Release Date: January 6th, 1940

Series: Looney Tunes

Director: Bob Clampett

Story: Warren Foster

Animation: Izzy Ellis

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Porky, Daffy, Bull, Duckling, Chick), Robert C. Bruce (Customer), The Rhythmettes (Chorus)

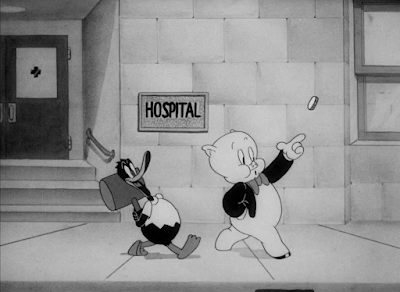

To officially christen the new decade, we ironically open on old habits; Disneyesque tranquility is conveyed through strategic planning of the establishing shot, Dick Thomas’ signature foreground trees forming a natural frame that arcs around the eponymous food stand. That in itself brings more old habits of Clampettian wordplay—in this case, a pun on fried chicken tasting fowl, and the Custer's Last Stand appropriation.

Like so many other establishing shots synonymous to this one, the tranquility is all a purposeful ruse. While stagnation is meant to provide the audience with ample reading time, the lack of activity is almost suspicious, too good to be true. A breach of decorum, a flurry of movement, any sort of interruption is bound to erupt—these dawning flutes and warmly anticipatory strings in the musical orchestration certainly can’t be intended in the utmost sincerity. Not with Bob Clampett at the helm.

Sure enough, hesitancy in the authenticity of the setup is validated through the unapologetic overzealousness in which the food stand opens for business. Perhaps “comes to life” would be a more apt description—maneuvered through an elasticity in the motion that is admittedly unnecessary yet confident and proud in its arbitrariness, the roof launches itself from the sides of the cart and brings new life with it.

Hens are summoned out of thin air and nest comfortably on the curving roof. Stools from inside the wagon are tossed into place right by the window. Even a customer is thrown into a seat from within—it’s as though every single ingredient to the making of a bustling food stand was ruminating purely within the stand, waiting for the perfect time to be set off and explode into place. An biding energy hungering to explode. A representation of Clampett’s philosophy, the “breakout” theory he mentioned himself, how a tangible sense of tension is best to propel the inherent rewards that come with it.

Innately Disneyesque visuals and establishment beg actions rooted in logic, believability. Dedicate a sequence to Porky setting up the food stand that so proudly touts his name himself, gathering the hens together and greeting his customer good morning. No, instead Clampett follows a much more spontaneous and deliberately caricatured root that intends to jar the audience from such misleading preconceptions. Why are there chickens on the roof? Where did that customer come from? How is the food stand sentient? To question it is to deny it—the elasticity and motion is conveyed with such conviction that we have no choice but to be enamored by the unorthodoxy of it all.

The camera truck-in—and, subsequently, the animation—to the chickens swaying back and forth singing is crude, liberties taken to accommodate for the small size at such a far distance. Yet the rigidity, jittery motion and simplicity seem to benefit the energy more than hinder it. Compensation is soon delivered through a cross dissolve regardless.

More close-ups require more snarky signage, this time gregariously titling the hens as dead-end. Signage is thankfully not the priority of the sequence; rather, the hens clucking a discordant chorus of “Start the Day Right”. Attention is intended to be directed towards the pompous posing on the chickens clucking their shrill hearts out, embracing the juxtaposition between confidence and singing skill, but the sign strategically placed in frame provides an extra incentive.

Even the eggs conveniently positioned on the roof serve a purpose outside of decoration. With each syllable of the chorus, the eggs hatch in succession and contribute their own, high pitched vocals: “Ho!” “De!” “Lay!” “Start!” “The!” “Day!”…

A pause. A belabored pause, in fact—that the backing music halts completely allows the suspense to feel more palpable, tension much more thick as the camera slogs towards an unhatched egg strategically placed away from the cluster.

Had the chicks stared accusingly at the unhatched egg, some of the suspense would be lost; that nobody appears to react, instead clinging to the stillness that dominates the moment, the disruption feels more spontaneous and less orchestrated than it would if there was a beat filled with an anticipatory drumroll or glare from the chicks.

Instead, such glares are shared after the egg hatches, a duck—rather than a chick to promote further disenfranchisement—shrieking a shrill, discordant “RIIIIIIIIIIIIIGHT!” Shared glee and fervor in both Blanc’s delivery and John Carey’s animation enable them audience to revel in the ducklings’s shamelessness.

With that, a pan. Allowing the camera to pan downwards before dissolving to the interior of the stand supports a stronger tactility and motion, momentum, as though the audience themselves are actually traveling inside. Such an effect is much stronger than it would be with a mere cross dissolve sans camera movement or jump cut.

The introduction of Porky jovially slapping carefully constructed stacks of batter onto the griddle in his unorthodox pancake making methods gives way to the body of the song’s chorus. Voices courtesy of The Rhythmettes are sped, but not to a distracting degree—thanks to the introduction of the chickens, the pitchiness of the music almost seem to convey some sort of ethereal chicken chorus singing off-screen, even if the deliberate clucks in the scene prior are absent. Almost akin to Snow White or any sort of ambiguously Disney influence. It feels bright, flighty, chipper, reflected in the musicality of Porky’s pancake smacking.

Musical timing is solid, a priority, but not in a way that feels overly conscious or meticulously orchestrated. Perhaps a part of that is due to the slightly asynchronous timing in which Porky bobs along to the backing chorus; it isn’t as obedient to the orchestrations as the smacking sound effects of the spatula, but isn’t egregiously out of tempo to warrant harsh criticism. It adds to the slight, familiar imperfections that makes Porky so endearing, even if it wasn’t the intention.

Familiar imperfections of endearment are soon to be realized in a way that is intentional. Eye contact with the camera upon the arrival of the chorus indicates that Porky is going to interject his own contribution to the song. Purposeful cuteness and overall pleasantness in his demeanor are both honest and used for deception at the same time; the audience is somewhat deluded into thinking his chorus will be cute, fine tuned, the cherry on top of the saccharine sundae that is the opening.

So, with all of that preparation in mind, the only logical explanation is to veer to the opposite. Porky’s shrill, boisterous cry of “HO-DE-LAY ehs-ehs-START TH’ DAY th-th-RIIIIIIIIGHT!” will forever be one of my favorite deliveries to come from the mouths of both Porky and Mel Blanc.

It isn’t even a matter of his stutter getting in the way; listening closely reveals that he lags just a millisecond behind the chorus to begin with—a very purposeful decision—though the stutter certainly does help in strengthening the discord. Rather, the pure confidence and uninhibited joy that exude from both the character on screen and voice actor behind it completely tie the scene together. It is pure joy and pure oblivion—oblivion on Porky’s side, who shows absolutely zero indication of any sort of self awareness to his caterwauling.

To the credit of Clampett, Blanc, and Warren Foster, the almost anarchic joy in which Porky completely defies the expectations of the audience make him all the more charismatic and cute rather than something to sneer at. Refusing to allow a beat dedicated to an embarrassed follow-up or any semblance of self consciousness plays a major role in this—if Porky were to coyly blink at the audience or grow bashful, it would indicate something to be embarrassed about, a concession, a lack of conviction that indicates such antics should be laughed purely for the sake that they are disruptive and embarrassing, rather than a charming piece of insight into his character.

Thankfully, no such lack of confidence is delivered. The camera merely pans towards the next beat of business, ending on the note of Porky’s infectious grin. A grin that speaks for absolutely everything—the sincerity of the scene’s entire delivery is what makes it such an absolute powerhouse. Much like his introduction in The Film Fan, struggling to remember his shopping list, this brief scene represents everything I positively adore about Clampett’s Porky and vision as a whole.

Musicality continues to be keenly noted and upheld; even the camera pan follows the bridging string descent from the orchestra, promoting a transition that is natural and smooth.

Daffy’s entrance comes as a surprise. The “Starring PORKY and DAFFY” title card shown at the beginning of Scalp Trouble and Wise Quacks has been retired, and the signage on the food stand doesn’t say “PORKY AND DAFFY’S LAST STAND” or make any other form of acknowledgement. In the same breath, Daffy has solidified his place as Porky’s sidekick, and audiences have come to associate the two together. His appearance may come as a surprise initially here, but not one that at all feels out of place. Instead, it feels right at home.

In the way that Porky’s deliberate cuteness aimed to invite a more brash antithesis, Daffy’s disarming quietude and obedience in which he washes the dishes surely hint to an inevitable catharsis of unbridled insanity. While he has made great strides towards coherency and sanity in his past handful of appearances, the pleasantry here feels artificial and suspicious knowing both Daffy and Clampett’s adoration of screwball hysterics.

Demonstrations of Daffy’s drying methods begin to steer towards a more predictable, less purposefully sterilized direction. Similar to Porky drying himself in Polar Pals, the musical orchestration succumbs to a rhythmic Samba arrangement to account for the rigorous motion in which Daffy dries the dishes with a rag tied around his rear.

Water droplets flying from the dishes indicate effectiveness at the peculiar methods, which almost makes them seem even more absurd through such a grounded little detail. Somewhat vacant but acknowledging eye contact from Daffy to the audience seem to poke fun at any doubts the viewer had, both in terms of the eerie obedience in his dish washing and potential lack of efficacy in his drying methods. We have been duped.

Stalling’s musical prowess establishes just as imposing of an influence on the scene’s outcome as the animation and motions themselves. After each verse, the music halts entirely to account for the suspense of Daffy flipping the plates off his ass and stacking them on a nearby counter. Not only does it establish a momentum that is coherent, a pattern, a visual and musical aid for the audience to digest the routine, but it continues to prove the viewer wrong and ground the action by giving a spotlight to the sound of the plates clinking together. Sounds of clinking together rather than sounds of china smashing to the floor. Indeed, no matter how whimsical or absurd, Daffy’s methods are effective, and we are almost meant to question ourselves rather than question the validity of the unorthodoxy. Embrace the unconventionality first and foremost—to question is to distrust.

On a less expatiating note, the animation and drawings themselves all receive the same praises of maintaining clarity and rhythm. Silhouettes, lines of action, and arcs are all prominently and proudly touted to further the snappiness, smoothness, and overarching visual appeal. Very few characters could enable a plate to slide down their back with the same simplicity and coherency as Daffy—the natural curve in his body and elongated neck provide a comfortable buffer for the plate to slide down with little to no bumps. Likewise, tail feathers complete the arc in the line of action and make for a very tidy and focused presentation as a whole.

Formula has dominated the entire opening of the cartoon thus far. That is, each and every beat has subscribed to the rule of threes: two shots were dedicated to the singing hens before revealing the shrieking duckling, Porky’s own interjection was only after two beats dedicated to smacking the pancake batter. Now, Daffy dries two dishes before engaging in his next act, the punchline, the breakout.

Even the timing and spacing in the animation of Daffy grabbing a nearby stash of various dishes is indicative enough of a shift—a certain amount of deliberation, purposeful, grandiosity in the flick of his wrists indicate preparation for an oncoming resolution.

The crossed, joyously vacant eyes that grace Daffy’s face is one of true catharsis, a sign that any and all pleasant façades are buckling in favor of the hysteria itching to break out. That, and the reckless maneuvers in which he swings the teetering stacks of fine china back and forth in tandem with the music. Not even to score the musicality and contribute to the song number so much as it is a means of gaining momentum, psyching himself for the ever approaching explosion, the stretches before the running start, the hops before leaping off the high dive.

Success not only resides in Daffy’s facial expressions, maintaining vacant, crazed eye contact with his viewers the entire time, but both the animation of the plates themselves and the sound effects in which they clatter together incessantly. With so many plates crammed together in such a small space and moving constantly, maintaining rigid consistency is out of the question. In fact, the busyness of the plates themselves benefit and speak to the simmering freneticism so desperately trying to creep its way forth. Continuous clattering sound effects remind the viewer of what’s at stake, that these are real objects with real purposes that will face real consequences from crazed misuse.

Daffy’s throwing of all the plates in the air is an act of pure and utter catharsis. The breakout. It scores the musical crescendo perfectly, reaching its harmonized climax in the background, the act dictated by uninhibited impulse but maintained and strung together through musical awareness.

Restlessness even dictates the way he moves—the jump into the air and slight refusal to settle into any singular pose held for more than a second are all means of rebelling against the purposefully restrained dishwashing seen at the scene’s introduction. Even when he lands on his feet, his arms continue to wave frantically as though inviting the downpour of dinnerware to come crashing down upon him. Like Porky’s oblivion at his terrible singing, the breakout finds its success through total conviction to the act and a lack of any beats or reactions that seek to note self awareness or questioning. Whether he fully realizes the consequences or not, Daffy wholly welcomes them regardless.

Holding a key pose for a single frame before removing Daffy entirely and replacing it with the stack of broken china engulfing him allow for a jarring, abrupt transition that isn’t muddied through an obligation to keep things smooth and pretty. Weight is a stronger priority, as is feeling—even if some of the singular plates raining down themselves do seem weightless and misguided comparatively, the bulk of the dishes do not. Ending the song right then and there with no lasting music cue further collaborate with the jarring interruption.

Restraint on Clampett’s part make for a more fulfilling end product. Had this short been made two years prior, the exposition to the climax wouldn’t have nearly been as meticulous, methodical, nor silent—“HOO HOO!”s would be aplenty. While such trademark shrieking is never, ever a means of complaint, it is an easier route to default to than restraining any and all communication purely to facial expressions and context clues. Even if he doesn’t say a word, he is plenty communicative, his utter joy at reaching the plate shattering catharsis transcendent and infectious. Slowly allowing dishwashing, drying, and breaking methods to grow more egregious as the momentum gathers ground make for a much more rewarding end product.

Keeping this in mind, Clampett does strike a nostalgic note; Daffy rising through the depths of the shattered china completely unscathed, broken teacups dangling from his head and beak respectively as a reminder of his deeds all mirror a sequence in Porky & Daffy; particularly where he breaks a bed in the midst of his imaginary boxing match and pops up from the wreckage.

Comparing the two scenes back to back illustrate the praises sung here regarding Clampett’s restraint and growth—while the former example is absolutely rife with energy and mischief, prompting some joyously elastic animation from Chuck Jones, the restraint here doesn’t feel nearly as aimless nor self-indulgent on a surface level. While still very much a victim of his own impulses, and will continue to be for decades and decades to come, Daffy does feel somewhat more refined, intuitive, communicative and easier to read than the former, where he is essentially a brainless vehicle for screwball hysterics to occur. Again, like most things, there is no right or wrong approach, and both sequences are fantastic, but it is rewarding to track Clampett’s growth and the solidification of these characters in such a short span of time.

A quick addendum: background details are given slightly more relevancy in this cartoon than others. Glances at the background reveal a trash can already filled with what appears to be bits of shattered dinnerware—an indication that this is not nearly the first time such an incident occurred. Small and seemingly inconsequential of a detail as it may be, it evokes a story and establishment in the setting. The viewer defaults to questioning; when did this happen? How often does this happen? How many plates do they go through in a week? Does Porky know or even care? While no such questions are meant to be thought about in excruciating detail nor answered, that they are even beckoned at all means that the storytelling is engaging and clear. All of this can be gathered through such a menial detail.

Intentional or not, that we can hear the ominous beginnings of a customer pounding his fist before before the completion of the cross dissolve or resuming of music already speak to his imposing nature. Musical timing is still a solid, inspired anchor, as his pounding soon scores Stalling’s ever appropriate accompaniment of “I’d Love to Take Orders From You”. Only granting the viewer the privilege of his silhouette and beefy fist seek to heighten his intimidation and nebulousness—we don’t know much, but we do know that he is a figure of authority.

A deliberate delicacy is exercised in Daffy’s entrance as he finishes putting on his uniform. Animated by John Carey, the motions are smooth, flowing, somewhat flighty and deliberate, all a stark contrast to the reckless, impulsive deliverance just moments prior. Having Daffy enter the scene with the coat and hat already halfway on again further believability of the characters and situations. It’s a gesture that feels natural in its pacing and decision, much more than if we were met with an arbitrary spotlight dedicated to Daffy getting dressed. The audience is trusted to read between the lines.

“Well, whaddaya have, chum?” Momentary issues with the double exposure accounting for the silhouette prompt Daffy to turn transparent for a frame, but is hardly visible in motion.

Robert C. Bruce steps out of his typical typecasting as condescending narrators and instead provides the overbearing timbre for the equally overbearing customer offscreen. Clampett is able to satisfy his craving for wordplay on all fronts; whereas the menu in the back advertising a Sheridan Salad “with plenty of OOMPH” appeals to a more pop culture conscious attitude, a nod to Ann Sheridan who was known as the “Oomph Girl”, the customer’s “I want a GOOD hamburger, and I want it BAD!” is more subtle, practical, yet amusing all the same.

Despite never showing the customer’s face, his presence is still felt all the same. Daffy’s ever growing consciousness and awareness for the people and obstacles around him feed into the patron's intimidation. Even before the beefy fist is slammed onto the counter the first time, Daffy flinches, seemingly permanent grin fading as he is jarred by the overwhelming demeanor. The same happens with the second slam of a fist, presenting a duck who is visibly taken aback at the unnecessary aggression. Silhouettes and shadows projected on the wall seen to take a life of their own—fangs are visible when he talks, and, viewing the composition with a two dimensional mindset, it seems as though Daffy is backing away from the lurching of the shadow itself, physically reacting to an absence of light that is just as lifelike and demanding as the form it is being projected off of.

Daffy’s reactions to the customer are yet another solid indication of his consistent development. He recognizes threats and the gravity within rather than remaining completely oblivious, whether that oblivion comes from the throes of full insanity or is a means of rebellion and establishing himself as an authority figure (such as in Scalp Trouble or even The Daffy Doc.) The early Clampett Daffy craved authority as he grew more sentient. However, such a craving isn’t very present here, making him seem more down to earth as a result.

Still, this cartoon was produced in 1939, and the duck of 1939 remains loyal to his namesake. His visible surprise at the imposing authority of the customer is only temporary—a vacant, obedient grin is quick to slither back on to his face, as though representing a physical and mental shift back into gleeful hysteria.

Dialogue furthers such a change. A philosophy dutifully abided by since The Daffy Doc, Daffy launches into a circuitous, mush-mouthed, borderline incomprehensible slew of affirmations. His breathless “Comin’ right up! Yessiree! Comin’ right up right away! Yessir! Comin’ up! You said it, chum! Yessiree, comin’ up right away! Just a jiffy! I’ll have it for ya in just a jiffy!” indicates a restlessness that is almost compulsive.

Whereas most characters would sputter such repetitive replies in a moment of vulnerability, a symbol of overcompensated loyalty to the angry customer, this is just how Daffy talks. He’s already gotten over the initial surprise at his overbearing guest. Such repetitive syntax would be a character trait that stretches on for years and years after this short was released—it’s a fantastic depiction of boundless energy and other synonymous uninhibitions.

Likewise with the askew lip sync. While it isn’t as off kilter at this point as, say, certain scenes in The Daffy Doc where full lines of dialogue are spoken through a single open mouthed beak pose, it does nevertheless further the inherent disconnect and render Daffy all the more rambly and eccentric.

Much like the detail of the broken china in the trashcan, further background details underscoring Daffy’s excursion to the freezer allow the environments to feel more occupied, homely, and lived in. Whether that be a list of jobs tacked to the wall or comestibles like tomato soup cans and oatmeal cookies, the mission to achieve a believably occupied atmosphere is achieved.

The most intriguing detail of all, however, lies in the calendar. Tacked to the side of the freezer is a photograph of a calendar, a cute, wry detail that begs the question of its efficiency—does a new photograph have to be taken everyday to account for the changing date? Surely they couldn’t hang an actual calendar up? Instead of questioning the mechanics, we are intended to view the date: a very clear “13” is proudly emblazoned, a fitting omen for the events soon to transpire. Kudos to Clampett and company for the idea; it isn’t meant to be obvious in a way that is distracting and condescending. The storytelling remains the same regardless if the audience caught the detail or not. Instead, it offers an added incentive and ties the story together even tighter and rewards those who do catch it.

Bad omens are indeed realized as Daffy opens the freezer door in a purposefully tight yet immersive perspective shot to share his point of view. To further appease Clampett’s adoration of pop culture references, the wisdom of Jerry Colonna is expounded in a note from “The Mice”, borrowing his catchphrase of “Greetings gate!” to share the bad news: the hamburger meat is gone. Whether it be the musical crescendo reaching its triumphant climax, Daffy’s beak visibly gawking upon realization in the foreground, or the playful specificity and sophistication of the scenario that maybe would have been lost on a shot of a rat scurrying away with a piece of meat, a number of very purposeful elements allow the reveal to prosper.

Moreover, Daffy’s hysteric, dubious shriek of “THE MICE!?” indicates a sense of ironic familiarity. Even if he is repeating just what’s on the note, the mice indicates a long running battle—not some mice, not a mouse, the mice and all of the identity that comes with such a title. His outburst at such a revelation is a great incongruity to the quietude of the music and atmosphere to enable the audience in focusing on what the note says.

It is here where his mutterings are synonymous with The Daffy Doc (and Wise Quacks too), lip sync now thoroughly out the window. Daffy is a unique character in that he is able to own and pull it off well—perhaps a questionable choice on the surface level, it instead solidifies an incoherency that is unhinged yet devoted. Very synonymous with the ad-libbing system so beloved by Fleischer Studios, bestowing an endearing, offbeat grittiness to the characters and atmospheres rather than hindering them.

Porky’s Last Stand is a surprisingly tidy, cohesive, and solid cartoon with a keen awareness of balance. Docile moments are followed by eccentric ones, loud moments followed by peaceful quietude. While Porky’s incoming antics feel comparatively shoehorned and do soften the cartoon’s foundation just a tad, it is a logical counterbalance to the restless friction inherent to Daffy Duck and his scenes therein.

Even then, Porky’s spotlight is far from a dud—this cartoon runs at consistent highs, and it’s difficult to maintain at a constant. Instead, he serves as a vessel for Clampett and Foster to squeak their various restaurant-ing gags through. First order of business is the telltale bait-and-switch to get a laugh from the audience: “Ye-yessir! Yessir! Eh-a cuppa coffee and eht-teah-two ay-ay-eh—two ay-aey-eh-ehh… a couple a’ cackles!”

Next, a loose reprisal of a gag first seen in Tex Avery’s Milk and Money. Whereas Avery’s gag involved entire bottles of milk being dispensed from a spigot, here, it’s a steaming cup of coffee. No attempts are made to preserve the rigid physics of a porcelain coffee mug, and for the better—the almost sickly gelatinousness in which the mug is dispensed highlights its whimsicality and unconventionality. Likewise with the droplets of liquid that emanate from the impact. While it very much could be an error, coloring the droplets white instead of “brown” again scores the absurdity of it all, playfully teasing more questions on the physical properties of the mug.

Porky’s excursion to get some eggs is underscored by a somewhat odd solo of seemingly unpitched singing. If it is pitched up to the correct amount, then it wasn’t delivered in Blanc’s typical vocal register for Porky. Much like the opening, the off-kilter singing almost seems to contribute to the playful sincerity, a charm in its obnoxiousness. Regardless of whether that charm was accidental or purposeful, the overall impact is relatively the same. Such furthers the cute buffer provided by Porky to counterbalance Daffy’s hysteria.

On the topic of music, Stalling inserts a subtle piece of musical theming regarding the characters. Though still an accompaniment of “I’d Love to Take Orders From You”, the orchestrations that play in Porky’s scenes are comparatively muted, playful, a confident docility whereas the arrangements heard in Daffy’s scenes are more flighty, fragmented, brash and plucky. It provides a fantastic and attentive commentary on the differences in personality between the two characters—next to Daffy, Porky is a lot more controlled and relaxed, pleasant, whereas Daffy himself is hyper, unfocused, the staccato music beats providing a fitting jaunt.

Clampett’s filmmaking has been immersive on multiple fronts for this particular entry. Characters and personalities, settings, are one thing, but actual camera maneuvers and composition to further draw the audience in is another. Similar to the camera panning down and dissolving to the interior of the food stand, similar to the perspective shot of Daffy opening the freezer door, the camera now follows Porky as he opens the refrigerator; the truck-in isn’t long nor grandiose, but enough that makes it feel as though the audience is reaching inside the fridge with him. All through a simple zoom.

Reaching into the fridge takes us deeper than we are led to think—Clampettian sensibility prevails as the camera cuts to the outside of the wagon, where Porky reaches through a cubbyhole to lift a hen off her nest and grab the eggs from beneath. A politely amusing subversion, it benefits from matter of fact, unobtrusive delivery, and economy in clarity is a great plus; particularly with Porky being able to fit his head in the cubbyhole just right. Some of the motion appears awkward, primarily the moving cel overlay of his hand grabbing the eggs juxtaposed against total stagnation otherwise, feeling somewhat unnatural and too even, but that’s being particular.

Similar critiques could be given for Porky’s remaining walk cycles. Particularly on a shot where he approaches the frying pan, each cel is held for one frame and don’t feel anchored in its weight, making it seem as though he glides across the screen. Generally unnecessary head turns do little solidify the motion.

As such, John Carey’s closeup of Porky cracking the eggs against the skillet comes as a great relief. Solid form in the fingers, delicate timing with the wrist flicks and easing of yolk into the pan; each tap of the egg pans out with the musical accompaniment in time, tiny violin plucks giving an added jaunt to the cracking.

Purposefulness and fragility in the animation isn’t all for show—rather, it introduces an antithesis to further exaggerate the shock of a fully formed baby chick hatching out of the second egg and hopping frantically on the burning surface. As always, a great array of combined elements work together to further the gag’s success: that the egg still leaks an unmistakable yolk before hitting the pan further jolts the audience much more than the alternative of the chick tumbling out by itself, the seemingly unnecessary camera truck-in on the chick put that jerking, surprise feeling into motion as well as clarify the antics of the chick, and while the little lightning effects are pure artistic trademark, they add a certain graphically minded flair that benefits the whimsy as a whole.

And, of course, Mel Blanc’s voice acting. Shrill “Ow!”s and “Oh my goodness!”s pepper the screen as the poor poultry scrambles around helplessly on the pan—a consistent flute trill from Stalling in the orchestration and wonderfully appealing, logical, and fluid drawings from John Carey do great favors in scoring the pipsqueak monologuing.

“HEY! WHADDAYA TRYIN’ TO DO? GIMME A HOT FOOT!?” The outburst has Clampett’s name all over it. That the chick eyes the audience rather than, say, Porky, makes the breach of decorum seem all the more abrupt and surprising. It would make sense for him to chastise Porky, but to yell into the audience births a certain self awareness that is endearing more than not.

Thus enters the curse of John Carey, which has been touched on in previous reviews—he sets such a high precedent of quality with the solidity in his drawings and awareness of how weight and timing impact the motion that the scenes followed by another animator seem much more weak and lackluster in comparison. Nothing egregious by any means, but certain notes; the motion of the chick hopping off the frying pan handle could use more elasticity and weight, the run into and through the kitchen could stand to be faster, and the chick burrowing under its mama suffers from static movement on the mother’s part and weightlessness of her feathers covering her brood.

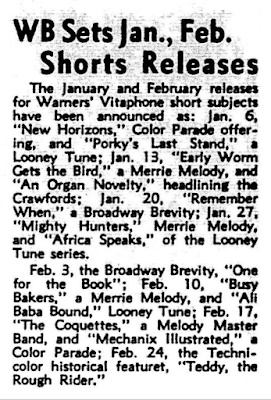

With that said, the intent is clear and the energy is still very much palpable. The chick slapping a “DO NOT DISTURB!” sign on its mother—who seems to welcome the free advertising warmly—immediately distracts from any animated shortcomings and provides a cute footnote. Often, such critiques come from an understanding of not that the motion or animation itself is bad, but it has potential to be stronger and comes as a slight disappointment when that criteria isn’t met.

Dutiful obligation to the cartoon’s formula of balance is made through a return to the much more high strung and less docile Daffy. Complete absence of a lip sync, circuitous, aimless dialogue (a thrilling monologue of “Hamburger, hamburger, I gotta find it… hamburger, hamburger, I gotta get some hamburger someplace, now lemme see, what’ll I do to get some hamburger…”) and equally aimless pacing around all amalgamate to reach the pinnacle of Daffy’s insane mutterings. Comparatively crude yet simplistic animation benefits the reigning eccentricity, unbalance, all furthered through little gestures to convey brain wracking peril.

Perhaps the best of these gestures is Daffy’s incredibly brief and halfhearted search under a bowl of batter, as though a stack of hamburger meat would just so happen to be at his disposal. Even better is the dubious shrug towards the audience, as though he can’t possibly fathom how a thorough search such as that one could ever fail.

Awareness and interaction with the audience is a key component of Daffy’s being and one of the strongest arguments for his appeal and charisma. He is a very vicarious character who wears his thoughts—or lack thereof—and emotions on his sleeve, never one to keep motives quiet, good or bad. A certain knack is possessed in that he can break the boundary line between screen and audience at any time and never have it feel self aggrandizing or like a major production—whereas a majority of these fourth wall breaks have a tendency to (rightfully) call attention to themselves, awareness of the audience completely unmistakable, Daffy’s awareness is more subtle, innate, just a facet of his personality more than a theatrical device.

In any case, the solution to his plight is offered through the means of commendably clear staging. A glance out the window reveals a cow in the distance grazing on some grass—Daffy’s “Weeeeell!” indicates that won’t be the case for long.

Clampett’s penchant for sadism reaches yet another zenith in the remaining half of the cartoon. While slaughtering a cow in cold blood to appease a demanding customer is violent enough in itself, an eye for pathos in the environments and situation itself allow the wound to sting even further. Indeed, metaphorically burning lacerations are delivered upon the realization that this is a calf, not even a fully grown cow. Framing the staging with wildflowers establishes a rueful, sardonic tranquility, a simultaneous appropriation of and middle finger to Disney.

And, of course, that we view the calf from Daffy’s point of view, resulting in a cross dissolve to the image of a steaming hot hamburger. Clampett and Foster make no attempt on any sort of commentary regarding the calf’s size—no “kiddie meal” sign attached or a little slider aberration rather than a full on hamburger. No, as mentioned before, Daffy is a highly immersive character, and we are meant to view this from his own point of view and his thought process. In his eyes, food is food, no matter how big or small, no matter how docile or innocent. All of this is conveyed through his shrill, apt narration: “Looky looky looky!”

Therefore, another song number is in order. Not one orchestrated by an invisible, ethereal chorus of tinkly, high pitched voices cooing from the void, not one meant to evoke Disneyesque jolliness and joy—if anything, it’s an anthem. An anthem of impending victory for Daffy, an impending loss for the calf.

The number is an appropriation on a number of fronts, but by no means disavows its excellence. Mainly, it’s an appropriation of “With Plenty of Money and You”, dubbed by Daffy as “With Plenty of Gravy on You”, which is where the second piece of inspiration strikes—a conniving weasel sang the same appropriation in Friz Freleng’s Plenty of Money and You in 1937. Here, however, the song almost feels much more natural, fitting, indicative of Daffy’s motives, but that may very well be considering it hardly has any real lyrics and is half cathartic gibberish.

Gleeful “HOO HOO!”s are liberally interspersed, serving as a chorus in their own right. Effeminate hip shakes and eyelash flutterings bestow a cruel coyness on an already delightfully warped situation. There are no tears to be shed here, no angels lingering on a shoulder, and certainly no sign of restraint—he actively revels in the thought of slaying a calf. The tunnel vision has set in; once Daffy has a motive, it’s impossible to steer him off track.

Likewise, the unmistakably nefarious grin flashing on his face as he reaches for a mallet indicate a haunting awareness and concession. Much of the next minute or so parallel scenes in The Daffy Doc. Daffy stalking Porky with a mallet to knock him unconscious and perform involuntary surgery followed a line of logic—absolutely warped logic, but a somewhat coherent one from the lens of Daffy—but he still was very much completely out of his mind and oblivious to the repercussions that could follow. In spite of all of his violence, there was a lingering sense that he was just trying to assert himself and—in his mind—do good.

The grimace flashing on his face here completely throws every notion of good intentions out the window. It is a concession to his iniquity, awareness—he absolutely realizes that he is going to cut the life of a calf short and actively revels in the opportunity of finding a solution to his problems. He understands it’s a gruesome one and embraces the thrill that follows. Lyrics of “Oh baby, what I’m gonna with you…” reveal a consciousness and awareness that actively render the scenario all the more disturbing just as it is hilarious.

Even with all of this in mind, Clampett continues to tease the audience through background details. A butcher’s knife and hacksaw are very clearly hung on the wall nearby, all instruments that are inarguably much more gruesome and economical in getting the job done; that Daffy reaches for the comparatively much less horrifying mallet almost seems to be a tease in itself, poking fun at the viewer for ever assuming he might go for the tools actually equipped for the kill. Predictability is not in Daffy’s nature.

A side eye to the audience as Daffy exits the food stand continues to uphold the audience awareness so stressed prior. He understands he has a following, and the glance almost reads as validation seeking, an “Are you seeing this?” that solidifies he’s aware of the self imposed spectacle. There are absolutely no doubts to his awareness and consciousness. Unlike The Daffy Doc, his acts cannot be pardoned under the guise of obliviousness. Pure impulse, yes, but attempts to make his self awareness exceedingly clear bestow a gravity that is truly unparalleled.

So much of this sequence has its DNA rooted in The Daffy Doc, which reaches its most obvious point in the shot of Daffy actually stalking the calf with the mallet, used verbatim from the aforementioned cartoon. Typical Clampettian animation reuse, but considering the similarities in tone and setup established prior, the recycling is somewhat fitting.

Likewise, various maneuvers from the direction itself decorate the sequence beyond transparent cribbing. The camera focusing on a shot of the calf prancing before trucking out to reveal Daffy enables the audience to get further attached to the poor, docile creature, a concession from the filmmakers this time at the cruelty of the scenario. Moreover, Daffy’s ongoing singing abiding the Doppler effect introduces an impending threat, a threat getting louder and closer with each jolly footstep.

Same with his voice getting quieter as he follows the calf into the barn, side eyes to the audience still rife. With nonstop singing, gibberish, and HOO HOO!ing, the crescendo of the music and brief silence that follows once both are in the sanctity of the barn is genuinely unsettling.

However, knowing Daffy, silence is never too prolonged in his presence. Lingering feelings of an emerging threat are revived once again as his voice slowly gets louder, marking his return. The shrillness of his voice remains—if not amped up further—as he coos at the “calfy”. Again, another indication that he is very aware of the bovine’s vulnerability.

His variations on the soft “C’mon out now, c’mon!”s are met with some resistance—he has to physically tug on the poor calf’s tail to even drag him back outside. The sheer, dripping disingenuousness in his “Why, this is gonna hurt me worse than it does you!” carried in such a cavity inducing coo is absolutely genius on the part of Blanc’s acting and Clampett’s vocal direction. It reeks of total duplicity, sadism—it’s a total lie, and Daffy knows it just as well as the audience knows it.

And a lie it is, for what does Daffy drag out from the depths of a barn but a giant, hulking bull. Again, acute attention to detail and meticulous staging make the reveal all the more rewarding. Attention to detail boils down to the patterning on the tail—the calf’s tail was white, whereas the bull’s is all black. A certain dependence on the audience not exactly catching such a small change is necessary for the actual surprise; there shouldn’t be too much build up to give away the reveal, but a minute detail such as that allow the audience to reminisce and realize the signs were inevitably there.

Introduction of the bull follows a similar logic. The bull turns around to face Daffy, but the perspective is shot with his face away from the camera—vestiges of suspense linger as the audience isn’t granted a proper look at the bull’s face until absolutely necessary. Which, again, makes for an all the more satisfying reveal.

“Mmmmmmmooooohhh YYYYYEEEEAHHH?” Blanc’s voice for the bull is perfectly directed, his gravelly slurring portraying exactly how a bull would sound if it could talk. Not too human nor concise, though—a comparative lack of anthropomorphism is necessary in maintaining a bigger threat and discrepancy between himself and the much more anthropomorphic Daffy. A bull walking on two legs and speaking in complete sentences and being a bully is certainly funny, but the certifiably animalistic behaviors here bestow a greater sense of unpredictability, antithesis, a stronger threat as a whole.

It takes the bull’s rebuttal of Daffy’s coos for him to even open his eyes and recognize the mistake. How it even happened, we don’t know—a raging bull looks much different visually than a baby calf. However, that’s not important, and getting too caught up in the details lessens the severity and fun. It’s the reactions that matter most, the scenario more than the specifics, and the storytelling itself still maintains great clarity.

Further advancements in Daffy’s evolution are made through a close-up—the detailed shot of him gulping and sweating as creeping realization kicks in bestows a vulnerability and, there’s that word, awareness we haven’t been privy to prior. Outside of mildly concerned and/or vacant glances towards the camera in cartoons such as The Daffy Doc, Scalp Trouble, Wise Quacks, etc., the gravity of the perilous situations so inherent to his being have never once dawned on him in the way it does here. Wise Quacks gets close with an “Uh oh,” before running away from a flock of murderous vultures, but the raw tension and everything halting at once just to show his reactions unfold in real-time has never been a privilege yet.

Same with the guilty grin slithering on his face in the following scene, animated by John Carey. Similar beats of sheepish grins have been touted briefly in shorts before (as we just saw in The Curious Puppy), but never to this degree of pure caricature nor exaggeration. It precedes a very similar take in The Wise Quacking Duck, directed by Clampett a mere three years later—even then, this example feels far more streamlined, two dimensional, purposefully and joyously unnatural. Stalling’s equally slimy violin slide to accompany the gesture brings further notice to the action and allows it to flourish.

Polite pats on the bull’s head are completely futile, nothing but a transparent attempt to save face, and Daffy knows this completely. His deceptive gregariousness immediately crumbles once the bull snorts and shakes its head—he’s met with a quick, cowardly retreat. Carey’s solid animation timing and need for speed benefits the transformation between façades greatly, as they are only barricaded by a mere smear frame. Which, in turn, allows the retreat to read as even more fast, snappy, reflexive. Still, refreshingly and surprisingly aware of his image for a change, Daffy makes yet another transparent attempt to act pleasant by patting his sides and slathering on another phony grimace.

Auditory ambience, as it always does, helps greatly in portraying the threat of the bull. Quietude in the music score is topped with an ominous, low, thundering drumroll to help materialize the suspense, and metallic, knife scraping sound effects from Treg Brown when the bull’s horns scratch together like knives perfectly further the metaphor and believability of the threat. That the bull is in constant motion during the close-up, consistently heaving angry breaths, makes him feel much more alive, realized, not something to mess around with. All applies to the intimacy of a straight on close-up from Daffy’s point of view.

Graphic sensibilities that pepper the early Clampett’s work have been expounded upon in further reviews, but they are always worth mentioning; especially here. Daffy tugging on his collar to extend his neck and gulp—quite audibly at that—feels like it came straight from a newspaper comic and was transcribed faithfully into animation. The clear staging, the streamlining of Carey’s animation, the comical grandiosity of the gulp, the “Ulp,” sounding like it came straight it’s native habitat of a word balloon poised above Daffy’s head. Such an influence allowed Clampett to revel in the world of his cartoons and strike any and all opportunities to remind his audience of the medium rather than trying to chase the Disney philosophy, the illusion of life, or anything of the sort. Such a comparatively “manufactured” atmosphere benefits greatly from the equally unnatural gestures from Daffy.

Great distortions on Daffy’s legs follow the same principle to an even more grandiose extent. Ironically, the maneuver of him sticking his leg out across the screen as a means to slink away “unassumingly” is both ahead of its time and retroactive; it precedes the great, gelatinous distortions of his legs in the climax of Clampett’s Baby Bottleneck, one of his absolutely most inspired sequences as a filmmaker, but it also provides a fitting tribute to the early rubber hose era where distortions such as these were commonplace in (keeping it Warner relevant) a Bosko cartoon.

Of course, all of this sly, thick, conscious tension serves as a mere stepping stone to the true object of Clampett’s affections: the hysteria. While a bit difficult to perceive due to very subtle impact lines and a lack of sound accompaniment, Daffy’s manic twirling as he retracts his foot isn’t entirely voluntary. Rather, it’s his foot smacking into his body that spurs the rotations—all of the self awareness and restraint on Daffy’s part are metaphorically jarred loose from the impact.

Carey’s double exposed multiples and smears evoke the earlier Clampett who used multiples as an excuse to slip character and crew cameos in by any means. While no such appearances are given here, the energy is synonymous to that period, a period where Clampett and company were consistently operating at a high threshold of energy and quality; something that has since softened within the past year.

Likewise with the signature Stan Laurel hops and whooping; whereas Daffy’s intermittent “HOO HOO!”s in his song number felt more decorational, polite in their glee, his shrieking here is unadulterated catharsis. The fuse has been lit, pleasant façades are bygone. Instead, the thrill of the entire scenario is intoxicating, and one Daffy himself feeds into through the inherent contagion of his hysterics. For a few split seconds, he seems delighted in the prospects of a chase.

That, predictably, is only momentary. In the adjoining sequence of the chase, also animated by Carey, Daffy turns from gleefully crazed to bombastically confrontational as he spitballs a number of threats to the bull. Compelling arguments such as “Why—you—I—!” are fueled by pure emotion and stubbornness rather than any sort of logic—you can only tell a bull you’ll crush them like a grape for so long. That Daffy continues to sputter indicates a need for authority, similar to the duck seen in The Daffy Doc and Scalp Trouble; to stop arguing would indicate a loss of dominion, bravado, even if there is nothing else to say.

Clampettian philosophy of asynchronous lip syncing greatly benefit the freneticism, impulsivity and screwiness now more than ever. Despite the animation being shot on ones, movements are still very clear and comprehensive when they need to be. Inherent choppiness is somewhat necessary for the energy this sequence demands to disorient the viewer, but the motion is never more muddled than it needs to be. Background paintings play a great part in furthering such a momentum as well; the entire pan depicts trees and the encompassing environments as nothing but a pure streak, brushstrokes angled to manufacture a fake motion blur that looks great in motion. Fleischer Studios was prone to such a technique in their own cartoons as well.

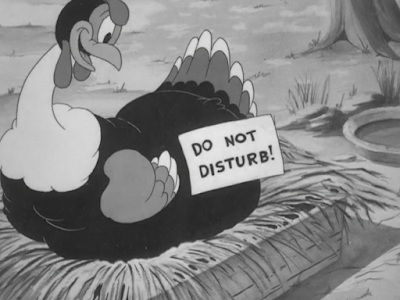

With so much of the cartoon built on the foundation of contrast, contrast, contrast, Daffy seeking refuge in the food stand is a perfect antithesis to the false bravado exuded just seconds prior. His smack-talking, finger wagging façade is immediately replaced by inarticulate, strangled cowardice that he feels acceptable to show only when not confronted by a threat. In this instance, Porky is about as far divorced from a threat that one can get.

Benefits of Carey’s handiwork being concentrated through this section of the cartoon allow palpable acting differences between the fervent, desperate strangled gurgling and gesturing from Daffy and the naïve, unintentionally condescension of Porky listening attentively. Juxtaposition could not be starker between the two; even if Daffy is genuinely incomprehensible, the wide eyed expressions, frantic finger pointing and generally terrified disposition are strong enough at indicating a problem.

Which is why Porky’s politely inquisitive “Someone to see me?” is so funny as it is inadvertently insulting. It isn’t at all an act of ill will, as he shows clear interest in Daffy’s rambling—he is just so painstakingly oblivious that it reads as dismissive and unintentionally condescending.

Likewise with his own explanation of “Eh-pp-peah-peh-probably a salesman,” as though Daffy’s reaction is justifiable towards the perils of door-to-door salesmen. He makes no attempts to clarify, doesn’t ask Daffy to slow down or repeat himself—he just accepts what Daffy says at face value and trusts him enough to have some sort of ulterior motive. A much more endearing and amusing commentary on his character than going the logical route of interrogation. On the other side of the coin, Daffy merely throws his hands over his head and cowers rather than trying to clarify himself or make an attempt to reason. He knows they’re dead meat anyway.

Clampett’s filmmaking and Foster’s storytelling make a very brief argument for Porky’s case: following a climactic, suspenseful crescendo of “All In Favor Say Aye”, the music comes to a brief halt when there’s nobody at the door. For a moment, Porky stares back again at Daffy, as if suddenly realizing there must be a reason behind his histrionics and maybe this is no salesman after all. Opening the door to nothing but an empty field does not bode well for Daffy’s argument.

A bull veering out of the corner and raging straight towards the door, however, does. Once again, major kudos to concise staging; Porky, Daffy, and the bull are all easily visible, no one character dominating unless absolutely necessary—such as the bull making his entrance.

Having the bull charge straight towards the camera bestows a vulnerability upon the audience, as though Porky slamming the door shut isn’t only to protect himself and Daffy, but to shield the audience as well who are in the direct trajectory. For a split frame, Porky’s eye direction points towards the camera rather than at the ground when he closes the door, as though acknowledging our own presence.

Refinements to a very similar sequence in Pied Piper Porky are made upon the bull’s recovery outside. Like the aforementioned cartoon, the bull shuffles along while humming inconspicuously, hands behind his back—the amount of humming juxtaposed with the subsequent catharsis of energy that follows reaches a much more solid, less grating balance that doesn’t hinder the overall transformation. Briefly enabling the bull to act more anthropomorphic, standing on his legs and walking like a human person, further provides yet another antithesis that allows his four legged scramble to feel more jarring, more sudden, more clear and more energetic.

Thus, the true climax begins. Elasticity in the bull charging straight through the food stand and out the other side harken back to the early Clampett once again, reminiscent of the days where it seemed every single environment or structure was founded with plasticity in mind. That the chickens (and eggs) are still perched on the roof of the wagon is amusing in itself, as is Porky visible from the inside. His exit on the other side of the wagon, bull close in tow is more comprehensible as a result, but also provides a slight, added pathos seeing that he is in the direct path of trajectory and has no idea what’s coming.

For the sake of clarity, Porky has since deserted his chef’s garb—too many little pieces of fabric to track at such high speeds. Considering his uniform is still visible in the previous scene when he exits the stand it is a bit of a continuity error, but not worth throwing a fit over. Bull chases are more important.

Much of the chase—like the remainder of the cartoon—promotes a strong balance that prevent it from growing too monotonous. A shot of Porky and the bull running horizontally is followed by a straight on perspective shot of Porky zigzagging across the screen and leaping onto a tree branch. Even that in itself, the bull charged straight at the audience in a divergence of direction which keeps it even more visually appealing. Likewise with Porky doing a full rotation swinging onto the branch. A smooth, rhythmic momentum that rides the waves of the music and the atmosphere.

Another horizontal shot follows to splice the patterns some more, this time with some incredibly tactile and seamless animation of the bull turning around and charging the opposite way. Backgrounds are simple in the horizontal shots especially, but that is by design; the viewer’s eye is naturally drawn to observe the acting and movement first and foremost, uninhibited by any flashy or obtrusive background details.

A heart take in its fledgling stages is granted upon a close-up of a profusely sweating Porky. Easy to take for granted now, the take is certainly a novelty in that it remains one of the first in the studio, beaten only by Tex Avery with Dangerous Dan McFoo. Yet another sequence that looks like it was adapted straight from an inked drawing, Porky is drawn particularly appealing through tall eyes, pinched snout and mouth, round body, round head, squat feet and so forth. Fittingly streamlined and perhaps even exaggerated, but not to a degree that is overly apparent.

Whether it was a cost cutting measure or a pure stroke of filmmaking genius (likely both), that one option doesn’t part particularly outweigh the other renders the next sequence a success. In a maneuver that evokes comparisons to the sort of utter caricature and speed seen in Frank Tashlin’s cartoons, the next scene of Porky disembarking from the tree branch is the exact same as the first sequence, only played in reverse with slightly fasted speed. Likewise with the flipped shot of the bull charging after him. It provides a certain wry summary of the scene—Porky’s getting chased by a bull, we know—but is incredibly self aware and embraces the shortcut. That it manages to save a few bucks and effort is a bonus.

An abundance of scenes involving Porky typically indicates it’s time for Daffy to step up. Indeed, the sputtering, incoherent, panic-stricken duck from not even a minute ago is now all smiles, waving a gray red cape and taunting the bull with a boisterous “HEY, FERDINAND!” Daffy in particular is a character whose references to pop culture are more innate and feel natural to the character, another consistent trait, so the shoutout to Disney’s Ferdinand the Bull is a welcome one.

More importantly, Daffy’s sudden mood change is a great commentary on his cowardice and bravado—he’s quick to return to threats and taunts when he knows he’s out of harm’s way, acting as though nothing had happened before. In fact, his teasing is borderline childish as he spreads his bill/cheeks apart to waggle his tongue in yet another very two dimensional and caricatured pose. Even though he’s explicitly taunting the bull to target him, the threats themselves are executed with a mindset that the bull won’t act.

So, when the bull does, exceedingly making a case that he’s not the impressionable dope Daffy mistakes him to be, that’s when shrieking, craven histrionics resume. In Daffy’s defense, there’s a lot to shriek about—knowing the climax is reaching its zenith, Clampett and Foster pull out all the stops by not only having the bull turn into a literal bull-et, propelling himself at gloriously impossible speeds, he uses the sides of the screen to launch off of. Excessive wrinkles and squashed construction on the bull as he presses himself against the imaginary boundary reassure the audience that this is no mistake.

Cowardice does not only have an effect on Daffy, but puts the livelihoods of others in danger. Once Daffy takes off, it’s revealed that Porky was cowering behind the cape, depending on Daffy to keep them out of danger. A naïve but grave mistake, and a nod towards the impulsiveness, cowardice and selfishness that would become some of Daffy’s defining traits.

Still, Porky—through a delayed reaction take, a Clampett favorite for the character—manages to solve his own issues by digging a hole in the ground and hiding from there. Seemingly specific as the circumstances may be in this case, the animation would be reused in The Timid Toreador under somewhat synonymous conditions. Innocent blinks from Porky to the audience reaffirm sympathy and sincerity—while already fantastic as is, the sequence is even funnier knowing he has no proper context as to how the bull got provoked in the first place or why it’s even there. His blinks seem to convey this itself.

Signature Clampettian foreground overlays parting as the camera trucks in are utilized less as a means of showing off and more as a way to subject the audience to the bull’s point of view. That is, the sheer force of his kick off the screen was so strong that it’s rendered him uncontrollable, flying right back to the food stand itself.

Whereas that may not be as much of a problem in itself, it does pose a problem for the poultry on top. They weren’t a mere decoration at all, but a rather elaborate punchline, camping out the entirety of the cartoon just for this moment. Stalling’s orchestration reaches a positively beautiful, grandiose, climactic finale as the camera delegates one brief shot to the chickens clutching each other and reacting in surprise. Pathos is necessary to allow impending impacts to land all the stronger. Repeated cutting back to the bull further reminds the audience of what’s at stake to begin with, as well as making the filmmaking feel more frenetic and thusly the scenario itself.

A collision is inevitable, and one that is very rewarding. Further reminders of newspaper comic influences are at their most realized yet with the “BAM!” that erupts after the impact and melts into the surrounding dust cloud. Another precursor to synonymously unapologetic typography in Baby Bottleneck.

Despite the commotion and violence, skillfully concealed by dust clouds to leave some of the impending outcome to the imagination of the audience and furthered through constant, clamoring sound effects of utter destruction, the end result is nearly not as gruesome nor sad nor mean spirited as one may think.

In fact, it’s a happy one—a wagon wheel left spinning in the impact is momentarily transformed into a merry go round, little chicks riding on their patient mothers as though they were the ride themselves. Stalling’s fairground accompaniment of “Start the Day Right” provides a solid bookend that is just as reflected on the screen itself; we start and end with the chickens on a musical note.

Even the dazed bull serves a purpose: in an era where most merry-go-rounds offered brass rings as an exchangeable prize, his own nose ring contributed to the joy of the little chicks as they grab for the dispensable goods. With that, we iris out.

If it maybe wasn’t obvious by the sheer length and tangentiality of this review alone, Porky’s Last Stand is easily one of my favorite cartoons of all time and in my top 10 favorite shorts produced by Warner Bros. Daffy and Porky team-ups tend to be in my favorites as is, but even outside of personal bias, this is an incredibly strong and confident cartoon that is anomalous for its time period and also one of the last of its kind. Much of the cartoon feels retroactive, nostalgic, a nod to the early Clampett just as much as it feels startlingly ahead of its time. Outside of a few exceptions such as, say, Prehistoric Porky or The Henpecked Duck, Clampett wouldn’t hit highs this tangible and at such a consistent rate all through the cartoon until he inherited Tex Avery’s unit.

Clampett isn’t an incoherent director, but he has a tendency to wear his dedication on his sleeve—much like his characters. It becomes very easy to discern whether he was interested in a premise versus where he wasn’t, when he gives a joke or story beat more attention than another. As such, his shorts—especially at this time in a time of creeping burnout—fluctuate with highs and lows. Last Stand is an exception in that, outside of certain parts in the middle section with Porky serving the customers (which is still full of fantastic gags like the coffee cup, the chick from the yolk), it operates at a consistent high. Having Warren Foster as a writer likely helped—the Clampett cartoons sans story credit, implying he wrote them himself, have a tendency to be very hit or miss, great or disappointing. Consistency is a great theme for this cartoon’s quality.

Balance is pivotal to the short, in that a high is often followed by a low, loud with quiet, pleasant with hysterical, and so forth. While that sounds repetitive on paper, Clampett and company manage to establish a rhythm that is coherent, smooth, guides the viewer along but the goods of the short itself remain engaging, subversive, unpredictable, funny. Allowing a hysterical, shrieking Daffy to follow a sequence with a much calmer, more oblivious Porky enables Daffy to feel more frenetic as a result.

Another major success of the cartoon stems from its awareness and integration of the audience. Some examples are more subtle than others and up to interpretation (such as Porky slamming the door on the bull charging straight towards the camera, as if attempting to shield the audience along with himself), but whether it be a side-eye from Daffy, a blink from Porky, or a scream from a chick on a frying pan, each element does its job in drawing the audience and making the viewer feel as though they’re experiencing the events of the cartoon vicariously through the characters. Even the staging promotes this—point of view shots from Daffy especially, such as opening the hamburger freezer door in perspective, having the bull stare straight at the camera while sharpening his horns, and so on and so forth. Action on screen is engaging just as it is inviting.

A charismatic cast of characters does great wonders for this as well. In spite of its title, this very much is Daffy's cartoon—but, even with this in mind, Porky doesn’t nearly feel as shoehorned as he could and has plenty of moments to shine, the opening and climax scenes especially. Still, this cartoon is incredibly vital in Daffy’s development as a character. While the crossed eyes, incoherent mutterings and certain skewing of logic all remind us that he’s still enraptured in his insanity, he is also self aware, vulnerable, and even presented in a light that is more sympathetic and perhaps even relatable rather than an object to be laughed at on the surface.

He exudes impulsiveness, cowardice, selfishness just as much as he does charm and charisma—all defining traits to last for decades to come. While they may be conveyed through a more fractured, crude, fledgling delivery here, they are absolutely earmarks that are present and have ample room to grow. This short is a great stepping stone with that in mind.

Speaking for myself, this absolutely is a comfort cartoon. The raw hyperactivity and energy exuded at such a consistent rhythm is intoxicating, but the cartoon possesses a great sincerity that makes it all the more warm and endearing, too. Sincerity primarily shed by Porky, such as his solo in the opening number or sheer, condescendingly innocent oblivion at Daffy’s garbled warnings of the incoming bull.

As mentioned in previous reviews, I’ve said that some of my favorite cartoons of this era are the ones that are able to blend genuineness and warm earnest with wry, snappy humor, both elements working together for the betterment of the short rather than trying to compete or beat down the other.

I truly think Porky’s Last Stand is one of the absolute greatest examples at reaching such a harmony; the sincerity and sweetness doesn’t talk down the viewer, and the more sardonic, witty moments aren’t acerbic nor punishing towards the characters. I also think it is truly definitive of the greatness that is early Clampett; so many aspects of this cartoon seem to call back to previous shorts of his through the unapologetic elasticity in animation, consistent hyperactivity, prioritization of stylized, graphic drawing, but all with the benefit of a comparatively more experienced director and crew.

I cannot recommend this cartoon enough, nor can I stress the true amount of adoration I hold for it. There are plenty of cartoons leading up to this point that I am incredibly passionate about, but I do believe this is the first cartoon we’ve reached that is a true, unmistakable favorite.

While the animation may be crude at times, that sort of grittiness works as an active favor, especially in scenes involving Daffy where he’s meant to seem, look, and act off kilter. It is an unabashedly joyous and inspired cartoon that possesses every single earmark of what I love about this time period.

Carl Stalling’s music—especially the opening song number and climactic music sting when the bull crashes into the stand—gives me goosebumps. Treg Brown’s sound effects are masterful in guiding the audience through the actions and hinting at what’s next. Mel Blanc’s voice acting needs no introduction, but it is inspired, enthusiastic, and visceral on all fronts. I adore the way both Daffy and Porky behave in this cartoon, and Porky especially is a character who I often use this cartoon as a reference when making an argument for the appeal of his polite obliviousness. Clampett genuinely seems to be enjoying himself through much of the cartoon, and that mischief, that playfulness, that adoration of cartooning that hasn’t truly been as tangible since the late 1938 cartoons all make a rightful and palpable reappearance.

It’s a cartoon that tends to fly under the radar when discussing Clampett’s work, but is a short that I can honestly say I’ve never heard a bad thing about. For good reason, too. I truly feel it is wholly representative of the joys of not only Clampett in his early years, but the earlier, more youthful Warner Bros as a whole beginning to find its voice. This is a very formative cartoon that shows its influence in terms of both characterization and filmmaking. As the first cartoon of a new year and a new decade, it bodes for an incredibly promising start.

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment