Release Date: October 12th, 1940

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Tex Avery

Story: Dave Monahan

Animation: Chuck McKimson

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Gil Warren (Narrator), Mel Blanc (Baby New Year, Tommy, George Washington, Washington’s father, Dog, Fox, Son, Turkey), Sara Berner (Baby, Girl, Mother), Tex Avery (Dean)

(You may view the cartoon here!)

Another day, another spot-gag directed by Tex Avery. Familiarity of Avery’s directing patterns is comforting, in a way; he found a working formula to satiate both himself, his bosses, and his public. Repetition of the spot-gag format may wear on modern viewers who view said shorts in quick succession—a pattern in which they were never meant to be viewed—but it grows difficult to rise genuine outrage over a cartoon that seeks to entertain its audience and nothing more.

Holiday Highlights is a welcome subversion on the tried-and-true format regardless. That is, it is presented as a time lapse; an exploration of the year’s holiday as the calendar marches forth. From big holidays such as New Year’s and Christmas, or little ones such as George Washington’s birthday and Arbor Day, Avery and writer Dave Monahan both have a lampoon or two up their directorial sleeves.

While the tone of the short is easy to surmise through the title alone, opening to a calendar of the year’s dates clinches the notion. In fact, the calendar is presented before the title card—that is granted entry by bursting through the calendar through stop motion photographs of the calendar paper ripping apart.

It's worth mentioning that the technique is reprised from Picador Porky--another Avery entry in an era where his sensibilities were much more different than they are.A musical crescendo of “Ain’t We Got Fun” upon the title reveal makes the shift more poignant and exciting. A fun time to be had by all. Worth noting is that the dates on the calendar align with the exact calendar dates for 2023; allotment of said dates corresponds with the 1939 calendar year, shedding a potential glimpse as to how long this short was in production for.

“Tonight, we present a pictorial revue of some of the well known holidays of the year.” Gil Warren steps up as our velvet voiced narrator, as opposed to the usual casting of Robert C. Bruce. Whereas all of the holidays are presented through a calendar interstitial, only the introduction of New Year’s Day is demonstrated as a painting of an actual calendar. Segues from hereon are animated, engulfing the entirety of the screen. A comparative distance shot of the calendar merely seeks to acquaint the audience with the pattern established by the cartoon.

Avery opens the film with an artful touch—unsurprising, as he as proven himself time and time again to approach his cinematography with a striking visual awareness. Regardless, it’s rare for him to play a montage such as this one as straightforwardly as he does. Overlays of bells chiming, horns blowing, and champagne pouring harkens back to deliberately “high brow” cartoons such as Page Miss Glory, whose heavy emphasis on design was not Avery’s idea. Avery’s art direction has gotten much more constructed and dimensional since then, as this montage demonstrates. It is relatively cut and dry—no intricate angles or excessive camera trickery—but it is nevertheless a welcome change of pace from his typical manner of directing.

“First, we welcome the little New Year.”

Sara Berner expertly channels Baby New Year’s aimless baby babble. Again, comments of Avery’s growing dimension in art direction garner further admiration. Crawling of the baby feels believable in its staggered weight and momentum, solid draftsmanship allowing Warren’s comments on how cute the baby is to hold water. The effect wouldn’t have been the same if this short were attempted three years prior.

Expertly crafted cloying exposition proves to be functional, too—an innocent antithesis is constructed against the raucous, brazen, certifiably adult strains of Mel Blanc emanating out of the tyke’s mouth as he rings in the new year. Not only does having the baby cavort by standing on his legs provide more room to move, enunciating the hysterics needed to cement a visible switch in demeanor, it also represents a metaphorical shift to manhood. “Manhood” used liberally, in the same way that the grown timbre of Blanc coming out of the baby’s mouth represents “manhood”. The baby is already human, so describing the change as a sudden burst of anthropomorphism seems redundant, but is nevertheless somewhat truthful as the range for acting and hysteria is expanded.

Avery bookends the screaming and hollering and jumping just as he started—picking up with Berner’s baby babble as the infant toddles along on his way. The scene, being one tangent among many, feels more balanced as a result. Praises regarding the shadows tracking the baby’s movements smoothly and believably are also in order.

After January comes February, and with February comes Valentine’s Day. Our animated page turning interstitial is the first of many, establishing the rhythm in which the segments will be introduced from hereon out as indicated beforehand.

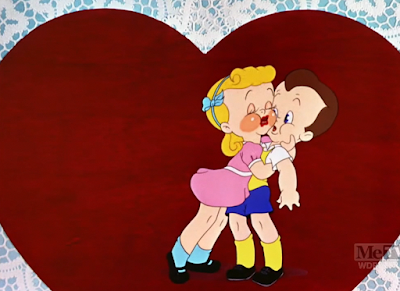

While Valentine’s Day is a holiday that boasts no age limit, it does especially bring to mind those school-hood days; hastily scrawling out valentines to share with students in your class, eyeing the inevitable candy pile awaiting to be amassed. Thus, two schoolchildren exchanging valentines are the subject of Avery’s directorial lens next. Keeping in line with his tradition of curly haired blondes to indicate youthful children, a girl coyly offers a valentine to her Tommy…

…who accepts it as the overzealous Casanova he is. Animation and vocals are harmonious in creating a joyous amalgam of utter creepy sleaze; Blanc, again supplying the velvety voice of a fully-grown man’s injects a sincerity in the passionate vocals. The joke being, of course, that Tommy’s means of romancing are much more “advanced” than the ho-humming of a typical school-hood romance (though his performance teeters on animalistic if anything.

Draftsmanship and motion of the drawings is tight, believable, a fitting vessel for Blanc’s vocal performance. Like the scene with Baby New Year, the same effect wouldn’t have been achieved without the control of the animation. With such a focus on physical affection, the motion needs to be anchored, tactile, weighted. Thankfully, by casting Rod Scribner as the animator, all of the above are achieved—with an added dynamic flair native to Scribner’s style that keeps it energetic and lively.

Before things get creepier, our humble narrator intervenes. Not to stop the hijinks—that would take the wind out of Avery’s comedic sails—but to redirect. “Don’t you realize this is Leap Year?”

Indeed, Valentine’s Day on a leap year once spawned the tradition of a woman to take the lead over her man. Our blonde heroine immediately gets the gist; her grin says it all.

The punchline is one of Avery’s oldest tricks in the book. Berner’s Katherine Hepburn impression is in full swing as the girl coos over Tommy with synonymous maturity (but much more restraint comparatively)—the Hepburn routine, as frequently as it’s used, never seems to get tiresome. There is a genuine excitement in its usage, as though Avery was counting down the days until he could use the gag again. Additionally, said appearances of the joke are spread out enough through his filmography to remain novel. His self indulgence stems from an overwhelming innocence, and is much more harmless than it is irksome.

Here, Avery channels a previous Hepburn shtick; more specifically, Elvia Allman’s performance in Little Red Walking Hood. The girl’s addendum of “…and this is so silly, don’t you think?” is a direct cue from the former (“Rather childish and a bit silly, don’t you think?”). Both instances are funny, as they embrace the pompousness innate in Hepburn impressions and prove to be an effective juxtaposition for the deliberately lax, lighthearted atmosphere, but Avery has mastered giving the punchline some weight through slight directorial maneuvers. Most notably, the camera suddenly trucking in once the girl speaks to the audience. Our attention is commanded, the break in character seems more sharp, and it feels like even the technicalities—camera, stating, etc.—all come to a halt to break character with her.

We thus leave the two alone as George Washington’s birthday is the next point of focus. The holiday is an example of one of the more laughably menial selections in the cartoon—it wasn’t chosen because Avery just happened to have a burning passion for George Washington. Rather, it presents ample opportunity for burlesque; who can pass up the opportunity to draw a young Washington with a powdered wig?

The story about Washington and the cherry tree is where Avery’s comedic priorities lie. Or, more specifically, the consequences of such. No time is wasted with the exposition. In fact, the obedience and brevity in which Washington chops the tree down (paired with the innate facetiousness of his powdered wig) is practically a joke in itself through how routine it feels.

While the simmering confrontation between George and his father is where the sequence is most dedicated, there is some fun regarding the puniness of the tree. Despite being a glorified twig, its collapse is given the same severity as a giant redwood crashing in a forest. Ear shattering noises of destruction that linger for a few seconds is the most notable aspect, but George’s manly declaration of “TIMMMMMBEEEEEERRR!” aids in embracing the scenario’s facetiousness.

Casting Bob McKimson to animate George’s father (and, soon after, George) indicates a priority on character acting and believability. There will be no giant, wild takes or goofy hysterics—McKimson could animate those just as competently, but with rich, sculpted draftsmanship being a specialty, a subconscious indication arises that Avery is going to play this one cool. Exuberance of the tree falling was his fix for lighthearted antics.

Save for another coy acknowledgment of one powdered wig.

McKimson needs to lengthy introduction of his inimitable skill as an animator, but nevertheless deserves reminding. George and his father are executed at different intervals—father animated on twos, George on ones—to illustrate a natural disparity in demeanor. George, a plucky young kid, comes to a fast, skidding halt in front of his slow, lumbering, intimidating father.

“Didst thou chop down yon cherry tree? Didst thou?” Old English syntax from his father is intended to be just as cooly flippant as it is imposing. Stalling’s noble musical accompaniment indicates a heartwarming lesson is to be learned and internalized; a genuine application of good morals.

We should and do know better than to expect that from a Tex Avery cartoon. Avery himself channels that same statement through George, who, instead of reciting the most iconic confession that had never actually come out of his mouth, rebuts with purposefully antithetical colloquialisms (with a formal finish): “Mmmm… couldst be!”

Next is Arbor Day—another comparatively “menial” holiday. Despite the declaration that the holiday was on the 19th of March, it was actually held on April 26th in 1940. It likely isn’t a massive oversight or matter of sheer oblivion; rather, some finagling on Avery’s part to gauge which holidays could flow together best. Easter follows this one, which is a comparatively big holiday—Arbor Day is more low key, as is Washington’s birthday. The two are essentially a part of the same mental tangent, displaying Avery’s admirable tendency to view how the entire cartoon flows together, rather than just milking each individual detail.

In any case, the punchline for the tree holiday is as low key as the holiday itself. At least, low key for viewers acquainted with Avery’s work; one man struggles to get the approval of an off-screen assistant in where to position his new tree. The instructions are purposefully redundant (“Over to the left… little more… down… up a little, now… over to your right… just a bit… more… more…”) to stress the unintentional headache posed by this off-screen entity.

Who, of course, is a dog implied to be readying his bladder. Though not one of the short’s more riotous jokes, it stems from that same earnest indulgence as the Katherine Hepburn imitations; it’s difficult to get frustrated at its repeated usage. It’s a mere fact of life for Avery’s cartoons.

Momentum is constant as we move swiftly along. The arrival of Easter heralds the arrival of Easter Bunnies; Avery’s subversive tendencies can be as subtle as they are wild. That is, instead of depicting a jolly, anthropomorphized Easter Bunny spreading hayseed joy to children everywhere, Avery embraces the literalism of the name. The Easter Bunny is just a regular old bunny. With his diminutive size, hiding eggs seems to be a chore in itself.

In spite of the flat staging, Avery simulates depth where possible. A notch is cut into the tall grasses in the foreground, which provides room for the rabbit to interact with those environments and appear to be living in the space he occupies. Extremely intricate and dimensional staging is not the priority for this particular scene. Regardless, little decisions to “dress it up” like so can aid in maintaining visual interest and believability.

Such a straightforward demonstration invites room for an antithesis. In comes a hungry, devious fox with nefarious intentions—a much more drastic shift against the domesticity of the rabbit. As is usually the case in such cases, Warren’s narration turns stolid, tense, careful word choices seeking to increase the threat of the fox.

Those familiar with Avery’s work know to expect an immediate subversion. Rather than having the fox collapse in a fit of remorseful sobs (as his bobcat counterpart does in Cross Country Detours), he indulges in the polar opposite: mimicking the unrestrained exuberance of a breathless little kid and asking for an Easter egg.

The shift is plenty amusing on its own—Blanc’s vocal performance and the clear, concise crescendo leading to the punchline garner the desired laughs. However, it is also an incredibly important punchline added to Avery’s legacy: such marks the first loving lampoon of John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men—specifically, the character of Lennie.

Lennie Small is to Tex Avery as peanut butter is to jelly. The release of the 1939 film adaptation was one of the greatest jumpstarts to Avery’s career. Audiences pitied and were moved by Lon Chaney Jr.‘s performance of Lennie. Avery was moved, too—in the opposite direction. Seeking copious amounts of comedic potential in Chaney’s performance, any dim witted star of Avery’s cartoons; whether explicitly named Lennie, as in Lonesome Lennie, or deliberately starring as the role of Lennie as the impending Of Fox and Hounds establishes, or as minor as an incidental bit player, their mannerisms would more often than not be based off of Chaney’s.

The lampoon isn’t as obtuse as it is in something like Of Fox and Hounds; the fox reads as a gleeful, overzealous dope more than an explicit caricature of Chaney’s Lennie. Regardless, seeing that Of Fox and Hounds is ever nearing in Avery’s line of filmography, it doesn’t seem like a stretch to deduce that the idea was being mulled about here.

In any case, the Easter Bunny—rightfully terrified—forks over his offerings. An innocently nonplussed stare from the fox at the camera is a solid, genuine capper. His childish, earnest acting continues to be a great antithesis to his threatening, imposing introduction; the shift is successful and palpable.Matching forth, April ushers in April Fool’s day. Cleverly so, Avery embraced his love of subversion by having the joke be on us. That is, in the words of the narrator, “there ain’t no picture!”

Sincerity of Warren’s narration sells the gag completely. While breaching the flow of the cartoon is a creative directing and writing choice, a blank screen isn’t particularly hilarious. Warren’s narration as he revels in successfully fooling his audience, breaking the stolid act for a much more naturalistic lapse in professionalism, is.

Avery secures that a laugh is garnered from such a risk through the old “The Management” bit. While not necessarily old here, having first been flaunted in Johnny Smith and Poker-Huntas, the manual sliding of the card into the projector directly mirrors many synonymous instances in his cartoons at MGM. Continuing comparisons to his tenure at MGM, where his best work was arguably performed, is an indicator all in itself of his directorial growth.

Such a disingenuous tangent requires a subsequent appeal to pathos, and no holiday is better suited than the mush inherent in the phrase “Mother’s Day”.

Our mother of choice is a kindly old woman with an acute case of rotoscoping; while it looks odd on its own, the rigidity of the animation constructs an effective contrast against the uncanny specificity of her son’s design. Who, thanks to Warren’s narration, is given a grand entry, the two having been separated for 22 years providing ample room for heartwarming antics. A long, gradual pan to the door, audio cues from sound effects, and a laden pause at the door (comedically puny window dutifully noted) succeed in concocting an anticipatory crescendo.

All of this careful orchestration gives way to a purposefully apathetic reunion on both sides. Having the “long lost” son be indifferent is somewhat of a given, but would be a bit too heartless on its own. Enabling Ma to share his detachment is much more amusing, as it deliberately betrays Warren’s hyper narration that paints her in a sympathetic light. Warren himself is the only one excited at the prospect of the reunion: a few hellos and goodbyes are exchanged from each end, and that is that. Even the music is sardonic, empty, apathetic.

In comes June, whose calendar card marks a slight breach of decorum. Unlike the other holidays, there is no red typeface listing out the specific subject of our attention—such is thanks to the holiday covering a general idea rather than a specific day. In other words (from Warren himself), the graduation month for students “throughout the land.”

Virgil Ross breathes life into the dean and his select graduate, “McGee”; Tex Avery likewise supplied the voice of the dean in question. Ross’ acting is dimensional, genuine, yet maintains enough visual flourishes to sustain interest and appeal. Likewise with the tilts from both the body and head that encourage a sincere weight to the movements.

“You are now equipped to take your place in society!” Avery’s deliveries are determined, booming, but maintain a gregarious warmth that enables him to remain a ham—particularly with his sendoff of “Go-o-o-o-o-o-d luck, McGee!”

McGee’s purposive march out of the college and into his new life is just as amusing. He is more reminiscent of a toddler playing dress up than a genuine graduate—a lack of visible reactions solidifies as such.

Convolution of the gag—Avery’s pompous yet sincere voice acting, length of the graduate’s marching off the stage and into the street, the regality of the transition—renders it more intriguing by default. Through such preparation, the audience hungers to see where or what it will result in. Therefore, a heavily ironic and anticlimactic punchline is in order.

A punchline that is just as true as it is today was it was in 1940. Being literally shoved into the breadline is one thing; bumping into the dean, who is right in front of him in line (“Take it easy, McGee,”) is another. A solid, effectively ironic resolution supported by its truth, its contrast, and its arduous build up.

Jumping straight from June to October makes for a brief surprise, but is nevertheless confident in it’s time warp. Whether Avery believed the later holidays had more merit, or just didn’t have enough time to include a footnote for something like The Fourth of July, we may never know.

In any case, Halloween piques the audience’s interest more regardless. Johnny Johnsen awes the audience with his tight painting skills and eye for juxtaposition in color; the yellow glow of a jack-o-lantern’s eyes against the cold, navy sky is striking and proud. Likewise with the eggshell white of the full moon, cold in its vast emptiness yet warm in its reassurance of light.

Introduction of “the old witch” heralds a leftover from the Depression era that is lost on viewers today. Jay Sabicer leaves a particularly poignant explanation in the comments of Stephen Hartley’s blog, who explains it with much more grace and thoroughness than I ever could:

“Dollar Days were a Depression-era promotion with many hard-hit business districts. A dollar was a substantial amount of money, back then, for many, it was half-a-day's wages. But during dollar days, many items that were usually sold for multiples of $1 were on sale. Today's equivalent would be a Grand Opening event at a 'Dollar' store, where the first 100 visitors could get a big-screen TV or other high-ticket items for a dollar. People would camp out in front of the store, sometimes for days before, to satisfy there need for material possessions they normally could not afford to have.”

Thanksgiving having two respective dates is yet another holdover of the Depression era. Franklin Delano Roosevelt made a motion to push Thanksgiving a week earlier in order to extend the holiday shopping season; Republicans in particular were not satisfied with the change, thus providing the explanation as to why the Democrats have it a week earlier here. The date for the holiday was nevertheless regularized in 1941.

Glimpses of an idyllic family preparing to engage in their turkey dinner summons more rotoscoping that feels somewhat out of place. Not egregiously so, as the animation is handled with enough consciousness to be serviceable, but incongruous when understanding Avery’s usual standards for humans. Such seems to be why the family is rotoscoped to begin with; a more convincing display of bucolic grace than what Avery’s natural sense of caricature would allow.

Most importantly, it enables the turkey—praying at the head of the table—to shine in contrast, accentuating the quizzicality of his appearance. A lack of questioning from the family regarding his inclusion secures the confidence of the set-up.

In fact, the only inkling of visible confusion (coming from gramps in the corner) arrives only after the turkey comes to his senses. Blanc’s dubious declaration of “Turkey? WHAT AM I SAYING?” is packed with signature Blanc-ian charm and earnest as he directs his horror to the audience. Wide eyed expressions and loose limbed hysterics as he scrambles out of his chair all arrive as a strong antithesis intended by the solid human designs.

No comments:

Post a Comment