Release Date: March 2nd, 1940

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Chuck Jones

Story: Rich Hogan

Animation: Bob McKimson

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Arthur Q. Bryan (Elmer), Mel Blanc (Bugs), Marion Darlington (Bird)

(You may view the short here or on HBO Max!)

March 2nd is a date that holds quite a bit of weight for Warner Bros and its history. 1935, it marked the debut of Porky, who would quickly rise through the ranks from a member of an ensemble to the studio’s first long lasting flagship character. 5 years later in 1940, it marked the debut of Elmer. The real one.

Not unlike the development of a prototype Bugs Bunny to the real thing, Elmer was a pre-existing character who was completely removed from the refinements that would be made by a director different from his initial creator. Tex Avery’s Elmer capitalized on his enigmatic absurdity, introduced first as a character serving only to disrupt the action by nonchalantly strutting across the screen—much to the chagrin of his co-stars. As we have explored, he dominated a number of Avery’s cartoons before Avery inevitably evolved past the desire to feature him. Even in the last handful of Avery directed proto-Fudd shorts, he had begun to receive a handful of small tweaks in redesign; his eyes began to open, his nose more constructed rather than a bulbous blob.

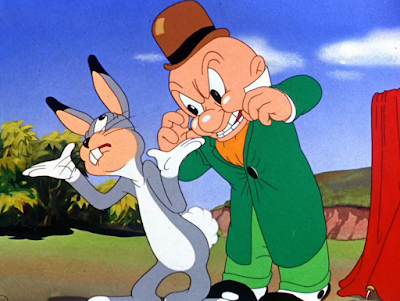

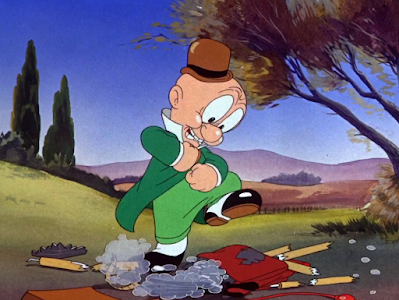

Jones’ take on the Fudd is much more sophisticated in comparison. Though still sporting the same green clothes and derby, traceable in his origins through bulbous construction, he is now taller, more sculpted, eyes open all the way, proportions more even; he appears much more human than the comparatively alien prototype touted by Avery. That, and his voice has finalized—the biggest indication of a change lies in Arthur Q. Bryan supplying his vocals for the character.

Mentioned in previous reviews, Bryan was hired by Schlesinger because he performed that distinctive voice on radio shows and in comedy clubs. It was a pre-existing shtick—Elmer just so happened to be the vessel to manifest it into. Indeed, this cartoon (and a number of early Elmer shorts) are heavier on the dialogue side, likely in an attempt to acquaint the audience with such prestigious casting. Audiences in 1940 knew very well who Bryan was; this novelty of a character being specifically tailored to his shtick certainly wouldn’t go unnoticed.

While it would be Tex Avery to provide further tweaks to Elmer’s design that are more comparable to his appearance now—larger cranium, more uneven proportions, more squat body, smaller eyes—Friz Freleng would adopt Jones’ design for his Confederate Honey and The Hardship of Miles Standish, a sign that this character was meant to stay. Elmer’s Candid Camera isn’t just a spitball of an idea from Jones. That other, unrelated directors were adopting the same design and mannerisms and character as a whole indicated a growing, collective adoption of an idea.

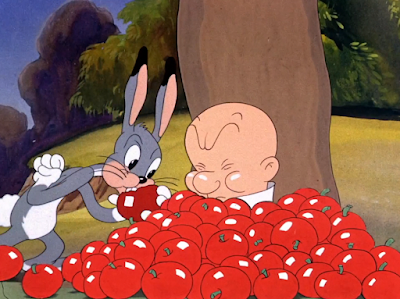

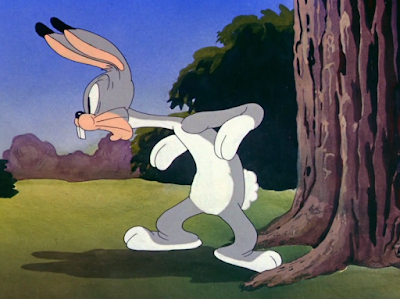

Worth mentioning is the appearance of the proto-Bugs in this cartoon as well. Following the design sensibilities of Charlie Thorson from his redesign in Hare-um Scare-um, the rabbit receives more design tweaks, but only slight. His once yellow gloves are now replaced with white paws, his nose momentarily black instead of pink, and his ears have black tips—interestingly, the tipped ears can still be seen on certain layouts and animation drawings with the fully redesigned character, as well as on certain comic book covers. The prototype bunny’s personality receives a bigger overhaul than his design, but more on that later.

A cartoon Chuck Jones freely expressed his disdain for in later years, Elmer’s Candid Camera isn’t as nearly far removed from the dynamic established in A Wild Hare. If anything, Hare springboards off of certain ideas teased here. With a newfound passion for photography, Elmer’s attempts to take snapshots of the wildlife are quickly dashed through a certain disruptive, contrarian rabbit.Our view of the newly redesigned Fudd is obscured firstly through a close-up painting to establish the scene. A book emblazoned with the bold typeface of “HOW TO PHOTOGRAPH WILDLIFE” acquaints the audience with the indisputable presence—while the same effect could be had by jumping directly to the shot of Elmer reading the book (as well as quicken and streamline the pace), the close-up admittedly distributes more weight on the subject matter and ensures the audience knows exactly what they’re getting into.

As mentioned in the introduction, this cartoon places a heavier emphasis on the gimmick that is Elmer’s voice. Or, more accurately, the novelty of Bryan filtering his gimmick through the mouth of a character. Such is evident through Elmer reading the contents of the book aloud; it’s hard to imagine the phrase ”Pwesto!” Presto!” being present in the book itself had this cartoon been centered on another character sans speech impediment. Likewise with “You have a fine pictuwe of wiwdwife suitable fuh fwaming.”

Elmer’s Candid Camera seems to be an experiment from Jones on a number of fronts. Testing the waters with the freshly conceived Elmer and refinements on proto-Bugs are the most obvious, but certain staging and pacing decisions are another. While it’s no secret Jones loved his sculpted close-ups early on, Candid Camera features them in bulk. Juxtaposing them against single color card backgrounds enhances the uncanniness of their usage, as is seen through the very arbitrarily intimate shot of Elmer pontificating to the audience “Gowwy! That sounds simpew enough.” Allowing the shots to linger on for just a few beats too long accentuates the discomfort of the intimacy, as is again showcased through Elmer staring at the audience for an added second. The close-up adds nothing in terms of functionality nor clarity.

Such is a recurring theme throughout the cartoon. Similarly glacial pacing and unnecessary emphasis is delegated to a shot of Elmer perusing all of the equipment necessary for his pursuits. His recitations of each and every trinket (“Twipod, fiwm, camewa, buttewfwy net, fwashwight powduh, wens, cawwying case…”) seek to stress the acquisition of Bryan’s vocals—granted, the effect would have been much more successful upon the cartoon’s debut when audiences were thoroughly acquainted with his shtick. Today, the most novelty is derived from the “little giant camera kit” preceding the numerous trinkets courtesy of ACME in Jones’ Road Runner films.

Vestiges of Elmer’s prototype counterpart are most visible in the following sequence of him strutting along with his equipment, whistling a cheery accompaniment of “Sticks and Stones”. Though the outfit itself is the biggest giveaway, the comparatively squat stature and derby freely bobbing along on his head—as well as the mere act of walking and whistling, the exact thing he was doing when first introduced to audiences in Little Red Walking Hood—are all synonymous in demeanor. The main difference here is sophistication; that is, as much as one can call Elmer a sophisticated character.

What is certifiably sophisticated, however, is the animation. Particularly when Elmer comes to a stop upon the sight of rabbit tracks—a very subtle detail, his eye direction changes to look down at the ground just before he stops. Thus, noting the tracks and halting feels more believable and human rather than obeying an obstacle for the sake of forwarding the story.

Comparisons to the ever impending A Wild Hare eke their way out through Elmer’s noting of the tracks, history made as the first ever “wabbit” is uttered. While not to spoil too much of the plot (albeit a given) Elmer is just as incompetent of a photographer as he is a hunter. An overzealous obligation to the role does not necessarily equate the skills necessary for the job; both as a photographer and a hunter, a dweebish inferiority prevails in that his shoes are always too big for the job. Being an inadequate hunter is almost more excusable, as there is a lot of added weight that comes with the job. Inadequacy as a photographer, however (which certainly does require its own set of skills, but speaking with the Fudd in mind), accentuates Elmer’s role as—in Jones’ own words—a complete shmuck.

Nevertheless, Elmer’s failure isn’t completely owed to his own ineptitude. Unobliging wildlife play a great role in that as well. As such, we are introduced to our freshly redesigned unobliging wildlife in question taking a nap in the meadow. Elmer’s realization in the distance dutifully follows Jones’ current fixation on shaking head takes, serving as a bridge before quietly approaching the wabbit. His footsteps following the curve of the tracks places an emphasis on their presence, ensuring the audience understands that they lead to an end result rather than serving as mere decoration. It would have been easier for Elmer to cut straight across the screen rather than curve around the path, but the latter offers more coherency and rhythm in staging.

Like most of the pacing in the cartoon, Elmer’s attempts to set up shop drag on longer than they need to, but aren’t entirely for naught. A shot demonstrating his point of view from behind the camera is intimate and integrating, immersing the audience in the action. Not only that, it arms Elmer with an added sympathy by allowing the audience to experience the events of the cartoon vicariously through his own eyes.

Thus, his shushing a nearby bird bursting into song is more sympathetic and understandable given the amount of preparation put into the shot. Can’t risk any outside distractions waking up his subject.

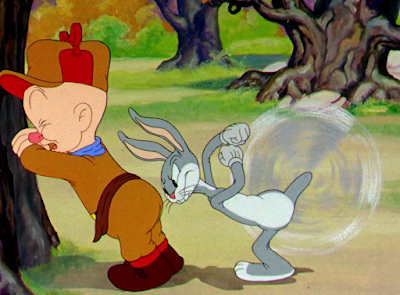

That includes the subject himself. Just as Elmer profusely shushes the bird, Bugs snaps his head up to silence Elmer with equal ferocity before reverting back to the same sleeping position. The dynamic between the two characters is thusly established.

Such is furthered through another POV shot from Elmer’s camera, this time fixated in clear view of Bugs’ rear. A sardonic trumpet sting of “You’re a Horse’s Ass” indicates this is no accident—likewise with the very purposeful maneuver of Bugs lowering said ass once Elmer engages in another series of bewildered spasms. The polite yet resolute contrarianism of the rabbit is indicative of his refined persona, in that his heckling arrives with an air of suave determination. Full frontal ass is no accident, and while Elmer may be oblivious to that, the audience is perfectly in on the joke.

All of the above could similarly apply to the adjacent sequence of Bugs strutting up behind Elmer as he prepares to take more photos and politely interrogates him. His unwavering confidence as he makes small talk with the photographer in question (“Whaddaya doin’, takin’ pit’churs?” Elmer nods in response, “Nice hobby. Mind if I watch?” An equally clear shake of the head no) is reliant not only on his nonchalance, but the expectation that Elmer will be oblivious enough to miss that the rabbit is gone. Bugs’ assumptions are correct, which is a success in itself. Again, certainly indicative of his refined self—just more hayseed in its delivery.

Indeed, Bugs has mellowed out considerably compared to his prior outings. That we’ve gotten more than two minutes into the cartoon without a single “a-hurr hurr” laugh is a major victory in itself. His voice is still unmistakably cornpone, which is additionally reflected in his design, but his heckling feels much less aimless, rapid, and screwy than what was first broadcast as a Daffy Duck clone by Ben Hardaway’s own admission.

Daffy’s heckling as he matured would become more impulsive, sometimes prone to error, more unpredictable, arguably more emotional and maybe even innocent—Bugs’ heckling is more calculated, a self indulgent hobby or defense mechanism given the context rather than necessary means of catharsis. There would certainly be an overlap between characters, and Bugs by no means is a character immune to impulse, but the differences between the two at their core are beginning to become more apparent, with A Wild Hare driving that home.

Jones’ acting for Elmer follows the theming of his pantomime cartoons in that his actions and thoughts are very clear despite no words—or, in this case, even visible facial expressions—being present. A mere nod of the head yes or shake of the head no provide all the commentary necessary, and he doesn’t bother to speak unless necessary. “Necessary”, of course, constituting a reply to Bugs’ inquiry of what he’s taking a picture of. Elmer’s sincere reply of “That wabbit” while making eye contact with his own subject before heading back to his duties is again another blueprint for further interactions between the characters to come.

Pacing for the entire dialogue sequence is unsurprising in its bloating. Bugs’ acting as he peers over Elmer’s shoulder and feigns laborious thinking is certainly effective, an oxymoronic sincerity in his certifiably insincere head scratches and elbow tapping, but pumps the brakes on what little momentum there is to even be had. There’s about 10 seconds between Elmer’s line and Bugs asking “What rabbit?” Regardless, it shines an inadvertent spotlight to Stalling’s curious, plucky orchestrations of “Piggy Wiggy Woo”, which sound lovely and provide a nice means of listening during the long lapses of dialogue.

Nevertheless, Elmer wrestling himself from beneath the photography cloth indicates a representation of his shifting attention, as well as a coming realization. Bryan is a fantastic voice actor in that he captures a strong, lovable sincerity in his vocals—Elmer’s voice trailing as he struggles to put two and two together sounds wholly genuine. Especially his “…ovew thewe!” that doesn’t sound convincing at all in the slightest and completely betrays his argument—exactly its intent. It’s as though he hopes Bugs will side with him and share the same vision of this miraculously disappearing rabbit.

Slow realization is still realization regardless. After a refreshingly brisk head take whose joyous snappiness is vindication for the viewer, Elmer indulges in another Jones fixation of the time—slamming two faces together in petrified cognizance.

While the beat lingers for much longer than the same example seen in, say, The Curious Puppy, the length of the gag contributes to the impending punchline. One of the most inspired pieces of dialogue—and acting—in the cartoon, Bugs pushes Elmer away only to remark, “Please, sir!”

Another disorienting, needlessly elaborate close-up is granted in the process. Intimacy in the filmmaking feels more warranted here than it did in Elmer’s introduction. Such tightness allows Bugs’ aside of “Gosh, I don’t even know the guy!” to feel as though it is truly directed to the audience in an act of amiable confidentiality. Aimless bobbing in his head movements hinders the impact and pacing, but the sequence is nevertheless a bright spot.

Instead, aimlessness manifests in a much hearty concentration with the following sequence. About 10 seconds of pure silence are delegated to Bugs glowering at Elmer in feigned accusation, Elmer awkwardly fidgeting and struggling to wipe the wabbit germs free from his body. While a nice gesture to see Jones place a heavier emphasis on character acting and personality, pantomime tendencies eke their way into a cartoon that is not exactly centered on pantomime. Pantomime requires different pacing, timing, focus, emphasis, acting—signals appear to become mixed at certain times, and knowing how much the characters could be talking or could be moving faster doesn’t allow such comparisons to fare well. Pantomime in itself isn’t the issue; directing with a different mindset for a different cartoon is.

Nevertheless, Bugs embarks on an equally elongated exit whose emphasis seems to beckon more than what actually results. From a contextual and historical perspective, however, there is more than what meets the eye—that he doesn’t flee the scene in a cavorting, “a-hurr hurr”ing frenzy indicates further growth and grounding in his personality. To see him stick to his guns on this feigned accosted personality indicates a certain conviction and awareness that wasn’t exactly present before.

Elmer turning around to begrudgingly face the camera reads as though he’s shielding his eyes from another impending heckler. Instead, it results in an awkward massage of the temples. Pregnant timing places an inadvertent spotlight upon the perplexing ambiguity, though his befuddlement is thoroughly conveyed regardless.

Befuddlement that is soon replaced with joy—a mild hat take indicates newfound exuberance towards a new subject. Indeed, focus on a squirrel gnawing on a nut reminds us that wildlife photography is not just limited to pesky rabbits.

Courtesy of more bumbling, almost infantile walk cycles, Elmer meanders his way over to the log to set up shop. No matter how bloated the action is, it looks solid—confident construction and tangible delicacy in movements that make for a very tactile result.

Further parallels to the future wabbit are concocted as Bugs pokes his head out of a hole in the log, visibly delighted at the prospect of messing with Fudd some more. To the credit of Jones, we don’t actually see Bugs climb into the log. Considering that the log is the complete opposite direction from where he left off in a huff, his appearance comes as a bigger surprise than what is to be expected.

Deliberateness and delicacy in his movements as he grabs the front of the camera bellows and pulls back serves as another fore-bearer to his future self. His heckling being the most obvious aspect, of course, but the purposefulness and almost conceited gingerliness in his hand movements all providing a window to his motives. The care in his motions indicates some level of thought behind his actions. While A Wild Hare would harness this most effectively by concealing his face entirely, introduced firstly through pantomime acting on his fingers gingerly feeling up a carrot, we have already been well acquainted with the character in this cartoon, so there isn’t as strong of a desire to hide him.

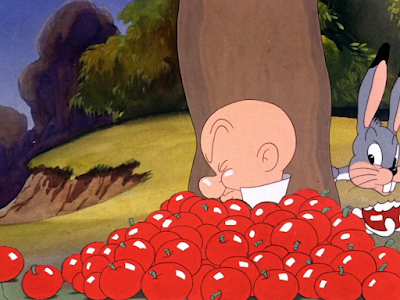

Impact of Elmer hitting against a tree is more kinetic than the bellows itself propelling him backwards, but the tree provides a more dedicated focus anyway. Focus that arrives through a profuse storm of apples raining upon the Fudd and completely covering him. Timing on the apples is succinct, absurdity and exaggeration thoroughly embraced in both speed and quantity.

Bugs strutting into the scene while gnawing on an apple himself is further insult to injury. Similar to the thought process behind his appearance in the log, there are no indications of him grabbing an apple that rolled into his vicinity, thus making his appearance feel all the more abrupt. The sort of borderline otherworldly, fantastical control he exercises—another keystone trait for the character—would be lessened had we been met with a laborious shot of him approaching the pile, eyeing an apple, dusting it off on his chest, perhaps sparing a snarky cornball line of dialogue and diving in to eat.

Such languidity is instead reserved for Elmer’s aimless, dazed head bobs. Likewise, one gets the idea that Bugs circling the screen and passing the foreground in perspective is purely to show off rather than add any sort of coherence nor functionality to the story.

The resolution is equally glacial in its preparation; Bugs glancing at the remains of his apple is unnecessary as is, let alone glancing back and forth a total of three times. Such could be said for his winding up to throw the apple, hand movements feeling somewhat weightless and glacial rather than impish and mischievous. Regardless, the manner in which he’s drawn—particularly the taller head—paint an image that is not entirely unreminiscent of his impending redesign.

His lobbing of the apple core directly at Elmer’s head yields welcome results in speed, too. Preceded by a bulging eye take from Elmer, animated on one’s to enhance the elasticity and spontaneity of the reaction, completely removing his head out of frame one frame before the core hits the tree further accentuates the abruptness of the impact. A newfound danger and threat is noted through such timing, exaggerated by Treg Brown’s echoing smack sound effect.

An inevitable topper arrives in a serviceable smack of one last apple exploding on Elmer’s head, leading the audience to ponder the solidity of his cranium for an apple to exude the physics of a tomato. Suspension of disbelief.

A transition in tone and acts is noted through the finality of a fade to black. We soon arrive to Elmer engaging in more photographic pursuits, attempting this time to capture a photo of a nearby bird.

Bugs’ arrival wryly informs the audience that no such luck will occur. Jones continues to flaunt his perspective by enabling Bugs to enter in the foreground; indeed, an added depth is bestowed to the composition, his passing through the foreground feeling comparatively more disruptive than if he had just walked up behind Elmer in the first place. It’s as though Bugs is interrupting not only Elmer, but the obstructing the view of the audience as well. All apply to Bugs’ nonchalant “Oh, there you are.”

Gratuitous head shakes that slow the pacing rather than contribute any substantial acting are shed before Bugs leans nonchalantly against Elmer and attempts to strike up more conversation. Yet again another indication of a growing shift, much of Bugs’ heckling here is from a verbal front, whereas his previous cartoons utilized broad slapstick as a means of riling his foes. Instead, he seems to know that just his presence is a nuisance in itself, and uses the opportunity to suggest that Elmer consider taking photographs of a rabbit—“that is if you are at, uh, all, uh, interested.”

Jones engages in yet another intimate close-up that feels more uncanny and suffocating rather than confidential and amusing. Still, Bugs’ animation is staggeringly solid, controlled, bestowing an intricacy and perhaps even one might go so far as to say “sophistication” that he has never been privy to yet. Sculpted shadows, particularly those on the eyelids, further the tightness of the construction.

No matter how awkward the close-ups may be, this one too serves a purpose in terms of staging. It provides a buffer so that the camera may cut back to Elmer now fully facing his adversary, fists and teeth both clenched as he growls like an angry puppy for 14 seconds straight. The maneuver is predictably more awkward than funny—the abruptness of his presence reads more as a staging error rather than deliberate attempt to catch the audience off guard (perhaps dedicating a few poses to him settling into that position would ease the flow), and the growling sound effects very obviously being prerecorded and sounding absolutely nothing like Arthur Q. Bryan don’t effectively embrace the caricature and whimsy intended by their use.

For comparison, Jones would eventually get a handle on the intended effect—just not here. A very similar maneuver is followed in My Favorite Duck released about two and a half years later; in it, Daffy breaks into Porky’s camping materials to fix himself a sandwich. As he does so, he unknowingly grabs Porky’s hand in the process, who is revealed to have been eyeing him down the entire time. There are zero indications of Porky's presence when the scene starts, and his cel is cheated to actually slide closer to the table, disguised by the movement of a camera panning over to his reveal. His appearance therefore comes as a genuine surprise, yet the staging is delivered in such a way that there is a connective smoothness which preserves the surprise aspect and clarifies it rather than catch the audience too off guard to be able to process it.

Regardless, the surprise aspect is the priority first and foremost here, and Jones certainly does achieve that. Ill-fitting and admittedly annoying as the dog growling sounds may be, solid animation is flaunted on both characters, particularly the head tilts on Bugs as he chalks up Elmer’s supposed refusal to take photos of rabbits as prejudice. With this “‘Course, if ya don’t like rabbits, eh… ya don’t… like… rabbits!” mindset in mind, Bugs stalks off yet again in a further attempt to mess with Elmer and put words in his mouth.

Seeing as he’s cast as a lowly photographer rather than lowly hunter, the closest means to a weapon he has is a butterfly net. Certifiably unimposing, that he struts around with the net in hand as though it possesses the same lethality as a fully loaded rifle is an amusing acting decision and suspension of disbelief. Weighted, uneven footsteps prompt the camera to start and stop, a solid immersion that enhances the believability of his emotional turmoil. The unsteady walk and attempts to be as imposing as one possibly can with a butterfly net both play equal parts into this.

Certifiably Jones-ian head shakes indicate that something has caught his eye. Indeed, the camera pans to reveal Bugs muttering and griping to himself as he staggers along; while this rendition of the rabbit is still far from being fleshed out or containing the nuances of his future self, he is much more “sympathetic” (if one could call it that) than his prior appearances. This is the first time we see him truly griping or complaining in any capacity about his foes—in this case, grousing that he hasn’t gotten his picture taken (“I’m a cute kid, why don’t they photograph me?”)

Bugs’ aggrieved ponderings provide Elmer an opportunity to capture him with the net. As such, it provides equal opportunity for Bugs to engage in his next act: tugging at the ol’ heart strings.

Faking death or harm has been a staple since his very first appearance in Porky’s Hare Hunt, albeit his performance in that cartoon was far from sympathetic and gave away its sardonicism in tone much too flippantly. While A Wild Hare proved to be the culmination of such efforts in one of his most iconic scenes, animated by the brilliant Bob McKimson, his feigned panic here is a solid step in the right direction.

Claims of being unable to breathe are wholly bogus, and both he and the audience know this. Still, his choking and pounding on the ground prove successful, as Elmer genuinely appears remorseful in another uncanny close-up; a much more solid improvement than Porky’s borderline disgust showcased in Hare Hunt.

Much of the success in such histrionics lie in the reactions of his adversary. Elmer’s sympathetic expressions further the believability of Bugs’ act, as though there truly is something horribly wrong with him, and allow the audience to subconsciously buy into the hysterics as well—even if we are meant to laugh at Elmer for being such a gullible sap.

Bugs is still hard to truly feel sympathetic for in this stage of his development, but the effect of his “death” as he flops to the ground with an ominous thud is much more synonymous to the hysteria seen in A Wild Hare than Porky’s Hare Hunt. Again, Elmer’s reactions (as well as the attitudes reflected in the filmmaking) are just as indicative of success as Bugs’ acting. In this case, a complete and all encompassing silence—no drumroll, no single note held out, just the dull hum of static—bestow a necessary, ominous weight and solid tension that make Elmer’s grief seem more realistic and warranted. The experimental color card background admittedly alleviates the effect just slightly, uncanniness in staging reducing the naturalistic intent, but Elmer’s tearful “I didn’t mean to huwt the poow, wittew gway wabbit” possesses a sincerity that makes the audience privy to sympathy. A comparatively mild reaction juxtaposed against his violent subs and claims of being a “moidewew” in A Wild Hare.

Likewise with Bugs’ reaction. While not as extreme as literally kicking his ass in Wild Hare, his jumping up at the last minute and throwing the net over Elmer instead is a much stronger and more amusing means of retaliation than his exit in Hare Hunt, where he merely quotes Groucho Marx before strutting away to play the fife. Here, netting Elmer actually has some semblance of a consequence.

That consequence being one of the highlights of Arthur Q. Bryan’s career. After Bugs struts off with more contrarian muttering (“Imagine flippin’ nets over harmless little rabbits. The SPCA shall hear of this!”) the viewer bears witness to the first fully fledged breakdown of Elmer Fudd. While Bryan’s acting carries much of the weight of the breakdown, character acting and design play a greet part as well—particularly the genuinely unnerving manner in which Elmer’s eyes peel open, maintaining that same wide eyed expression and grimace all through the meltdown.

Tearing himself free from the shackles of the net, Elmer is quick to completely obliterate his own equipment, ensuring “wabbit” becomes a certified part of the English vernacular through his circuitous yelling and screaming and condemnation of the creatures. Perhaps no delivery is as visceral as his “WIDEWIFE, AAAAAAAGH!!” upon spotting his discarded book—while camera motion on the book itself is unnecessary, it bestows added emphasis to its presence and justifies Elmer’s reaction. Additionally, uncanniness in close-up shots works to his favor; the tightness in composition paired with freneticism/ugliness in design and animation and raw emotion in vocal deliveries are all successfully and viscerally unnerving.

Likewise, his arm slinging, head grasping, fist knocking catharses as he screams about wabbits and widewife prove to be the most visually attractive aspect of the breakdown yet, crazed expressions reading as more appealing rather than wholly unnerving. His breakdown reaches its climax as he jumps into a nearby pond, yet again skirting by the foreground to both immerse the audience in the action and flaunt further perspective animation. His first outing with the character, Bryan has already made a long lasting impression and touts his vocal prowess, asserting himself to be a great character actor and more than just “that guy who does the funny voice.”

Jumping into the water does effectively bring Elmer out of his high, but lands him in equal trouble as he struggles to tread water.

Thus calls the attention of Bugs from off-screen, dozing against a nearby tree. After a series of more self indulgent Jonesian head shakes, he—in all of his amicability—comes to the rescue. While his changing into a wetsuit somewhat pads the pacing, it serves as both a callback to the anything goes mentality of Hardaway’s rabbit and fore-bearer to a long lasting extravagance in any and all of his schemes. Gotta be prepared for the job.

A rescue is promptly conducted, Jones and crew showing off—and rightfully so—by displaying the distorted reflections of Bugs and Elmer’s bodies submerged in the water, making the interaction between environments feel more believable and consequential.

Further praises must be sung towards Bryan’s voice acting. Upon Bugs’ inquiry on how Elmer’s feeling, his responses carry a profound genuineness in their patheticness; unconvincing “I feew pwetty good”s and “I feew sweww”s make it sound as though Bugs is consoling a toddler recovering from a tantrum rather than a middle aged adult having bad luck with his photography. Again, Bryan bestows a palpable sincerity to Elmer’s deliveries that are just as hilarious as they are sympathetic. Elmer is both a character who is incredibly sympathetic and not at all—the audience is inevitably meant to root for Bugs in most of their outings, but in instances such as these where he doesn’t pose a significant threat, he’s reduced to a total sap and meant to be pitied. Laughed at, yet pitied.

Their back and forth banter thus results in another simultaneous piece of throwback-and-foreshadowing; while Bugs kicking Elmer in the ass to send him plummeting into the waters yet again hints towards Bugs kicking him up a free after his histrionics in A Wild Hare, the return of the dreaded “a-hurr hurr” laugh as he does so indicates that he is still Hardaway’s rabbit at his core. Thankfully, that isn’t for long.

We therefore iris out with that in mind, a certifiable end arriving with Elmer literally getting the book thrown at him.

Before divulging into my own thoughts, I’ll let Chuck Jones say his piece on the cartoon, taken from his memoir Chuck Amuck: The Life and Times of an Animated Cartoonist:

“…we find Bugs stumbling, fumbling, and mumbling around, vainly seeking a personality on which to hang his dialogue and action, or— in better words than mine—‘walking around with his umbilical in his hand, looking for someplace to plug it in.’ It is obvious when one views this cartoon, which I recommend only if you are going to die of ennui, that my conception of timing and dialogue was formed by watching the action in the La Brea tar pits. It would be complimentary to call it sluggish. Not only Bugs suffer at my hands, but difficult as it is to make an unassertive character like Elmer Fudd into a flat, complete shmuck, I managed. Perhaps the kindest thing to say about ‘Elmer's Candid Camera’ is that it taught everyone what not to do and how not to do it."

While Elmer’s Candid Camera is plentiful in its sluggishness, Jones’ critiques come as a bit of a surprise—there are plenty of other cartoons of his that are just as glacial, if not more so, that don’t have the added benefit of entertainment through such compelling or established characters. I also think that is where his criticisms stem from in the first place; being the first outing with Elmer and Bugs, essentially establishing their dynamic and setting a precedent for future cartoons to come, there is a stronger protectiveness and inadequacy that comes from comparing this short to those that follow rather than comparing it to the cartoons that led up to it. His criticisms are understandable, but a tad hyperbolic—then again, artists tend to be their own harshest critic.

Indeed, Candid Camera suffers from bloated pacing and awkward shots, but is much closer in tone to A Wild Hare than any Bugs cartoon that has come before it. Though still a relatively unendearing character, Bugs has much more charm in this short than his previous outings through Jones’ refinements and decisions to make him more grounded, cognizant, even cynical—Elmer’s Pet Rabbit would follow the same patterns with a very aggrieved rabbit. Likewise, as mentioned previously, Elmer’s inadequacy as a photographer is synonymous to his inadequacy as a hunter in that both jobs have shoes too big to be filled in.

Arthur Q. Bryan is the certifiable star of the show and makes a great case for the impending popularity of the character. Blanc works well with what he’s got, though Bugs’ hayseed voice is incredibly unattractive by design. Thankfully, the comparatively calmer demeanor he exudes here renders his vocals less grating and harsh on the viewer. Saving his dreaded laugh for the very end of the cartoon indicates good changes are coming to the character.

Through its filmmaking, Elmer’s Candid Camera reads almost as an experimental film, which could perhaps explain the later Jones’ dissatisfaction with the cartoon. Intimate close up shots against color card backgrounds are more uncanny than they are intriguing, but do succeed in calling the audience’s attention to the composition of the scene. Likewise, an abundance of perspective shots and depth in staging overall seek to further immerse and integrate the audience into the action. Candid Camera is very much a vicarious cartoon, with both Elmer and Bugs expressing confidential asides to the viewer—often through the maneuvers listed above. There is a tangible self awareness present in the way this cartoon conducts itself that has not been present in any of the Bugs cartoons prior. Soon, self awareness would be a defining factor of the character.

With this being such a milestone cartoon, it becomes easy to compare it to the shorts that come afterwards rather than before. Yes, compared to the Bugs and Elmer cartoons that follow, this one can easily be written off. However, at the time of its release, it fares relatively well. Animation is solid and confident, defined, Stalling’s musical accompaniment and Brown’s sound effects effectively enhance the short and fill in the gaps lapses in pacing may create, and a prioritization of visceral character acting is always welcome. If anything, it is a keen signifier of the immediate change that is impending. Elmer’s Candid Camera walks where A Wild Hare runs.

Conveniently, a great wealth of production art for the cartoon survives online. Here are a few additional cels and lobby cards from the short to end off on:

slight correction: there aren't any gloves on this bugs design, looking at it; afaik they just colored his hands white

ReplyDelete1937 still actually marks the debut of Elmer Fudd, no matter what he looks, acts, and sounds like.

ReplyDeleteThe opening to "Porky's Hare Hunt" as a 1937 copyright date under the WB Sheild. So, 1937 marks debut of Bugs Bunny as a little White rabbit as well.

ReplyDelete