Disclaimer: This review entails racist content and imagery with the intended use of historical and informational context. I ask that you speak up in the case I say something that is offensive, harmful, or perpetuating so that I may take the appropriate accountability. Thank you.

Release Date: March 30th, 1940

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Friz Freleng

Story: Ben Hardaway

Animation: Cal Dalton

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Arthur Q. Bryan (Elmer, Major's Aide), John Deering (Narrator), Mary Shipp (Crimson O'Hairoil), Sara Berner (Topsy), Mel Blanc (Colonel, Slaves, General, Hugh Hubert, Paul Revere), Jim Barron (Radio Announcer), The Sportsmen Quartet (Chorus)

(You may view the cartoon yourself here.)

After a little over a year and a half at MGM, a discontented Friz Freleng returned to the Schlesinger studio in April 1939 to take back his unit. It would be one of the best decisions made by the studio—his second tenure at Warners would be much more successful, long lasting, and, most importantly, funny. Having been on board since the conception of the series, Freleng would be only one of three directors to direct all the way into the ‘60s. Even after the final closure of the studio, he would partner with David DePatie to lease the former studio and produce shorts until acquisition by Seven Arts in 1967. DePatie and Freleng would find more success elsewhere producing independent shorts for their own company, most notably the Pink Panther cartoons. Freleng’s return to the studio in 1939 was not just a phase, but a permanent investment.

Instances of usurping the Hardaway-Dalton unit are present through the credits alone. Indeed, while Freleng receives the director’s credit, Hardaway’s influence in particular is still as potent as ever, indulging heartily in obvious puns, wordplay, self indulgences and the like.

Produced during the Gone with the Wind craze, Freleng’s first cartoon upon his return is a burlesque. Scarlett O’Hara is thusly caricatured as the unsubtle Crimson O’Hairoil, whereas Rhett Butler receives the new title of Nett Cutler—played by the ever enigmatic, certifiably Clark Gable-esque Elmer Fudd. Recycling his design from Elmer’s Candid Camera, his use from another director (never mind a “new” director) indicates a desire for permanence with the character.

John Deering returns from Old Glory to provide the rich vocals of the narrator. Even before the fade in from black comes to a complete rise, Hardawayisms are forcefully shunted in the face of the audience—a literal depiction of the self described bluegrass country has his influence all over it.

Likewise with Deering’s establishment of the setting: “It is the year 1861 B.C.—Before Seabiscuit.” Reeking again of Hardaway’s influence, such obvious and plain unfunny wordplay (that requires a stretch to even succeed) is not of Freleng’s nature. Freleng prioritized subtlety, nailing his comedic timing down to an exact science through even the visual slightest manipulation. His humor is comparatively more modest than Hardaway’s, but so is everyone else’s on the planet. Instead, the audience is meant to be charmed through the faux multiplane visuals of literal bluegrass and cotton fields. Indeed, through the longevity of the foreground overlays and pans alone, a certain visual prestige is gifted a priority to both assert the idyllic tone and juxtapose—if not distract—from the cornpone writing.

Upon settling on one Colonel O’Hairoil’s mansion, the background painting shifts abruptly—trees in the background suddenly disappear as the painting is exchanged for one that is identical to accompany the camera truck-in. While it certainly isn’t a glaringly obvious issue, the disappearance of the trees does cause the picture to jump and jostle the momentum orchestrated by gliding camera pans.

Ample use of foreground overlays continue to establish a certain prioritization in the art direction and the intended serenity as the camera pans along the interminable veranda. Formal introduction of our Colonel continues to engage in Hardawayisms, his skin blue to match Deering’s description of “a true, southern blue-blood.”

While the imagery in itself is fine—a respectable amount of dedication exercised in maintaining the gag seeing as he’s blue for the entire film—Hardaway’s input continues to permeate as the colonel sings a few somewhat incomprehensible bars of “Am I Blue?”. Such blatant disregard of subtlety is again much easier to pin on Hardaway than Freleng.

Even further indications of Hardaway’s influence is a somewhat subtle but apparent cribbing of previous episodes. Deering asking the colonel to introduce himself is synonymous in tone to the opening of the much more effective and amusing Uncle Tom’s Bungalow—upon asking about his tobacco plantation (despite very clearly depicting rows of cotton fields that would soon be highlighted in an approaching song number), the colonel subverts the audience’s expectations by reciting the Lucky Strike auctioneer slogan. Nothing more, and certainly nothing less.

On the topic of Uncle Tom’s Bungalow, the name of the cartoon itself serves as a riff as the tone takes an odd change. An idyllic camera pan comes to a halt to ensure the audience truly grasps the gag—more Hardawayian spoon feeding—before resuming to accompany a song number.

Said song number is “Old Black Joe” sung by an off-screen chorus meant to invoke the singing of the slaves—indeed, it would be foolish to expect a cartoon with “Confederate” in the name to be exempt from grotesque caricatures and stereotypes. Vocals are harmonious and pleasant as always, and the stoicism of the animation is admittedly quite refreshing when juxtaposed against the previous barrage of corny, self-serving gags, but is nevertheless uncomfortably by proxy.

Freleng’s own directorial influence begins to make itself more apparent, as the gag of one man mowing a line of cotton that collects into a bag behind him is reused from Freleng’s Goin’ to Heaven on a Mule from 1934. While Hardawayesque tendencies continue to persist throughout, they are most concentrated in the beginning—it seems likely (though pure speculation) that the short began production as a Hardaway/Dalton effort that was later handed to Freleng for completion upon his return to the studio, hence Hardaway and Dalton both receiving credits for their own respective departments.

Likewise, a wholly patronizing gag of a Stepin Fetchitesque caricature warning a kid not to get “too ambitious” by putting two balls of cotton in his hand feels more akin to Freleng’s sense of timing, the glacial movements purposeful more than accidental. Its delivery at the very least doesn’t feel nearly as patronizing in terms of its conspicuousness—just in terms of racism.

A fade to black indicates a segue to other endeavors. Thus marks our introduction to Crimson O’Hairoil, her first impression made by her off-screen and wryly scandalous retrieval of her bloomers from the clothesline. The sly tone and dynamic upshot of the mansion yet again appeal more to Freleng’s vision than Hardaway’s; while the entire cartoon is bogged down through its premise and offensive stereotypes, Freleng’s presumed regain of control at least paints a somewhat more tolerable picture—easier to stomach such a premise when the deliveries actually have some semblance of confidence and humor behind them rather than forced, fragmented quips.

“Crimson was born with a silver spoon in her mouth.” Tex Avery would reprise the same gag of dutiful obedience to the idiom in his Symphony in Slang, an entire cartoon dedicated to that same shtick. To cement that the spoon is more than a manifestation of a phrase, Crimson talks with the spoon right in her mouth, rendering her words completely incomprehensible—at least until she takes it out of her mouth to repeat herself.

A wide shot of a girl helping her get ready is nevertheless transparent in its own attempt to get laughs through her looks and minstrel dialect, not adding anything of value (much less a punchline.)

“Crimson had many admirers who came from far and near to seek her hand.” Comedic anachronisms now manifest through a parking lot situated outside the mansion. While the mere concept of people parking their horses in the confines of a parking space is amusing in itself, further attempts to cement the gag serve through a sign advertising the rates for the lot.

Hardawayisms eke back into the writing through Deering’s narration (“And of all the suitors who sought her hand, no suitor suited her,”) but are thankfully pardoned through appealing—if not at times sardonic—character acting from both Crimson and the suitors in question. Particularly, the comically dejected, slumped over walk each man is subjected to after every haughty rejection. Ditto for the rhythm and spontaneity in which they appear, as though manufactured from thin air. Repetition establishes pattern, which establishes familiarity and therefore coherence.

A bit of dissonance between narration and on-screen happenings does somewhat skew the momentum; while the audience is met with more parking gags (this time, all of the rejected men lugubriously accept their validated parking tickets), Deering prattles on about one particular suitor that does capture Crimson’s attention. Such a dissonance allows the reveal of “that chivalrous, that hard riding, square shooting soldier of fortune — Nett Cutler!” to revel in momentary suspense and buildup, which is certainly beneficial in itself, and the disconnect again isn’t so much a detractor as it is an attempt to squeeze more gags than perhaps necessary in a short amount of time.

Spontaneity nevertheless works in the favor of Cutler’s reveal, for we are met with the certifiably unchivalrous Elmer Fudd. Much like Arthur Q. Bryan’s vocal debut in Dangerous Dan McFoo, an amiable “Hewwo,” from Fudd asserts everything one needs to know about this “soldier of fortune”.

While Elmer’s design is derivative of his appearance in Elmer’s Candid Camera (the only difference being a change in suit colors), there is a certain fascinating peculiarity behind his introduction. In hindsight, the familiarity of his “Hewwo” is a standard gag and one that is always amusing through deliberate juxtapositions in expectation and reality, as we are granted with here.

However, it becomes intriguing to remember that Elmer’s Candid Camera hadn’t been released upon Confederate Honey’s conception—there was a certain gamble involved seeing as it was unknown how audiences would react to the character. Assuming this cartoon first entered production in or around April 1939 when Freleng returned to the studio, then even Dangerous Dan McFoo, the first short to feature Bryan, hadn’t yet released either. While the success of the joke here is not wholly reliant on Elmer’s status as a character—rather the incongruity between the narration and reveal—it is certainly insightful to review with the aforementioned hindsight, as his character status does generally make the joke seem even more established, familiar, and so on.

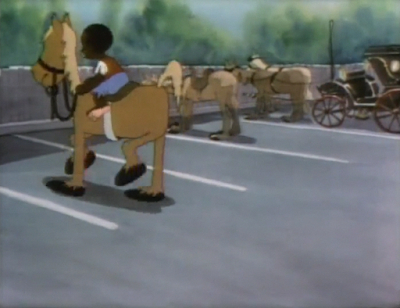

More intriguing than the particulars is the run cycle of the horse. A fantastic caricature of motion that would continue to be expounded upon with even greater exaggeration in future cartoons, the horse hardly moves, pose remaining rigid but bouncy as his legs do all the work by taking a gallop to the extreme. Compare this to the run cycle in Buckaroo Bugs, animated by Manny Gould—Gould’s is more exaggerated and fluid, but that we have even broken this level of caricature at this point in time indicates that growth is ever evolving.

Likewise with his halt. Upon Elmer’s command to stop, the horse merely switches from one extreme key pose to the other with absolutely no in-between drawings (save for a very brief cross dissolve that could easily be mistaken for interlacing and vice versa—seeing as the print doesn’t have any other persisting examples of interlacing, it seems to be purposeful.) Elmer’s torso reverberating back and forth through the aid of liberal dry brushing effects speak for the shift in momentum itself. Succinct timing that is native to Freleng’s directing, and certainly a relief when compared to the timing in Hardaway’s shorts; a complete antithesis.

Derogatory caricatures persist as Elmer literally hands the reigns over to a jockey, promising he’ll be “wight back.” If there is any benefit to be had, it’s the continued exaggeration in the animation. Car metaphors are abided by as the jockey maneuvers a three-point turn into the parking spot—car engine sound effects, purposefully mechanic fluidity in motion and general caricature in the horse’s legs effectively support the metaphor.

Dick Bickenbach provides animation of Elmer’s introduction to Crimson, and shows no inhibitions at being guided by a new director. Outside of the telltale eye blink lines, which add plenty of personality in themselves (successfully conveying Elmer’s meek bewilderment upon Crimson’s sudden insistence and clear infatuation with him), but posing is also taken to new extremes as Crimson ends up towering over our hero. Very solid lines of action in both characters, great silhouettes, keen awareness of negative and positive space all swiftly establish a palpable energy and solid power imbalance that render both the characters and scene very dynamic and engaging.

Before Elmer can finish wooing his mistwess, the telltale whistle of a bomb from off-screen interrupts both of them. While the disparity between the whistle and the actual explosion lasts a beat too long, attempting to convey the unseen distance of the explosive traveling, the brief pause dedicated to both characters staring at the audience as though they might be responsible or have a clue is a subtle yet solid piece of character acting, fitting in its somewhat subversive commentary.

Dynamic brush strokes and action lines indicating the shake of the blast are an appealing graphic touch as well that gives the characters a stronger sense of motion and humanity. Especially when our chivalrous soldier springs into Crimson’s arms and cradles her in an act of Fuddish cravenness; again, great silhouette on Elmer in particular. The size and design disparity between the two enable plenty of room for sight gags and commentaries that most certainly wouldn’t have been thought of or delivered under Hardaway’s direction.

“Then came the war!” A dissonant bugle call as a brawl is summoned right out of thin-air facetiously supports the narrator’s statements.

Sure enough, a cinematic but somewhat straightforward shot of Confederate soldiers marching in perspective to a bold accompaniment of “Dixie” indicates a call to arms. Staging and atmosphere is nice, the pink of the sky color a nice dynamic, moody touch, but the vague designs of the soldiers do little to spark excessive visual interest.

Comedically drone-like in his jingoistic obedience, Elmer attempts to assert his chivawwy by “join[ing] the wegiment.” Vestiges of his prototype self are evident in the manner in which he departs—a purposefully abrupt jump and twirl into the air before waddling out of view with the utmost, simpleton urgency. Such flighty, almost inexplicable caricature to such motions were typically unique to his early prototype, which certainly makes it fascinating to see such humorous rigidity in a more evolved form. Such a departure wouldn’t seem out of place in a Tex Avery cartoon—just replace Bryan’s monologue with Danny Webb’s Joe Penner impression, and you have a distant cousin to cartoons such as Cinderella Meets Fella.

Crimson, of course, is smitten, “My hero” clichés coyly deployed.

Prototype tendencies do grow a bit stilted in a shot of Elmer running out of the mansion and scrambling aimlessly in mid-air. While successful in depicting a mindless, inept yet exuberant call to arms, a presiding vagueness somewhat hinders the delivery—particularly his arm grasping out in the air for no discernible reason. Nevertheless, his intentions are clear and concise, and the departure is more amusing than not.

A brief spotlight on the jockey telling Elmer he forgot his horse seems too conspicuous to stand on its own. Indeed, it hints at forthcoming gags involving Elmer’s equine negligence.

Romantic endeavors serve as a stronger priority. Crimson promises to burn a light in the window for her precious Nett…

…who reciprocates her waves after hopping into the backpack of one of the soldiers. While the movement itself is a bit stilted, the general idea of Fudd’s ineptitude is unhindered. Truly a shining example of chivalry and stoicism.

With a fade to black and back in comes a barrage of Civil War gags, many of them strong with Hardaway’s gag sense. Namely the lone Union soldier striking the war and pinning it as unfair.

Same goes for the union suit gags.

And the jowl-flapping speech patterns of a hulking Union general. And his seemingly interminable monologue. Blanc’s vocals are spirited, Stalling’s accompaniment of “The Battle Cry of Freedom” providing some pleasant listening, and brief cameos of Melvin “Tubby” Millar, Henry Binder, Ray Katz, and Paul Smith certainly add novelty from a historian’s perspective through recognition. However, Hardawayisms begin to weasel their way back in through mentions of The Cotton Bowl or referring to Stonewall Jackson as a southpaw. The sports metaphors feel somewhat vague and ambiguous, unsupported by coinciding visuals and suffering from a general lack of commitment.

Instead, the most “sporty” gag involves the soldiers dogpiling on each other to scavenge the general’s discarded cigar. Even then, its primary sports connection stems from recognizing a similar, more committed gag in Tex Avery’s Screwball Football where the players fight over the coin from the coin toss instead. Hardaway’s influence looms over the sequence more than Freleng’s.

However, the cinematography on the following shot of cannons firing is definitely a subject to Freleng’s directorial tendencies rather than Hardaway’s. Such elaborate lighting effects, varied camera angles, fast cutting, and sharp musical timing through sound effects would never be caught dead in a Hardaway short. Freleng’s understanding and embrace of cinematography cannot be understated in the relief it brings succeeding the Hardaway and Dalton cartoons.

A bugle call turning into an impromptu jazz number, however, would be caught dead in a Hardaway and Dalton short. Contradictory in tone to the theatrics of the cannons firing, dedication to the shtick is at least admirable, the unconventionality highlighted by having the musical score consist purely of the bugle and drum set—no orchestration to back it up further.

A random appearance of a Hugh Hubert caricature can be chalked up more to Freleng, if only because of its connection to The Hardship of Miles Standish—another Freleng directed short featuring the fledgling Fudd in another historical lampoon that stars caricatures of Hugh Hubert and Edna May Oliver.

Hubertisms lost on modern audiences persist, particularly through his rambling refutations of his own statements (“All wires down from Richmond, Major.” “Hoo hoo hoo! That’s good, that’s good, good. Oh, no, no, no! That’s terrible! Terrible, terrible.”) If anything, novelty persists through association and knowing that Daffy’s own iconic hoo-hoo laugh is based upon Hubert’s.

Back to Elmer, who is now an official Confederate soldier. More vestiges of Dangerous Dan McFoo’s influence manifest through pinball metaphors. Soldiers gather around Elmer like cronies at a bar, one even motioning for him to pull the lever on the cannon back further. Despite the movement and spacing being a bit too quick and flighty, the subtleties in acting—hand motions, various glances, little pauses—deliver a welcome richness, if only slight.

Pinball symbolism continues to be embraced through the resolution; instead of the shelling exploding and prompting a series of metaphors after the blast, an explosion is absent all together. Colorful lights blink over the horizon instead, touting a respectable dedication and completion to the gag.

Same for the flashing neon lettering of “TILTED”.

A dissolve to the jockey still waiting in the parking lot with Elmer’s horse cements earlier notions of his presence leading to a running gag. Egregious and hindering as the jockey’s design is, props are to be had for successful storytelling through environments alone; no lines of dialogue or witty glares at the camera are needed to establish that they’ve both been waiting for a long time and will continue to do so.

Our seemingly forgotten Colonel makes another appearance, anachronisms still joyful in their persistence as he gets a play-by-play of the war through the courtesy of a radio.

Upon learning of a victory from “the Yanks”, the Colonel wastes little time engaging in a fit. A fit appropriated from the Billy Bletcher voiced hotel manager in Egghead Rides Again—the Colonel’s copious “dadburn”s lack the charm and novelty of the former, trying a bit too hard to be funny and not naturalistic enough in its intent.

However, no matter how obscured by the impending fade to black, posing on the Colonel is limber and appealing—particularly when he crosses his arms and settles into a pouting position.

A quick attempt to garner pathos through Elmer’s lovelorn sighs at a photograph are interrupted through a colorful blast in the distance…

…that reprises Freleng’s “Eat at Sloppy Joe’s” gag from Plenty of Money and You, which was the first gag of that kind in a Warner Bros cartoon.

On the topic of reprisals, Crimson lives up to her word of burning a light in her window; the visual of a spotlight illuminating the darkness is a take-off of the same gag in Tex Avery’s I Wanna Be a Sailor. Here, the visual has the added benefit of perspective—a white color card very briefly fills the entire screen as the light rotates, immersing and integrating the audience into the film.

Unlike I Wanna Be a Sailor, the gag leeches into a vague, aimless, unfunny tangent that truly can only be the mastermind of Hardaway at work. Animation reused from Old Glory (fitting with Deering’s involvement in both films), rotoscoping is somewhat altered to accommodate the lighting as an anachronistic Paul Revere cameo more ill-fitting than funny bellows about the impending arrival of the British. Blanc’s effeminate “…with a bang bang,” is amusing, but not out of true comedic potential—rather, amusing at how comedically out of place the vignette is, not to mention how it contradicts its own dramatic setup. A Hardaway tradition.

Such corny gags cannot be lingered on forever. To establish the passage of time, a montage of overlaid footage ensues. Nothing groundbreaking or as gripping as Frank Tashlin’s montages, the depiction of the calendar tearing its pages off with each passing year is nevertheless informative and creative.

Freleng and company expound on Elmer’s horse negligence by returning to the jockey, parking lot thoroughly covered with weeds. It’s a short spotlight, but one that doesn’t overstay its welcome and provides amusing and coherent connective tissue. The calendar overlay succeeding the visual wraps the entire sequence in a solid bookend.

At long last, the war comes to an end (even if the calendar is 10 days after Lee’s surrendering.) Thus, the first order of business is purposefully cloying saccharinity to indicate peace and harmony—such manifests through songbirds making nests in the empty cannons, wagon wheels intertwined with a polite smattering of flowers.

Recycled footage of the soldiers coming home establishes yet another bookend to the story and film rather than an act of complete laziness. That the reused animation spared a few extra bucks was just another incentive.

Likewise, the flame on a mutated amalgamation of candle wax finally blows out in Crimson’s window—an act of finality, if not impatience.

Impatience that is further supported through a cross dissolve to Crimson herself. Rigid foot tapping is succinct in its message, succeeding through its minimalism and curt movement.

A patch on the back of her dress is a bit less funny in its conspicuousness—perhaps due to an innate tendency to compare such cornpone humor to the likes of Hardaway—but nevertheless a successful juxtaposition to her prim and proper looks.

Nevertheless, a quick succession of knocks timed to “Shave and a Haircut” put Crimson’s haughty pacing to a halt.

“It was Nett!” Proto-Fuddisms continue in the delightfully unchivalrous grin Elmer bothers to spare for a few seconds before reverting back to his vacant gawking. Fantastic comedic timing and that succeeds through its minimalism, allowing mannerisms and facial expressions to speak over any witty remarks. Little subtleties such as these are of Freleng’s greatest comedic strengths.

Now, Crimson and Elmer resume where the war had cut them off. Crimson continues to loom over her befuddled knight in shining armor, who continues to flounder in whichever question he struggles to ask.

A close-up shot of Crimson looming over Elmer asserts a finality through its purposefully uncomfortable tightness—Elmer can’t lean back any further without dipping entirely out of frame. A confession of utmost love is on the horizon…

“”Wouwd you vawidate my ticket?”

A brief grimace from Elmer as he awaits Crimson’s response perhaps identifies Cal Dalton, fittingly enough, as the presumed animator; that same tight lipped expression serves as an easy identifier for his work, especially with how high Fudd’s facial features are on his face.

Request denied as we get one last look at our chivalrous hero.

Confederate Honey has a tendency to feel like a diet Hardaway-Dalton cartoon more often than not. Such a feeling persists not even through the writing, but the directing—some scenes feel much more coherent and focused, confident than others, whose looseness and vagueness speak more to Hardaway’s influence. While it is never as black as white as “Freleng had full influence over this, whereas Hardaway had full influence over this” (and my theory of Hardaway potentially starting the cartoon is pure speculation rather than absolute fact), it is easier to identify the sensibilities of each director through recognition of their habits and patterns. Especially directors such as Hardaway and Freleng, whose approaches differ vastly.

Though racist caricatures are grotesque and inflammatory, the premise of the cartoon as a whole coming as a detriment, Confederate Honey isn’t necessarily awful; the bits that are more Frelengesque in their timing and aren’t burdened by racism are salvageable, such as the run cycle on the horse, the posing on Crimson looming over Elmer, and Elmer’s joyously stupid grin towards the end of the film. Bursts of cinematographic embrace are peppered throughout the short, the cannons firing being of particular note.

Regardless, the story at times feels incoherent and vague thanks to Hardaway’s writing. Self indulgent vignettes such as the Paul Revere cameo are ill fitting in a way that is confusing and hindering more than humorous, the barrage of corny wordplay in the beginning is borderline insufferable and provides a glimpse of what the cartoon would look like had it been under the full control of Hardaway, and both Elmer and Crimson have a tendency to feel underutilized.

One can sense Freleng attempting to work around the limitations wrought by Hardaway, but not to great success. Baggage of the film’s premise already pegs it as a cartoon that is less than desirable, but even outside of that there just isn’t much to the film. Of course, despite the premise (much less the name), that didn’t stop Nickelodeon from airing the cartoon with all of the scenes involving the slaves excised. Outside of the running gag of the jockey waiting for Elmer, which is clever through its environmental storytelling, nothing of value was exactly lost… but nothing of value was exactly gained, either.

Not the most inspired of homecoming cartoons, but many of the issues again can be attributed to the involvement of Hardaway more than Freleng. Once free of Hardaway’s influence, Freleng would quickly ride to a steady tenure of inspired and genuinely laugh out loud funny cartoons that would continue for decades to come. Already, patterns that would make his films so successful can be seen in this short through little glimpses, particularly in character acting.

While Freleng was absolutely a competent and fine director in his previous Warner tenure, he did somewhat turn into an underdog when matched with the likes of Frank Tashlin and Tex Avery (and later Bob Clampett.) Not that his cartoons were outright bad—excluding Jungle Jitters which, even outside of racist stereotypes, has the prestige of being one of the studio’s worst cartoons period—but he did pale in comparison for a short time next to his cohorts.

Thankfully, even in spite of this cartoon’s pitfalls and hinderances, the more Frelengesque bits already display substantial growth since his absence. A more tangible feeling of coherence, control, understanding of how to evoke laughter and humor from succinctly timed gestures, and general sense of added experience prevail. Perhaps that’s coming from the pure relief of Hardaway’s directorial departure, where any cartoon looks like a miracle compared to his filmography, but there is a bright future ahead for Freleng—even if he wasn’t able to fully indicate that here.

.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment