Disclaimer: This review entails racist content, stereotypes and caricatures. They are intended to be presented purely in a historical and informational context. With that said, I encourage you to speak up should I say something that is harmful, perpetuating, or ignorant. While never my intent, I seek to take appropriate accountability should that occur. Thank you.

Release Date: January 13th, 1940

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Tex Avery

Story: Jack Miller

Animation: Bobe Cannon

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Willie, Fox, Blackbird), Sara Berner (Mammy, Worm), Margaret-Hill Talbot (Blackbird)

Already, the shift in tone from Avery’s spot-gags to his more story focused efforts is evident from the opening pan alone. While gorgeous visuals are rife in his travelogues, often used as a deceptive means of quietude leading up to a punchline, it’s been quite awhile since an establishing pan was played straight and used wholly to inform the setting with no gag topper. Indeed, cotton fields and a muted, sleepy accompaniment of “Old Folks at Home” set a precedent for the inevitable array of stereotypes to follow.

Still, Johnny Johnsen’s backgrounds are in top form, and for this cartoon especially. Avery employs an old favorite—the multi-plane pan—which not only gives added depth and believability to the tranquil surroundings, but touches on a filmographically nostalgic note and beckons comparisons to his earliest shorts which used the same techniques. Aged film prints do little to hinder the quality of the paintings.

A truck-in and cross dissolve on the Blackbird home (a barrel shaped birdhouse) establish our characters. In this case, mama blackbird and her three little ones, here muttering a mumbling, childish, near incomprehensible prayer. Such prolonged repose from Avery at this point in time is suspicious, as he seems to be playing it totally straight. Elaborate lighting on the characters support this notion. While Avery was exceedingly conscious of his cinematography, and to great success, hardly ever has he poured such meticulous inking and coloring into his characters themselves. Much of this opening (and perhaps cartoon as a whole) feels more in Chuck Jones’ wheelhouse than Avery’s.

That is, until the birds pile into bed; their tucking in is interrupted by a quick return back to the foot of the bed and an “Amen!” before settling in once and for all—a bonafide Avery trademark. Speed is lacking comparatively in the transition, which hinders the punchline itself, but one could argue it’s more suitable for the sleepy, docile atmosphere.

As is all of the dialogue spoken in this cartoon, Sara Berner’s vocal stylings for the mama are rendered in a dialect—Avery and writer Jack Miller do not in any form refrain from pulling out all the stereotypical stops in the writing. However, Berner does manage to capture a sincerity and warmth in her intonation that seek to appeal to the tone so obviously attempting to be met. It is incredibly odd to see Tex Avery, the anti-Disney, evoke the Disney route, even if it is for the sake of exposition. Mama wishes her little ones goodnight, who do the same.

Thankfully, attempts to be more faithful to Avery’s own voice are slowly realized once the coast is clear. One lone bird rises from the depths of his blanket with the sole accompaniment of Stalling’s sly violin slide—wide eyes at the audience indicate wary yet inquisitive individuality. An idea is brewing, and an assertion to stand out indicates we’ll be following this fellow through the entire cartoon.

Craftiness with lighting effects are poured into the environments just as they are the characters themselves. In fact, Avery does a great deal of storytelling just through lighting alone. The little bird reaches off screen to turn a lamp on, whose warm glow infiltrates the room in a crescendo rather than a single frame difference. Likewise, heightened shadows projected against the headboard evoke just as much mystery and slight unease as it does coziness. Much more secretive lighting than when mama was in the room.

His intent? Reading. More specifically, burrowing himself in a book about the early bird getting the worm. From Stalling’s playfully apprehensive music score to the grip the book has on the bird, the audience is sure of one thing: a plan is in the works.

Avery’s own taste and humor make another tease as the bird flips the blankets up to rouse his brother—only to reveal his rear in the place of where his head should be. Though the joke itself is mild, expert timing and delivery in the gag render it enjoyable. Particularly the way in which the tail feathers reverberate back and forth, a staunch reminder of the switch, and the thick, judgmental pause in which the bird stares at his brother. Very natural and matter of fact pacing that speak to Avery’s strengths.

Synonymous agility in execution follows when the bird smacks his brother’s butt, prompting him to sit upright. Excessive drowsiness in the brother make for a great contrast with the accusatory, plucky tone of the bird trying to detail the content of the book.

Like Berner, Blanc speaks in a stereotypical dialect. “I say it say here, the early bird gets the worm!”

Blanc also provides the voice of the brother, channeling the likes of Lincoln Perry's Stepin Fetchit character as he dismisses the book as nonsense. While his slow movements and drawl are birthed from negative stereotypes first and foremost, it does admittedly establish a strong contrast between the main bird and his brothers, a plucky and adventurous outlier—a theme that traces back to some of Avery’s earliest works like I Love to Singa.

Lighting continues to play a great part in storytelling as we switch to mama blackbird heading to bed. When she turns her own light out, lights visible from the other room shine through the cracks in the door, indicating that her children aren’t being obedient. Intricate double exposure effects convey a warm glow, which allows the lighting to feel natural and cozy more than opaque yellow or orange paint would. Smart, clear, informative.

Likewise, mama’s entrance into the bedroom is informed wholly through sound effects off-screen. Just through the creak of a door alone, the little bird (whose mama reveals his name to be Willie) hides the book behind his back. Concealing her face until the last minute—substituted only by a telltale finger wag and her voice over demanding Willie hand over the book—births a greater sense of looming authority.

We do eventually see her face, the camera panning left to account for her throwing the book out the window. Even if the maneuver is merely to get the prop out of the scene, its execution is relatively anticlimactic and stiff, the book seeming to float out the window before disappearing entirely. No sense of weight nor force in the throw.

Regardless, priorities are delegated to her acting. Primarily warning Willie about the dangers of catching the worm—“The ol’ fox will catch you!”

In a clever maneuver, the camera cuts to all three children now wide awake in bed. Staging previously was articulated so that only Willie was visible in bed, allowing the sudden consciousness of his brothers to feel more spontaneous and engaging. Inquisitive head turns to each other are exchanged before a simultaneous declaration of “The fox? What’s that, mammy?”

Her dramatized descriptions of the fox is one of the more inspired portions of the cartoons, carried through Berner’s intonations and imaginative posing. When she indicates the fox’s height, her arm stretches out of frame, providing an added exaggeration and making her gestures seem even more broad. A note of big eyes prompts her own peepers to fill the circumference of her fingers. “A long, pointed nose” results in mama extruding her beak accordingly, reverting back to its regular shape in a very nonchalant delivery as she details the sharp teeth next. It becomes somewhat difficult not to fantasize about how distorted or exaggerated these portrayals would be had this been under Avery’s MGM tenure, but it works here.

Of course, the real kicker arrives only when mama makes it personal: “An’ he just loves to eat little birds… just like you!”

A rapid camera pan to the right and Stalling’s musical accompaniment accenting the final three words give a playful gravity to the threats. That, and the frenetic scrambling beneath the covers that unfolds. Shooting the scramble on ones—as well as generally loose, if not a bit formless, drawings—are much more reminiscent of Avery’s true timing and taste when not shackled by Disneyesque influence.

More somewhat elaborate lighting effects as the kids are left on their own for the night. Willie daring to cast a quick glance to his brothers is a cute, informative detail, as if to gauge if they feel the same petrification he does. Not only that, it continues to encourage that he’s the odd one out, asynchronous from his decidedly synchronized siblings.

Indeed, Willie reiterates that he’s unafraid of the fox and plans to wake up early to catch the worm. Vocal direction on the brothers is inconsistent, as they now both seem to be voiced by some of the female regulars at the studios rather than the Fetchit-esque minstrel dialect from Blanc. Further divides between Willie and his brothers are established as the siblings repeat their mother’s warning: “Yeah, and the fox’ll get you!”

We close out on a surprisingly sentimental note, something not quite felt from Avery since 1936 or 1937. At least, not in a way that wasn’t topped off with any sort of wry or mischievous commentary. Instead, Willie merely dismisses the concerns of his brothers, sets his alarm, and goes to sleep—Stalling’s musical orchestrations do much to sell the warmth. An unconventional for Avery’s standards clock transition is our last look before the screen fades to black.

A part of why this cartoon feels so retroactive is that it uses primarily two previous Avery cartoons as a base. Whereas future segments channel the more playful, witty, fast-paced mischief of The Sneezing Weasel, this particular sequence dedicated to Willie waking up and sneaking out of bed almost directly mirrors a similar sequence in I Love to Take Orders From You. Even the quick “Amen!” gag was lifted from the same short. In tone, intent, and general execution, both are synonymous—thankfully, Worm has the benefits of much more refined draftsmanship, filmmaking, and speed.

Johnsen’s background painting depicting the dawn sunrise is nothing short of gorgeous. Intricate reflections of nearby houses are projected in eerily still waters, the sky is hazy yet warm, drowsy, and the dark tones of the surrounding trees provide a great contrast to the glow of the sky. Strategic arrangement of trees in the foreground (and the Blackbird home itself) form arcs and frames all around the composition that naturally appeal to the eye and engage, without being distracting at the same time.

Willie’s shushing the alarm clock as it rings is not rooted in the influence of Orders, and is yet another one of the most inspired gags the cartoon has to offer. All due to bold, nonchalant deliveries that do little to call attention to themselves.

Sneaking along the hallway and past his mother’s room is where comparisons to Orders grow more concentrated again. Thankfully, Avery has the benefit of being a director for nearly 5 years, whereas Orders he didn’t even have a full year. Ample time has been allowed to perfect speed, pacing, where to place emphasis for the strongest impact and so forth.

Therefore, in signature Avery brilliance, Willie tiptoes to the doorway of the room, darts past it as a a streak of paint flashed for only a few frames, and continues tiptoeing as though nothing had happened. Sandwiching the rush with the slow movements emboldens the speed through a means of comparison. Much more effective and humorous than the very straightforward execution in Orders, as well as a brilliant example of how much Avery has improved just by revisiting the same setup.

An equally intriguing maneuver is executed when Willie accidentally falls from the perch outside their home. In an attempt to maintain furtiveness, he creeps backwards out the door, misjudging the amount of space he has to cover and plummeting to the ground. Amidst the fall, one particular pose is held for three separate frames, with the background still panning—the fall almost feels more disoriented, unpredictable, and weighted, a stronger jolt in the chest than what would be felt through mere tumbles. A drumroll in the background provides its own playful commentary rather than a tone of impending doom.

For all of the cartoon’s tonal anachronisms and comparative archaisms, Avery does top off the fall with a footnote he would reuse multiple times—The Heckling Hare and MGM’s Dumb-Hounded being a few. Rather than turning into a puddle of bird flesh, Willie manages to find his balance and jut his feet out, prompting a braking stop just before the ground. While the gag would be perfected as time goes on, with Hare having the benefit of actual brake sound effects and the meta humor of the Dumb-Hounded’s wolf commenting “Good brakes”, for a start the joke here is nevertheless conveyed clearly, benefiting from the grandiosity of the drumroll.

Hat follows similar physics.

Thus spurs on the second arc of the cartoon as Willie prepares to hunt his prey. In typical Avery fashion, hunting metaphors are taken to the extreme as Willie bends to the ground and sniffs like a hunting dog—The Crackpot Quail and The Heckling Hare would both expound on further ridiculousness through the courtesy of Willoughby, perhaps one of Avery’s most self indulgent (yet delightfully so) creations yet. For now, the disconnect between species is enough of a joke in itself, and frantic sniffing sound effects greatly benefit the illusion. The Disneyesque visuals so painstakingly established in the first act are maintained through foreground overlays of various wildflowers and grasses.

So enters the worm, his introduction nothing more than jumping out of a hole. A single buck tooth and decidedly Mickey Mouse adjacent clothing solidify him as the screwball du jour, as well as a worthy adversary—such a level of anthropomorphism wouldn’t be delegated to any old worm otherwise.

Musical theming is a strength between the two characters; whereas Willie is scored with a triumphant accompaniment of “A-Hunting We Will Go”, the impending antics of the worm are hinted at through a childlike, jovial theme of “Ain’t We Got Fun” (also a Merrie Melody directed by Avery that was more archaic in its tone). Convenience of Willie’s discarded book by the wormhole, detailing the inspiration behind Willie’s mission, is almost comedic in itself through such bold, unabashed accessibility.

Like Willie, the worm speaks in its own high pitched dialect, telling the audience he’s going to check out the early bird for himself. Synonymous sniffing and hunting of tracks ensue.

It is here where the musical theming between the two characters grow the strongest, juxtaposition bold as the camera repeatedly cuts between the two characters, their theme songs changing with each cut. Repeated cutting indicates a growing collision, as there is only so much ground to be covered until the two cross paths.

Sure enough, the inevitable occurs, both characters forehead to forehead as the audience can practically see their thought process on-screen. Avery maintains parallels between the two outside of the hunting metaphors—both engage in a rather mushy, gelatinous yet mirrored surprise take before running off screen.

While Avery has been comfortable in his speed since the very beginning, these past few cartoons have especially had particularly inspired moments. That Willie and the worm depart the screen through only one frame, a mere trail of brush streaks at that, parallel the perils of Gregory being thrown back into the bench in Screwball Football. Enabling both characters to slowly scramble into place before making a rapid departure allows the exit to linger, like the after effects of having one’s picture taken. Great incongruity in varying speeds and even greater unity between the mirrored actions of the characters.

Mirroring continues as the two run in complete opposite directions, the worm possessing the added benefit of brush trails. To make use of the outdoor surroundings, Avery has Willie hide behind a toadstool. An apprehensive sting of “A-Hunting We Will Go” as he peeks his head out reminds the audience of his identity and his mission.

It also reminds Willie, too. Determined to act on his bravery, he scowls, shoving his hat forward on his head to indicate serious business. He barely has any time to charge forth before Avery cuts to the worm, effectively enhancing his speed in the result. Miraculously, clarity remains unhindered.

Foreshadowing to the eventual rechristening of Ben Hardaway’s rabbit has been hinted at through a number of cartoons already, but the next bit may very well be one of the most formative. To escape its pursuer, the worm dives into the sanctity of his hole. A frustrated, gutsy Willie skids to a half to effuse many a threat and insult into the hole…

…only for the worm to pop out of a nearby hole and contribute to Willie’s curses. A maneuver synonymous to Bugs Bunny that Avery would establish as early as A Wild Hare, the worm indeed does take on a number of qualities possessed by the soon-to-be-realized rabbit. Playful cockiness, an adoration of heckling and an invincibility that comes as a chagrin to any nearby antagonists. Of course, the worm doesn’t possess nearly the same charisma as the rabbit, but that’s somewhat of a given.

When the inevitable realization strikes, Avery somewhat subverts expectations in that the worm is just as surprised as Willie is, again mirroring his movements before running off. No smooth talking or attempts to pull it off. A tactile snappiness in the animation, especially when the two jerk their heads to look at each other, elevate the playful urgency and orchestrate a threat that doesn’t feel artificial.

Further Bugs Bunny-isms are realized from the worm after Willie’s fruitless search in a pile of nearby junk. Kudos to Avery and company actually using the painted background as a prop and having Willie stick his head inside the cans, crawl around, and so forth—it becomes easy to forget that the backgrounds were entirely separate layers and that the animation drawings had to be cut off at a certain point to accommodate for the shape of the props. Generally frantic, comedically aimless histrionics from Willie’s movements maintain much needed pep and appeal to Avery’s penchant for speed.

Not only is the worm’s claims that the worm ran the other way indicative of synonymous cartoons with greater refinements later on, the punchline is too. This isn’t the first sucker gag we’ve seen in a cartoon—that honor goes to Ben Hardaway and Cal Dalton with Gold Rush Daze—but it is the first where it’s explicitly meant to shine a humiliating spotlight on a character, embarrass them in front of the audience rather than a passing declaration.

Willie comes to a running stop, his brain finally catching up to him before transforming into his insulting, metaphorical fate. Whereas most gags of this kind have the lollipop substituting the subject entirely, Avery keeps it grounded in that only Willie’s head his truly gone, his body still remaining in a transparent overlay. It almost seems crueler that way, reminding the audience of the face behind the sucker and ensuring everyone knows it is Willie subject to such ridicule. Even if this isn’t the first variation on the gag, most that followed were much more synonymous to the setup established here.

More chasing ensues, this time with the worm seeking refuge in a nearby flower. Carl Stalling’s musical accompaniment is fine tuned to the action, not particularly bound by any one overarching piece of theme music—a trend that would soon be the norm for his arrangements as a whole. Avery particularly seemed fond of how the music could be a guide and propellant for the animation rather than a backing track, as Stalling’s orchestrations at this time are the most behavioral in Avery’s shorts.

Idle movement of the flower still bobbing upon Willie’s entrance indicate the lingering presence of the worm. After a quick search, he realizes as such, opting to stick his hand in the depths of the flower.

Furious buzzing noises ensue as he is ruthlessly jostled around by the flower, resulting in a particularly intriguing running take; mimicking a similar maneuver in Hardaway and Dalton’s It’s an Ill Wind, Willie takes off running, a double exposed image of himself still paralyzed in place before fading moments prior.

Whereas Ill Wind swapped which properties were double exposed (in this case, Dizzy’s conscience was the one who fled, his flesh and blood self being the one struck by paralysis), the route taken here conveys more of an afterimage in an attempt to caricature the pure speed in which Willie departs. He doesn’t run out of frame as fast as he could, rendering the maneuver a little more busy and lessened in its impact than what was intended, but is still very clever and inspired regardless.

Of course, it was all a dupe, indicated by the worm’s joyful buzzing as he poked his head out of the flower. One can almost hear the nasally chuckles of one Bugs Bunny now.

A whistle prompts Willie to make another return, racing past another flower that bobs in the same (albeit much more stilted and cycled) way. Squeaking brake sound effects offscreen indicate Willie has become wise—indeed, he returns, wasting little time in diving into the flower itself. While so much of the chase has been incredibly repetitive thus far, little differentiations such as Willie jumping into the flower rather than reaching with his hand a second time give each gag a little bit more identity and juxtaposition.

Especially considering that this time, an actual bee throws Willie out of the flower. Fist shakes are polite comparatively, almost begging some sort of incomprehensible, high pitched rambling to simulate cursing, but the manner in which he tosses Willie’s hat on his head is a great indication of his disgruntlement regardless.

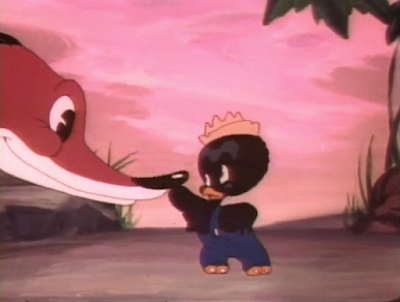

The beauty of Tex Avery is his self awareness. When the worm whistles at Willie to spawn another chase, Avery appears to comment on the repetitive and circuitous nature of the cartoon by entering the third act: the true villain. Thus, we meet the fox.

Much of the next third of the cartoon is derivative of The Sneezing Weasel, the fox posing a very similar role next to the eponymous weasel. Avery’s adoration of self-congratulatory villains manifests through the fox introducing himself directly to the audience through the aid of signs. While such villainous introductions have been an Avery tradition since 1936 (Milk and Money, Uncle Tom’s Bungalow being a few notable examples), the fox’s declarations of “THE VILLAIN — AS IF YOU DIDN’T KNOW” would be reused directly in Aloha Hooey, a cartoon Avery began production on before heading to MGM, where it was then completed by Bob Clampett.

Thus, comparisons to The Sneezing Weasel are solidified when the fox joins in on the chase—Willie, noting his company, asks if he’s trying to catch the worm as well. After some unconvincing throat clearings and an incredulous stare into the camera, the fox goes along with the act, similar to how the weasel pretended to be a doctor and earn the trust of the baby chicks in the former. Stereotypical dialects are delegated to the fox’s speech mannerisms as well.

It’s certainly fascinating to compare the drawing style of the two villains—the weasel is much more geometric, rubbery, streamlined and decidedly Averyesque in design through his simplicity. Here, the fox looks like a runaway from Robin Hood Makes Good, further clinching comparisons to Disney and Chuck Jones. Out of all of the characters in the film, the worm seems to tout Avery’s artistic sensibilities the most. The fox doesn’t have a bad design by any means, but he doesn’t feel as though he lives up to his true villainous potential—Tex Avery villains are hard to beat.

A lengthy dialogue sequence is thus dedicated to Willie getting chummy with the fox, commenting on how the worm is a “tricky li’l cuss” before repeating his mother’s warnings about the fox. The fox’s feigned interest, reeking of disingenuousness, is great. Regrettable as Blanc’s performance for Willie may be with such a dialect, he does capture a plucky naïveté and youthfulness in his intonation that furthers any sincerity to be had. Mimicking the same gestures about the tall height, big eyes, pointed nose, long teeth, etc. provide a solid bookend and parallel to his mother’s warnings. Especially as with each descriptor, he comes to the creeping realization that he’s conversing with the enemy in question.

Even though he himself knows it’s too late, Willie attempts to flee through a good ol’ feigned sleepwalking exit. Dripping sardonic commentary is provided through Stalling’s slimy violin slide in the background. An inevitable climax is hinted at…

…and realized when Willie flees out of scene. Avery’s knack for speed comes in great bursts such as this one—the creeping build-up is satisfyingly topped off with an antithetical rush of speed, creating a much more urgent sense of motion and contrast that is clear and engaging. Likewise with the fox propelling his arm forward to snag Willie in his clutches.

In a twist, the worm—in all of its gregariousness—decides to help its own predator while Willie screams in the background. A close-up on the worm thinking is a bit extravagant and unnecessary, seeing as he’s perfectly visible from the starting distance as is, but the maneuver rightfully places the worm in a more sympathetic lens. We are expected to give him our attention.

So, with that in mind, seemingly menial aspects of the chase prior are employed for the greater good. That is, the worm violently shakes the flower in which the angry bee is residing in. Props to Avery and company coloring the worm’s pants red; as he shakes his rear to provoke the bee into stinging him, the red color substitutes the provoking red cape used in bull fighting.

A very brief and somewhat bloated shot of the bee chasing the worm is flashed before cutting to the fox, a curt little reminder that a plan is in the works.

Plans are in the works with the fox, too. Another somewhat unnecessary camera truck-in is delegated to the fox unearthing ketchup from his flesh pockets; at the same time, it guides the viewer to understand that it may play an important role later on. At least, important enough to distinguish itself from the two slices of bread the fox has jammed Willie between.

Repeated cutting back to the bee and worm—much like the cutting between Willie and the worm during the latter’s introduction—indicate an impending crossing of paths. Avery does a nice job of varying the staging for the shots involving Willie and the fox, with one a wide shot, the next a close-up. Nice juxtaposition against the consistent, horizontal pan shots of the worm outrunning the bee.

At last, while the fox is preoccupied with his meal, the worm manages to land on the fox and lift up his tail. He continues to provoke the bee by shaking his own ass in its face—having the bee exit the frame entirely in preparation for the sting exaggerates the tension, the force of the sting. Likewise with a drumroll in the background.

In signature Avery fashion, a joyously excessive amount of speed and ferocity is exerted on the sting itself. Comparable to similar scenes in Milk and Money where a horsefly stings Porky’s horse, Avery has since fastened a much more visceral handle on speed and how best to time/space the animation drawings out for maximum impact.

Mel Blanc’s voice acting proves beneficial as well; while an echo is almost always inherent to his every scream thanks to the stage on which he recorded lines, a heavy reverb enables the echo to linger for seconds at equally thundering volume. The effect is almost haunting in that it represents the fox’s screams lingering in the air, seeming to manifest as a physical object in itself. Willie and the worm take cover in just enough time for the fox to come crashing back down to earth.

Same with the ketchup. Admittedly, a certain suspension of disbelief is required to fully appreciate the fox’s blithering screams about how he’s bleeding (perhaps landing on the bottle to begin with and breaking it, looking as though he’s been stabbed in the chest rather than just having the bottle crash on his head), but the sheer gruesomeness of it all is very much enjoyable. Frenetic vocal performances from Blanc and large, grandiose posing on the fox all make it a success. Enabling his “blood” covered gloves to jut out into the foreground in perspective is as fascinating and engage visually as it is horrifying.

And, with that, our villain departs, just in time for Willie and the worm to make amends.

Well, almost.

Avery has exhausted his need for chase and trusts his audience to put the pieces together. Instead, we dissolve to Willie climbing back into bed—kudos to Avery for not abandoning the exposition of the cartoon. Instead, the alarm clock rings, prompting a profusely sweating Willie to take cover and feign sleep.

The hat, too.

Enter mama blackbird, who coos at her “sugarplums” and asks if they all slept well. She is met with resounding yesses…

…even if Willie’s is considerably more exhausted from his turmoil. The parroting, synonymous staging of the remaining brothers allow Willie to stand out further, always following the rule of threes. His brothers are mere devices to shed more focus on the differentiation of Willie, but it works well.

Such is used to an advantage upon inquiry of what the kids want for breakfast. A resounding declaration of “Worms!” come from the brothers…

Still worn from his earlier turmoil, Willie declines his offer for worms, sounding thoroughly sick.

His worm friend agrees. To Avery’s success, there are positively no indications that the little worm has been residing in the bed, which makes his reveal all the more satisfying as a surprise.

Especially when we iris out on him slapping a hand to his mortified face, coming to terms with his inadvertent sacrifice.

.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment