Release Date: March 16th, 1940

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Tex Avery

Story: Rich Hogan

Animation: Paul Smith

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Lou Marcelle (Narrator), Mel Blanc (Bear, Scoutmaster, Gas Attendant, Polar Bear, Dogs, Bobcat, Gila Monster, Tourist), Sara Berner (Deer, Girl, Echo)

(You may view the short here!)

While a plethora of travelogues are sure to succeed this one, perhaps none as are cohesive, daring, to the point, subversive, and just plain funny as Cross Country Detours. One of—if not the—longest shorts yet at a runtime of about 9 and a half minutes, Tex Avery makes ample use of his time by stuffing it full of lighthearted, sharply executed, and at times flabbergasting sight gags and jokes that would seldom be replicated in their sheer effectiveness here.

On a more technical note, this short notes the final animation credit of Paul Smith. Having been a mainstay at the studio since the very beginning during the Bosko days, he would move on to the Walter Lantz studio and stay there for much of the remainder of his career, animating and later directing an abundance of Woody Woodpecker cartoons.

Likewise, voice over artist Lou Marcelle is cast as the narrator rather than Robert C. Bruce. Marcelle fits the niche quite nicely, maintaining the same warm patronization in his voice that makes Bruce such a hit. Marcelle was native to Warner Bros, providing voice overs for their movie trailers—perhaps most notable is his narrating the trailer for Casablanca.

Time is seldom spared as the audience gets to hear his vocal tones in action. Here, our travelogue places a focus on a “nature tour”, promising “interesting animal life and scenic wonders of our country”. Thanks to the recent restoration of the cartoon, the original titles have been salvaged and thus the narrator’s monologue preserved; his orations begin over the title card, which have been excised in the Blue Ribbon reissue, thus losing some of his dialogue in the process.

Avery’s acquisition of Johnny Johnsen as a background painter has truly elevated the quality and interest of these films. Genuinely breathtaking background paintings mold well with the bombastic narration, striking the intended effect much more successfully than had such grandiose writing and audio been spliced overtop the vague, melting brush strokes of Art Loomer. Johnsen’s work adds a cohesiveness and authenticity, truly bringing the format of the film closer to the source of which it is lampooning.

Here, the narrator introduces us to the visual splendor of Yosemite—“known to many a traveler.” Such spectacular visuals provide a segue into the first gag, one comparably yet purposefully less sophisticated in design.

A gag stemming from A Day at the Zoo and soon to be repeated again in Circus Today, a bulbous, dopey tourist obliges by the narrator’s comments on the temptation to feed the wildlife. Signs mean nothing to him; furtive glances left and right—armed with an equally trepidatious music score—attempt to raise the severity of the tourists impending misdoings, indicating guilt and an acknowledgement of consequence.

That is, if anyone happened to be nearby. Such is not the case, allowing the tourist to gleefully fork over a sandwich to a visibly flummoxed bear.

Correction: visibly furious. The outrage of the monkey seen in Zoo has been further exaggerated in this case. While the most notable increase of aggression is the addition of “LISTEN, STUPID!” to the standard “CANT’CHA READ!?”, the bear also smacks the tourist himself right on the head rather than merely smacking the food out of the way. Both add a humorous, extravagant ferocity to an already amusing gag—Blanc’s screeching vocals are always a hit.

Schlesinger and company most have thought the same—a comic strip was made depicting the same scene. This certainly isn’t unheard of; Porky the Fireman got the same treatment, and a Bugs Bunny comic strip would be syndicated starting in 1942 and running all the way up to 1993. Schlesinger’s signature was present during his tenure at the studio, as is the case with the Cross Country Detours comic here, despite not drawing the strips himself. Much like how Walt Disney did the same thing.

“We also find other animals in the park. Here’s a shy little deer! Hello, deer.”

Another loose reprisal of a similar gag, Avery springboards from the gazelle’s striptease in The Isle of Pingo Pongo to allow the deer here to channel the likes of Mae West, standing big and talk with her sultry “H’lo, big boy.”

Since Pingo Pongo, Avery and his crew have become much more elaborate with their art direction—less loose, less rubbery, more solid and cohesive in construction. As such, the deer here is more woman than animal, aiding the shock value of the gag and transformation as a whole. Rotoscoped footage of her sauntering away with the utmost casualty reaps great benefits—natural to an uncanny degree. Transforming her chest markings into that of a swimsuit additionally makes great use of her design.

“Boy Scouts make Yosemite their annual camping headquarters.” Indeed, an awfully nervous scoutmaster dashes into the foreground, cautiously alerting an elderly gas attendant. Marcelle’s noting of the matter in his narration indicates we are meant to give the scenario our full attention.

“Pardon me… may we use your washroom?”

A succinct example of show, don’t tell, the nervous scoutmaster merely displays his messy hands to the attendant. Never says how he got so messy in the first place, never elaborates on who this “we” is outside of the context clues given from his uniform. Instead of being bogged down by meandering, needless dialogue, Avery wastes no time in the setup; clarity is maintained regardless, and the setup is not the priority. The punchline is.

After given the go-ahead from the amiable attendant, the scoutmaster whistles to his boys off-screen…

…thus arriving to the punchline: an endless stream of Boy Scouts waiting dutifully to flood the tiny washroom. As to be expected, a number of components render the payoff so satisfying. Sheer quantity of the boys alone is certainly the most notable, as is the fact that they’re already standing in line without any indication of their presence prior. Having them running into their positions and coming to a halt would slow the momentum and lessen the sharpness intended by the gag. Moreover, that the boys all have varying designs makes them seem even more vast than they already are; the assortment of children feels more natural, believable, and slightly slows the viewer’s eye in trying to dissect what is on the screen. There is a natural disconnect as the audience digests the differing designs that wouldn’t be present if the designs were all the same, subconsciously making the herd feel smaller since it doesn’t take as long to process the little details. All apply to the brief, somewhat stilted shot of the boys exchanging hopeful glances in differing directions.

Stampeding running sounds truly top off the gag nicely, as does the trumpet fanfare in the background, seeming to beckon a herd of horses rather than small children. How they all fit into the outhouse is never expounded upon or even meant to be pondered. Absurdity is meant to be embraced rather than questioned.

A self indulgent topper, the pint-sized straggler is a favorite of both Avery and his cohorts alike; a gag that stems as far back as the Harman-Ising days.

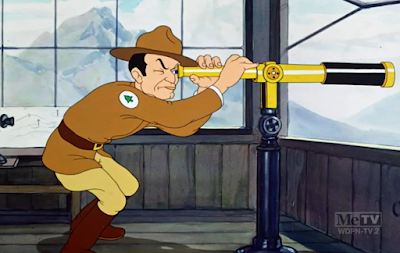

“Stationed high on their lookout towers, firefighting rangers are continually searching for carelessness which may result in the destruction of these beautiful forests.” Worth reiterating is Johnsen’s artistic prowess with the background paintings—“beautiful forests” carries actually weight and meaning thanks to his talent.

Like the Mae West deer, the construction and design of the ranger shows great artistic growth—if not a bit of stiffness—in Avery’s design sense. So much so, in fact, that he seems over-designed, as though meant to convey a caricature of some sort. Of who, not sure. Oddly specific as his design may be, it doesn’t come as a detriment—it instead increases an ironic sense of heroism, dramatics, austerity, clueing the audience in that this uncanny-in-his-attractiveness ranger will serve as the hero for whichever coming catastrophe is soon to blossom on-screen.

Said catastrophe unfurls entirely in pantomime. Though not a word is said, every action is clear in its intent. Sharing the point of view of the ranger, the telescope from which he peers out of settled on a photographer heartily chuffing away on a cigar (but not after another gorgeous showcase of backgrounds, foreground overlays furthering an added depth and believability to the surroundings.)

After sucking the stogie of all of its carcinogenic properties—lip smacking facetiously included to indicate the photographer’s loss of interest—he tosses it down on the forest floor and continues along his way. Even the inclusion of a cigar alone is an amusing choice; cigars are much bigger, more imposing, and more pompous than a measly old cigarette. Further attention is called to its fire risk as a result, but also indicates a subconscious smarminess of the photographer which is maintained through his careless, lip smacking mannerisms.

While the still smoldering stream of smoke on the cigar freezes in a cel error, the intent of its danger is still nevertheless conveyed. Especially through the incongruous, rubbery, eye-widening take of the ranger, his model practically assuming the identity of an entirely different person as he rushes out of the watchtower.

Stolid profiles are nevertheless reinstated as he dashes over hill and dale to the sight of the potential fire. From the sheer speed, perspective, and distance alone, the gag succinctly foreshadows a very synonymous chase sequence in Avery’s Dumb-Hounded at MGM. That the two sequences are even comparable at all indicates further artistic growth on Avery’s side; slowly but surely, the identity that he would fully cement once moving over to MGM is coming to fruition. The sequence here is already fantastic through its speed and caricature—frantic siren effects add a palpable mischief that truly ties the scene together neatly—and to think that it would still be expanded and reworked to be faster and more absurd is astounding.

Priorities are nevertheless delegated to a coming punchline once the ranger skids to the cigar in question and grabs it. He spares a few head turns to see if the perpetrator is nearby…

…or so we are led to believe. After a delightfully grotesque, toothy grin, the ranger instead pilfers the remains of the stogie for himself. All of that fuss just to sustain his nicotine addiction. His proud posture as he struts along rubs further salt in the wound in the most delightful way possible.

Almost three minutes into the cartoon’s runtime, we only now move forth from our first destination. The lengthy runtime of the cartoon proves to be a benefit, as Avery is uninhibited by the need to compress jokes into one single setting and flee to the next. While lingering on any one scenario for too long can grow boring, such is hardly the case here. The jokes and setups harbored in Yosemite are all distinguishable from each other to maintain interest and novelty, but are nevertheless united through their shared setting and encourage a cohesiveness seldom touted in Avery’s travelogues. The effect does not go unnoticed.

Now, Marcelle guides us through Utah—more specifically, Bryce Canyon. Through the courtesy of a faux multi-plane pan, Johnsen’s backgrounds continue to impress the viewer and support the flowing orations of the canyon’s natural splendor.

Marcelle notes the “strange and grotesque formations”—while indubitably leading to a grander climax, a carved formation of what appears to be the subject of James Abbott McNeill Whistler’s famed The Whistler’s Mother. A very subtle detail that doesn’t intend to command a great wealth of attention, but nevertheless enriches the overall establishment of the setting.

Descriptors of “strange and grotesque” apply moreso to “this natural bridge”—a full set of teeth carved into the rocks. The salmon coloring of the stone renders it practically indistinguishable from gum tissue, as though the formation is of actual human flesh—likewise, the gold tooth adds its own sardonic commentary that enables the playful absurdity to sink in just a bit more effectively than the alternative of no gold tooth at all. Glittering visual effects reflected off the tooth ensure its inclusion is not missed by the audience.

Unlike his devotion to Yosemite, Avery finds no need to exhaust Bryce Canyon of all gag possibilities and instead transitions to the next location. Such brusqueness provides a solid buffer against the lengthier dedication to the Yosemite setting, encouraging variety in the cartoon’s structure and maintaining audience interest.

Double could apply for selecting Alaska as the next highlight. A complete antithesis in climate to the canyons of Utah, even the mere difference in color scheme—icy hues of blues and whites reigning supreme over the warm pinks and oranges of the canyons—again endure the landmarks are distinctive, recognizable, and seldom blend together to keep the audience engaged.

Following a lengthy pan of the Alaskan snowscape, the camera focuses on a “perfectly contented” polar bear scrambling onto a lone block of ice floating in the water. Here, Marcelle indulges the viewer on a brief biology lesson on the biological makeup of a polar bear and how they stay, in his words, good and warm.

His comments practically beg a rebuttal. Though the camera close-up on the polar bear’s face is a bit overkill, it wryly supports Blanc’s steely, apathetic, very natural dismissal of “I don’t care what you say, I’m cold.”

We are therefore shunned in the process. Demonstrating his ass freezing through a painted overlay is again somewhat unnecessary, the sequence securely tied through the bear’s comments alone, but it certainly doesn’t come as a detriment. Instead, it seeks to further disprove the narrator’s confident, self-assured comments and shake his credibility.

Marcelle’s credibility is further shaken once his claim of dogs being “perfectly happy here” are disproven. One lone husky shows great interest in a conveniently placed sign directory all pointing to various Californian landmarks…

…and is more than happy to follow those directions. Following an appropriate score of “California, Here I Come” and some weaving perspective shots of the dog running along the fated path, the narrator’s dismissive “Oh well. Good luck!” indicates this pooch will be the highlight of choice bridging various sequences together. A fade to black bestows momentary finality on such misadventures, providing a solid transition to the next piece of business.

Still attempting to maintain the audience’s attention, another drastic change in setting is in order. As such, per the narrator’s direction we head southward to follow a slinking, conniving bobcat. Again, Avery’s growing handle on realism and construction yields great results in maintaining the intended drama in tone—compare his design to the somewhat synonymous but much more loose wildcat from A Day at the Zoo not even a year before. While the wildcat’s design reaps its own benefits, Avery’s approach here fits the tone attempting to be met. Comments of “this tense drama of animal life” don’t hold much water if the designs of the animals in question don’t look or feel as though they pose a significant threat. That is luckily not the case here.

Elongated runtime of the cartoon enables Avery to milk said drama for all its worth, yet never feel excessive. Much of that can be owed to Marcelle’s narration in this particular sequence. Upon introducing the prey, “this poor, helpless little weakling…”, Marcelle drastically shifts his intonation and syntax depending on the camera’s focus.

It is how we end up with back and forth panning between the bobcat and baby quail—narration turns from emboldened and tense to piddling and disgustingly saccharine. Stalling shifting between the appropriate adjoining music scores (threatening when met with the predator, sardonically pathetic for the quail) furthers the juxtaposition, and the mere act of the camera panning back and forth becomes a joke in itself. Clear, unmistakably delivery that succeeds greatly at evoking pathos from the viewer, but also nudging them in the ribs for falling for the narrator’s sappy shlock.

For anyone accustomed to Avery’s filmography—or Warner Bros’ filmography as a whole—the punchline of the bobcat collapsing to the ground and sobbing in a fit of Blancian hysterics does not come as a surprise, but the novelty is by no means lost; especially when remembering that this instance here is quite likely one of the very first variations on such a gag to begin with. The ferocity of Blanc’s screams (“I CAN’T DO IT! I CAN’T! I CAN’T GO THROUGH WITH IT! I CAN’T, I CAN’T!”) is enough to sell it alone, but all of the painstaking buildup render the punchline even more cathartic as a result. Again, the longer runtime of the cartoon aids in allowing Avery to create elaborate setups for his jokes that don’t feel as rushed or vague as they often have a tendency to. From viewing this scene alone, it’s no wonder why it would be repeated so often.

Likewise, the coming sequence may very well be one of the sharpest scenes Avery has ever directed during his tenure at Warner Bros. Almost blind sighting in how stupidly simple yet irreverent it is, Avery pushes the bounds here perhaps the farthest he has dared to yet in his near 5 years of directing—as a director who has made a name and built an identity on boundary pushing, that says quite a lot.

Deceivingly tranquil shots of a marsh slowly lure the audience into a false sense of peace and security. From the lush backgrounds to the gentle music, from the soft songs of the frogs to the narrator’s gentle insight, the audience prepares willingly to be condescended to with whatever enthralling factoid awaits.

“Here, we show you a closeup of a frog croaking.”

A dutiful servant to the tones of the narrator, the frog wastes zero time in whipping out a pistol and shooting himself right in front of the audience. That his dead carcass catapults back into the water ensures we will be met with no witty retorts from the frog or any sort of indication that he’s okay. A funeral dirge in the background and somewhat lingering shot of the now empty lily pad assert that he’s a goner.

Whereas follow-ups and toppers sometimes have a tendency to feel unconfident, an over correction in hoping that the audience is pleased by the gag rather than having enough faith in both the joke and viewers. A slide touting the lugubrious declaration of “PATRONS NOTICE — We are not responsible in any way for the puns used in this cartoon. ~ The Management” is a rare case in which the follow-up is just as funny and satisfying as the main punchline.

Suicide gags would soon become common place, and this certainly isn’t the first one to be featured. Yet, through its sheer promptness, boldness, and unceremonious delivery, the gag still rises a genuine shock out of viewers today that is just as fresh and blind sighting as it was 82 years ago. The inclusion of the disclaimer card would be especially formative for Avery, a device he would slip often into his forthcoming MGM cartoons. A great success here that is genuinely unparalleled, even from Avery himself.

Understanding this himself, a more leisurely, curt break is delegated to the husky from Alaska interrupting the narrator’s introduction of the New Mexico desert. Winding perspective and speed changes in the camera movements seek to maintain visual interest and naturalistic momentum which pays off quite well. The audience knows a greater punchline awaits at the end of the cartoon—no use dwelling on it now. Enough to be coherent, but not enough to bring the film’s rhythm to a screeching halt.

On the topic of coherency, Avery maintains the same setting and atmosphere; the New Mexico setting wasn’t just a brief intermission to accompany the dog. Instead, it harbors one of the cartoon’s many highlights, if not the biggest one at all. We find a lizard skittering around the desert, movements realistic through its irregularity and erratic timing.

“Here is a lizard—which, as you all probably know, sheds its skin once a year. Let’s watch this interesting procedure.”

A more glamorous cousin to the sultry doe at the film’s start, about a minute of the cartoon’s runtime is delegated to the lizard performing an elaborate strip tease with the same utter nonchalance as the former.

In fact, the studio hired a professional model just to shoot the rotoscoping reference footage. Marcia Eloise (who adopted stage names such as Teala Loring and Judith Gibson) was revealed to be cast as a model according to an entry in the Los Angeles Times, dated August 27th, 1939. Some of the reference footage can be found at the 3:30 mark here.

Indeed, her casting reaped great benefits. While Tex Avery later confessed he wasn’t even sure whether lizards shed their skin or not (making Marcelle’s comment of “as you all know” even more amusing), he did note that the sequence got big laughs—and for great reason. The lizard’s animation is sophisticated, elaborate, graceful, tantalizing enough to hypnotize the audience for a full minute straight without losing its novelty once, but playful enough to remind the audience not to take it too seriously.

Worth noting is Bob Clampett’s take on the same gag later on. More specifically, Art Babbitt’s animation of Daffy performing a strip tease synonymous to this one in The Wise Quacking Duck, succeeding the cartoon by three years. While Babbitt later denied using any reference footage for the scene in question (birthing this timeless quote of “I mean, where the hell am I going to get live action for a duck doing a strip tease?”), reviewing the two scenes side by side reveals striking similarities.

That both scenes use the same song choice of “It Had to be You” in the same music key is uncanny enough in itself, but there are certain poses and gestures from Daffy that certainly align with the footage of the lizard here. While both scenes are independent of each other in their nuances, the example in Wise Quacking not at all a carbon copy of the example in Detours, it doesn’t seem a stretch to say that Babbitt likely used Eloise’s footage as reference and later misremembered or dismissed the idea. Of course, this is all speculation and nothing more, but the point still stands that there are enough similarities between the two sequences to draw comparisons. One of those comparisons being that both are incredibly funny and sharply executed.

Detours has an advantage that Wise Quacking does not—a solid topper. More specifically, another irreverent punchline that continues to push the boundaries and tease the censors in quite a literal sense. As the lizard works on unsheathing herself of her final layer of skin, pasty green coloring suggesting nudity, a joyously obstructive CENSORED bar interrupts any further sensual suggestions. Between the abruptness in which the censor appears—just popping right onto screen instead of suffering a slight delay through sliding into place—and the knowing side-eye at the audience, self awareness on all fronts pay off greatly and come as a satisfying reward to a satisfying sequence. Yet another gag that maintains the same timeless shock value and novelty that it did at the time of its conception.

Momentum continues confidently in the next spotlight. A fan of split screen gags, Avery expands upon what Believe it or Else established through its immersive self awareness. Rather than embarking in a series of magic tricks and scolding the audience for peeking, like the former, the audience awareness here is almost out of protection; the fade to black from the previous scene never comes back up. Instead, Marcelle narrates gravely over the black color card, accompanied only by a droning drumroll:

“Ladies and gentlemen, your attention please. The next scene is quite gruesome. So, for the benefit of the children in the audience, we will split the screen.” Indeed, a white line cautiously crawls its way down the middle.

“The left side for grown ups…”

“The right, for the children.” To cement the juxtaposition, Stalling slips a purposefully chiding, saccharine, childish music sting.

“For the grown ups, a hideous Gila monster.” Exaggerated syntax, using phrases such as “hideous” attempt to facetiously raise the stakes of the horrors soon to be witnessed by the audience. A fade on the screen’s left side lifts, revealing the fiend in question.

Like the bobcat scene, Marcelle utilizes his intonation to sell the antithesis as sardonically as possible. His “For the children… a recitation,” is comedically milquetoast, reserved, truly embracing his typecasting as the ever well meaning but condescending narrator. True patronization at its finest.

Thus spawns Sara Berner providing the delightfully grating vocals of a toddler reciting Mary Had a Little Lamb, accompanied liberally by the snarls and growls of Mel Blanc as the gila monster. Stalling’s tinkly accompaniment of “Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star” is the most noticeable, but he does slip in a subtle, more furtive backing to gel with the Gila monster as well. While all of this unfolding at once sounds like a recipe for disaster and chaos, Avery masterfully times it just right so that the scene is almost rhythmic—the Gila monster’s growls and snarls are loudest between the girl’s verses, but still provides enough ambient noise during her dialogue to feel naturalistic and obtrusive.

Historian and animator Mark Kausler identifies the animation as Rod Scribner’s handiwork, which is justified through the mouth shapes on both the reptile and the girl, tapered fingers on the girl as she curtsies, and the wrinkles in her dress as she does so. In all, the scene is a master class of what makes Avery so great—diligently controlled chaos that charms and humors the audience rather than overwhelms them, as well as maintaining a joyous absurdity in its conception as a whole. We are not meant to question why a gila monster growling and snarling deserves a disclaimer when we, the audience, have been subject to the thrills of amphibian suicide minutes prior without any sort of warning—we are only meant to laugh at it.

While Avery could have ended the segment there on good footing as is, he continues to take it one step further. When the gila monster literally breaks boundaries by overlapping the separation line and snarling directly at the girl, the toddler politely douses the reptile with a hearty dose of its own medicine, the same exact Blancanese vocals used for her growl and all.

Our last look at the hideous fiend is a degrading one as he barks and whines like an injured puppy into the horizon. All in a day’s work.

“Now to the Grand Canyon of Arizona.” Johnsen’s illustrious paintings and overlays make a confident support for Marcelle’s orations: “It is indeed a breathtaking panorama of multicolored rock.”

A little over 10 seconds of complete silence (save for the music score) allow the audience to digest the gorgeous paintings for themselves. Seeing that this follows scenes whose paces were much more irreverent or brisk previously, the grace period is necessary, relaxed, feels earned and leisurely rather than an attempt to pad out the time. Having genuinely striking background paintings worthy of the audience’s attention certainly aids again in the intent of being enamored by the naturalistic splendor.

“Here, from this point, the massive walls of the canyon are able to throw back an echo from a distance of 3 miles! Let’s listen to this tourist.”

Portly tourist obliges dutifully to the narration, heaving a “HELLOOOOOOOOO!” in to the abyss of the chasm. Wonderful coloring and discrepancy in value between the light, golden tones of the ledge to the deep, dark, rich purples and blues of the canyon’s shadows. That, paired with the tourist and ledge being placed on a separate layer than the background, continues to encourage and evoke special relations and a naturalistic, tangible depth to the environments. Likewise, the differences in lighting and color easily guide the eye of the viewer to the tourist.

His “HELLOOOOOOOOO” is, peculiarly, unreciprocated. Complete silence in the music score make his attempts feel even more isolated, the lack of a response even more strange.

A second bellow goes unreceived as well.

His final bellow—now an ear-splitting, microphone gain inducing shriek thanks to Blanc’s ever reliable vocal chords—does get a response, a student of the comedic rule of threes…

“I’m so-ree-uh! They do not answuh!” Sara Berner imitates the likes of a floaty operator, a role she would occupy quite regularly. Reverb and echo on her deliveries truly sell the gag, still grounded to the echo themeing but abstract enough to call attention to itself and successfully subvert expectations.

Flabbergasted tourist engages in a series of signature Avery takes to ensure that he has been rightfully subverted.

Yet another visit from the “determined dog” in the narrator’s own words indicates that a resolution for his story is imminent. Winding perspective and elaborate camera pans continue to uphold audience interest and animated appeal, particularly when the perspective changes from a wide shot to an overhead view of the dog descending down the rocky slope and continuing forth. “California, Here I Come” continues to blare triumphantly to match the dog’s journey.

Upon some more gorgeous paintings—this time of the Colorado River—the camera fixates on a hoard of beavers building a dam. Varying perspectives as the animals swim in and out of frame at different intervals sustain a natural yet syncopated rhythm, maintaining spontaneity in their movements. A cross dissolve and pan outwards hints to bigger and better things.

Yet again, Avery succeeds through his embrace and delivery of caricature. Not only are the beavers constructing a fully fledged, manmade dam a funny and effective subversion in itself, but the manner in which they move, like drones sliding up and down the screen as mechanically as possible to produce the dam clinches the mischievous impossibility of it all. Obscuring the structure through a dust cloud would be serviceable in itself, but the blatant disregard for physics or logic here almost make the delivery a more rewarding experience than the punchline itself. Unapologetic and confident in its oxymoronic nonchalant extravagance.

Dissolving back to the determined dog from before, the shift in perspective and tone—much more intimate, personal as well as tired and defeated—indicate a resolution is finally on the rise. Marcelle continues to display great admiration for the pooch’s determination.

The state line dividing two entirely different ecosystems harkens back to a synonymous transition in the similarly named Detouring America. Fido displays a shred of humanistic sentience as he pauses to read the sign for himself, eyes scanning each line of text just as he did upon spotting the first landmark all the way back in Alaska. His exuberance is shared by the narrator, disclaiming an incredulous “Ah! He’s made it!”

More running pans ensue, now with the aid of typography. To Avery’s credit, the repeated running sequences certainly don’t feel as tedious as they could thanks to being exposed in brief, to the point bursts, all unfurling in a different landmark. Here, the audience now has the added benefit of typography and newfound speed that would be another keystone for Avery through its promptness and exaggeration—in no time flat, the dog darts through a variety of Californian landmarks, camera slowing down only briefly to ensure the audience can digest it quickly enough.

At last, we arrive to the bonafide center of the dog’s attention: the ceremoniously labeled “BIG TREES”.

Such sparks a dopey yet impassioned monologue from Blanc, yet again gifting the dog a humanity hardly granted yet through the gift of speech. While his curiosity and determination to head to California separates him from the pack as is, there was hardly any indication that he could talk or walk—much less monologue about “thousands and thousands of trees”.

So overcome with the prospect of relieving his bladder on every single tree for himself, the dog is reduced to a sobbing yet victorious mess as we iris out. Knowing Avery and his sensibilities, the punchline doesn’t come as a surprise and is instead inspected, but that certainly doesn’t make it any less endearing. Such laborious buildup ensures a satisfying—if not self aware—end, and one can certainly get the impression that Avery was likely satisfied and humored by the outcome.

If Cross Country Detours isn’t Avery’s best travelogue, then it certainly is one of the best. Coherent, cohesive, inspired, chipper, mischievous, shocking, foundational and funny, Detours stands out among its cohorts through the aforementioned qualities.

Such a long runtime at nearly 10 minutes sounds disastrous, especially when met with something as instinctively groan inducing as another measly travelogue. Instead, whether a mandate or a symptom, Avery makes effective use of his time. Sequences are strategically arranged to feel memorable and distinct from one another, balancing long scenes with short ones, shocking with pleasant; the elongated runtime allows Avery to resist the urge to rush a joke through and instead milk it for all its potential, at times testing the audience’s patience but never straying over the edge. Short jokes aren’t overstuffed with awkward pauses to meet a quota, long jokes are allowed to thrive and have room to breathe. While Avery’s timing and speed is already succinct as is, it is here where he seems to be in his element the most.

Indeed, an anomalous consistency prevails throughout the entire cartoon. Many of Avery’s travelogues are often categorized through their highs and lows, remembered for one particularly funny gag but not the full array. While Detours has its own standouts (primarily the frog and the lizard, both due to their respective brazenness), there doesn’t seem to be any sort of single “bad” or uninspired gag in the film. Cornier jokes such as the bridge in Bryce Canyon or, again, the frog, are rescued through their self awareness, and even gags that are mere repeats—such as the bear berating the tourist or the implication of the dog’s doings with his trees—are nevertheless fresh and endearing through changes in delivery or a general chipper execution.

Striking such an effective and successful balance as sharp as this one is rare, especially for someone as prone to inconsistency and unevenness as Avery. If all of his travelogues were this focused, this inspired, this finely tuned, who’s to say how much further his rapid development as a director and comedic mastermind would have accelerated. To think that the majority of the travelogues to predate this falter comparatively is almost too disappointing to mull over. Nevertheless, this is a brilliant cartoon and a great example of just how brightly Avery can shine when in his element. An anomaly in its consistency and one that is able to appreciated more through its rarity.

No comments:

Post a Comment