Release Date: February 15th, 1941

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Tex Avery

Story: Rich Hogan

Animation: Bob McKimson

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Quail), Tex Avery (Willoughby)

(You may view the cartoon here or on HBO Max!)The premise of The Crackpot Quail is simple: a stupid hunting dog pursues a quail by means of sustenance, but finds himself as the brunt of the wise-cracking quail’s heckling instead. It’s been Avery’s pet formula, and would continue to be throughout his career. Stupid meets snappy.

So, to hear that the cartoon was rejected by the censors and was one of Avery’s bawdiest moves to date comes as a bit of a surprise.

All roads lead to the Hays Code, as they so often did in post-1934 theatrical cartoons. It wasn’t the premise of the cartoon that was deemed problematic. Rather, the sound emitted by the quail to indicate its presence: a raspberry. This again seems rather pedestrian by today’s standards, and there certainly is a shrapnel of truth lodged into such a deduction. Yet, it was Avery’s handling of the raspberry that proved troublesome; in true Avery fashion, the raspberry is repeatedly emitted over and over and over and over again upon the quail’s introduction. Likewise, Willoughby (freshly streamlined since his debut in Of Fox and Hounds) hawks a particularly loud, wet, extravagant raspberry that doesn’t seem to serve any other purpose but tauntingly wave the red cape in front of the raging eyes of the Hays Office.

It was only recently that the original soundtrack for the cartoon was uncovered. You can hear a sample of it for yourself here.

Even if any auditory indication of a raspberry had to be dubbed over by whistles instead, effectively nulling Avery’s mission, such a risk serves as a testament to his priorities of the time. There is no way that the cartoon wouldn’t have been flagged—especially when it makes a point to be as flagrant as humanly possible. Purposefully inciting, it demonstrates his growing boldness and perhaps even a restlessness with his material.

By now, he’s come down from his travelogue high; only a few at the bottom of the barrel remain. Now, he’s seeking to innovate further, shock further, and will go to lengths such as making cartoons that would immediately get him in hot water to do so. This “acting out”, if one could call it that, foreshadows the path he would take with the majority of his filmography that lies ahead. Such is, likewise, a testament to his legacy as the king of cartoons—he would sacrifice a run-in with the censors all in the name of getting a laugh. The only thing that could obstruct him from achieving his vision was himself. That, coincidentally, proved to be a somewhat frequent hurdle.

Even with a significant hook of the cartoon excised, it still proves to be coherent, competent, and—most importantly—amusing in its surviving form. Willoughby his since shed some of his Lon Chaney Jr.-isms; Avery still maintains the voice and general attitude, but he’s outfitted to mold to the demands of the cartoon (that is, a chase) rather than serve purely as a character study. Likewise, the quail is yet another stock Avery heckler, but to a much greater degree of success than what was touted with the mouse in The Haunted Mouse.

Johnny Johnsen’s range as a painter often proves beneficial for Avery’s comedic narrative. He could paint animals and humans with the same steadiness and security as he could backgrounds and environments, which proved to be a very valuable skill in cementing realism. It’s especially valuable for juxtaposition, as is the case here.

The noble pointer dog, picturesque with his long, flowing coat and rigid stance, proves to be everything that Willoughby is not—such a notion is teased as the camera pans out to reveal one Willoughby in question, contentedly wagging his tail at the advertisement for dog food. “BARKO” and “DOG” on the billboard create a cohesive visual frame around him by sandwiching his head in the middle; very clear in both composition and intent.

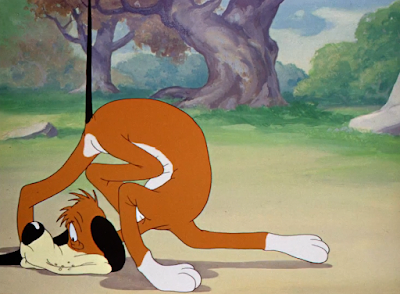

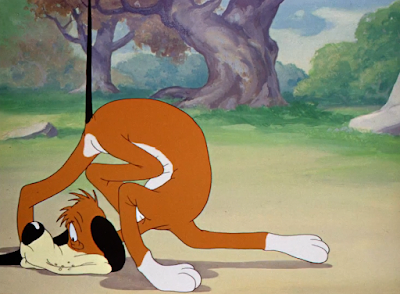

Indeed, as mentioned in the introduction, Willoughby has been given a makeover. He’s much more lanky and gaunt, which arguably offers more clarity for exaggeration and humor through distortion. Thanks to such thinness, his line of action is more traceable, thusly rendering poses readable and comparatively dynamic. Likewise, his muzzle is much more pronounced compared to his cranium; it seems more like a “liability” with its giant, big floppy jowls dominating so much room on his face. A physical mass that doesn’t seem to be comfortably supported by his tiny, spindly little neck.

His old design is independently charming through it’s own unique benefits: the sense of sheer elasticity through his weight, the softness making him seem more cuddly and unimposing, and just the benefit of not looking like every other cartoon dog—a vice that the “new” Willoughby slips into, but even that is debatable. It was through Avery and his cohorts that these cartoon dog design stereotypes were cemented; is it slipping into a design stereotype if he helped to pioneer it?

Nevertheless, these refinements seek to offer a broader range of versatility through acting. And acting, Willoughby is full of; a swelled chest, a deep sigh, dutiful, and aimless nods of the head that seem impulsive rather than cohesive all convey his lustful envy with ease. In spite of the caricature and absurdity innate to his actions and thoughts, there stems a sincerity in such commitment. One gets the idea that his sighs and guffaws of “Ohhh boy, huh huh... tha… tha’s the life,” are nothing but honest… even if he looks, acts, and sounds funny while saying it. There’s a sincerity to his spectacle.

“I’m gonna be a pointer an’ catch me a quail!” exposes to the audience that he is indeed musing about being a hunting dog—not a dog food advertisement, though it seems he’d get similar ecstasy from that, too.

A sudden change in demeanor accentuates Willoughby’s flightiness—an “An’ I will, too!” is marked with his full attention turned towards the camera, a wink indicating his determination and drive. It’s almost as though he knows the audience is politely doubting his incompetence as a potential hunting dog. Such a declaration is the first of its kind in the Warner cartoons—it would soon evolve into a pet catchphrase of many a short, including many of Avery’s at MGM.

Such determination is caricatured through the extravagance in which he prepares a running start. Avery and Treg Brown poke fun at the sudden boldness through purposefully deceptive sound effects; the build-up, while motivated and strong in its individual poses, is much more calculated and slow than the winding turbine sound effects lead on. Raging engine sounds accompany the mere action of Willoughby standing up—such is to pronounce his drive and give it a physical manifestation, but also seems to poke fun at the suddenness of his gumption.

Especially when such buildup quickly results in Willoughby ramming into a tree. It’s such a sudden development that the camera momentarily loses sight of its target; there’s a considerable amount of time allotted as the camera keeps moving forward, slows to a halt, and very cautiously backs up to reveal a vacant, confused Willoughby nursing his wound.

Growing integration of the camera into the filmmaking by gifting it with its own voice has been one of the greatest advancements of these shorts within the past few years. A new avenue for humor and even sympathy is immediately opened—the speed at which a camera moves or even stops can communicate a wide range of emotions. Irony, deceit, sympathy, confusion, exuberance. It provides a very tangible means of giving these cartoons a meta edge that isn’t solely reliant on the characters speaking to the screen. Likewise, it further integrates the audience into the picture and values their presence through such decidedly human maneuvers. A reminder that we’re all spectators; including the very hands that made this cartoon.

.gif)

Willoughby’s obsession with identifying trees served as a carryover from Of Fox and Hounds; already, Avery has found a way to streamline the routine—his spiel in Hounds (“‘Cause I know every tree in this forest! Every single tree! …There’s one now!”) has just been shortened to one word and a guffaw with the same takeaway:

“Huh huh. Tree.”

The action of rubbing his head lingers for a few seconds too many—perhaps to give added innocence and empathy to his blunder—but is nevertheless replaced with an inquisitive, startled action. Such serves as a response to the quick, staccato whistling from off-screen.

Character acting is nice and subtle on Willoughby; it’s clear he’s using all of his brain power to determine the source of the noise. First, he does a take. Then, a lifting of the ear. An accusatory squint at the audience builds empathy and immersion, as though he’s asking “Are you hearing this?” or even “Are you this?” Likewise, looking up at the tree in front of him serves as a nice acknowledgement of his surroundings and a bit of founded logic. Birds often whistle. Birds often reside in trees. There’s a tree… and so on and so forth.

Ever conscientious and purposeful about planning, the hiding spot of the whistle-bearer isn’t an entirely new location to the viewers. A series of camera moves reveals the quail to be hiding behind a rock—the same location where the camera came to a pause to look for Willoughby after he crashed into the tree. It’s a very subtle maneuver, but allows the flow of ideas to read coherently and keep the audience grounded in the action. Digesting all of the expositional information in little, tiny chunks.

Expositional information such as “What the heck is the source of the whistling”; it‘s the sound of the quail contemptuously blowing the feather out of its face to little avail. For all of the trouble it took to get the cartoon out the door, the whistling fit comfortably into the action. Save for one scene of Willoughby mimicking the sound, one never would have known that a previous soundtrack existed. Avery and company did a great job making do.

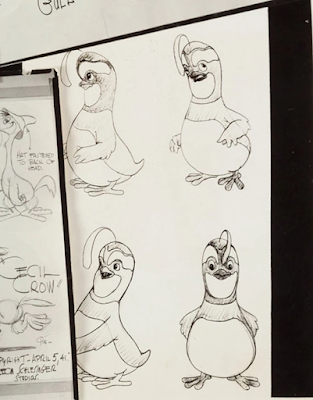

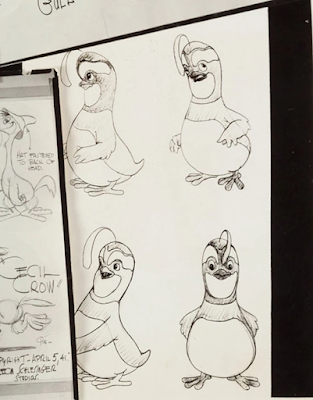

What follows is a somewhat needlessly lengthy sequence of the quail attempting to tame its plumage. 30 seconds on the same close-up runs a bit long, but serves as a proper way to endear the quail to the audience. Willoughby by nature proves to be more endearing, so the endeavor seems a bit aimless, but there is a palpable charm in the quail’s facial expressions, emotions, intents, and innovations.

Likewise, it helps that the animation and art direction is incredibly solid, constructed, and full of appeal. These character highlights, while a bit bloated, come as a major refresher. Given the slew of travelogues that preceded this and other recent Avery shorts, it makes sense that he would want to indulge in these footnotes of character and personality. Spot gag cartoons don’t offer much time for a character to endear itself to the audience nor exude a substantial amount of personality. It’s a welcome change of pace and an opportune time for the animators to flaunt the rapid development of their work. Such grace and liveliness in the movements and solidity in construction would have been unthinkable even two years prior.

A cut back to Willoughby seems somewhat sudden, but that very well could be a symptom of the quail’s feather antics taking up so much screen time. Evolution in art direction and animation extends even to a difference of mere months—the dutiful sniffing cycle first touted in Hounds has likewise received a fresh coat of paint and exaggeration to match his streamlined design.

In spite of losing so much weight, he seems to lumber more—he practically snaps his neck by sniffing under his torso, moving his head back and forth like a canine vacuum cleaner with a one track mind. Behind such amusing movements lies a steely sense of purpose. Willoughby may not be very bright, but he is exceedingly loyal to whatever is occupying his fleeting attention span in the moment. The walk cycle is hilariously animated and speaks a great deal to his character. It looks, moves, and acts funny; all that one could ask for.

Likewise, such a walk cycle proves to be rife with comedic potential: in this case, irony. In spite of Willoughby’s laborious—if not obsessive—sniffing, the quail himself is the one who has to get his attention. A nasally “Whaddaya say, doc?” following a whistle immediately informs the audience that this little bird has a few tricks up his sleeve. He, too, is a philosopher of the Bugs Bunny school of trade—the colloquial language, the innate conceit as he observes in contented nonchalance. He already has the upper hand by not doing anything at all.

“Pardon me, shorty, but uh, huh… uh, did ya hear a funny noise around here that went lah-ike thee-us?”

A profuse spray of spit and violent convulsions make up Willoughby’s demonstration, serving as the most obvious indicator of a disconnect between the new soundtrack and what’s on screen. Thankfully, the protruding tongue still passes as a shorthand caricature of a whistle—nobody would have guessed differently, even today. Regardless, the animation in itself is fascinating through sheer novelty alone. Such violence and volume in the performance read as nothing but a giant middle finger to the censors—there was no “We didn’t know it would get flagged!” involved. No faux innocence of any kind. Such proud deliberation is what made Avery so unique—an unabashed sense of purpose. Even if that purpose would knowingly land him in trouble.

“Nope I didn’t—“ A whistle immediately cuts into his words,” “doc.”

It isn’t so much the whistle/raspberry that’s funny, as is the implication behind it. That is, the quail knows he can carry on a conversation absolutely infested with the offending whistle, and Willoughby wouldn’t question it once. Again, very Bugs-like in his unwavering confidence.

It helps that Blanc’s vocal deliveries seem exceedingly genuine in their hackiness. Not hackiness in the sense that he’s a hack, but how his phrases are constantly getting hacked into pieces with the whistles. The quail is very aware that he’s doing it, but the act of whistling and talking in themselves seem like a natural compulsion. A mild interruption that he pays no attention to. Purely instinctual. Blanc perfectly captures that sense of compulsory behavior through stilted, breathless, almost hiccup-y deliveries.

“Been around here—fwip!—fer twenty years—fwip!—never heard a noise—fwip!—like that—fwip—before!—fwip!”

“Well, uh, huh, uh… uh-thanks anyway.” Avery allows Willoughby to endear himself to the audience further, as well as garner more sympathy for him. His next observation of “Uh, I thought it mighta been a quail!” indicates that he would have been right on the money if the quail hadn’t been there to mess with him—maybe.

Interestingly, the quail’s demonstration of what one truly sounds still manages to survive the perils of the lost soundtrack. That is, the original soundtrack seems to have the quail actually whistling as he does here—said whistle amounts to a wolf whistle gag, which accompanies the quail’s gesturing of a curvaceous woman. In spite of the raspberries being dubbed with whistles, potentially muddling the independence of these intended (wolf) whistles, it almost works better that way; the new whistles from the quail still have enough differentiation in tone and emphasis to gain independence and effectively trick Willoughby. A gag that could have been lost is cleverly saved through some forward thinking on how to approach the dubbed whistles that was very much intentional.

Willoughby’s interrogation of the quail is beautifully drawn. His features, which are plentiful—wrinkles, folds, flaps—are rooted in solidity and construction. Muzzle, paws, nose, ears, even eyelids, all are animated with such tactility that the audience feels as though they could reach into the screen and squeeze them. That applies doubly to the eventual close-up of the two characters.

Indeed, Willoughby gets wise to the quail’s presence. Again, his growth since

Hounds has been noted, as now he’s cognizant enough to trust his own gut. In the former cartoon, he barely shows any indication of recognizing George as the fox. When he does, it’s rather deep into the cartoon, and is quickly convinced otherwise. Here, his deductions come much quicker. Some of that happens to be out of narrative necessity—it is a chase cartoon, after all, and the entire cartoon can’t exactly hinge on Willoughby wondering what a quail is or is not.

“He’s a card, ain’t he?” Quail’s breaking of the fourth wall feels natural and innate. At this point in Warner’s filmography, meta humor is just another fixture of the cartoons. Not that the novelty is lost, but it feels at home with the cartoons rather than the occasional groundbreaking oddity. This “normalization”, for lack of a much better word, allows the writers and directors to make these breaks feel more organic and charming, driven through genuine character rather than a spectacle that halts the flow of the short. Indeed, the quail’s quip (albeit snarky) feels believable in its affability. The same can be said for Willoughby’s glances and statements towards the audience.

Comparisons between Bugs and the quail are at their zenith with the following outburst of “

YOU’RE RIGHT!!!!!!!” A direct reprise of the same bit from

A Wild Hare, cruelty and general abrasiveness is given a tighter embrace here. His yell is ear splitting enough, but the shrill shriek of a whistle that follows deliberately seeks to deafen and disarm. Such an intimate camera angle also allows for the audience to read Willoughby’s facial expressions better than what was presented with Elmer in the former; thus, it’s easier to sympathize with him, which makes the assault from the quail even more violent.

Grabbing the dog’s nose and slamming it back into his muzzle allows the animators to flex their muscles a bit more. The action is exaggerated and rooted in squash and stretch principles, but maintains its volume all throughout. Very sophisticated animation for such a proudly juvenile move.

Twinkle toes exit is, likewise, an extension from Bugs’ own in

A Wild Hare. Now, Willoughby means business. Whirring engine sound effects to accompany his running wind-up are much less ironic this time around, carrying a legitimacy that matches the ferocity in his movements and face especially. Likewise, he spends less time preparing than he did before—now, time is precious, and he needs as much of it as possible to pursue his prey.

While the ferocity in his wind-up differs, the outcome is the exact same. Again, the camera outruns its target; this time, however, the reaction time is much shorter. It comes to a stop much quicker than it did before, as though it had been conditioned to expect this sort of outcome; integrating the camera into the film and making it a supporting character in itself is, again, a testament to Avery’s genius.

Understanding that the gag is monotonous in itself, he tries to differentiate and be as flexible with the gag as much as he can while still retaining its repetition. Rather than rubbing his head cluelessly, Willoughby has flopped forward this time and slowly lifts himself off the ground. This way, there’s a bit of organicism maintained between each “tree take”; it reads as a genuine err on Willoughby’s part, rather than the director seeing how much he can grind the audience’s nerves by repeating the same joke (though that is very much a variable as well.)

As though to compensate for the intended staleness of the gag, the sequence that follows is fresh in its innovation and novelty. Rather than being just a chase between

cat and mouse dog and quail, it’s, more accurately, a stylization of one—a summation, a caricature.

Ever mechanically, both predator and prey hide behind the various trees painted for our viewing pleasure by Johnny Johnsen. Movements are stilted, rigid, dronelike in that the only real movement stems from the drybrushed stylization of their legs. The bodies of both bird and canine seem to just glide across the screen. Both also receive adjoining musical cues that further accentuate the mischief of the caricature—the quail gets a flighty flute accompaniment, whereas the dog’s brass glissando is more brazen and razzing.

Movements get faster and faster, more repetitive and more absurd; in moments, the characters practically seem to be chasing duplicates of themselves. There’s a great restraint on Carl Stalling’s part (and Avery’s direction) by limiting any and all music to that of the accompanying movements. The audience is thereby forced to focus on the rigidity and hilarity of the sheer caricature—it’s supposed to look absurd. This sort of subversion and betrayal to a “real” chase would be something Avery would embrace, refine and perfect in coming years.

Further asininity of the chase is exemplified through the entry into a log—another holdover from

Hounds. Here, the log is just a means to a gag rather than providing a conflict, as in the former. A very subtle gag, one might add, as there are no sudden stops or breaks in momentum. Willoughby is the last to enter the log…

…but first to come out. Avery doesn’t give the audience adequate time to chew on the gag or how it happened; justification would kill it. That it happened at all is the main priority.

Willoughby’s diet plan does somewhat lose the impact of his ridiculous run cycle from

Hounds being reprised here, but that’s much more a case of the original being so absurd and hilarious rather than this run being “bad”. It’s still very much amusing to watch, and his newfound sleekness allows the poses to be more defined, visible, and dynamic. Still, there is a lovable quality to his lumbering, heavy galumphing that proves hard to substitute. Nevertheless, he carries himself with much more purpose and conviction… though his awareness remains about the same.

Said run cycle does ultimately prove to be a crutch, in that it fills up more time than necessary; a close-up demonstrates the quail gaily surpassing his not-quite pursuer, bidding a chipper “Good morning, neighbor!” and a whistle as he passes. That in itself is timed just fine, flute glissando maintained to match the flurry of his leg movements. However, there comes much too long a pause before and after his appearance—about 11 seconds of empty airspace combined. Perky musical accompaniment, hypnotic momentum from the camera and animation, and tight draftsmanship as a whole render this as a rather forgivable cheat. Regardless, it’s a blank space of idleness that Avery wouldn’t have been caught dead with in just another year or two.

Realization nevertheless strikes, no matter how long that may be achieved. Willoughby’s “curious dog” acting is great throughout the whole short—the perked ears, the inquisitive cock of the head, the wide, alert eyes, the erect tail, the bow legged stance. All indicate an innocent curiosity that indicate the gears are turning, but not in full confidence; there’s a certain childlike curiosity in his deductions, as though he’s searching for the nod of the viewer’s head to justify his findings.

“That was the quail!” is delivered with synonymous breathlessness heard in

Hounds, particularly with his “Ya know, that was the fox!” Here, a certain matter-of-fact-ness takes precedence over the confidentiality of the former.

Rinse and repeat with some more tree collisions. At this point, the gag has worn out a bit, but proves difficult—like many of Avery’s self indulgences—to hold a grudge against. One can imagine Avery’s glee at the prospect of this joke and purposefully running it into the ground. He does do what he can to keep it fresh, as mentioned before—differentiation in camera speeds and positions, as well as Willoughby’s reactions, do a lot to keep the gag tolerable and even enjoyable.

Such as here. Now, instead of outrunning and making a retreat, the camera remains absolutely still. A cacophony of sound off-screen illustrates the collision, and the camera merely slides over to reveal the inevitable. Routine has firmly been established and embraced.

Even Willoughby entertains such mundanities. Now, he doesn’t even bother to rub his head or blink at the audience. Just another matter of fact “‘nother tree,” followed with a somewhat defeated stare at the perpetrator. There’s a poignant leisure to his pose, with the slumped shoulders, hand resting on his stomach, half-lidded eyes. An apathy indicating routine, and perhaps even an unspoken “Shoulda known.” That in itself manages to evoke the same amount of sympathy as is gathered from his head rubs or illuminated blinks.

Even the filmmaking adopts an indifference of sorts—rather than having Willoughby climb back to his feet and keep trucking on, the camera merely fades to black. Such accentuates the aforementioned notes of resignation; it’s just a fixture of the cartoon now.

A fade also allows for a more definitive transition to Willoughby’s next hunting endeavors. His ridiculous sniffing cycle is now slightly built upon, bearing the new addition of musically timed butt thrusts every handful of beats. It both justifies and contributes to the sardonicism dripping from the ongoing score of “

Ya Gotta Quit Kickin’ My Dog Around”.

Quail tracks on the ground serve a greater purpose than a mere visual guide. Rather, they kickstart a visual gag of Willoughby’s nose and muzzle distorting to match the equally incomprehensible pattern of the tracks widening and tapering again. While nothing particularly special, the execution is plenty steady and fun—Willoughby’s unwavering call to duty is what makes it so amusing. No self aware japes regarding the distortion of his muzzle or confusion following the bird’s trail.

Confusion that would be justified, as its path deliberately gets more absurd—the quail trail finds Willoughby diving snout-first into a pond. Any signs of awareness are not close by. His unquestioning loyalty is both inspiring and confounding, there to assert the nature of his one track mind. He is nothing but determined, for better or worse.

In fact, realization strikes only at the last possible moment. It takes a school of fish swimming by to jar his attention loose, which is again coupled with more beautifully animated character acting. At first, his awareness is nonchalant, eyes merely following the fish swimming above its forehead. It’s the pause that follows with a sudden jolt of movement that indicates his true registry. Thus, the wide eyes, agape mouth, perked ears, and all other indications of befuddled curiosity follow. Exaggerated enough to be funny and read clearly, but still rooted in enough sincerity to be believable.

The quail is—of course—among the school of fish, both as a means of disguise and to screw with Willoughby some more. Mainly the latter. Here, the antithesis of his appearance is proudly enunciated through the difference in design and draftsmanship between bird and fish. All of the fish are approached with a much more literal depiction, very realistic and solid in their design sense. Softer, arguably cuter stylization of the quail allows him to stand out even further. The same could be said for the sudden flute glissando that hops into the tinkling accompaniment of “

The Umbrella Man”, said flute layered only after the quail is visible.

Avery’s signature “head shake take” of the late ‘30s and early ‘40s has slowly received refinements as it gets used more and more. Willoughby’s rendition of the same take is particularly striking—it feels like a genuine emotional impulse rooted in his intentions and feelings rather than a decoration that Avery and the animators thought looked funny. There’s a motivation and confidence behind the motion that hasn’t always been present in other renditions.

Given the exaggeration of the animation, there does prove to be a very slight dissonance between scenes and animators. Not nearly noticeable enough for the audience to register nor care about, but the animation of Willoughby lifting his head out of the water is much more tame, controlled, and leisurely than the alarmed motions leading up to the switch.

Nevertheless, such nitpicking doesn’t matter—the quail is the one who is meant to command the audience’s attention. Here, his topknot is utilized for further comedic potential; in this case, assuming the stylized shape of a submarine’s telescope. Or, upon realization of Willoughby’s presence, a question mark. Innovative acting that serves as a throwback to some of the earliest animated cartoons; the question mark imagery is particularly reminiscent of the acting and innovation in the Felix the Cat cartoons.

A close-up of said top knot being used as a windshield wiper is much more native to Avery’s house style. Perhaps some of that stems from the resemblance to the quail’s 30 second introduction at the short’s beginning; the staging and timing are very reminiscent. The staging does prove to be somewhat awkward in its intent; the manner in which the quail faces the camera head on almost seems to suggest that there will be some sort of regard for the audience, perhaps with a knowing glance or cocky aside. None of that happens, and probably for the better—regardless, the staging is a bit intimate and seems to suggest a topper of some kind that never follows through.

More chasing thereby ensues. Given the comparative cuddliness seen in Hounds (and even the informal, amiable relationship established with the viewer in this short), Willoughby’s intensity with the rapid speeds and bared teeth is genuinely disarming. Enough to justify the “Uh oh,” and desire to flee from the quail.

Cornering the quail allows for a vulnerability that keeps the cartoon interesting. There’s only so much fun to be had when knowing that, no matter what, the quail is always going to end up on top, and Willoughby must be chained to aimless pursuits. As such, this little vignette is imperative in keeping the audience hooked on the chase dynamic. Variation induces interest, and Willoughby being within an arm’s reach of killing the quail is certainly of intrigue.

Of course, nearly two minutes of runtime remain. For Willoughby to get his comeuppance now would be a grave mistake—what would remain of the cartoon? So, thanks to some quick thinking from the quail (and availability of a nearby stick), he plays on the dog’s impulses as means of escape.

“Here, Rover! Here, Rover! A stick! Here! Go get it, go get it! Quick! Bring it back! Go get it! Go get the stick, quick! Bring it back!”

Willoughby’s excited dog acting continues to entertain and endear. Now, he fetches the stick with the same ferocity as he had once pursued the quail. Stalling’s music score is imposing, threatening, thundering; an apt caricature of his drive to retrieve, but an amazing incongruity to the joyful expression on his face and asininity of his running.

Moreover, his retrieval of the stick marks a wonderfully pungent change in demeanor. Light on his feet, spry, a picturesque example of man’s best friend, he trots with prideful ecstasy. Despite being the same score of “Ya Gotta Quick Kickin’ My Dog Around,” it’s transformed into an entirely different song through its equally gay, jolly orchestrations—tinkling, effeminate, joyful. A wonderfully powerful contrast established quickly and coherently, all in a matter of seconds.

That too is applicable for his eventual realization that he’s been duped. Though a more gradual change (spurred through a series of befuddled head shakes between the camera and off-screen), the gravity remains the same. Suddenly, the stick has lost all meaning. He knows he’s been taken advantage of. Or, at the very least, he recognizes that something isn’t right.

The following close-up shot proves to be one of the most memorable beats of the cartoon, particularly through what it represents: the anger that shadows his face in real time proves to be rather alarming. It’s rooted in sympathy—how could he not feel so vengeful at this point?—but given his persistent docility in Hounds and even in this cartoon to a certain extent, it comes as a very surprising change. He had already been annoyed, determined, ready to kill beforehand. What does that make him now?

One gets the sense that his snapping of the twig with his teeth has more symbolism behind it than he may even realize. Sound effects of the twig buckling, unthreading and snapping between his jaws are made a priority to accent the intensity. Ditto with the foreboding din of a drumroll in the background—no razzing musical accompaniment, no angry sting. The drawings, the music, the sound effects, the staging, and the intent all pull their equal weight in concocting a beautifully threatening character beat.

Understanding the gravity of the close-up, Avery seeks to alleviate some of the heat through means of more trees. It’s been a hot minute since the last collision—enough time for the audience to let their guard down, which is why this impact happens when it does. Not because Willoughby slamming into a tree is funny. But, rather, because it’s an inconvenience, and the inconvenience is what’s funny. Now, the camera is trained to immediately follow Willoughby right to the tree. Everyone is in on the act.

Even Willoughby, who wastes no time identifying nature’s best roadblock. He knows, we know, and he knows we know.

…Possibly. It’s a very well timed bit, and the unflappable, almost courteous explanation of “‘nother tree,” proves to be a great juxtaposition against the intensity broiling just seconds prior.

Nevertheless, that same intensity returns through yet another absurd run cycle, this time peppered with heavy “ROUWF! ROUWF!”s. Johnsen’s gorgeously rendered backgrounds are now just an airbrushed backdrop to convey motion blur and speed. Willoughby is going so fast that the details of the forest don’t have time to register to the viewer. At least, such is the intent; the speed of the run cycle and camera remain the same.

“That means I’m gettin’ plenty sore!” explains Willoughby to the audience. Where would we be without his constant explanations of what a tree is or how he’s feeling? Lost, aimless, confused. We are forever at the mercy of Willoughby the tour guide, and for that, we are grateful.

With that, we return to the core of Avery’s directorial being. A grasp on a concept that immediately set himself apart from his peers with his very first cartoon all the way back in 1935, and something that would only continue to evolve in its caricature and handling. An aspect that comes up frequently in discussions of his work: speed.

Gold Diggers of ‘49 flaunted Mach levels of speed that animation as a whole had hardly been privy to prior. Now, with six years of directing under his belt, Avery has learned how to manipulate it into something more. Speed isn’t the only takeaway of Willoughby’s frenzied running. Now, Avery is able to make room for emotional intensity. Indeed, the combination of dry brush, accelerating engine sound effects, the determination in Willoughby’s face, animating the movement on ones, the motion itself climaxing over time, and the rapid fire orchestrations of “

William Tell Overture” speeding up faster and faster to match the action all make for a very powerful caricature of speed.

Eventually, all laws of physics are defied as Willoughby transforms into a dog-rocket. That in itself is particularly reminiscent of the speed bursts in

Gold Diggers, though much more driven in this case.

Unfortunately for him, the quail is smart enough to get out of the way rather than entertain the chase any further. More vulnerability is instilled with the bird as he struggles to pump his breaks and make a sudden left turn; as the music continues to climax in speed, tune, and overall representation of Willoughby’s presence, the audience wonders if the quail will even have enough time to move out of the way. This very well could be it.

A grin slithers onto the quail’s face as he realizes he’s in the clear, but that is quickly replaced through a look of horror as brake effects begin to trump the music. Obnoxious as he may be, the quail feels some sympathy on behalf of Willoughby. How could you not? His look of petrification—furthered through the inevitable onslaught of crashing effects off screen—indicate that he isn’t out to torture the guy or to get him hurt. His heckling is all in good fun. Obnoxious fun, but fun nonetheless. So, if even the quail is startled at the impact off screen, then that indicates a certain severity that piques both the audience’s curiosity and sympathy.

Enter the long pan to end all long pans. Nothing but 30 seconds of ear splitting crashes, snaps, bangs, collisions, smashes, thunders, all echoing against the continual squeal of metaphorical breaks. It is the genuine, textbook definition of a cacophony, but even that isn’t what makes the pan so great. That’s just a mere fixture on top of what is communicated through Johnsen’s lush background paintings: tire marks in the dirt to further the metaphor, a broken stone wall, snapped trees, even a log cabin now in complete disarray, various furniture items strewn outside to indicate the length and ferocity of Willoughby’s travels. It’s enough to make the audience immediately feel bad for him, eliciting an “ouch,” and a wince, but the visuals (particularly the addition of a downed outhouse, again there to thumb its nose at the censors) are often so extravagant and absurd that a laugh can still be elicited safely.

It’s a beauty of a camera pan. One could argue that it goes on way longer than necessary—just as you think it stops, it keeps going—but that is the beauty of Tex Avery. It is sheer self indulgence, purposefully seeking to grind the audience’s nerves, but not in a way that feels unwarranted. It is plenty obnoxious, no doubt, but remains justified through the visuals, the sound effects, the empathy and the story leading up to this point. It’s the ultimate culmination of long, belabored crashes heard off screen in many an Avery cartoon, including Of Fox and Hounds, which seemed to hint and lead up to this very moment through Willoughby’s spills over the cliff.

As the pan finally peters out to a trickle, a sardonic, “wah-wah” accompaniment of “

In the Shade of the Old Apple Tree” indicates that Willoughby is safe. We don’t see him, of course—the camera hasn’t even come to a complete stop yet—but surely a more grave musical choice would have been employed if he were in greater danger.

Sure enough, a befuddled, vacant yet unscathed Willoughby emerges from the wreckage of giant, heavy trees pinning his body down. It takes him a minute to absorb what just happened (as does everything), but the contented smile that stretches onto his face indicates that he’s taking it in stride.

“Uh-huh, uh… LOTsa trees!” Simple minded pride seems to blanket his words. To him, this mass destruction is a great accomplishment. Getting to crash into a ton of trees is much more rewarding than pursuing a quail. No quail could certainly do this.

Thus, we iris out on one last middle finger to the censors as Willoughby whistles (and razzes in spirit) in an attempt to blow his ear off of his muzzle. It’s the little things.

The Crackpot Quail isn’t exactly the end all be all of Tex Avery cartoons; it isn’t exactly as earth shattering of a development as

Of Fox and Hounds, and its successor,

The Heckling Hare, would refine many aspects of this short and take them to even greater lengths of exaggeration. It fits comfortably into Avery’s filmography—it entertains, it gets laughs, it impresses.

So, if this is what the norm looks like for Avery cartoons, if this is what is considered standard for him… then we, as the audience, could not be in better luck.

Indeed, it’s nothing short of amazing that the Warner studio is now able to produce cartoons that look as gorgeous and as funny as this one. A new precedent of quality is quickly being established all across the board. Acting is more full, more specific, perhaps even more empathetic. Yet, the actual art of animation itself—how drawings can illicit the feeling of movement and motion, and how that motion can be exaggerated—is rapidly growing as well. Now, the audience can laugh at the way something moves. Not just how it looks, but the movement it creates on screen. We can laugh at the uncomfortable amount of detail on Willoughby’s face, we can laugh at the absurdity of his run cycle, we can even just laugh at something as simple as his stares towards the audience. Rapid development of art direction gifts these cartoons with more opportunity to please, to amuse, to move.

Like so many of Avery’s shorts leading up to this one, the best aspects of this cartoon would be refined, polished, and exaggerated to even further lengths of absurdity over at MGM. Yet, the fact that this cartoon can even be compared to Avery’s MGM output at all speaks a great deal to its quality. The speed, the meta humor, the dynamic between wiseacre heckler and dolt “predator”, or the extravagance that is the last 30 seconds of the film would remain permanent fixtures of Avery’s vision and what he wanted from a cartoon.

Carl Stalling’s musical direction deserves a special shout-out. While there’s no such thing as a “bad” Stalling score, he does seem to be much more innovative and on his toes when partnered with Avery than with other directors at this point in time. His music is very much in tune with the action and the emotion—not just a backdrop to keep the audience interested. Chord combinations are inventive and comparatively unconventional, constructing a very specific tone that matches the warmly off-kilter nature of Avery’s cartoons. Stalling’s collaboration with Avery is proof that the director of the cartoon has just as big of a hand in informing how the music is approached as Stalling himself; that can amount to beautiful results, as is the case with this cartoon.

As luck would have it, the music catalogue for this cartoon survives. Note that the opening titles, merely listed as "Crackpot Quail", seem to be an original arrangement by Stalling himself.

The short primarily cycles through the same handful of music scores, but never once seems monotonous or drone-like. Stalling is able to transform the same piece of music into something completely new and independent given the context. Again, it’s nothing new, but deserves proper accolades.

A seemingly innocuous fixture in Avery’s filmography that might have the potential to be overlooked, this short is, if nothing else, a comfort. A comfort in that the studio is able to put out cartoons of this quality. Cartoons that are this funny, this subversive, this visceral, this gorgeous. With each passing cartoon, the definitive Warner style as we know it is closer and closer to being finalized. It’s thanks to cartoons such as this one that it can be finalized or even established at all. The acceleration of growth between all directors, not just Avery, is genuinely astounding. Almost astounding as Willoughby’s invincibility to mass destruction.

.gif)