Disclaimer: This review entails racist content and imagery intended for historical context. I ask that you speak up in the case I say something that is harmful, ignorant, or perpetuating so I may take appropriate accountability. Thank you.

Release Date: March 16th, 1940

Series: Looney Tunes

Director: Bob Clampett

Story: Warren Foster

Animation: Norm McCabe

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Porky, Cook, Sailor, Chief), Robert C. Bruce (Narrator, First Mate), The Sportsmen Quartet (Chorus)

(You can find the cartoon for yourself here.)

Though Africa Squeaks hadn’t been released to the public at the time of Pilgrim Porky’s conception, the borrowing of Tex Avery’s travelogue format proved to be an evident success, if only to Clampett himself. His reuse of the setup indicates some fondness to be had for its convenience. Travelogue spoofs were a quick way to get a laugh from audiences well acquainted with the source material on which these shorts lampoon, as well as providing ample opportunity for a showcase of self indulgent gags that didn’t have to oblige to a tight story. Likewise, in Clampett’s case, shoehorning star characters such as Porky into the film (even if he hardly has any relevance, despite the title) proved another selling point for audiences. This ain't any old travelogue—we got the pig in it!

As such, Robert C. Bruce resumes the dutiful role as the ever pleasant, self important narrator guiding us on our voyage. Whereas Kristopher Kolumbus Jr. casts Porky as the eponymous colonizer, we witness his point of view from the lens of a pilgrim leading the voyage of the Mayflower and all of the corresponding hijinks therein.

Concentrated with typical Clampettian cheaters (establishing title card disclaimers and lengthy establishing shots) as the opening may be, the means of approaching them are at least somewhat unconventional; with an animated title sequence boasting bobbing ocean currents in the background, a passing wave completely drowns the title card to reveal the next piece of business. A whimsical maneuver that hints at the forthcoming tone of playful hijinks.

Sure enough, through situationally antiquated typeface the audience is acquainted with the story’s setting. A beat enables the viewer to digest the scribe, particularly claims of a “quaint little seaport town” of a thousand souls…

…and a few heels. Though Warren Foster gets the writer’s credit, the politely amusing at best and groan inducing at worst punnery is more akin to Clampett’s taste in humor. Allowing the punchline to fade onto the screen rather than display the entire joke at once does help to exaggerate the intended impact, seeking to catch the audience off guard.

Vestiges of influence from Porky the Gob manifest not only through the distortion glass creating ripples on the water, but the gradual transition to daytime as well. In this case, the scene here has the added benefit of Robert C. Bruce’s narration. Dick Thomas’ discrepancy in value and lighting in his paintings make for a rightfully moody and serene scene, lights emanating from nearby windows being of particular note.

A shot of the “hopeful pilgrims” indicated by Bruce’s narration does not exactly maintain the same visual splendor, more so aimless waving and gratuitous motion rather than appearing as a snapshot of the action itself. Regardless, the upward angle of the ship encourages dynamism through imposing perspective and diagonal angles, succinctly capturing the view of an onlooker peering up towards the vessel.

A cross dissolve thus introduces one captain Porky. As mentioned previously, Porky’s role holds very little significance in this short—at least compared to Kristopher Kolumbus Jr. He’s cast as more of an observer, a physical prop to introduce unrelated gags or bridge sequences with a few spotlights granted in between for courtesy. Said spotlights are mainly sprinkled in the beginning as he barks orders—a “Hurry up, fellas! Raise the gang-eh-puh-p-ih-plan-eh-p-eh-p-eh-p-pp-eh—aww, leave it down,” seeks to capitalize on his stutter more than personality. It remains amusing nevertheless in spite of asynchronous animation not matching the acting nor lip sync of his dialogue.

An arbitrary cut to the same shot of the pilgrims—albeit the camera at a tighter register to mask the reuse—is lazy and unnecessary, camera lens somewhat unfocused.

Regardless, it seeks to provide a bridge to the next shot, this time animated by John Carey. Though Porky’s “Aaaaall a-buh-be-bih-eh-boooard!” is unmistakably his, Clampett engages in a creative, somewhat unorthodox maneuver—Bruce assumes duties of dialogue, his order of “Ship the gangplank!” reflected in Porky’s lipsync as though he’s transcribing Porky’s dialogue himself, unobstructed by a stutter. It certainly furthers the travelogue notion, almost comparable to a montage, viewing a sequence of events and film-within-a-film rather than experiencing them 100% vicariously.

While Bruce heartily recites a plethora of navy commands (for those wishing to hear a stolid narrator claim “Shiver m’ timbers!” in a most joyously milquetoast delivery, now’s your chance), visual gags take precedence as a pilgrim raises a mast net while climbing it at the same time. Treg Brown’s cranking sound effects birth the sight with an added tactility, added coherency and rhythm added through Carl Stalling’s xylophone accompaniment harmonizing with the prevailing score of “Song of the Marines.”

“He-he-hoist the anchor!” Perspective of Porky barking the command directly at the camera seeks to ease monotony in the back and forth pacing, as well as soften the disconnect between the audience and onscreen antics that a travelogue format often establishes.

Anchor is he-he-hoisted courtesy of some grotesque slurping sounds and the visual of the anthropomorphic ship swallowing the metal like a giant noodle. Details of it licking its lips are somewhat unnecessary, yet unapologetically so, furthering the conviction to the sudden anthropomorphism.

Similar transformative properties follow in the logic of Porky operating the ship through the convenience of a trolley. Instead of going through the motions with a trolley sign metaphor and nothing more, scrolling through a variety of locations before settling on America (as he does indeed do), the metaphor is carried all the way so that a certifiably modern trolley car is built right into the ship. An embrace of the absurd is what makes Clampett’s shorts so lovable, even if gags such as these are polite in comparison. A few rings of the bell cement all of the above points and mark loyalty to the symbolism. Worth noting, Porky would appear with a thinly disguised cameo in Clampett’s The Great Piggy Bank Robbery as a trolley driver.

Less lovable is a gag recycled from Johnny Smith and Poker-Huntas of the boat literally shoving off, a boot-clad mechanism propelling off of a nearby dock. Tex Avery and Bob Clampett’s sensibilities are both similar enough that the reuse doesn’t at all feel out of place, especially following the themes of the aforementioned transformations, but nevertheless arrives as a cheat—not out of place for certain gags to follow.

Overzealous camera moves accidentally telegraph the forthcoming “gag” of the ship steering away from a lighthouse at the last second. The visual would have maintained the same clarity and intent without a needless truck-in, which only disrupts the flow and forces the audience to expect a rebuttal. Really, the only thing that could constitute the business as a gag in the first place are the brake squealing sound effects. Otherwise, a redundant piece of business that isn’t very funny. Perhaps the novelty was stronger in 1940.

What is more novel today, however, are further anachronisms on the ship’s stern. License plates, bumper stickers, and blinkers all beckon the likes of a modern 1940 roadster. Tex Avery followed a similar structure again in Johnny Smith and Poker-Huntas, a bit more explicit in his theming with an outboard motor. The shot here lingers for slightly too long and lessens some of the polite amusement of the gag, but is certainly a bigger improvement than the former scene.

On the topic of Tex Avery, The Isle of Pingo Pongo is channeled in the coming gag of Plymouth literally disappearing from the horizon. That is, propelling itself out of the ocean with great sentience and splashing into the distance. Kristopher Kolumbus Jr. borrowed a synonymous variation of the gag, but the elongated spotlight here and shared intent in narration bridge Pilgrim Porky and Pingo Pongo more strongly.

Thus provides ample opportunity for a song number. While a shoehorn to pad time, there is a stronger notion of purpose behind the musical’s inclusion in that we see the actual chorus (pilgrims aboard the ship, vocals provided by the ever talented Sportsmen Quartet) rather than obscured in some void to play over completely unrelated visuals. Set to a chorus of “Life on the Ocean Waves”, said visuals are par for the course—the statue of the baby on the ship’s bow gargles a fresh mouthful of saltwater, a tramp tips the rim of his ragged hat, and so on.

Regardless, there are brief moments of inspiration, the strongest coming from the pilgrims pausing the song number to throw up in correspondence to their line of “We’ll make the trip by rail.” Completely suspending any and all music and replacing it instead with the ominous din of gurgling ocean waters exaggerates and embraces the abrupt halt, doing everything in its power to call attention to the gag. Always a fan of height difference gags, Clampett and John Carey, who animates the scene, have the littlest pilgrim kicking his stubby legs to indicate the gastrointestinal turmoil being experienced.

Our song number ends on a gag recycled from Porky the Gob. A brief shot of a singing sailor preceding this one masks some laziness, as it subconsciously prepares the audience for an impending punchline and therefore touts the slightest bit of preparation in the recycling, but not by much. Here, a wave engulfing the sailor and replacing him with an equally jovial seal has the benefit of arguably more attractive Clampett design sense.

Perhaps most intriguing is not the gag, but the transition that follows—iris wipes are certainly not uncommon, yet wiping to a completely opaque, black iris is. It feels somewhat more kitschy, niche, novel than a regular transparent iris, and certainly more playful than a cross dissolve or fade to black. A swift transition into a new act, but not one that is blind sighting.

“Captain Porky keeps a careful record of the vessel’s progress in the ship’s log.” Wordplay reflected on the papers is politely amusing through its brusque nonchalance.

Equally amusing—if not moreso—is the following shot of Porky deep in thought, mulling over his duties as captain. As a viewer, we are privileged to bear witness to such taxing mental calculations and the intimacy therein, reflected through equally stirring monologuing: “Ehhh… leh-lemme see now, eh-luh-lemme see… eh-nuh-neh-nn-nothin’ happened yesterday… an’ nuh-nee-nothin’ happened.. so far today!”

Facetious orations aside, it does come as a bright spot in the short, aided through the rhythmic visuals of the ink quill spilling its contents due to the rocking of the boat, absorbing said contents once the vessel lurches the other way, and so forth. Blanc’s mutterings are so quiet that the music almost drowns him out, but there is a certifiable sincerity in Porky’s voice that makes a potentially dismal looping shot endearing and funny. It almost sounds as though he’s surprised, just now coming to the revelation of these nothin’ happenings himself—the disconnect between the laborious “lemme see now”s and Bruce’s description of keeping a careful record juxtaposed with the grand result of absolutely nothing is just as enticing. Great character acting that holds the audience’s interest through an otherwise static, looping shot.

Inspiration nevertheless strikes through the courtesy of a typewriter metaphor. Clacks and dings of a typewriter carry the illusion much more than the animation; if one were to view the scene without sound, it would read as oddly paced and possess a mechanicality that is accidental more than purposeful. It nevertheless matches the overriding tone of the cartoon well enough.

On any cartoon centered around pilgrims, harmful racial stereotypes are a given, particularly delegated to Native Americans—Clampett goes for the gut by recruiting harmful Black stereotypes as well as we follow the adventures of the galley’s cook. Here, Bruce recommends a course of fish for dinner, which is met affirmatively through the cook’s Eddie Rochesteresque dialect.

The window in the background isn’t entirely for decoration—it provides a means of transportation for the cook to dive out of and get the fish fresh from the source. Background details bring some of the most amusement today, particularly the two socks hanging on a clothesline in a dangerously close vicinity to where the food is prepped. Likewise, errors persist such as the pan of the clouds outside coming to a momentary halt when the chef grind at the offscreen narrator or having two cels of the chef on a single shot; bloated pauses between lines and actions don’t particularly fare well either.

Same bloating leeches into the adjacent scene of the cook holding up a fish and judging Bruce’s approval. Between his “How’s this one, boss?” and Bruce’s mildly condescending “No, that’s a little too small,” there’s about 3 seconds of silence substituted only by Stalling’s orchestrations of “Jeepers Creepers”.

That we wipe diagonally to the next line of business indicates we will be following the cook for quite some time. Hopefully results will yield a comparatively funnier outcome—any humor to be had stems purely from the Rochesteresque dialect and stereotypes as a whole rather than actual jokes. Diving out of the window is amusing, and his success in snagging a fish with such ease could be interpreted to feel the same, but the entire segment is otherwise unremarkable.

“On our second day out off our leeside, we sight a group of flying fish.” A static overlay of Porky staring vacantly off the ship calls more attention to his lack of prioritization rather than fix it. The shot would have maintained the same weight and functionality had Porky not been included—it reads as gratuitous and revisionist rather than actively helpful.

Nevertheless, focus is meant to be delegated to the shot of the fish flying over the waters in mini airplanes. A gag first seen in You’re an Education, Clampett and company have the added benefit of lingering on the gag longer and comparatively more thorough designs.

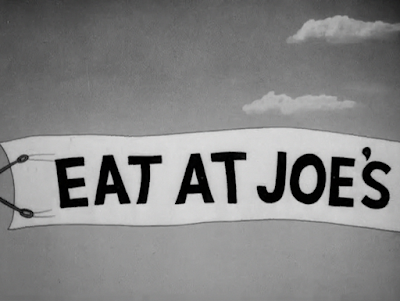

That, and an added punchline. An “EAT AT JOE’S” banner yet again foreshadows the likes of The Great Piggy Bank Robbery. A shift in music scores from “Sobre las Olas” to “The Umbrella Man” upon the sign’s entry inadvertently signals the audience to laugh upon the juxtaposition.

Another somewhat redundant Porky shot is thankfully rendered less arbitrary through actual movement. Though the motion is slight, idle, John Carey animates his observant of Bruce’s self described turbulent seas as the camera pans away to focus on the choppy waves in question. “The sea becomes turbulent… the waves grow choppy… and whitecaps appear!”

A literal transcription of Bruce’s comments promptly ensue. Disgustingly tactile “PUT!” sound effects as the caps are propelled forth provide added novelty in a gag that is groan inducing on paper, aided further by the sheer quantity of the hats, an appropriate score of “Put On Your Old Gray Bonnet”, as well as a generally innocent devotion to the joke. Clampett’s wordplay and literal metaphors tend to be playful and naïve in tone, rendering them easier to stomach than the obligatory, forced sardonicism present in a Ben Hardaway gag of the same kind.

Ferocious lightning strikes put an end to such antics. Clampett’s cutting and transitions between scenes could have a tendency to be a little disjointed, so it’s very possible that the jolt of the lightning arriving with zero warning could be more accidental than it leads on. However, assuming the abruptness is intended and purposeful, it’s certainly a powerful and effective maneuver; the bolt does feel unprecedented, spontaneous, breaking the audience out of the domesticity of the prior gag.

Attempts to accentuate the roughness of the sea by focusing a shot on the ship itself falls flat. Namely, the gag seeks to have the ship wrap itself dutifully around the arcs of waves forming beneath it. Exaggeration necessary for the gag to stand is not present, especially seeing as the ship only hugs the curves of one single wave. A very mild take that reads more as an interference in momentum rather than a joke.

Thankfully, more lightning gags fare better; the likes of What Price Porky is channeled through seemingly edible clouds. Whereas a duck in the former used two clouds to form a sandwich out of a chick’s hotdog hot-air balloon (that unabashed absurdity having lessened, or at least arrived with more explanation in the two years since), here, lightning bolts form the shape of a knife and fork and diligently cut off a piece of a cloud.

Crunching sawing sound effects bestow added tactility and permanence to the visual, as well as functionality. Instead of the electric cutlery serving as the joke and nothing more, the gash cut in the cloud enables a ferocious rain storm to erupt as water drains from the laceration. Clever and playful in itself, that it provides a transition to the next chain of events strengthens its foundation further.

Such treacherous conditions provide ample opportunity for more gags. Channeling again the likes of Tex Avery, a disembodied hand slides a title card into the scene that reads THE RAINS CAME. Following the philosophy of the cartoon’s establishing typography, the punchline “(from the picture of the same name)” fades into view rather than being introduced all at once. The gag is thusly savored through such an additional pause.

“Look! We’re headed for an iceberg!” It seems the storm seeks to provide additional dramatic ambience rather than serve as an independent obstacle as focus is promptly shifted.

A close up of a cross-eyed sailor keeping guard allows Clampett to engage in self indulgent screwballisms, whether it be from the anthropomorphic binoculars folding over themselves—a leftover from Kristopher Kolumbus Jr.—or the jowl flapping bellow of the sailor’s “ICEBER-R-R-R-R-R-R-R-G!”

Bruce’s “Look out! We’ll crash!” is too disconnected and bludgeoned by an awkward pause to read convincingly, and most of the dramatics rely on his voice and Stalling’s music—likewise, the cutting between angles and shots is much too slow to evoke any real sense of danger. Instead, the statue of the baby on the ship coming to life and covering its eyes seeks to evoke playful pathos where drama does not. Clampett loved his cuteness, so such a vignette intends to be indulgent just as it is amusing.

With all of that strenuous, heart clutching, gut wrenching build up in mind, the audience is equally amazed and flabbergasted by the resolution: the iceberg splits in two like a bridge to allow the ship through.

Again, like most of the gags showcased in this short to begin with, the novelty was much stronger in 1940 than it is presently. It certainly doesn’t help knowing just how wild and innovative Clampett has been before this and would become again, making these jokes pale in comparison. Nevertheless, the tension and buildup feels much more shoehorned and gratuitous rather than actually dedicated. Awkward pauses and glacial cuts further hinder the momentum; a vague incoherency prevails.

After a shot of the baby wiping its brow in relief, another indication of Clampett’s attachment to cute vignettes, the storm miraculously becomes irrelevant as we return to the chef still diving for his fish.

Bruce is, likewise, still dissatisfied. Thus, we promptly move on from the chef through the courtesy of a jump cut that is a bit too fast and jarring in its delivery to an entirely different scene. The chef’s appearance feels much more like an obligation as a result.

“Finally, evidence appears of approaching civilization!”

That the first visible piece of evidence of the civilization in question is an empty beer bottle is rightfully funny through its wry subtlety. At least, subtle compared to the gags that precede it. Further miscellaneous pieces of trash and empty goods flow into the ocean, though the beer cans and bottles are certainly the proudest in their appearance.

More playful anachronisms succeed a gratuitous shot of a happy Porky delighted to find land. Like the opening, any sliver of water in the shot is filtered through distortion glass to give it a more realistic, tangible quality.

Statue of Liberty gags are another must. Whereas Kristopher Kolumbus Jr. turns a Statue of Liberty into a cigar store decoration, Clampett and Foster rely less on stereotypes and more on the newfound novelty of the land. While the pan to reach the statue is slightly too long (as is the prior shot focusing on the signs, any attempts to pad out time worth trying), the discrepancy between the looming shadow of the real thing and the reveal of a toddler sized statue instead is effective and funny. Had the short been made just a few years later, the “age 3” almost irrefutably would have been replaced with “age 3 1/2”, a reference to The Abbott and Costello Program’s Little Audrey. The show itself would debut in July of 1940.

“With the long journey almost over, captain Porky carefully eases the Mayflower into Plymouth Rock.”

Another takeaway from Tex Avery, the aggressive race car sound effects as the vessel ensures to defy as any notions of “careful” as possible carry the juxtaposition and joke itself. While not to the same overzealous speed native to Avery in shorts such as Land of the Midnight Fun, very few come to replicating his speed as is—the sound effects are a great safety net where animation has the potential to fail. A successful safety net at that.

Dump truck metaphors as the ship unceremoniously dumps its passengers fades better on paper than execution; while understandable given the sheer size of the crowd and demand of the visuals, the passengers are drawn beyond recognition, barely defined hats loosely attempting to keep it coherent. Nevertheless, trust in the audience to get the gist is exercised, and the prevailing sound effects yet again enhance and pad what little visuals are there.

With less than a minute left in the cartoon’s runtime, it is admittedly impressive that we haven’t run into any Indigenous stereotypes up until this point. They are by no means spared, but it seems Clampett exhausted all of his “meeting the Native Americans in the new world” gags in Kristopher Kolumbus Jr.

Instead, a “Chief Sitting Bull” lives up to his name. Standard insulting broken English ensues…

…which, as was the case in Kolumbus, provides a springboard for screwball antitheses and radio catchphrases. Upon telling Porky he hopes he likes the country, thus launches into an excuse to channel the likes of Elmer Blurt from Al Pearce and His Gang, guffaws a-plenty as he hawks “I hope, I hope, I hope, I hope, I hope!” John Carey’s drawing style is immediately recognizable from not only Porky’s appearance, seeming more rotund, solid, taller eyes and a wide snout, but the sharp, curving forehead on the Chief—a design trademark of his that makes for another easy identifier.

With that obligation out of the way, the cartoon comes to an end as focus shifts back on the chef hunting for fish. Or, more accurately, the narrator’s polite curiosity at how the chef is doing.

Had Clampett ended the short with the punchline of the giant fish emerging from the water and mirroring the chef’s dialect of “How’s this’un, boss?”, it would be a corny yet serviceable end.

Instead, novelty of the gag is dredged and stretched far longer than necessary, killing quite a bit of its impact in the process. Namely the chef poking his head out of the fish’s mouth and responding “That’s good!” to Bruce’s affirmations. Blanc’s intonation in his delivery almost seems to hint as though there was more to follow, not exactly reeking of finality. Likewise with the music, which postpones its closing orchestral fanfare for a few more beats as though to accompany another line of dialogue. Instead, we are met with an awkward pause that deflates any semblance of impact the joke once had. A fitting end, one supposes.

Outside of stereotypes and subject matter as a whole, Pilgrim Porky is a rather disjointed, at times incoherent cartoon that flounders when compared to its unofficial prequel, Kristopher Kolumbus Jr. As mentioned in the review of the former cartoon, Kolumbus is by no means a perfect short, burdened with even more harmful stereotypes, but it is at least consistent and firm in its intent. Porky has more relevance outside of providing a visually cute segue into some self aware corny wordplay, and gags as a whole feel more intertwined with the story and characters rather than as a vague assortment of punchlines.

Pilgrim’s biggest sin is utter mediocrity. It isn’t actively terrible by any means. Racial stereotypes are an obvious turnoff, but even those feel more shoehorned in than normal—which says a lot. Instead, it’s just an incredibly boring cartoon. Whether as conspicuous as a song number or as subtle as a single shot being held out for three seconds too long, one can definitely sense Clampett struggling to meet the runtime’s quota, which leads to some sloppy cutting and general vague, incoherent filmmaking.

Of course, there are its bright spots. Corny as the gags may be, there is a prevailing mischief to most of them that bestows a certain innocence Clampett excelled at. Lightning bolts forming kitchen cutlery is a particular example of note. Likewise, the ship’s log section with Porky laboriously mulling over a hard day’s work of absolutely nothing is refreshing through its character acting—it’s the closest thing we really get to such with him in this short. Stalling and Brown do what they can with their respective mediums of audio, Thomas’ backgrounds seldom have opportunity to shine but do excel towards the beginning, and Bruce does a wonderful job as always as narrator.

Regardless, if nothing else, it’s a cartoon that succinctly encapsulates Clampett’s growing fatigue. Fatigue at bowing to mandates and shoehorning Porky into cartoons it’s very obvious he didn’t create with the character in mind, fatigue at having to pump out so many shorts, fatigue at trying to find ways to make the audience laugh when, to paraphrase himself, the animation itself wasn’t at a point where it could be relied on consistently for humor, and just general fatigue. Kristopher Kolumbus Jr., in spite of its own problems, scratches the itch the audience may get while watching this short in a more concise and devoted manner.

.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment