Release Date: May 20th, 1939

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Chuck Jones

Story: Rich Hogan

Animation: Phil Monroe

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Margaret Hill-Talbot (Sniffles), Mel Blanc (Hiccups)

A new era is turned in the realm of cartoons directed by Charles M. Jones with the birth of Naughty but Mice. Jones introduces his first fully fledged star and a figure synonymous with his work from the period: Sniffles.

Sniffles was a collaborative effort, not only from Jones, but from his animators and Carl Stalling as well, all doing their part to birth life into the mouse and leave their own imprint. However, two voices are particularly worth mentioning in the success and birth of Sniffles: Charlie Thorson and Margaret Hill-Talbot.

By 1939, Warners was still attempting to cling to the successes of Disney, though the influence was not as prominent as it once was. Either way, it was enough for Leon Schlesinger to brag about in the Hollywood Reporter upon the acquisition of former Disney employee Thorson; "Charles Thorson, formerly with Disney, has been signed to a five-year contract by Leon Schlesinger as a character model man for Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies."Thorson designed Sniffles for Jones, his design sense most concentrated in the Jones and Hardaway/Dalton efforts. While he wouldn't even go on to last a year of his five year contract, his influence was strong, especially in crafting the Disneyesque sensibilities Jones was craving for so long. Sniffles' design is, at its core, a slight variation of Abner Countrymouse of The Country Cousin fame (who also gets drunk in the aforementioned cartoon, a significant plot point in Naughty but Mice). Nevertheless, Thorson's design sensibilities brought the exact cute charm that Jones needed for the character, and serves as a major proponent of his success.

The other major contributor to Sniffles' legacy is his voice actress, Margaret Hill-Talbot. Throughout his career, Sniffles would be voiced by Talbot and later Marjorie Tarlton, yet Talbot was the one responsible for establishing his soft-spoken yet charismatic manner of speaking. She could be funny just as she could be cute, but the latter proved to be the presiding factor.

Nevertheless, Sniffles' conception finally allowed Jones to have a character of his own, and one he could fall back on. It took until 1946 to fully retire Sniffles, long past the days of the Disneyesque sensibilities peppering Jones' shorts. Even then, he was rebranded into an obnoxious blabbermouth in the brilliantly funny The Unbearable Bear in 1943, quite a step away from the comedy achieved by his genuine, soft spoken mannerisms exhibited early on.

While the Sniffles cartoons certainly had a bad habit of bloated timing, Naughty but Mice's sluggish pacing is purposeful and works well with the plot: searching to alleviate his cold, the medicine with a 125% alcohol content is quick to go to Sniffles' head. In the midst of his drunken stupor, he befriends an electric razor who serves as a key figure in saving the little rodent from the perils of a hungry cat lurking nearby.

An instance where the title card art serves a functional purpose to the cartoon, typography dissolves to make way for a moody nighttime pan initiated after the drone of the clock tower striking.

From vertical to horizontal, the camera glides across the empty city streets, Carl Stalling’s muted accompaniment of “Deep in a Dream” uniting well with the rich, cozy hues and colors employed in the background paintings. Per the late ‘30s norm, an Art Deco influence is potent in the sleek stylings of the buildings and the neon lettering snaking the storefronts. Round street lamps in the foreground and curving buildings rounding into the horizon deepen the composition, especially once the camera halts on a drugstore shot at a diagonal angle.

A truck-in and dissolve designates the front door as its target, “DRUG STORE” lettering emblazoning the window glass to ensure the audience recognizes these new surroundings. Never one to rush things during this period, Jones’ camera pans are slow yet atmospheric, fitting the sleepy ambience of the empty streets. Appealing background paintings and comfortable musical accompaniment go a long way to sustain audience engagement.

At last, the camera finally comes to a halt in order to introduce Warner’s newest rodent star. Enter Sniffles, peering up at the towering door with some sort of paper in his hand. Stalling’s musical accompaniment morphs from muted to brazen, brassy, a rather aggravated trumpet solo indicating Sniffles isn't at his current destination without reason.

His cause is revealed through another shaky truck-in and dissolve. Sleepy, squinty eyes, agape mouth and a handkerchief in tow already paint a picture of his condition with ease, but a sneeze into said handkerchief secures his ailment. While the audience at this point is unaware of his name (as it had not yet been known by this point), the context clues point to the right direction.

Bloated movements further solidify Sniffles’ condition and the audience’s sympathy therein as he glacially raises the paper to eye level. Jones’ natural slow pacing serves a purpose in this case and is almost encouraged, a functional source of personality for Sniffles’ condition rather than a technological or directorial shortcoming.

The ever reliable close-up painting informs the audience that the slip of paper is a torn advertisement for cough syrup, directing its readers to the nearest drug store. That Sniffles appears to have torn away an unrelated section not only allows the audience to give their undivided attention to the cough medicine pointers, but further gives both the paper and Sniffles some unseen character. A story is told; Sniffles saw this ad in the local newspaper, tore it out for safekeeping, and embarked on a journey to find said nearest drug store. Rather than neatly ripping out an entire page, where other sidelined articles could serve as potential vehicles for gags through nonsensical headline titles, Jones ensures the audience is sold on the intent.

Instead of doing a jubilant, zipping take inside, overjoyed at finally discovering a cure for his cold, Jones continues to restrain himself by having Sniffles laboriously stuff his handkerchief in his pocket, discarding the news clipping as he utilizes the mail slot for a way to get inside. Once again, it bears repeating that the pregnant motion exuded by Sniffles is a purposeful decision and not the result of directorial inexperience. Movements such as the handkerchief stuffing or the slow crawl through the slot are certainly much more deliberate than any sort of pacing issues present in a cartoon such as Dog Gone Modern.

Furthering the ambience, a moody interior shot of the unoccupied drug store serves as both a bit of atmosphere and a transition between scenes, another uneven truck-in and dissolve delegating focus to Sniffles’ exploration inside.

Whereas the shift to a lesser animator is certainly noticeable in the comparatively less constructed head tilts, Charlie Thorson’s design sense becomes exceedingly prominent in a profile shot from Sniffles. Slightly tapered eyes, lowered chin and an overall compact construction look straight out of Thorson’s drawings.

A reaction take from Sniffles quickly divorces itself from Thorson’s controlled drawing style as he catches wind of something offscreen. His hat take becomes slightly obscured through the graphic “excitement” marks, the cap falling back to his head with little fanfare, but it at least attempts to convey the rodent’s jubilation.

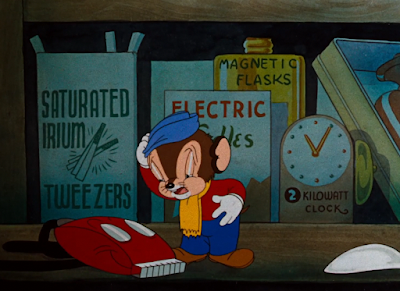

As such, an intricate weaving of camera pans is in order. Rather than panning through the interior of the store and dissolving to the object of Sniffles’ delight, the camera instead snakes through the drugstore like a maze, providing a quick glimpse of the goodies inside. Panning horizontally past a glass counter, the pan turns vertical, grazing past various jars and bottles and toiletries stored inside the counter, only to halt and truck-out on a shelf conveniently labeled “COLD REMEDIES”.

Organizing the various remedies on the shelf in neat rows, the labels on the bottles synonymous with each other and each bottle clustered closely together, the contents of the drug store appear more plentiful and concentrated than they may actually be. Busyness in the background details serves a purpose, but continues to delegate ample attention to Sniffles as he scales up the shelf and meanders along.

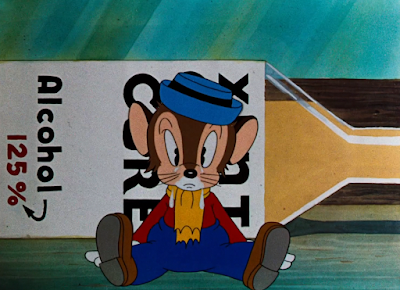

A few tottering steps forward allows him to finally stumble upon the object of his pursuits: one bottle of “XLNT COLD CURE”, the “Alcohol 125%” boldened at the bottom to inform the audience that the number is worth looking into. With an alcohol volume of 125%, the remedy seems to live up to its self proclaimed excellency. Again, Jones continues to keep Sniffles grounded, displaying his excitement in small bursts. Instead of rushing to open the bottle right away, Sniffles takes a moment to read the bottle.

Then comes the excited take.

All of the materials required for Sniffles to ingest the medicine are conveniently nearby. Having him haul a bottle off the shelf and stumble around the counter, struggling beneath its weight, repeating the same charade as he attempts to find a nearby vessel to ingest the liquid from would fall into the monotony that plagued cartoons such as Dog Gone Modern or The Night Watchman. Understanding that isn’t the intent of the scene, Jones allows Sniffles to tip the bottle over with ease and pour it into a nearby spoon propped up into a secure position. “Cheating” the convenience of the readily available materials serves as a strength in this case, and not a weakness or directorial oversight.

While Sniffles may not be a riotous, vastly recognized and praised character today, one can understand why Jones wished to use him as much as he did; mannerisms such as holding his nose before infesting the remedy continues to birth appealing, endearing quirks that point towards Sniffles’ personality, waiting to be chipped out as the cartoon progresses.

Now for the medicine to take effect. Jones’ staging does an excellent job of seamlessly directing the viewer’s eye to Sniffles; the wood stretching along the glass counters in the background all frame him, the bottle of medicine, the spoon, and the articles behind the glass cabinets forming a vast negative space that encourages the audience to look at the positive space inhabited by him.

A jump to a closeup of a dazed Sniffles subconsciously cues the audience that a reaction is broiling behind the scenes. Any sort of shift between scenes indicates a change is about to happen.

Here, Jones approaches the change slowly, milking the atmospheric stillness to its advantage. A belabored blink from Sniffles is topped off by a metaphorical visual of his stomach heating up. The double exposure effect works very well—in spite of some flickering on the screen, there’s very little blurriness or miscommunication between cels and camera that plagued cartoons such as The Night Watchman.

Thus builds up to a explosion as the liquor literally goes to Sniffles’ head, out his ears, and back to his gut in a delightfully elastic and—for 1939 standards—wild take. Jokes about alcohol and its potency were certainly no stranger to Warner Bros cartoons, dedicating some of its earliest cartoons to blatantly disregarding Prohibition standards. However, not a cartoon yet has depicted a more rousing metaphor for the fiery effects of alcohol with the amount of sophistication, control, and energy as is displayed here. While the rubber hose cartoons of the ‘30s showed dogs burning their torsos after ingesting a swig of hooch, the appeal and draftsmanship has never yet been met as it is here.

Instead of allowing the drunkenness to rush to his head all at once, Jones continues to stress the alcohol’s strength through tears (emanating realistically from the inner corners of the eyes at that!) and awestruck breaths of fire.

As is typically the case, Bob McKimson is tasked with animating the most appealing scenes offered in the cartoon. His staggering eye for construction, attention to detail with acting choices, and fearlessness of attacking intricate angles all pay dividends when handling a meticulous, down to earth character such as Sniffles.

Even then, the scenes that demand a higher amount of energy (such as this one, where Sniffles engages in a mad, scrambling, fiery dash through the drugstore) fare incredibly well through their solidity, appealing drawings, and concrete mechanics that render a run cycle snappy and constructed but fluid and loose all the while. McKimson goes so far as to add the detail of Sniffles grabbing his hat and snapping it back into his head after it jars loose from the ferocity of his speed, that little flourish of personality lasting a split second. While the run cycle doesn’t hinge it’s success on that little bit of business, it is undoubtedly enhanced by its addition.

At one point, Sniffles “jumps” between counters and runs on thin air, McKimson’s nonstop run cycle is so hypnotic that the audience doesn’t know the difference.

In fact, the cycle becomes so mesmerizing that even Sniffles falls victim to it, darting straight past a full glass of soda left conveniently on the counter. The pregnant pause on the still of the full soda glass succeeds in adding its own commentary about Sniffles’ missed opportunity. Naughty but Mice does occasionally fall into the vices of its director, but the improvement between this cartoon and shorts like The Night Watchman and Dog Gone Modern is vast. Pauses here are functional and provide their own ironic sort of commentary, rather than self-serving or unconfident. Sniffles running past the glass and then gorging himself after a beat is much more amusing and engaging than a direct trajectory from point A to point B.

Likewise, McKimson and Jones maintain Sniffles’ erratic flow of motion, scrambling a full rotation around the glass before climbing on the side and struggling to drink its contents. Demonstrating the laborious act of Sniffles delicately pouring himself a spoonful of medicine by tipping the bottle to its side and uncorking it allows for a greater juxtaposition to hit here; that same care and gentleness is nowhere to be found in his pursuit for soda, kicking his legs and nearly toppling the glass over. Thick wafts of steam rising after fire meets water further contributes to the hysteria of Sniffles’ mad dash.

Knowing the literal rapid fire momentum has hit its peak, Jones finally allows the effects of the alcohol to hit Sniffles, which it does—hard. McKimson could not have been a better fit for the endearing, appealing and funny facial expressions and kinetic, weighted movement. Sniffles’ drunken weightlessness permeates the screen.

A hearty exhale of steam in tandem with a euphoric “Gee,” seems more akin to the pleasure of a cigarette drag rather than a fire being quenched.

A simple blink paired with the purposefully bloated still of Sniffles’ facial expression speaks volumes. McKimson knew how to manipulate the slightest twitch, the slightest tweak, the slightest blink into comedy gold.

With intoxicated characters come hiccups. Though Sniffles is voiced by the incredibly charismatic Margaret Hill-Talbot, Mel Blanc is perpetrator behind those unmistakable hiccups. Carl Stalling’s muffled, discordant, drunken accompaniment of “You Go to My Head” is a work of art in itself, manipulating it to perfectly suit the action metaphorically and physically; when a hiccup jolts Sniffles off of his feet, the music briefly pauses before moving forward, serving as a literal hiccup in the orchestration.

Whereas cutesy antics of drunken characters stumbling around could be passé and patronizing even by 1939, McKimson’s intricate handiwork and Stalling’s ironic musical commentary do wonders to sustain interest. Leaden footsteps from Sniffles are heartily accentuated by the music score, furthering the drunken, stumbling weight exhibited by the animation.

Likewise with drunken weightlessness. Sniffles gears up a drunken trot to a mad dash in a matter of seconds, his unmoving torso, expression, and flaccid hands a delightfully absurd antithesis to the rapid movement of his legs and the motion lines therein. Similar to the intricacy of the medicine being poured versus the reckless ingestion of the soda, displaying his sober dash to extinguish the flame earlier serves as a wonderful point of comparison to his incredibly controlled run here, exhibiting any and all variations in similar actions that could be milked for comic potential. Repetition is avoided through said variation.

Any sort of humor realized from the discrepancy between Sniffles’ calm demeanor and frenetic energy reaches its peak once he leans nonchalantly against the counter. With his hand in his pocket, the descent remains slow so as to provide ample time for the audience to laugh at the drunken eye contact Sniffles makes with the viewer.

Even then, that doesn’t stop him; an electric razor box does. His momentum takes a few more seconds to screech to a halt, his feet going over his head in the midst of his drunken stupor. The glide of the camera pan is a wonderful addition to furthering the speed, as is the cloud of dust kicked up upon Sniffles’ impact with the counter.

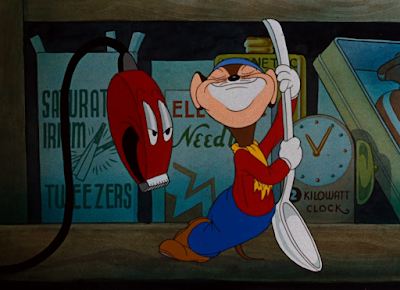

Jones’ Disneyesque roots make themselves more apparent through a friendly, anthropomorphized razor, but the altercation between a pleasantly drunk Sniffles and razor audibly humming responses paired with McKimson’s stellar character acting reduce any sort of patronization. The McKimson animated scenes of Sniffles and the razor are some of the best sequences provided by the cartoon.

“H’lo.” McKimson’s drunken squint on Sniffles is such a small gesture, but one that garners big laughs. Squints would become a defining staple of his own cartoons.

While the razor’s responses are short, they’re surprisingly decipherable through the buzzing, distorted din in which they’re delivered. One can easily understand that the razor has responded “Hello” back—and, indeed, sounds like how a razor would talk if it could talk.

“How are ya?”

Jones delegates the audience’s attention to the razor’s response, providing Sniffles time to rise to his feet without being a distraction. As such, the camera adjusts itself to the right once he’s on his feet, altering the staging to the demands of the scene.

A “Not s’good” serves as Sniffles’ own answer to the razor’s mimicked small talk. “I got a col’ in my head.”

Much like the previous squint, Sniffles analyzing his finger through the lens of his warped depth perception is made riotously funny through the smallest scowl, the smallest pout, the smallest flex of a finger or nod of a head. McKimson was perfectly able to manipulate subtle movements into something just as funny—if not more so—than any wild take displayed in the cartoon yet.

Just as he reassures the razor that it’s “Not s’bad”, a sneeze immediately refutes his claims. The razor leaning forward inquisitively serves as both an intriguing source of character animation and personality, as well as the razor's downfall.

He returns the favor, interrupting Sniffles’ pensive nose wiping. McKimson’s ability to hit intricate angles and knack for solid animation come very much in handy with the demands of an anthropomorphic object, furthering the illusion of life.

“You gotta col’ too, poor fella?” Lifelike head shakes paired with Talbot’s sympathetic, soft spoken albeit slurred deliveries further Sniffles’ endearing appeal.

He answers his own query after a pause. “Yep. That’s whatcha got alright.” At one point, Sniffles briefly displays a McKimson signature hand motion that would continue to pepper his character animation regardless of director; the signature lowered middle finger paired with the extended forefinger and pinky, a gesture that provides a touch of delicacy and intricacy.

McKimson's sharp character animation doesn't falter for a second, subtle acting choices continuing to sustain visual interest and pad out Sniffles' purposefully monotonous rambling. When he tells the razor he'll fix him up and to "jus' wait right here... right here, see, riiiiight heeeere...", Sniffles traces an X on the ground with his finger following another drunken squint of authority. What could be disastrous without a competent animator, voice actress, or director is made a highlight of the cartoon.

Sniffles' inebriated gait proves itself to be amusing through weighted steps and solidity.

His repetitious "stay right here"ing, which has basically turned into a chant at this point, does grow monotonous to the point of being a little grating, but Carl Stalling alleviates that through a call and response orchestration; the final two "stay right here"s are followed by a whining, talking violin mimicking the syllables with 3 mocking slides. A fade to black cements finality to the scene.

Knowing a minute long sequence of Sniffles stumbling to reunite with the medicine would be futile and slightly annoying, Jones instead cuts right to the chase; Sniffles instead returns, armed with the spoonful of medicine, sure to appease both the razor's ailments and the sardonically sorrowful violin score in the background.

Ingesting the remedy, the medicine appears significantly more coagulated, thick, and consequently potent than Sniffles' own dose, highlighting that the razor is not far from joining Sniffles' current state.

A pan left and sedated blinks from the razor towards the audience indicate that a spectacle is approaching, one big enough to warrant the viewer's attention.

Hiccups, a jumpy music sting, and a wide eyed stare further delegate viewing priority to the razor. Like Sniffles, he too excretes tears after a pregnant blink.

Thus spawns the literal explosion, the alcohol serving as fuel for the razor. While the reaction is much longer than Sniffles and some of the bursts of electricity grow floaty, losing their energy, the individual drawings are appealing and distorted enough to convey the effects of the liquor. Likewise, Treg Brown's puffing engine sound effects and the absence of musical accompaniment further the suspense of the inevitable outcome.

Belabored wheezes and coughs from Mel Blanc spawn different forms of electrical bursts, the flashes of light forming entrails rather than shocks of explosion.

Said shocks resume. In the final stretch of convulsions, the movement is caricatured through held frames on twos, the abruptness symbolizing the bouts of shock going through the razor. Had this short been made 3 or 4 years later, Jones' speed would have tripled and rendered the sequence less monotonous, but the only issue present is the pacing; sound design, acting, and drawings are all very solid and amusing.

Paired with the telltale deflation of an engine sound dying, the razor grows flaccid, now sporting his own inebriated grin as he gleefully hums "Oh boy, oh boy, oh boy!"

With cartoon drunkenness comes drunken singing, and "How Dry I Am" was the staple alcoholic anthem of Warner cartoons. Propped uneasily against the now empty spoon, Sniffles engages in a slurred chorus, once again brilliantly animated by Bob McKimson.

Enter the razor, who provides a buzzing round to Sniffles' leading chorus. A drunken duet is then initiated. While McKimson mimics certain acting choices from his previous scenes (whether it be the hilariously drunken squints or hilariously drunken grins), the visuals are kept engaging through differentiation in both Sniffles and the razor; when Sniffles stands tall, the razor bends low. When the razor stands tall, Sniffles bends low. After that, they both unite as one synchronous, inebriated mass, cheek to cheek and forehead to forehead. Solid construction, ability to nail complicated and subtle body angles, as well as incredibly appealing and cute facial expressions render a slow, purposefully obnoxious song number into a spectacle worth combing through for freeze frames.

Sniffles' razor pal promptly passes out after a final bout of harmonization.

"Can't take it, huh?" The good-hearted patronization from Sniffles is endearing rather than pompous, behaving as though he's a seasoned drinker and attempting to fill the big boots he's in. Carl Stalling's arrangement of "Old Pal" is comically sympathetic, but earnest at the same time. He had a magical ability to strike a delicate balance between ironic commentary and genuine heart that few were able to mimic.

"'s too bad, ol' dear fren'..." Condescending head shakes are a must. Stalling's musical saccharinity reaches its peak upon Sniffles' declaration of "Too, too bad..."

Talbot's deliveries and McKimson's handiwork make an exquisite pair, both able to capture just the right amount of humor necessary to make the scene engaging, but also enough to preserve the care and heart necessary for the demands of the cartoon. Too cutesy without a sense of irony is insufferable. Too ironic without a touch of earnest is insulting. A coo of "Poor kid" from Sniffles, who isn't much above from a kid himself, reassures the audience that this is meant to be amusing and not serious. "Sleep tight, ol' pal."

Sniffles gently removing his hat and wadding it to his chest as though he's grieving the loss of his "ol' dear comrade" is almost laugh out loud funny, especially when he puts it back on two seconds later.

Likewise, his drunken, stumbling exit is another thing of beauty. It's a shame that the scene must fade to black as quickly as it does.

Fading up to another animator stresses just how talented McKimson was. Not that the animation of Sniffles stumbling around on the shelves is bad by any means, but one appreciates the level of weight, care, and subtlety poured into McKimson's acting that is scarcely seen by any other animator of this time.

In any case, Sniffles isn't so much the priority as is the pair of yellow eyes blinking in the darkness. Jones' staging is simple yet effective, the boxes of toilet space framing the negative, blank space that then stresses the presence of the stranger.

Revealing the cat's fur to be as black as the shadows is a clever transition on its own, playing with the stereotype of creatures lurking in the dark but also still serving as a threat. With cartoon mice come hungry cats.

Walking at a leisurely pace doesn't bestow the gifts of walking on air that Sniffles possessed previously, which is why a mid-air sneeze (the composition not unlike the gags that would soon become synonymous to Jones' Road Runner cartoons) prompts him to fall into the unseen chasm below, his handkerchief and spinning hat serving as his only remains. His pursuer approaches and peers over the edge.

Pan down to an occupied claw machine, Stalling's drunken motif of "Deep in a Dream" indicating more inebriated antics are soon to follow. Guiding the audience's eyes, Sniffles lazily rolls his head to the left, kicking off a camera pan to focus on the cat jumping down from the counter.

Much like Sniffles' careful analyzation of the words on the medicine bottle, the cat pauses briefly to read the lettering on the claw game, his sentience both a source of humor and immersion.

The same applies as he fishes a nickel from his infinite fur pocket and inserts it into the machine.

Sniffles' condition comes to his aid as he stumbles away from the claw's grip, tripping over the jellybeans littering the machine. McKimson's prior scenes are almost as harmful as they are beautiful, for he sets such a high standard that it proves difficult not to compare to the works of the other animators. The animation is fine all throughout the cartoon, appealing and cute, but one begins to wonder how every scene would look under the care of McKimson.

A scowl and razzing brass score from Stalling illustrate the cat's frustration. Another nickel, another attempt. The protruding tongue and low, hunched over pose indicate serious concentration and devotion.

Having been a pleasant drunk until now, Sniffles grows confrontational only when he steps on a perfume bottle valve, hushing the commotion made by the spray. Electrical droning sounds in the background indicate that the claw is growing nearer.

Indeed it does... only to miss for a second time. Sniffles himself briefly fades as he embraces the bottle, maintaining his slurred shushes. The cat now finds himself in the possession of a perfume bottle rather than mouse. Thankfully, Jones obscures any off screen reaction from the cat, as another shot of him begrudgingly inserting another nickel would grow repetitive.

Only a beat passes before Sniffles regains consciousness, once again growing confrontational as he rises to his feet in search of his departed bottle.

"Where'd it go? Who... who swiped?" In the midst of his aimless stumbling, even the camera halts briefly in its pan, mimicking Sniffles' pace. "I been robbed! P'lice.... p'lice!"

His deadpan cry to the authorities is followed by the camera bellows beneath him springing into the air. Jones continues to have the bellows moving in the next frame, not only to smoothly transition between two separate scenes but to also suggest the height of the bellows. The snarling expression on the cat pressed against the glass informs more about his frustration than any sort of menial cut of him inserting more nickels would.

Double takes = grounded, endearing action. Judging by both the eye take on Sniffles and the shape of the eyes on the cat, Rod Scribner is the perpetrator behind the animation. Sniffles is quick to regain his senses, scrambling off of the bellows with horse clopping sound effects.

Instead of prompting more uneasy stumbling through the machine, Jones makes clever use of his surroundings by allowing Sniffles to swim through the jellybeans, the pan of a camera serving as the only indication of his direction.

That is, at least until he pokes his head out of the beans in time to spot the impending claw. He seeks refuge in the candy once more, grabbing his suspended cap behind him, but is nevertheless a victim to the metallic claw. Interestingly, one held pose of Sniffles ducking for cover holds the trail lines in a stagnant position as well.

Sure enough, he's dropped through the chute and into the clutches of the cat, yet another camera pan obscured through the façade of the machine finding different, more innovative means to execute menial actions.

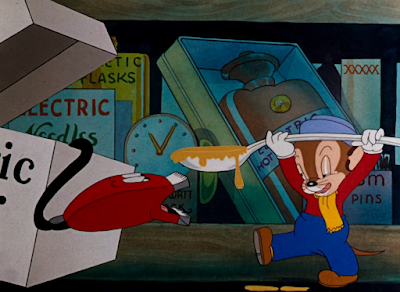

A jump cut back to the razor makes his sudden appearance all the more abrupt, especially as he rouses himself awake with sleepy buzzes. He too shreds his intoxication upon realizing his fellow "ol' dear comrade" is in trouble, marked by a whimsical and snappy eye take.

Ready for action, angry buzzing from both the razor and from the brass section in the music fuel the razor's call to arms. Though the expression is slightly muddled through rapid action and thin lines, the scowl on his face is implied through noises, music, and motion. Brush streaks and zaps of electricity add a necessary busyness that contributes to the freneticism of the razor's movements, doing more favors to boost the animation rather than mask it.

Armed by a triumphant orchestration of "The William Tell Overture", the razor launches into battle. As could be said for most sequences from 1939 reminiscent to this one, the speed necessary to fit the action isn't exactly there, the war era cartoons doing a lot to boost the overall energy and pacing of the shorts, but the urgency is still nevertheless felt through brush streaks, buzzing noises, and dynamic staging compositions, the razor grazing against the foreground in a hurry.

While the gradual build up of suspense between the cat, Sniffles, and razor is held out for a few beats too long, the impact does hit especially hard once the razor rams straight into the cat and propels it off screen, fur flying as it yowls in its flight. A doppler effect on the razor's buzzing as it approaches suspends the tension even more.

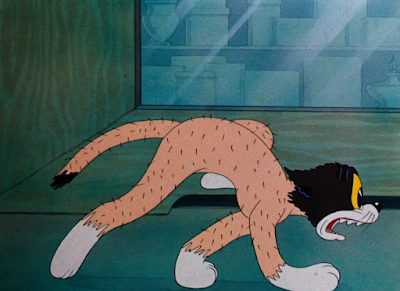

As for the actual showdown itself, the energy of the scene informs the action much more than the drawings themselves, but that is not a detriment by any means, especially in this case. Smears, multiples, energetic brush strokes, frantic yowling, angry buzzing, and triumphant music all clearly indicate that the cat is receiving an unwanted haircut. The loose limbed spasms of the cat nicely bring the motion together and unite it so that the frantic movement isn't a misplaced ball of energy. Eventually, the fight dissolves into a cloud of dust, both to segue onto the reveal of the cat's condition and also indicate the grandiose nature of the struggle.

The razor zips off screen in time to reveal a mostly naked cat cowering in fear. Uneven lines of fur still splotching his skin make the cat seem more pathetic and beat up than a complete loss of fur to begin with. Slowly, the cat begins to uncover himself...

...only for the razor to make a vicious return, the same energy present in the next cycle of aggressive shaves.

While it's certainly difficult to trump the energy and speed present in the brawl between razor and feline, the cat's exit as he runs mostly naked feels jarringly slow and glacial in comparison, lessening the impact of his terrified yowls.

Nevertheless, he seeks a window as a means of escape, only to be confronted by the razor who shows no sign of relenting. Very clear that the razor isn't leaving without a trophy, the cat begrudgingly plucks off a loose tuft of fur from his tail and presents it as a peace offering. He dives out the window, brush trails slightly redundant and not indicative of the cat's speed thanks to the even spacing of the animation.

Cue a page out of Tex Avery's philosophy; the cat returns briefly only to slam the window shut. Another fade to black indicates that all's well that ends well.

Fade back in for one final scene of Sniffles and the razor, their inebriation shed thanks to the scare of the cat. A reprise of both Bob McKimson animation and a jauntier motif of "Old Pal" wrap the cartoon in a satisfying, warm close, a more sober reflection of the antics shown previously. Sniffles' happy, repeated blinks are particularly cute, as is Talbot's deliveries expressing his gratitude.

"It was swe... sweh..."

Living up to his namesake, Sniffles is overcome by an oncoming sneeze. The gentle, confused look from the razor, tilting his head like an inquisitive puppy is a wonderfully endearing and lifelike touch.

The "swell" that Sniffles has been hunting for is delivered in the form of a tremendous sneeze, launching him back up the chute of the claw machine.

Pan left, then up for the reveal, the same pattern that Sniffles took when he was initially united with the cat. We iris out on a suspended but contented Sniffles, pants caught in the claw as the iris draws to a close.

From this cartoon alone, it isn't difficult to see why Sniffles took off particularly well with 1939 audiences or why Jones wanted to use him for as long as he did. While he may be dismissed as a symbol of Jones' slow period today, he certainly oozes an endearing charm not yet found in other Jones stars such as his curious puppies or Tommy from The Night Watchman.

Naughty but Mice may be paced rather slow in comparison to Jones' future works, but, miraculously, Jones was already able to iron out a number of kinks present in his earliest cartoons in just a matter of months. While Mice does have its moments of unwanted glacial timing, much of the slowness is deliberate, especially in the sequences prioritizing drunkenness. Monotony is reduced and kept a keen eye on; this is no longer the era of repeating the same animation of a dog trapped by a dishwasher 3 times in a row. Any sort of repetition (primarily dialogue in this case) is garnered for laughs and not as a crutch.

Bob McKimson's character animation absolutely blows everything else out of the water, to the point where it almost hurts the remainder of the cartoon. His solidity and subtlety and ability to manipulate even the slightest blink or twitch of the finger for the sake of a laugh is a philosophy that Jones would embrace in his later years and soon be hailed for. Likewise, Margaret Hill-Talbot is perfect casting for Sniffles. She captures the ideal soft-spoken, earnest, reserved deliveries present at Sniffles' core, but is also able to remain funny and endearing, especially with his drunken rambling. Jones was a wonderful voice director, if not the best at the studio, and even now he shows great signs of promise.

Sniffles is so full of charisma that his interactions with the razor seem to be more memorable than the climax between him and the cat. Nevertheless, the cat has its own share of memorable moments, though at times serves as the weakest part of the cartoon, the animation sometimes unable to match the energy's demands. Even then, those lapses are very sparse, and the sequence of the razor shaving the cat is carried by energy and energy alone.

Naughty but Mice is easily among one of Jones' best Sniffles entries, rivaled only by Bedtime for Sniffles and Little Brother Rat, and becomes even easier to appreciate when viewed through the lens of a 1939 moviegoer. It certainly deserves a watch for its historical significance alone, but beautiful character animation, innovative musical accompaniment, atmospheric backgrounds, charismatic voice acting and comparatively confident direction certainly serve as worthwhile incentives.

.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment