Release Date: April 22nd, 1939

Series: Looney Tunes

Director: Ben Hardaway, Cal Dalton

Story: Tubby Millar

Animation: Herman Cohen

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Porky, Porky's Father, Jockey, Assistant, Judge), Joe Twerp (Commentator, Auctioneer), Pinto Colvig (Teabiscuit, Engine, Old Man, Horses)

It’s back to the pig with Hardaway and Dalton, this time starring once again as a farmer (or the son of, rather) in Porky and Teabiscuit. Borrowing inspiration from cartoons such as Milk and Money and Porky the Rainmaker, Porky accidentally buys an $11 racehorse at an auction with the money he was supposed to give to his father. As it turns out, a steeple chase touts a convenient $11 prize; unfortunately for Porky, his Teabiscuit is certainly no Seabiscuit.

Hardaway’s hayseed heaven is swiftly established not even seconds into the cartoon. An iris in reveals a sign advertising “Phineas Pig & Son — Dealers in HAY & GRAIN — and all that sort of things’n stuff”, Carl Stalling‘s cornpone accompaniment of "Rural Rhythm" indicating that Podunk gags are upon us.

Pan down to reveal the Phineas Pig in question, a man looking more akin to Porky’s grandfather rather than father as he hauls a bag of feed into a truck. As previously mentioned, Porky and Teabiscuit borrows a number of story beats from cartoons of years past, two of them being Porky the Rainmaker and Milk and Money. Porky’s father (then voiced by an unsped Joe Dougherty) stars in both.

As he did in Porky’s Poppa, Mel Blanc provides the vocals for Porky’s father here. The aforementioned cartoon had the distinction of adequate voice direction; this one does not, and Blanc’s stuttering of “Now where’s that guh-gih-guh-eh-guh-gih-good for nothing boy of mine?” is excruciatingly wooden.

The same applies for Phineas’ attempts to wrangle his son through mechanical shouts of “Porky! Buh-bih-bih-buh-eh-buh-beh-Porky!” Blanc’s deliveries for Porky in the H/D efforts suffer enough as is, but at least they have the benefit of being sped up and some semblance of the character’s personality in mind—no such luck here.

In addition to Teabiscuit’s Frankensteining of cartoon stories (which will grow more prominent as the cartoon progresses), Hardaway and Dalton seek inspiration from themselves—that is, from Dalton. Similar to Porky’s Phoney Express, Porky is cast yet again as a child, and one who is a fanatic about horses. Here, he slaps the hide of his equally dinky partner in crime, both unified by their large pie eyes-o’-youth.

“C’mon, eh-chuh-chee-chee-eh-Cheesecake! C’mon, cheh-chee-chee-ehh-cheh-chee-eh-Cheesecake!” Even in the briefest of spurts, the dialogue is extraneous and repetitive; out of the 5 lines spoken in the cartoon so far, 4 of them have been repeated in their respective pairs.

Trucking out reveals a stronger Phoney Express influence in that Porky only pretends to ride a horse; here, said horse is a toy bicycle. Dalton and Howard’s approach of the gag at least didn’t hinge any and all laughter purely on the reveal—while Phoney Express has its vast share of issues, Porky riding a broom and deriving the humor from his innocence/obliviousness to getting yelled at is not one of them. Here, the joke hinges solely on the gag reveal alone, which isn’t very funny to begin with.

Nevertheless, Porky’s pretending is cut to an abrupt halt in the form of a rock. Tripping over the obstacle, Porky mechanically flops to the ground and rolls to a convenient stop by the storefront. Interestingly, a portion of the background remains unpainted; the detailing on the wooden porch stops right before the doorway, melting into an inky gray void.

Ever caring and gentle, Pa chastises Porky by telling him to cut the horseplay and take the load of feed over to the racetrack. Porky merely listens in vacant obedience.

That is until he catches wind about the racetrack part. “Racetrack?”

Cue more similarities to Phoney Express, in that Porky is jubilated to indulge in his passions. The Porky in Phoney Express was much easier to sympathize with (and even then, given the circumstances, that’s not saying very much); his childish jubilation was believable, if not a little annoying. Here, Blanc’s delivery of “Hot duh-dee-dee-diggedy-duh-de-do-duh-deh-daw-duh-deh—oh boy,” is funny, but severely underplayed and somewhat lifeless as a result.

Porky darting offscreen provides Hardaway an excuse to tack on more extraneous dialogue, monotony growing due to the unceremoniously flat staging whose obligation to fit two characters has since passed. Porky’s father tells him to collect $11 exactly.

“And don’t you duh-dih-dih-dare lose none of it, neether! I-I mean, nuh-neh-nih-neither!” One can imagine Hardaway patting himself on the back for that job (not) well done.

At the very least, the story behind the next sequence is more interesting than the scene itself. Porky, whose mannerisms seem to evoke that of a small child’s but is apparently trusted enough to drive a truck, struggles to get the engine running, the car briefly deflating beneath itself before trucking to a start. The struggling whirrs of the engine are provided by Pinto Colvig, who, evidently, made the sounds by blowing into the opposite end of a trombone, performing the bit on a handful of Jack Benny radio shows in 1937.

While that would be plenty in itself, any and all car gags are further exhausted as Porky hits a ditch, swerving around strategically placed haystacks in an attempt to boast combined perspective animation and a gag of the feed flying into the air.

Feed bags rain back down into the back of the truck, but only when Porky gets back on the road, heading on his merry way. Having him drive straight forward rather than obey to the curve in the road reads more as an easy cheat rather than a display of his carelessness.

Warren and Dubin's “Jeepers Creepers” makes its Carl Stalling debut, a jaunty accompaniment to Porky peeling into the racetrack. With the aid of some unattractive animation work, he hauls the feed into the nearby stables by sliding the bed of the truck out like a drawer. One desperately longs for (and questions) the success exhibited in Bars and Stripes Forever.

In any case, Porky and Teabiscuit does have its meager share of appealing and intriguing animation. Porky happily emerges counting a wad of bills, his design incredibly streamlined, flat, and stylized compared to the general presiding mushiness. The simple, geometric shapes and simplicity in the detail—or lack thereof—suggest the work of perhaps a former Frank Tashlin animator (Volney White?) Nevertheless, no matter who animated it, it serves as a welcome breath of fresh air.

The same applies to the excited take he does when something catches his eye offscreen.

Porky the Rainmaker (and to a similar degree, Porky’s Garden, which is also reminiscent to the aforementioned cartoon) serves as the next piece of inspiration, here in the form of Porky getting distracted by a snake oil salesman.

Snake oil auctioneer is more like it. Voiced by someone who is surprisingly not Mel Blanc, the sneering auctioneer offers a rope for sale in all of its exciting glory. Gil Turner is responsible for the animation, identifiable by the highlights in the eyes, prominent teeth, extraneous head tilts, and slow yet constant movement.Conflict arrives in the form of an old man who’s hard of hearing. Per his asking, Porky is kind enough to tell the fella that the time is currently 11 o’clock.

Unfortunately for him, the auctioneer hears Porky and mistakes it as a bid. “Do I hear $11?”

“Ya say, ehhh… 7 o’clock?”

It seems like an odd choice that the conflict is derived not from Porky’s own stuttering (which could present a multitude of comic misunderstandings on its own) but instead a hard of hearing elder. Perhaps the scenario would be more funny if it were executed as such; the staging and deliveries are relatively flat and straightforward. Nevertheless, Porky’s insistence of “Nuh-nih-no, eleven!” is enough to bag him the bid overheard by the auctioneer.

“SOLD! To the lad with the checkered teeth!” Miraculously, a somewhat clever line of dialogue is present in a Hardaway and Dalton cartoon.

Little time is wasted as the auctioneer plucks the $11 out of Porky’s overalls, trading it for a rope. Poor vocal direction for Blanc make Porky’s rebuttal of “But I duh-dih-dih-dih-didn’t buy this rope!” sound like a minor inconvenience at best.

Nevertheless, the auctioneer clues Porky in on the goods; the real prize is what’s attached to the end.

At the very least, H/D do an adequate job of preserving any semblance of surprise; rather than panning right to the object of Porky’s money, we instead follow him as he cautiously follows the rope, the staging and mannerisms appearing to be heavily inspired from a scene in Porky’s Garden where he uses a vine to track down a pumpkin.

His prize here, however, is no pumpkin. Whinnies provided by Pinto Colvig, Porky bumps into his new purchase. His awed declaration of “Oh eh-buh-bih-bih-beh-boy! A racehorse!” appears to be the only line of dialogue so far that has any sort of believable passion and emotion behind it. “Ride, Tenderfoot, Ride” proves appropriate cozy accompaniment.

The staging of a jockey coming to retrieve his horse works well; while it suffers from terminal H/D bloating, the delivery and composition is simple and swift enough to clue both Porky and the audience in that this isn’t the real prize. Porky physically having to be pushed back to accommodate for the jockey’s movements, still patting the horse, adds the slightest bit of attachment between pig and horse—the pathos there is much stronger than any interruption provided by a surprised take before the jockey enters.

If the tapered eye designs and wrinkles on the jockey weren’t indicative of Rod Scribner’s drawing style, the wild, stylized, wrinkly take Porky does as he spots his true prize offscreen are.

Pan left to one $11 horse. For once, the limitations and lack of appeal present in the character designs of Hardaway and Dalton cartoons work in their favor—the horse looks much more broken down, decrepit, and ugly as a result. Scribner’s fetish for wrinkles strengthens the wheezing, laborious coughs heaved by the horse. Meet Teabiscuit.

Stalling’s wah-wah accompaniment of “The Old Gray Mare” adds a fitting, ironic commentary to Porky’s justified reaction of disdain. Once again tapping into the roots left by Porky the Rainmaker, particularly in the realm of “salesman dismisses Porky by telling him not to bother him”, any attempts to bargain with the auctioneer climbing into his car is curtly dismissed. “Get away bud, don’t bother me.”

Porky is thusly consumed in a cloud of dust as the scam artist peels out of the lot. While not lightning fast, the speed of the auctioneer making his leave fares comparatively well.

“Eleven duh-dih-duh-de-dollars for an old, eh-buh-be-behh-buh-be-broken down racehorse…” More attempts at pathos are strained by flat vocal direction and unappealing Gil Turner animation as Porky sulks to himself. “Ohh… eh-beh-eh-jee-just wait ‘til Pop hears about eh-thuh-the-thu-the-this!”

Never one for subtlety, Hardaway and Dalton make the Seabiscuit/Teabiscuit pun as obvious as they possibly can. If the title of the cartoon wasn’t any indication, then hopefully the unsubtle horse blanket fills in any missing blanks.

Not in the mood for any cuddles right now.

With ‘30s horse racing cartoons come racist depictions of horse handlers, with Porky and Teabiscuit proving no exception. Blanc’s deliveries are as rancid as every other Stepin Fetchitesque caricature voiced by him as the handler tells Porky to get ready for the steeplechase.

“See-eh-see-eh-seh-steeplechase?”

Steeplechase. Tex Avery’s Milk and Money influence grows significantly stronger in the second half of this cartoon, in which Porky also mistakenly enters a horse race. The sign gag here borrows obvious cues from the likes of Tex Avery and Frank Tashlin.

Porky’s jubilation is conveyed through a failed attempt at a quick, Tashlinesque exit, with Porky and Teabiscuit disappearing to the stables into a cloud of smoke. While the departure is fast enough for H/D standards, the lack of hook-up poses in the next scene, with Porky and Teabiscuit already standing firmly in place, disrupts the flow and softens the impact of any speed.

“Eh-nuh-ne-now, you stay here weh-wee-we-weh-we-while I get dressed.” An easy identifier of Gil Turner’s work seems to be the buck teeth he gives Porky; not unlike Bobe Cannon over in Bob Clampett’s unit.

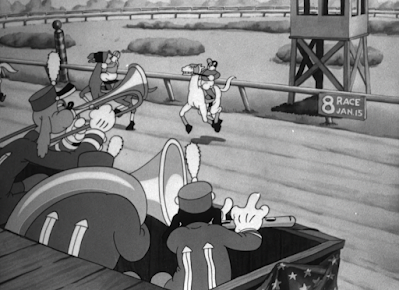

A departure from Porky allows opportunity for more Hardawayisms. A wide shot of the racetrack and the crowded stands dissolves to a man preparing the signal for the race. In pure Hardaway fashion, his entrance is conveyed through a stand opening like a drawbridge. He prepares his bugle…

…and, in a mildly amusing Hardawayism, places the needle on top of the spinning record donning his trumpet. After all, it is the modern year of 1939. The gag is corny, but politely so—it likely would have been aided by having the bugler stand away from the horn, keeping the trumpet away from his lips to further stress the importance of the record. Here, placing his lips on the mouthpiece just makes it look like he’s blowing into the horn that conveniently has a record on top with very little movement.

Nevertheless, it’s enough to entice Teabiscuit, who willfully deserts his post in accordance to a drum march cadence reflecting his call to duty. As is standard, the music conveys more about the personality than the animation does.

It is then that we cut to a somewhat bloated scene of Teabiscuit gallivanting around on the track, taking eager note of the trombone sliding from the band.

A close-up by the likes of Herman Cohen (noticeable in the general solidity of the animation, thick eyebrows, and prominent pie cuts in the eyes as opposed to highlights) asserts the horse’s infatuation with the horn, all too happy to eye down the moving slide. While not exactly thrilling, the emphasis on the trombone playing reflected in the music is a welcome immersion.

Furthermore, the next shot of a nearby kid blowing up a balloon, popping it, and causing Teabiscuit to head for the hills in a blind panic fares well from comparatively appealing animation and designs. Exaggeration on Teabiscuit and prominent wrinkles on the tuba player when he blows suggests the work of Scribner, supported by the tall eyes on the child. Drawing style presides more so over than the animation mechanics itself, but any victory is a victory in a H/D cartoon, no matter how small.

Back to Gil Turner’s handiwork as Porky enters the stage in a jockey uniform; while normally I’m lenient to certain applications of cartoon logic, it does certainly beg the question how Porky was able to snag a uniform just in his size if he entered this race unwillingly, knowing where to find said outfit at his disposal. It’s a small inconsistency, but an inconsistency nevertheless. Milk and Money at the very least still had Porky race in his milkman’s uniform.

Looking for his missing steed, Porky finds his racehorse cowering in a nearby bed of hay. Lone pieces of straw are strewn about Teabiscuit’s head, though the gag is muddied through the similarity in value between the background and the cel paint color for the straw.

Rather than a “There you are!” or a “Where have your been?”, or even a "Come out from the-thee-eh-the-the-eh-thehh-beh-eh--aww, ceh-quit your hidin'", Porky instead wordlessly pulls Teabiscuit out from the muzzle, yanking him by the cheeks.

A cut is then made to the start of the race, the starter using the same prototype Marvin the Martian voice used by the jockey escorting Porky’s thought-to-be racehorse. Props to Hardaway and Dalton for clearly diving the staging between starter and contestants; the starting booth and billboard advertising the race’s odds frame the racers and subconsciously direct the viewer’s eye towards them.

Right on cue, the racers take off per the explosion of a gun in the air. That is, all except one.

Recycling a gag from Porky’s Phoney Express, a jockey kicks his horse into gear, who is propped up at the starting line with a kickstand. Engine reviving sound effects and the eventual speed in which the horse takes off soften the blow, but the gag grows to feel unnecessary, especially considering it’s three times as long as the same gag in the aforementioned cartoon. As mentioned in previous Hardaway and Dalton reviews, a number of certain issues such as these seems to be traced more so to Ben Hardaway rather than Cal Dalton.

On the topic of Hardawayisms, indulgence to appease his humor is made in the form of one Joe Twerp, providing the voice of the race commentator whose spoonerisms are in full display. Thankfully, the pauses are less laborious than his deliveries in Gold Rush Daze, though the push to stress his spooneristic speech feels more excessive here.

“They’re off! Yessir, they’re off in a doud of clust. Er, clud a roud. Er, bust a crust. Anyway—aww, there they GOOOOO!”

Animated by Rod Scribner (indicated by the tall eyes sported by Porky), the sequence of him ushering Teabiscuit to the track and asking a crowd of spectators “We-wee-weh-weh-wee-which way'd they go?” suffers from slow, mechanical movement from the crowd. Porky’s query is answered in a slow, stiff jerk of the thumb in unison, any sort of humor to be found in such a response squandered by the slow delivery.

Nevertheless, Porky’s exit remains swift in Scribner fashion, Teabiscuit’s animated distortions unhindered by the distance of the shot. Designs in the crowd are varied—perhaps not appealing, but the differentiation between the spectators and certain design choices (one man has dot eyes, another woman sports a rather fancy hat, one man has a monocle and mustache, a hippo and dog faced horned creature also dotting the congregation) make for a much more engaging result.

Attempts at speed gags are made, an obvious endeavor to mimic the timing and gag sense of directors such as Tex Avery and Frank Tashlin. Perhaps the action of Teabiscuit taking off past a line of bearded spectators is fast itself, but the timing suffers, a cloud of dust and shot of the tied up spectators lingering too long to maintain any sort of impact. The symmetry in the composition here reads more as artificial and disconcerting rather than clever, united; having their beards all be in one, singular tangle would have been much more amusing and less cold visually.

Cutting to a wide shot of Porky in the track reveals he’s been misguided. That is, the remainder of the racers zip past him in the opposite direction, prompting a sluggish turnaround, belabored reaction take and all.

Likewise for Porky and Teabiscuit cutting through the grass and hopping back into the track. The gag doesn’t land nearly as well—if at all—without the accompanying speed and pacing it demands, which this sequence certainly does not have. Teabiscuit runs at a leisurely gallop at best, a stark incongruity to Stalling’s sporty musical accompaniment.

Jack King, of all directors, appears to be the source of inspiration for the next gag—if not him, very much the time period he directed in. A straightforward shot reveals a jockey’s horse stretching its body out diagonally in an attempt to block Porky from either way. Sluggish pacing aside softening the blow, the staging feels similar to a scene in King’s The Fire Alarm, which, even then, felt more energetic than what is the case here. An attempt to be creative with the moving background perspective instead reads as crude, slow, and retrograde. Very strong early-mid ‘30s atmosphere, and not in a way that is helpful.

Similar critiques apply to the next scene of Teabiscuit biting the jockey’s horse on the ass, using the horse’s take in the air as an excuse to dart below and pass by. The motion of the animation suffers primarily; Porky’s speeding up is a matter of strategic placing of cels, not actually reflected in the dynamics of the drawings themselves, and reads as incredibly mechanic as a result. Likewise for the jockey in the air, who speeds back into place by merely putting the cel back to where it was. An abrupt gap in the momentum results as the consequence.

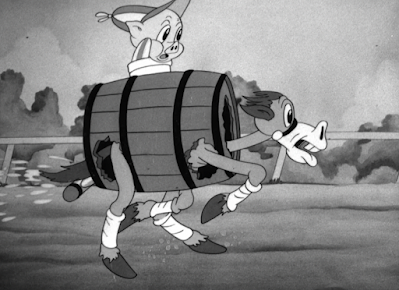

At the very least, Gil Turner’s animation of Porky and Teabiscuit sliding in a mud slick (that just so happens to be the result of a random person driving a leaking barrel truck on the track in the middle of the race) fares better in terms of organic movement, the drawings looser and less stiff, the even, glacial timing somewhat fitting accompaniment to the gliding slick of the mud.

And slide they do, right into the truck. Thankfully, the explosion and cloud of dust that follow aren’t held out any longer than they need to be. With the dust parting, the reveal is presented, the barrel snug around Teabiscuit as he continues to run.

Porky’s head popping out of the top after a brief pause adds a little more organic timing to the sequence.

With a jockey approaching from behind (whose approach is marked only by a cut to him and his horse running, not any sort of interaction or indicating of speeding up reflected in the animation), Teabiscuit is prompted to squeeze out of the barrel in a flurry.

Said barrel is left spinning in the air and bouncing on the ground to accompany its new mate.

Belabored, befuddled blinks to the audience are a must in a Hardaway and Dalton cartoon.

More spoonerisms ensure as we resume to the commentator. After tripping over his words, pauses too evenly spaced out to sound like a natural struggle, he voices the thoughts of viewers everywhere with a concession: “Aww, who cares?”

Rod Scribner animates a particularly appealing (and wrinkly) shot of Teabiscuit skidding to a halt on the track, galloping back to the bandstand to observe the trombone sliding back and forth. Porky, however, is not pleased. The motion falters slightly in its execution (it almost looks as though Porky is directing Teabiscuit towards the trombone rather than a forceful takeover), the drawings themselves are appealing, tall eyes on Porky and a slightly tapered head shape giving him more organic life. Likewise with Teabiscuit.

Herman Cohen resumes the closeup of Porky struggling to get Teabiscuit to go, trombone blares in full force as the horse observes diligently.

After a brief shot of the jockeys racing along the track with some comparatively nice perspective animation, Hardaway and Dalton get creative with the staging. Focusing on the kid from earlier, hearty breaths into his balloon prompt it to fly out of his grip. The camera following the balloon into the air, albeit brief, is a relatively artsy move for the likes of H/D, an attempt to immerse the audience in the action (even if it is just a simple pan up and down.)

From pan to truck-in, the camera cuts to the balloon flying into the tuba of one of the bandstand members. Like the trombone, audibly highlighting the notes of the tuba as the player inevitably inflates the balloon is a welcomed, playful touch.

Back to Porky, who is now on the ground. Uninspired, repetitious writing resumes as Porky eloquently begs “C’mon, eh-tih-eh-tih-eh-tih-eh-teh-teh-Teabiscuit! Eh-cuh-cih-cih-ehh-ceh-cee-ehhh-come on!” One gets the impression that Hardaway and Dalton believed that Porky’s stuttering served as an adequate substitute to any sort of writing or dialogue with actual substance.

More attempts to be artsy are conveyed through a somewhat Tashlinesque upshot of the horses running on the track, essentially trampling the camera in the progress. While the shots are engaging, the short bursts in which they’re displayed feels more like a brief excuse to display of the staging rather than convey any sort of urgency at the race winding up.

On the topic of urgency, the balloon from the tuba bursts against Teabiscuit’s rear, sending him and Porky in a tailspin. Milk and Money’s influence becomes much more concentrated here; in the aforementioned cartoon, a horsefly zings Porky’s horse that sends the horse in its own tailspin, zipping laps around the track and coming in first.

3 years later, Tex Avery’s version of the gag was much faster, simpler, and bolder than Hardaway and Dalton’s adaptation. Still, the speed is certainly fast enough for their standards. That Teabiscuit and Porky dissolve into a blurred streak at all is a miracle in itself.

“The winnah!” The race starter from earlier also just so happens to be the judge. “Teabiscuit!”

Thankfully, the snappiness of Teabiscuit skidding back into place by the starting line, a befuddled Porky on top as a flower wreath is tossed upon the horse’s neck and a swarm of photographers crowd into the scene fares well. Like everything, it could fare better through a little more abruptness (one wonders how Frank Tashlin especially would have maneuvered the scene, always one for caricaturing his motion), but works well enough as is.

Unfortunately for Teabiscuit (and Porky), the flash bang of the photographer’s camera prompts him to explode again and take off in a whinnying blur.

Said explosion is a propulsion to the next piece of business. Rather than running more laps around the track or running OFF the track, irising out on a Porky and his out of control horse crashing through fences and speeding into the horizon, the scene cuts as anticlimactically and as jarringly as possible to the bandstand. No Porky in sight, no speeding horse in sight, no semblance of any sort of connection between the two scenes in sight.

Teabiscuit’s “wah-wah-wah waaaaahhhhhhhhh” trombone solo feels like rubbing salt in the wound.

At the very least, an iris out on a wheezing, coughing horse, convulsions and contortions provided by one Rodrick Scribner, isn’t a total loss.

After viewing Porky and Teabiscuit, one now questions the success of a cartoon like Bars and Stripes Forever twice as much. Bars is not a perfect or even great cartoon, but Teabiscuit is abysmal compared to it; filled to the brim with every single bad Hardaway/Dalton habit. Empty, repetitive, unnecessary dialogue, pregnant pauses, belabored gag deliveries, unfunny gags to begin with, unappealing animation, and a total lack of coherence and cohesion to begin with.

As expressed in previous reviews, Hardaway and Dalton often seek out previous films made by their cohorts for inspiration. That isn’t a problem in itself, but more so the execution; the cribbing is surface level at best, with anything that made the source material funny or successful to begin with lost in translation, with very few twists on top to bestow it any sort of identity.

Milk and Money may be bogged down with pre-Mel Blanc era voice acting and the relatively primitive mid-‘30s drawing style, but, even for a cartoon made in 1936, is three times as fast, three times as coherent, and three times as funny. The stakes are high and the plot in that is simple: Porky’s father can’t afford the mortgage on the farm, Porky offers to go out and get a job, becomes a milkman, crashes the milkman’s cart and gets fired, horse gets distracted by a bucket of oats in the nearby racing stables on the way home, Porky is mistakenly entered into the race and realizes he can save the farm if he wins the cash prize, horse is incompetent, horsefly chasing horse all through the cartoon finds his target and bites horse, horse freaks out and runs laps around the track, Porky wins as a result and comes home a millionaire and sticks it to the bad guy. Simple, funny, with a clear story structure and satisfying end. No such luck here.

Rod Scribner’s animation is at least a highlight, and there’s a certain novelty present knowing Pinto Colvig lended his voice for all of the horse (and car) noises. Carl Stalling makes the best of what he can with the music score. But other than that, Porky and Teabiscuit is a standard Hardaway and Dalton cartoon, standard being code word for flop. The story is barely there (what’s happening with Porky’s father?) and the characters are unappealing and unsympathetic—a crime when dealing with such an endearing and charming character as Porky. He’s one of the very few characters whose genuine nature generates any sort of real pathos and felt sympathy; there’s very little here to sympathize with.

Porky and Teabiscuit is an easy skip. There would be better Porky horse race cartoons in the past (Milk and Money) and better Porky horse race cartoons in the future (Porky’s Prize Pony). Hardaway and Dalton continue to do what they do best, and never wields good consequences.

Nevertheless, here’s a link, and the cartoon is also available on HBO Max!

No comments:

Post a Comment