Release Date: October 26th, 1940

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Chuck Jones

Story: Rich Hogan

Animation: Phil Monroe

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Elmer)

(You may view the cartoon here or on HBO Max!)

One of Chuck Jones’ most quotidian entries happens to be one of his most controversial. Thankfully, not to the myriad of reasons that other cartoons are controversial. It doesn’t boast any aspect that is morally objectionable, isn’t outstandingly egregious, isn’t shocking or disorienting. Just as innocuous as a cartoon entitled “Good Night Elmer” can be, it’s the innocuousness that lands it into such trouble in the first place.

Critics pan the short as one of the most boring Warner cartoons of all time. And, consequently, one of the worst. Such is a rather lofty claim that we will be seeking to investigate further. Is there a shred of truth to such claims? Is it all overblown outrage? The answer to both is: yes.

Worth mentioning is the title card design. Green and orange text pasted upon a magenta backdrop, the title is as unimposing as the cartoon itself. In any case, the same design and layout would be reprised first the title of Elmer’s Pet Rabbit—Jones’ next entry with the character. Whether a happy accident or purposeful in its intent, the synonymous titles establish some semblance of continuity between shorts, seeing as both primarily star Elmer. It doesn’t exactly mean anything, but is nevertheless intriguing to identify considering the independence of most title cards.

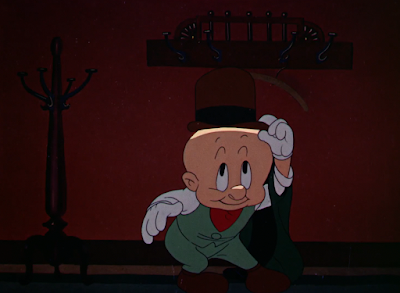

Keeping talks of design in mind, Elmer’s looks and appeal have taken a great jump since Elmer’s Candid Camera—Jones first outing with the character that wrought his official christening. Even in comparison to A Wild Hare, which saw a Fudd comparatively more recognizable to his modern counterparts, his design here is unequivocally him. The small, red nose in Hare is back to a moderately bulbous capacity, the refined proportions from the same cartoon are applied and modified to fit Jones’ wheelhouse of drawing, his outfit is dutifully resuscitated from his prototypal days, and so forth. While he was sympathetic in A Wild Hare thanks to the more squat proportions, this is the first instance of him being unequivocally, inarguably cute. Perfect to suit Jones’ purposes.

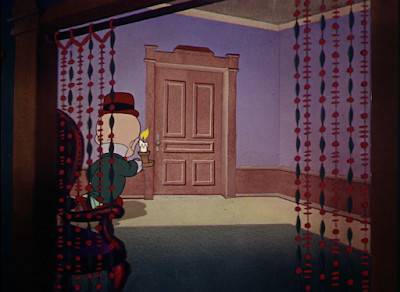

Even in the short’s newborn moments, atmosphere is a priority. A chime of the clock off-screen informs the viewer of the general setup—that is, it’s late. Paul Julian’s background paintings are carefully arranged to direct the tone through color; reds, browns, and oranges instill a cozy warmth, yet the blue background of the wall signifies the sense of nighttime where windows do not. Technical trickery is a big source of attraction for the cartoon; the glow of the kerosene lamp, appearing genuine in its light source, serves as the first hint towards such.

A camera pan over to the clock chiming in question is remarkably smooth. No jitters, no hiccups. Only a swift easing in and out of momentum that feels gentle yet tactile. An intricate up angle of the clock renders it more imposing, almost authoritarian in its command to send Elmer to bed. Regardless, a sense of coziness is much more dominant, thanks again to the richness in Julian’s painting, the sleepy reassurance of the clock chime, and Carl Stalling’s delicately muted arrangement of “When My Dreamboat Comes Home.”

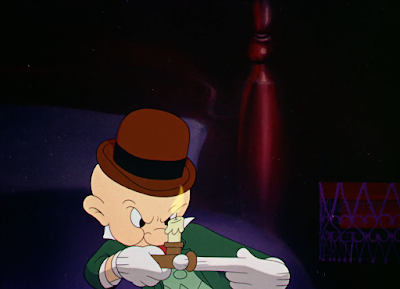

A yawn seeks to affirm all of the aforementioned hints building up to the crux of the cartoon. With bedtime firmly planted as an idea, Jones is thusly able to segue into more technical trickery. Elmer lighting a candle through the courtesy of the lamp is gentle, light, yet sophisticated and solid. Perspective and solidity of the candle itself render the actions believable; the same applies to the tapering, flickering animation of the candle flame. It’s flame shares the same benefits of the lamp through the double exposed glow—softness, believability, and visual intrigue.

Even a trip to the bedroom is comparatively extravagant. Briefly obstructing the audience from Elmer as he slips out of view from the camera bestows an interactivity to the environments; likewise, it introduces an organicism to the directing. Almost a sense of confidentiality, as though even we aren’t privy to the entirety of Elmer’s bedtime routine… despite only missing out on a few brief seconds of his walking. It’s a welcome touch of intimacy that fits snugly with the cozy tone of the entire opening.

Conscious color choices and variance in value maintain dimensionality, whether in a literal sense (such as the darkening hallways in the foreground) or symbolically, as is the case with the candle lighting up his dark bedroom. Framing of the scene encourages the cozy confidentiality; a bed and vanity clutter the foreground to make it seem as though we are gazing at Elmer incidentally, rather than dutifully following his activities. Likewise, poignant inclusion of the bed in the foreground again informs his motives—the bed seems more inviting by giving it more visual emphasis.

Undressing for the evening is where the first inklings of conflict manifest. Conflict in the story, and conflict from the viewers. That is, Elmer struggles to find a place to put his candle; he can’t take off the jacket without it getting in the way.

Complaints are admittedly justified, seeing as he struggles with the same issue with the opposite hand. It isn’t necessarily the content, but the execution; the scene lasts for more than a minute. The logical demand of the viewer is, of course, is to either put it on a nearby dresser or even the floor. And while that’s a good point, it does defeat the whole purpose of the scene. He doesn’t put it on the floor, because there would therefore be no conflict, and thus, there would be no cartoon. It is an indication of writing that could stand to be more well rounded and foundational, but is likewise a conscious move.

Switching hands in which the candle resides allows shadows and highlights to be flaunted from both sides of Elmer’s face; even the act of switching hands provides a glimpse of sculpted, believable perspective. Trails follow the candle flame as it moves, bridging the motions together and embracing a visual intrigue.

Though the main idea of the sequence stretches on for over a minute, Jones does briefly indulge the audience in an intermission. Elmer can only get away with switching the candle in his hands for so long before mental protests of “Just put it down somewhere” get too obtrusive—thus, the window provides his answer.

Just as it does another thorn in his side.

The “solution” itself may be frustrating, but the visuals it heralds almost justifies its usage. That is, when a gust of wind extinguished the flame, the entire room goes dark in a flash. No slow dimming, no reaction shot of Elmer before the flame is diminished. Such a sudden jolt is effectively jarring, and, thusly, effectively believable. Completely suspending the music in favor of cold, empty wind sound effects furthers the sense that something has been disrupted; an incredibly strong and effective juxtaposition against the warmth prior.

Delicate smoke trails on a dissipated match prove to be just as airy and careful as the effects on the flame. A difference in brushes helps greatly between distinguishing the two—the smoke from the match is formed through light streaks of dry brushing, whereas the flame has a much softer glow to give both unique textures.

Elmer now seeks to place the candle on his head, which works as a fine balancing act… until he runs into the same problem he had with the candle, only now with his hat.

Frustrating as the scenario may be (living dutifully up to its title as “frustration comedy”), it does segue into more sophisticated trickery with light. That’s what the entirety of the short hinges on—experimenting with light. Placing his cap over the candle does not only pose a fire risk, but hides Elmer’s light source entirely. Such is not to his liking.

The inverse is also, conveniently, not to his liking. Painfully banal as the actions may be, tracking the light sources as they are is playful and clever; having the hat cast such a vast cone of a shadow feels as though it’s been taken right out of a silent film. In a way, that isn’t too far off, given the lack of dialogue boasted by this cartoon.

Thankfully, Elmer does what he should have done a minute ago—put the candle down on a nightstand. Julian’s backgrounds continue to be a saving grace; airbrushing on the bed in the background not only renders it more inviting through its softness, but simulates an artificial depth of focus—objects in the background aren’t as clear as they are in the foreground. Despite such a wildly unbelievable premise and story (which feels redundant to even get mad at because of how banal and admittedly innocent it is), details such as staging, color, lighting, effects, and painting are very much rooted in the firm reassurance of believability.

That cannot be said for Elmer’s finger getting stuck in the candle holder. His struggle, rising from simmering frustration to a loose-limbed frenzy, does give way for more showiness on the trails of the candle and the tactility of Treg Brown’s sound effects, but little else. Again, it all boils down to one simple idea: Elmer’s finger gets stuck because there wouldn’t be a cartoon otherwise. Elmer doesn’t put the candle down immediately because there wouldn’t be a cartoon otherwise. There has to be some illusion of substance. Regardless, the finger getting caught requires a bit more suspension of disbelief considering he was able to pass the candle around so freely previously. An entire minute was dedicated to him situating the candle in various places on his body that are not in his hands.

Regardless, the dry brush trails as he whips the candle around give the reassurance of some energy. Brown’s whipping sound effects instill a permanence into the actions just as well as they support the flurry of action.

Such frenzied flailing likewise provides more availability for a sudden shift. With the introduction of Elmer’s failure to set the candle on the windowsill, the audience immediately registers that the sudden jolt of black indicates the candle has gone out yet again. In spite of its repeated usage, the shift is just as effective as the first instance, if not moreso—there’s no negative space of a window to inform any remaining light. Total darkness that is made more damning and suffocating through a longer, more staid pause in music and sound effects.

Relighting the candle once more, focus is delegated to a brief bit of character acting rather than entirely on effects. Lugubrious rubs of Elmer’s face reflect the thoughts of viewers succinctly.

With enough flailing, he finally does get the candle off of him—a cymbal crash marks a clever representation of bold finality. Fading to black as Elmer begins to take off his coat finally indicates a shifting of narrative priorities—we are slowly making our way to bed, which is a start.

Indeed, a fade in as we return to him dressed for the night confirms our suspicions. Keeping his gigantic bowler cap on in bed is an amusingly endearing and funny detail through its arbitrariness—there’s no way it poses any sort of discernible function. Yet, after all, what is a Fudd without some sort of hat?

After a few bloated moments of Elmer turning in for the night—moments admittedly justified, as they seek to capitalize on the cozy lethargy rather than pad out time through repeated banality—we finally say goodbye to the candle. Elmer blows it out, retreats off-screen, all’s well that ends well.

…or so would be the case, if three and a half minutes of runtime didn’t remain.

Consequently, a new dilemma is in order to coronate this second half of the cartoon. And what better way to achieve that than indicate the inverse of the first act? With the audience thoroughly and aggressively acquainted with Elmer’s plight to get some sort of light, we are introduced to the opposite dilemma: the candle refuses to go out.

Many of the “solutions” in the cartoon aren’t particularly funny—some boast more technical merit than others, and some are certainly more creative in their attempts, but seldom are they laugh out loud hilarious. A small exception stems from Elmer’s second attempt to extinguish the flame; his finger carries the torch by catching fire instead.

His flails are synonymous to those touted when his finger was stuck in the candle holder, but have the benefit of technical extravagance through a double exposed glow. Trails on the candle and dry brushing on his gloves or hat are tight and neat in remaining distinguished in their respective opacities; gripe as you see fit, but it is rather incredible that this cartoon could be made at all. Imagining the same attempt made two or three years prior and bogged down by blurring, flickering, or incorrectly exposed elements makes this one much more easy to appreciate. We thank Elmer for his patronage by burning his fingers to give us such meaningful comparisons.

Anthropomorphizing the flame gives it a little more novelty and justification in its resilience. Appealing to Jones’ earliest instincts as a filmmaker, the anthropomorphism is a cute callback, welcome embrace of surrealism in a cartoon that needs it desperately, and an acknowledgement that this struggle is totally ridiculous. Elmer’s frustration, likewise, feels more empathetic and sincere.

Slamming his palms onto the candle ensures no risk of fingers getting caught on the flame. Though a slight detail, having the candle buckle beneath the weight of his hands and create a permanent mold does again contribute to the short’s cause of making the environments feel lived in and interactive.

Additionally, it compliments the close-up of the flame reigniting nicely. Makes the sting of its existence hurt even more; the candle has been beaten and battered, but not its spirit.

A charade thusly ensues between Elmer and his candle playing a game of peek-a-boo. Elmer glares at candle. Candle goes out. Elmer goes back to sleep. Candle relights. Jones does what he can to keep the momentum varied, though is a dying cause in such innate monotony. Out of the four times this occurrence unfolds, two of them are back and forth shots, the next informs the actions of the candle purely through the lighting dimming and rising while focusing on Elmer, and Elmer getting out of bed places the final nail in the tangential coffin. Pacing remains bloated, actions remain monotonous, but there is an attempt to keep it varied.

A reprise of anthropomorphic qualities seeks to achieve the same. Kitschy and cutesy as it may be seen as to make the candle react like a human, Jones succeeds quite well at making its motives clear. For a flickering element that displays no discernible features, the little flame is able to emote quite a lot. Strong lines of action and careful animation choices—staggering forward to indicate hesitation, a literal slow burn to indicate sneakiness, a fast retreat to indicate haste at getting caught—do wonders at informing the action. This short can take all the clarity it can get.

A coil on the flame as it makes a hasty retreat attempts to embrace variation how it can. Here, the effect is sophisticated and playful. Such extends to the flame itself and the trails of smoke that follow—some thick, some thin.

In any case, the back and forth does grow tiresome. That applies to the entirety of the cartoon, but is especially poignant in this particular close-up of the flame going on and off, Elmer retreating and entering. Staging it all in the same register can be effective in establishing a wry, ironic tone through its simplicity, but quickly grows boring without any sort of directorial variation. Each time the flame is extinguished, the viewer assumes it to be the last. Then, right on cue, the hopes of the audience are dashed each time.

Slamming a book on top of the candle introduces some semblance of finality. If only for this scene, anyway; with a little over two minutes remaining, the audience knows this is surely not the end of the battle. The book is just another vessel for trouble.

With the slow ride of smoke emanating from the middle, that’s exactly what a close-up of the book seeks to prove. Elmer, not often regarded for his impenetrable logic, becomes the victim of his own resolution as a hole is burnt right through the book. More light is thusly flooded into the room. Good news for those hungering for more effects and storytelling through lighting; bad news for anyone else.

Whether conscious or otherwise, many of the incidents or execution of said incidents seem to take inspiration from Porky’s Badtime Story. Both cartoons have the same basic presence: menial annoyances that snowball into a bigger force preventing the main character(s) from getting sleep. Seeing as Jones was essentially a de-facto co-director on Bob Clampett’s earliest films, providing character layouts and informing the look of the cartoon, the comparison between the two is justified through his intimate role on the short.

That, and the mirrors in execution between gags. Elmer popping his eyes open just for the flame to conveniently go out parallels Porky’s struggle with a sentient curtain letting moonlight in and out; predictably, the execution in Badtime is much more fast, varied, and embracing in its surrealism, but the comparisons are there. A prevalence of “When My Dreamboat Comes Home” aids in establishing similarities.

No matter how boneheaded the decision to cover a candle with a book may be, it does—thankfully—encourage one particularly creative payoff. That is, Elmer catches a glimpse of the lit flame in the mirror next to him. It’s as though the mirror is telling on the rogue flame attempting to tease its host, just as it seems to betray Elmer, who would be content with the bliss of ignorance. A quick, dry camera pan between the mirror and Elmer constructs a dry, ironic commentary that is despairingly needed.

Comparisons to Badtime grow more concentrated through Elmer’s solution. Or, more accurately, the eventual breach of said solution. Shielding the light of the flame with three books only prompts the flame to creep taller, elaborate lighting effects informing its movement on a closeup of Elmer. Said maneuver again parallels Porky’s struggle with the curtain, but likewise channels the surrealism of the moon changing positions over the house to blind him regardless—it’s that sort of contradictory anthropomorphism that unites these cartoons.

A silhouette shot of Elmer in the foreground seeks to introduce a new novelty to the formula how it can through visual flourishes. The maneuver is appreciated, but loses its importance as the cartoon stretches further. By the time Elmer interrogates the flame for the umpteenth time, prompting it to go flaccid in defeated embarrassment, the viewer is completely apathetic to the effect. Drawings and effects are very nice, and the motives behind the candle try to be interesting, but the monotony of the premise is too strong of a desensitizer.

Likewise with Elmer breaking the candle into two. A clever solution in differing circumstances, but the expectation of the flame still making a return is too strong and overwhelming to embrace the surprise aspect intended. Effects and animation of the flames coming to life (as well as the sculpted shadows on Elmer) prove yet again to be a stronger point of appeal.

No comments:

Post a Comment