Release Date: October 21st, 1939

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Chuck Jones

Story: Dave Monahan

Animation: Ken Harris

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Dorothy Lloyd (Hens), Margaret-Hill Talbot (Chick)

(You may watch the cartoon for yourself here!)

One of Jones' more disposable shorts of the era, The Good Egg ironically features a handful of attitudes boasted by the characters that Jones would learn to embrace, refine, and manipulate to potent comedic heights: cynicism and ego.

Utterly dejected by her infertility, a childless hen stumbles upon an egg on her during attempts to literally drown her misery. Depression quickly is replaced with pride--even when a turtle hatches out of the egg instead of a chick. Though mama hen is unfazed, the barnyard chicks aren't as willing to accept their new playmate until danger strikes.

While the Blue Ribbon reissue excised the cartoon’s titles, the full opening theme of “Start the Day Right” (making its cartoon debut and serving as a recurring theme throughout the short) can be heard in The Carl Stalling Project. The music provides a bridge, carrying over from the title card to the establishing shot of the cartoon itself as we open to a farm; in spite of the muddled print quality, the painting is picturesque and warm with some particularly strong backlighting with the sun behind the barn.

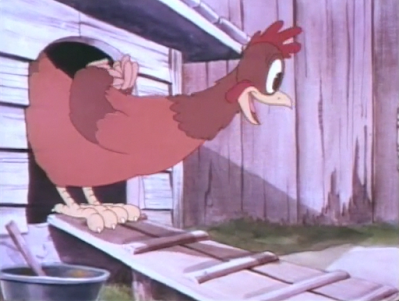

Of course, the barn is not the object of the audience’s attention—rather, the hen house as the camera pans slowly, trucks in and dissolves to its interior. A line of mother hens share contented glances as they all keep their eggs warm and sound.

Save for one. In addition to the sallow expression on the hen, Carl Stalling’s music does a great deal of conveying a shift in tone as the music steers into a more dejected direction.

Clarity of the mother hen’s situation is provided as she stands up from her nest—its vacancy speaks for itself. A tight camera zoom into her face is somewhat unnecessary, but makes no mistake in stressing her dilemma; Chuck Jones had a tendency to get somewhat overzealous with his camera movements, zooming into certain objects or characters that don’t need such extra clarification. Nevertheless, the motion is curt and provides a segue into the scene.

The opening as a whole maintains a solid parallel structure: happy mothers-to-be welcoming their chicks in the world are juxtaposed with the discouraged loneliness of the egg-less hen who can only look on.

Stalling’s orchestrations of “Start the Day Right” continue to illustrate most of the contrast, alternating between flighty and lugubrious, but the unconventionality in which the mothers hatch their eggs provides a welcome comparison to the straightforward glances of the lone hen. One mama hen cracks her egg open—another shoves them in a toaster proudly trademarked by ACME (providing the first ACME reference in a Chuck Jones cartoon!).

Animation is somewhat slow moving but solid in draftsmanship, all executed with a politely bouncy flair. Chicks tumbling out of the toaster reads as particularly well animated through its solidity and staggered, naturalistic timing—the most absurd method of hatching is saved for last.

As the childless hen makes a tearful exit, Jones places momentary focus back on the gaping, empty hole in her nest to reacquaint the audience with her plight. As will be explored shortly, this cartoon delves into material that is almost jarringly dark for the time, but somewhat sympathetic; to compare, Bob McKimson’s 1950 An Egg Scramble has the hens in the henhouse chiding Miss Prissy for her inability to lay an egg. Here, the mothers are all doting and warm and concerned with their own personal matters—feelings of inadequacy come purely from within.

Parallels, pantomime acting, and Stalling’s music score all do a very effective job at stringing together a story; not a word of dialogue has been uttered, yet the premise is unmistakably clear.

The same applies to the hen brighten up upon spotting an unattended chick. With little time spared, the chicken is quick to scoop the little guy in her arms and start “cootchie coo”-ing him.

Nonplussed, infantile stares turn into glowers from the chick as the hen coos over him with no signs of relenting. Solid acting concentrated particularly in the hand movements and facial expressions alleviate potential tedium—disgruntled reactions from the baby save the sequence from drowning in saccharinity.

Especially when a “JUUUUU-NIOR!” from off screen interrupts the hen’s fawning. With a crescendoing music sting, a mama hen swoops into frame and swipes her child out of her arms with a contemptuous glower.

While the thick, stuffy pause and pompous pumping of the mama’s tail feathers are the most obvious and amusing acting decisions, the childless hen’s disoriented head shakes as she struggles to fathom the separation (furthered through mournful finger waves to an armful of nothing after the mother departs) are equally amusing and display a great attention to detail even through the most menial gestures.

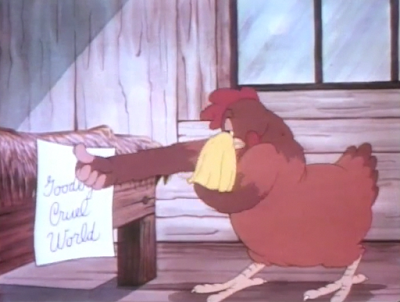

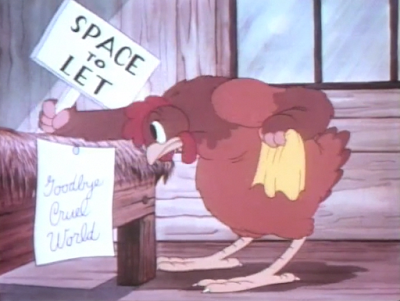

It is then where the cartoon takes a rather jarring and dark turn: reduced to tears, the camera fades out and back into the hen tacking a suicide note to her nest amidst sobs. Understanding the gravity of the premise, a compromise is wryly delivered as the hen returns only briefly to add an additional “SPACE TO LET” sign as an attempt to take some of the edge off.

Admittedly, it’s nothing we haven’t seen before. Porky’s Romance had Porky both write his note and attempt suicide on screen where such dry “reassurances” seen here were absent. Jones was also a master of dark, cynical comedy—Fresh Airedale in particular stands out as a masterclass of pure sadism.

With that in mind, it is oddly amusing to see such bleak attitudes counterbalanced by the meticulous cuteness of his Disney imitations. Whereas Bob Clampett’s cute and sadistic combination was executed with a more juvenile, irreverent energy that rendered any sadism as mischievous rather than pure bite, Jones maintains the gravity in his style of filmmaking. Amusing as the renting-out-an-empty-nest joke is, the overall tone very much feels forlorn and wholly sympathetic, if not disturbing.

Despondency from the characters and tone unintentionally leeches a little too strongly into the pacing. Though shots of the hen trudging towards the river are picturesque, there are more effective ways to convey the same grieving tone without being too tedious. Nevertheless, after a handful of pathetic waves that solidify the hen’s intents, she rushes to the river with a running start.

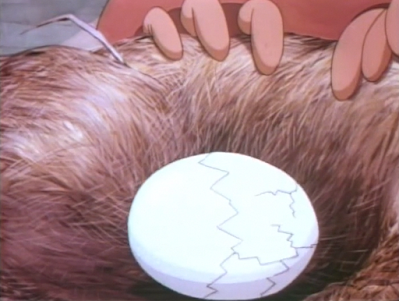

More overzealous camera moves ensue upon the hen tripping over an egg—while an over abundance of clarity is never exactly a bad thing, especially when much of the cartoon has been pantomime acting thus far, the brief truck-in and back out from the egg parallels the truck-in on Inki hiding in the tree stump in The Little Lion Hunter; somewhat meddling and unnecessary. Nevertheless, the audience is led to unanimously understanding that an egg was what tripped her and not a rock.

Furtive glances ensue as the hen approaches the egg. The joy so abundant when she stumbled upon the free range chick from earlier is nowhere to be found here—perhaps more condescending hens are waiting in the wings to berate her. With nobody in sight, she scoops the egg into her arms and flees.

Pacing on the next sequence somewhat drags and grows redundant, but for a good cause. Tonal whiplash is strong juxtaposed against both the previous scene and the beginning of the cartoon as a whole as the ever immodest mother to be clucks a celebratory chorus of “The Umbrella Man” waiting for her little one to hatch. Not only is the “WELCOME LITTLE ONE” banner behind her a staunch enough announcement, mama hen now goes through the liberty of tacking a proudly unsubtle note to the façade of the henhouse: “What local hen is expecting a blessed event?”

Elongated as the sequence may be (partially due to a shot of the mother hen knitting baby clothes—while the perspective is lovely, mama hen making a point to knit in the foreground and maintain eye contact with the audience as her braggadocio transcends the screen and into real life, there’s no reason why it couldn’t have served as the establishing shot of the scene to begin with; only that and the shot of her placing the note are truly necessary), it too serves as a subtle indication of Jones’ adoration for egotistical braggarts and smug acting as a whole. Indeed, it serves as no coincidence that the mama’s scenes in the cartoon are also the most engaging.

Additionally, scoring mama hen’s clucks of surprise upon the egg’s hatching to her continuous chorus of “The Umbrella Man” maintains consistency and overarching whimsy. Through climactic pulsations on the egg, the audience is greeted with the miracle of life.

Nobody guaranteed that the miracle of life would be cute—nor is it guaranteed that it would even be a chicken. Mama’s newborn is instead a baby turtle whose grotesqueness seems both accidental and purposeful. Purposeful in which mama’s remarks of “Isn’t he cute?” are bookended by comic pauses, accidental in which coming sequences attempting to paint the turtle as sympathetic or wholly endearing are somewhat difficult to appreciate to their fullest potential.

Nevertheless, Jones and company are able to tease the censors by showing naked baby turtle butt on the big screen as mama changes his diapers. Praises are in order for the design economy on the turtle—not only are the metal clasps on his shell akin to a coin purse clever, but the convenience in which his shell provides a censor upon mama’s recognition of their theatrical company as well. A fade to black cements a sly but naïve finality to the joke as a whole.

Moreover, it provides a means of transition to the second act dominated by the baby turtle, which scratches Jones’ cutesy tendencies more potently (and detrimentally.)

Mama hen encourages her “darling” to go play with the other little chicks, which segues to a shot of said chicks engaging in a game of soldier. Stalling’s juvenile musical accompaniment is apt, harmonious with the marching cadence from the chicks. A hierarchy is established by the lead chick touting a paper hat and sword—always a staunch indication of authority—and casting determined, quizzical glances at his cohorts to see if they’re still in line.

Early Jones philosophy prevails: to indicate the vulnerability of a character meant to be endearing, have them stumble. Still maladjusted to walking, the little turtle falls down the ramp of the henhouse and accidentally bowls into the line of marching chicks with his shell.

Bob McKimson’s animation earmarks can be seen upon the lead chick’s interrogation of this new shell: outside of telltale solid perspective and intricate angles, the wide eyed take on the chick, scramble as he struggles to put the hat back on his head and graphic marks as the turtle pops out of the shell are all synonymous with his handiwork.

“Who’re you?” The voice cast on this one is odd, as it’s difficult to pin down who exactly is providing what voice—one chick who speaks later on sounds somewhat synonymous to Margaret-Hill Talbot’s deliveries as Tommy Cat in The Night Watchman, whereas the turtle speaking towards the end of the short almost sounds similar to Berneice Hansell’s deep voice for the eldest squirrel in Robin Hood Makes Good. One thing is for certain—Jones refrains from employing Hansell’s signature squeaky, giggly voice for the chicks and turtle both which comes as a bit of a surprise.

Rest assured, the chicks are still plenty squeaky voiced, especially given their hysterical giggles upon the turtle’s declaration that he is a chicken. Jones’ close-up of the lead chick and the turtle verge on uncanny territory more than cute—though the shadows do a fine job of sculpting their respective features, with movements solid and well constructed, it feels a little overly intimate and claustrophobic. That, and the shot of the turtle shedding a tear upon being made fun of doesn’t do much to endear him to the audience; the design is just too awkward.

Nevertheless, a Sniffles-adjacent voiced chick invites the “fellas” to play pirates, prompting even the turtle to oblige in a rather quick and somewhat pushed change in mood. Likewise, a diagonal wipe to the chicks unloading in the matchbox boat seems somewhat arbitrary and slows the pacing further—wipes and transitions signify a passage of time, but the same effect would have been just as clearly illustrated had Jones merely cut from the turtle to the chicks.

One thing is made very clear regardless: the turtle isn’t joining on the excursion. Giggles and titters are copious as the turtle falls face first into the pond after the chickens shove off, prompting more single tear droplets from a discouraged turtle. While the mama hen and her baby may be different in species, their ostracism is certainly shared.

Enter act 3: The climax. As the discouraged turtle heads along on his lonely way, the camera makes a return to the chicks out at sea pond. Further overzealous camera moves are yet again reprised as a needless truck-in focuses on the box’s loosening glue—little time is wasted before the ship and its crew are completely overboard.

Oddly enough, Carl Stalling’s music score feels smug and resolved rather than panicked, his music sting conveying more of a “ta-da” and a sense of finality rather than alarm. It may be intended to serve as a dose of karma, “ta-da”ing the fact that the chicks got what’s coming to them. However, the suspense and rise to the climax feel too purposeful and straightforward to be defied by such a wry commentary.

A chorus of squeaky “help!”s as the chicks struggle to swim soon rectify any inconsistencies in tone. Much to their luck, their shrieks catch the ear of the turtle, still sulking on a hill nearby. Jones’ staging is certainly engaging; the discrepancy between the hill and the lake is certainly tangible, providing added depth to the composition, and the height of the hill and distance of the lake make it seem as though the chicks are even further out of reach and closer to immediate danger.

With that said, some showboating is included in the mix; the turtle scrambling into a running take and zooming briefly into the foreground before taking off is pure, visual fluff rather than an apt depiction of his panic.

Quick cuts between varying layouts and varying compositions further a welcome urgency and variety to keep the audience engaged. Likewise, a brief return to the drowning chicks crying for help reminds the viewer of the stakes at hand. A back and forth between the turtle and the drowning chicks is employed for this very reason—bobbing chick heads in the water are soon replaced by ripples and bubbles, clueing the little turtle to speed along faster in his makeshift turtle shell submarine.

To give credit where credit is due, a brief pause on eerily still waters as the music turns somber is a solid maneuver. Its magnitude certainly feels more genuine than much of the cartoon’s second half as a whole.

Of course, a happy end is to be expected. With all of the chicks stacked up on top of each other, they ride the turtle’s shell to safety—Stalling’s flighty, tinkly orchestrations of “Don’t Give Up the Ship” serves as a fun accompaniment.

Somewhat unnecessarily does the turtle count up his passengers. Indeed, all four are present, prompting satisfied nods; the turtle doesn’t exactly possess the same charm or charisma as characters such as Sniffles. Nods that are intended to be endearing read as forced, obligatory, and artificial.

Regardless, after a picturesque (if not somewhat dramatic shot) of the turtle and his passengers silhouetted against the sunset, Jones wraps the short in a neat bookend as a return is made to the cartoon’s establishing shot of the barn. Intriguingly, as the camera fades in, the fade almost appears to blink—the fade rises, then dims before rising a final time. As to whether it was an artistic move or technical gaffe is unclear; a clever artistic move if so, as if to reflect the bleary-eyed dawn arrival of a new day.

Truck in and dissolve to the henhouse. All the mother hens observe their children playing in the water yet again, supervision close and comfortable.

In addition to a brand new sturdy boat, said ship comes with its own lifeguard in the crow’s nest. Grand orchestral fanfares are abound as we iris out on one last wooden, slightly uncanny shot of the baby turtle.

Though certainly twisted, the first half of the short involving the mother hen is undoubtedly the strongest; there is a certain intrigue that comes with its darkness. Mama hen’s braggadocio upon welcoming her little one into the world is plenty amusing, and the parallel structure of the establishing scenes as a whole between the fertile hens and the infertile lone wolf is strong. Mama hen is a much more sympathetic character than her young’un (outside of sympathy for being ostracized in the turtle’s case)—however, to focus the short wholly on mama hen would be a wrong move as well.

Juvenile themes in the cartoon seem to breach containment and unfortunately leech into parts of the filmmaking. As a whole, the cartoon feels somewhat juvenile in a way that is grating over endearing. The turtle is a character the audience inevitably feels more sympathy towards rather than charm, and the chicks succeed heartily in being annoying.

Jones has grown considerably as a director in the past year, and the results certainly show; had this been a late 1938 short rather than late 1939, it may have been even more difficult to sit through—picturesque layouts and backgrounds, solid animation, parallels, informative music cues and amusing pieces of acting are all certainly strong benefits.

Still, the cartoon suffers from a bout of chronic glacial pacing and arbitrary maneuvers (whether something like an unnecessary camera truck-in or comically grandiose perspective animation of the turtle running around in circles.) Inarguably more novel and amusing for audiences in 1939, the overarching impression today seems to be childish and grating more than endearing and charming.

.gif)

.gif)