Disclaimer: This review contains racist content and imagery for historical and informational context. I encourage you to speak out should I accidentally say something that is harmful, perpetuating or ignorant--it is never my intent and I seek to take accountability, should that occur. Thank you.

Release Date: January 27th, 1940

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Chuck Jones

Story: Dave Monahan

Animation: Ken Harris

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Shepperd Strudwick (Narrator)

(You may view the cartoon here.)

Just as there is a fascination with viewing these cartoons in their fledgling stages, witnessing an iconic array of characters, gags, approaches, deliveries, techniques in an amoebic stage waiting to hatch, knowing what they will become, there is an equal fascination in projects that barely materialize into anything more than an idea.

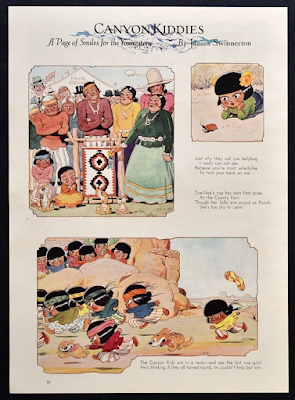

There was a lot of hubbub around the studio in the latter half of 1939. In a volume of the studio’s newsletter dated August 25th, talk was rife of production on a new cartoon series based off of James Swinnerton’s Canyon Kiddies, which he drew for Good Housekeeping starting in 1922; it ran all the way to 1941. He was brought on to paint the backgrounds for the cartoon—in oils, mind you, an extravagance in itself compared to the studio standard of watercolor—and the Jones unit even took a trip to a reservation in Arizona to film reference footage. Not only that, a full page advertisement for the cartoon in color featuring stills from the cartoon appeared in The New York Journal American. Surely from the sheer amount of preparation alone, the series was slated to be something unique and grandiose, not to mention long lasting.

This was the only Canyon Kiddies cartoon ever made.Viewing the cartoon, it isn’t exactly difficult to see why. Even for 1940 Jones standards, the short is painfully bloated—it’s unclear whether the 8 and a half minute runtime is a byproduct or a cause. Overcompensation in striving to emulate Disney when even Disney themselves were beyond such cutesy antics or molasses timing in their short subjects didn’t deliver favorable results, as audiences were growing more accustomed to the ever quickening pacing and humor in Warner Bros cartoons. Likewise, Jones has plenty of other Disney look-alikes that aren’t half as meandering.

Nevertheless, we are met with the antics of the Canyon Kiddies on which the short is derivative of; the cartoon follows the day in the life of the children as they hunt animals, attempt to ride donkeys, escape from bears, and so forth.

Actor Shepherd Strudwick provides the cartoon’s only source of dialogue as the narrator. The entire opening minute of the cartoon consists of idyllic camera pans, with over half a minute settling on a singular establishing shot alone (the composition appealing to Jones’ graphic artistic senses by splitting the screen in two between the canyons and the sky), granting ample spotlight to Strudwick’s orations.

Narratorial establishment and context seeks to create a setup that will be refuted and addressed later on, which is understandable. What is unfortunate is that the writing is so egregious in perpetuating and reinforcing negative, harmful stereotypes about Indigenous peoples. Derogatory language such as “fierce”, “wild”, “savages” and so on purposefully paint an image that is negative and offensive, much less wholly insensitive—claims of animals running in fear from the tribes is just insulting and ignorant when understanding how cherished and integral one’s bond with nature is to certain tribes.

While it is by no means excusable, there is an end goal to such lambasting claims—a rebuttal. That is, that we are told to be wary of such ferocious warriors meants we are meant to be surprised and endeared when we are instead met with a bunch of cute little infants. Admittedly, no matter how gross, the contrast and exposition are effective—Strudwick’s narration, suspenseful pans obscured through dark lighting, and purposefully misleading shadows projecting the images of grown adults all tease the audience and orchestrate an antithesis that is rightfully strong, yet coy.

Our introduction to the kids is that of a drum circle. Jones’ artistic sensibilities are strongest in gags involving some cloyingly out of place dogs—particularly one dog wagging his tail between two drums that feed into the rhythm. Animation of the children dancing around the fire is solid, rhythmic, smooth, the shadow effects are commendable in their intricacy and solidity, and gags involving a baby beating against a dog’s belly or a kid whacking a drum with a club seek to ease monotony. However, with the sequence taking up about a minute of the cartoon itself, monotony is difficult to escape.

Speeding of the rhythm, animation, and ferocity of the music as a whole are all respected and appreciated methods at trying to keep things fresh, but the number is just too attached to the saccharinity inherent to its premise. You can only laugh at a dog wagging its tail or a kid falling through a drum and staring dubiously at the audience so many times before it gets old.

Nevertheless, the finale of the drum circle officially brings the cartoon to a start only two and a half minutes in. We are met with perspective animation of the kids running past the foreground to begin their daily activities, an intermission provided only for an offscreen parent to grab one of the kids and begrudgingly make him carry his little brother. Construction of the kids are solid, the decision to run diagonally past the camera immersive and dynamic, intermission comfortable in its differentiation between pacing.

Still, that does not entirely dull the repetition. More running shots ensue to flaunt more perspective animation and the oil background paintings—the paintings are rightfully gorgeous and deserve a spotlight, but the overall pacing is meandering and circuitous.

Likewise, the kid stuck in the drum from before tripping and struggling to crawl out of it isn’t the comedic break Jones and company think it is. A juxtaposition against the rhythm of the story, yes, but not one particularly amusing. Instead, bloated stares at the camera and tripping upon an attempt to free himself follow the philosophies of Jones’ earliest cartoons: cute characters taking spills and falls is meant to convey an endearing vulnerability. Here, with the characters having barely any chance to endear themselves to us outside of “look, they’re small and cute”, it feels disingenuous

Transitions between scenes are a little rocky—no pun intended—as well. Mainly, the drum kid hops on his butt to slide down a ledge of rock, only for the camera to cut directly to him running across a smooth, horizontal surface, almost taking a spill over the edge. While meant to provide a transition to the antics of the other kids, camera panning down into the canyon and spotting the rest of the kids heading on their way, a lack of hook-up poses and continuity make the filmmaking feel abrupt and discombobulated.

His mournful expression at being left behind seeks to rise more sympathy from the viewer, but mainly feels bloated and gratuitous. At least until he spots something off-screen.

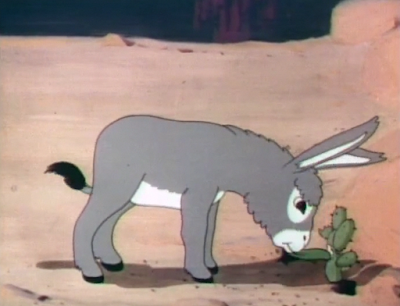

A reveal of a donkey gnawing on a cactus (an interesting and humorous commentary on the apathy of the animal, swallowing spikes and all yet seemingly unaffected) is one of the most intriguing aspects of the cartoon. Not for the content itself, but the music cue. Seemingly an original piece by Stalling itself, the song would prove to be the most long lasting legacy left by this short, appearing again in cartoons such as Hippety Hopper and Kiss Me Cat—both released 9 and 13 years after this short respectively.

Antics ensue of the kid hopping on the donkey’s back, hoping to ride it down the canyon and join up with his friends. Knowing Jones and his adoration of slow-burning, apathetic characters and general general frustration comedy, that is never meant to be.

Indeed, what ensues instead is a somewhat laborious sequence dedicated to the kid struggling to move his steed. Stalling’s jovial—if not at times sardonic—musical commentary sustains the most interest, though the kid falling over himself (manufactured as the delivery may be) is smooth, elastic, a fleeting but welcome burst of energy.

Same for the ol’ running take after he feigns disinterest. Treg Brown’s sound effects of whooshing air are an unconventional but appealing take on the motion, different from the typical shoe scuffing sound effects that ensue under synonymous takes. Bloated timing of the sequence does seem just as accidental as it is purposeful—purposeful to provide necessary antitheses of energy such as this one, accidental in that the same languid pacing infects the entire cartoon.

Like everything else, the running take proves to be a failure. Similar to the kid falling over himself, his collapsing beneath the donkey feels manufactured and too orchestrated in its execution, as though he purposefully dove under to get crushed. Regardless, it serves as a segue to pure Jones territory—there would be many a take in a Chuck Jones cartoon that mirrors the disgruntled expression of the kid beneath the donkey’s ass. Insulting flicks and twirls of the tail again speak to Jones’ comedic sensibilities as a topper.

Elsewhere, living up to the cartoon’s title, we follow two children armed with bows and armed with the intent to hunt. Swinnerton’s oil backgrounds are a visual delight, particularly through a pan of the kids walking along and interacting with objects in the foreground and background—passing behind trees, walking along curves of the trail, etc. to further the believability of life and depth.

Just as the same was achieved by the kid tripping and falling out of the drum, Jones attempts to evoke empathy and endearment from the characters through bumbling, naturalistic gestures. In this case, the two kids bumping into each other.

Their collision prompts a realization—a chipmunk attempts to crack open a nut in a nearby tree. Through careful, sculpted animation, one of the hunters aims directly at the chipmunk’s face. Inquisitive head tilts on the chipmunk are of particular appeal.

Had this cartoon been produced a year prior, the chipmunk likely would have engaged in a wild take before fleeing. However, this is a Jones who is more experienced and had a little time to seek artistic identity. As such, synonymous to the eponymous dog gulping down some popcorn in guilty conscience in The Curious Puppy, the ‘munk here merely swallows his nerves.

Thus incites a lengthy pantomime sequence—though that could be used to summarize the cartoon as a whole. Acting on the chipmunk is the strongest center of focus and appeal, particularly the toothy, guilty grin upon hiding from his pursuers and only to be met with them from the other side of the tree. Sliding, sardonic string scores from Stalling rightfully score the action and inform the tone, most palpable at the guilty grin.

Sound effects likewise do a great job of informing action obscured off-screen. Particularly when the chipmunk settles on the arrow itself, covering its eyes—the kid releases the arrow, only to be met with a metallic quivering sound in the background. Sure enough, the camera pans left to reveal the chipmunk lodged into a branch of the tree, arrow still rife with movement as it shakes to a stop.

Of course, the chipmunk is not a priority in this cartoon (though perhaps the short would be a bit more engaging if it were.) Instead, we cross dissolve back to the donkey from before, removing itself from the head of his wannabe passenger and continuing to gnaw apathetically on some cacti.

Jones returns to the fake out-and-run method, which was cute once but cloying when used in rapid succession. In every scene involving the kid and the donkey, that exact approach is reused. It becomes less of a subversion the more frequent it’s use—this blatant repetition is synonymous with the issues in Dog Gone Modern, primarily involving the same laborious dishwashing sequence and the Boxer puppy through multiple segments of the cartoon.

While not to nearly the same extent here—and mercifully so—it demonstrates that the priority is not exactly on clever twists on the same gag nor really the gags themselves. Rather, cuteness is the priority. How else are you meant to interpret the briefly victorious glance of the kid as he climbs onto the donkey’s back before being thrown off again? He is successful in this cuteness, but the saccharinity is difficult to digest if you aren’t the audience Jones and company had in mind while making this. Just because something is cute and appealing does not give it an automatic pass to be engaging nor compelling. It comes off as a crutch.

Nevertheless, more attempts at endearing antics ensue between boy and donkey as he throws himself around the neck of his steed. Thus prompts a close-up of the donkey licking the kid’s face as our means of transition; Stalling’s string orchestration feels warmer than the acting on the screen itself. Still, the motion in which the kid propels himself into the donkey’s neck is fluid and solid, almost intoxicating in its prioritization of weight.

With all of this said and done, Jones and company do deserve praise. Particularly on coherency and consistency with multiple storylines; granted, these storylines barely have much substance to begin with, but there are kudos to be had by showing multiple characters heading on multiple, separate ventures in a way that still feels coherent to the overall tone of the story and connected. Outside of spot-gag cartoons (which aren’t often based in story to begin with) there haven’t been many—if any at all—shorts to have more than two diverging storylines. Conflicting storylines can be difficult to execute in a manner that is coherent, but this is a comfortable exception.

Now, we follow the antics of the kid from before saddled with his baby brother. More importantly, we follow a bear following the antics of the kid and his baby brother. Jones makes a point to emphasize that these backgrounds and environments are lived in and more than mere decoration. While much of this materializes in perspective animation, having characters round corners or go behind trees or walk in curving directions, here, use of the bear’s cave is employed as sniffing sounds reverberate in a hollow, tinny echo before revealing the bear itself.

Intricate perspective shots are a great priority in this short, such as the downward shot of the infant holding a peppermint stick. Exaggeration and dynamism of the angle is impressive in itself—that it tracks characters and objects locked in constant motion are even more impressive.

More Jonesisms ensue through fourth wall breaks as the bear grins at the audience—his intentions are clear, further clarified through a mouth full of saliva.

A return to a previous layout provided yet another bridge between actions as the bear hops down from his stoop and pursues the boys. Recycling the same background and enabling all characters to move in the same direction promotes symmetry, parallels, a consistent and easy to grasp bookend that tightens the story together and alludes to forthcoming antics.

Dissolve back to the kid and his donkey, animation and gags alike reused in his pursuit to board his steed. While the shtick has grown old by now, the repetition seeks to represent a gag in itself just through pure association of its appearance. This time, the kid’s winding running take prompts him to rush past the donkey and tumble into a pile of rocks off-screen. More politely amusing Jonesisms apply, whether it be the donkey’s fur rustling in the wake of the breeze manufactured by the rush or the innocent discombobulating of the kid slumped over himself in the rocks.

More gorgeous oil paintings are flaunted as a return is made to the bear and the brothers. Instead of being startled by the lumbering giant, the baby only observes as the bear steals a lick from the peppermint stick…

…and receives a konk on the snout in return. Tears from the bear are unnecessary, especially considering he continues to follow them as we wipe to the next scene, but slapstick is slapstick. A diagonal wipe to the next sequence is somewhat unconventional compared to a typical cross dissolve, but endearing, kitschy in a way.

Such a wipe takes us back to the two hunters. Specifically, the two hunters who stumble upon the two brothers. Here is where props are due for converging the multiple storylines together—as previously mentioned, it is something difficult to do coherently and interestingly. The meeting here feels natural and believable rather than gratuitous, especially considering the hunters have a clear objective in mind: to hunt.

Symmetry on the two boys aiming their arrows is a stylized, bold, appealing maneuver and a refreshing contrast to the tone of a cartoon who preaches believability and lifelike illusion first and foremost. To see any degree of caricature is a win.

Even if that doesn’t last long.

Finally, after some very glacial yet solid, well constructed animation of a minor search, the older brother grows wise to the presence of the bear thanks to the wordless warnings of his friend. No matter how slow and lumbering the pacing may move, it is almost granted here, as the construction of the animation is visually attractive enough to warrant such lingering.

Layouts and composition continue to be one of the most intriguing aspects of the cartoon. Jones and team get creative by granting a direct up-shot of the bear peering down at the kid; while a touch of awkwardness does settle due to the complete lack of motion, making the bear seem petrified and stiff, it succinctly conveys both a height and power disparity, making the kid feel just as physically small as he is metaphorically.

Growing attached to the vulnerability and humanization inherent to the action, Jones initiates another gulp take on the boy.

Transitions between scenes are still a touch rocky, needing just a bit more clarification, but not to an egregious extent. Focusing on a shot of the brother trepidatiously backing away, the camera immediately cuts to all of the boys backing away from the bear—a slight jump is noticeable in the pacing, which could be smoothed by showing the hunters standing still for just a second before also moving backwards, but the intent is nevertheless clear.

Moreover, the kids backing away serves more as a bridge between actions rather than a concrete act of focus in itself. It provides an opportunity for one of the hunters to tiptoe against the ledge of the rock, cautiously toeing the edge in an act that isn’t incomparable to the many airborne takes and walk cycles from Wile E. Coyote.

Peering down over the ledge provides another dramatic down shot of the cavernous canyon. While the perspective isn’t nearly as exaggerated as so many synonymous layouts would be in future Jones endeavors—particularly his Road Runner efforts—it is still a solid breach in decidedly horizontal momentum and staggering enough to allow the kid to slip over the edge.

One fall soon transforms into three, the kids forming a human link and barely hanging on over the edge. The brother pulling down of the hunters’ pants in an attempt to hang on calls back to some of the earliest cartoons produced by Warner Bros, where gags involving exposed butts, outhouses, and other polite juvenility were all commonplace.

In this case, it seeks to be innocent and playfully naïve—it certainly isn’t a stretch to say that the boy accidentally pulling off his friend’s pants, staring at said pants while standing in mid-air, and scrambling to hook himself back on after the beat is one of the cartoon’s most inspired segments. Perhaps it stems from pure association, knowing how Jones would manipulate and exaggerate synonymous gags involving characters suspended in mid-air to a much more humorous and inspired extent, but the timing (no matter how sluggish) is nevertheless witty and believable.

Cutting back to the bear, now peering over the ledge himself, the peppermint stick still in the firm grasp of the infant catches his eye yet again. Little graphic lines being emanated provide added incentive, worth, and novelty, a staunch indicator of the bear’s fascination and painting the comestible as a prize. All seem more appealing than the reality of it being a half-eaten stick of candy.

The inevitable ensues as the bear topples over the edge, a victim of his own overzealous grabbing. While timing is still sludge-like, brush trials on the bear’s paw as he grasps introduce a slight sense of urgency and energy that are welcome in their conviction.

Besides, his fall isn’t entirely for naught. In a clever maneuver from Jones, the camera provides a very brief glimpse at a now empty-handed infant during its pan downward to the bear. Candy cane happily in his grasp, the bear enjoys his treat on the sanctity of a tree branch conveniently jutting out from the canyon’s ledge. Again, to the credit of Jones and his crew, the branch doesn’t come as an entire surprise nor transparent safety net—it was visible in the down shot of the kid peering over the edge. What appears to be a mere decoration in fact transforms into a proponent for the resolution.

Anticlimactic as the kids pulling themselves up may be, a maneuver that is a little too seamless and perhaps even fruitless juxtaposed against the past minute of the cartoon, it’s nevertheless prompt—the same cannot be said for much of the same cartoon.

Instead, a distant shot of the kids running in silhouette, illuminated by the approaching dusk lighting indicates the cartoon is coming to a close. Such is furthered by the grandiose transition to the twilight, bold yet sincere musical accompaniment scoring the resuming of Strudwick’s narration.

Disparaging comments about the animals being free to “timidly venture forth” and other harmful stereotypes about skin color also resume with the narration. Nevertheless, Strudwick’s intonation and tone strikes the calm, storytelling timbre Jones was seeking. It evokes the rightful sentimentality evoked by the kids turning in for the night, placing a solid footnote and concrete end to our story…

…or so we think.

The most intriguing aspect of Mighty Hunters is undoubtedly its legacy. Or, conversely, its lack thereof. Viewing what were once slated to be grandiose, inspired plans barely see the light of day or get off the ground is almost more fascinating than viewing the birth of ideas or characters that do stick. Amazing to think that so much publicity and preparation was poured into a one-and-done deal.

It isn’t entirely difficult to understand why the series didn’t last, as again mentioned before, even Disney wasn’t this languid and cloying in its cartoons at this point in time. Cute is not a substitute for substance. Disparaging racial stereotypes and comments from the narrator do little to inspire a desire for more, either, but that doesn’t seem to be a reason for the discontinuation of the series.

It is Jones at his most regressive. Layouts are gorgeous, Swinnerton’s oil backgrounds are lovely—hard to imagine the same effect had this been painted with the usual team of Art Loomer’s vague painting style—and the animation is solid, meticulous, appealing, but all of that sadly aren’t enough to sustain a cartoon when there’s barely anything to be sustained. Good drawings cannot save bad timing or threadbare storylines.

At the same time, knowing the context of Canyon Kiddies itself, it’s understandable. The format of the series is nothing but anecdotes, illustrations with adjoining captions in rhyme. As such, Mighty Hunters seeks to replicate such an anecdotal format by orchestrating the cartoon in blurbs. The boy and his donkey is meant to be one anecdote, the brothers and the bear another anecdote, the two hunters one more.

Imagining these storylines as individual panels on a page is more in tune with the intended tone—while it is certainly respectable in the attempts to keep the animated adaptation true to the format of the series, there isn’t enough substance to pad out the entire cartoon’s runtime. Perhaps that’s why Jones, Schlesinger and company never made another—outside of audience reception, it’s possible they realized the flaws inherent to this particular adaptation and decided it was fruitless to maintain that.

Mighty Hunters isn’t completely dispensable, as it is a rightfully pretty cartoon and a fascinating novelty. While it may be somewhat far fetched of a claim (and I intend it as nothing more but a talking point), I do wonder what the fate of the Road Runner series would have been had Jones and company not taken the trip out to Arizona to study the surroundings.

I don’t at all believe this short was the inspiration for the series—that could be chalked up more convincingly to Frank Tashlin’s The Fox and the Grapes over at Columbia Screen Gems in 1941–but I do believe the studying and preparation that went into constructing authentic environments here was helpful to constructing the desert establishment of the Road Runner cartoons, even if only on a subconscious level. Some of the layouts offered in this cartoon, particularly the one of the boy peering over the ledge of the rock and into the abyss of the canyon, are certainly comparable to the layouts in the Road Runner series—just with the added benefit of more experience, more exaggeration, and having an absolute powerhouse of a draftsman like Maurice Noble on the team.

A failed experiment, but not necessarily one that isn’t interesting. Viewing the cartoon with an acknowledgement of its history and the ambition behind it allows for a more sympathetic viewpoint, but that is speaking purely from a historian perspective—audiences in 1940 didn’t have that same benefit.

.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment