Release Date: November 2nd, 1940

Series: Looney Tunes

Director: Bob Clampett

Story: Warren Foster

Animation: Vive Risto

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Porky, Cat, Bird, Fish), Bob Clampett (Vocal effects)

(You may view the cartoon here!)

As the cartoons of 1940 slowly crawl to a close, The Sour Puss marks the last animation credit for animator Dave Hoffman. Previously mentioned in the analysis of Pied Piper Porky, from which he gained his first animation credit, very little is known about his whereabouts. He doesn’t seem to have any surviving credits to his name after this one. It’s not to say that this was his last cartoon, as the credits were enacted on a rotating system with very little rhyme or reason, but it does indeed seem to be one of his last.

In any case, with the topic of change in mind, the short—similarly to Prehistoric Porky—recaptures the nostalgia of Clampett’s earliest shorts and influences. A heavy comic strip influence is felt through its share of graphic touches, as well as an unabashed embrace of wild, creative action beyond the funny noises emanated by a character (which there is plenty of.) Though maintaining some restrains of the then-current Clampett’s filmography, the short does make an effort to dig itself out of a coffin of mediocrity.

The premise itself is seemingly innocuous: Porky and his cat have plans to go fishing, which are quickly thwarted by a restless, screwball catch.

For a cartoon that gets to be as wild as it is, its opening is deceptively domestic. Such is the point—the docility offers a clear reference of juxtaposition, enabling the impending hysteria to seem more raucous. Indeed, there is nothing more domestic than Porky reading the newspaper in his rocking chair, feline companion faithfully by his side, twittering of a bird in a bird cage to underscore the harmony between the quasi-animal and his pet animals. Staging of the composition is refreshing and welcome in its awareness; foreground objects such as a shelf and some plants, a banister, and even the staircase itself form a clear frame around what little action there is.

Dissolving into a close-up of Porky heralds a shot that is a little too bloated for its own good; 7 seconds of rocking isn’t necessary to get the point. On the other hand, the length aids in instilling the cozy ambience sought after. Prominent sound effects of the chair creaking become a natural fixture of the composition, complimenting Carl Stalling’s sleepy accompaniment of “Where Was I?”—the audience is naturally lulled into a contented stupor through the soft monotony.

Likewise, another dissolve to the cat narrowly avoiding getting his tail crushed with each cycle of the rocker politely elbows the viewer, reminding them that yes, this is supposed to be a funny cartoon, no, it isn’t just Porky rocking for 7 minutes straight. Timing on the cat’s tail is light, airy, realistic in its carefree swishing. Such allows the gag of it narrowly avoiding getting crushes to read more believably and naturally. Having the rocking chair press firmly against the floor with a subtle antic not only gives the motion more weight and anchors its rhythm, but introduces a more tangible threat to the cat’s tail. Having the rockers physically fold against its own weight against the ground means bad news for anything that happens to get caught underneath.

Synonymous to many others of the time, this short isn’t exempt from the Clampettian tendency to bloat out the introduction through pans, still shots, or otherwise low risk pieces of animation, such as the repeating cycles seen here. While a cut to Porky turning the page of the newspaper before indulging in more still shots isn’t necessarily a clever tactic to pull the wool over the audience’s eyes, it does succeed in giving some sort of life and motion to the flow. At the very least, more than what would be present if they had just cut to the next still shot entirely.

A curt glance at the front page for the few seconds it’s visible reveal a few nonsensical details: typeface of the headline joyous in its incomprehensibility, a crude drawing of a flower, and another photo that, ever so succinctly, just says “Boo!” Such unabashed juvenility is an endearing contrast to the decidedly more “adult” hobbies of reading newspapers, rocking in rocking chairs, and owning pet cats and birds.

Direct point of view shots from the lens of Porky offers wordplay native to Clampett’s films, as well are tangential, nonsensical details pertaining to the newspaper inside. Namely, a baseball game with a final score of 899 and 418. Most intriguing from a technical angle, however, is the background—though difficult to discern through a conscious lack of detail, the painting can be seen moving up and down behind the newspaper overlay. A keen attention to detail that elevates a standard newspaper shot (something that frequents many Clampett cartoons) into something more intimate and immersive.

Comparisons to Prehistoric Porky are drawn through similarities in exposition. That is, the story of the cartoon is largely dictated by Porky being influenced from outside sources. In this case, a headline about fishing season opening the next day.

His “Ehh-f-ehh-fishing season? Oh eh-buh-bih-bih-boy!” isn’t necessarily a heartfelt declaration of his passions—very little alludes to him being a passionate fisherman. We don’t open to a series of hints regarding his passion, no matter how newfound it is; no Porky’s Duck Hunt-esque introduction of him studying various fishing rods or reading fishing magazines. With the sheer domesticity of the opening minute, such a comparatively “sporty” activity seems like the last thing on his radar.

It seems safe to say that his zealous attitude stems from the idea of fishing. Realistically, he may not care about fishing one way or another. Yet, if it’s important enough to warrant an article in the paper, then that indicates a trend, and that many people are anticipating the opening of the season. Eager in his conformity, Porky just assumes that it’s the thing to do.

Which is why his attempts to impress with his fishing gear read more as a glorified game of dress-up. Childlike, exuberant energy is on the forefront. Dedicating time to his swinging out of frame when grabbing the closet door touches upon this—he’s so excited that he’s become an uncontrollable force and has to steady himself before proceeding. Sincerity in his character and his motives—even if his passion for fishing does not seem to be in unabashed earnest itself—continues to cement itself as a strong force of appeal.

A standard double bounce walk as he proceeds forth capitalizes on the aforementioned juvenility; the comparatively mechanical execution of the walk, as it often does, seems to exaggerate its endearing absurdity further than actually hinder it.

Porky’s conversation with his cat—aptly named Pussy—brings an interesting discrepancy between animation. From both draftsmanship to motion and timing on both, it almost appears as though two separate animators split the scene: one for Porky, one for the cat. Though Clampett was known to switch animators without warning in the middle of a scene, even that seems a bit random for him.

In any case, the cat both moves, looks, and acts like John Carey’s handiwork, whereas Porky does not. Carey undeniably does the impending close-up of the cat; it seems that if he were to have animated the cat in the scene before, the two scenes would hook up more tightly. Instead, the first scene ends with the cat’s firmly established, sleepy grin—the second one starts from the beginning in that regard. It’s more likely that the animator was instead incredibly loyal to Carey’s layouts of the cat, and potentially could have been directed to mimic his animation style.

In the long run, this is all speculation and nothing more. Regardless as to whose hand is responsible, drawings of the cat are very well executed and—most importantly—very funny. His languid, stupor-like movements are a stark antithesis to Porky’s boundless energy. Through such a juxtaposition, Porky is made to seem even more innocent and juvenile, allowing his excitement at the joys of fishing to be even more potent.

Quizzing the cat on what they’re going to have for dinner (rather than declaring the answer outright) proves this. A close-up of the cat guessing opens the door for some gorgeous John Carey drawings; he hits a wide range through his acting. Solid draftsmanship, intricate perspective, charismatic drawings, funny drawings, believable commitment to visual gags.

Porky prodding the cat to guess (and depriving him from the dignity of an answer) spawns an amusing visual of the cat walking, clucking—whose clucks are provided by Bob Clampett himself, often taking any chicken roles in his cartoons through his proficiency in verbal sound effects—and behaving like a chicken. It isn’t necessarily the pantomime that’s funny, but the sheer commitment to it. The bit is most successful thanks to Carey’s strength in his drawings—the cat’s muzzle turns pointed, his tail droops to mimic tail feathers, his paws extend into points to imitate wings. He isn’t so much acting like a chicken as he is transforming into one. Or, at the very least, a reasonable facsimile. Anyone can draw a cat clucking like a chicken, but only few can embrace it so wholeheartedly and make something so absurd so believable in its commitment.

Solid acting extends beyond transitions to different animal species; the cat appears genuinely hopeful at his impression, bracing for an affirmative answer. A no from Porky likewise spawns a viscerally humorous and cloying display of disappointment. The cat is more akin to a mime than an actual house cat. Sheer exaggeration of his acting, no matter how insincere it may seem on the outside (with a conversely sincere commitment to said insincerity), evokes empathy from the audience. Strong drawings and animation contribute greatly to the cause.

Norm McCabe, on the other hand, is bestowed with the dignity of animating one of the most liberal distortions Porky has ever been subject to. Due to his natural empathy and role as a comparatively subdued straight man—still eccentric to feel at home with his cohorts, yet not as eccentric as others—it’s rare for him to engage in the same full-body distortions that more emotional and hysterical characters are subject to. In many cases, it’s a missed opportunity. Frank Tashlin once lamented that his disdain for working with the character partly stemmed from an inability to do anything with his body.

Here, Norm McCabe, Bob Clampett, and Warren Foster dismiss such an idea by having Porky obey the same principles as his cat. Just as the cat transformed into a quasi-chicken, Porky transforms into a quasi-fish. Actually contorting his body into such a form with no other outlying commentary other than the drawing itself is much more funny through its dedication and blind trust than him merely putting his hands to the sides of his face, mimicking the flowing motion of gills. Likewise, his adamancy on the correct answer and unnecessary defensiveness (“It’s eh-eh-fish! Fee-eh-fish! Yee-you know… fish!”) injects an enigmatic genuineness into such a ridiculous concept and drawing. The drawing itself is plenty humorous on its own, but thrives given the urgency in Porky’s argument. There’s absolutely no reason for him to get so defensive over a guessing game on what’s for dinner—that his cat even responds is a miracle in itself.

Recycling a pose from Porky’s Poor Fish segues into a display of joyous histrionics from the cat. Whooping, cartwheeling, sliding, and other displays of ecstasy arise comparisons to Daffy’s own screwball performance pioneered in Porky’s Duck Hunt. After all, it was Bob Clampett who animated the initial exit. While it may not have the same effect as its first usage—seeing as it represents a cornerstone of Daffy’s personality established right then—seeing the cat perform synonymous acrobatics indoors instead of outdoors almost makes the performance seem more wild. Domesticity of the house provides a juxtaposition to the wild antics.

A handful of reaction shots from Porky’s pet bird (who proves to have a purpose other than ambience) ground the action. Such a snapshot both helps and hinders; helps, in that it again provides an antithesis to the comparatively more “normal” denizens of the cartoon who find the hysterics absurd, allowing them to feel even more powerful and absurd. Hindering, in that such a reaction shot elicits a commentary of “get a load of this guy”—while likely unintentional, such a move inadvertently communicates a lack of commitment and confidence. It’s a riskier move to play the histrionics straight with no outside reactions at all; that in itself provides a sort of wry, ironic commentary that gives the cat full permission to the spotlight. The histrionics in Duck Hunt are so successful because there are no outside reaction shots informing us how to interpret the action. It merely speaks for itself, and is much stronger that way.

In any case, a glimpse of the bird is necessary. His appearance telegraphs an upcoming gag; or, more accurately, a reaction to said gag. So enraptured in his blind ecstasy at the prospect of fish, the cat fishes a mouse out of its hole to give him a kiss.

While a cat cartwheeling around the house can be pardoned, such a blatant dismantling of adversity is the final straw. A “Well!” in the vain of Jack Benny establishes our canary as a harborer of sophistication—he may be even more sophisticated then the cat and Porky. “Now I’ve seen everything!”

Cartoon history is ruthlessly established as the bird, ever matter-of-factly, unearths a pistol and shoots himself. Suicide gags aren’t exactly new to these cartoons—other shorts have had storylines constructed around it, such as Porky’s Romance or The Good Egg, whereas Cross Country Detours does prove to be a worthy predecessor in its shock value. Yet, this particular instance is worthy of expatiation, seeing as many suicide gags that would arise in the following cartoons obey this exact format. A reaction to the camera, an utterance of “Now I’ve seen everything”, and lights out. Unsurprisingly, Bob Clampett was one who perpetrated this format the most—especially as his craving for shock value grew. Any person who’s laughed at the Peter Lorre fish in Horton Hatches the Egg, engaging in the same ritual, can owe that to this cartoon.

Such egregiousness enables the comparatively more endearing footnote to garner humor just through the sheer contrast in tone. Coming back down from his rapture, the cat rubs contentedly against the legs of his owner. Porky’s vacant yet earnest grin is as funny as it is charming. Charming in that it bestows more sincerity to the end of a wild, raucous intermission, again enabling a tangible contrast. Funny, in that it indicates total lack of regard for what just happened. Instead of mourning the loss of his pet bird or trying to talk the cat down from his fit, he seems perfectly contented. Visual and emotional emphasis is much more on the cat, but Porky’s reaction doesn’t feel rooted in negligence with the character in terms of how to direct him. Making him react positively seems to be a conscious move that ensures the note they end on is an effective contrast to the brashness prior and earnest.

As previously mentioned in the introduction, this particular cartoon adopts a handful of graphically minded touches that are most reminiscent of Clampett’s earliest cartoons. His comic influence would last throughout his entire filmography—manifesting only in different forms—yet haven’t been as obtuse and unabashed as they were with his first stretch of cartoons. A title card transitioning between scenes mimics both a written comic influence and a silent film. Thus, the viewer id reacquainted with animation’s many root forms.

Delegating focus to Porky settling in for the night, telling his cat “get right t’ sleep,” ushers yet another offering of cozy ambience. In this case, the moonlight streaming in from the open window. A clear spotlight engulfs Porky, naturally directing the audience’s eye—it likewise demonstrates a palpable difference in values and lighting that make the settings feel more dimensional and interactive.

More comic tendencies reminiscent of early Clampett films (such as Porky’s Hero Agency and Porky’s Poppa) manifest through a thought bubble as Porky begins to count sheep. It’s a relatively straightforward scene—a “ff-four an’ a half” prompts a baby ewe to hop over the fence instead of a full-grown alternative (with a hollow plunking sound effect from Treg Brown giving it more mischievous emphasis), but is otherwise obedient.

Blanc’s deliveries, as always, succinctly meet the scene’s contextual needs; his tone eventually growing softer as Porky drifts off to sleep is again believable and organic. Such was an issue that he struggled with in Porky’s Badtime Story, and understandably so—it was still one of his first cartoons as Porky, after all. Many deliveries felt unnecessarily perky, loud or brash in the scenes where he is struggling to sleep, so this scene (and the short’s remake, Tick Tock Tuckered, which does rectify said issues) offers a more tangible look at his vocal improvement in just three years.

Eventually, the camera leaves Porky alone as it travels to the other half of the bedroom. Versatility with the camera department has grown in the past year or two—camera shakes, gradual easing in and out, complicated pans, and so on have all been achieved that were a monumental task beforehand. With this tightening grip on the technology, more room for experimentation is enabled. Likewise, the camera is given a voice of its own.

Here, as the camera settles on the cat (sleeping in Porky’s dresser drawers with a pillow and sheets rather than at his feet or in a cat bed, as it’s a funnier alternative through its convolution), a slight bounce reverberates before it anchors into place. Such a detail seems more purposeful than a mere accident—that little aftershock maintains the vestiges of lingering energy to breathe more life into the scene and subliminally inform the audience as to the tone that lies ahead. We don’t want them to be lulled to sleep.

That’s where the cat comes in. Porky’s straightforward routine is revealed to serve as an antithesis to the cat’s rendition of counting sheep—or, in this case, counting fish. Through the slurred vocal deliveries mimicking a cat’s meow to the equally whiny musical accompaniment, he serves as a somewhat more insincere contrast. And quite successfully, too.

John Carey animating his close-up provides ample opportunity for tight construction regarding both the cat and the fish; likewise, water effects as the fish splash into the pond are anchored in a stronger sense of purpose than what would be present with other animators. Carey’s versatile continues to become more and more valuable of an asset.

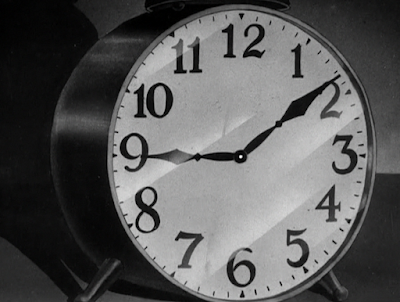

A close-up on a time lapse indicates that his methods of getting to sleep aren’t as successful as Porky’s. Though a return to a much more haggard looking cat doesn’t offer animation that is nearly as tight or as controlled as Carey’s, a number of factors nevertheless savor the punchline of his restlessness: primarily the twisted, knotted sheets indicating a struggle and the numbers he’s manages to hit in the past few hours (“Nine hundred an’ ninety thousand… nine hundred an’ ninety nine… one million.”) No thought bubble resides over his head as it did earlier—the viewer’s attention is directed solely to his comedically convoluted struggle.

Sleeping pills are in convenient access, which the cat concedes to. Close up of said pills reveals the ever-punny slogan “take ‘dese and doze”—Clampett would reuse the same tagline in The Big Snooze, which, worth mentioning, is the last cartoon he directed before his departure from the studio.

Here, the tagline serves more accurately as an afterthought. The true point of interest lies in the contents of the bottle; not pills, but a mallet. Such a nonchalant execution as the cat contentedly whacks himself over the head and submits to a stupor is comparable to Tex Avery’s current prioritization of coolheaded absurdity. Between the wordplay on the bottle and the sheer mischief of the resolution, the gag is very much in Clampett’s territory—comparing this to a somewhat synonymous scene in, say, The Daffy Doc nevertheless yields a growing control in his execution.

With the first act firmly put to bed, the ushering in of the second half is initiated through yet another transitionary title card. Such an invitation to a new day has firmer roots in Clampett’s comic influence. At the age of 12, a cover page he drew himself for The Junior Times (a division of The Los Angeles Times) depicts the antics of a cat getting into hijinks around the neighborhood. One of the panels for the comic marks a similar transition, also encouraged through phrasing of “then came the dawn”. It was this comic that got him a part-time job at The Los Angeles Examiner, working in the art department—the rest snowballed into history.

It isn’t to say that Clampett directly had this very comic on his mind when directing this cartoon some 15 years later, but does demonstrate—if even on a subconscious level—how am much of his creative influence is rooted in comics. The title card is even more akin to that of a silent film, as mentioned with the previous card, but both are nevertheless products of Clampett’s core influences. This specific sort of self indulgence has been sorely missed in his cartoons of late; knowing the relevance behind such phraseology transforms a seemingly out of character transition for these cartoons into one that is endearing.

Just as promised, we find Porky with a pole proudly in his hand. Contented vacancy on his face is amusing—it’s purposefully deceptive. Hardly moving, only sparing a blink as Stalling engages in a perky score of “All This and Heaven Too” tricks the audience into thinking they’re going to spend the next three minutes in a glazed stupor. Surely Porky fishing for that much time can’t be interesting. So much of the sport itself involves waiting… and waiting… and waiting. What sort of a failure of a cartoon is this?

That’s why the camera pans directly over to his cat. Of course he’d bring his cat fishing with him. A string tied dutifully to his tail cements that he too has an intent to fish, not keep guard or company. Seeing as the audience has grown accustomed—and will continue to do so—to Porky’s rotating army of dogs accompanying on his misadventures, a cat assuming the role of a dog is an effective subversion. An eccentric one at that, but executed with an unquestioning innocence on Porky’s behalf that makes it even more effective through such nonchalance.

Cutting to a close-up of the water invites a fin to cut through the waters, indicating that this is a short with some action to be had after all.

Especially when said fish leaps into the air. Another close-up reveals the specimen to be a flying fish, taken to a degree of literality—real flying fish can soar out of the water and glide for a period of time. Here, the fish is nearly indistinguishable from a bird through the frantic flapping of its fins. Offering a sculpted, realistic glance at its construction allows the dissonance to hit harder; a cute, screwball fish is to be expected doing screwball antics. A regular, dead eyed fish doing the same antics is funny through its routine absurdity.

Porky’s cat notices the fish before Porky himself, spurring incomprehensible noises of raw ecstasy. A declaration of “Gosh—it’s a flying fish!” from Porky is somewhat unnecessary, but that is rooted mainly in the shot it accompanies: an up angle of the fish circling around the cat’s head. It’s a nice shot, with the angle making the fish seem to be even higher in the air, its circling boasting a dimensional grasp of perspective. Nevertheless, the shot itself doesn’t seem to fit as comfortably into the overall flow and sequence as others.

It does, in any case, lead into a simmering punchline. It serves as an extension of a gag first scene in Porky’s Hotel, and would be reprised in its current format in A Coy Decoy; the audience is met with a shot of the cat tracking the fish above his head. Instead of moving his head around, his pupils merely rotate around in his eyes, briefly skimming past the back of his head and so forth. It seems relatively innocuous nowadays, but succeeds through a rather meticulous handle on timing. A phantom image of the pupils traveling around the backs of his eyes can be achieved only through a convincing rhythm in the timing—not too fast, not too slow, not too overzealous. It should be convincing enough to account for the fish off-screen, which is the case.

John Carey continually asserts himself as the MVP of the short through dimensional construction and charismatic character acting. A thirty second long stretch of footage, spanning from the cat stalking the fish to actually swiping it out of the air and ogling at it in his paws, demonstrates a barrage of his strengths; his work has enough believability and realism rooted in its movement and dimension to ground it down to earth, but maintains a joyful looseness and dynamism that keeps it energetic and flighty.

The cat engaging in the finger-pantomime routine that has largely come to be associated with Bugs Bunny is particularly impressive through its continuing flow, the cat mimicking the fish’s own rotations above his head. Stalling’s music score matches the airiness of the action, bestowing a permanence on the gag that makes it more tangible and funny through its conviction.

Timing on a close-up of the cat eyeballing his dinner seems a bit odd at first glance; spacing between the drawings is relatively even, making for a somewhat glacial effect that is disconcerting in its smoothness. It isn’t necessarily a detriment—Carey’s tight, meticulous drawings are given an appropriate spotlight as a result, allowing the viewer to chew on the intricate perspective and solidity. Stakes are lowered through the innate nonchalance of a close-up; even spacing and timing would be a bigger issue if the scene begged an abundance of action.

Likewise, such stillness and animated domesticity is all a black red herring. A firm, palpable juxtaposition is established between tones, enabling the fish that comes to life in his hand and honks the cat’s nose to seem even more energetic, limber, and startling in comparison.

If there is anyone who has the right to steal Daffy’s hysterical water ballet in Porky’s Duck Hunt, it’s Clampett himself—he did animate it, after all. Indeed, the fish transforms into a sort of Daffy Lite as he cavorts, flips, walks across the water and guffaws insanely. Considering he had a more solid idea of what made screwball characters so appealing, Clampett’s cribbing isn’t as insufferable as Ben Hardaway’s attempts to do the same. Regardless, those accustomed with Daffy’s routine are able to see through the act, lessening the impact considerably. It was trusted that the audience would be unfamiliar with the routine at the time of the short’s release.

An additional close-up of the cat suffers from Carey-itis: John Carey’s animation being so solid that other shots by different animators suffer and look worse than they really are in comparison. The drawing isn’t necessarily bad; the cat contemptuously cocking his eye is an amusing character detail that humanizes him and his emotions, which has been a main selling point of the cartoon. Regardless, the drawing style looks much different than Carey’s, forming some inconsistencies between shots.

Dedicating a beat to the cat stuffing his muzzle in the water suffers from the same loose draftsmanship. Timing on the animation is somewhat glacial, bloated; he doesn’t exude the haughty intimidation that is intended. In any case, the fish’s back and forth twirls and jumps are rhythmic and dynamic, successfully limber. Water effects as he splashed into the water are likewise serviceable and much less crude than the water effects seen in a short such as Porky’s Duck Hunt.

Angling the camera from the fish’s point of view not only encourages clarity for the eclipsing gag, but makes it sympathetic—if such a term could be used for such a brainless heckler—towards the fish. More accurately, it is less sympathetic to the cat; a fine objective, seeing as the audience doesn’t want to feel remorseful as the fish uses the cat’s nose as a punching bag. Placing more physical focus on the fish enables the gag to register as something that should be laughed at, rather as another means of pity for the cat.

It takes a few seconds for the gag to even begin, which is somewhat awkward in its execution. Those seconds do have a purpose—the cat rolls his eyes around until he focuses on the fish, who then initiates his boxing spree. However, as a consequence of the water effects concealing much of the cat’s face (as well as the position of the camera commanding the attention of the fish), the action is largely lost in translation.

More cavorts soon segue into a bass line, courtesy of the cat’s tail. Remarkably, the sound of the bass remains obedient to Stalling’s ongoing arrangement of “All in Favor, Say ‘Aye’”—the orchestrations themselves shy away to enunciate the bass, strengthening the gag and its focus, but not a beat is lost regarding the ongoing rhythm. Reverberations on the cat’s tail are affectionately crude, lines feeling a bit too loose and self conscious. Nevertheless, conveying the after image effects both ground the movement in realistic physics and embrace a visual caricature that boldens the action.

Vagueness on the fish’s actions lessen his credibility as a sufficient follower of Daffy’s philosophy; his swinging idly in the air as he makes fun of the cat is enough to establish his role of an insane, physics defying pest, but the same sort of natural execution seen in Daffy’s introduction is not present.

It’s nevertheless sufficient enough to goad the cat into propelling himself into a rock. Impact on the rock as it squashed against itself is more akin to an aimless, gelatinous mass rather than an object reacting against a physical force—it seems to jiggle in place rather than bend against its own weight. Regardless, such elasticity is a welcome touch to begin with; it makes the cat being hit seem less painful, as well as inject a mischievous energy into even the background environments of the cartoon.

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment