Disclaimer: As can be surmised by the cartoon's title, this review contains racist stereotypes, caricatures, content and imagery. Though presented purely for informational and historical context, such defamatory stereotypes are wholeheartedly condemned. With that said, it is encouraged to speak up if I accidentally say something harmful, ignorant, or offensive--it is never my intention to do so and I aim to take accountability should that occur. Thank you.

Release Date: June 24th, 1939

Series: Looney Tunes

Director: Bob Clampett

Story: Ernest Gee

Animation: Norm McCabe

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Porky, Daffy, Guard, Dog, Natives)

Porky and Daffy mark their first official outing together of 1939, as indicated by a swanky new title card (regrettably) lasting a whopping 2 cartoons, Clampett's Wise Quacks being the other. Such demonstrates that even as early on as mid-1939--with only 4 other outings together previously--audiences and directors alike recognized the potential of the duo, their partnership solid enough to pose their billing as an attraction in itself. Their faces greeted theatrical audiences for years when serving as the default Looney Tunes opening title card, regardless of their involvement in the selected cartoon.

Yet another short riddled with defamatory anti-Indigenous stereotypes, Friz Freleng would remake this shot in 1944, rebranding it as Slightly Daffy and tracing a majority of the footage with the addition of color. There have been rumors (particular emphasis on "rumors", not fact) that Clampett originally started Slightly himself but got behind and had Freleng finish, which doesn't entirely seem baseless. For simplicity's sake, comparisons between this short and that will be more concentrated in the review of Slightly Daffy when we get to it.

Here, Daffy takes on the role of general, supervising the barracks where Porky and company occupy. When Native Americans hone in on the barracks, it's up to Porky and Daffy to save the day, especially after Daffy mistakenly swallows ammunition and becomes a real live assault weapon.

Per Clampettian tradition, a string of calm establishing shots lull the audience into a deceptive sense of security. Dick Thomas’ background work is lush and dimensional, a solid understanding of value scales granting shots depth with the foreground articles painted darker than the middle and background. Camera movements are still jittery upon their truck ins and dissolves, but not enough to be jarring.

Focusing on a sign advertising Post 13 (always a favorite unlucky number for cartoon makers), the “No dogs allowed around the post” addendum tracks with Clampett’s later concession that the sign gags were used as a cheat in the early days to get laughs when the motion of the characters itself wasn’t sophisticated nor funny enough to stand on its own.

As such, the dissolve to a literal guard dog pacing around the barracks makes for a subtle yet amusing tongue-in-cheek antithesis. While the inclusion of a dog in the post—directly refuting the adage on the sign—isn’t necessarily the point of the spotlight on either end, it certainly serves as a subtle bridge between the two. The sign is funny. The dopey dog pacing mechanically is funny. One could draw the connection between the sign and dog and get a laugh out of that, but it’s not necessary. A bonus is a bonus.

If the guard’s purposefully slow, aimless, weightless movements weren’t a solid indication of his stupidity, Carl Stalling’s discordant, childish accompaniment of “In the Army Now” certainly is. John Carey is the animator tasked with the dog’s introduction, the perfect casting choice thanks to his elastic, dimension animation. He could capture the weightlessness demanded by the dog’s demeanor that few others could, particularly strong in a rather aimless and arbitrary twirl from the guard, his ears smacking him in the face.

Carey’s elasticity and depth are each given their own highlights through wild head shakes and dialogue shots.

“Have you folks seen any Indians around here?” Blanc’s dopey drawl is perfectly on the nose, and Carey’s draftsmanship is infinitely appealing thanks to the tall, big eyes and soft, round face.

Clampett’s timing is slow enough allow the joke of the Natives filling up the scream and declaring in jovial unison “No, no, no, no, NO!” to be digested, but prompt enough to be abrupt and unpredictable. The mechanical head tilts seem to work in tandem with the artifice of their words, as though even their movements are disingenuous to reflect the lie. And, in spite of the mirrored animation for simplicity’s sake, the designs are varied enough to mask the cheat more effectively. On top of that, the dog’s regrettably brief yet mindless grin at the camera is a welcome addition.

His visitors exit in the same, mechanical glide that they entered. Mirroring both the entrances/exits and the animation itself makes the symmetrical movements feel like a design choice rather than an attempt to save time.

Dopey dog continues to share his words of wisdom. “Uh, that’s good.”

His dutiful walkabout resumes as we iris wipe to an interior shot of the post. Clampett uses a similar maneuver to one he employed in Kristopher Kolumbus Jr., where elements in the foreground are painted on their own layers and split into two opposing directions as the camera trucks in, an attempt to mimic the multi-plane camera effects most common in Disney cartoons for added dimension.

Stalling’s muted, drunken musical accompaniment paired with the “GENERAL DAFFY DUCK” sign outside the barracks create a deceptive narrative about Daffy’s role in the cartoon. By that point in time, audiences have been familiarized with Daffy enough to be aware of his screwball antics and incapacity—casting him as a general seems like a recipe for disaster. Crossed eyes, protruding tongues, hysterical convulsions and—of course—a hearty chorus of “HOO HOO!”s seem inevitable.

As such, Daffy’s entrance is purposefully dissonant as the door is thrown open and out comes marching Mister General himself, footsteps leaden, bearing a ferocious, commanding scowl as he sports a Napoleon hat—always synonymous with insanity or incompetence in these cartoons—and sheathed saber twice as big as he is. The scabbard's decidedly phallic appearance (especially knowing Clampett's adoration and track record of juvenile, priapic humor) is clearly no accident.

While Daffy may seem far removed from the character he’d later evolve to be, there are actually, believe it or not, a number of similarities already present to the duck that would dominate Clampett’s later cartoons. That is, a duck who is so committed to whatever role he is playing that he maintains the persona with only the utmost ferocity, even (and especially) if that yields disastrous results.

Speaking in Clampett terms, Daffy’s role as Danny Kaye and Duck Twacy in Book Revue and The Great Piggy Bank Robbery specifically come to mind, though it often extends to his own persona as a whole, regardless of imitation or lack thereof. Clampett’s duck is impulsive but impassioned, committed, and will tackle his priorities with the utmost devotion… until he either gets bored, distracted, or fearful and moves onto pursuing the next priority with the same energy.

Though this specific portrayal wasn’t unique to Clampett, it would certainly serve as a cornerstone for his cartoons. While Daffy may not have the sophistication nor depth of emotions here that he would later on, he’s certainly in the beta stages of that development. He appears closer to that than the mindless, autopilot insanity present in cartoons such as Porky & Daffy.

Daffy’s hunger for authority is realized when he stumbles upon a guard sleeping on the job. Though he hasn’t yet said a word, only skidded to a halt and glowered contemptuously, the audience immediately anticipates a bombastic response.

Contemptuous glowers and glances from left to right as though hiding from or stalking a victim cement Daffy’s theatrical-minded intentions. By now, he could have yelled at the guard to wake up and gotten him on his toes. Instead, the presentation, the theatrics, the ego is the priority. Mentioned previously in the The Daffy Doc analysis, Daffy in the early Clampett films often feels as though he’s role playing, mimicking the clichés and behaviors he’s seen or heard on film and radio, reveling in every second that an authoritarian status gives him.

Such is furthered when he reaches to unsheathe his saber, a rather extreme reaction to everyone but Daffy, who operates constantly at a rather bombastic, hysterical but not entirely unfounded logic. He obviously takes his role very seriously and wants everyone to be exceedingly aware of it.

Which is why—naturally—he unearths a puny dagger whose handle takes up half the length, again tapping into the phallic metaphor of his sheath. As has been seen before and will continued to be displayed throughout the cartoon, Clampett got a lot of use out of size disparity gags, especially when treating them with the same severity as its intended purpose. Indeed, Daffy struggles to unearth the dagger, the “SHING!” when it does come out demanding the same ferocity of an actual, large, deadly weapon. There is no wild reaction take as Daffy recognizes the puniness of the weapon. Maybe too long a pause, sure, but no wink at the camera or shrug at the audience. He works with what he has, and the audience is momentarily transported into his point of view, able to conceive the grandiose picture surely painted in his head.

Dreams of authoritarian grandiosity are maintained as Daffy prolongs the theatrics. Instead of stabbing the guard right then and there, he jabs the bugle hanging from his neck into his mouth and prepares to strike, armed by a climactic crescendo from Carl Stalling.

Obscuring the impact and cutting to the dog as soon as he gets hit makes the blow land all the more painfully; without seeing the dagger go directly into his behind, it’s up to the audience to fill in the blanks, purely depending on their overactive imaginations to inform the hit and imagine it being greater than it actually is. A hit or blow or impact on-screen can absolutely be dampened if the execution is mediocre, but the mind of the viewer will almost always make the hit feel greater than it is if left to their imagination, especially aided by strong sound effects or strong reactions from the receiver, as seen here.

Likewise, such an abrupt cut to the dog purposefully creates a jolt that mimics the sensation of the dagger landing in its victim, especially when said jolt involves the dog flying into the air and blowing out a fervent, rapid, high pitched rendition of Reveille in substitution of a scream. Allowing the trumpeting to be both fast and high in pitch, not just one or the other, further elevates the severity of the reaction. Judging by the spiral train lines left on the dog’s cap, Izzy Ellis may very well be the animator responsible of his close-up, though that’s more of a guess rather than a concrete observation.

To prolong the impact of the bugler’s trumpeting, Clampett cuts to the next piece of action with the Reveille still blazing in the background rather than waiting for the bugle to cease. Daffy now opts to put his authoritarian status to use, demanding the attention of his army.

“Get up, you guys! Whaddaya think this is, a rest home!?”

Animation of Daffy pumping his fists and yelling at the army isn’t exactly attractive, its awkwardness prolonged through the dissonance of Daffy’s back half staying on one static cel layer and his torso onward moving and stretching, making for a rather inorganic end result. Luckily, Daffy isn’t the visual priority. The fleet of soldiers barreling him down in a massive, synchronous crowd, aided through comically loud footsteps from Treg Brown, is.

As it turns out, Daffy’s ridiculously oversized sheath does provide a purpose: comedy. Once the mob finally leaves, Daffy, who has been buried beneath their trampling footsteps, reminds the audience of his presence as he reverberates back and forth, clinging to the sheath wedged into the ground. Shooting the animation on ones and employing dry brush rightfully create a relatively disorienting effect rife with energy.

Rather than engaging in another fit of hysterics and yelling about how his authority has been squandered, Daffy instead glowers at his army (but not after a rather awkward open-mouthed smile, its intentions unclear), still hugging the sheath. Interestingly, Daffy’s legs are colored a darker hue than his beak, a trend that seems to have started in The Daffy Doc and ending with Porky’s Last Stand. It’s seldom noticeable, but does stand out when his beak and legs are so close together in this particular shot.

As has been mentioned in previous reviews, Clampett excelled with variety in character designs, particularly when characters are clustered together in a shot. The differentiation and whimsicality in design appears to hit its zenith in the slow, crawling pan displaying the various denizens of the army. One soldier stands knock-kneed, another draped in a uniform much too big for him, his next comrade sporting a tattoo and a pronounced, spherical gut creating a wardrobe malfunction. One buck toothed, ambiguous animal makes up for his lack of size with a rather imposing harpoon. Even if the designs aren’t laugh out loud funny, they’re certainly interesting and engaging, if only for this shot alone.

Nevertheless, a wild, scrambling take from Daffy signifies that not everyone is present and accounted for. The take feels oddly staged, mechanical, as he does it in the process of turning to look into the barracks rather than as a result of laying his eyes on something, but it almost seems to work with his impulsive, unpredictable nature.

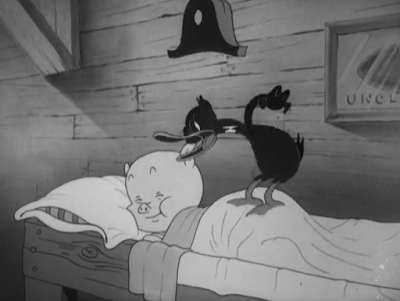

The straggler in question is none other than Porky, still fast asleep in his bunk. While the hilariously arbitrary and slightly supercilious “DO NOT DISTURB!” sign is the most glaring, other relatively subtle visual gags pepper the scene. A framed photo of a football labeled “UNCLE BUD” provides a more whimsical—if not equally cruel—spin on the framed sausage links labeled “FATHER” in Disney’s The Three Little Pigs. Likewise, Petunia’s inclusion in the cartoons grows more imminent, her photograph much more clear than the one near Porky’s bedside in Polar Pals. Porky’s Picnic, the next Clampett entry, would mark her return after a year and a half absence.

Daffy once again opts to take matters into his own hands, marching up to Porky’s bunk in tandem with Carl Stalling’s domineering yet playful musical accompaniment. A common occurrence in the black and white Clampett shorts, Daffy’s remark of “Ohhh, a slacker!” isn’t lip-synced properly in the animation. Whether or not it was on purpose or a line added in last minute, who’s to say; while it can be a distraction at times, Daffy is able to get away with it more than other characters, as it almost makes him feel a little more screwy, insane, an off-kilter choice for an off-kilter duck.

Humor in Daffy’s first forceful awakening of his bugler was derived from a physical contrast, mainly between the giant saber sheath and the puny dagger. Here, the emphasis is put on an emotional contrast. A commanding, accusing glare from Daffy suggests a verbal blow out or more violent means of waking Porky up.

Instead, he grows smitten. The eyelashes and rather pronounced, dainty fingers as he strikes an “ain’t that dear” pose are a wonderfully disingenuous and melodramatic addition. An ancillary design note: Daffy has colored irises for this scene, which were similarly present in a section from (presumably) the same animator in The Daffy Doc.

Said animator appears to be John Carey, particularly evident in Daffy’s prominently arched eyebrows, thin eyes, and glacial yet well constructed movements. A stark contrast to his earlier altercation with the bugler, Daffy’s attempts to rouse Porky are gentle and cloying as he coos “Porky… Porky…!”

Mel Blanc’s decidedly ear-shattering eruption of “PORKY!!!” is one of my personal favorite deliveries from Blanc and Daffy alike. The timing is sublime, a complete tonal whiplash that unfolds in less than a second. His screech is a bold, if not downright violent contrast to his soft tone just seconds prior, and even the physical act of him jumping into the air is much more direct and urgent in motion than any of his previous motions.

Continuing to ride the hyper momentum, Daffy immediately resorts to repeatedly jumping up and down on Porky, who refuses to budge. There are no downtrodden pauses or moments of contemplation that were present when Porky himself struggled to awaken Daffy in Porky & Daffy. No great realization, no sign of defeat. Instead, Daffy continues to act on his impulses, resorting to both verbal and physical harassment as he struggles to wake Porky up. While this sequence isn’t a direct callback or intended parallel to Porky’s similar attempts in Porky & Daffy, it certainly serves as a succinct and fascinating means of comparison, providing insight into how each character approaches a similar obstacle in his own unique line of thinking.

“Why dont’cha get up!? C’mon, Porky! Hurry up an’ get up! Get up quick! C’mon an’ get up, I said!” Daffy’s breathless, mush-mouthed hysterics, Carl Stalling’s comic descending, wilting music score, Treg Brown‘s repeated pap sound effects exaggerating Daffy’s hops, and Porky’s innocently rebellious expression of contentment as he refuses to stir are all necessary and very strong ingredients that make for a wonderfully funny, endearing, and energetic end product.

Ironically, Daffy himself falls victim to his own overzealousness, his rambling subsiding as he loses steam, jostles and jumps further spread apart as he tires himself out. “Dont’cha know it’s the early bird that catches the… worm…?”

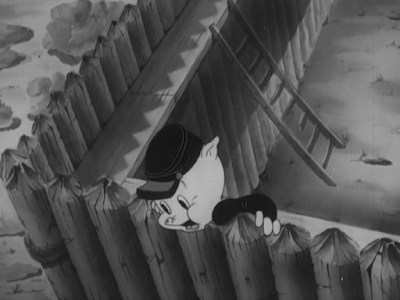

Porky’s cel changing for one single frame convey the impact he’s receiving as Daffy lands a final, weak blow is a very subtle but fulfilling and whole detail that is, in its own way, funnier than no movement from Porky at all.Nevertheless, Daffy subscribes to the maxim “If ya can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em”, showing little hesitation as he makes himself comfortable next to Porky. Remembering that this is a general in charge of an army (his pompous hat serving as a bloviated reminder) makes his surrendering all the more amusing.

And, as an answer to Carl Stalling’s facetious and increasingly climactic score of “Rock-a-bye Baby”, the cradle will fall. Carey’s animation of the bed buckling beneath Porky and Daffy’s weight strikes a solid balance between elastic and structured, so that the plasticity of the bed crashing to the ground doesn’t feel mechanical or lost in its weight, but not floaty and spacey either. The bed stretching before dipping out of frame, shedding one last glimpse at its occupants before crashing to certain doom, is a welcome addition.

Jointly, while the switch to a less skilled draftsman is noticeable with the rigidity of the bed crashing, the abruptness is welcome. The climax and build-up has already been shown, the suspenseful elasticity is no longer a priority. An alarming crash is.

On the plus side, Porky is finally awake, casting naïve, nonplussed blinks at a disgruntled Daffy, entangled in the “DO NOT DISTURB!” sign with his hat askew. Ironically, having Porky be positioned on top of a pillow and beneath a blanket still makes it appear as though he’s in bed, which adds to the unintentional coyness of his “Who, me?” expression.

And, unlike in Polar Pals where he was happy to oblige and enjoy his morning activities, Porky wastes little time scrambling out of his nightshirt and into his uniform, jumping vertically into the suit while it still hangs from the bed. Crude as some of the drawings may be, the spirit is certainly present, the presiding bounciness and rubbery movements rendering the scene in a soft, round sheen, the squat appearances of Porky and Daffy indulging Clampett’s occasional craving for cute.

Apologies are profuse as Porky gives a shaky, sweat-laden salute, sputtering out a handful of commands to indicate his loyalty. It certainly proves fascinating just how much Daffy has developed in so little time—he began as an obnoxious pest that Porky first tried to hunt, then grew to be an obnoxious but lovable companion who still needed Porky to tell him what to do in efforts such as Porky & Daffy. Now, HE has the upper hand, evidently maintaining enough authority to render Porky anxious. That hunger to prove himself as one who is autonomous and in control (or at least, “in control” by Daffy’s standards) seen in The Daffy Doc is certainly expounded upon here. Nearly 3 minutes in and not a single convulsion or “HOO HOO!” yet, which is certainly a new record.

Nevertheless, Clampett’s filmmaking grows more inspired as we cut to a shot of Porky and Daffy’s shadows projected upon the walls of the barracks. Upon Daffy’s command, the two march forward, their shadows snaking around in perspective, curving along one of the bunks in the background. While the bed is hardly in frame, obscuring the perspective tricks and saving them for last, its inclusion is appreciated and certainly gives an added authority to Daffy’s dominance. In this instance, he is clearly serious about his work—the filmmaking rightfully reflects that.

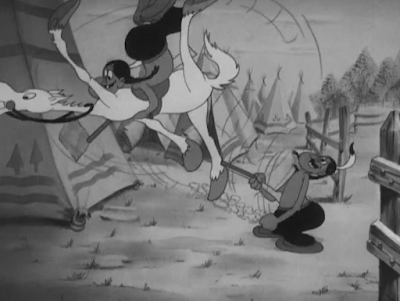

Unfortunately, even a simple march is a recipe for disaster. While Daffy merely disregards the sheath still lodged in the ground, upholding his pompous authority serving as the priority as he traipses along on top, Porky is an unfortunate victim of circumstance.

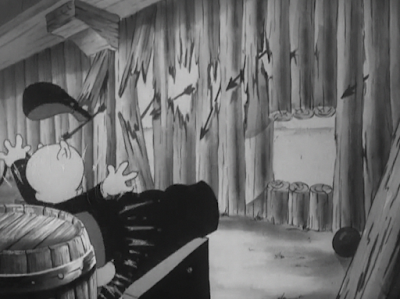

In Bob Clampett cartoons, it is law that simple, everyday objects (and characters, for that matter) must possess near lethal amounts of elastic properties. For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction. Therefore, Porky is propelled backwards with the same exact ferocity that the sheath exhibited when propelled into his face after Daffy stepped off the scabbard. Clampett doesn’t linger on the gag of Porky’s hat landing on the sheath’s handle in his absence, but it certainly lands as a bonus.

Thankfully—as has been harped on in previous reviews—Clampett knew not to inflict excessive pain on more endearing, sympathetic characters such as Porky, which is why the smack of the scabbard is more so a means of transportation than an injury. Still clinging to his harpoon gun, Porky flies back into the barracks, where the blade of the gun lodges in the floorboards.

With similar plasticity, Porky is propelled out of the barracks once more, the reverberations of the gun serving as the only indication of his prior presence. Judging by the synonymous wobbles when Daffy was clinging to the sheath reverberating in the ground earlier, either Clampett or the animators were particularly proud of finding a way to successfully depict a back and forth wobbling motion that felt convincing and jovial in its execution. Likewise, the cymbal crash as Porky’s gun makes impact with the floor, sending him out the door certainly exaggerates the various blows and hits and propulsions being withstood.

Enter the payoff in the form of a forceful collision. Daffy, still enraptured in his fantasy of being an authority figure, is completely oblivious to Porky’s absence nor incoming entrance. Once again a scene controlled by the hand of John Carey, the impact is rife with vigor, minor distortions (particularly the stretching of both Porky and Daffy as they make initial contact) exaggerating both the blow and motion.

While the assistant animation work on Porky and Daffy somersaulting across the screen verges on the crude side, the motion itself is the priority, not perfectly sculpted drawings. Likewise, the movement certainly feels frenetic, disorienting, aided by the camera pan matching the speed of their tumble through all parts of the process.

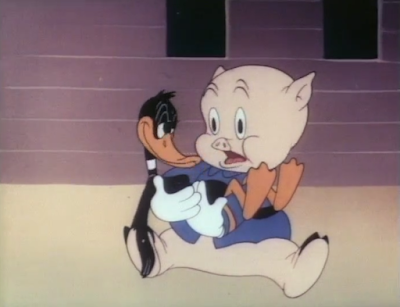

Then comes the true reveal; the somersault finally peters to a halt with Porky holding Daffy in his arms.

Similar to his earlier coy display during his initial attempts to wake up Porky, Daffy once again grows beguiled, blinking bashfully at Porky’s “advances”. Carl Stalling’s music score feels more earnest than it does mocking.

Daffy is the first of many to utter a catchphrase that would later become a recurring saying: “Gosh, I didn’t know you cared!”

While the maxim would continuously be used as a sardonic punchline, the sequence here is quite the anomaly in that it is incredibly earnest and, dare one say it, heartwarming as Daffy nuzzles Porky with coy giggles. That Porky reciprocates Daffy’s embrace is one thing; that it fades to black, ending on a genuine note, is another.

Looney Tunes certainly isn’t immune to its share of earnest, genuine moments, and Clampett has had plenty in his cartoon output thus far. Porky himself in Clampett’s hands is a vehicle for unadulterated earnesty. At the same time, Porky and Daffy are the only two characters who could ever get away with a scene such as this one and have it be passed off as a testament of their kinship—virtually every other character dynamic is vitriolic, antagonistic. Especially early on, Porky and Daffy are really the only two characters whose dynamic duo status is accepted as normal and genuine, and not a surprise case of “Look who teamed up together for a change!”

Even if this scene had been made 2, 3, 4 years later, it wouldn’t exactly have the same visceral sincerity; Daffy’s compact, cute design certainly makes for a more heartwarming watch than Porky struggling to hold the much leaner, more mature, wilier design of the ‘40s Daffy and onward. Even in this cartoon’s remake, Slightly Daffy, the effect isn’t the same with Daffy’s deeper voice and slightly more mature looks. Nevertheless, the sincerity is a welcome—if not fascinating—surprise.

.gif)

.gif)