Release Date: October 7th, 1939

Series: Looney Tunes

Director: Bob Clampett

Story: Warren Foster

Animation: Izzy Ellis

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Porky, McCoy, Duck, Cow), Shirley Reed (Petunia), The Sportsmen Quartet, The Rhythmettes (Chorus)

(You may view the cartoon for yourself here, or on HBO Max for those who have it!)

With only one Petunia short under his belt previously, Bob Clampett calls curtains as Petunia makes her final animated appearance. She would instead pursue a mildly popular venture in the Dell comics and pop up in a hefty amount of merchandising—given the outcome of this cartoon, it may be for the best.

Having been visited by directors such as Friz Freleng and Tex Avery, Bob Clampett throws his own hat into the feudin’ hillbilly family ring as Porky and Petunia, leaders of two feuding factions, finally put an end to their war. However, they seem to be the only ones content with the pact, as their respective sides are quick to retaliate against each other.

On a mildly unrelated note, one of Clampett’s handful of “STARRING PORKY” title cards has gotten a somewhat fresh coat of paint: rather than just a disembodied head, Porky’s headshot is now benefitted with a body painted below the cel overlay.

In an era where opening cards of text are often used as facetious disclaimers, means of padding time, or—typically the most often occurrence—both at once, Naughty Neighbors’ establishing text (while still a time filler in itself) provides a much more functional purpose. From the pseudo-lace embroidery to the demure, saccharine musical accompaniment, Clampett and Carl Stalling both do a great job of lulling the audience into a false sense of security.

That is, a false sense of security that is shattered immediately after a fade out to black and back in. Said peace and harmony boasted by the hill folk is depicted through raucous shooting, kicking, clubbing, and bombing. A riotous musical accompaniment of “The Old Apple Tree” and whimsically deafening sound effects from Treg Brown effectively betray the carefully sculpted image alluded to in the exposition. While the animation of the denizens is crude in its design, its prioritization on energy and rapid movement further the mood and tonal contrast, which is most important.

A bomb exploding in the foreground provides a creative means of transition as we return to a more temperate change of pace. Always a fan of conveying plot through newspaper headlines, Clampett’s interminable gazette this time alerts the audience to the end of the feud through a non-aggression pact. Knowing Porky and Petunia’s romantic past and incongruously cute disposition, considering the build-up to such a wholly violent feud is amusing in itself.

Likewise, various Easter eggs are slipped all throughout the front page of the paper; that the cartoon mysteriously takes place in 1942 rather than 1939 is oddly specific and questionable in itself—a fresh headline about the sinking of the Titanic serves as Clampett’s playful acknowledgement of the time shift. Animator John Carey himself also gets a shoutout through a birth announcement on the leftmost side of the page. Moreover, Porky’s euphemistic label of “The Real McCoy” seeks to embrace the near fetishistic reliance on wordplay so prominent through this particular time period of Clampett cartoons.

Attempts to fill up time are incredibly obvious through disclaimers, newspaper headlines, and scenic pans that move at a crawl; still, they prove difficult to fault completely, especially when paired with the sleepy chorus of “When I Yoo-Hoo” in the background. Dick Thomas’ background paintings are a visual treat as always, but feel particularly picturesque during certain parts of the cartoon.

Still, that it takes nearly 2 minutes into the cartoon before a line of dialogue is uttered proves to be excessive. It doesn’t read as a stylistic choice more than it does hesitation and filler.

Nevertheless, both leaders of the Martins and McCoys assert their truce through painstakingly cloying saccharinity absent of the wit so usually present. Eyelash flutters and hugged knees and other general displays of mawkishness feel forced, incongruous; knowing Clampett’s previous habits of using such treacly endeavors as a segue to brash, screwball or violent hysterics immediately afterwards, one almost expects the same outburst to occur. An underlying sincerity was always felt in Clampett’s bursts of cuteness, but to play it completely straight as it’s done here is a surprise, and not exactly for the better.

Petunia (whose voice has been considerably sped, doing little to alleviate the nauseating sweetness) giggles to Porky about how happy she is that their “quarrel” has been patched up, much to Porky’s agreement.

“Yeah. Uh-neh-nih-now that we’ve buh-be-bih-buried the hatche-ehh-ehh—buried the ha-eh-it-it—tom-ee-hawk, heh…”

Similar to Porky’s Hotel, much of Porky’s dialogue consists of various switches as a substitute for any real acting or substantial personality. It’s not nearly as concentrated in such a short amount of time as the former example (nor does it feel quite as forced), but the struggle to get a running start is certainly felt.

“…We can be muh-mih-ma-eh—we can be ehs-ehs-eh-sweet-eh-sweethea—eh, we can be eh-ff-fr-frie-eh-feah-eh… we can say hello.” That the dialogue in question being switched is actually somewhat amusing helps considerably.

The false pleasantries so absent in Porky and Petunia’s interactions are thankfully counteracted through the adjoining scene of two elderly birds. Praises are in order for the designs of the duck and the rooster—or, rather, their coloring. Completely inverting their color palettes (the duck has black feathers, the rooster’s are white, duck’s hat and beard are white, rooster’s hat and beard are black) signify obvious parallels whose contradictions form, ironically, a strong harmony between them.

“Well, Snuffy…” Mel Blanc’s stereotypical old man voice is par the course but adequately directed. “Who woulda thunk that after all our feudin’ and shootin’ that you Martins and us McCoys would be friends.”

Slight error on the duck’s declaration of the familial factions—a cut to the next shot shows that the duck himself is a Martin and the rooster a McCoy. Likewise, Porky later solidifies the error, labeling the chicken a Martin and duck a McCoy by pointing at them through his respective dialogue. It certainly isn’t nearly an obvious gaffe to serve as an active detriment to the story, but is somewhat fascinating—especially given that the issue is repeated.

Regardless, the timing between the amiable pause to both birds sticking their faces together and Blanc screaming “IT’LL NEVER WORK!!!” is priceless and easily one of the cartoon’s highlights. With their heads together, the simultaneous differences and similarities between the two poultry are as keenly noted as ever, especially with the color differences in the beards and hats. Lovely stylized flatness in their side profiles—one mourns the cartoon that could have been had this same energy and inspiration been maintained at an equal pace all throughout the short.

Outside of the confusion maintained by Porky’s erroneous labeling of the two factions (pointing to the rooster as he says “Eh-nuh-ne-nuh-ne-eh-now you Martins…”, the duck at “…eh-eh-and mih-uh-mih-me-mih-me-meh-McCoys eh-ge-eh-ge-eh-get t'gether an' bih-be-beh-be-eh-beh-be-beahh-be good boys!”), the size discrepancy between the pigs and the poultry is jarring at best. If the duck and rooster were truly meant to be as small as they are, the background perspective in the former scene completely betrays that—the width of the boundary line is relatively the same for both sequences, and the horizon line likely would have been raised much higher with less visible sky/taller trees to convey their diminutive height.

Nevertheless, after a brief bout of bashfulness the poultry shake hands. All around, contrast is surprisingly well maintained, whether it be as obvious as their designs or more subtle such as their posing. While the duck coyly plays with his beard, the rooster makes a point to turn his own chin away and scratch at his chest. When they shake, the duck looks down, the rooster looks up.

Though tangentially related, interesting to note is Porky’s contemplative and somewhat disdainful wink at the scene’s beginning—Clampett’s influence is particularly felt, as it was an acting choice he defaulted to often in his own animation work.

Enter the song number of the cartoon. It certainly does a good job at filling up exactly a minute of the short’s runtime and very little else. Set to “Would You Like to Take a Walk” (albeit outfitted with substitute lyrics), it too is a disgustingly sweet amalgamation of tooth-rotting romance with very little wit to balance it out (unless “wit” counts as a cow saying “Who, me?”, a skunk shaking hands with a rabbit donning a gas mask, or an admittedly fun shot by John Carey with Porky and Petunia their asses as they walk down the lane.)

Porky’s failed attempts to harmonize and being overcome by his stutter is a fun bit of acting where the stutter feels necessary and welcome as a joke rather than forced, and Dick Thomas’ backgrounds—particularly the final two shots of the song—are absolute eye candy. Otherwise, it unfortunately reads more as obnoxious, grating, and incredibly obligatory rather than a whimsical, catchy musical interlude. The issue isn’t the cuteness by itself, but moreso cuteness without spirit. Saccharinity that feels incredibly manufactured, uninspired, tired rather than appealing or warm.

At the very least, much of the shoehorned sappiness is rectified through the forthcoming sequence, which is again one of the cartoon’s highlights. Here, a duo of ducklings waltz together with the aid of aggressively Disneyesque atmosphere.

Similar to the design differences between the old rooster and duck, Clampett establishes a sort of gender binary between the two ducks by having the white duckling’s hair tufts point downwards (like long hair) and having it pull its tail feathers out like a skirt. Arbitrary as it may be to establish, it’s a very clever use of economy in design outside. As far as parallels in this short go, Clampett has succeeded.

Likewise, the saccharine chorus hummed in harmony and Dick Thomas’ utterly gorgeous circular framing of the scene with various flora. A great juxtaposition between the dark, bold black of the foreground and lighter, softer grays and whites in the background.

Of course, the Disney influence is not so much the priority as is the complete desecration of it. After each chorus of hums, one of the ducks slams the other to the ground in a violent, rapid fit before resuming the waltz.

Other duck retaliates in equal form.

Each duckling now on equal footing, Clampett splits the difference by having them engage in a mutual, tense stand-off. It is important to note that the same dance and quaint humming resumes as unobtrusively as possible after each round of violence or tension.

For the fourth and final time, another mutual standoff is delivered by having both ducklings konk each other on the head at once.

This is the true beauty of Clampett’s cute tendencies. A mischievous spirit lingers behind the deliveries present here that is wholeheartedly absent in the song number or much of the exposition as a whole, which is criminal. Though the acting, animation, character designs and synonymous, parallel structure as a whole are all great contributions of success, much of the sequence’s magic lies in Stalling’s music score and Treg Brown’s sound effects.

During each violent altercation, Stalling ceases the music altogether. As such, Brown’s violent thuds and smacks that echo off the screen are given a particular highlight and seem to exaggerate the pain and rapidity (which is already well conveyed through multiples of each duck getting jostled about, the gradient coloring creating a pseudo motion blur.)

Forced pleasantries are upheld as the camera returns to the chicken and duck from before, continuing their game of patty cake as seen during the song number. A reprise of the chorus asserts the familiarity, and a particular emphasis on loud smacking sound effects hint at inevitable violence. Hilariously disingenuous facial expressions support such a theory.

Much like the duckling dance duet, violent, strategically timed blows to the head are interspersed through the surprisingly constant game of patty cake. Timing each hit to the music (especially during the final chorus, where each blow is accented to each corresponding syllable from the singers) maintains a constant rhythm in both pacing and instrumentality as a whole. Simple, clear staging with the boundary line splitting the screen in half—again, not unlike the ducklings—sustains parallels, which, in turn, sustain clarity, patterns, and familiarity, enforcing a cohesiveness that the short as a whole could greatly benefit from.

Nevertheless, all good things must come to an end, and said end is enforced forcefully through a mutual shower of bullets from the feuding poultry. Dazed wobbles and aggravated head swaddles somewhat inflate the scene more than necessary and feel bloated—a slow reach for the pistols on a held pose and spontaneous burst of gunfire may have held a sharper contrast rather than aimless movement. Regardless, it is exceedingly clear that rounds of patty-cake are again a thing of the past.

Somewhat curious is the next scene of a duck bugling into a cow’s horn as a call to arms; his ambiguously Daffyesque design does leave one wondering. The overall construction, proportions, and brief spotlight on the character as a whole all seem like an oddly specific decision; compared to the other ducks seen in the cartoon, the overall appearance of this guy seems to reminiscent not to be. On the other side of the coin, excising the ring on his neck would seem like an equally odd decision. I personally have always assumed it was a Daffy cameo, but have no proof to back that up other than I love the character and would likely enjoy the cartoon more had he more prominence.

Nonetheless, Daffy or a mere relative of blowing into the cow’s horn is welcome—the pained expression on the cow as her poor eardrums are mercilessly shattered introduces a comical unwillingness on her part and elevates the sequence outside of just “one item becomes another”.

It would not at all be a Bob Clampett cartoon without recycled animation. Here, the shot of a mother duck checking on her little ones is heavily reminiscent of a similar shot from Wise Quacks; likewise with the eggs hatching to reveal little duckling soldiers sourced from What Price Porky. Though the synchronization of the ducklings is fine on its own, the 3/4 perspective falters when paired with the flat, horizontal background—the ducks seem disjointed from their environments and appear to glide on top of the background rather than march in it.

Similarly, some of the animation from the opening (a dog firing a rifle in the bottom left corner, another clubbing his rival over the boundary line sign, two dogs kicking each other, two ducks firing pistols at each other) has been cribbed with new animation. To Clampett’s credit, he resisted the urge of completely reusing the aforementioned shot, going so far as to introduce a slightly new layout angled more towards the McCoy side, but—as was said in the review of Jeepers Creepers—the bar is low.

So low, in fact, that a 1936 Jack King cartoon, Boom Boom, is the source of the next gag and piece of cribbed animation. As was the case in the former example, a duck gets the jitters after repeatedly firing a machine gun. The usage here thus confirms that the much of the animation of bombs exploding at the beginning was further cribbed from Boom Boom—particularly the shelling exploding in the foreground and sparking the dissolve to the newspaper.

Clampett’s next piece of reuse gets a pass seeing as it was used by other directors such as Art Davis in his Holiday for Drumsticks. With a mama’s kittens crying for milk and not enough cans to feed everyone at once, her problems are solved by holding the can of milk in the air.

Just like the source—said source being Tex Avery’s A Feud There Was—bullets pierce the milk can, creating a steady stream of milk for each kitten to reap from. That a handful of kittens go so far as to bathe in the milk stream like a shower somewhat elevate it above purely cribbed material—the effort is appreciated.

If Porky’s affections towards Petunia consist purely of him offering her a flower while they both awkwardly bob their heads and move aimlessly, then this being her last outing may not be such a loss after all if such an action is indicative of future endeavors together. More and more, Petunia appears more like a mandate rather than a character Clampett returned willingly—she feels incredibly more shoehorned in than she did in Porky’s Picnic, which was felt enough as is. It’s very clear that Clampett’s heart was not in pursuing wholly sincere lovey-dovey ventures; if it was, he would not have deliberately sidelined the two of them for so much of the cartoon.

Porky regardless catches wind of gunfire in the distance, and, through a rather calculated maneuver that loses its intended spontaneity, drags Petunia back to the hillside where they can view the violence for themselves.

After more stuttering gags with Porky (“G-gih-gih-eh-gih-eh-gosh! They’re eh-feud-ih-ih-feud-fih-feud-ih-feud-ih-eh—fightin’ again!”), Clampett reprises a beloved physical gag with a fresh sheen of coat.

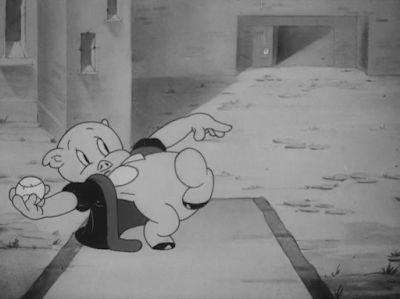

As Porky runs towards the feud, rather than dodging a handful of bullets by jumping out of his overalls and ducking back in through quick succession (as is displayed in Inj*n Trouble and Porky’s Movie Mystery), the momentum is kept going as he ducks first , then returns to normal, then jumps up before resuming back to his regular disposition. While it loses some of the energy and spontaneity touted by the animation of the previous two examples, it succinctly establishes an adequate parallel momentum.

Thankfully, the audience is greeted with some attractive John Carey animation of Porky skidding into his house and a close-up of his retrieving a “FEUD PACIFIER”. Whether it be an impressive burst of perspective animation on Porky skidding to a halt in front of his dresser or something as mild as the folds on both his shirt and skin in a closeup, Carey’s penchant for solidity is constant and confident.

Moreover, Stalling’s dainty reprise of the song’s chorus as Porky unearths a grenade—hearts on the front, no less!—is the perfect blend of Clampettian sadistic cutesiness that IS wholeheartedly effective. The “pacifier” in “feud pacifier” on the box carries rather grotesque and horrific connotations with the reveal in mind. Likewise with Porky’s certifiably pleased grin off to the side of the screen.

Such a contrast is made twice as potent through the abruptness in which panic resumes from both Porky and the filmmaking as a whole, an elastic running take from Carey maintaining an ideal amount of urgency that feels mischievous and whimsical more than forced or obligatory.

His speed as he rushes along the winding country roads is serviceable to the action and story at hand. While it certainly could be faster, especially knowing just how quick Clampett could get (such as the end of Jeepers Creepers) Porky running in itself isn’t so much a priority as is the details of the feud pacifier.

A quick repeat of the earlier shot with the families clobbering each other serves more as a means to familiarize the audience and remind them just how violent the feud is rather than an excuse to pad time (though it helps with that, too.) The impact of Porky throwing the grenade wouldn’t be felt to its full potential had he tossed it immediately—reminding the audience that there are real people he is about to potentially kill and impact seems to solidify the conflict and magnitude of the situation.

While somewhat excessive, Porky kissing the grenade works as a great topper and also appears to cement his own masochism; he very clearly understands the consequences of what he is about to reap and does not at all seem bothered by exploding both sides of the faction (which includes his own) into smithereens. Again, this sort of gaily oblivious and inherently sadistic attitude is where Clampett is at his best.

With animation referenced from Kristopher Kolumbus Jr., Porky exercises little hesitation as he tosses the grenade. That a chicken clobbers a dog over the head at the exact time the explosion occurs seems to further exaggerate the impact and rhythm of the explosion.

Of course, ending the cartoon with total decimation and mass death would be too dark for Clampett (at least this early on.) Heart decals on the grenade play a reason; now, the hill folk truly do live up to their peaceful disclaimer and make a point to overcompensate as games of marbles are played, balls are tossed, maypoles are used prominently and (my personal favorite) two ducks kiss on the lips as purposefully mechanically and vacantly as possible. A cloying falsetto of “Here We Go ‘Round the Mulberry Bush” in the background is the perfect topper—the stark contrast in such a short amount of time is very effective and funny.

Porky and Petunia still have their own finale to make. Cloying saccharinity morphs from ironic to forced attempts at sincerity as a female chorus reprises the song number for a final time—animation is directly reused from Porky’s Picnic (mercifully sans mud/eventual blackface) as Petunia smothers Porky in a kiss.

Clampett manages to squeak a final good note to the cartoon as a duck, voiced by the great Danny Webb, sings in a frog-throated chorus on par with the lyrics: “Something good will come from… THAT!”

A wink as we iris out allows the audience to ponder such promiscuous implications.

While not outwardly devoid of any sort of inspiration, wit, or energy like Porky’s Hotel, Naughty Neighbors is unquestionably one of Clampett’s weakest cartoons. Which, with that said, is a somewhat optimistic deduction, as not every director is able to say the same for their weakest.

Neighbors has quite a number of redeemable aspects: its various parallels, juxtapositions and overall symmetry is incredibly effective and makes for some very funny gags or momentous flow. Antitheses between the opening disclaimer and the juxtaposing bloodshed or the various by the animals to play nice and letting their vicious impulses get to the better of them make for the best parts of the cartoon. The ducklings dancing together or the poultry patty-cake, as well as the concept of the feud pacifier as a whole illustrate just how strong Clampett’s adoration of cutesy sadism can be. When pulled off well, as it is in those instances, it becomes no secret why he employed it as such a recurring theme. Parallels between character designs—again, the ducklings and the old birds—are refreshingly mindful and strong. Stalling’s music score and Brown’s sound effects carry much of the cartoon, and Dick Thomas’ background paintings are really given a chance to shine.

Keeping that in mind, little else of the cartoon is worth acknowledging. A heavy reliance is bestowed upon borrowed gags or animation, and while audience members in 1939 likely wouldn’t realize that themselves, it becomes a hard point to wholly disprove when there are other cartoonists in 1939 making cartoons who didn’t have such a heavy dependence on recycled footage or jokes. How the animation is applied is more important than recycling it to begin with, but said application here feels very uninspired, stale, obligatory. This cartoon as a whole is very short, clocking at a 6:19 minute runtime—so much of it is comprised of filler or complete displays of transparency. It is very clear that little inspiration was kindled by Clampett, and what kindlings there are to find are delegated to anyone but Porky and Petunia.

As was mentioned previously, this is Petunia’s final cartoon. If this short is anything to go off of regarding her (or Porky’s) future, ending her animated career here and now is a mercy kill. It’s truly a shame that female characters in these shorts aren’t given a bigger spotlight, but so much of it comes from a complete inability to write compelling female leads outside of one-dimensional stereotypes or traits guised as personality.

It’s very clear nobody knew how to write Petunia. Likewise with Porky’s attraction to her. Setting up consistent romantic leads is a liability—romance in Warner cartoons is more akin to Daffy buying a 10¢ wedding ring to marry a woman for her money (such as in Friz Freleng’s riotously funny His Bitter Half) rather than “Porky has to hold a flower out to Petunia because we’re contractually obligated to have the both of them appear in the same cartoon”.

As a whole, Naughty Neighbors consists largely of Clampett’s bad habits and tricks that try to lure the audience into thinking the short provides more substance than it actually does. Attempts to disguise a lack of inspiration almost seem to make said lack of inspiration even more obvious. Frustratingly, it has its good qualities—and quite a handful at that. That this cartoon does have little bursts of spirit and inspiration almost makes the wound sting more as a result. If the same inspiration, passion, and devotion touted by the best parts of the film were consistent throughout the entire short, it really could have been something great.

.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment