Disclaimer: This review contains racist content and imagery presented for historical and informational context. I ask that you speak up if I say something that is harmful, ignorant, or perpetuating, as it is never my intent and I seek to take the appropriate accountability. Thank you.

Release Date: February 10th, 1940

Series: Looney Tunes

Director: Bob Clampett

Story: Tubby Millar

Animation: Vive Risto

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Porky, Ali-Baba, Bomber, Horn, Blondie, Gas Attendant,)

(You can watch the cartoon for yourself here.)

Cartoons involving flagship characters as legionnaires have been a time honored tradition at Warner Bros. Beau Bosko, Buddy of the Legion, even Porky once before in Little Beau Porky. Ironically enough, Melvin “Tubby” Millar, most associated with his writing work under Frank Tashlin, marks his first collaboration with Clampett on this very short. He wouldn’t stick with Clampett long, only writing about 7 cartoons with him total, but the distinction is important enough to note.

While Little Beau Porky was released in an era where writers went uncredited, it wouldn’t be a surprise to discover that Millar wrote the story for that short too. While pure speculation and nothing more, Ali-Baba Bound does tout a number of similarities through concepts, gags, or general composition. Adopting a tone that prioritizes mischief over theatrics, we follow Porky’s pursuit in fighting off Ali-Baba “and his Dirty Sleeves”, literally holding down the fort while the remaining legionnaires attend a convention.

Unsurprisingly, the first minute of the cartoon crams in as many Clampettisms as possible. Puns, time consuming title cards, bloated establishing pans, still shots, and a song number all seek to pad out time and provide a comfortable transition into the story. For the benefit of the viewer, the typography on the title card establishing the setting as the Sahara Desert is appealing, bold, solid juxtaposition in fonts, neon lights strung on palm trees are another polite antithesis, and wordplay between The Brown Derby and The Brown Turban is at least serviceable and playful. A sign proudly touting “UNDER NEW MIS-MANAGEMENT” would reappear in Porky’s Poor Fish—also written by Millar.

Our song number is, in a twist, sung by Porky himself rather than a saccharine chorus courtesy of The Rhythmettes. In this case, a chorus of “The Girlfriend of the Whirling Dervish.” Curiously, Porky’s vocals are not only unsped, but hardly obscured by a stutter as well. He only trips up on one word in the entirety of the song—that the deepness of his vocals feels more uncanny than the lack of a stutter only asserts how his personality and role are independent of the impediment. When written correctly and consciously, the stutter is an accent to a founded ensemble rather than a crutch or disguise.

Visuals accompanying the song are seldom flashy, consisting primarily of Porky strutting along the desert through the aid of his signature double-bounce walk. As such, the camera pans to default on a caricature of George Raft, renowned for his role in gangster films in the ‘30s and ‘40s. All seems as unassuming as a Hollywood caricature standing in the desert can be (albeit some trouble on the animated smoke trails from his cigarette, briefly sliding into place from mid-air due to the camera pan)…

…until we pan down to reveal him nefariously flipping a coin with his foot, referencing his role in the original Scarface. A surefire sign that mobster shenanigans are afoot.

Such a sighting puts Porky’s song number to a screeching halt, startled by the additional company and engaging in a series of wordless takes; hat takes, scrambles, blinks, a gulp—pointing a finger towards himself in a wordless gesture that reads “Me?” is a bit out of place seeing as the Raft caricature never seemed to explicitly beckon him forth, but nevertheless indicates Porky’s newfound attention and obligation to his new guest. Anxious, almost guilty side steps are a nice indicator of his hesitation.

John Carey’s acting for both characters is—unsurprisingly—more sophisticated and clear as he takes over the animation for the next scene. Porky is cute and appealing as always in his drawing style, honing in on his innocence through wide-eyed stares and open mouthed gawks.

Likewise, intricate acting on Raft, whether it be as subtle as a furtive glance towards offscreen and the quick flick of an eyebrow or granting a comparatively more sculpted, detailed head tilt on his “Shhhh!”, all read as a borderline jarring juxtaposition against the flat stylization of his profile. He was designed by caricature artist T. Hee for Friz Freleng’s The CooCoo Nut Grove in 1936, meant to look and feel like a flat drawing—the life and intricacy Carey gives him through such gestures makes for a surprising contrast, but one that is welcome and fascinating rather than truly uncanny.

Rather than unveiling a note for Porky in the sanctity of an inside pocket, Clampett and Millar embrace joyous impracticality through a much more obtrusive “take one” box. The secret message rightfully being labeled as such ensues no such privacy is given, furthering the reigning conspicuousness.

Though the construction and general solidity is a bit off, layouts are inventive as Porky grabs the note in diagonal, foreshortened perspective. At the start of the scene—hooking up to the previous one—he’s closer to the foreground, taller, before leaning back and reading the message for himself. A very subtle maneuver but one that is just as sneaky as his impish side-eye to Raft, cautioned right before delving into the contents of the note.

A cute, endearing acting choice that is oxymoronic; small as the gesture may be, it speaks playful volumes and almost feeds into a polite sense of self-importance and imitation. Squat, diminutive, and naïve, Porky isn’t a character that gives off a strong impression vouching for his status as a legionnaire—it’s as though the side-eye is a means of proving himself, that he’s being fed secret messages, and this is a normal reaction spies have when receiving such confidential information and absolutely not something he picked up from watching a movie. All of that is inherently furthered through the presence of the certifiable movie star George Raft.

Shifting focus on a sign, letter, or note often entails a shift in focus to wordplay and puns; all of which are plentiful upon a close-up shot of the note. The 1939 film Confessions of a Nazi Spy is referenced in the heading, Ali-Baba and his Forty Thieves are rebranded as his Dirty Sleeves (homonyms between Dirty and Forty a bit of a stretch), and punnery on the phrase “tattletale gray” (which gained notoriety through advertisements for Fels Naptha soap) first heard in Jeepers Creepers serves as the name of the tipper.

Speaking of, Porky’s exclamation of “J-ee-jeepers creepers! I’d better hurry,” is somewhat antithetical in its animation; while the “jeepers creepers” is delivered on a polite head bob cycle—fine in itself—the stagnation in his follow-up delivery is a stark contrast to the arm flailing, note throwing, aimless scrambling histrionics that ensue. An overabundance of energy isn’t the worst problem to have, but doesn’t make for very believable acting when divorced from the vocal intonation.

Regardless, the story and intent of Porky’s mission are clearly established, which is arguably more important than animated nuances. In a maneuver channeling the pacing of Tex Avery, Porky darts offscreen only to return and tip his hat. Clampett’s adoration of pop culture references continue to weasel their way into the cartoon as Porky imitates the likes of Joe Penner: “Thanks, you nnnnnnnaaaach-sty spy!” Props to the animators on his prompt exit, maintaining spontaneity in momentum rather than hampering it.

On similar critiques of discrepancies between voice acting and animation, Porky’s lip sync—or lack thereof—following his punny, Clampettian line of “And I thought Ali buh-bih-Baba and his Dirty Sleeves were all weh-washed up!” is hardly timed to the vocals. Instead, it’s an aimless talk cycle paired with an equally aimless walk cycle that feels uncanny and unsyncopated. Fitting for a naturally off-kilter character like Daffy, not so much for a more grounded persona like Porky’s.

All of the above are synonymous to the perspective animation of his entrance in a camel themed take on a rent-a-car lot. Pacing on the double bounce walk reads as jittery and unsteady rather than comedic and secure in its eccentricity; a lack of a balanced center in Porky’s weight makes him seem to glide across the screen like the moving series of cels he is rather than a living, breathing character.

Nevertheless, a more confident change in tone is granted through sign gags and contextual appropriation of environments. If the camels aligned in parking spots resemble a car lot, then Porky resembles the indecisive consumer—his two choices lie between the flashy, more elaborate “HUMPMOBILE” (Clampett teasing the censors with the “full of gas!” tagline) and a more modest “Kiddy Kar”.

No matter how brief and comparatively unelaborate the acting on Porky may be, that there is a beat at all dedicated to his mulling over of the decisions bestows a humanization on both himself and the camels. Whimsical absurdity of the entire situation is embraced, the stakes of choosing the right camel raised and palpable and attempting to possess an identity outside of a throwaway visual gag.

Porky’s choosing of the baby camel is rooted in founded cartoon logic—a squat, cute, infantile steed for a squat, cute, infantile pig. While plenty of comedy can be garnered from his attempts to bumble and wrestle with an incongruously large, hulking camel, that isn’t the comedic intent of Clampett’s mission in this case.

Adoption of the baby camel leads to more avenues for pop-culture references. “Eh-dee-eh-deeah-don’t worry Blondie, I’ll take good care of Baby duh-deh-Dumpling!”

While a nod to comic strips isn’t out of place at all for Clampett, it isn’t an entire act of self indulgence—Blondie would get another reference in Tex Avery’s Hollywood Steps Out. Likewise, Porky’s reassurances aren’t as surface level to squeak a gag in as they may seem—though a bit difficult to see through a comparative lack of exaggeration on her facial expressions, Blondie’s face falls briefly when Porky takes her brood before brightening up with the following reassurances. A good save to incorporate practicality with self indulgence and an easy way to get a laugh.

Carl Stalling continues to assert his musical identity and growing experimentation through an increasing insertion of original arrangements. In this case, the original number of his that would play most notably in cartoons such as A Wild Hare and Rabbit Seasoning accompanies Baby Dumpling scooping Porky onto his back through elastic distortions and arcs. First heard in Snowman’s Land, the piece approaches a more finalized sound than the slightly different arrangement heard in the former.

Mischievous and furtive, it provides fitting accompaniment for the equal playfulness in the animation—when Porky tumbles to a halt, he’s facing backwards. That is rectified through another jolt from the camel, a comedic beat lingering on Porky's backward stance to ensure the audience catches the mistake. A bit needlessly elaborate, sure, but rightfully jovial in its execution.

John Carey’s layouts for the cartoon are followed obediently in the adjacent scene seeing as he animated it himself. Through the courtesy of a “Geh-gee-geeih-giddyap!”, Baby Dumpling and Porky set off, their movements strictly accompanying Stalling’s laden orchestrations of “Streets of Cairo.”

Synonymous to Porky urging his camel to “suh-WING IT!” in Porky in Egypt, musical timing seeks to be a gag first and foremost through overzealous movements dutiful to the music. However, it feels comparatively more forced here in its desire to be humorous than the former example. Perhaps it’s due to the former example styling its animation off of a similar cycle from Little Beau Porky, whereas the walk here is from scratch. Mainly, feelings of comedic obligation come through Porky’s hat bobbing up and down off his head with an arbitrary amount of energy, as well as the twinkle-toes maneuvers from the camel matching a flute glissando in the music. It’s nevertheless energetic and polite, serviceable for the playful tone sought out by Clampett and Millar, but has potential to feel less forced.

On a much less overt note, Millar and Clampett get somewhat creative on their scene transitions. Rather than sparking a jump cut or a cross dissolve to the coming wide shot of Porky and his camel approaching the fort, a fade to black is utilized instead. Such a fade hints at a sense of finality, a coda, a passage of time that bears a heavier burden than the more airy cross dissolve. That the music stays the exact same and doesn’t even skip a beat makes the transition feel somewhat arbitrary, as though time has both elapsed and hardly moved at the same time. It’s a nitpick that is much more fascinating than it is detrimental—always intriguing to view a somewhat unconventional scene transition and how the tone can differ from something so menial.

Attempts to subvert the “cartoon characters as legionnaires fighting against Ali-Baba or a reasonable facsimile” genre continue through gags and actions that seek to trivialize the weight of the premise. In this case, the fort is branded with a comedic discrepancy through domesticity—a pile of milk bottles waiting to be taken inside indicates that the fort hasn’t been occupied for a number of weeks, something audiences then could relate to and laugh about. Porky’s glance at the bottles is a bit stilted and quick, consisting of him bending low for a second before focusing on a nearby note, but nevertheless seeks to acknowledge the gag and give it a vague purpose outside of a visual tease.

More notes means more time to pad and more opportunity for laughs. Through the courtesy of a close-up shot, we discover that the fort’s solitude is not out of defeat or desertion, but rather a direct result of the legionnaires out at a convention. Colloquialisms such as “me and the boys” or the decidedly effeminate signage of “hugs and kisses” from an army general establish humorous informalities not incomparable to the domesticity of the milk bottles; playful dismissal of threats and clichés serve as the cartoon's mission more than establishing a solid story. That comes as both a benefit and a detriment.

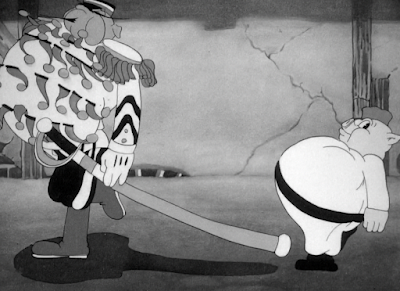

Of course, not all clichés are abandoned. Porky’s delivery of “Well! An' I was eh-wuh-weh-worried about those guys,” that is equal parts relieved and dismissive sparks an inevitable rebuttal. Following the panning technique flaunted in Chicken Jitters and Africa Squeaks, distance of the desert is exaggerated through a cross-dissolve of the pan halfway through, indicating a slight passage of time and rendering the landscape more barren and vast than it really is. It is then that the camera settles on Ali Baba himself, peering through a pair of binoculars in a set-up synonymous to Ali Mode’s introduction in Little Beau Porky.

Correction: beer bottles. Another subversion that seeks to minimize and poke fun at the threat Baba serves. Interestingly, getting back to technicalities, Clampett and the camera crew get creative with the motions of the camera itself. A maneuver that would be reused in forthcoming Clampett shorts, the camera seems to jiggle in place, touting its own overshoot just slightly to the left before settling on Ali Baba once and for all. As new methods of manipulating camera movements were sought, new life could be breathed in the shorts by allowing the camera to follow the same principals of motion and exaggeration as the animation on-screen. Indeed, an added pep and vigor results.

Whereas Ali Baba’s presence is derivative of Frank Tashlin in its delivery, his formal introduction follows the Tex Avery school of thought through on-screen captions. Claims of his being “the mad dog of the desert” are taken literally; Mel Blanc supplies Baba’s frantic, high pitched barking noises as he imitates the likes of a puppy with a superiority complex. Somewhat polite, feeling a bit like surface level cribbing rather than an established gag Clampett and Millar were truly devoted to, but serviceable for the overarching tone of the film.

Now, comparisons to Little Beau Porky grow much more concentrated. Both Ali’s whistling for their thieves maintain some form of original identity—Tashlin’s is straightforward, whereas Clampett and Millar have Baba’s fingers morph directly into the shape of a whistle, something more akin to Clampett seeing as such transformative humor can be found in a number of his shorts—though the animation of the thieves popping up from behind the sand dunes is directly reused from the aforementioned cartoon.

Recycling of Carey’s camel walk cycle as Porky and Baby Dumpling head back is interrupted through commotion off-screen. Like any cartoon in the golden age placing a focus on Ali-Baba and his forty thieves, defamatory stereotypes are ripe for the pickin’, and here is unfortunately no exception.

To give credit where credit is due, the camera trucking in on the legs of the thieves as they run seeks to make it seem as though they’re coming closer to the camera, thusly feeling more overwhelming and overpowering. Focus weakens as the camera trucks further in—not an intended side effect—but doesn’t detract from the intent of the visual. Likewise, it cheats having to do any actual perspective animation of the thieves getting closer. Lazy, but admittedly clever.

Thankfully, Porky’s reaction to his pursuers is less lazy. It’s a stutter gag, but one that seems to have genuine motivation and thought behind it rather than a throwaway bait-and-switch to fit a quota. Rather, aimless, petrified, unintelligible gurgling as he and his camel stand frozen in place soon give way for a starkly nonchalant and controlled “Goodness gracious.” While there’s a pause just slight enough between the wordless exclamations and the actual phrase to make the delivery feel stilted and unnatural, the contrast itself is palpable and a gag that feels more strongly rooted in actual personality rather than obligation.

Elastic theming on the camel’s body physics are upheld through his and Porky’s exit. Though slightly hindered through even timing and spacing of the animation itself, the camel looping its spindly neck through its own legs—prompting Porky to be carried through the resulting somersault—is plenty spirited as he bursts into a run. Playful and eccentric, but quick enough to feel nonchalant and natural rather than attention seeking.

Grips on the audience's attention are delegated for the coming gag. Somewhat of a takeoff from the cat lifting up its “skirt” to panic and shriek effeminately at a mouse in Pied Piper Porky, the camel interrupts its run only to lift up its own fleshy skirt and tinker delicately across a mud puddle. Mirroring the gag with rhythmic, rapid run cycles allows the juxtaposition to read boldly in both demeanor and speed. Clampett and Millar seemed fond enough of the gag to use it again in Prehistoric Porky.

Loyalty to previous gags are maintained through a shot of Porky and his camel seeking refuge in the fort; the stack of milk bottles outside topple in the wake of their rushing by, the note from the general floating to the ground. A small, somewhat menial gesture that nevertheless offers the slightest continuity to render the cartoon cohesive.

Sustaining an overarching tone of whimsy, the barricade that Porky slams shut once inside the fort is shaped like a burly fist for no other reason than it can be. Animation on Porky himself is somewhat weightless, aimless in his scrambles, but rightfully energetic—the cel layer containing the bolts that hold the barricade shut disappear for a few frames, prompting a flash on screen, but isn’t glaringly noticeable if the audience is meant to focus on Porky instead.

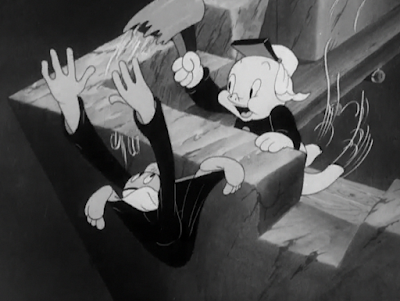

A knock on the door prompts the barricade to bulge. Thus reveals reveals a pair of thieves using a human battering ram to get inside; suspense of the intruders is heightened by cutting to the reveal after the first knock on the door rather than before, making their appearance seem all the more surprising and abrupt.

Trivialities continue, this time through a vase conveniently labeled “HEADACHE PILLS” as one assistant tosses them into the mouth of the human battering ram with each blow. A close-up shot on the collection of pills is redundant in its clarity, allowing the rhythmic momentum to falter. Nevertheless, the entire setup is nevertheless reminiscent of Clampett’s comically minded cartooning sensibilities, especially through such excessive labeling.

Whereas Little Beau Porky’s climax prioritizes cinematography and excitement, Ali-Baba Bound prioritizes puerility. This can be both a great strength and a weakness depending on the intent in tone or the gag being conveyed. For example, cutting to some of the thieves using a carnival strength tester to propel a man into the air and fire over the fortress wall feeds perfectly into the tone Clampett is concocting. Matter of fact, surprising, but rooted in a warped sense of logic that is appealing and believable through conviction to the gag.

Porky’s gun deflating after each burst of gunfire, however, is not. Such is a moment where the trivialization comes as a weakness and seems to lessen the urgency of the brawl; Porky’s alarm and retaliation seem somewhat dutiful, manufactured, an obligation to the story rather than a founded reaction. Because it is not as strong of a gag as the strength tester, it falters in the same exact manner as Porky’s gun itself.

An insatiable urge to push the boundaries can be just as detrimental as it can be helpful with Clampett. In this case, he deliberately seeks to shock the audience through the egregiousness of depicting a suicide bomber with a shell strapped to his head, sitting on a bench as though he were spectating a game of football, signage deliberately ensuring the audience does not miss his role. There is a certain respect to be had for the Clampettian urge of transforming such a brawl into a sports metaphor, but pushing and perpetuating further stereotypes does little to further one’s appreciation of the staging.

At the very least, Clampett and Millar don’t ask the audience to take the bomber seriously. In fact, they beg the complete opposite; a certifiable creature of Clampett’s creation, the bomber provides a vessel for his self-indulgent screwballisms. While this is already evident just in the premise and design itself—short, squat stature, single toothed grin, crossed eyes—a constant hunger for overtness carries over into his dialogue and mannerisms.

“Boy oh boy oh boy oh boy oh boy”s are plentiful in his circuitous, high pitched declarations expressing his wish “to get in an’ battle!” John Carey’s drawings are as appealing as they can be, solid and expressive in construction, but the motion itself seems unguided and gratuitous, as though stepping off the bench and back on again will succinctly convey his battle-hungry restlessness. Instead, it reads as awkward and stilted—that applies doubly for the camera panning to accompany the movement, sliding forward a few inches only to return back when the bomber sits down. A mechanical restlessness and one out of gratuity rather than pure spontaneity.

Much of the brawl’s takes inspiration from the battle in Scalp Trouble (which is blatantly expressed in the shot after this one, borrowing the layout from a shot in the aforementioned cartoon), serving as a nonstop barrage of gags rather than a true moment of strenuous climax. Here, one of the thieves winding up to run off-screen and instead tinkering daintily up the side of the wall feels synonymous in its pacing to the Indigenous man burning a hole in the side of a fort in the former, approaching with equal effeminacy. There isn’t enough contrast between the wind-up pose and polite run to land the joke at maximum efficiency here.

Regardless, that doesn’t prevent Porky from walloping his visitor over the head with a mallet in the Scalp Trouble-adjacent overhead shot. While some of the inbetween drawings of both characters are crude (particularly on the villain, whose eyes are mere dots in the distance, a drawing trademark of Clampett’s), the energy conveyed through motion, structure, and sound is solid.

Porky popping out from behind the wall rather than waiting from the start sustains the surprise element, the sound effects of both the villain climbing and the loud smack of the mallet bring newfound exaggeration to the impacts, and the warped perspective on the composition itself evoke motion and dynamism through diagonal angles and towering height. Stalling’s ongoing accompaniment of “The Girlfriend of the Whirling Dervish” growing in a crescendo once the action picks up is an equally important keystone to accentuating the impact.

Clampett would reuse a synonymous gag of the villain striking against the fort in Nutty News with an unrelated vignette—one that is slightly less cruel but nevertheless dry in its intent. Tricking the audience here by having the thief prepare to gear up for a run in the same pose as before is at least a clever bookend and much stronger discrepancy between poses than seen in his introduction.

Elsewhere, an anecdote of a man firing from the wall, wobbling back and forth on oversized feet like an inflatable doll is somewhat ill-fitting in its placement. The gag would have felt more at home had it succeeded the strength testing gag, melding into the rapid fire pacing and clinging to the playful, toy-like atmosphere. Here, it completely lessens the coda implied by the former striking gag, much more polite and disposable in its presence.

A more sympathetic note is nevertheless sought after as we cut to a trembling Baby Dumpling. While the tears are cloying (and feel they are meant to read as so), it’s a solid attempt at garnering pathos and sympathy from the viewer. Especially when the shadow of Ali-Baba himself looms over the camel, dagger right in view. Conveying the action in pure silhouette rather than indicating the physical manifestation behind it furthers an air of added mystery, suspense, and threat towards the unknown.

Likewise, sharp timing on the actual impact of the dagger narrowly missing the camel elevates the stakes further. Instead of dedicating a deliberate beat to the camel sliding out of the way before the dagger has time to come down, the opposite occurs in that the dagger cuts through the air before the camel has moved a muscle. Timing the motion on ones and having only two frames between key poses enables a sharp jolt and added weight to the attack. Same with the dagger actually wedging into the ground—Ali Baba doesn’t hesitate nor get interrupted halfway through. An air of finality prevails, which, in turn, is more startling through such conviction.

While it’s true nobody puts Baby [Dumpling] in a corner, B.D.’s innocent cowering provides some good; a horn just so conveniently hangs in a nearby hook.

Ensue another subversion, this time of Clampettian influence through its transformation. Baby Dumpling’s great inhale into the trumpet doesn’t spawn the blare of a horn, but rather, a scream—the newly anthropomorphic horn screams “HEEEEEEEEEEEEELP!” in unmistakable Blancanese. It’s always hard to argue against a good ol’ Mel Blanc yell.

His cry for help is thankfully not in vain; through the aid of sentient typography—another Clampettian trademark that douses the cartoon further in the mindset of a comic strip or a graphic equivalent—Baby Dumpling’s pleas catch the ear of his mother, asserting that her own appearance isn’t just a vehicle for wordplay.

Likewise with her panic-stricken cry of “BABY DUMPLING!” to the camera. Blanc supplies her voice in his typical womanly falsetto, working well to support the cloying call to arms purposefully constructed through the intimacy of the close-up, everything halting to focus on her plea at the audience, and the name “Baby Dumpling” alone being uttered in a scenario of utmost urgency.

Embracing such a notion, warbled cries of “Baby Dumpling!” are plentiful as she hops out of the camel lot and towards her loved one, her run cycle not incomparable to one Pepé le Pew years down the line.

At least when in motion. In the midst of her run, she freezes to a halt—the same comedic philosophies seen in Porky’s Last Stand where Porky runs backwards to escape from the bull apply to Blondie’s backwards galloping towards a conveniently placed gas station. Abrupt, bold, a caricature of movement and ideas (as well as a good way to save a few bucks by recycling the movement instead of animating her turning around), the maneuver feels less like a cheat through a wide shot dedicated to showing her backwards galloping. It would have been easier to have her skid into the gas station at the same camera registry, but less clear or playful at the same time.

A gas attendant lifting a hatch on one of Blondie’s humps (his Marvin the Martian-esque “Fill ‘er up, lady?” unaccompanied by a lip-sync, perhaps added in at the last minute) seeks inspiration from the same gag in 1937’s Popeye the Sailor Meets Ali Baba’s Forty Thieves, hump-engine metaphors and all.

As to be expected, the example in the Popeye cartoon is much more prompt and streamlined, with Clampett and Millar placing a heavier focus on the mechanics of the camel. The attendant cranks the camel’s tail like an engine starter, a brief glimpse is granted of engines pumping inside humps, a beat is dedicated to displaying Blondie gearing up to speed. Popeye succeeds through its confident delivery, but the amount of time poured into the gag in this cartoon indicate a dedication from the filmmakers; one can definitely sense that Clampett found it funny.

“The Girlfriend of the Whirling Dervish” reaching a musical climax in the background scores the added urgency with Blondie’s newfound energy. Such is furthered through comparatively more dynamic staging—as she finally gets up to speed, a brief perspective shot is delegated to the camel narrowly brushing the foreground as she runs in and out of view from the camera, immersing and integrating the audience into the action.

Likewise, while the impact itself is polite in comparison to the sheer amount of energy present in the build-up, the audience receives a clever fake-out in that Blondie barrels through the fortress wall rather than the door to get in. Ambiguous staging and spotlight on both the wall and door don’t seek to give away any hints to the audience, nor is there any preparation or indication in the action instead. Blondie bursting through the wall is somewhat even in its timing, lessening its weight and overall impression on the audience, but the speed is nevertheless sustained and successful in allowing the subversion to hit.

Repeated cutting between the ever approaching Blondie and Ali-Baba backing Porky and Baby Dumpling in a corner attempts to sell cinematic urgency; that much is true, but that it only cuts from Blondie to Porky to Blondie again before the resolution somewhat trivializes the action and renders it comparatively anti-climactic. Even just one more cycle of Porky and Blondie again would have worked—nevertheless, the intended alarm is still there, just not to its fullest extent.

Said resolution arrives in the form of a good old fashioned headbutt. A quick beat is dedicated to a sliver of pathos, Blondie grinning proudly at Porky and Baby Dumpling, but the reaction is somewhat stilted through the reactions of the latter two—Porky especially looks as though he got caught mid-blink rather than touting an expression of gratitude.

John Carey yet again proves to be a ripe fit for the animation of Ali-Baba catapulting from the fort, flopping onto his stomach, and grimacing, his men surrounding him in support. While difficult in these reviews not to make it seem like Carey is the only animator whose work deserves any sort of kudos—far from it—his sense of tactility in motion and anchored exaggeration in drawing style are a wonderfully refreshing burst of appeal. Animation in Clampett’s shorts from this time has a tendency to appear melty or unpolished, vague, so the confidence and tightness in Carey’s designs and motion are not taken for granted. Him being Clampett’s layout man certainly aids in his clarity as well.

Clampett’s self indulgences return as focus is shifted back to the suicide bomber, still “boy oh boy oh boy”-ing about his “big chance”. Screwball sensibilities on the bomber feel much more transparent and decorational rather than rooted in any sort of conviction.

Compare Clampett’s screwball approach with Daffy to the approach with the bomber—while there’s an obvious disconnect, seeing as Daffy is an established personality and character, there is admittedly much more control and an arguable sincerity in his ventures with Daffy than what is seen here.

Perhaps that comes from knowing we are never going to see this guy again after the short ends and there’s a desire to make the runtime count, throwing as many zany antics into his appearances as possible, but he nevertheless seems to betray Clampett’s “breakout” theory in that the hysteria hits hardest when there’s a buildup to juxtapose that. No such incongruity nor preparation is granted here.

Nevertheless, the bomber (now imitating a car horn as he charges bomb-first towards the fort), in spite of his transparency, brings closure to the cartoon. Even if said closure arrives in bombing his own men through quick thinking from Porky and the camels, each opening doors the fort to let him through and run past them. Straight ahead perspective shots birth added dynamism, again immersing the audience in the action as they share the point of view of the bomber. Repeated cutting back to the bomber, his continued commentary of “Outta my way! Outta my way!” and a foreboding drumroll score likewise seek to build a facetious tension.

We end on a punchline that is prompt and (no pun intended) vacant as the impact of the bomb prompts the robes of the thieves to transform into makeshift tents, an “ALI BABA’S AUTO CAMP” sign fitting accompaniment for the camel car lot.

Ali-Baba Bound is a cartoon best viewed through its details. On a larger scale it’s mediocre at best, egregious and insensitive at worst, another 7 minute obligation that is an easily dispensable cartoon in Clampett’s filmography and the red-headed stepchild to the cinematographic excellence of Little Beau Porky.

Conversely, viewing it through individual vignettes and details does paint a somewhat more appreciative picture—Porky has more than two lines of dialogue and his share of briefly inspired moments (such as the “goodness gracious” gag or acting decisions like the sneaky side-eye), Clampett’s passion for comic strip cartooning can be seen through glimpses of typography or something as unsubtle as repeated references to Blondie, John Carey’s animation is as appealing as ever, and the desire to subvert a genre through gags that trivialize threats and make them playful first and foremost is admirable.

Regardless, it is far from Clampett’s best—having a very similar cartoon potentially written by the same writer with a result that is much more gripping, coherent, and engaging does not allow this short to read favorably. Little Beau Porky is not without its own issues (harmful stereotypes being the biggest), but it is a great example of “less is more.” Frank Tashlin did not seek to rise a reaction out of the audience through insane suicide bombers who make funny noises. Likewise, Beau’s Ali-Mode posed more of a threat and had the slightest semblance of personality (carried through Billy Bletcher’s joyously booming vocals) rather than serving as a total obligation and set piece. The same can be said with Porky; while he has more lines in this one, he feels much less stock in Beau, despite being a cartoon produced in an era where the directors were still trying to secure his identity (and the cartoon being directed by a person who has openly confessed his hatred for the character.)

If my hypothesis is correct in that Millar wrote Little Beau Porky (and I myself confess that I have no evidence for this outside of Millar’s frequent association with Tashlin and similarities in synopsis, so this is pure speculation and not meant to be regarded as fact), then Ali-Baba Bound is a cartoon whose identity and subsequent issues can be attributed much more to Clampett.

Even if Millar didn’t write Beau, Clampett’s influence is still very potent from constant pop culture references to self indulgent screwballisms to transformative gags and subversions. Clampett’s love of mischief and whimsy is as helpful as it is detrimental—had the short followed a more serious approach, I feel it would have suffered even more than it already does.At the same time, constant trivializations eradicate any urgency upheld by the antagonists, making it hard to sympathize with Porky or feel any sort of investment in the story. In all, this cartoon is a great indication of how Clampett’s self indulgent tendencies can be just as destructive as they can be empowering.

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment