Night Watchman, also animated by McKimson.

To assert his innocence, Sniffles coyly displays an empty hand. His pleasant grimace as he makes a desperate, quiet attempt to save face precede the same disingenuous body language touted by many of McKimson’s characters in his own cartoons.

Likewise, the owl sustaining his grin until the very last second--when he smacks Sniffles’ hand and causes him to reflexively hand over the egg--is a solid contrast to a shared disingenuousness. As soon as Sniffles forks the egg over, the owl touts his fake grin yet again; his reluctance to show any outwardly nasty behavior is almost scarier than the alternative. Sniffles and the audience both know he is hiding quite a lot of pent up anger behind his façade—it’s not a matter of if it will explode, but when.

“An egg!” McKimson’s slightly flamboyant posing on papa owl is great. “And a very pre-tty egg, too!” Sniffles’ facial expression of visceral, petrified discomfort transcends the screen.

“I once had an egg…” Papa owl hits every end of the spectrum, now turning melodramatic. Blanc’s vocals and McKimson’s acting make for a very convincing pair. “It was pretty, too…”

“It looked a lot like YOUR egg.”

Anger broiling to the surface, papa owl intimidates Sniffles into putting the “pretty” egg back in the nest—“before a certain little mouse gets himself HURT!?”

Enough praises cannot adequately be sung for both Blanc‘s vocal performance and McKimson’s meticulous animation. Blanc swings from emotion to emotion—stern to disingenuous to mournful to accusatory to threatening. McKimson on the other hand is easily able to match the personality and charisma demanded by Blanc’s performance in his animation of the owl. Even for Sniffles, who isn’t saying a word, his awkward grimaces and innocent blinks and open mouthed stares create a unique dialogue all for themselves.

On the topic of Sniffles, he dutifully returns the egg to its nest as quickly as possible. Going as far as to polish the egg by breathing on it and wiping with his sleeve on it is, again, a pure Jones move in displaying his characters comically overcompensating.

A cross dissolve back to the owl rather than a straight cut solidifies a sense of finality, transition—it is exceedingly evident that Sniffles won’t attempt to bargain with the owl. Instead, the owl attempts to bargain with him.

“Now don’t get me wrong… I have nothing against mice. Why, some of my best friends are mice!”

Sniffles’ grin at the age old spiel is hilarious in its own right; one would assume through the owl’s cloying tone that he would wise up and know better. Instead, he seems genuinely thrilled at the prospect of getting let off easy—innocent and impressionable first and foremost.

That all is rectified as the owl bellows in a grade A signature Mel Blanc yell: “BUT I DON’T LIKE YOU!!!”

With the force of the yell physically turning Sniffles backwards, the father owl uses this as an opportunity to grab him by his shirt and throw him out of the barn: “GET OUT!!!”

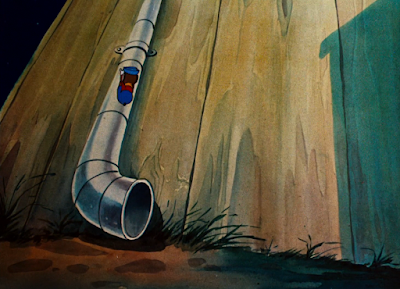

Cut to the exterior of the barn, where a hole and peg cleverly reminiscent of a birdhouse serve as Sniffles’ means of exit when he falls to the ground. Said fall is executed in a rather clever pan; though he is sent directly plummeting towards the audience in a dramatic and striking up angle, moon providing an excellent frame and visual guide for his arrival, both solid perspective and camera trickery continue to track Sniffles’ fall so that the camera switches to a bird’s eye view of his fall. While the fall could potentially be seen as slow (if one truly wanted to nitpick), it’s a rather impressive maneuver, especially from someone like Jones who hasn’t had tons of experience or time to experiment. The difference in filmmaking between this and Snowman’s Land, for example, is astronomical.

A cut of Sniffles landing on the cat from outside and being catapulted back into the air reminds us just how small he really is, to an almost jarring degree when paired with the perspective of the previous scene. Such is the goal—the brief interlude with the cat is not only a way for Sniffles to be catapulted back up into the barn (revealed to be hanging from the perch outside the birdhouse-esque hole), but serves as a reminder of his insignificance and power imbalance when juxtaposed with his adversaries. The underdog motif absent in the establishing scenes of the scavenger hunt and party is wholeheartedly present here.

After some stumbling and unsteady acrobatics on the perch, Sniffles makes an uneasy climb inside.

Fade out and back into the same sleeping shot of the father owl in the rafters, accompanied by the same foreboding music score. Jones’ parallels establish a momentous rhythm that is easy for the audience to digest, as well as an extra theatrical flourish as a whole; Frank Tashlin (who Jones’ short here draws numerous comparisons to) in particular was quite a fan of parallels to heighten his cinematography.

Likewise, the same truck-in on the nest as before solidifies the symmetry save for one minute detail: the egg is gone.

Enter egg thief. Since the owl, his egg, and Sniffles’ mission have already been introduced once, Jones spends less time dwelling on each aspect. The audience has absorbed the rhythm by now. As such, the egg now missing (and revealed to be in Sniffles’ clutches) is not only clever storytelling, but an equally clever way at throwing the audience for a loop and purposefully betraying the formula. Sniffles’ brisk albeit careful exit hints that a scavenger hunt victory is in immediate grasp…

…until a stray nail in the floorboards literally throw his plans for a loop. As Sniffles flops to the ground, the egg is thrown out of his care and into the nether regions of off-screen. A dull cracking noise indicates more trouble is to come.

Indeed, in another surprise reveal, the camera cuts to reveal a now broken egg in a much closer vicinity to Sniffles than what the wide shot leads on. Egg halves still wobble from the impact, fresh with motion. The camera halts ominously on one particular half of the egg…

“Hoot!”

The miracle of life unfolds before our very eyes as a baby owl pops unceremoniously from the egg. No purposefully saccharine Disneyesque antics, no coy giggles or bashful blinks seen by the likes of Bob Clampett’s own hatchlings in his cartoons—the closest thing towards any sort of infantile acting is a laborious blink from the owl. Its unmoving stare and static demeanor as a whole almost lure the audience into a false sense of security, as though the owl isn’t real, a fake-out…

Another “hoot!” swiftly puts such theories to rest.

With the audience thoroughly acquainted with the owl, Sniffles’ turn is next. Dazed from the fall, he slowly cracks his eyes open when a handful of “hoot!”s prompt him to get up and moving. A philosophy Jones has upheld from his directorial debut, having characters take spills, falls, or stumble over themselves introduces a defenselessness that is endearing and charming rather than inhibiting. The same could be said for Sniffles’ aimless scramble takes as he struggles to regain composure from being startled.

Sharing the audience’s potential apprehension at the validity of the owl’s existence, Sniffles himself leans close to the now unmoving owl in inspection.

Another “hoot!”, another solidification that the owl is very much real. Jointly, another series of startled, hat-grabbing takes.

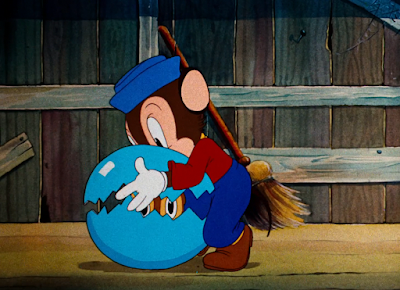

Knowing the squeak of his shoe was enough to wake the papa owl previously, Sniffles grows determined not to press his luck. Instead, he grabs the owl in his arms, folds him in half, and dumps him back in the egg half wear he belongs.

Considering the owl was already sitting in the egg to begin with, Sniffles realistically could have been just as well off by placing the second half of the egg on top as is—no need to lift the owl and fold him. But, much like his compulsion to polish the egg in front of the austere eyes of papa owl, his folding the owlet satisfies a need to overcompensate. If the father was to discover that the egg broke, at least his son will be sitting in their in tip top, folded shape—no hint of any mice interfering with the natural order. Though it seems like an odd maneuver on the surface level, it is instead a solid piece of acting and insight into Sniffles’ personality.

Hooting from the baby owl grows in both pitch and frequency once Sniffles secures it in the egg. A slight echo (as opposed to muffling the sound) exaggerates the gaping hollowness of the egg’s interior, further isolating the hatchling. That paired with Sniffles tying the egg with a string invoke more sympathy for the baby owl than for Sniffles. Props to the animator for some rather solid and accurate animation regarding the string tying.

“Hoot!”

An unpitched, echo-less hoot from the baby owl clues further abnormalities. Yet another wordless take from Sniffles asserts as such as the camera pans right to reveal the baby owl politely observing, free of any egg shaped barriers.

Sure enough, frantic endeavors to untie the egg reveal an empty egg shell. The entire sequence follows the logic seen in cartoons such as Jones’ Prest-O Change-O; such seemingly impossible or magical maneuvers are questioned by the characters themselves, but not so much the directors or the filmmaking. There is no reveal as to how the owl slipped out—no hole in the egg, no loose crack, etc.

Instead, the only explanation is provided through a knowingly absurd close-up of the baby owl, its pupils spinning around in its head as though to possibly poke further fun at Sniffles’ stupefaction.

More “hoot!”s provide adequate insult to injury. Having already followed the pacifist route, Sniffles resorts to more drastic and abrasive measures. A shove of the cap forward on his head means business.

Rather than exploring a labored sequence showing all of the various pins and hits and maneuvers to lock the owl back in its egg, Jones opts instead to shroud the entire scene in a cloud of dust; the fight isn’t important, but rather, the transition.

Such a hypothesis is proven as a vocalizing hatchling remains egg-free. Sniffles, conversely, is nowhere in sight.

Seemingly, that is.

Much of the pantomime acting and frustration comedy as a whole precedes a number of Jones’ upcoming cartoons. For a period in the early ‘40s, he would specialize in cartoons that would place a rather heavy emphasis on silent acting and slow burning builds—to name an example, Sniffles’ attempts to capture the owl feel reminiscent of Porky’s attempts to lure a rather expensive ant back in its cage in Porky’s Midnight Matinee; much of the staging and humor as a whole is based from slow burning frustration, heavy reaction takes, unexpected reversals, and a priority on pantomime acting as a whole.

Sniffles’ escapades here seem to be rooted more in innocence than the latter example (seeing as the ant is purposefully taunting Porky), but nevertheless serves as a possible indication to Jones’ feeling on the cartoon as a whole; while it may be a stretch to say shorts such as Porky’s Midnight Matinee are a direct consequence of Little Brother Rat, clearly Jones was either smitten with the setup or it resonated with audiences well. Both seem likely.

Knowing the mouse-and-owl antics can only be sustained for so long, Jones keeps things moving by having the owl obey Sniffles’ command to hop into the egg. Slight smears on his finger as he repeatedly gestures at the egg possibly reveal Ken Harris as the animator in question.

Of course, that would be too easy of a resolution. Yet another “hoot!” from the owlet prompts his legs to pop out at the egg’s bottom. Sniffles, still occupied with tying the egg shut, pays little attention.

His scavenger prize waddles out from beneath his grip as a result. Another flop to the ground cements his power imbalance and vulnerability—regardless of what vessel the owl is in or how it’s stuffed in, it will find numerous ways to outsmart his rodent adversary.

Sniffles’ tackling of the egg veers on the slower side, mainly to shed a spotlight on a rather smooth, sculpted run cycle. Much of the momentum of the run is aided by the rhythm of the camera pan; that too comes to a halt once Sniffles gets a grip on his prize.

A positive, reaffirming chirpy music sting from Stalling asserts the resolution as Sniffles tows his egg back to its rightful post. That he immediately scrambles out of the scene—paying no attention to the egg’s physical appearance or wear—indicates that the scavenger hunt is totally irrelevant now. If he doesn’t get the owl’s egg, so be it; avoiding the wrath of one angry papa owl is a much more important pursuit.

A gutter on the side of the barn is transformed into a mode of transportation when Sniffles uses it to slide towards the ground. His disembarking is slightly on the crude side, but brief and to the point—it is not a visual priority.

What is a visual priority, however, is Sniffles wiping his brow as he attempts to recover from the ordeal. Character animation is solid as ever, and the backgrounds are continuously moody. Priorities now seem to be directed towards concocting an explanation for losing the scavenger hunt.

“Hoot!”

Completely egg-less, Sniffles finds himself face to face with his little visitor. He opens his mouth in preparation to confront…

Both the audience and Jones himself have firmly grasped the formula of the cartoon. Further confrontation seems excessive and futile. As such, Sniffles flicks eyes his towards something off-screen in an indication of another shift.

The cat from the beginning of the cartoon wasn’t just pure filler; from a straight on shot from Sniffles’ point of view, the feline rounds the corner of the barn. Pulsating yellow eyes indicate nefarious intent. Likewise, inserting the idly bobbing baby owl in the composition continues to exaggerate the impending danger. A cat approaching Sniffles is bad enough; that the hatchling could be caught in the fire is even worse.

Realizing this, Sniffles retrieves his companion—but not before saving his own skin. Noting the aforementioned points and inherent pathos with the baby owl, the change of heart from Sniffles is executed. At this point, outrunning the cat isn’t so much a related to Sniffles saving himself rather than it is saving his friend. Impending footsteps from the cat continue to remind the audience of the danger; this chase isn’t just for pure thrills. It's also worth noting that in one frame, a piece of paper is seen at the side of the screen as it was accidentally photographed--likely the cartoon's exposure sheet/animator's draft.

Little Brother Rat is complex for a number of reasons. One of the most glaring points is that Sniffles faces not one adversary, but two (three if you happen to count the disturbances caused by the owlet)—two adversaries who slightly differ in their motives but have a similar end goal. Papa owl makes his presence known as he pokes his head out from the hole in the barn, a scowl on his face indicating vengeance is imminent. More impressive perspective animation is touted as he soars out from the barn and glides into the foreground.

That the climax is executed almost entirely in silhouette again notes Jones’ growing embrace of stylization and engaging cinematography. In fact, the only break from the stylization is to shed a spotlight on Sniffles yet again tripping and losing his owlet upon the realization that the papa owl was targeting the cat instead.

Juxtaposition between the yellow glowing scleras of the owl/cat and white scleras of Sniffles/owlet deceive the audience into following an “us vs. them” format—the white scleras of Sniffles and his owl friend supposedly indicate purity, whereas the yellow scleras of the owl and cat are more imposing and chilling. Thus, the papa owl grabbing the cat and dropping it in the house’s chimney comes as a surprise, even if it is a rather obvious decision in hindsight. Jones continues to keep the audience on their toes all through the cartoon.

Fade out and back into the true resolution of the cartoon. Stalling’s homely reprise of “I’m Happy About the Whole Thing” serves as a fitting bookend to the opening of the short where it played during the party setting—especially considering the papa owl bestows Sniffles the empty eggshell in his gratitude. As always, Bob McKimson’s character acting is meticulous, sculpted, and actively appealing. Likewise, papa owl’s “Goodbye, my boy,” is a charmingly warm and sentimental footnote for the cartoon to end on. A stark contrast to the exceedingly foreboding introduction of the same owl.

Correspondingly, a celebratory “Gee willikers!” from Sniffles parallels the same exclamation heaved at the start of the cartoon when learning his next objective for the scavenger hunt.

Segueing next to an up shot of papa owl and his owlet on the perch above the barn sustains the sentimental innocence of the cartoon’s end. The same can be safe for Sniffles’ reciprocation of the gesture.

At long last, Sniffles prepares to haul the egg back to the party. His contentedness seems sourced much more from the reunion than the prospect at winning a game—one wonders how much that would have changed if this cartoon had been made a few more years down the line.

Even then, a topper is imminent. A crack of the egg and a “hoot!” from an identical baby owl leaves Sniffles just as puzzled as the audience—the ambiguity between whether or not the owl in the egg was the original owlet from before and that the baby Sniffles rescued from the cat was another newborn or that this is just an entirely new, reality-breaking owlet as a whole leaves for a welcome end that is amusing and cute more than puzzling.

Jones’ early desire for warm, endearing storytelling has often been lambasted for being too slow or banal, and at times that can be true. Little Brother Rat is not one of those instances. In fact, such a focus can be a great strength—though he was the outlier when compared to the irreverent, fast paced humor touted by his coworkers, sentimental endings (and cartoons as a whole) such as these stick out twice as much when compared to the competition. In cases like this where the warmth is particularly potent and successful, Jones is almost stronger for differentiating himself from his peers. One would not find the same filmmaking or pathos in a Ben Hardaway cartoon.

Some view it as a weakness that it took him so many years to succumb to the more brash humor that was the Warner Bros standard. There is certainly truth in that, but had he not resisted the temptation sooner, perhaps we wouldn’t have been treated to gems such as these.

As mentioned before, Little Brother Rat is a masterpiece compared to the likes of Snowman’s Land. Even on it’s own, it’s a great cartoon. Consistency, rhythm, staging, acting, tone, story, and so forth all gel together smoothly and clearly. Sniffles continues to establish himself as a heartily endearing character—while Naughty but Mice derived much of its humor from Sniffles exclusively (particularly as a result of his being drunk for half the cartoon), the focus here is more on his reactions to other situations and characters, which is often just as important as his own innate acting.

Likewise, and as was mentioned previously, the sophistication of having two separate adversaries and storylines tie together into a whole is an exciting step forward for Jones as a director. While the climax may be comparatively short next to the rest of the cartoon, where some parts could be seen as running on the longer side (particularly the struggle to get the baby owl back in the egg), it is still a clever first attempt at such a convergence. Particularly inspired artistic and design choices further contribute to the cartoon’s success.

If Little Brother Rat truly was the basis for cartoons that follow a very similar execution, such as Porky’s Midnight Matinee, it certainly isn’t difficult to see why. While—regrettably—not every Jones entry that follows a similar format is up to the same level of quality as is displayed here, one certainly can’t fault Jones for trying to replicate his success. From the art direction to the acting to the story to the ensemble as a whole, Little Brother Rat makes a very solid argument as to why Jones would want to further his more saccharine expeditions. It proves difficult to argue with the sheer charisma and comfort exuded from this cartoon.

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment