Release Date: June 3rd, 1939

Series: Looney Tunes

Director: Bob Clampett

Story: Warren Foster

Animation: John Carey

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Porky, Polar Bear, Walrus), Billy Bletcher (I. Killem), The Rhythmettes, The Sportsmen Quartet (Chorus)

After a string of cartoons ranging from mediocre to painfully uninspired, Clampett finally hits yet another bright spot with Polar Pals. With so many of his shorts centered on Porky adjusting and reacting to foreign or unfamiliar surroundings, very few actually take advantage of their environments. Polar Pals is a happy, energetic exception.

Now living in the Antarctic for no reason other than he can, Porky once again finds himself as the unlikely hero having to save his eponymous animal friends from the nefarious fur trapper, I. Killem.

The titles themselves deserve a quick acknowledgement--the name provides Carl Stalling ample opportunity to work his situational music score magic, the titles accompanied by a wintry yet appropriate score of "Old Pal". Likewise, maintaining the snow overlay on top of the "Starring PORKY" slide is a wise and playful choice foreshadowing the wintry environments offered by the cartoon itself.

Like most Clampett cartoons of the era, Polar Pals kicks off with a series of establishing shots, any movement conveyed through a truck-in and dissolve rather than a horizontal pan.

As mentioned previously, Clampett harbored a strong interest in stop motion and puppetry, which he would later leave the animation industry to realize. A morsel of that interest is displayed through a photograph of a globe adorned with fake snow and a “NORTH POLE” sign on top. Much like the spinning globe opening in Frank Tashlin’s You’re an Education, the usage of real life objects not only births a level of creativity that eases monotony and makes an attempt to break formulaic set-ups (though the series of still shots and dissolves here is still very much formulaic), as well as establishing the tone of the cartoon: whimsical, mischievous, maybe even a little naïve.

A “KEEP OFF THE GRASS” sign planted in the ground outside of Porky’s abode-of-the-day solidifies the playful notions hinted by the whimsy inherent in the model globe. Clampett’s set design and ability to manipulate the surroundings established for the cartoon is particularly keen in this entry, making the most of the polar theme.

That too is cemented through the debut of Porky; while he isn’t immediately visible, the snoring and moving bear pelts indicate that the bed is occupied. Though there are plenty of menial details and design choices to ingest—the icy, metallic shine present not only on the walls, but the bed and nightstand as well, the bear pelt blanket, the plethora of icicles coating every possible surface—perhaps the most interesting comes in the form of a photograph on the wall. A closer look reveals a photograph of Petunia Pig (and signed as such), who hasn’t appeared in the theatrical shorts since 1937—Clampett would briefly revive her for two more efforts before she ended her theatrical run. Here, she already sports her Clampett redesign in the photograph, not having been seen yet in the shorts.

Clampett once again goes a little heavy on the truck-in and dissolve transitions, segueing now to a shot of an alarm clock. Borrowing the sensibilities of the early ‘30s cartoons with its anthropomorphic whimsy and wrapping it in the advancements and sophistication presented by animation in the late ‘30s, the clock comes to life only to warm itself. A coonskin hat and mittens on the clock hands that seem like an eccentric decoration choice actually serve a functional purpose.

Though his genius certainly needs to lengthy dissertation nor introduction, Carl Stalling continues to flex his musical magic, the sleepy arrangement of “Deep in a Dream” turning cold, apprehensive, a shiver in the music mimicking the shivers from the alarm clock. One takes for granted the skill he harbored—while the action of the clock coming to life is fun, it certainly would read as much more routine without the playful observance rooted in Stalling’s arrangements.

Discarding its cap, the clock continues to make use of its literal clock hands by grabbing its bell, removing it from its body, and shaking it to rouse Porky. Albeit brief, the scowl flashed by the clock is an amusing way to display its dedication (or, more realistically, its annoyance at the lack of a response) towards its job. Some early use of smears are present in the animation of the bell ringing as well.

It’s not Porky who shuts the alarm clock off, but rather a real live polar bear from the mass of bear pelts. Once more, gags in this vein were hardly new by 1939 standards (such as Freddy’s fur jacket disassembling to reveal itself as a bunch of little kittens in Freddy the Freshman), but the comparative sophistication of 1939 animation standards and ability to convey a broader range of emotion and acting is what truly sells the gag. Instead of happily turning the alarm off and going back to sleep, the bear slams the clock into disrepair with its giant paw before making a sleepy yet contented exit.

The remaining pelts follow suit. Stalling’s ascending, brazen solfège renders a potentially monotonous sequence into something engaging through the synchronization between action and music.

Bobe Cannon is yet again tasked with animating Porky’s introduction, instantly recognizable in the buck teeth, triangular mouth shapes and prominent tongue. He awakens not from the sound—or lack thereof—of the alarm clock, but rather the absence of a pelt keeping him warm. The lone bear cub cuddled up behind him serves both as a gag and a means of Clampett to scratch his itch for cuteness; while he was certainly an advocate for cute animals performing sadistic actions, one gets the idea through sequences such as these that he also loved cute things for the sake of being cute.

As per usual, both Cannon and Clampett excelled at nailing more subtle, grounded acting choices for Porky, such as the sleepy blinks and quick pause as he searches for his lost heating source. Demonstrating him looking in all directions rather than blinking once and shrugging it off allows him to be all the more endearing through subtle acting choices that make him seem more human.

“Hey, eh-uh-ce-eh-come back!”

The addition of the bear cub allows Clampett to tease the censors through homonyms, furthered by the subtle ambiguity of whether he’s pointing to the cub or his rear. “You left a little eh-buh-bee-bear behind!”

A brief moment dedicated to the bear scrambling off the bed once again cements the notion that Clampett enjoyed his cute antics for the sake of cuteness. The same philosophy certainly applies to a number (if not most) of his black and white Porky cartoons.

Continuing to take advantage of the cartoon’s arctic surroundings, Clampett delegates time to show Porky’s regular morning routine adjusted to the zaniness that unfamiliar surroundings birth. Rather than going about his business in total silence, accompanied by only a jolly orchestration from Stalling in the background, Clampett instead defaults to the ol’ reliable bait-n-switch as Porky sings a jovial chorus of “Singin’ in the Batheh-t-tuh-eh-tuhh-eh-Bath-tuh-teh—Shower”.

Perhaps more intriguing than Porky's un-sped singing voice, the novelty of the gags spawned through his speech impediment, or that he is easily able to strut around nude on-screen without flack from the censors thanks to his animalistic roots, is Stalling's musical accompaniment itself. When Porky trips up on his words, the music score briefly comes to a halt, repeating itself when he finally settles on "shower" as a replacement. A miniscule detail subtle enough to easily be missed, but such a fine attention to detail is duly noted and adds a lot.

Then comes the process of showering itself. Bobe Cannon continues to animate the entirety of this scene as well.

While the outcome is inevitable, with icicles forming rather than water droplets, it's executed with so much playfulness and naïve energy that it gets a pass. Stalling's music score is sharp, indicative of every little action; a flighty, vibrating vibe link when the icicles freeze into place, a brassy razzing chord when Porky breaks the shards free. Such is yet another amusing aspect--the shower serves absolutely no functional purpose, purely a vehicle for gags, and both Porky and Clampett accept and revel in the logic rather than question it. Better results are yielded that way.

Polar Pals also cashes in on a trend that would dominate Clampett's Porky cartoons for the next 2 years: the double bounce walk. While it's been used in his shorts before, it would quickly develop into the only way Porky knew how to walk. Exactly as it sounds, a character bounces twice with each step as opposed to a normal, single bounce. The walk was an easy way to convey youth, energy, and innocence--all traits intrinsically tied to Clampett's pig.

Yet another recurring gag Clampett was fond of arrives in the form of Porky drying himself off: a character shaking their rear in tandem with a samba musical orchestration from Stalling. Clampett would reuse the gag in Porky's Last Stand with Daffy drying dishes instead; both instances rely heartily on Carl Stalling's musical genius to work, and both succeed. Rather than interrupting the musical accompaniment at hand with an unrelated snatch of music, Stalling instead remixes his score of "Singin' in the Bathtub" to have an energetic, samba rhythm, horns given a heavy emphasis.

Jovial double bounces resume as Porky struts along his merry way and dives into a nearby parka. Seeing as the audience has toiled enough watching him laboriously dry himself (which is made playful and peppy through the points listed above), Porky instead opts to dive right into his suit rather than segueing into another belabored dressing sequence. Once is fine, and Clampett knew his limits.

Double bounce walk cycles are put aside in favor of more double bounce walk cycles, this time with an added flair: not only are more clothes involved, but more songs as well. Thus introduces the song number portion of the cartoon, a delightfully playful ditty entitled "Let's Rub Noses". While unfortunately soured through a recurring defamatory slur as one of the song's lyrics, the number is otherwise memorable, sweet, and whimsical enough to stand on its own feet.

While it hasn't exactly been established yet, Clampett would from hereon out willfully employ syrupy sweet song numbers in a number of his remaining black and white cartoons. Though the black and white Looney Tunes series itself wasn't under the same musical obligations the Merrie Melodies were (which, at this point in time, a song number was becoming rarer and rarer in those shorts as well), Clampett didn't seem to have many qualms with dropping everything in favor of a song--anything to fill up the 7 minute time slot. His song numbers thankfully are usually rife with energy, with this one in particular one of his best.

Highlights range from both animal antics and Porky having a spotlight to himself: a polar bear bathing with the bath water frozen around his waist, a fish using a whale's teeth like a xylophone as an homage to the cartoons of yesteryear, a penguin popping a walrus' nose like a balloon, and Porky using the reflections of the icy walls as a funhouse mirror. The number is absolutely cutesy--it's initiated through animals all poking their heads out to greet a gaily whistling Porky--but not in a manner that feels shoehorned or condescending. Its energy and mischievous bite make for a very pleasant watch, aided by the dedication felt from Clampett and company. Benefits are also given through having a catchy song number to begin with.

As such, with such a boisterously jovial ambience firmly established, an antithesis in mood is in order. Enter the villain, whose entrance is built up through the ominous cracking of an iceberg and furtive drumroll reflected in the music score. Clampett borrows the entrance from a similar, equally sinister yet playful arrival in his Inj*n Trouble a year prior.

Cross dissolve to a close-up of the killer, explicitly named as such thanks to the "I. KILLEM -- FUR TRAPPER" engraved on the side of his boat. As is typical for the Clampett cartoons, the name is so blunt and on the nose that any corniness derived from the wordplay is pardoned. Any villainous clichés, particularly the furtive glances viewed through a pair of binoculars or the signature Billy Bletcher villain laugh, are fleeting and not mined for serious thrills.

First a dose of sweetness with Porky and his animal companions, a dose of bitterness through the introduction of the villain, Clampett now combines both in what he does best: sweet meets sadistic. One of the greatest gags of the cartoon comes from the point of view of Mr. Killem himself peering through the binoculars. Who slides into frame but three seals happily trucking along their way, Stalling's reprise of "Let's Rub Noses" in the background adding whimsical functionality to their dancing, indicated that the seals are still entranced by the magic of the song number and not randomly dancing on their own whim.

The kicker arrives in a cross dissolve of Killem's point of view as the seals melt into fur coats, said coats still shuffling along to the rhythm all the while. Adding the price tag rubs salt in the wound of the potential animal deaths, and anthropomorphizing the coats continues to make the viewer feel sympathetic but remain engrossed in the transformation.

To bridge the sequence and make for a smoother transition (as well as save a few dollars), Clampett reuses the footage of Killem laughing nefariously. Bletcher puts a more giggly, wheezy spin on his signature villain laugh that in turn freshens up any tired tropes inherent in a '30s cartoon villain.

Back to Porky, who's still engrossed in the magic of the ice turned funhouse mirror. While the distortions aren't riotously amusing by today's standards, props must absolutely be made to the animators in charge of such distortions. Stalling's accompaniment serves as a good buffer.

Even then, Clampett deliberately fakes the audience out by randomly having Porky's reflection resemble that of Edward G. Robinson's, for no reason other than he can. The halt in Stalling's music score allows for a more abrupt transition and, consequently, more laughs.

A number of bygone tropes are revisited in Polar Pals, given a new shine under the current advancements present in 1939 Warner animation standards. First and foremost is the anthropomorphism of alarm clocks, bear pelts, even clothing stands, the second being animals used as musical instruments. Third comes in the tried and true form of an asbestos curtain (better known now as a safety curtain, the irony in the name and materials present duly noted), now given the punny title of "ice-bestos" as Porky takes a modest bow.

Killem supplies his applause in the form of a cannon ball. The elasticity on the cannon itself succinctly mirrors the jaunty pep upheld through the entire short, whereas the footprints in the snow make the backgrounds feel lived in and homely.

Porky's encore is interrupted through a cannon ball reducing the icy curtain to shards, once again a welcome sign of Clampett and co. taking advantage of their surroundings. While Porky's unmoving reflection in the ice is disconcerting, it isn't nearly enough of a visual priority to get up in arms about, especially considering the shards of razor sharp ice obscuring the view. Porky's mindless grin as he gets buried beneath the shrapnel (his cel just disappears entirely rather than going through the lengths of animating him getting crushed) maintains the spirit of the sequence, ensuring it is funny and lighthearted more than painful.

"Lighthearted over painful" is a philosophy he continues to abide by as a large icicle konks a dazed Porky on the head. Rather than bursting into tears as he did with a synonymous gag in Porky in Wackyland, he merely maintains the same stunned expression, which is particularly appealing and cute. The askew parka is a subtle but keen way to indicate that something is amiss.

Cue the signature "blanched with fear" take from one of the seals, the juxtaposition between black and white much more potent in a black and white cartoon and, thusly, all the more amusing. Drybrush trails are visible as the seal struggles to escape from the cannon balls bombarding the scene; it seems that the animators have been embracing the drybrush technique more and more as the year progresses. In an attempt to add depth to the horizontal, flat staging, the seal scrambles out of view and along an icy path that winds towards the horizon, speed successfully conveyed through the path of dust and nothing else.

Much of the energy and success of the climax is owed to Carl Stalling's musical prowess, who once again reprises "Let's Rub Noses" as a spirited yet hurried backing track that connects the entire short together through nods to previous scenes. It certainly energizes a sequence of seals attempting to outrun the cannon; aside from the so-absurd-it's-funny small seal running alongside his cohorts, the scene itself isn't very visually captivating--flat staging and straightforward execution. Nevertheless, the energy is absolutely there, in both the movement and the music, which is arguably a stronger priority than innovative camera tricks in a sequence that thrives off fast momentum.

Shooting the animation all on ones certainly furthers the rush, but the action nevertheless remains clear and coherent. A bigger seal scrambling to jump into a hole in the ice, grab the littlest seal, yank him inside, and cover the top of the hole with a spare chunk of ice lasts only 3 seconds, but every little action is clear in its delivery and motivation.

Clampett delegates any perspective tricks to Porky, who, like the seal scrambling in midair to make an exit, also struggles to capture his momentum. While it could be seen as monotonous to reuse the same sort of delayed take/scramble in air formula so close together, it regains its visual interest and engagement as Porky weaves in and out of the foreground, the musical accompaniment turning a playful, minor key xylophone score as he heads for the hills and takes refuge in his igloo.

Back to Killem, whose violence evolves from the whimsy of cannon balls to sheer gruesomeness of a machine gun. Such is the beauty of Clampett cartoons and his consistent desire to push the envelope; with an end goal of making and selling furs in mind, puncturing the animals with a shower of bullets doesn't exactly seem like the best way to ensure the skins and fur are preserved and not torn to shreds. Violence is the main objective, and playing it off as lighthearted cartoon antics is where Clampett is at his best.

Moreover, the gun violence is stressed as a penguin scrambles to outrun the bullets piercing the icy wall behind him. In this instance, flat staging works to the advantage of the gag: the horizontal staging with the penguin running alongside the wall isn't the result of a lack of ingenuity, but rather a set-up to clearly and concisely display the penguin's wounded shadow reflected on the ice, bullet holes very clear.

Melodramatic death sequences would become a staple in Clampett cartoons, especially if they were made through artifice (The Wise Quacking Duck and A Corny Concerto come to mind.) Replacing the music score with only the forlorn din of a drumroll and piano glissando as the shadow collapses bestows a certain playful yet shocking gravity to the death.

Such is coupled through the penguin's frantic squawking and his shadow encouraging him to march onward.

Seeing as this cartoon has had nudity and gun violence, alcohol is the only logical factor missing from the equation. A drunken walrus contentedly observes as bullets pierce icicles and the walls around him, xylophone glissandos stressing the damage withstood to the icicles as they break apart. Though the walrus' movements are slow, a smear--or, rather, trail of brush strokes--is used to caricature the motion of him turning his head. While these cartoons could still suffer from the glacial pacing standard in the pre-war cartoons, slowly but surely, the directors were learning from each other and adopting new ways to caricature and convey motion and speed.

The walrus almost appearing to raise his glass in celebration of the gunfire is a glorious and blatant disregard for the mayhem unfolding around him. Animated anarchy isn't always in the form of wild takes or brash, unrestrained energy from the characters. That a bar made of ice (complete with the foot rest at the bottom) is just so conveniently at the walrus' disposal makes the set-up infinitely more interesting than just a random drunk walrus drinking in the middle of nowhere. Clampett and company have successfully constructed their own little world in just a matter of minutes, which is why the brutal destruction it faces grows even more shocking.

Signature drunken Mel Blanc hiccups make an appearance once the gunfire subsides. "Ya never even touched me!"

While the gag of the liquid pouring through unseen bullet holes has become synonymous with cartoon slapstick (and even used in live action, whether it be 1941's Hellzapoppin, The Three Stooges, or 1994's The Mask), Clampett employs one of the earliest uses of the gag seen here, if not the earliest use. The lack of a surprised, eye popping take once again cements the beauty of Clampett's world: his characters often embrace and roll with the punches rather than defy them.

A transparent iris wipes to the next sequence of horizontally running animals--this time a pack of penguins. However, they too are quick to slide to a halt, Stalling's music sting and their surprised reactions informing that something unpleasant lurks outside the bounds of the screen.

Said unpleasant surprise arrives in the form of a cannon ball. Both the perspective shot of the cannon ball grazing the foreground and the subtle camera shake make the impact feel much stronger, immersive, and, consequently, more deadly.

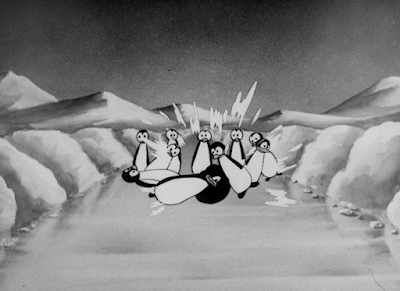

Such a combination works well as the next sequence is a direct antithesis; instead of showing the penguins get blasted into smithereens, the ball is instead transformed into a bowling ball, rolling down a carefully carved ice path turned bowling alley and right into an armada of penguin bowling pins. Treg Brown's sound design is particularly of interest, as when the ball rolls down the alley, the clacks of billiard balls hitting together is heard in addition to the rolling din of the ball.

Likewise, the dead eyed, arguably "off model" penguins once they get bowled over works in their favor, rendering them more inanimate and completing the transformation between animal to bowling pin. Brown's sound design is pivotal to the gag being pulled off well, which is thankfully the case. Yet another absence of music raises the stakes higher than they really are.

Meanwhile, a gang of animals opt to take matters into their own hands, sinister grins plastered on their faces as they too creep into battle bearing arms. That the larger animals are the ones wielding the weapons serves as a keen juxtaposition to the frightened reactions of the smaller mammals; Polar Pals even has its own animal hierarchy.

However, that too is immune from the dangers of Killem's cannon. The sentient blinks of the animals paired with the saccharine string solo of "Home Sweet Home" renders the transformation between animals to den furnishment all the more gruesome.

Just as the audience is led to believe that Porky was taking the coward's way out by hiding, he reappears, armed this time, once again saddling up to the role of the unlikely hero.

Of course, his determined glower is quick to be eradicated as he narrowly avoids a fresh spray of bullets headed his way. Clampett enjoyed casting Porky as the hero to make for a satisfying end, but also giving him the necessary vulnerability to render his heroism in character; a flawless victory would be boring and unfulfilling--a back and forth struggle maintains Porky's naiveté and audience engagement. After all, this is Porky Pig, not Bugs Bunny.

Yet another shot of Killem firing is reciprocated by the Porky, the animation of his rifle lobbing bullets like tobacco reused from Inj*n Trouble. At the very least, Clampett puts a fresh spin on it by having the bullets carve out the shape of a mallet in a snowdrift, which bonks Killem on the head thanks to a bullet severing the handle. Treg Brown's "puit!" spitting and bell ringing sound effects paired with Stalling's energetic music elevate the playful antics present.

On the topic of reused animation, the blow withstood by Killem to the head is executed in a very similar manner to Porky's own dazed walkabout in Porky's Naughty Nephew. Killem here has the added benefit of drybrush streaks added on top, aiding to blur the movement together and make the vibrations read as all the more disorienting and organic.

Another quick cut is made back to Porky, the closer angle masking the reuse of the previous scene. Though the cut mainly serves as a bridge to display the next abuse withstood by Killem, it also provides a rapid back and forth ping pong of energy between Porky and Killem to maintain the momentum demanded by the sequence. While nowhere near the level of artistic manipulation that Frank Tashlin was able to execute similar cuts in, it certainly does its job here just fine.

More reuse (here more a recycling of gags rather than traced footage) from Inj*n Trouble is delivered through Killem doing a scramble take out of his pants. Thus features a trait Clampett would use for years to come; when wanting to emphasize particularly wild takes or big bursts of energy, he would have his characters go off-screen, as though even the bounds of the screen can't contain their fervor. It would grow to be much more potent and noticeable as the years went on, but a start is a start.

Killem then gets a dose of his own medicine, with bullets pinging him in the rear as he runs. Mel Blanc provides his screech of "YYYYYYYYEOW!!" rather than Billy Bletcher.More attempts to get innovative with the staging composition are realized with Porky firing his rifle in the foreground and Killem running into the horizon. Diagonal staging such as what is displayed here conveys a natural, organic feeling of movement.

Rather than aiming at Killem himself, Porky opts to shoot his ship down instead, giving him no means of escape which seems oddly cruel in itself.

Clinging to Polar's overarching motif of reprising bygone tropes under the advancements of the current technological achievements, Killem's boat becomes anthropomorphic and sentient as it holds its "nose" while sinking into the icy waters. Gloved hands and rubber hose limbs further the anachronism, but certainly doesn't detract from it.

Thankfully for Killem, a kayak (complete with a paddle lying in the snow) provides easy escape, docked at the bank of the snow for maximum accessibility.

Porky's take as he realizes Killem got away is one of the most appealing bits of animation the entire short has to offer. Details such as the slightly lidded eyes aim to convey a more mournful, glum expression that conveys more sentimentality and innocence over a stock "slightly knit eyebrows and frown" expression, and the ears protruding from his hood add more appeal than the comparatively "bald" look when the ears are concealed.

Not only that, but the animation itself moves wonderfully. Porky's halt is caricatured through a snappy, elastic take, making his "landing" feel all the more kinetic, and the rifle floating a second longer in the air provides a solid discrepancy between the physics of Porky and the gun. While the gun landing in the snow suffers from being too stiff thanks to the lack of an overshoot and settle, the audience is intended to have their eyes on Porky, not the gun.

All throughout the altercation between Killem and Porky, Stalling's arrangement of "Let's Rub Noses" transforms from an innocent, almost childish major key to a sinister, mischievous minor key depending on who is on screen. It serves as a wonderful way to establish the good vs. evil, kind vs. mean motif while establishing a connection that is coherent and clear.

Killem settles the dispute in a calm, professional, dignified manner: a mocking waggle of the tongue and a signature Billy Bletcher laugh. Rather than be disappointed at his lack of captured game, he thrives in Porky's unsuccessful attempts to get rid of him.

Thankfully, the animal antics established through the earlier song number serve a purpose. Killem is quick to discover that his mode of transportation isn't a kayak, but an angry whale seeking vengeance. While the water effects on the whale teeter on the crude side, flashing and remaining stagnant rather than actually dripping off the whale realistically, the visible brush strokes of the paint to give it a more foamy appearance is much more interesting than opaque white blobs of paint.

In spite of the repeated back and forth between Killem and Porky, the resolution of the whale blowing Killem into the horizon via blowhole almost comes as too abrupt, mainly because we never see the impact of Killem's landing. A splash or even just a metallic "TWONNNNNNG!" sound effect from Treg Brown would ease the flow of his exit. Nevertheless, it's very clear that good has presided over evil.

As such, Clampett treats the viewer to another dose of self indulgent cuteness as Porky celebrates in the company of his cuddly companions. Yet again, Stalling's reprise of "Let's Rub Noses" serves as a wonderful way to wrap up and connect the entire cartoon back together, its innocent and spirited woodblock arrangement mimicking Porky's own childish dance and joyous exclamations of "Oh ih-buh-be-eh-boy! Oh, eh-weh-weh-weh-whoopee! Heh--"

Clampett's comedic timing is incredibly sharp as Porky's gallivanting sends him plummeting into the icy waters with absolutely no warning. No signs of a fracture forming, no rumble of the ice, no sort of build-up that would spoil the surprise or lessen the impact. The only potential sign of any sort of foreshadowing is that they went through the liberty of including the sounds of Porky's boots hitting the ice--it's incredibly subtle, but definitely there.

An open mouthed smile is infinitely a much warmer alternative than any sort of befuddled blinks. All's well that ends well.

While Polar Pals occasionally dips into some of the less desirable Clampettisms, it is easily one of the best cartoons offered by the Clampett unit in quite some time, largely in part to its energy and coherence. As some historians have noted, Clampett often excelled in tending to the details rather than looking at the bigger picture of his films. For example, at its core, Draftee Daffy spends the majority of its runtime having Daffy screaming hysterically as he runs around his house. While that in itself sounds like an awful premise, it is saved largely through Mel Blanc's expert voice acting, Carl Stalling's fervent musical accompaniment, and the versatility of Clampett's Daffy as a whole, whose broad, often irrational mood swings create a large variety of different comedic avenues to be explored. The story itself is weak, but it thankfully doesn't rely on the story to be successful.

Polar Pals is a rare case of Clampett tying his story together. Stalling's recurring musical motif of "Let's Rub Noses" plays a vast part in this--it serves not only as a callback and reprise to the main musical number, but establishes themes for the characters: Porky is represented through the peppy major key orchestrations. Killem is represented through the mischievous minor key orchestrations. Not only that, but serving as a musical accompaniment when the animals retaliate and celebrate themselves reminds the audience of the equally jovial antics shown during the song number. It serves as a satisfying and consistent means of bridging all of the separate acts and gags together as one.

As mentioned previously, one of Polar's biggest selling points is its boundless energy. While the distortions, takes, and movement pale in comparison to Clampett at his most overzealous, everyone appears to have a pep in their step. Porky's double bounce is an easy identifier, but even the manner in which the animals dance, run, flail their arms, defend themselves, get blown up, etc. all contain a particularly potent snap and edge to them that keeps the audience wanting more, even if some of the gags themselves aren't the most thrilling. It's the execution that matters most, and Clampett's execution throughout much of the cartoon is spot on.

Certain pitfalls such as reused animation (which, as has been harped on previously, is much easier to critique today with the immediacy of these cartoons at our disposal) or gags, as well as arguably uninspired staging or repetition through back and forth fighting sequences do at times hinder the cartoon from its maximum potential, but thankfully don't serve as an active detriment. While Porky may not have many lines to himself, he doesn't nearly feel as honed in as he does in cartoons such as Chicken Jitters or Porky's Movie Mystery. Clampett provides ample time for him to endear himself through the beginning, and certain mannerisms (namely dancing on top of or reflected in the ice, even the brief glimpse of disappointment as he realizes Killem's gotten away) continue to keep him quirky or engaging in the midst of the surrounding action.

Polar Pals seems to often be cited as a cartoon people remember from their childhood, and for good reason. It may not be Clampett's best, but it absolutely comes as a relief in the midst of largely uninspired and mediocre entries from him in the 1939 year so far. While it has a shorter runtime at about 6 and a half minutes (including opening and ending titles), a longer runtime likely would have hindered it and made the action feel more monotonous or the padding more noticeable. Though it hasn't aged flawlessly on account of the Inuit slur in the song lyrics, it is absolutely an outing worth scoping out. Shamelessly energetic, playful, sharpened by Clampett's sense of humor, it is a very fun and enjoyable way to spend the next 6 minutes and change.

Link! The cartoon is also available on HBO Max.

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment