Release Date: November 9th, 1940

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Tex Avery

Story: Dave Monahan

Animation: Virgil Ross

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Robert C. Bruce (Narrator, Tomcat), Mel Blanc (Fawn, Bird, Bobcat, Packrat, Alligator, Pig, Termite, Coyote, Camel, Dog), Margaret Hill-Talbot (Baby Bird), [presumably] Marion Darlington (Whistling)

(You may view the cartoon here or on HBO Max!)

The third consecutive spot gag cartoon from Tex Avery, Wacky Wildlife also happens to be the last one of the year. Avery himself has more travelogues behind him than those that are ahead; the remainder of his time at Warner’s—which unfortunately isn’t very much—would see him prioritizing a return to character driven endeavors and overarching storylines. Even if the storylines themselves are not exactly rife with substance.

Despite not boasting much within the short that distinguishes it amongst its siblings, Wildlife does nevertheless exhibit Avery’s staggering artistic and directorial growth within the past handful of years. Similar compliments could be paid to the recent slew of Avery-directed spot gag shorts in general, but the evolution is undeniable. Compare a drawing of a fawn in this one to the appearance of a gazelle in The Isle of Pingo Pongo; despite a difference of only two years, the designs and attitudes in each cartoon seem light years apart. It becomes all too easy of a habit to knock Avery for the repetition of such a format. If anything, the monotony provides a clearer basis of comparison for his growth.Content of the short lives up to its name: the antics and activity of wildlife from all around the world are viewed and burlesqued for the enlightenment of the audience.As per tradition, our venture into the animal kingdom is initiated through the expository orations of one Robert C. Bruce. Lofty syntax paired with a gentle musical arrangement from Carl Stalling and the lush painterly work of Johnny Johnsen successfully delude the audience into a false sense of tranquility. A clean, tidy order that is begging to be dismantled and overthrown.

Ripple glass effects on the pond are convincing in their depiction of the breeze forming gentle waves—the introduction of a fawn, however, accentuates its effectiveness through the deer’s reflection in the water. Allowing the ripple glass to distort a still background painting is one thing. Introducing animation into the equation, and that of a reflection, instills a believability and conviction to the atmosphere. Once, the inclusion of ripple glass was a revolutionary effect in itself. Now, Avery and his contemporaries have gotten comfortable enough with the technique that they are willing to introduce motion and meticulous upkeep of animation as a risk. Said risk pays off.

“Daintily, she lowers her head and sips quietly.”

Accustomed viewers of Avery’s filmography can already spot the punchline from a mile away, but that doesn’t make her decidedly un-dainty “sipping” any less funny. Exposition and preparation leading to the gag is much longer and more arduous than the joke itself, which arouses a laugh all on its own. Effectiveness of her lapse in manners can only be achieved through such orchestration and preservation of atmosphere. A drunken, slurred score of “How Dry I Am” likens the doe to a rowdy, bottomless bar drunk rather than a gracious symbol of nature and docility.

Amidst her slurps and splashes, a hiccup is slyly inserted—the censor-approved substitute for a burp. Her display is not impeded by such obedience to the Hays Code; the caricature of the hiccup adds to the whimsicality of the tone. Distortions and strain in her face as she grants the hiccup escape convince the audience that it is intended to be a ruder gesture than what is actually permitted.

Especially with her dainty “Excuse me,” before heading off. Blanc delivers the line in a falsetto, which upholds a coy, disingenuous mischief native to the tone of the joke. Having an actress such as Sara Berner deliver the line would lose some of the hinted comic edge; wry disingenuousness in the characters, not the filmmaking, is the priority.

Avery gets his “cute little creature obliviously enraptured in the clutches of peril” fix out of the way next. This time, the food cycle is between a little bird and a particularly menacing snake. Yet, instead of having the snake creep up on the bird with open fangs, a new element is introduced—hypnosis.

Literal hypnosis, too. The snake makes steely eye contact with the bird; a menagerie of electric spark effects bestows a coy literality to the concept of snakes hypnotizing their prey. Such a caricature of concept gets a laugh from its absurdity, just as it makes the action more clear for the audience to digest. All topped off with a sleepwalking stance of equal visual burlesque.

Rod Scribner tackles a number of the cartoon’s close-up shots; the snake unhinging its jaw to beckon the bird is no exception. Sculpted, dimensional, realistic, Scribner’s draftsmanship brings definition where it’s needed—such as the details in the snake’s mouth—to elevate the threat through realism, but maintains enough additional looseness with other points of acting to remain captivating and dynamic.

Such is the case with the sudden cognizance of the bird. His aside to the audience is directly lifted from Pied Piper Porky, where a mouse breaks out of his own stupor and quips to the audience “If you think I’m going in there, you’re crazy!” The same is true here, with even the mouse’s Rochester-esque dialect adapted to the bird. Similar to the deer and her drinking, the payoff is made more effective through deliberate buildup and a gravity in directing.

Likewise, a direct bookend—the bird resuming his sleepwalking in the opposite direction—encourages coherency and rhythm. The tangent feels like a fully realized segment with a discernible beginning and end, allowing a transition into another idea to feel more organic.

Avery’s next gag is a loose expansion of a somewhat similar visual in A Day at the Zoo; both are united through sentient shadows. Whereas a groundhog’s shadow paced in a separate cage of its own, here, a skunk’s shadow even betrays his physical counterpart. Adjusting the camera to reveal the visual after a few beats instead of immediately cutting to the gag maintains a surprise aspect. The audience is thusly kept engaged through the cause and effect method of filmmaking.

Introduction of a bobcat is, surprisingly, not for the benefit of concocting a contradictory sense of melodrama. Sculpted construction and realism of the bobcat’s design may hint to otherwise, but the jovial, amiable music score in the background proves to be the stronger indicator.

Indeed, the point of the segment is all about amicability. Wordplay between “bobcat” and “tomcat” would prove to be a subconscious influence for one of Chuck Jones’ many running gags later in his career: specifically, the greeting of “Hello, Tom.” “H’lo, Bob!” between the two.It isn’t so much the literal application of the names that is so amusing, but the nonchalance of the exchange. The innate, menacing associations of a bobcat juxtaposed against the comparatively innocuous demeanor of a tomcat renders the pleasantries all the more surprising. Moreover, with Bruce himself voicing the tomcat (and Blanc with the bobcat), the exchange has a thin layer of authenticity that perhaps would not have been as strong if Blanc had voiced both characters.

Moving forward, Wacky Wildlife is yet another deceptively formative cartoon for Avery. A handful of gags touted in this one would be repurposed later on to greater lengths of caricature and streamlining; one such gag is that of a crane walking continuously on one leg.

Slap Happy Lion, often regarded as one of Avery’s best cartoons, would reprise the same gag. Of course, seven years of experience and embrace of directorial identity results in a greater exaggeration and utilization of the gag. Here, the visual in itself is the joke—in Lion, the application of the visual gag is what garners more success. Regardless, that Avery reused the joke at all seems to be a slight indicator of his fondness for it.

“The packrat—an interesting little animal—has a very peculiar trait.” Bruce guides the audience through the behaviors of the packrat and its tendency to consistently replace objects. Animation in the establishing wide shot of the rat is rooted in realism through the timing of its fragmented, tangential, hesitant movements. Thus, the close-up of Rod Scribner’s looser, elastic, and more cuddly appearance marks a shift in tone that braces the audience for a gag.

Said gag goes on for nearly a minute straight. That is, the mouse runs back and forth from either end of the screen, replacing an acorn with an egg, the egg with the acorn, the acorn with the egg, and so forth. The entire point of the sequence is to be as repetitive as possible, hence the mouse’s eventual aside of “Monotonous, isn’t it?” to the audience.

Avery excels at the feeling a little too efficiently, stretching on longer than ever necessary, but is the whole point of the gag. He loved to agonize the viewers and annoy them wherever possible, whether through itch-inducing levels of monotony here or deliberately annoying voices (such as Berneice Hansell’s many long-winded monologues in his earlier films.) The sheer lack of substance feels like a cheater in its transparency to fill time, but, again, is difficult to get truly riled at—such is the whole point of the gag. Stalling’s repetitive xylophone arpeggio sells the purposefully convoluted repetition.

Introduction of an alligator infested swamp ushers our second gag to be reprised in—yet again—Slap Happy Lion. That is, a particularly menacing alligator revealed to be suffering from a case of macrocephaly. Comparisons of both gags yield a stronger sense of unity than difference; both are topped off with a pitiful explanation of “Well, I’ve been sick…” that leaves more questions than answers.

Lion’s spin on the gag follows the rule of trees: two regular alligators making their exit to establish the “control” variant of the gag, and the final topper. Here, Avery milks the menacing, naturalistic atmosphere—tense music, stoic narration, the sheer number of alligators to begin with. Solid draftsmanship and believability of the designs render the gag more triumphant in its juxtaposition. Absurdity is stronger and more potent when an attempt to ground the gag back to earth is made—in this case, preserving the realism of the alligator’s features. It’s only the proportions that are off.

Scribner returns to provide visual accompaniment to Bruce’s next piece of interest: “An interesting study in bird life is this mother scolding her little one.”

There happens to be an intriguing divide in design and animation between the mama and her brood—to coincide with her realistic bird whistles, drawings on mama are more sculpted, realistic, an emphasis on perspective as she tilts her head and communicates entirely through body language. Meanwhile, the design and animation of her child is loose and caricatured; his movements and acting read as more human to coincide with his humility. A certain pathos is bestowed unto him as a result.

Of course, the humanity of his appearance and demeanor is all purposeful. Consciously or otherwise, it prepares the audience for his own, decidedly human rebuttal through both anthropomorphic body language and speech: “Aw, lay off the bird talk, Ma! What’s on your mind?”

Keith Scott cites the voice not as Berneice Hansell, of whom it sounds astonishingly similar to, but to that of Margaret Hill-Talbot. Indeed, the bird's sentience is capped off with the appropriate posing and body language (one hand on his hip, legs crossed).

Spitting off-screen embraces his anarchy and abrasiveness. Now, pathos is shed onto the mother as she gawks helplessly at the camera.

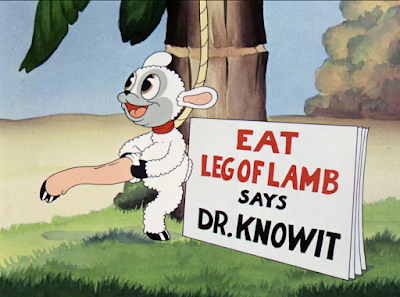

Next, a trip to the sheep ranges of Montana, as illustrated through Bruce’s idyllic narration. Gentleness in Stalling’s musical score and the lushness of Johnsen’s background paintings once again establish an atmosphere ripe for a brazen rebuttal.

Said brazen rebuttal is initiated through comments pertaining to leg of lamb: here, Avery borrows not from himself, but Friz Freleng. A lamb coquettishly displaying its own leg was first seen in 1937’s The Lyin’ Mouse; its usage here has the benefit of much more sculpted, realistic draftsmanship, allowing the juxtaposition to land more effectively. Likewise, the innately sultry implications of “It Had to Be You” in the background make for a nice compliment that wraps the gag all together.

“Common to every farm is the pig,” is the nicest statement out of Bruce’s mouth regarding the mud-bathing swine. His vocal tone grows much more candid and pinched, full of disdain as he calls the pig all sorts of synonyms for “dirty” that he can possibly think of. Between his narrations, his brief role as the tomcat, and the sudden loss of professionalism here, his vocal range is refreshingly flexed and establishes what a versatile talent he is.

Blanc voices the deep, gravely voice of the pig (no stutter in this case) to simulate its grunt. His rebuttal of “Alright, so I ain’t neat,” can also be heard in Freleng’s Porky’s Hired Hand, which could allude to its source being a possible radio reference. Then again, both cartoons credit Dave Monahan as a writer, so it could be nothing more than his own brainchild.

Interestingly, segueing to a spotlight on ducks basking in the swamps of Louisiana is one of the earliest references to WWII in the cartoons. Allusions were certainly present, dating as far back to Bosko’s Picture Show in 1933 being the first cartoon to caricature Hitler, but it wouldn’t be until the U.S. officially entered the war themselves that the references, gags, and propaganda would get so concentrated.

Introduction of the segment is innocuous and docile. Bruce’s tone grows hushed at the arrival of the ducks, inviting the audience to share a discreet sense of awe as they observe. A nondescript hunter, cast entirely in silhouette, introduces an urgency and tangible suspense that keeps the viewer engaged and introduces a pathos to the ducks. All believable in pacing and plight; reflections of the ducks in the water are a great touch, contributing to the believability of the animation and atmosphere.

A gunshot from the hunter prompts the ducks to fly off-screen in various perspectives—save for one. Bruce’s pleas for the duck to fly away go unreciprocated; instead, a rather pompous shake of the head from the mallard indicates purposeful, pompous ignorance.

Such leads to the reveal of an American flag emblazoned on his side. Before the U.S. went into war, ships sent overseas would often be marked with an American flag painted on the side to indicate their stance of then-neutrality to prevent attacks. Thus, the duck does the same, content in the assurance that his neutrality will save him from the hunter. Despite the meaning of the gag largely being lost to time, benefits of solid art direction, a tangible crescendo in action and pacing, and general coherence of cinematography still prove to be beneficial.

No comments:

Post a Comment