Release Date: April 13th, 1940

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Tex Avery

Story: Ben Hardaway

Animation: Rod Scribner

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Robert C. Bruce (Narrator), Tex Avery (Papa Bear), Sara Berner (Mama Bear, Little Red Riding Hood), Berneice Hansell (Goldilocks, Baby Bear), Mel Blanc (Wolf)

(You may view the short here or on HBO Max!)With travelogues keeping him occupied, Tex Avery hasn’t had much time to lean into his liking for fairytale parodies—until now. After a near two year absence between such burlesques, he would begin to lean into the genre a little more frequently; his next film after this, A Gander at Mother Goose, is a nursery rhyme and fairytale themed spot-gag cartoon. Likewise, his tenure at MGM would allow him to indulge in the fairytale format more frequently.

The Bear’s Tale serves as a loose, very informal precursor to Chuck Jones’ shorts centered on The Three Bears; the main connection is the burlesque of the same fairytale, but are both executed with a palpable wryness and certain dysfunction that purposefully subvert the domesticity of the original story. Such cynicism applies more to Jones than it does Avery, but Avery nevertheless embraces subversion as tightly as he can. That’s what this short is all about.

A meeting of the minds, The Bear’s Tale combines both the story of The Three Bears and Little Red Riding Hood through a self aware, indisputably Averyesque cast of characters.

Worth noting is Ben Hardaway’s story credit—while shorts were typically constructed through a “jam session”, often involving the input of multiple writers at a time rather than one single gag man (at least until the next year or so, when writers typically were attached to one single director.) It seems much more plausible that Hardaway was a victim of the rotating credit system rather than him actually writing the short; the calmness, sardonicism, self awareness, and general cleverness is not in Hardaway’s nature. There are no indications in the writing of his input—the short is much more successful as a result.

On the topic of the title credits—or, more specifically, design of said credits—the title card doesn’t immediately register as a book cover until the book actually opens. Avery used a live action storybook opening with Little Red Walking Wood, but was more apparent in its status through the texturing on the cover. In a way, the surprise of the opening fits the presiding theme of subversion touted by the cartoon to begin with.

Nods to Hollywood and its prestige seek to inform the viewer of the short’s tone. Renowned director Mervyn LeRoy is lampooned as Mervin LeBoy, receiving a shoutout for providing the services of one “Miss Goldilocks”, “Miss” adding its own playful haughtiness. Musical theming and association is employed more heavily in this cartoon than others; thus, a muted yet saccharine arrangement of “You Oughta be in Pictures” is the only logical source of accompaniment.

Unlike Avery’s previous fairytale burlesques, he employs the use of a narrator—the ever reliable Robert C. Bruce. Such a choice exercises a certain level of control (and faithfulness to the genre in which Avery is lampooning) that wasn’t present in the more spontaneous, free-for-all character driven stories of Little Red Walking Hood or Cinderella Meets Fella. While having a narrator enact clichés seems hindering, Avery has worked with Bruce enough times to know how to strategize his input. Bruce serves more as a device to provide wry bits of continuity rather than actively carry the story; the characters and Avery’s direction do most of the heavy lifting.

Indeed, much of the cartoon runs on a start and stop format. Bruce says a line, and a beat will interrupt momentum through a corresponding music sting before marching forth and repeating. For example, his introduction of “Once upon a time, long, long ago…” is followed by a brief musical interlude of the ever appropriate “Long, Long Ago.” Said interludes are brief, intended to establish a somewhat off-kilter rhythm that represents the short’s own off-kilter premise and attitude.

To cement the idyllic and certifiably unmistakable fairytale atmosphere, Avery asserts a menagerie of clichés, particularly through background shots. Presence of a castle in the book serves as pure irony and nothing more, a mere vessel of association—no castles are involved with nor necessary in the story of the Three Bears. Likewise, the setting being “long, long ago” is another purposefully transparent cliché—modern conveniences and appliances are liberally applied later in the cartoon to further the story. These details are not holes in the story, but purposefully loose and ironic attempts to set the scene through recognition.

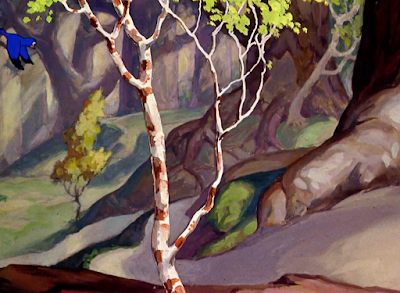

Focus is therefore delegated to the story’s surroundings—ones that are actually genuine in their appearance. 20 seconds and change are therefore delegated to a faux-multi plane pan of the forest, shrapnels of animation provided through the cloying yet atmospheric weaving of birds through the trees. General visuals and color schemes of the forestry are not entirely unreminiscent of the lush forestry touted in the ever impending A Wild Hare. Bruce’s narration on the self-described beautiful green forest is accompanied by a fitting snatch of Mendelssohn’s “Spring Song”; for all of the scene’s cloying intentions, the result is rightfully striking.

A keen understanding of figure ground composition contributes greatly to the success of the visuals. Most apparent in the composition is the frame around the bear’s house constructed by a few birch trees; while conspicuous enough to guide the audience’s eye and assert a somewhat sardonic notion of peace and saccharinity, the frame still maintains its naturalism. It doesn’t feel forced nor mechanical in its construction. Appearance of the cottage begs, of course, a rightful musical sting of “Home, Sweet Home”.

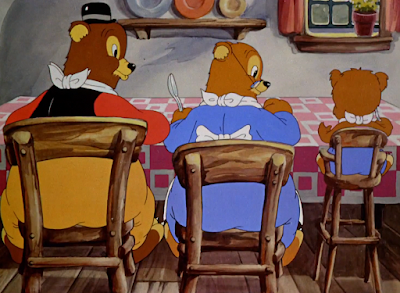

Instead of dissolving to a quaint image of a bear family so sentimental and coy that even Norman Rockwell would be averse to, Avery literally throws the stars right into the picture. Tossing them in from the sides and the foreground—as opposed to them just dropping from the sky—further integrates the audience in the picture through immersive perspective. Likewise, a clever sardonic commentary weaves itself by having the bears completely and deliberately facing away from the camera. Partly to maintain suspense (if one would call it that) for the reveal. Partly to introduce an informal yet comedic rudeness at the characters seemingly ignoring their viewers with their backs turned.

A cross dissolve to the other end of the table serves as a formal introduction instead. “The Papa Bear…”

Bob McKimson is succinctly cast to establish the personalities of the characters. Even despite the commanding sense of false authority garnered by the following music sting of “What’s the Matter with Father?”, McKimson thoroughly asserts Papa’s nonchalant smugness through facial expressions, posing, and acting alone. Mannerisms such as the hat flick or walking his fingers across the table seem to evoke the imagery of Oliver Hardy.

Mama’s introduction is synonymous in its clarity; a snatch of “That Wonderful Mother of Mine” is successfully disingenuous when juxtaposed with her domineering glare towards her husband—Avery jumped at every chance to incorporate stereotypes of battle axe wives in his cartoons.

Baby Bear’s introduction is the simplest, but just as striking and humorous in its character animation. The audience is fortune to be privy to such an engaging, thought provoking spectacle as his mindless gnawing on a spoon, infantilism exaggerated through a polite score of “Rock-a-Bye Baby”. McKimson captures the aimless baby motions perfectly.

Adoption of McKimson (and Rod Scribner, who provides his wealth of appeal and life in his scenes to come) bestowed a newfound sophistication in both design and motion to Avery’s cartoons. Avery had a tendency to be dismissive of the artistic quality in his cartoons—not against the animators, but himself, claiming that he was much more of a gagman than an artist. While certain instances of crude simplicity or generally uncanny design—for example, the brief period where proto-Fudd’s eyes were more open, features somewhat more defined and making for a very odd disconnect, especially compared to his streamlined origins—could be found in his shorts, they were never a major detractor from the spirit and tone of the cartoons at hand. Regardless, gaining access to two of the best animators at the studio opened a wide door of possibility and nuance that hadn’t been approached by Avery before. It’s certainly hard to imagine the likes of A Wild Hare without the sheer sophistication or brilliance of Bob McKimson’s animation. Indeed, such growth can immediately be spotted upon the introduction of the three bears here, whose differences in personality all serve as a form of structure in itself.

To establish and sustain rhythm, the entirety of the introduction follows the same cadence, camera locked only in a pan sliding back and forth between characters. From Papa, to Mama, to Baby, back to Papa, to Mama, to Baby, from Baby, to Mama, to Papa, and so forth. Audiences are enabled to digest the format easily, whose repetition reads as a joke in itself—especially with the purposefully stilted and extracted timing touted all through the cartoon. Simple staging, yet very effective recognizability and momentum.

Incorporation of porridge thusly follows the same rhythm and ethereal entry.

Baby is the first to complain about the porridge’s heat; while Berneice Hansell’s heyday has begun to pass in favor of more versatile female roles that weren’t just “squeaky voice”, Avery nevertheless utilizes her high pitch masterfully. Her helium “Gee, this stuff’s too hot!” grates the audience’s nerves just as much as it fits the bill.

Sara Berner’s delivery on the mother (practically sounding identical to Elvia Allman, who was an Avery regular just a few years prior) appeals to the aforementioned strife for versatility as she channels the deliveries of a scratchy, hysterical grandmother rather than gentle mother. An arbitrary overzealousness in her deliveries—such as the “WOO-OOH!” after burning her tongue and dropping her spoon with a most conspicuous clatter—cements Avery’s establishment of the bears feeling more like actors thrown into their parts rather than a natural retelling of the story. Why else would such hamminess be necessary?

On that thought, Avery continues to disestablish any notions of sincere storytelling through Papa’s appearance. Baby complains about the hot porridge, Mama complains about the hot porridge, and Papa…

Papa belly laughs off the complaints of his family in a gorgeous display of exuberant inconsideration. With Avery providing the vocals of the Papa Bear himself, there is a strong comedic potential found in the disconnect between Papa’s simple-minded, oblivious conceit and the sheer sincerity of his laughter. He isn’t necessarily laughing at them to be an ass or ridicule him—it’s just what he knows, one of life’s pleasures, truly aspirational in his unapologetically blissful ignorance.

McKimson yet again manages to capture a great number of intricacies that make Papa’s performance feel more whole and personal, whether it be a solid, anchored tilt of the head forward or more obvious like the somewhat condescending head waggles as he politely sneers “Soup’s too hot.” His joy is perfectly reflected in the animation, particularly on the bout of laughter before he indulges himself.

Avery purposefully betrays the audience’s expectations and almost makes them feel bad for doubting Papa’s dismissal, as he manages to consume two spoonfuls of the porridge without flinching or missing a beat. Perhaps there is something to his simple ways that we aren’t grasping. Perhaps Baby and Mama are just overreacting… as, of course, babies and mamas do. At least according to smug papa bears.

Nope. A halt and drooping of the face as Papa stares vacantly at the viewer paints a picture of regret just as much as it does realization. Completely halting the music score for a second, allowing only the sickeningly hot gurgles of porridge to fill the air succinctly exaggerates the blazing heat of the food, which, in turn, exaggerates Papa’s turmoil.

A frantic clapping of the hand to the mouth and steam pouring out of his ears validates the protests of the remaining Bear family, as well as share a laugh at the audience for momentarily tricking them. We approach Papa thinking he will immediately be bested by his words, then are surprised to see him actually consuming it with no indication of any trouble… until our initial suspicions are validated at the last second. Expert comedic and behavioral timing as always.

Likewise with the “resolution”—a gag in sheep’s clothing. Papa rushes immediately over to the sink to guzzle some water; Avery cleverly conceals any indication of the physical water itself, consumption sold only through the animation and somewhat grotesque sound of Papa’s gulping.

With equal ferocity, more steam billows out of his ears as he yet again clasps a hand to his face.

Instead of indicating that the tap was for hot water from the start (making the punchline too obvious by telegraphing what’s going to happen, causing it to lose its impact), Avery enacts a fascinatingly kinetic and immersive zoom-in onto the “HOT” label that is present only in a close-up. Papa turns his head as the zoom occurs with a solid consciousness and meticulousness in the art direction—such a maneuver tricks the eye into thinking the zoom is actually rotating into place. In reality, it’s only a simple cut-in, but the promptness of speed and care in the setup effectively turn it into something more.

Avery makes an important point to asset that Papa isn’t hurt. In fact, he laughs it off, completely smitten with his purposefully lame snark of “Hot stuff,” enamored yet again by the simplest pleasures in life. Asserting that the characters are okay—stunned, but okay—encourages the audience to laugh and not feel put off by any potential violence on-screen. It’s not necessarily an act of keeping it clean so much as it is maintaining the audience’s attention and pacing of the cartoon. Wholly unapologetic, joyously mean spirited slapstick is reserved more for villains and antagonists, which Papa is not. Instead, the sheer amount of time he spends guffawing at his own stupid joke seems to trick the audience into thinking it is funny thanks to the sincerity in his vocals.

Mama remains unaffected by the display and allows Papa to indulge in his own simple fantasy. Bruce revives his narration to follow Mama getting ready for their script mandated walk in the woods—a snatch of “Put On Your Old Gray Bonnet” plays accordingly.

Turning the mirror around to admire her back view feels like a vignette adapted right out of a comic strip or silent film. Simple, deliberately stupid, but casually so. Unobtrusive sparkle effects of the light reflecting from the mirror reassure the audience that yes, this is indeed a real mirror.

Visual gags involving doors was another Avery trademark. While a more polite example compared to some of his other door gags, the sheer functionality of a 3-in-1 door perfectly tailored to the builds of each bear is certainly amusing through its convenience.

“And into the beautiful green forest…” The same establishing pan—albeit reversed—and same sting of “Spring Song” continue to glue a solid, rhythmic, identifiable momentum and foundation.

“…rode the three bears.” A three way tandem bicycle pokes even more fun at the convenient appliances owned by the Bear family. Such conveys a purposefully disingenuous sense of togetherness, an mandated obligation rather than an earnest investment for some joyous family merriment.

Papa pompously throwing his feet up on the handle bars is followed by yet another snatch of “What’s the Matter with Father?”…

Mama does the same, company provided by “That Wonderful Mother of Mine”…

…and Baby Bear is a victim of comedic subversion through the rule of threes. Quite effectively, too, as the rhythm of the cartoon is so deliberately entrancing that the reveal of Baby struggling to keep up the pace comes as a genuine yet satisfying surprise. A surprise that isn’t even much of a surprise—if anything, it being so rooted in logic is what makes it funnier. The bike has to maintain momentum somehow. Both the pained expression on the tot and fervent cycling as his animation is timed on ones actively make his toil more visceral and sympathetic, not to mention funny.

“Meanwhile, through the beautiful green forest…”

While the layout of the forest is somewhat different than other pans, sardonic retainment to the shtick and repetition is cemented through another purposefully quick sting of “Spring Song”, continuity cemented by another cameo of contented songbirds. The pan, the music, and the birds are all timed to be more abrupt and curt—the audience understands the shtick by now. Pacing repeated bits of action quickly seeks to provide a coy refresher and little else; there is no need for another extended, 20 second long pan when that has already been established. Avery was truly skilled at maintaining the audience’s attention, and testing it only when it was most necessary. That is, only when it was most funny.

“…came little Goldilocks.”

Enter that little peroxide blonde, skipping to a fluid, weighted, and wonderfully cloying walk cycle. Her theme song is an accompaniment of “A Tisket, A Tasket”, artifice dripping from the whiny, sliding strings.

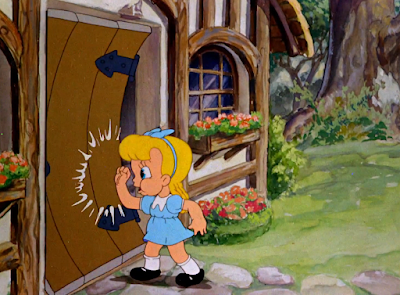

“Suddenly she stopped…”

“…and there was a house.” More start-n-stop momentum occurs in terms of both musical obligation—another curt sting of “Home Sweet Home” short enough to get the point across—and strategic placement of shots. Rather than having Goldie stop right where the house is visible, the camera halts for a second, pans, then sheds a brief spotlight on the abode in question. Such deliberate un synchronization ironically establishes its own solid and digestible rhythm.

“A Tisket, A Tasket” likewise grows in speed and curtness as Goldie approaches the cottage, Avery’s penchant for summarization solid as ever.

“She knocked on the door…”

Polite flicks of the wrist juxtapose with the violent convulsion and slams as the door is knocked repeatedly out of its hinges. A very slight disconnect in terms of weight between the hand and the door is apparent, but doesn’t come as much of a detriment seeing as that’s the entire purpose of the gag. A cut to the interior of the house strengthens the ferocity without the disconnect present; the intent remains no less intact.

Thus initiates the short taking a more subversive, decidedly Averyesque turn in storytelling. Already, Avery has cleverly strung enough context clues to build-up to the reveal—the house is referred to as a house, not a cottage, it’s on the opposite side of the forest, the exterior looks different, as does the interior. Nevertheless, a camera pan scanning the house’s inside expertly timed to a foreboding snatch of “Mysterious Mose” cements that trouble is afoot. Such nefarious music and anxious camera motions surely aren’t fostered by the forced domesticity of the Bear family.

Such attitudes in filmmaking are reserved for the wolf. That is, the wolf from Little Red Riding Hood. To preserve the surprise aspect, Avery already has the wolf dressed in his grandma garb and positioned in bed—the audience already knows how the story goes, and there’s no use spoon feeding it to them. Such an itch was already scratched with Little Red Walking Hood.

Instead, Blanc engages in a signature shtick synonymous with multiple villains—gravel voice, catch mistake, clear throat, revise self through sickly falsetto.

“Come in, Little Red Riding Hood!” Eyelashes summoned out of thin air that weren’t present with his normal intonation effectively complete the transformation.

Enter Little Red Riding Hood, sans red, sans riding, and sans hood.

Rod Scribner’s handiwork is exceedingly noticeable upon his variation of the signature Avery head turn take—more wrinkles, more looseness, and more distortions in features such as the mouth and eyes that feel organic rather than simple geometric shapes. Instead of accompanying the wolf’s bewildered spasms with a signature blaring music sting of shock, Avery and Stalling coyly employ a brazen sting of “A Tisket, A Tasket” that affirms the indisputable presence of Goldilocks. Not only that, the melody—often employed by Stalling and company to assert a tone of immature, childish ridicule—seeks to mock the wolf for his plan foiling.

Goldilocks shows no fear nor hesitation towards the wolf, seeing as that is not the goal of the scene nor cartoon. Instead, the heavily accented nasal Brooklynese (that, during certain deliveries sounds practically identical to an early Bugs Bunny) from the wolf digs into his visitor: “‘Eyy, what is dis, a frame-up? Who are you?”

Avery’s occasional overzealousness with camera movements can get slightly distracting through their arbitrary inclusion, but the quick cut in old Goldilocks as she introduces herself through grating, breathless squeaks and giggles works effectively. It places her in indisputable focus, purposefully obtrusive in its employment as though to assert her innocent yet decidedly obnoxious appearance. It isn’t a matter of adjusting for clarity. Rather, she’s interrupted the wolf’s story—now she’s going to interrupt the filmmaking by putting all eyes on her.

“Why…” Hansell’s subtle giggle that follows is gloriously disingenuous in its intent, yet antithetically conveys oblivious, cloying earnest on Goldie’s part. “I-I’m little Goldilocks!” Avery pulls out all the stops for the voice direction on Hansell’s next delivery, purposefully trying to grate the audience’s nerves through her honest whining. “Isn’t this where the Three Bears liiiive?”

The wolf’s mocking sneers of “Nahhh, dis isn’t where da T’ree Bears liiiive!” are meant to be somewhat indicative of the audience’s own response to Hansell’s voice. Hansell herself isn’t annoying—she’s a gift, and perfectly cast, excelling tenfold at what she does. Rather, Avery’s voice direction is, and that’s entirely the point.

“Dat outfit lives two miles down da road at da foist stop signal,” again cements that Ben Hardaway couldn’t have possibly written the cartoon—too clever and natural for his tastes. Likewise, Scribner is succinctly cast in his animation, excelling in his portrayal of the wolf’s brusqueness. All of the wrinkles and distortions make him seem more haggard, scraggly, mean spirited, antagonistic.

Especially when Paul Smith takes over the next scene of the wolf shooing Goldie out the door; both characters look much more simplistic and smooth in their appearance. Not to a detriment, their designs certainly serviceable, but not nearly as rife with character as what is present in Scribner or McKimson’s animation.

Nevertheless, Goldie’s prima-donna attitude is exceedingly clear in both animation and delivery as she scoffs “Hmmph! What’s Red Riding Hood got that I haven’t got?”

Perhaps the gag in the cartoon’s opening noting her subcontracting holds more weight to it than initially thought.

Even then, she has a point—one that the wolf himself comes to realize. Why should he wait for Red when an equally tasty morsel just sashayed out of his hands?

From the gradual, bloated pause of realization to the fervency in which wolfie whips the door back open, Avery’s discrepancy in speed encourages a naturalistic balance, the wolf’s movements organic rather than evenly timed pieces of phones in acting. His “Saaay! Why didn’t I t’ink of dat? Yeah!” is one delivery in particular where his Bugs Bunnyesque shines strong.

Avery makes a point to assert the wolf is no dope—not only through his realization, but his conveniently vast collection of fairytales. Nice, varied posing from the wide shot, and cohesive solidity on the close-up of his uncannily human hands grabbing his Goldilocks book. A vignette surrounding the plot propelling paragraph allows ease of read for the audience and perhaps even the wolf…

“Yeah! ‘dat’s it!”

So, in indisputable Avery fashion, the wolf hails a taxi. Perhaps the only thing as Averyesque as completely and joyously destroying the narrative of a classic fairytale.

Likewise with the classic Avery 1-2-1 pacing of the next gag; wolf tells the cabbie to “step on it” towards the abode of the Three Bears, hops in the cab, and jumps out once more to whisper a sly addendum of “I’ll take care a’ any tickets.”

Animation of the taxi itself is a bit clunky through perspective, but quick enough and concealed by a fade to avert any suspicions.

And, rather than delegate a belabored sequence of the wolf struggling to get into the Bear family’s cottage, Avery and the wolf both cut the fat by having him sneak in straight through a window. Timing his furtive footsteps to “Mysterious Mose” seeks to tie a largely anarchic character back to the narrative. Indeed, the narrator has been absent, the stilted rhythm touted by the remainder of the cartoon paused—the wolf operates completely on his own terms. As such, the reminder of his own “theme song” indicates a growing return to reality, as well as crossing of territories. It’s as though entering the home of the Three Bears enabled the wolf to enter their narrative and their rules, too, if only for that brief scene. Friz Freleng would specialize the tiptoe walk the wolf does before diving in Baby’s bed with many a cartoon of his own.

Sure enough, Bruce’s narration resumes as a visit to the Bear family is shorn yet again. He doesn’t engage in the “The Papa Bear… the Mama Bear… and the Baby Bear” format, as that in this instance may become a bit too grating, especially after a brief interlude from such patterns. As such, we follow Papa’s adventures as he imitates a siren, clearly smitten with his folly talents.

“Sounds kinda like a police car, don’t it?” The seemingly arbitrary close-up again seeks to provide a snarky, self aware spotlight to the simplicity of Papa rather than serve as a moment of clarity. Especially considering that the camera trucks right back out to accommodate the barrage of belly laughs that follow.

That, and to take Mama’s spousal violence into account. Much like the wolf’s head spinning take, Papa’s own bewildered head spins are quick and energetic rather than obligatory. Thus, the camera pans to give Mama her rightful glowering spotlight. Again, certainly not the first nor last instance of the battle axe wife stereotype to be harbored in an Avery cartoon. If anything, it does help in fracturing the fairytale further and conveying the intended dysfunction of the family. It has been set in stone that this is no ordinary retelling of a classic.

“Now, up to the Three Bears’ house…” Another obligatory sting of “Home Sweet Home” to bring the story back to momentary harmony.

“…skipped little Goldilocks.” Same cloying walk cycle, same cloying theme of “A Tisket, A Tasket”.

Further grounding to the story is exercised as Goldie used the littlest bear’s door to get inside; combining Averyesque conventions with the source material to be true to both.

“But waiting upstairs…”

The angry music sting of “Mysterious Mose” timed to the wolf’s impatient finger taps speak louder than any Brooklyn accented quips could.

A fade to black as attention is diverted elsewhere. Same introduction of the beautiful green chorus, same fitting accompaniment of Mendelssohn’s “Spring Song”…

“…came Little… Red Riding Hood!”

Bruce sounds just as surprised as the audience presumably is. Indeed, the seemingly forceful obedience to the film’s rhythm is all a deliberate preparation for an impending antithesis. Even Red’s theme, the ever fitting “The Lady in Red” is sleek, modern, a newer song to indicate the breath of fresh air intrinsically tied to her appearance.

Sara Berner provides Red’s vocals as well. Shrill, pinched by an accent not unlike the wolf’s, her performance somewhat foreshadows Bea Benaderet’s memorably and skillfully obnoxious performance as Red in Little Red Riding Rabbit. Instead of stumbling upon a wolf in grandma’s clothing, she instead finds a note conveniently left on the bed (that is, worth noting, much closer to the fireplace than in previous shots—we won’t be in here long, and a shorter distance traveled inside the home means the quicker more action can be harvested.)

Avery incorporates both the new and the old with a close-up of Red surveying the note. New applying to the appropriation of Liberty magazine’s somewhat condescending yet nevertheless informing reading time estimates, old applying to a deliberate reuse in format—and verbiage with “Got tired of waiting”—from Cinderella Meets Fella. Instead of a somewhat homely yet mournful background score found in the former, Avery goes for the gut with a dirge of “Funeral March” to indicate Goldie’s impending fate. “Love” rather than “From” The Wolf is a more subtle yet equally humorous detail.

Instead of panicking, Red gets down to the case thanks to modern conveniences once again. In this instance, a telephone absent to prying audience eyes previously.

We then dissolve directly to Goldie preparing to take her nap, any mention of porridge indicated purely through Bruce’s narration. No spoon feeding necessary. Goldie’s design is somewhat off for certain frames, but the downward perspective is engaging, varied, and clear, an added incentive.

Her trek up the stairs is interrupted by the sound of the phone ringing. A mere camera pan, upward layout continuous as the staircase is joined to the kitchen, is all that blocks Goldie from accessing the phone. She answers it promptly.

Thus, a meeting of the minds. Avery loved his split screen gags, as evidenced in cartoons such as Thugs with Dirty Mugs. To him, the divide between the screen isn’t a metaphorical barrier, but a mere separator waiting to be breached. Red asserts this after she and Goldie make introductions, forking over the note she found from “that skunk, the wolf” with no issue.

Goldie is appreciative, shaking her hand for the favor. Already, the conversation indicates that the two know each other—fairytale heroines must stick together. Such notions are confirmed by Goldie’s squeaky voiced dismissal of “See ya later!”

Even if “later” means about two seconds from then. In another footnote of indisputable Avery conception, Goldie returns to fish out any remaining coins in the coin slot…

…only to be busted by the audience. Bruce doesn’t clear his throat or weasel his way back in, no indication of the audience’s presence forces its way into Goldie’s territory. Her realization is all natural, and likewise with her guilt. A gag that is sardonic in conception but innocent and naïve in delivery; the wide-eyed ogle as she briefly slaps her hand to her mouth evokes more sympathy than it does scorn. Perhaps this mister LeBoy alluded to in the credits doesn’t pay as well as one may figure.

Returning to the star ursine family, the Bears take Bruce’s suggestion of “hurrying home to their porridge” to heart. A shot of the cottage’s interior reveals them literally dashing into their rightful positions.

Avery’s balance of demeanor is masterful between the vast cast of characters; the Bears are the stars of the story, and most intrinsically tied to the narrative. Thus, much of their movements and actions feel purposefully spoonfed, dronelike, obligatory; they abide to the short’s rhythmically stilted structure the most, their actions and phrases almost always initiated by the narration. While there are purposeful lapses (Papa’s never ending gut-busting fascination with, well, everything, Mama’s hints of being an overbearing battle axe) to assert the true tone of the cartoon, they are much more puppet like than Goldie, Red, and certainly the wolf.

As such, their reactions to the empty porridge are spurred on by appropriate music snatches and camera pans rather than spontaneous thinking.

Likewise, the whole “somebody ate my porridge” shtick is mostly spared. Avery asserts the drone-like obedience of the Bear family by having only the Baby whine “And they ate mine all up!” No indication of who that they is, no need for beginning a sentence with a conjunction if nobody has spoken prior. Instead, the line feels purposefully stilted and purposefully to the point.

Anarchy and spontaneity is founded once more from the wolf. That is, his plans of hiding out and awaiting Goldilocks are foiled by a comically grandiose—if not violent—sneeze; no explanation as to why he sneezed, as no explanation is needed. It is intended purely to usher the story along, its wryness supported through the unnecessary screaming from Blanc as he heaves a wonderfully arbitrary “AH-CHOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOO!!”

No mistaking that sound. “Robbers!”

In a clever and almost seamless shot (bumps appearing only due to the floor missing for a few frames, waiting for the pan to catch up with the camera), the table is animated in perspective to match the Bear family huddled under the table. Much more quick and streamlined to do a pan than cut to a boring old close-up shot. Again, such sophistication in staging decisions disprove Hardaway’s story credit further.

Taking one for the team, Papa tells the others to stay where they are while he heads to scope things out.

So, with that act of bold selflessness in mind, Avery seeks to immediately disprove it by dissolving to Papa engaging in another fit of hysterics as he lumbers up the stairs. His easy pace and jovial, simple disposition certainly disprove the tension of the prior scene.

Sensing the audience’s confusion at the disconnect, he grows confidential. “I know there ain’t no robber up there. Just a tiny little girl named Goldilocks.” Wonderful solidity in his movements and great personality in his acting, the toothy grins reeking of mischievous disingenuousness.

His addendum of “I read this story last week in Reader’s Digest” isn’t entirely hilarious for its meta humor, so much as the suggestion that Reader’s Digest would ever house such a kiddie fairytale to begin with. Avery’s sincerity in his vocal deliveries are not to be understated—he brings a jovial warmth to the character that almost pokes fun at viewers who would describe his deliveries as “jovially warm” to begin with. Everything truly is one big in-joke.

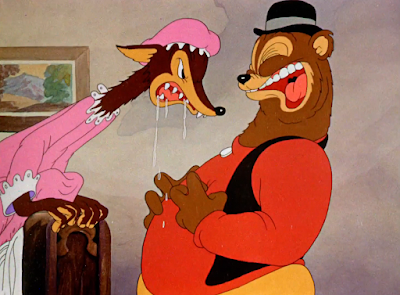

Rod Scribner soon after animates a gorgeous sequence of Papa approaching the wolf, reduced to a mere mound of linen. From intricate hand movements to more naturalistic timing, solid head tilts to distortions more appealing and engaging rather than grotesque, his draftsmanship is rife and put to much better use than he was ever given in Hardaway’s unit. Likewise, having amusing dialogue to animate to (“You come outta that bed, you cute little curly headed rascal!”) provides additional incentive.

He is best in his wheelhouse when Papa realizes he is addressing a decidedly un-cute, un-curly headed rascal. Gummy teeth, giant eyes, plentiful wrinkles, and organic distortions through frantic mouth movements that render Papa a giant lump of rubber rather than a bear all cement Scribner’s animated identity, perhaps one of the easiest animators to identify thanks to the above attributes. He would learn to master such plasticity and fervency as his tenure expanded, particularly under the direction of Bob Clampett, but his drawings here are certainly no less impressive by any means. As mentioned before, his comparative unconventionality births a whole lot of life and character into his subjects that is not at all taken for granted by the viewer.

Struggling to get any words to come out, Papa ends his hyperventilations by rushing away from his predator. Thus initiates another fantastic sequence whose flow is cohesive and impressive—unfolding all in one fast camera pan, Papa bolts down the stairs (camera tilting to disorient the audience and sell his speed), dives under the table, promote furniture to fly, grabs his entire family in the process, and runs through the closed door rather than out. In all, the act doesn’t even take five seconds to unfold. An incredible exercise of control that is uninhibited through over involvement or needless meticulousness. Controlled, but not suffocated. Controlled in that every little action has a thought process behind it that led to the seamless result projected on the screen.

“So over the hill went through Three Bears.”

“The Papa Bear…”

“The Mama Bear…”

The Bear’s Tale admittedly does come to a bit of an abrupt end, but it’s one that’s fitting. Fitting in that drawing the story out any longer would kill the momentum, fitting in that it deceives the audience into thinking they’d get a tale of happily ever after, and fitting that it ends on an ass joke.

“And the little bare behind.”

For a menagerie of reasons, The Bear’s Tale is certainly one of Avery’s best at the studio. (It’s certainly one of my favorite cartoons of his during his tenure at Warner.) Some of it may indeed boil down to the mere relief in format—something other than a travelogue, huzzah!—and that Avery’s two previous fairytale outings, Little Red Walking Hood and Cinderella Meets Fella, are other standout cartoons. Acquisition of animators such as McKimson and Scribner play a big role as well, enabling a broader range of more sophisticated character acting, design, emotion, etc. Being well directed, which is an understatement, is however most responsible.

A deceptively simple premise ripe with opportunity for all kinds of self indulgent subversions and commentaries reaps great benefits. As repeatedly mentioned in the review, it’s exceedingly likely that you won’t come in contact with someone who doesn’t know the beloved tale of Goldilocks and the Three Bears. Universal knowledge of the story immediately eliminates the need to spoon feed the audience. As such, jokes can be sought faster and appear in greater concentration, shots can flow smoother thanks to eradicating needless exposition, and well established characters can be twisted and manipulated into however they please with no repercussion—especially if their characterization offers little to begin with.

Indeed, something as simple as a camera pan or even a flow of shots reads as a joke in itself. Repeated establishment of “The Papa Bear… the Mama Bear… and the Baby Bear”? Utilized as a joke. Repeated musical motifs? Utilized as a joke. Purposefully deceptive idyllic imagery? Utilized as a joke. Every little aspect of this cartoon has a great deal of thought behind it, and that applies even to self indulgences the audience has been privy to before—such as the wolf hailing the taxi or Red and Goldie splitting the screen. Very rarely, if at all, does any one aspect of the cartoon feel phoned in. Not unless it has comedic potential.

Perhaps the biggest criticism of the short arrives with a lack of a solid ending or wrap-around story—certain aspects such as the whereabouts of Red or Goldie in particular are left hanging, and the wolf seems to beg a bigger reaction than allowing Papa to gawk and hyperventilate at him before slipping out of his fingers. Regardless, the rest of the cartoon is so enjoyable and so focused, so controlled that it doesn’t come as too overwhelming of a detriment. Avery has made it exceedingly clear many times throughout the picture that this isn’t a cartoon about story, it’s a cartoon about disestablishing story. As such, a seemingly incomplete ending doesn’t come as a surprise, even if it does feel the slightest bit disappointing. More a case of every other aspect in the film being so strong.

Nevertheless, The Bear’s Tale is a wonderful display of how effective and personal Avery’s filmmaking is even 82 and a half years later. His adoption of a more wry, mischievous control rather than embrace of hyperactive antics that tire the audience out has paved the way for some innovative, truly game-changing thinking. Every little gag, every little action, every little beat is and feels purposeful. Even with that in mind, the cartoon never once feels condescending or suffocating—despite being so controlled and finely tuned, it remains loose, free flowing, and lighthearted; a very effective combination that is often hard to master. It is not hard to master if you are Tex Avery, and he would continue to assert that with coming cartoons.

.gif)

.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment