Disclaimer: This review contains racist stereotypes, caricatures and imagery presented for historical and informational context. While these depictions are wholeheartedly condemned, I do encourage anyone to speak up if I happen to say something that is ignorant, harmful or offensive. It is never my intention to do so and I wish to take full accountability, should that occur. Thank you.

Release Date: May 13th, 1939

Series: Looney Tunes

Director: Bob Clampett

Story: Bob Clampett

Animation: Norm McCabe, Izzy Ellis

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Bob Purcell (Narrator), Mel Blanc (Porky, Sea Serpents, Native American, Queen)

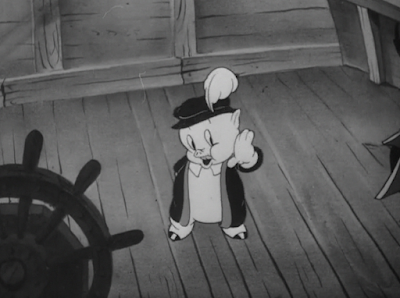

With the cartoon's song number delegated through the opening titles, Bob Clampett continues to latch onto his recurring motif of placing the ever-adaptable Porky in unfamiliar, fantastical surroundings as a polite but nevertheless eccentric explorer. Here, Porky stars as the eponymous "Kristopher Kolumbus Jr.", furthering the Hollywood, gentrified tale of how Columbus proved the Earth was round and discovered America.

Tedd Pierce lends his distinct deep voice as the short’s narrator. For the past year, he had been away at the Fleischer studio in Miami to work on Gulliver’s Travels as both a writer and a voice actor. He would continue to do a smattering of Fleischer work in the coming year or two, particularly focusing on the Popeyes.

In an interview with historian Michael Barrier, Clampett mentioned that he often used physical puns and still images as a way to garner laughs, as the animation in his cartoons couldn’t be depended on for its movement and mechanics. A number of these examples pop up in this cartoon, even at the beginning; typography labeled 1492 dissipates upon the black color card, accompanied by Tedd Pierce’s narration: “1492; when even the most learned of astronomers believed the Earth was flat as a pancake.”

Dissolve to a physical representation of the narrator’s description. Carl Stalling’s wah-wah music cue of “Long, Long Ago” provides ample sardonic commentary.

In an attempt to get artsy, Clampett provides a series of quick but dynamic truck-ins. Zooming into Spain (as conveniently marked on the pancake globe), the screen then dissolves to an aerial shot of a castle, with an overlay of some formless, relatively crudely drawn clouds quick to part ways while the scene continues to move.

An unscrewing of the lens on the camera akin to the transition seen in the “Starring Porky Pig…” titles is executed once more as a segue to the prize pig himself and the queen. Clampett gets a little slap-happy with the lens transition as the cartoon progresses, but it remains intriguing; he was obviously content at finding a new transition that wasn’t just a dissolve.

Whereas the animation could suffer in Clampett’s unit in terms of motion, the animation of Porky taking off his cap and bowing to the queen certainly does not. Aside from a quick cel layer issue, the mechanics move incredibly gracefully, the feather on his hat forming a smooth arc that neatly frames him as he bows. A slight head tilt towards the camera as he goes to grab the hat further establishes some depth to contrast with the flat, horizontal staging of the scene itself.

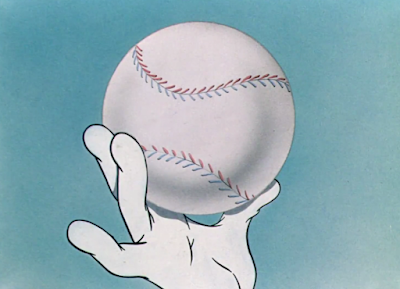

Consequently, the transition to Bobe Cannon’s handiwork is slightly more abrupt, the motion and clean-up work faltering in certain spots. Nevertheless, Porky dutifully obeys the narration (“Until, one day, Kristopher Kolumbus proved to the queen that the world was round,”) in a gag evidently so good that it would be reused in Bob McKimson’s Hare We Go 12 years later.

Stalling’s gentle accompaniment of Boccherini’s Minuet, Op. 13 No. 5 in E Major unifies the flourishes in Porky’s movements and greatly contradicts the comic, anachronistic nature of Porky pulling a baseball out of his pocket (marked with a close-up painting for good measure.) Cannon’s animation may lapse in draftsmanship—whether the fault of poor assistant work, clean-up work, or otherwise—but nevertheless follows a bouncy, back and forth momentum easy to follow.

Additionally, Porky’s showboating with the ball itself is great, rolling it along his shoulders, tossing it up with a flourish (with a small, brief, but potent smear in the ball enabling a snappy rhythm to the motion of the ball.)

Likewise with his wind-up for the pitch; rather than doing one rotation and throwing, he winds up once, gets in position…

…and winds up four times more, as if to fake out the audience and assert that no, the showing off is not over yet.

Moreover, the momentous suspense lingers even after Porky throws the ball. Armed with Treg Brown’s screeching sound effects, a climactic drumroll in the absence of a music score from Carl Stalling, and the camera tracking the ball’s movements as it crests a curve over the land and past the horizon (a curve serving as more dynamic, organic than a straight horizontal throw), the build-up is undisputedly playful, but not naïve in its execution. Silly as it may be, the suspense is certainly there.

A cut to Porky peering at the horizon is used as a bridge between two opposing directions. After he turns to face the opposite way, the camera glides right to make way for the return of the ball. Clampett clings to the suspense as much as he possibly can, as there’s a small pause before the ball comes streaking out of the hills and valleys, providing more natural, organic timing to its travels. Dick Thomas’ background work continues to deepen the perspective of the scene, with shrubbery in the foreground painted an opaque black to seamlessly separate the foreground from background.

The ball is quickly reunited with Porky’s grip, the impact nearly prompting him to topple over himself. Bobe Cannon’s animation possesses the necessary elasticity to stress the hit, and Carl Stalling’s crash of the cymbals further accentuates it with a mischievous flair.

Such an event prompts further flourishing for celebration purposes. While not anything incredibly elaborate, Cannon’s physics on the ball arcing over Porky’s head and how that timing differentiates with the timing of his little dance strikes an organic balance; the physics of the movement, even if the drawings and motion may not be the most elaborate, at least make an attempt to feel convincing, an attempt at unadulterated, symmetrical synchronization perhaps reading as too mechanical or stiff.

Of course, the mere act of the ball traveling around the world isn’t enough. To ensure that there are no tricks up his sleeve, Porky proudly displays the ball with the aid of a close-up painting, said ball smothered in stamps from all around the world as a memento of its travels. Once more, it’s certainly a silly gag, but one that seems unapologetically mischievous and playful rather than corny and contrived. As previously mentioned, Hare We Go would repeat the gag verbatim, complete with the exact same staging.

The queen is pleased, indicated by both the animation and Pierce’s narration. Composing the scene so that the queen can only be viewed primarily from profile furthers a sense of authority, stylization, as if her regality extends the logic and design of late ‘30s “funny animal” cartoons. A disconnect is obvious between the full movements of Porky and the stiff profile of the queen—contrast between human and pig furthers the juxtaposition.

As stipulated by the narration, the queen presents Porky with her crown jewels.

Cue another close-up painting of said jewels. The painting serves two purposes, one more clear than the other. For one, it's to reach the punchline—her crown jewels are nothing but cheap knickknacks. A pocket knife, slingshot, a “junior G man” badge, a 10¢ pearl necklace, a ring, a spoon, and even handcuffs. All of these trinkets are still displayed as though they are of the highest value—encased in a glass case, padded by a velvet cushion, intricate metalwork flourishing the wood of the box. Clampett was fond of his incongruous humor, and it certainly pays off here. The second reason (saving money by not having to animate anything) was surely something he was also thankful for.

Thankfully, Clampett alleviates any monotony from a long shot of a close-up painting by adding Porky’s voice in from off-screen: “Thanks, your eh-meh-mih-meh-maj-eh-mih-meh-mehh-mih-meh-eh-meh-ehhh—thanks, Queenie.” Already, Kolumbus is on much better footing than Chicken Jitters or Porky’s Movie Mystery, the humor in this delivery stemming from Porky and Porky alone, actually utilizing him as a character no matter how “cheap” a bait-n-switch delivery may be; no such luck with the previous entries.

“Came the day of departure. Kolumbus was prepared to face the dangers of the unknown sea, aided by his brave crew.”

Once more, Clampett is able to lessen his budget through lengthy narration and slow, scenic pans, this time panning past a tunnel and focusing on a shot of the ship docked at the harbor. Certainly there’s no issue with one utilizing narration or static pans in their cartoons, and here it works in the context, but given Clampett’s track record of going over budget in later years and struggling with the restraints of the black and white cartoons, his tricks and attempts to save a pretty penny grow more apparent. Nevertheless, the atmosphere he was attempting works well in this case.

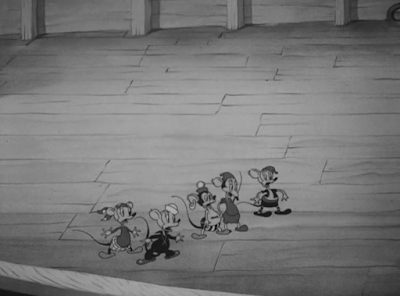

Besides, the somewhat pompous, stuffy historical narration serves as a wonderful incongruity to a shot of Porky and his “brave” crew; animated by John Carey, a number of bulbous nosed pirates huddle together, their knees a-clackin’ as Porky observes scornfully, Stalling’s score of “Blow the Man Down” successfully patronizing, comedic, childish. Cutting directly to the scene rather than easing in with a dissolve, fade or wipe enables the juxtaposition between the narrator’s words and the reality at hand to hit stronger. Any sort of transition would pad the blow too much to milk out the full amount of comedic potential. Cuts work best for contradictory compositions.

Back to Bobe Cannon, tacked with a dialogue scene for Porky as he usually is; “Weh-we-wee-why fellas! You’re not eh-see-eh-see-eh-scared to go, are you?” Blanc’s delivery is the perfect combination of innocent and condescending.

“Weh-wee-wee-what are you? Muh-mih-men or mice?”

An awkward, floaty pump of the fist asserts that Porky means business.

Pan left to the crew, an apparent switch in animators from Cannon to Carey marked by the designs of the crew and the fluid easing in and out of the motion. Before our very eyes, men turn into mice; the apprehensive glance shared beforehand serves as a nice bridge between the two scenes, padding the momentum and preventing any sort of abrupt transformation. Likewise, displaying the actual transformation—as opposed to a dissolve of the men turning into mice, and then a dissolve back to the men—elevates an admittedly corny but, again, forgiven visual gag.

Likewise with the squeaky, united declaration of “We’re MICE!” from the crew.

Cue another floaty, childish rendition of “Blow the Man Down” as the rodents scramble to dash out of the boat as quickly as possible. Carey was the perfect animator for the task—the mice are small and synchronized enough to read as one unit, easier on the eyes and less distracting than every single mouse taking a different route, but there’s also a potent amount of differentiation between the run cycles and scrambles to prevent any unionization from reading as stiff, mechanical, or cookie cutter.

Such is evident in one lone mouse who gets bowled over, serving as the straggler as the camera follows his departure, a pan down the plank making for some creative staging and overall furthering fluidity. As was the case with Chicken Jitters, Clampett storyboarding Kolumbus himself allowed for some relatively more innovative layouts and camera angles than what may be present in a cartoon where he didn’t board it himself.

Iris wipe to the next scene of action; hoisting the flag. The camera pans away from a mindlessly happy open-mouthed Porky manning the flag to the top of the ship. Clampett’s intriguing layouts are present not only in the diagonal composition of the shot, the exterior of the ship splitting the scene in half in a dynamic curve, but the gliding pan upright towards the crow’s nest, focusing on the flag soon to become unfurled.

An underwear joke solidifies Clampett’s unseen writing credit.

The underwear joke almost seems to purposefully underscore itself for the sake of the next gag, which is funny in 1939 and funny today in 2022. Pierce’s narration is jovial as he exclaims “[Kolumbus] left with the din of a tremendous farewell in his ears.” His “Listen to that crowd roar!” overlays the action of the pantaloons waving in the wind, attempting to cling to the build-up to the reveal and fake the audience out.

Faked out, the audience is indeed. While the smattering of crowd members lazing about on a set of bleachers beneath a “BUM VOYAGE KRIS” sign would be plenty funny in itself, particularly in the lackadaisical manner of the loiterers sitting around, what truly clinches the gag is the sound effect of an uproarious cheer from a crowd. No “wah-wah” sting from Carl Stalling, no cricket sound effects, no clearing of the throat from the narrator as he struggles to maintain decorum; the scene is structured faithfully to the narrator’s words, reflected in both sound effects and music score. As has been stressed in previous reviews, clinging to a gag and maintaining confidence in the concept and delivery spawns great things as we see here.

Back to a shot of the ship leaving the harbor, Pierce’s narration padding any monotony in the animation as the sails are the only thing in the scene conveying any sort of motion—the ship itself is a painted overlay.

With archaisms come modernisms, specifically contrasted together. Here, Clampett unifies old and new through the use of road signs and directions, the ship strategically skirting through them. Car horn sound effects and brakes squealing as he makes a turn further the illusion of the now modernized boat. Clampett would uphold a similar gag in his Pilgrim Porky by attaching bumper stickers to the stern of the boat.

A fade out and in works as a fine transition between day and night, whereas a dissolve or wipe seeming too abrupt or jumpy. An attempt to be peaceful, artsy, and theatrical is made through a horizontal wide shot of the ship bobbing along the nighttime waters, stars rife in the background. Stalling’s demure music score and Pierce’s gentle narration further the ambience.

Quietude and peace in an animated cartoon typically mean preparation for a gag, a juxtaposition, an explosion. Indeed, Clampett displays a literal, physical representation of Porky taking directions from the stars. The camera cuts from Porky peering through his telescope to a short of the telescope’s view itself, scanning the skies to pad out the reveal and further more organic timing.

Said reveal is granted by stars forming an arrow pointing left, the “TO AMERICA” beneath contributing to the absurdity when an arrow itself would suffice just fine. Carl Stalling accompanies the reveal with a triumphant score of “Dixie” to tie together the entire scene. Thus represents Clampett’s humor in the black and white days—when animation was too expensive or the limitations were too constraining, physical metaphors, typically in the form of a still, were the way to go. Clampett’s sign gags can verge on the corny side if not backed by the right amount of energy or devotion from the filmmaker, but here his wordplay is forgiven as there seems to be a general energy of excitement behind it, not a “we know this is bad and so will you” sort of throw-away gag.

Bobe Cannon is yet again tasked with animating Porky’s dialogue, this time as he makes a snide aside to the audience; “Jee-jee-jee-gee, I could sure muh-mih-mess up a lot of history buh-bih-books by turning back now, couldn’t I, folks?”

Porky coyly chuckles at the thought of putting a halt to mass colonization and genocide.

Dissolve back to the shot of the ship bobbing in the sea, once again underscored by Tedd Pierce’s stoic narration. “40 days and 40 nights passed…”

Once more, no matter how obvious (or not) it is that Clampett is hitting for gags within his budget range, using tricks and manipulating paintings, backgrounds, settings rather than squeezing animation or motion for comedic effect, the attempts that pay off pay off incredibly well, such as here. The joke is conveyed purely through a shifting of backgrounds between day and night, conveyed through dissolves, Stalling’s inquisitive music score, and Treg Brown’s electric guitar slide sound effects.

Slowly but surely, the transitions grow more frenetic: the piano accentuations marking the arrival of the sun and moon growing more rapid, guitar slides slurring together, dissolves between night and day turning into quick cuts. Soon, the scene is reduced to a rapid, flashing blur. It is genuinely disorienting. A flashing warning for the gif below.

“Hey!” The topper comes from an indignant narrator. “That's only 39!”

Again, rather than having the moon come to life and blow a raspberry at the narrator to tell him to buzz off, or merely just ignoring his words altogether, one final transformation between day and night is granted, comparatively slow next to the climax and enabling the audience to digest it perfectly.

“There.” Narrator sounds as though his livelihood was hinging on that single turnover, his tone almost slighted, condescending. “That’s better.”

With that, Clampett utilizes another blurring of the lens as a transition between two scenes, this time honing back to Porky studying a map. Synonymous to maps shown in similar Clampett cartoons, the topographic design here is full of whimsical touches and details, whether it be the dead end sign, the sea serpent territory, a whale in the waters, what looks to be like a palm tree obscured by Porky, and the fancy, checkered border snaking around the paper.

Upon the narrator’s foreboding warning about unknown perils, including “SEA SERPENTS!”, Porky returns the standard late ‘30s patronizing narrator dialect by condescending the narrator himself in his own naive, cute way. John Carey’s handiwork is easily identifiable by the constant motion, changing perspective and belabored blinks: “Eh-see-eh-sea serpents? Heh heh. Eh-thuh-thee-that’s silly.”

Clampett loved to play Porky as a befuddled innocent, particularly having him refute a character’s claim with good-hearted but oblivious dismissal, only for said claim in question to be proved right in his face. Carey was also responsible for a similar sequence in Porky’s Last Stand where Porky dismisses a panicked Daffy’s claims of a rampaging bull headed straight for them. Porky repeats the same routine even as late as 1946 in Kitty Kornered. That sort of innocent, accidental superiority (which ultimately backfires) makes him endearing and likeable, his dismissal coming from a place of oblivion rather than smugness.

“There’s eh-nuh-nih-no such thing as eh-sea serpents!”

Porky chuckles off the narrator’s claims, who remains silent. As such, it allows Clampett ample opportunity to pan out and reveal one sea serpents posing coyly against the ship. Assuming a relaxed stance is much more interesting, less cliché than a heaving, angry serpent snorting right in a startled pig’s face. Underplaying absurdity wins again.

For reasons unknown, Blanc voices the serpent with what sounds to be an Asian accent, dampening the enjoyment of the gag. Regardless of how insulting the dialect may be, the serpent asking if Porky thinks he’s “A priest? A poliwag?” is admittedly amusing.

Clampett loved to make his screwball characters effeminate at any given moment. The rapid eyelash batting is at least more amusing than any sort of slow, coy deliveries.

Ever honest and unassuming, Porky’s earnest reply of “We-why no! You’re not a-a poliwuhh-wag, you're a buh-beh-buh-behh...“ is funny purely through his sincerity, even if the vocal direction could use a more natural, less mechanical lilt to it.

In any case, Porky’s earnesty—endearing as it is—isn’t the focal point, but his screaming reaction take as his brain finally catches on is. Thus spawns some appealing, elastic frantic animation from Carey, Porky’s hooves glued to the floorboards of the ship in paralyzed anxiety. The animation is spaced and timed just right to enable a quick, cyclic, rubbery flow that succinctly caricatures Porky’s anxiety, but not in a manner that’s overkill.

To free himself and run away with no other flourishes would be boring. Clampett adds to the gag by making Porky tear a plank of wood out of the ship in the progress, disregarding it as he scrambles aimlessly offscreen.

Flaunting his layouts, Clampett pulls off an intriguing maneuver as Porky frantically scales the mast of the ship at lighting speed, a frightening piano glissando thundering in tandem with the camera snaking along the curved, vertical pan. The curve in the painting, the rapid motion of Porky scaling the mast, and Stalling’s hilariously frantic piano accompaniment all bring the scene together with a bold, quick, yet simple presentation that easily conveys Porky’s fear through anything but dialogue or facial expressions. He himself is difficult to discern with how quickly he climbs—the music, rapid motion and pan are the informants.

Taking refuge in the crow’s nest, Porky spares a trepidatious peek. Keeping him at such a small distance literally heightens his anxiety and lightens the mood, as a needless truck-in to a shot of his worried expression would be arbitrary and kill the momentum of the sequence. That the intent is conveyed so clearly at such a drastic distance is commendable.

Questions and debatable ethics of the serpent’s vocal origins aside, Blanc’s nonsensical deliveries of the serpent randomly bragging about he’s the biggest serpent in the “sea, sea, sea” is spirited and energetic enough to squeak out a chuckle. Really, the entire sequence of the serpent flexing his muscles is completely arbitrary—as is the next shot of a much larger serpent rising out of the water, Porky’s boat on his head as he grunts “Oh YEAH?”—but not unbearable. It doesn’t exactly serve many favors to the story and feels a little more random than most Clampett gags of the nature, but the overarching whimsicality is strong enough to be excusable.

Likewise, Porky’s ship remaining suspended in the air as the true biggest serpent pursues his aggravator calls attention to the absurdity of Porky being shanghaied during the altercation, as though Clampett acknowledges that he’s been purposefully sidetracked by these zanier figures. The physics and motion of the ship remaining in the air and flopping to the water sustains an elastic yet comfortable rhythm, serving as an adequate coda as the scene fades to black. That Porky is visible from the crow's nest is an endearing addition.

Fade in to a gag reused from Tex Avery’s The Isle of Pingo Pongo, freshened up by Pierce’s narration and the visual gag of Porky’s telescope writhing around in every direction.

“And then, when all looked darkest, on the horizon suddenly appeared…”

A rather flaccid landmass slaps the waters below it as it instantaneously flops on top of the surface of the water, similar to Pingo Pongo, whose delivery was much more straightforward and symmetrical—Clampett stresses the length and vast size of the landmass here, complete with a Statue of Liberty visible in the distance. "LAND!"

Dissolve and truck in from a jubilant Porky to the start of the Indigenous stereotypes. Such should be expected as such in a cartoon about Columbus, but remains uncomfortable not only in the negative depictions of the Native Americans, but the general ignorance of Columbus’ exploits and warping the story to treat him as a hero. Nevertheless, such is not the point here; anachronisms met with modern American landmarks are combined as they always are in these cartoons, beginning with the Statue of Liberty. A stoic statue of an Indigenous chief replaces Lady Liberty, scored by Stalling’s stereotypically bold musical accompaniment. Here, he holds cigars, a nod to Indigenous statues typically displayed outside of tobacco shops.

A vertical pan melts to one of the horizontal variety as a number of sign gags pepper the screen, once again alleviating animation costs and serving as a safety net for laughs where the limitations of the animation could not be trusted for jokes to land. One sign advertises “MANHATTAN ISLAND FOR SALE — 24¢”…

…the other squeezes as many tried-and-further-tried stereotypical, corny gags as it can. Even by 1939, these kinds of gags were growing tired. The whimsicality that preserved previous corny jokes in the cartoon is nowhere to be found in the execution of these sign gags. Racism or not, the camera lingers too long and the wordplay is uninspired at best.

Rather than dissolving immediately to the upcoming shot of a tourist boat gallivanting its way through the waters, a laborious camera pan continues before the dissolve is made, partially to maintain the scene’s “show-and-tell” momentum, other parts to pad out time.

Further cues are borrowed from Pingo Pongo in a close-up of the tourists on their “excursion to see the white men”. Upon Pierce’s cue of the natives wearing “their ceremonial headdresses in honor of the occasion”, Carl Stalling’s jovial music score of “Put On Your Old Gray Bonnet” slightly pillows the discomfort of the caricatures. With all of that said, the tourists are designed with typical Clampett fashion sense—long noses, big smiles, protruding tongues, crossed eyes. At the very least, the designs are varied through shape and size, as are their “headdresses”, which at least reduces monotony which would likely be much stronger had them gag been played straight.

The “official greeter” is introduced by riding along a wooden board in the water, outboard motor propelling him forward in a similar manner to Porky’s own island-turned-motorboat in Porky’s Movie Mystery. Striking the stereotypical sober, arms crossed, chest out pose attempts to rise comedy out of the discrepancy between the high energy of the “boat” and the unflappable stance of the greeter.

At the very least, the momentum of the board riding the water maintains a solid, swaying rhythm that is sustained in the wide shot of the greeter boarding the boat, flying up the ramp and landing onto the deck with ease. Staged as a wide shot adds more depth to the staging and remains more visually interesting than a straightforward sequence of cuts.

On that note, the cut between the wide shot and the Native approaching Porky does read as abrupt, not showing the greeter’s “recovery time” as he gets disembarks from his board. Nevertheless, Porky’s stuttering, appropriated greeting of “Hehh-eh-háu” is transformed into a vehicle for pop culture references by Bob Clampett. He maintains the stoicism of the greeter as much as he possibly can, whether through Stalling’s music score or the bloated, unflappable movements of the greeter as he too begins to raise his arm in greeting.

“How do you doooo?” The Native instantly turns into a caricature of Bert Gordon’s The Mad Russian, wiggling eyes and crossed eyes always synonymous with screwball antics. The appropriation of the Lakota greeting had already been widely stereotyped even by 1939, and would only continue from there.

Nevertheless, Clampett once again gets trigger happy with the lens blur transition, this time adding a fade out and iris in to hide the reuse. Like all Hollywood stories about Christopher Colombus, Porky is hailed as a savior. At the very least, the incongruity between 1492 America and a rolling limousine, raining confetti, skyscraper tipis, and even an aerial brigade boasts a whimsical energy through the blatant juxtaposition with the anachronisms. Even then, that scene only lasts for a few seconds, purely a vehicle for Clampett’s gags rather than a solid contribution to the story.

Rectifying the boisterous attitude of the previous parade, Clampett revisits a more artsy, sentimental route through the theatrical shot of the ship silhouetted against the starry night sky, bobbing gently in the ocean waves and lulled by Pierce’s narration. Now, Pierce indicates that Porky “took home” some of the Natives to show the queen as proof of his excursion. Similar to the opening, the narration clues that Porky was met with a warm, tremendous greeting.

The gag is admittedly less amusing the second time thanks to little to no change (perhaps a pure set of empty stands scored by the exact same cheering sound effect would suffice better, the lack of loyalty still present but the change surprising enough to reduce repetition), but remains difficult to dislike.

Dissolve to the queen’s palace, an attempt to be theatrical scored through the truck-in into the palace, the chandelier and pillar overlay in the foreground parting to deepen the overall composition.

Problematic as this entire half of the cartoon has been (seldom made better by the declaration of the Natives preparing to give their “ceremonial welcome”), Pierce’s narration has been a saving grace. Here, his jubilation over the prospect of the welcome is potent, his deep, pensive, if not condescending façade squandered through spirited deliveries. It certainly serves as a strong comedic antithesis to the relatively stuffy atmosphere of the scene at hand.

More stereotypes ensue, a shot of two Natives dancing reused from Friz Freleng’s Sweet Si*ux, the disconnect between 1937 Freleng and 1939 Clampett a little more obvious than other reuses. Clampett lulls the audience into a false sense of security, slowly bringing the sequence to a climax through a crescendo in drum beats and quicker movements…

…all so that he can lead to the self described “breakout”: a rousing, rowdy, undoubtedly Americanized jitterbug to “Jeepers Creepers”. Once more, problematic aspects aside, Stalling’s jazz rendition of the score is certainly catchy, and the shift in energy is certainly bold enough to accomplish Clampett’s mission.

Further scenes are delegated to Clampettesque denizens, such as a rotund Native using an exercise belt as a vehicle to dance, as well as a rather needless truck-in on Porky himself cutting a rug. While he could certainly stand a little more screen time (or, rather, productive screen time), Clampett attempting to remind the audience of Porky’s existence is not taken in vain. Kristopher Kolombus Jr. has its very hearty share of issues, but Porky isn’t one of them.

Nevertheless, Clampett—or, rather, the queen—puts a stop to the antics as she yells “STOP!”

Arbitrary as it may be, a short sequence dedicated to displaying the dancers immediately halting in their tracks is made amusing through the static pauses, Stalling’s deafening silence through lack of a music score, and a quick camera pan out during each scene, as though the camera itself is attempting to distance itself from the festivities.

Juxtaposition between the pompous, stuffy air of the queen and the cross-eyed, limber poses of the Natives is wonderfully strong. A lack of a music score, only a drumroll, makes the scene completely; much more threatening and daunting than any held out, low furtive music sting.

Porky visibly struggling to hold his own pose is genius in itself—all of the other dancers remain totally suspended in their poses, no matter the physics (or lack thereof) weighing them down. Through just the simple decision of making him tremble as he fights to maintain his pose, Clampett continues to ground Porky and make him a more endearing, sympathetic character, calling subtle attention to him by making him the only person in the palace to show a semblance of natural movement in that suspended moment. A physical manifestation of the claim that Porky is typically surrounded by zanier characters who exist in their own surreal, detached realms—with all of that said, sometimes the natural demeanors of someone like Porky is what stands out the most in such an arrangement.

Pontification aside (from the writer, that is), the queen studies Porky with an unwavering eye, doing little to alleviate his tremors as he struggles to hold the pose.

“Go!” Porky relaxes as soon as the queen speaks, which reads as a little too mechanical, synchronized, letting his guard down reading as more natural and effective after she finishes speaking, but it mainly serves as a vehicle for the next piece of business:

A dance off between pig and queen. As is usual, the juxtaposition between the queen’s comparatively realistic proportions and Porky’s own short, stout build serves humorous enough to iris out on.

As mentioned before, Kolumbus has a very fair share of issues, most stemming from racism. Any sort of Hollywood tale of Christopher Columbus, satire (such as here) or not is still doomed to fall into the pitfalls of painting him as a hero, a savior, and not a merciless genocidal colonizer. It may seem needless to point out the horrors of Columbus when dissecting a Porky Pig cartoon, but it does serve as something important to keep in mind, especially when viewing the parade of racial stereotypes and caricatures seen here. Just because the Natives are smiling and have crossed eyes and protruding tongues doesn’t alleviate the harm perpetuated by the stereotypes and caricatures.

With all that said, and by no means an excuse of any of the content, Clampett’s depictions here are at least somewhat on the more jovial side. There are dozens of other cartoons with Indigenous characters, both by Clampett and his cohorts, that are much more blatantly nasty and mean spirited—that the Natives here aren’t depicted as savages is a miracle in itself (though being depicted as gracious for Columbus’ arrival doesn’t fare much better.) While much of the content can’t be excused, the execution behind some of the gags is deserving of praise, whether it be musical choices (such as “Put On Your Old Gray Bonnet” during the headdress scene), composition, or certain camera maneuvers. The same applies to the mysteriously accented sea monster, whose deliveries seem to have an intent of lightheartedness behind them rather than active malice, but nevertheless remains questionable and uncomfortable.

In any case, Kolumbus fares much better than cartoons such as Chicken Jitters. Pilgrim Porky, made a year later in 1940, borrows a number of similar themes from this cartoon and suffers much more—any sort of saving grace through the lightheartedness and whimsicality present in this cartoon is hardly felt in the aforementioned short. While Porky’s screen time isn’t always milked to its top potential here, his presence is certainly felt and strings the cartoon together; such is not the case for Pilgrim.

Pierce’s narration is a welcome addition, his deliveries possessing a certain charisma behind them that other narrators such as Robert C. Bruce or Gil Warren, in spite of all of their talent, don’t exactly possess. Perhaps it relates to understanding Pierce’s background as a writer and voice actor in various comedic roles, but his narration possesses a stronger sardonic bite that gels well with the atmosphere demanded by this cartoon. Likewise, Clampett’s staging arrives in short but potent creative bursts, shots such as Porky scaling the ship’s mast in a hurry equally funny as they are engaging. The 40 days and 40 nights gag, as well as the baseball around the world joke, are both particularly nice gag highlights.

Nevertheless, Kolumbus is far from Clampett’s best, but not exactly his worst. There are a number of cartoons made in the same vein that are much more devoid of spirit than this one. While the racism prominent in the second half (and subject matter of the cartoon as a whole) bar it from any sort of solid recommendation worthy of a watch, there are little bubbles of energy or amusing gags dispersed throughout the picture that are at least admired in their effort to make the cartoon more bearable.

Link! As always, do tread with caution.

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment