Release Date: April 27th, 1940

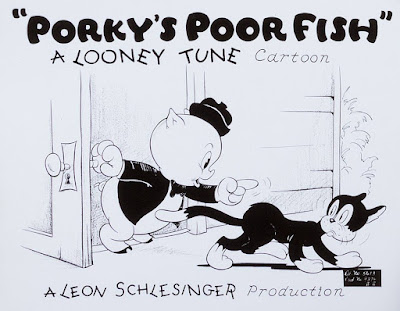

Series: Looney Tunes

Director: Bob Clampett

Story: Tubby Millar

Animation: Dave Hoffman

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Porky, Mouse, Whistle, Cat, Tuna, Turtle), The Rhythmettes (Chorus)

(You may view the short here or on HBO Max!)

Before getting down to the introduction, I’d like to note a significant change to the reviews. (A good one!)

Voice expert and historian Keith Scott has recently come out with a two volume book: Cartoon Voices of the Golden Age, 1930-70. In the second volume, he has graciously compiled a list of voice credits for thousands of cartoons. One of those thousands entails the Warner Bros. filmography.

This is a game-changing development that will graciously impact the future of these reviews. Up until now, a vast majority of common knowledge on these voices has been pure speculation, gambling with staggeringly unreliable sites such as IMDb. An expert in his field, Keith has put decades and decades of research into his findings. This makes the next 700 or so cartoons left to review much easier and eliminates a lot of rightful confusion.

Previous reviews have all been updated with the correct credits—for example, film editor and sound man Bernard Brown supplied the voices of both Bosko and Buddy for quite some time. Tex Avery voices the Andy Devine pig in My Little Buckeroo, not Tedd Pierce. Sara Berner’s first appearance in a WB cartoon wasn’t until Daffy Duck in Hollywood. Martha Wentworth voices the mad bomber in The Blow Out rather than Lucille Laverne, the vocal chorus in Porky's Romance was The Three Dots of Rhythm of whom Frank Tashlin's wife was a member of, and so on. Little details, but incredible to know and very helpful in ensuring that the history of these cartoons are preserved and noted with as little misinformation and confusion as possible.

While I very much could have made a separate post for this all on its own, I wanted to ensure that this development gets noted and that Keith gets proper credit, as this is a very exciting and again, very, very noteworthy advancement. I absolutely recommend his book to anyone curious about the history of golden age cartoons, and thank him profusely for his findings.

On that note, Porky’s Poor Fish arrives as a domestic take on Tex Avery’s Fresh Fish in more ways than one. Outside of borrowing a handful of gags from the latter, Poor Fish confines the creatures of the ocean into a pet shop—a convenient vehicle to showcase a vast array of gags with little explanation for their appearance required. Likewise, haphazardly tossing Porky into the role of the store owner crosses off that contractual obligation. Especially when Porky himself makes a very apparent point to abandon the cartoon halfway through.The cartoon’s title doesn’t entirely hinge on the abuse the eponymous fish will suffer from the hands of a hungry cat, but also serves as a reference to Art Young’s “The Poor Fish” segment in his political magazine Good Morning. A satire on capitalism, Young published the magazine as an attempt to appear innocuous in an age where such papers were banned for their “radicalism”. A more in-depth look at the legacy of Good Morning, The Poor Fish, and Young’s philosophy as a whole can be found here.

While lampooning capitalism Porky’s Poor Fish does not, it certainly does have its fair share of burlesques, which can be seen through the cartoon’s opening disclaimer. Groan inducing as the take on 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea may be, novelty of the disclaimer is somewhat restored through the decidedly Art Deco design of the title card. Somewhat misleading given the deliberate absence of sophistication in the cartoon’s premise, but fitting in that deception seems to be a theme for the short’s opening.

That is, almost a minute is delegated to a completely unrelated cat and mouse segment that bears absolutely little weight on the cartoon’s premise outside of introducing the cartoon’s antagonist and hinting at an impending bookend. A plump little mouse is introduced by whistling the short’s opening title accompaniment of “The Girl with the Pigtails in Her Hair”, performing a rather stilted, weightless skipping cycle over a vast background pan.

Where mice skip, cats lurk behind. Much of the visual interest is maintained through a painted overlay of various objects and pieces of trash in the foreground—discarded pots, planks of wood, broken glassware. Likewise, the ground appears dirty, fence posts in the background bent and warped; much of the short’s appeal is derived from the cartoon’s layouts and Dick Thomas’ painting skills. A regard for lighting and reflection in glassware persists that has seldom been seen prior; with a short dominated by so many fish bowls and the like, it’s a logical conclusion.

Camera registry issues occasionally pepper the cartoon, such as the first instance of the mouse turning a corner around the fence. While clarity isn’t muddled to the point of incoherency, his walking and skipping still as mechanical as ever, the blurriness does somewhat distract—at least compared to the previous and forthcoming scenes.

Benefits from the mouse’s purposefully stilted walk cycle arrive from antithesis. After a handful of shots of the cat mimicking the skip—the baby calf’s gallops from Porky’s Last Stand appearing to be a model of inspiration—the more organic timing and spacing as the cat pokes his face around the corner, head reverberating from the overzealousness of his energy, is a welcome juxtaposition.

A widening of the camera allows the audience not only to digest the cat’s ravenously nefarious glances, but to give room for his running start after the mouse. Poor Fish is, admittedly, not an attractive cartoon—characters have a tendency to feel mushy, loose, and just plain ugly. Some of that looseness manifests itself in the cat’s eyeballing takes, features (such as the muzzle) unanchored to the overall construction. Still, such ugliness is appealing in its own right, especially for characters meant to feel ugly and antagonistic. Therein lies the cat.

Much of the storytelling in the opening is conveyed through repeated shots alternating back and forth. The cat darts after the mouse in a fast camera pan (monotony eased through a bold, opaque overlay of some grass, encouraging naturalism in the staging), a shot is delegated to the mouse retreating in a hole, and the camera returns back to the pan of the cat skidding past the fence and crashing off screen. Such repetition encourages coherency, rhythm, momentum, which is certainly true with the pans—the camera pans back to the cat running following the shot of the mouse rather than just cutting back to the cat in the first place and prompting a jolt. Likewise, such repetition saves a few bucks and a few animation drawings—a bonus Clampett always sought out.

Various piles of discarded junk prove to have a purpose beyond aesthetic embellishments; the cat skidding to a halt and crashing off-screen is implied to be all the more violent as a result. Treg Brown’s sound effects do the heavy lifting as the actual crash is obscured, imagery reliant on the audience’s imagination and thusly making the crash feel even more violent. Thus, we are greeted with a shot of the cat drumming its fingers in impatient contempt. Informative, but tiresome when the shot stretches on for nearly 10 seconds—about 6 seconds too many.

Clampett indeed pulls out all the stops in the name of conservation. Opening disclaimers, long camera pans, repeated shots of animation, long pauses… these trends continue on strong for at least half the cartoon. Again, as has been harped on in previous reviews, it’s not very likely audiences would have grasped such cheats so quickly at that point in time. The effects of the Depression were very much still lingering. Regardless, such economic trickery wasn’t utilized in such heavy concentration by the other directors at the same time. It is easy to criticize when knowing how Clampett’s filmography has blossomed previously and will blossom again in the future, but such criticisms are not entirely without merit.

A transitionary time card introduces a purposefully unnecessary formality in both its purpose and wording. Evoking comparisons to similar transitions in a silent film, the sophistication (such as “shop” billed as “Shoppe”, a surefire emblem of highbrow establishment) comes as a deliberate incongruity to the unsophistication that are cat and mouse chase cartoons. Similar transition devices would be utilized in The Sour Puss, whose eponymous cat is essentially identical to the one seen here.

“You, You Darlin’” provides easy listening on top of another slew of establishing shots and sign gags. Tubby Millar’s “Under New Mis-Management” gag from Ali-Baba Bound makes a return with the introduction of Porky’s pet store specializing in fish, while puns on a handful of signs in the window display foreshadow the remaining 5 minutes of the cartoons. Lots and lots of fish puns. Fish puns debatable in their quality and ingenuity.

As the camera dissolves and trucks into the interior of the shop, leftovers from Porky’s Last Stand can be found in background details; like the former, a calendar on a row of shelves forecasts the ominous date of the 13th. Such an ominous date unfortunately doesn’t bear as much weight in this short as it did in the former thanks to weak directing and a very domestic, piddling premise. The real bout of bad luck lies in the barrage of half-baked fish puns to follow.

A comedically wooden shot of Porky standing vacantly in the middle of his equally vacant store provides a segue into a synonymously wooden song number. Or, at the very least, as wooden as starting a song with “I am Porky the Pig” can be—which is to say quite a bit.

All throughout the cartoon, he suffers from vapid voice direction; not necessarily the fault of Blanc, but uninspired scripts that don’t seek to work to the character’s strengths and vice versa. Instead, his introduction of a number outfitted to “Oh, Dear! What Can the Matter Be?” is mildly obnoxious—not to a degree of charismatic endearment, as seen in Porky’s Last Stand, but a sort of grating nerve reflected by the loose attempt to rhyme “fishes” with “pig”. Outside of a strong line of action and clear silhouette with his bowing pose, the animation drawings of Porky himself are likewise not especially attractive. A brief John Carey shot of Porky shaking his hips to a beat that is not reflected entirely in the music—it seems to beckon a percussive timpani accompaniment that is not there—attempts to somewhat rectify the looseness of the prior scene. However, camera registry issues with blurriness and being anchored to the previous pose to maintain consistency don’t provide many favors.

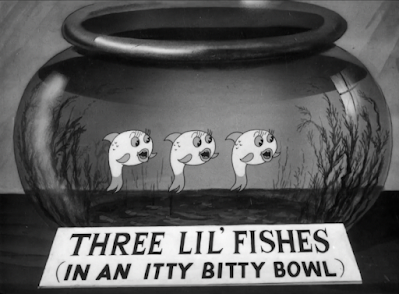

Thankfully, The Rhythmettes pick up the slack through their saccharine harmonies, attempting to breathe what little life they can into the pedestrian slew of fish puns more novel 82 years ago than they are now. Already, such wordplay can be seen through the sign positioned neatly outside their bowl. Such serves as a nod to Kay Kyser’s hit “Three Little Fishies (In an Itty Bitty Pool).” As for the bowl itself, the aforementioned attention to detail with background paintings—particularly glassware—come into beautiful effect. Even the plants on the inside of the bowl are warped in their perspective to seem more realistic, lifelike, dynamic. A certifiably refreshing attention to detail to a cartoon in need of such incentives.

A majority of the fish puns, if not all of them, are thankfully innocent. It’s certainly easy to become hard-boiled after decades and decades of exposure to such puns in a similar vein, whereas these sight gags and jokes still held quite a bit of novelty at their time of conception. With the exception of the “holey mackerel”, his sculpted and antithetically detailed appearance almost rendering him an escapee from Fresh Fish rather than of true Clampett creation, the fish in the song number boast some functionality. Electric eels release their charge in tandem with the music, the perch whistles like a bird to the musical accompaniment…

…and, in perhaps the most impressive beat of all, sole are rendered into their literal counterparts, transforming into a pair of tap shoes that jive with a portion of the music dedicated exclusively to its presence. Even if much of the animation thrives on a cycle, carried more through sound rather than intricate motion, it’s a welcome subversion that does possess some vestiges of ingenuity. Or, at the very least, thought.

Especially compared with the blatant reuse of a strip teasing octopus from Porky’s Five & Ten, a much more chipper and lively entry in spite of its more primitive design sense. Reusing the octopus necessarily isn’t an issue, but rather the integration—with the animation directly reused from the aforementioned cartoon, it feels as though the octopus is dancing in a spontaneous underwater void rather than confined to a fish tank. So much as a subtle painted overlay of a white line meant to convey the reflection of glass would bridge the connection more smoothly; the curtains meant to lure the audience into thinking it’s a series of human legs could still be placed on the outside of the tank, strategically concealing any or all instances of an aquatic confinement. Such is not the case.

That we are given a somewhat extended beat delegated to showing Porky leaving the cartoon as conspicuously and plainly as humanly possible very clearly indicates Clampett’s state of exhaustion with the character. We have gotten to the point where leaving the short is a plot point in itself.

Lunch breaks manifest as the excuse in question—instead of a regular whistle sound, Blanc’s manly, windy bellow of “LUUUUUUUUUUNCH!” erupts instead courtesy of the whistle’s decidedly human mouth. Slanted, diagonal angles of the shot and generally tight composition encourage dynamism and visual appeal. At least, all that can be gathered from a brief shot of a whistle.

It’s certainly more dynamic than Porky’s exit, who is burdened yet again by vague, melting animation and wooden dialogue. A majority of Porky’s animation appears to be the presumable work of Dave Hoffman, who receives the animation credit. While pure speculation, the pinched mouths, outstretched hands, somewhat incongruous attention to detail with the finger placement and thick pupils seem to have only appeared after the departure of Bobe Cannon from Clampett’s unit, who Hoffman appears to have replaced.

Blanc does what he can with the writing; the voice direction is nowhere near as abysmal as anything found in a Hardaway-Dalton Porky cartoon, but his very conspicuous quip of “Lih-lih-lunchtime! Buh-be-boy, when it comes to eatin’, I’m a rih-rih-regular little pig!” feels oxymoronically self aware and not self aware enough, forced rather than charismatic. Clampett would thankfully redeem himself through the otherwise irredeemable Patient Porky, where Porky’s “I made a pig of myself” pun is a more naturalistic concession rather than a transparently desperate attempt to get laughs.

Camera registry issues with blurriness and more unappealing drawings—particularly the squint as Porky hobbles away and whistles, reading as uncanny rather than jovial—seldom add a benefit. Stalling threads the entire sequence together through more chipper orchestrations of “You, You Darlin’”, and the overzealousness in which Porky tosses the “OUT TO LUNCH” sign on the door hook inflates the cartoon with desperately needed pep. Regardless, Porky’s exit is ironically so concerned about ensuring he's out of the picture that takes up twice the amount than what is necessary. The cartoon is over halfway through at this point, and very, very little has happened.

Thankfully, the reappearance of a now downtrodden, mouse-less cat seeks to change that. The goldfish positioned conveniently in the store window serves as the next best substitute for mouse—but not before a series of somewhat discombobulated camera movements. A truck-in and cross dissolve to the cat pacing up the sidewalk works, mainly to adjust the staging in accommodation with his height, but does admittedly contribute to a reigning restlessness as the camera makes an arbitrary jump cut shortly after.

Likewise, the camera begins to pan up upon the cat’s surprised take; the scene shifts upwards as soon as his butt hits the ground. An attempt to make his take feel more kinetic and surprising somewhat backfires given that the cat still moves after the fact. Instead, he appears to glide across the ground, sliding forward as the camera pans upwards, making for a rather messy end result. Especially when paired with the jump cut after to the camera zoomed in an inch or so—there is no discernible difference or improvement in clarity, even when the cat uses the space to stand on his hind legs and press his face against the window.

The close-up shot that follows nevertheless brings relief through much more coherent and careful composition. Glass splits the screen in two, naturally segmenting the characters and forming a subconscious divide adopted into the mindset of the audience—predator versus prey. Even then, the window is partially angled, giving the fish more negative space so as to encourage a more naturalistic split in the screen. Obscuring the perspective and just having a gray line down the screen with no elaboration would make the scene feel too flat. Such is not an artistic goal.

John Carey’s enigmatically appealing and sculpted animation of the cat humming in unbridled ecstasy “Mmmmmmmm-MM!”) would be reused again in The Sour Puss with no discernible design changes; the cat would also have a much broader range for more acting opportunities than what is presented here.

Even then, he’s very much the star of the show in both cartoons—a notion unmistakably established once he sneaks into the pet shop. While his exchanging of the “OUT TO LUNCH” sign for an “IN TO LUNCH” sign is somewhat unnecessary, it is mainly hindered through slow pacing rather than a bad idea. A pause spawned by the slam of the door proves its own merit as well—a subtle but very well executed camera shake births an added weight to the cat’s presence and motions. Crashing of cymbals in the musical accompaniment is timed to the slam of the door, encouraging the kinetics of the effect. All is not lost despite the somewhat meandering pacing.

Constructed, weighted, organic animation drawings from John Carey continue to enrich the viewer in a cartoon that is as far removed from the description “enriching” as possible. Acting on the cat is keenly informative in his aloof slyness, disingenuous humming to indicate feigned nonchalance as he peruses his waterlogged buffet. All is made effective through Carey’s animated subtleties. A flick of the wrist, a bend of the head, an amiable hand on a popped hip as he pulls up his fur sleeve and traverses the confined waters. Carey’s appeal and eye for intricacy is always appreciated, but in a cartoon so relatively ugly thus far, it’s a catharsis.

Hints of the more unabashedly juvenile (to a strength) Porky’s Five & Ten are delivered through the courtesy of a close-up. Whereas a sardine in the former murmurs garbled prayers in the midst of a climax before retreating in its sardine tin, here, an oyster seeks refuge in an appropriately labeled oyster bed. Comparatively, the animation is much more elaborate (regarding both design sense and motion), but lacks the spontaneity of the former. Perhaps some of that is owed to the perspicuousness of the labeling—the sardine bed metaphor was carried more through its appearance and the sardine praying at the foot at it rather than such clear labeling.

Following a repeated shot of Carey’s cat still rummaging through the fish tank, his clawed hands now have their sights set on one of the female choristers (who has magically relocated bowls.) Sure enough, his successful capture of the fish renders the cartoon somewhat archaic beyond reused fish gags. Unmistakably feminine features on the fish may to be blame—regardless, the “villain kidnapping a helpless, dainty, damsel in distress” harkens back to the earliest cartoons of the ‘30s. This is especially true of Warner’s legacy, where every other cartoon for an extended period of time followed this same formula. Granted, Clampettian subversions are to be expected… even if those subversions lose their touch after having been exposed to the viewer in prior cartoons. The cat’s expression of visceral grotesqueness provides reassurance in that this is no Harman and Ising cartoon.

Nevertheless, the electric eels showcased in the song number assert that they are more than mere decoration—rather, they provide a warning to their fellow encapsulated denizens. Forming the words “The Cat” with their bodies is whimsical in itself, construction basic but motion and spirit smooth. However, a step is taken further to have their electric charge serve doubly as a means of Morse code.

Ample opportunity for cinematic staging is thusly granted. Composition is clear, and the viewer’s eye doesn’t feel as though it’s interlocked in a battle of clarity between the electric eels in the background and the silhouette of a seahorse and turtle in the foreground. A keen eye for coloring and value plays a great part; the white glow of the eels serves a solid juxtaposition between the black, opaque tones of the foreground characters. Likewise, Dick Thomas’ elaborate background paintings framing the characters naturally attract the eye towards the subjects rather than getting lost in the lushness of the background. A tangible attention to detail that could stand to be distributed to more lacking aspects of the film.

Selection of a seahorse and turtle to witness the spectacle are not as random as they appear on the surface. Instead, they pave the way for an allusion to Paul Reverse, the turtle shrieking a high-pitched call to arms against the cat. Staging is striking, particularly through opaque coloring on the subjects and background flora juxtaposed with the glow of the paint itself.

Swimming cycles on both characters are serviceable in their consistent, solid momentum maintained through an ongoing camera pan; the effect almost seems lost when the characters are briefly shed in visible light, cinematics abandoned in favor of a traffic gag not incomparable to the directorial sensibilities of Tex Avery.

Speaking of Avery, Clampett heavily references his tuna from Fresh Fish to fashion it for his own story demands. Thanks to the clarity of the film, the line between cel layers (that is, the stagnation of the tuna’s body and the layer for its head) is visible. It comes as somewhat uncanny, given that it disappears to accommodate for the fish’s full body convulsions spurred on by its chicken clucks.

Regardless, the tuna isn’t a means of pun delivery so much as it is to propel the plot forward. Clampett’s artistic identity somewhat grips itself around the fish upon its eye take. Likewise with it laying eggs—“artistic identity” applies to refurbishing of footage from What Price Porky and Naughty Neighbors. Similar to Neighbors, the marching fish are somewhat discordant in their trapping thanks to the discrepancy between planes: a horizontal background pan with 3/4ths perspective in motion.

Repeated cutting back to the tortoise Revere seeks to provide a bridge between scenes. It works in that it elevates his repeated calls to arms outside of aimless dialogue, attaching a—albeit concealed—face to the voice and the action. Regardless, technical issues persist between juggling the horizontal camera pan and the vertical truck-in of the camera; the pan halts for a few brief frames, wedging a jolt into the rhythm of the shot and losing its intent. Thankfully the shot is short, a mere bridge rather than elongated highlight, but maintaining consistency is the main job a bridge seeks to accomplish.

A spotlight is now shed on a flock of flying fish. Whereas the flying fish seen in Pilgrim Porky lived up to their namesake through the courtesy of miniature, fish-sized airplanes, the fish here are the planes. Such a gag would be repeated heavily throughout The Sour Puss, where an elusive, screwball fish uses its flying anatomy to its advantage. Clampett and company get fancy with the camera movements, the camera panning in a smooth diagonal glide that matches the gradual ascent of the fish. Focus issues prompt the establishing shot to be shrouded in low resolution, blurriness persisting once again, but that thankfully rectifies itself once the camera gets moving.

Grotesque appearance of the cat sneering at his fish prey is as accidental as it is purposeful. Adjoining drawings of the cat lean more on the ugly side—features are somewhat vague, melty, mushy. Then again, the tightness and control of Carey’s acting in the previous fish scenes set an unfair precedent in terms of their own quality. Regardless, ambiguity of the drawings and their construction in aiding the cat’s intended viciousness, particularly on the first shot where he looms over his meal. Eye direction is off and his features feel flat, though the off-kilter appearance helps more than hinders. Acting on the cat as he sneaks some furtive glances—particularly the tail jolting straight up—is a welcome addition.

Further ties to Fresh Fish are established through the utilization of a literal hammerhead shark. Clampett’s take on the creature is unsurprisingly much more compact, cute, mischievous versus Avery’s much more realistic and grounded take.

His hammer head is put to good use. Reverberations on the cat’s head as he withstands the blow are mild, somewhat exaggerated through the restlessness of the camera as it pans to the right in an attempt to fit the cat in the scene. Fidgety camera movements are rife throughout not only that scene, but the cartoon in general.

Another shot of the cat anxiously peering around after a glimpse of the impending flying fish assert this. To Clampett’s defense, the movements of the camera seek to evoke an added anxiety, indicating the cat’s nerves at being cornered by a gang of fish. Emotions of the cat are shared vicariously through the audience in that regard, and are certainly effective, but nevertheless arrive as a distraction. Perhaps that comes from the scene following an overhead shot of the flying fish who are victim to the same camera zeal. An attempt to make the filmmaking seem more invigorating and captive instead reads as busy and unfocused rather than climactic—if the action on screen were truly exhilarating, such technological Band-Aids would not be necessary.

Nevertheless, dramatic upward angles of the cat backing into the electric eel tank feel more methodical and authentic in their drive to convey dynamism. Likewise with the cat sticking his tail in the air; while that action reads as somewhat more stilted and forced, seeking to provide a bridge to the impending gag, it’s nevertheless elevated through a focused line of action.

The inevitable aftermath comes as one of the short’s most appealing snapshots; force of the shock is so strong that the cat completely jumps out of screen in a violent overshoot, just to return back to its place by entering through the bottom corner.

Completely shrouding the composition in darkness—the background replaced by a dark color card with streaks of paint to indicate vague definition—likewise direct the audience to the action and nothing but the action, electric charge completely dominating. With the giant overshoot, the dark background, and wide staging as a whole, the electrocution feels all the more visceral and earned in its appearance. Out of all of the gags and beats touted by the short so far, this is really the only one that seems to have any sort of metaphorical gravity and weight behind its use. If only for this moment, the stakes do seem high.

Unfortunately, that sort of spontaneity disperses as quickly as it was spurred on; the succeeding shot of the fish being jolted out of the cat’s hands suffers from its mechanicality. It appears as though the fish levitates upwards out of the cat’s clutches rather than slipping out—the cat’s paw itself lacking a throwing motion clinches this. While it’s mainly a staging maneuver, the fish flying up much more clear than slipping out from under the hand, it nevertheless comes as a hindrance when paired with the anomalous organicism in the animation of the cat getting electrocuted.

A rescue is nonetheless executed courtesy of a flying fish. Demonstrating the flying fish catch the victim through the courtesy of silhouettes does aid in rendering the dramatics more extravagant, but not much else. Perhaps some of that comes from a slew of Clampett cartoons that precede this with similar climaxes; Chicken Jitters and Wise Quacks come to mind, and that’s speaking purely in terms of Clampett rather than the entirety of the Warner filmography.

Shoddy filmmaking, moreover, does little to excite the audience. Quality vary in terms of how well the shots flow together—Clampett’s cutting is on the more frenetic side in this case, but to a bit of a detriment. Poses don’t always hook-up, causing a natural jump; the little fish positioned perfectly on the flying fish after being rescued comes as a particularly succinct example of such. Some shots are held on for too long, others too short, the variations having a tendency to feel like slapdash filmmaking rather than a deliberate attempt to vary pacing (though that in itself can be felt through parts of the climax.)

Regardless, the climax does approach its end as the jolt of the still electrified cat sends it rocketing across the screen and into a spare fish tank. Brief reprisals of the cat’s electric convulsions are shot on a double exposure in an attempt to create an after-image effect; it’s brief, almost reading as an error, but is nevertheless effective in creating a frenetic blur of motion. Propelling the cat diagonally across the screen in perspective rather than horizontally seeks to embrace additional depth of surroundings as well.

Focus issues with the camera persist in the cat’s finishing blow. A shame, as the Popeye allusion with the mussel is one of the sight gags offered by the cartoon that has more merit to it. Perhaps part of that comes from a genuine appreciation of the source material—Clampett’s animation style persists in a scene from Tex Avery’s Porky’s Garden where a chick devours some spinach and turns into the aforementioned sailor, whereas Clampett’s own Porky’s Hero Agency has a statue reuniting with her own decidedly Popeye-shaped forearms. Though muddled by the blur, a plethora of brush trails and impact lines rightfully breathe energy into the energetic-by-nature wallop.

Thus provides the perfect opportunity for an ever shoehorned Porky to return from his lunch break. Just as he opens the door, the cat is propelled violently from the premises--Porky is thusly caught in the wake of the breeze, Treg Brown’s wind whistling sound effects supporting the ferocity greatly.

“Whew!” As the camera somewhat needlessly trucks into Porky, focus is skewed yet again. “Wih-wih-what a draft!” Phoned in as the vocal direction may be (or his appearance as a whole), Clampett’s continued embrace of Porky as an utterly oblivious innocent continues to be endearing.

Bookends are rife throughout the cartoon’s end, whether it be through Porky’s appearance, the cat drumming its fingers in disgruntled concession, or the familiar whistling of “The Girl with the Pigtails in Her Hair” offscreen. Attempts to somewhat disguise the reuse of the cat’s finger drumming manifest through his newly mud soaked appearance; the same cycle would, ironically enough, find its way back in The Sour Puss.

Appearance of the mouse is futile from a story front. Despite that, he does maintain one purpose—to bring the cartoon to its end. Following some particularly unappealing drawings of the cat stalking it’s victim (and a brief cel error on the mouse jumping into the wrong position), he reciprocates the cat’s menacing growls with ease, line of action and silhouettes strong on an otherwise vague and undefined drawing.

The cat is therefore put right in its place. A take off of a gag used to perhaps a more striking effect in Inj*n Trouble, Clampett would yet again would bring a reprise to a much more comedic degree in Goofy Groceries a year later. Regardless, vague as the drawings may be here, the line of action on the mouse is potent, as is his self-satisfied resuming of joyous humming.

Though I’m certain some of my wording alluded to my opinions on the short more than once, Porky’s Poor Fish is not a film I hold near and dear to my heart. Rather, I would say it’s one of my least favorites in Clampett’s filmography—at the very least, it certainly feels like one of his weakest.

It virtually takes more than half the cartoon for anything of significance to happen. The crux of the story and climax as a whole are only intriguing through brief spurts, shots flow together poorly, what little voice direction present is uninspired at best, the animation is on the uglier side more often than not. Admittedly, a lack of interest with most of the gags come from hindsight bias—or, more accurately, foresight bias. An electric eel blinking in time to music was much more novel in 1940 than it is now. It does seem somewhat unfair to judge a slew of jokes for being repetitive when taking other years of cartoons into effect, both past and future, but the manner in which they’re deployed certainly does beg some added inspiration. Many of the sight gags are executed at face value or overly conspicuous in their delivery.

Porky’s relevance—or lack thereof—in the story is sad more than anything. I don’t fully believe Clampett’s exhaustion solely lies with Porky as a character so much as the obligation to throw him in every cartoon did. Making his exit a plot point in the cartoon isn’t necessarily a commentary on his character or how obtrusive he is—someone like Frank Tashlin was much more vocal about his disdain for the character, which is visible in his cartoons; Porky’s Romance for one—but a clear indication that Clampett is worn down by his obligations and doing everything he can to work around them. It’s certainly understandable, as having to sacrifice story ideas for the sake of making sure the pig gets a line in or two will obviously put a damper on the focus of the short.

Regardless, I believe this point in time is Clampett’s weakest time period as a director. A director who capitalizes on emotions from the characters, audience, and even animators alike, it is incredibly easy to grasp whether he’s interested in a cartoon or not. Outside of a few exceptions—such as the cat getting electrocuted—Porky’s Poor Fish does not feel like a cartoon made by a group of people having fun. It feels forced, tired, trite, a means to reach a quota and nothing more.

As big of a Clampett fan as I am myself, this is one of a handful of cartoons of his that left me feeling thoroughly annoyed upon watching it, Chicken Jitters and Porky’s Hotel being a few others thus far. He would eventually see a rebound—particularly upon the acquisition of Tex Avery’s unit—but, unfortunately for us, that isn’t for some time yet.

.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment