Release Date: December 30th, 1939

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Chuck Jones

Story: Rich Hogan

Animation: Phil Monroe

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Puppies)

(You may view the cartoon for yourself here or on HBO Max!)

Fitting is it that Jones ends the year the way he started: with a Curious Puppies short. Perhaps even more fitting, however, is ending the decade on a cartoon whose influences are the exact same as the very first shorts of the same decade, where the Disney attitudes dominate both.

Warners have gotten much better at placing their own spin on the Disney philosophy, and in the best cases dismiss it entirely. Still, while Jones seeks the Disneyesque ideology of cutesy antics and the illusion of life with rich, attractive visuals, his own directorial flair can still be seen in a number of aspects that strengthen the short. Much of these advantages manifest themselves in the composition and layouts of the cartoon, often dipping into streamlined, geometrically minded stylization that, while still buried in the coat of "moldy prune” paint so lambasted by Jones himself, pokes through enough to bring attention to itself.

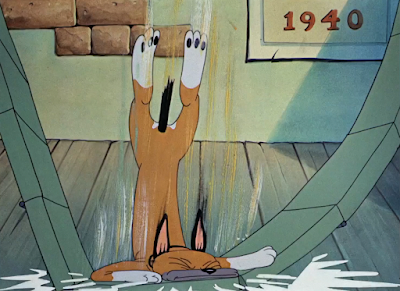

We end out the decade on a slightly regressive note, but, again, one that is fitting. A pure pantomime short, the littlest puppy of the duo finds himself strolling around an amusement park closed for the season. After a fall prompts the master switch to turn on and thus spark the park’s attractions to life, the noise awakens the Boxer watchdog, who seeks to perform his duties and get rid of the pesky little pup once and for all.

The Curious Puppy is most worthwhile through its composition and layouts, which is touted as early as the establishing shot. Tall, arching gates guard a sleepy amusement park closed for the season, promoting appealing symmetry as the doors split right down the screen. Warm, rich hues of gold juxtapose against equally warm tones of blue and green—a favorite color scheme of Art Loomer’s, who would soon be replaced by Paul Julian as the background painter for the Jones unit.

Such artistic endeavors are breached by the eponymous puppy, galloping past the gates only to return and squeeze beneath them. Since his debut with the puppies in Dog Gone Modern, Jones has gotten a stronger handle on finessing the realistic, Disneyesque movements of the pups, which alleviates some of the coyness inherent to their existence.

Timing the pup’s movements to the muted accompaniment of “Oh! You Crazy Moon” draws further harmony beneath moving characters and still backgrounds—Modern felt a bit disorganized in its execution, believability (or lack thereof) posing a big issue in the acting and direction. Attempts to rectify that with Prest-O Change-O become further realized here.

Still, Jones’ timing suffers from glacial pacing, particularly when the puppy struggles to shove its way through the gates and lands on its face. Too long an effort without the corresponding impact nor weight the timing demands.

Likewise with a rather anticlimactic take of the dog growing surprised and barking at something offscreen; signature early Jones head wobbles dominate as a byproduct more than the take itself, which is carried primarily through a quiet sting in the music.

A wooden cat silhouetted against the moon proves to be the object of the pup’s aggression. Despite some perspective issues on the sign and its typography, the composition is striking in its warped, diagonal angles and utilization of positive and negative space. Both the upward perspective and slanted angles justify the dog’s barks, as the cat appears taller and thusly more imposing as a result.

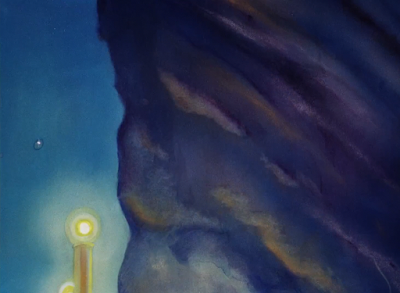

Visuals continue to grow inspired through stylization and silhouettes. Not incomparable to the silhouetted nighttime climax in Little Brother Brat, varying hues in the silhouettes—the pup is colored a deep navy blue rather than the inky blackness of the backgrounds—prompt the objects to stand prominently against the warm hues of the night sky.

Purposefully flat, horizontal staging evoke drawings first and foremost over flesh and blood characters, which inevitably attracts the audience further through such rigid, unnatural yet appealing geometry. Slow as the scene may pan out, part of it aims to encourage the audience to digest the stylization. A lone lamp illuminating a sign indicating the dangers of electrical gadgets succeeds in its simplicity and clarity. By calling such attention to a seemingly menial detail, its importance and relevance is thusly cued.

Indeed, the signage is no decoration; the pup falls from his perch, landing on the master switch of the park and prompting all of the rides, lights, noises, and everything in between to explode in a colorful cacophony. While the fall is belabored in its delivery, with focus delegated on the master switch much too long before the pup actually hits it, the pregnant pacing almost allows the introduction of the lights, music, etc. to feel more jolting as a result. A larger surprise after becoming accustomed to the sleepy atmosphere prior.

Lighting effects are another major strength for the cartoon, whether it be the airbrushing in the background paintings to simulate the glow or the variations of blues, pinks, and yellows promoting a greater antithesis to the primary color scheme of just blue and yellow.

Slipping various posters into the background has been a habit of Jones’ since The Night Watchman, and here is no exception. In fact, much of the cartoon feels like a vessel for minute background details, bestowing a specificity with the environment that other shorts may not have been able to provide—the settings feel more lived in and occupied as a result. Again with the believability.

Following a shot that lasts a few seconds too long with the curious pup’s eyes peeking out of the top of a trashcan, he’s quick to grow enamored with the electrical spectacle, engaging in more needlessly cloying, cute, Disneyesque endeavors before tinkering along. As mentioned before, Jones and company’s stronger grasp on the techniques and visuals they’re seeking to imitate make for a better viewing experience than seeking to imitate without the same skill nor knowledge. Pacing suffers greatly, and while some of the animation could benefit from more uneven spacing or greater weight, the motion feels much more cohesive than something like Dog Gone Modern.

An elongated horizontal pan asserts the short’s embrace of its environments. While the brushstrokes and the looseness Loomer’s painting style as a whole render it a bit melty, the attention to detail—no matter how quickly those details pass the eye—is appreciated. An employee entrance, closed for the season boards, curtains hiding exhibits, a shoutout to Coney Island and various flyers on the walls as a whole contribute to the warmth of the atmosphere.

Most importantly, however, lies the doghouse housing a watchdog in the corner of the fairgrounds. Enter curious puppy number two, the Boxer; parallels between the plucky energy of the little pooch and the lumbering movements of the Boxer have been a common theme in the curious puppy shorts thus far, and here is no exception. Contrasts in their disposition are strong as the Boxer practically has to drag himself out of his abode, yawning and blinking and meandering about. He notes the shift in atmosphere, but doesn’t appear to be in any hurry to stop it.

Dissolving back to the titular pooch grants us more symmetrical staging akin to the opening. Rather than a set of gates splitting the composition down the middle, both the pup and the middle of the giant swing ride serve as the divider instead, swing providing an equally helpful frame around the pup. Carl Stalling’s arrangement of “The Blue Danube” arms itself with a newfound quality of airiness to accommodate the motion of the swing moving back and forth.

Thus, a close-up shot is made, this time of the pup’s eyes tracking the swing. It’s unsurprisingly anticlimactic and straightforward—prioritizing solid animation and behaviors more than comedic potential—which comes at a slight hindrance given the attention such a close-up demands. Still, its solidity is executed well and alleviates some of the monotony. Much of the pacing of the swing sequence seems to demand a grander, more inspired payoff that never comes.

Further opportunities for background details are granted through another horizontal pan along the park, this time settling on the not-so-fast approaching Boxer pup. Similar to the pup’s take upon spotting the black cat sign, the Boxer’s reaction when spotting the pup feels underwhelming, music stings carrying more weight than his befuddled head shakes.

Rather, growls and leaping off screen to follow the intruder pull the most legwork.

Through a series of overzealous camera movements (such as the camera trucking in to follow the pup, out when the coast is clear, and back in after hardly a second of stillness to follow the Boxer, making for a rather unsteady and discombobulated lack of balance), we follow the two dogs into a hall of mirrors.

Whereas one would imagine a hall of mirrors segment to dedicate itself to visual distortions and the puppies getting scared of their reflections, such is not the case. Instead, Jones follows a more down to earth route whose payoff feels more akin to a silent film routine.

A sequence of the Boxer dog lumbering along past the seemingly interminable hall of mirrors peters off in its pacing, growing repetitive and droll, but—again—part of it feels purposeful to support the coming surprise. Namely the little pup appearing as the reflection on the opposite side of the mirrors. The audience is forced out of the staged monotony, their befuddlement reflected in the stupefied head shakes from the Boxer pooch.

Lengthy as the coming sequence may be, taking up the next half minute of the short and bloated pauses appearing to further stretch the time, it’s almost earned, seeing as it would birth a routine soon to become relatively commonplace in various Warner cartoons: the mirror pantomime sequence.

Both pups mirror each other’s movements with startling accuracy and synchronization. Curious head tilts, grand acts of absurdity sure to bust the perpetrator—happy panting, galloping, slinking across the floor. The tangible solidity in the construction of the characters furthers the believability, and the synchronization doesn’t falter once unless on purpose. That is, the punchline where the littlest pup gallops past the Boxer and blows his cover, leading to the grand chase.

While the pacing is tiresome and the acting itself could stand a push in a more engaging direction, the sequence is very well synchronized and sets up a solid foundation for further variations to follow; variations that are faster, funnier, more outrageous. Outrageous is not Jones’ objective here, and, as a result, the politeness of the routine fits in the surrounding context of the film.

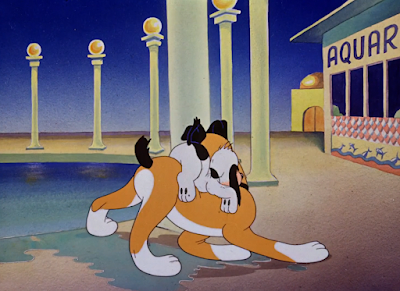

Restrained as the chase up a collapsible set of stairs may be, particularly the lack of speed when the Boxer makes his appearance, the fluidity in the inevitable crash is hypnotic and rhythmic. A smooth camera pan downwards is to thank, as is playful yet impactful sound design to carry the weight of the fall. Economic use of staging, environments, and props tend to be more engaging than the antics themselves.

Such applies to the ambiguous stairs-turned-ramps supplying a makeshift ramp, prompting the littlest pup to slide down and barrel into the Boxer. Boxer pup flips over, tumbles down to the bottom of the arch, and both make belabored eye contact through the courtesy of a close-up shot.

In the review of Sniffles and the Bookworm, I mentioned that a synonymous close-up of the eponymous characters making face to face contact would have been followed by a slow, creeping wry smirk had the short been produced a few years later. I should have said produced a few weeks later—while the motion hardly makes a grand difference, seldom exaggerated and merely the twitch of varying facial muscles, a scowl from the Boxer prompts a facetiously innocent grin from the puppy. It’s pedestrian knowing the variations of the same interaction that would be rife years down the line, but it serves its purpose well here. Strong parallels, confident construction, clear intent in mood and story.

The departure of the curious puppy spawns an intriguing after effect on the Boxer. Rather than depicting his fur rustling from the breeze left by the pup’s exit through restrictive, uneven black outlines, the outlines are removed altogether, prompting the colored brushstrokes to feel like real bristles of fur unburdened by their spontaneity or lack of consistency. Rather than seeming sloppy or unconfident, the result is lifelike and appealing.

Solid utilization of backgrounds and stylization prevails through another silhouette shot of another chase, this time shot at a distance to distinguish it from the first silhouette shot. Not only that, but the settings and environments feel exaggerated as well, height discrepancies keenly noted—the pups seem puny compared to the looming attractions and grand, towering strings of light. Pale choices of color in the background allow the dogs to stand out first and foremost; a true shame that the shot lasts as short as it does, making its artistic showboating feel slightly more transparent. A transparency that is earned, as it is a genuinely striking effect.

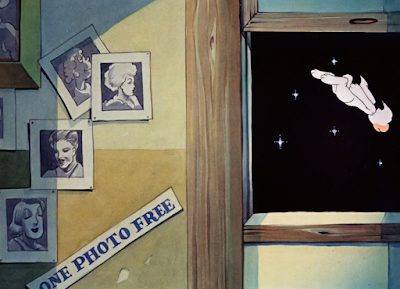

Our story now takes us to a phot booth, clearly indicated through liberal signage and photos on the wall. While Jones’ pantomime cartoons often feel longer than they truly are, their clarity and digestibility is always strong. Intentions of the characters, conflicts, storylines, plot points, gags are all communicated clearly in their set-up. While certain acting decisions may feel aimless and ambiguous—something Jones has rectified as he grows into his role as a director, even if that often means over explaining something as overcompensation—the premise is almost always exceedingly clear. Posters advertising 4 photographs for a quarter eliminate any room for doubt in where the story has taken the pups next. The audience knows to expect gags corresponding to the new setting.

In this case, such gags manifest in the tried and true comically incongruous cardboard cutout standees. More specifically, the littlest pup posing against a purposefully voluptuous figure. Stalling’s brazen, sultry score of “Where, Oh Where Has My Little Dog Gone?” is really the most appealing part of the entire gag, but the visual discrepancy is strong between the two body types.

That too is quick to last. Upon spotting the behind of the standee, the Boxer pounces.

Rather than delegating more focus to bloated, sly expressions of guilt or generally slow beats, the pace takes a turn for the quicker as the pup is promptly tossed out the window. More symmetrical, graphically minded staging persists, this time a wooden beam in the walls splitting the composition into two. One half of the screen is dominated by photographs, the other a window.

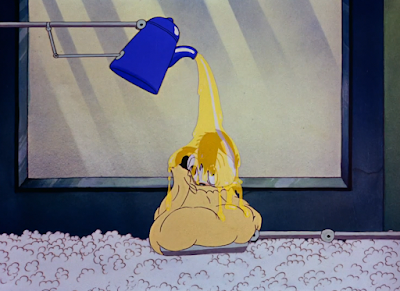

Unfortunately, the fall into a popcorn machine breaks the brief relief in speed—then again, that critique could apply for the entire coming sequence. After an awkward and stilted, rigid fall into the top of the popcorn machine, echoes of Dog Gone Modern are repeated in both the theming of the gags and the excruciating sluggishness in which they’re realized.

Curious head tilts upon entry, loose kernels of popcorn tumbling off his muzzle and into the machine are solid, as are the sniffs identifying the food. It’s the nearly 20 seconds of chewing sounds and belabored eating that’s frustrating in its monotony. Even if the Boxer pup does come up from the other side of the window, prompting the puppy to turn around--chews slowing, turn back around and force the food down--the tedium becomes grating and loses its comedic impact quickly. Thankfully, the drawings of both characters are appealing and attractive, supplying visual buffer.

Stalling’s music continues to carry the most of the weight upon the pup’s frantic exit into the popcorn—quick, frantic music is incongruous with the weightless, floaty, and mechanically even digging.

The Boxer is who kickstarts the Dog Gone Modern comparisons when turning the machine on. Through the aid of robotic arms, the curious puppy is soon transformed into a bag of popcorn. With the benefit of nearly a year between the two cartoons, Jones’ antics here are much more solid and fluid in their action and animation, flaunting meticulous inking skills particularly when the pooch is doused in a hearty helping of butter. Movement feels tactile, weighted—especially when the robotic arms shake the bake of popcorn around, pup reduced to a pile of lumps jostled inside the bag—and is an overall improvement on the predecessor, even if the pacing is still somewhat slow.

Following some awkwardly paced angry head tilts, the Boxer grabs his prey and marches along the park. Further praises are in order for the tactility and weight of the motion, particularly the bag swinging around and bounding along to the momentum.

Jones’ overzealousness with camera movements for clarity strikes again in an unnecessary truck-in of the bag ripping. Not a major detractor, as an excess of clarity is more helpful than the alternative, but a lingering unconfidence still has yet to jar itself loose from the filmmaking. Mechanics of the bag ripping are realistic and attractive, weighted, and continues as such even after the bag empties itself.

More shots that are slightly too long—particularly the Boxer meandering along with the empty bag—are interrupted through barking off-screen, which only then catches the Boxer’s attention.

With the titular pooch loose, his barks are revealed to be directed towards a line of toy cats stacked for a nearby game. The same subtle split-screen approach is executed, the stall taking up one half of the screen and the wall the other.

Embracing the Disney philosophy spawns more arbitrary action for the sake of being arbitrary, but that could be said for much of the picture as a whole. Particularly, the Boxer spotting the pup with his own eyes before digging through the empty popcorn bag, sticking his muzzle through the ripped opening, growing furious at losing his prey, and struggling to remove the bag from his head, spawning a handful of reverberating head takes after the fact. It’s not so much the double take that’s the issue, but the mechanical bloating in the pacing that highlights such maneuvers as transparent and unnecessary.

With the pup catching wind of his pursuer, the chase ensues after too long a pause between the puppy running offscreen and the Boxer coming on.

No matter—more gorgeously painted backgrounds, strategic pans, and height conscious composition as a whole dominate the next portion of the chase. Staging the looming stairway with a rocky façade at a diagonal angle allows the upward, seemingly endless pan to feel even more hypnotizing than just a single vertical pillar of rock. Instead, it almost feels as though the camera and audience are moving in two different directions. Disoriented, the heights of the pup as he skids took the very top of what is revealed to be a slide feel much more extreme and drastic.

Ditto for the staggering perspective shot of the slide leading straight into a pool of water. The foreboding din of a drumroll makes the space feel even more empty and suffocating as a result.

Upon the entry of the Boxer pup, the inevitable occurs as both dogs skid down the slide and into the water, treading on the liquid surface before plunging underwater. Both the sliding and the water skating especially glide in their pacing, easing the climax and making it feel a little too relaxed as a result, but the effort is appreciated. Comparisons to The Good Egg arise in the manner of which the pups both unceremoniously plop into the water—thankfully, no “ta-da!” music sting is present to erase the desired vulnerability of the sequence.

Thus, a momentary truce is born as the Boxer comes to the surface with the pup unconscious on his back. Rather than delving into a heartwarming tale of the two becoming buddies and free to romp around the park as they please, the Boxer’s saving of the pup is purely accidental; head shakes and looks all around reveal his cluelessness.

It’s only until the pup is sent rolling off the Boxer’s back that they make eye contact. That too results in a growl—a much more entertaining route than the alternative. The Good Egg already scratched that itch for cloying tales of heartwarming friendship. No, more chases and comedy are a much stronger priority.

More head shakes of disbelief (outfitted with a bulging eye take to somewhat ease tedium) segue into the next piece of business that Jones would refine and fine tune in his Toy Trouble not even two years later. Through the gods of convenience, the littlest pup manages to use a shelf of identical toy pups as a means of effective camouflage.

Jones’ example in Toy Trouble is more amusing, largely in part due to comparatively streamlined pacing and perhaps a larger threat, but mostly because of the incongruity; Sniffles makes a desperate attempt to blend in with the Porky toys, despite appearing nothing like them and blowing his cover more than once. Still, the cat that pursues him pokes every single toy that releases a squeak, suspense thickening and placing heavier pressure on Sniffles.

Here, the pup is indistinguishable from his manufactured peers. No certain approach is the right or wrong way to go about it—different contexts bring different demands, and that the audience is just as clueless as the Boxer pup here inevitably draws us in towards the action. We too want to figure out where he went. A perspective shot of the toys framing the barking Boxer is particularly solid.

The altercation of the Boxer bowling down the toy stand comes after a few more barks and growls, trying so desperately to cling to believability and Disneyesque acting when it, more often than not, comes as a hinderance. Regardless, mechanically even and slow as the actual explosion may be, the mischievous gruesomeness of disembodied puppy heads freely rolling around on the ground is certainly not lost.

No dice—just a torn pile of stuffing. The vulnerability of the Boxer pup is shared openly with the audience, appearing as though he might cry. Such is indicated through aimless, vacant head bobs towards the screen.

Plucky barks a short distance away and another startled take from the Boxer clue that he has reason to be upset. Indeed, near the conveniently marked exit stands the titular curious puppy wagging his tail with polite, provoking inquisitiveness.

And provoking it is indeed, for the Boxer engages in another series of growls before pouncing at his seemingly harmless foe. A rather sluggish, weightless brawl concealed by dust clouds erupts on screen as a byproduct. Again, Stalling’s musical orchestrations and Treg Brown’s rummaging sound effects pull the most legwork.

Somewhat anticlimactic as the reveal is thanks in part to the equally anticlimactic brawl, the Boxer turning his head to reveal the pup safely out of the park’s gate and wagging his tail is serviceable and cute. That the dust hasn’t even settled yet adds further insult to injury, and the somewhat lengthy pan conveying the distance between the two exaggerates and notes the speed in which the pup made his exit.

We are met with one final gratuitous camera truck-in and one final gratuitous fit of growling as the Boxer heaves in red hot anger…

His pathetic deflation somewhat deflate the impact of his manly, visceral sobs, driving a wedge between the spontaneity of the shift, but the transition is still nevertheless strong enough to close out on.

Though without the '30s we wouldn't have the golden periods of the '40s and '50s, I still believe their highs were rarer and constantly concealed by weaker streaks of shorts.

ReplyDeleteThe constant singing first and the schmaltzy tone then were the main reason for my bias before rewatching them. Also impressive how Clampett is the only main director to release his first breakthrough a year after his promotion, whereas the other big ones would need years and years to achieve their best form.

Been reading your articles for a while, keep up the good work.