Release Date: May 6th, 1939

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Tex Avery

Story: Jack Miller

Animation: Sid Sutherland

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Danny Webb (Killer Diller, Lone Ranger Announcer), Mel Blanc (Secret Agent 2 & 3/8ths, Lackey, Bank Teller, Audience Member, Cops), John Deering (Flat-Foot Flanigan), Tedd Pierce (Lackey)

Released 83 years ago to the day, Thugs with Dirty Mugs (its name a take on the 1938 Angels with Dirty Faces, already establishing the tone and background of the cartoon) is easily one of Tex Avery's best entries at Warner Bros. It poses as a reality-bending, transformative, cool headed but lighthearted lampoon of the ever popular gangster film genre swarming movies of the late '30s.

John Deering lends his voice to the film, playing the monotone, unflappable Flat-Foot Flanigan. He served as the narrator for Warners' The Roaring Twenties, a wildly popular gangster film released later in the year starring James Cagney and an up-and-coming Humphrey Bogart. His casting serves as the perfect mediator between animation and film; what better way to lampoon something than cast one of your characters familiar with the nuances of the source material?

Thugs follows Flanigan's pursuit to find the notorious Killer Diller, a dogfaced Edward G. Robinson caricature wiping banks clean of their money everywhere. Avery peppers the cartoon with incredibly unique gags, meta humor reaching heights like never before seen, all while executing it as smoothly and unassumingly as possible to make the gags land even harder. A true thesis into his method of madness.

That the cartoon is a parody is established even before the fade-in to the cartoon is finished. Mimicking the movie trailers and opening credit montages from the films of the time, Warner Bros or otherwise, the white typography overlaid on the action of each character swiftly introduces their roles with little meandering.

Each character receives their respective leitmotif; a triumphant fanfare of “Sing, You Son of a Gun” for Flat-Foot Flanigan (whose name has its own music roots, as indicated in the subscript), an alarming, apprehensive cue for Killer Diller, the connection between him and Edward G Robinson made as explicit as possible. Avery lingers on the scene of Diller robbing a bank to further stress his role in the picture (if the surname “Robemsome” wasn’t enough context.)

With crime dramas of the ‘30s come montage sequences, and Avery indulges heartily. Instead of dissolving to a shot of a newspaper headline or having it come spinning in from the center, he instead adds a jump cut, the abruptness purposeful and aided by Stalling’s powerful music sting. The energy in his filmmaking is felt exceedingly.

As such, to ease the audience into the flow of the transition, newspaper headlines stack on top of each other one by one; 1st National Bank Robbed by Killer. 2nd National Bank Robbed by Killer. 3rd, 4th, 5th, 6th, 7th. Slowly but surely, with each excessive headline thrown on top of the other, the pace grows faster and picks up the momentum, each accompanied by a sting from Stalling. Pertaining to the papers themselves, the same two designs are reused (a mugshot of Diller in one, a shot of a house and tree on the other) so as not to disorient the audience by making them ingest each new design for each incoming paper. Momentum is key. Headlines are key. Not the details.

Then comes lucky number 13. Avery places a slightly heavier emphasis on headline number 12 to indicate that the audience is to pay attention to the coming headline; the joke should be abrupt, but not disarmingly so. Red typography as opposed to black add extra support and importance to its punchline. With such a strong rhythm created by the previous 12 papers, the gag reveal here comes as an extra surprise and extra funny as a result.

Likewise for the papers that follow. Avery smothers the joke with more papers to pad it out from both ends; dissolving on the 13th headline and that alone would call too much attention to itself. It’s made to stand out, but there’s very little self importance in the delivery. Such is the genius of Tex Avery; as stressed in previous dissections, he was much more calculated, controlled, and analytical about his filmmakers than one may believe. Even “throwaway” gags such as these take a great deal of planning to land effectively, and that it does here.

As such, we segue to the goods. Avery’s mischievous spirit is very much felt in the presentation, but not so much that it’s a detriment; the dramatic upward angle perfectly balances the visual gag of the limousine accordion-ing into itself when it comes to a screeching halt—the staging is artsy, eye catching, but not to a degree of pretentiousness.

Killer Diller and his bandits peel out of the limo and into the bank. No dramatic truck-in and dissolve to the action unfolding inside: after a brief but thick, suspenseful pause, the gang emerges from the bank with guns a-blazin’, the car taking off down the street almost as soon as they pile in. Short, sweet, to the point, but bold and energetic. Avery’s need for speed has made major leaps in bounds just in the past year alone—even this pales in comparison to the lengths he’d take during his tenure in MGM. Either way, the content is easy to digest and still remains engaging all the while.

Now to a close-up shot of the car peeling into the back of the bank itself. Again, no such montage of the gang pouring out of the car and holding anyone hostage. Keeping the mood light, Avery obscures the action, filling any missing context clues with a shave and a haircut-adjacent drumline of gunshots. And, just as before, the car enters the bank almost as briefly as it entered.

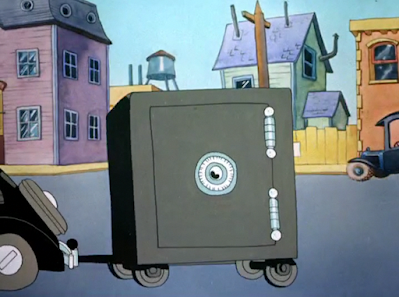

However, the mobsters are now armed with a giant safe, conveniently towed on the back of the limo.

While that in itself is absurd enough, Avery continues to seek for higher heights. In a gag that’s certainly no stranger to these cartoons, Avery births it new life by demonstrating the transformation between safe to camper onscreen. Right before our very eyes, the square safe morphs into a rounded semicircle, windows with awnings sprouting immediately. Whereas the visual of the camper itself would garner polite laughs had the car exited with that already as is (perhaps the words “SAFE” emblazoned on the front for any further clarity), the actual demonstration of the transformation is the real focal point of the gag. Seemingly arbitrary details such as the awnings on the windows further the absurdity.

Though perhaps a little slow, a shot of the limo rounding yet another corner is relieved of any monotony through flaunting a bit of perspective animation, the limo turning on its side for a few seconds. Urgency is slightly muddled through slower execution, but is still very well executed nevertheless, especially when the limo screeches to a halt.

Harkening back memories of cartoons such as Porky’s Badtime Story and Porky’s Railroad, just as the audience believes the limo is going to flatten itself into an accordion and stretch out again, Avery defies the expectations by allowing the limo to turn itself completely inside out, even facing the opposite direction for easy escape. Details such as a flower vase on the wall of the car or the pockets filled with papers once again adequately dress up the absurdity and further audience immersion into the gag.

Another swift robbery, now even without the aid of gunshots. Mobsters head on their merry way, aided by the convenience of their reversible limo.

With that, more lampooning of frequent montage sequences as the camera once again jump cuts to a newspaper headline: 87 BANKS ROBBED TODAY.

Perfect opportunity for a transition in mood. Although the camera dissolves to make way for more bank robberies, the next robbery is deliberately drawn out, the atmosphere furtive, suspenseful, sneaky rather than brash and alarming.

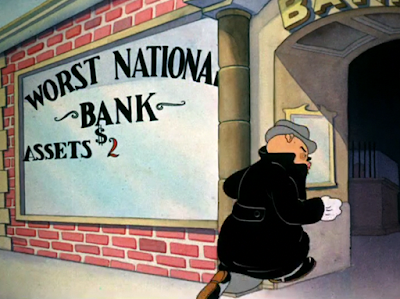

Consequently, the theatrics of the atmosphere serves as a greater antithesis and propellant for the imaginative gags to follow. Here, the car screeches to a halt in front of Worst National Bank, always a favorite pun. As touched upon in our review of A Day at the Zoo, Bank Nite refers to the raffles held at movie theaters during the Depression for the audience to win from a pool of prizes.

With great delicacy, from both Killer Diller and Tex Avery, the fire plug on the bank is transformed instantly to a pinball machine lever. While the transformation in itself could already suffice, what cements the engagement is the quick glances Diller spares at the bank, slowly pulling the lever, glancing back up at the bank to ensure that his hit will cover adequate distance.

Such menial little flourishes make a world of difference, all while miraculously not calling any undue attention to itself. Avery performed the same gag in Little Red Walking Hood in 1937, which was amusing as is—that he’s been able to refine the same setup to much more effective lengths in less than 2 years is incredibly impressive.

Likewise with the bank instantly turning into a pinball machine through the use of its façade and nothing more. Unlike the safe-turned-camper, there needs no physical metamorphosis from bank building to arcade game. Avery uses what he has—windows, fire plugs—and builds the transformation around any limitations, such containment furthering a sense of familiarity and thusly stronger immersion. A physical metamorphosis into a representation of the mechanisms being parodied would be fun, but to make use of the surroundings already provided and embolden the gag through that simplification is even more commendable. Carl Stalling’s quizzical musical accompaniment does wonders in conjunction with the blinking window lights.

Much like Walking Hood, Avery exhibits the payoff through a gradual sequence of diagonal tiles lighting up one by one. Suspense is built through the succession as opposed to having all panels light up at once.

Therein comes the true capper; the bank doors open to spew a swath of money bags right at the feet of the mobsters.

Their exit is swift and strong—no time to lose the momentous flow.

Avery continues to surprise the audience through jump cutting directly to newspaper headlines, rather than through a dissolve. As indicated by the bold type on the headline, the coppers attempt to close in on any and all suspects.

Our next bit of business would be borrowed almost verbatim in Bob Clampett’s The Great Piggy Bank Robbery 7 years later, right down to the silhouette obscured through the door’s window and dissolving to the interior of the office. Here, a copper grills into the suspect, heightened anxiety engrained in the obscured action and the officer’s threats of “If it’s the last thing I do, I’m gonna pin it on you.” Fear of the unknown ekes into the audience, as Avery employs their imaginations to fill in any and all missing blanks in the scene. Such an interrogation is made more gruesome by concealing it behind closed doors.

That is, until the camera dissolves into the office itself. Maintaining the same level of severity in his threats of “I’m gonna pin it on ya!”, Flat-Foot Flanigan waddles aimlessly through the office, blindfolded, holding a fake tail. A slow pan revealing the pin the tail on the donkey game clings to any and all vestiges of the gag’s build-up; to show the punchline right away would be criminal. Every last laugh must be treasured.

Whereas Clampett’s punchline placed a heavier emphasis on the game itself (and Daffy’s cheating at it, revealed by a shot of a visible eyehole through the blindfold), Avery embraces the slapstick route, having Flanigan aimlessly trip over a nearby wastebasket.

Though that could be enough in itself, Avery refuses to back down, going the full mile as the tail flies into the air and lands conveniently on the behind of Flanigan himself.

Fade out to an eye take from a befuddled chiefy.

Balancing out the lighthearted tone of the previous scene, we segue to a more furtive environment. With gangster movies come secret agents. Here, an anxious agent clad in a trench coat and newsboy hat struggles to get a connection on the phone. Much like Killer Diller’s deliberateness in his pinball ventures grounding the acting, the agent’s nervous jiggles and discernment mannerisms feel realistic… to a point.

As his alarm grows with the lack of a connection, so does the absurdity of his violence. Hushed “Operator! Operator!”s grow in volume, and fisticuffs are used as a last resort to get the phone to work, Treg Brown’s sound effects wonderfully scoring the abuse the phone is taking. His panic is realistic; the way he exhibits the panic is caricatured.

Said caricature reaches its zenith in yet another allusion to pinball; after withstanding a few more blows from the agent, the phone reads “TILT” after a brief orchestral build-up, indicating a malfunction. While Avery’s curt close-up to the flashing sign is overkill, it remains brief, and all the more forgivable.

Back to the headlines, this time: POLICE BAFFLED.

Easing monotony between transitions, Avery gets creative and uses the newspaper headline as a transition itself by peeling the paper away to reveal the next scene. Here, Flat-Foot Flanigan paces back and forth in his office, muttering inanely (“I’ll get that killer yet.”) to himself beneath a triumphant music score.

His lampooned routine of pacing mechanically back and forth to and from the foreground isn’t new—Big Man From the North all the way back in 1931 is eerily similar in its execution, with a hulking general turning his torso around mechanically before proceeding his walk. But, as to be expected from Avery, he elevates the level of caricature by allowing the cigar to float in the air after he leaves his assigned spot.

Smoke continuing to curl up into the air calls subtle attention to the cigar’s reality bending ways, but not enough to be distracting. Likewise, chiefy reacquaints it with his mouth with very little trouble, continuing to chuff pensively. As was the case with the staging in Big Man, allowing Flanigan to pace diagonally to and from the foreground in perspective rather than in a straight left to right loop provides a smoother rhythm and more depth, enabling the audience to immerse themselves in the gag even more.

Avery’s next source of parody is the ever popular split-screen, easing the monotony of phone calls in films by displaying two parties at once. Here, Avery’s subversion remains theatrical, creative, clinging onto the overarching mood of the cartoon by showing a rolling pan of the telephone wires as the mobster from before anxiously attempts to gain a connection.

Likewise, a brief flick of the cigarette ashes continues to ground this anxious caller, subtle, natural movements and acting decisions lulling the audience into the acting decisions in live action—all so that any and all subversions come as a greater juxtaposition and surprise.

At last, a shot of Flanigan brooding at his desk dissolved into the other half of the frame. Through hushed whispers, the caller introduces himself as Secret Agent 2 and 3/8ths, calling from Skunky Joe’s Beer Joint. As menial as it may be to point out, such ridiculous names are an art in themselves—2 and 3/8ths is a funnier number than, say, Agent 1 and 1/2. Skunky Joe’s Beer Joint is a funnier name than Joe’s Diner. It all relies on a level of absurdity and if the rhythm in the absurdity has enough momentum to roll off the tongue well.

“What? What’s that?” Flanigan maintains his chewy, gruff deliveries and demeanor.

“I say I’m calling from Skunky Joe’s Beer Joint!” Whispers continue.

At least until Flanigan puts a pause on them himself. While the gag here today of him physically breaking the boundaries between the call and demanding 2 3/8ths speak up may lose its novelty through imitations of the joke, it all had to start somewhere, and it was here it did. Avery’s straightforward and collected approach does the gag many favors, feeling naturally funny rather than trying aimlessly to prove itself.

To indicate that was the capper and that there are other fish to fry and suspects to grill, 2 3/8ths merely dubiously shrugs towards the audience rather than attempt to carry on the conversation.

Another newspaper headline slides on top of the scene, once again reducing any potential monotony through a dissolve or jump cut. Much like the Agent 2 and 3/8ths situation, “112th National Bank Robbed” is a more absurd and thusly more amusing number than, say, 30th National Bank.

Now a dissolve between scenes indicates a shift in momentum. Indeed, a silhouette of a car brakes to a halt along a dirt road, halting in front of a broken down shack. Johnny Johnsen’s background work establishes a lovely balance between light and moody shadows, color choices rich and maintaining a certain amount of warmth despite the cool color scheme.

Silhouettes of mobsters quickly file into the building, their bold shapes contrasting nicely with the comparatively light green of the background.

Camera trucks into the house as soon as the lights inside turn on. Avery ensures to note every little movement and detail to remain close to the source material of what he’s parodying. A certain eye for detail brings a bigger demand in this cartoon than others.

Enter Killer Diller and his gang. Diller’s Edward G. Robinson roots are cemented not only by his appearance, but his vocal performance as well, lampooned expertly and convincingly by one Danny Webb. The Warner directors would get plenty of mileage out of their Robinson caricatures for years to come.

Here, Diller sneers compliments as he shells out the dough, “seeee”ing his way through his assessment of the getaway. Throwing around cliched mobster names such as Rocky continues to cement the cartoon in the source material, the presiding irony lingering in the atmosphere rather than overexerting itself to make its presence known.

Unlike his imitators, Avery’s reality bending and acknowledgement of the audience never once feels condescending or flimsy in its structure. Here, Diller catches wind of the audience and is all too eager to get out of his chair and converse with us. “Saaay, folks, I kinda sound like Eddie Robinson, ‘uh? Yeah!”

Thus blossoms a completely arbitrary but gloriously so scene of Diller performing celebrity imitations. The scene has absolutely no relevance to the cartoon, which is the beauty of it. Diller spewing Robinsonisms would be enough as is, but he and Avery both continue to push the boundaries by Diller gloating “I can do Fred Allen, too!”

With Fred Allen having been obsolete for more than half a century, the relevance of the joke depletes to the modern 2022 audience. Thankfully, Diller’s impression doesn’t exclusively rely on the audience knowing who he is. While a viewer today may not know why Diller is holding a finger to his nose to sound nasally, reciting old radio catchphrases, they WILL know that it’s incongruous to the tone and will most certainly get a laugh out of one of Diller’s lackeys serving him humble pie: “Awww, c’mon Killah, quit show in’ off!”

Webb’s performance is wonderful—Diller chuckles a few times during his impression, as though he just can’t hold in how hilarious he finds his routine. As such, his glower as he reluctantly sits back down hits even harder. Even the scene itself abandons Diller, a quick fade out representing metaphorical curtains for his act.

Whereas this cartoon certainly feels much more like a string of events rather than one solid storyline, Avery pulls it off well, adequately contrasting the tones of each beat but stitching them together in an order that still allows for a momentous, smooth flow. Balancing out the recreational tone of Diller’s impressions, the camera dissolves to yet another heist, artsiness on the rise as the car speeds into frame from the foreground in solid perspective. A sign on the curb marked “RESERVED FOR GANGSTERS” adds a lighthearted flair and serves as a reminder that this is a cartoon, not a drama.

Paralleling Diller’s introduction in the cartoon’s credit montage, Diller demands that a dopey cashier fork over the dough, the pretentious and also slightly out of it half-lidded stare from the clerk dissipating in favor of a boggling eye take as a pistol is aimed straight at his face.

Averyisms commence as Diller stows the money away, his pistols remaining stagnant in the air in a very similar fashion to Flannigan’s cigar.

With an example of a “serious” (or at the very least straightforward) routine out of the way, Virgil Ross animates the antithesis. Mel Blanc eagerly voices an effeminate bank teller, living up to his title: “You’re a bad boy. I’m going to tay-ell! I’m going to tay-ell!”

Payoff is delivered in the form of a blow. After withstanding a conk to the head from one of Diller’s cronies, the teller’s head reverberates back and forth, his “I’m going to tay-ell!”s continuing with the aid of a delayed, dazed echo. A lack of a punch-drunk delivery works—only making his vocals echo to match his reverberations calls more attention to the absurdity through its straightforward execution. The teller’s head wobbles are much more sophisticated and better executed than anything attempted in Hardaway and Dalton’s Bars and Stripes Forever.

Another newspaper wipe to indicate the story marches on, now leading to a segment of the coppers grilling any and all suspects.

Similar to the shot of Flanigan's silhouette obscured through the door from his earlier grilling, the standalone shot of the office’s façade and nothing else shrouds the confrontation in apprehension—even if it is for a second.

Dissolve to the source of Flanigan's “Take that, you rat.” A joke that would flounder miserably in the hands of someone other than Tex Avery works miraculously and wholeheartedly embraces its stupidity. With each “take that!”, Flanigan tosses a thick piece of cheese into a large rat’s mouth. Allowing the rat to sit on an interrogation stool, under an interrogation lamp, underscores the hijinks by making it still fit into the context—he is technically still being interrogated! Avery even goes so far as to add a mouse hole in the background.

“And that’s all you get. I need the rest for my lunch.” The amicability between officer and rat truly bridge the gag together. It sounds as though this is an affair that occurs often enough to embark on a routine.

Nasally cries and tantrums from the rat serve as an amusing footnote as the scene fades to a close.

Avery reuses the earlier aerial shot of the limo scrunching up to a halt outside of a bank. Yet, in an attempt to mask the reuse, the camera trucks into the limo, serving as a bridge between scenes as the next shot serves as a close-up on Diller and the gang. He spots something offscreen.

$225,000,000 worth of assets to pilfer with little time to waste. A somewhat needless truck-in to the amount solidifies that the money is the object of Diller’s affections.

Woodblocks score the footsteps of Diller and one of his lackeys as the indiscriminately enter…

…and exit. No gunfire, no alarms, no screams, just bags full of dough. A teller whose Averyesque origins are strong in his design sense enters the scene, resigned to his fate by wiping the amount of money away.

Having a $2 as opposed to nothing at all is, once again, more amusing, calling more attention to itself but not in a way that feels pompous or unnecessary.

Furthermore, it serves as an additional transition to more antics. That is, Diller spots the remaining amount and is not happy. He opts to make quick work of the remainder.

Exiting the building with two large smackeroos in tow, he then wipes the window clean, paired with another truck-in of emphasis for good measure. The truck-ins are arbitrary, but last too briefly to serve as any formal criticism.

Another headline indicates that KILLER MAKES HAUL.

And that he does. More conventions are twisted in numerous way: twisting the source material of the parody, as well as subverting the pace of the cartoon. Whereas one may expect more shots of Diller robbing banks, he instead is confined to a phone booth and calling the operator.

“Number please?”

He provides his number in the form of a pistol, aiming straight for the phone. “This is a stickup, see!”

Jamming the gun into the mouthpiece serves as a strong substitute for the unseen operator’s face. “Shell out, sweethawt!”

Graphic lines emanating from the phone serve as a visual accompaniment to the piercing screams from the other line.

Jackpot. Once again, in similar manner to the earlier bank’s transformation into a pinball machine by utilizing the features already present, Avery transforms the phone into a slot machine by allowing coins to spew out from the phone’s slot, Diller all to eager to collect them in his hat. Avery’s utilization of what is given to him is solid—he doesn’t have to rely on physical metamorphosis gags or changes in structure to get his creativity across.

Another reused shot of the mobsters cramming back into their hideout. Avery’s recycling of footage doesn’t feel lazy or padded so much as it establishes a sort of ironic rhythm; the audience knows what to expect from both the cartoon and source of parody, there’s no need for any more elaborate shots of them heading back to the hideout. His reuse very much follows the mantra of “business as usual” with a slight comedic bite to it.

Staging the composition so that it’s zoomed out compared to its earlier appearance yet again masks any sort of recycling and tedium. Once again, Diller congratulates the “boys” on another job well done, dumping the contents onto their table.

Writer Tedd Pierce provides the gravelly growl from one of Diller’s honchos. “What’s da next job we’re going to pull?”

“Waitaminnit! I’m busy! Thinkin’!”

The acting in this cartoon is considerably more down to earth, with less demanding animation. As such, Avery is able to flourish in seemingly menial gags such as this one. Trying to stay true to the serious, grisled live action roots, any of the Avery unit's limitations animation-wise are masked, with the jokes spawning moreso from the environments and writing themselves rather than motion itself. As such, the contrast between Diller’s pensive expression and the literal translation of his words, a busy phone dial tone buzzing in his head, is spot on. Subtlety is key. Avery has a knack for making the subtle obvious through its subtle deliveries. Here is a great example.

A lack of a music score also further delegates attention onto the busy tone, which lasts for quite a few seconds, likely accounting for the laughter surely resounding through the audience.

Hardly a beat is skipped before Diller launches into his next scheme. “Dat rich dame on da hill! Missus Lotta Jewels!” Avery’s obvious wordplay carries an ironic bite and is much easier to forgive than when a similar name would be in the hands of someone like Ben Hardaway, who would almost certainly play it straight.

However, wordplay on Lotta Jewels is not the priority. What is, however, is the brilliancy unfolding on screen below, a shining gem of Avery’s Warners tenure. Established with Little Red Walking Hood in 1937, Avery has spun a number of variations on his gag of a silhouetted theater patron interrupting the show. One arrives late in Walking Hood. Egghead shoots another dead in Daffy Duck and Egghead. Cindy herself IS the silhouetted patron in Cinderella Meets Fella. And now, Avery stretches the gag as far as he can by having fake patron audibly converse with the stars onscreen.

“HEY BUD!” Diller drops his scheming and hashing out of any plans to focus on the silhouette making his way through the aisle. While the joke was surely a hit in a dark, crowded theater, it still lands perfectly today even on a TV, computer or phone screen. “You in da audience! Where d’ya think you’re goin’?”

Mel Blanc voices the patron, audibly anxious, the quaver in his voice just right—not too obvious, not to subtle. He attempts to reason with the mobster, stammering “Well, Mr. Killer… this is where I.. came in!”

Incredible acting on the silhouette, rotoscoping the action enabling the animators and cleanup to nail every little twitch and flinch and tweak. The synchronization between Diller pulling a gun on the poor sap and said sap’s reaction is sublime. “Well, you sit right back down there ‘til this thing’s over, see?”

A pregnant pause as the patron scrambles to sit himself back down perfectly compliments the setup.

Even then, Avery doesn’t drop it. Diller mentions to his lackey that the “mug” is itching to get out of the theater to tell the cops. Avery’s reality bending has always been immersive, but never to this length. Pulling it off convincingly is a very hard task. Imagining the shockwaves this sent through a 1939 theatrical audience is thrilling.

Indeed, the camera dissolves to said cop, Flanigan continuing to mutter to himself as he paces listlessly through the office. Flat, horizontal staging as opposed to the perspective flaunted prior indicate that an interruption is soon on the horizon. “If only I could get a tip-off on his next job…”

Said interruption arrives in the form of one anxious moviegoer. In a way, Tex Avery was not the first to have a moviegoer serve as a plot point—Frank Tashlin’s equally great The Case of the Stuttering Pig has an audience member lock the villain up after he repeatedly singles out the patron and makes fun of him all through the picture. The point of interest here, however, is that the moviegoer was never shown on the screen. No rotoscope silhouette, just the action onscreen and Mel Blanc as the patron. Here, Avery rides Tashlin’s momentum and combines it with his own sensibilities to make a wholly satisfying amalgamation of meta-humor.

“Oh, captain! I know, captain!“ Flanigan halts to listen to the patron, whose high strung vocals sound very similar to proto-Elmer Fudd’s deliveries as the pious peacemaker in A Feud There Was.

“I sat through this picture twice, and the Killer’s gonna be at Mrs. Lotta Jewels' at ten o’clock tonight!”

The suggestion that there’s an alternate of this cartoon where there is no audience interruption and where the copper doesn’t get a tip-off is endlessly amusing. Flanigan is grateful, spewing a quick thank you before heading out the door.

Or so we think. A character leaving a scene, then visiting again, then leaving once more has been an Avery staple for years now, but never to this degree. Even the meek-minded patron is not safe from the scorn of the “good guys”; “You little tattletale!”

A fade out to black serves as a strong coda to the sequence. Onto the scene of the crime.

Johnsen’s backgrounds continue to assert themselves as picturesque but not to a degree of pretentiousness. A cluster of trees frames a sliver of a yellow moon, harmonizing with the glow of the yellow limo headlights and yellow light of the mansion inside, while also reflecting off the rich, moody blues, greens and purples dominating the scene. An overlay of the headlights dimming as the car comes to a halt is a straightforward yet welcome accompaniment.

“Quiet, you mugs! Wait’ll they put out the lights.”

Plink! The lights all go off in conjunction with Stalling’s furtive music score of “Jeepers Creepers”.

Of course, being Tex Avery, he manages to slip a bathroom joke under the noses of the censors, indicated by a single light briefly turned on and back off again as business is tended to.

Dissolve to the bandits quietly creeping through the mansion. The manner in which their shadows are so boldly broadcasted upon the wall, each mobster walking in perfect tandem with the other, harkens back to similar staging in Avery’s The Mice Will Play.

Whereas the shadow gag in that cartoon was a highlight in itself, Avery continues to top himself by playing it cool and straightforward. Complaining about the volume of Stalling’s musical string pluck footsteps, Diller surmises that the shadows stay back and keep a lookout while the physical beings go on ahead. Explicitly addressing the shadows AS shadows further stretches the bounds of Avery’s meta humor—he doesn’t try to sugarcoat anything being presented. The shadows are sentient and being talked to.

Such is furthered as the shadows nod obediently, scored by sardonic violin slides.

Thus births the true payoff; hearing Diller command the shadows is funny enough as is, but actually viewing his plan in motion, the camera panning past the motionless shadows and essentially abandoning them, is pure genius.

Many of Avery’s gags follow an A-B-A pattern. That is, one motif is established, then another (often one that contradicts the first), and whenever that business is taken care of, the first motif is revisited with any revisions demanded by the second motif. Here, the walk cycle of the monsters is A. Diller halting the shadows and telling them to stay back is B. Diller and gang resuming the exact same walk, only this time WITHOUT the shadows, heads back to A again. The formula is basic, but provides a strong and satisfying symmetry and rhythm, easing the audience into the action and accustoming them to what is happening and what is going to happen. It is then why the subversions are such a welcome surprise, as the audience knows what to expect, and watching the setup they’re accustomed to paired with the aftermath of said subversion makes any and all absurdity all the more prominent without actually calling exceeding attention to itself.

Resuming the theatrical staging, another moody up-shot of the mansion’s interior continues to ground the cartoon to its source. Live action cues are taken not only in the acting and setting, but the staging as well. Likewise, the flashlight circle growing smaller as the gang approaches from offscreen certainly feels very realistic. Coppers entering from the foreground and framing the approaching monsters connect the entire piece together and establish a gorgeous flow of movement and action. Like a domino effect, every little movement, every character, and every bit of staging is all connected and impacts the outcomes of the others.

Wonderful apprehensive acting from Diller and the gang. Sneaky glances (ranging from flicks of the pupils to turns of the head), pregnant pauses, and even a beat delegated to Diller rubbing his gloved fingernails on his jacket all immerse the audience into the source material. Again, Avery’s eye for detail is particularly sharp in the acting decisions in this cartoon.

Thusly, the quietude and heavy atmosphere serve as the perfect segue to another tonal shift. This time, Diller turns the dial of a safe like a radio dial, Treg Brown’s radio frequency beeps and hums pivotal to the success of the illusion. Worth reiterating once again, the transformation from safe to radio isn’t dependent on any sort of physical, outward metamorphosis. Avery makes do with what he has.

A Lone (St)Ranger broadcast triumphantly blazes on the newfound radio. Rather than getting frustrated and turning the radio off, then trying the safe again, Diller and his lackeys crowd obediently around the radio, sporting elated grins as they situate themselves on the ground like a swarm of 5 year olds. Avery playing this off as though the radio broadcast is the true source of their mission is positively brilliant.

But, of course, the cops are still lurking about, and to end now would be futile. Dramatic composition resumes as one of the coppers turns the lights on, the others aiming their rifles and demanding the mobsters stick ‘em up. Diagonal angles, tall perspective and elevated sense of height all contribute to an overarching flow of motion and dynamism in the scene.

Perspective continues to be flaunted as the coppers make their way down the landing, each honing in on their own suspect to focus on. 3 for 3 is the perfect number: 4 is too even, 2 is too little. One of the lackeys’ jacket being gray while the others sport black on either side establishes a fine symmetrical balance between the hoodlums.

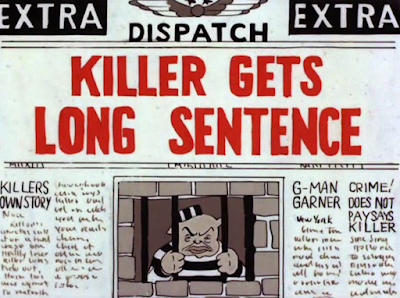

Enter one last fleeting newspaper montage, headlines of “KILLER CAPTURED” and “KILLER CONVICTED” met with an alarming music sting from Stalling.

Avery saves the classic newspaper spin for very last, the inking and handwriting on the paper considerably looser and less structured than the other close-ups. G-Man Garner serves as a nod to camera operator Smokey Garner. A snapshot of Killer Diller behind bars, as well as the headline typed in a screaming red, cement finality to story.

Killer’s long sentence is given a literal meaning as the camera dissolves to a patronized prisoner writing sentences on the chalkboards conveniently provided in the jail cell. A striped dunce cap is sublime accompaniment—it seems his childishness towards the Lone Ranger isn’t as surface level as originally thought.

Stalling’s minor key orchestral fanfare is a wonderful accompaniment to Diller sticking his tongue out at the audience at the very last minute.

Thugs with Dirty Mugs is easily one of Avery’s best cartoons during his tenure at Warner Bros. He embraces and relishes the world of meta humor, stretching the bounds farther than he or any of his contemporaries have dared before. What comes off as funny even in 2022 was once riotous and truly groundbreaking, absolutely unlike its kind back in 1939. There was no “Tex did this gag better a few years later” back then, which is incredibly important to keep in mind. That he was able to warp the comic bounds of cartoon reality, whether it be a glance at the camera to a theatergoer essentially saving the day, not to mention warping it clearly and successfully, is quite the accomplishment.

Lampooning the gangster pictures of the era provides an excellent springboard in numerous ways. For one, the slow, often lugubrious atmosphere of these live action films mean that Avery doesn’t have to think of attuning his animation style to fit the needs of high paced hijinks so prevalent in all of his other cartoons. Here, he’s able to focus on every little subtle movement, every glance or flick of the finger, allowing more time to focus on solid animation and design because one doesn’t have to think about the distortions needed by certain energetic beats.

Furthermore, Avery is able to subvert what the audience is already quite acclimated to with ease. There doesn’t have to be a laborious set-up of “this is a mobster, and mobsters are bad, and they steal money and have gangs, and there are title sequences and newspaper headlines, and this is a cop, the cops are seen as the good guys in these films,” etc, etc. Avery is instead able to swiftly address on each and every cliché while trusting the audience recognizes it as a cliché. Little time is wasted beating around the bush or getting to a certain point.

Thugs is absolutely a cartoon worth delving into. While Avery would continue to refine his speed, pacing, and execution in coming years, this cartoon is certifiably his Warner Bros peak for at least the next year, and still holds up incredibly well. Very little problems drag the cartoon down, if at all—at most, a punchline may prompt a truck-in of the camera that reads as arbitrary, but even that is quick at best. From the transformation of comic objects into fantastical scenarios to cool, collected but incredibly hysterical meta humor, Thugs is an Avery masterpiece whose artfulness can be appreciated from all angles regardless of the time period.

.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment