Release Date: December 16th, 1939

Series: Looney Tunes

Director: Bob Clampett

Story: Bob Clampett

Animation: Norm McCabe, Vive Risto

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Porky, Cuddles, Cold Promise, Professor Widebottom, Silver, Usher), Billy Bletcher (Lone Stranger, Narrator), Robert C. Bruce (Narrator), Arlene Harris (Woman), The Rhythmettes (Chorus)

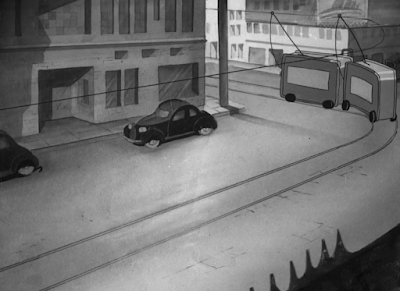

It seems almost fitting to end the 1939 Looney Tunes year out on all of the Clampett clichés: stagnant establishing shots (paired with the signature foreground overlays parting as the camera trucks in), sign gags evoking polite groans through their punny wordplay—a film entitled The Broken Leg is touted as being surrounded by a large cast—and a saccharine chorus outfitted to “There’s a Brand New Picture in My Picture Frame”, sung by the ever-reliable Rhythmettes.

A shot of sardine cans representing a streetcar is clever mainly through its playful faithfulness. Instead of merely demonstrating the visual of passengers packed into a streetcar like sardines, or even chancing a quick cross dissolve between a streetcar, can of sardines, and back to a streetcar, the sardine cans follow the lines of streetcar logic dutifully; they are attached to a cable and go along a track, come to a curt stop, allow their passengers to disembark through uncurling the can and precede onward.

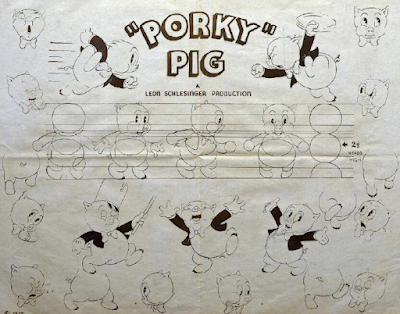

A lack of questioning on part of both the filmmaker and the characters onscreen consider it instead a piece of the mischievous [un]normalcy in Clampett’s world. Even the seemingly menial designs of the ensemble evoke Clampett: dot eyes, spherical constructions and loose, rubbery necks are comparable with the design sense rampant in Porky in Wackyland, a short rife with his sensibilities at the time in every possible way.

Further praise for character design in this cartoon stems from variation—a shot containing a long line of children cramming into the theater boasts species of all kinds: cats, dogs, mice, rabbits, ducks, geese, and even a Porky lookalike wedged in the back.

A mouse pausing to take a gander at the “KIDS ADMITTED FREE” sign not only acquaints the audience with the premise, but indicates that it’ll be a point of interest in the future. If animation and backing musical orchestrations are dedicated purely to a character looking at a sign rather than advertising the event in passing, we are meant to pay attention to its hook.

Thus provides ripe opportunity for a natural antithesis; one that is snooty, arrogant, uptight. Character designs in Clampett’s cartoons have a solid tendency to be informative, and the pompous woman walking her equally egotistical pooch prove no exception through their rigid stature, slow movements, and decorational embellishments; a lorgnette for the Missus, a ribbon tied to its tail for the dog. Lugubrious musical orchestrations of “Thru’ the Courtesy of Love” further their purposeful rigidity.

“Movies?” Still ironing out the smoothness of their transitions, the camerawork suffers from vestiges of shakiness as it trucks into the woman—we are meant to give her our full attention. “We nevah go to moo-vies.”

She turns to her dog for moral support. “Do we, Cuddles?”

Equally conceited head shakes are exercised by the humiliatingly named Cuddles. Excess wrinkles in its muzzle seem to bring attention to further egotistical tendencies—wrinkles tend to signify age, which signifies wisdom, which signifies that this dog is old and knows its way around the block and to argue would only be of the utmost futility. Posters advertising Looney Tunes are given a shoutout in the background; more can be seen at the rightmost corner of the theater entrance.

The pompous woman and her equally pompous dog go on their pompous way (pompously) past a sign advertising The Valley of the Giants (A Story of the Big Trees)—a nod to the 1938 Warner film of the same name starring Wayne Morris and Claire Trevor. I regret to inform you that the tagline is not also shared.

Close shots, diagonal angles and relatively dynamic compositions as a whole occupy numerous sections of the cartoon, and this scene is another contender. Both the sign and the dog are meant to be the center of the attention; its owner is irrelevant. Structuring the sign to accommodate the dog’s height indicate an association between the two. Cuddles loyally follows his owner…

Until we indulge in the classic breakout formula of screwball hysterics, guttural “LOOK! LOOK! TREE! OH BOY!”s from Mel Blanc intertwined between frantic barks. Lingering on nothing but the sign before the hysteria seeks to trick the audience into thinking we are above “dogs pissing on tree” gags—absolutely not. Likewise, the pause allows the transformation in tone to feel more abrupt and spontaneous than going through the liberty of showing it on-screen.

Normally, the completely different model of Cuddles as he revels in the throes of crazed ecstasy would seem jarring, as he looks completely different than before (to the point of abandoning the ribbon on the tail)—instead, it proves beneficial. The transformation in design is indicative of the shift in tone and personality, and even though the ribbon loss does appear to be an error, seeing as it returns in the following sequence, one could interpret it as a symbol of Cuddles’ freedom. No longer shackled to haughty façades!

Cuddles’ “C’MON BOY!” to his owner is a great indication of the power imbalance switching in his favor. If that wasn’t apparent enough by his dragging and pushing of the owner, grabbing her by the hand and dragging her inside the theater whether she likes it or not, then subjecting her to stereotypical, literal pet names is. He is now the master.

A side note, Clampett manages to tease the censors by having the woman halt in front of a window display of lingerie; due to the deliberate vagueness of the brushstrokes and light values, it’s somewhat difficult to see, but the aid of freeze framing today works in our favor.

Only two minutes late into his own cartoon, a diagonal wipe segues into Porky’s introduction—my personal favorite part of the entire cartoon.

With animation dutifully reused from The Daffy Doc, changes only presiding in the added lip sync, his eyes now tracking the coin in which he flips, and the decision to have him stuff his hands in his flesh pockets rather than the pockets in his jacket (and if that was a conscious decision and not a mere misinterpretation of the source material, praise be), Porky strolls along while reciting the mantra undoubtedly told by his mother so as not to forget it.

That we immediately cut to him walking and muttering his recitation of “A eh-leh-loaf a’ bread, a bottle a’ milk, an’ come home right awuh-way... a luh-leh-loaf a’ bread, a beh-buh-bottle a’ milk, an’ come home right away… a luh-leh-loaf a’ bread, a-a buh-beh-bottle a’ milk, an’ come home right away…” indicates he’s been repeating this to himself for quite some time now. Likewise, the vocal direction is low, almost stilted in its rigidity—a major plus, as the stiffness of his recitations perfectly convey his steely, forced concentration. He struggles to get the words out not from the stutter, but from the burden of responsibility, as though each word is precious and to excise this process will result in a loaf-of-bread-and-bottle-of-milk-catastrophe.

While the dialogue is naturally asynchronous from the source material, the end product feeling somewhat skewed and unbalanced, such a disconnect seems to work in Porky’s favor. It conveys a vacancy that translates into the toil of his concentration, as though he can’t even afford to emote or maintain a proper lip sync—remembering shopping lists comes first.

All of the above apply to Porky’s brief mixup of “A luh-leh-loaf a’ milk, a bottle a’ buh-bih-bread, ‘n come home right away.” Normally, such a switch would be employed with the stutter in mind (such as Porky asking Petunia if she’d like to go to the pic and have a parknic in Porky’s Picnic), but here it is all a result of mindless, determined, childlike recitation. A conscious acting decision to poke fun at the charming absurdity of his monologuing.

Likewise with his mutterings of ““A-a loaf a’ beh-eh-bread, a bottle a’ mi-eh-meh-milk, an’ keh-ckeh-kids admitted free,” upon passing the front of the theater. The brief head turn spared towards the sign is a great touch—like the entirety of the sequence thus far, it is an action that reeks of believability and natural, subconscious quirks. Making Porky stop to read the sign word for word and continue on his way would abandon the momentum so meticulously established by the rhythm of his recitations.

Not like the opposite is ever an occurrence, but copious praises must be sung yet again for Carl Stalling’s orchestrations—this time a plucky accompaniment of “Sticks and Stones”. It offers a cute piece of continuity; a similar arrangement of the same song was utilized in the opening of Porky’s Picnic, whose tone and prioritization of endearing, naïve and likable charm from Porky is synonymous to the introduction here.

Moreover, Stalling’s subtleties allow for a richer all encompassing experience. While the crescendo in the music is the most obvious upon Porky’s added mutterings of “kids admitted free”--indicative of the rising excitement sure to reach a boiling point--musical flourishes following the action are just as beneficial. While his orchestrations in The Daffy Doc granted a flute glissando with each toss of the coin, here, a very subtle violin glissando follows the sweep of Porky’s arm every time he reaches to catch the coin. It only happens twice, but is such remarkable attention to detail that seems menial on the surface level, yet enriches the entire scene tenfold.

Indeed, the crescendo in the music hinting towards a climax follows through in its promise upon Porky’s bewildered proclamation of “KIDS ADMITTED FREE!?”

The animation is rigid and crude in its portrayal as Porky scrambles into the air, and the same could be said for the beat dedicated to him running in place, but both do not hinder the spirit nor intent of the scene in any way. Even something as seemingly basic as the volume difference between Porky’s circuitous mutterings and his yelling at the camera propel the shift just fine.

Whereas Porky’s histrionics of the delayed running take, zipping back to the front of the theater in front of the sign, and cheeks flapping prominently as he wobbles back and forth in his place does have potential to dip into territory that is coy or redundant, here it is logical and endearing in conveying his unbridled ecstasy.

His excitement transcends the screen—he can’t believe it! Whereas most kids see the sign, perk up, and file in line, Porky does a double take, struggles to get his legs moving because he’s so thrilled trying to process the opportunity, zips right back to the sign itself rather than squeeze a spot in line, and even goes so far as to wipe his eyes (endearingly accompanied by another very subtle but fulfilling musical flourish from Stalling) as though he truly cannot comprehend the joys of free film patronage. A free film patronage exclusive to him, at that! Kids admitted free! Not adults, kids! He’s a kid! The novelty is all the more cherished. Moments like these that embrace Porky’s sentimentality rather than framing it as a point of weakness succeed in their ability to be just as funny as the latter. Cynical as the latter interpretations may be (and funny), the unabashed glee radiated from the sequence here presents its own unique charm.

Likewise with the twirling take he does after allowing the words to sink in. Willfully mechanical, the purely purposeful motion—rather than an act of unconscious impulse—succinctly caricatures his thrill. An amalgamation of mystified ecstasy all manifest in a simple, drill-like twirl before rushing into the theater.

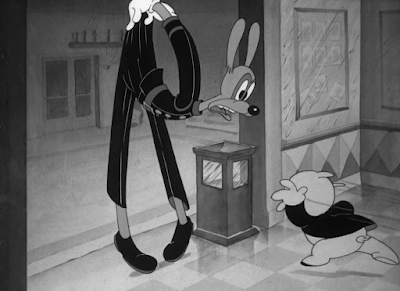

An added twirl weasels its way into the dust trail inducing run as he rushes beneath the usher’s legs. It absolutely is an unnecessary detail, but one that acknowledges and celebrates such arbitrariness. Pure feeling and raw excitement are dominant more than logical or physically grounded decisions. It’s a gesture that barely even translates on screen due to how quickly it occurs, but it provides a lovely addition nonetheless. Visuals of the usher lifting his butt up to part his legs garners inspiration from The Lone Stranger and Porky.

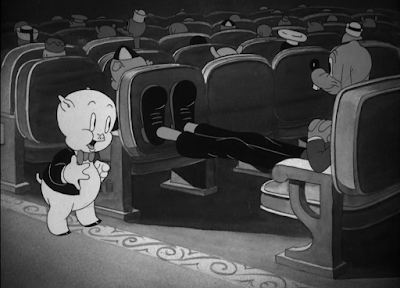

It’s a shame that the remainder of the cartoon doesn’t nail the same charisma consistently throughout its duration, but 7 minutes can’t realistically be dedicated to Porky reading signs. Instead, the viewer is finally taken into the theater courtesy of Porky. His mad dash continues up the aisle, so much so that he has to skid to a halt and rush back into frame to nab a seat.

Aisle blockers guarding the seats with their legs are swiftly taken care of as he pushes a dog’s legs like a door; engaging perspective animation of the feet swinging in the foreground paired with Treg Brown’s creaky door both benefit the illusion well.

Enter the spot gag portion of the cartoon, dedicated purely to newsreel parodies, situational gags surrounding the context of the segment, and punny wordplay betwixt said segments. Clampett would later place a more immersive twist on the format by having some of his own cartoons be entire newsreel parodies (such as Porky’s Snooze Reel, Nutty News, and Meet John Doughboy, the latter of which providing a brief introduction separate from the film within a film.)

For now, much of the inspiration behind the format uses Friz Freleng’s She Was an Acrobat’s Daughter as a foundation—so much so that the establishing portions of the newsreel are directly lifted from the aforementioned cartoon. Rather than billing the reel as “Goofy-Tone News”, Clampett equips the more appropriate “Looney-Tone” name. Both are a take on Fox’s Movietone News, narrated by Lowell Thomas—“Cold Promise”, as he is billed here, is even further of a stretch than Acrobat’s “Dole Promise”.

Acrobat was more abrasive and somewhat more subversive with its humor—in the original opening, “Dole” has to have his own name whispered to him from an offscreen assistant, establishing the immediate disestablishment of any sort of purposefully misleading authority. While repeating the same gag verbatim here would be unnecessary, Freleng’s application of the parody format feels more rooted in sincerity rather than Clampett’s. Then again, the footage in The Film Fan is borrowed without much of a second thought, so such is bound to be its fate. Still, much of this surface level sense of parody presides through the run of the cartoon and lacks the anchor that Acrobat has.

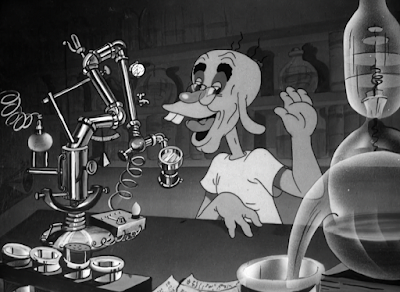

More politely amusing then, aggravating now late ‘30s Clampettesque wordplay persists through the news headlines, as they will all through the picture. A story located out of Eightnine, Tennessee (get it!?) notes “Scientist Discovers That Short Tempered Doctors Always Lose Their Patients”—this has nothing to do with the following sequence.

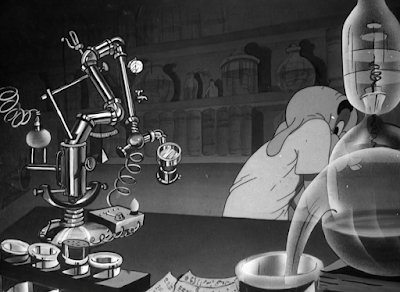

That the mysterious, balding figure we’re introduced to is considered a professor (billed as Professor Widebottom, of course) is the only possible adjoining factor connecting to the prior headline about doctors. Instead, Blanc’s stolid narration indicates to the audience that the professor has perfected his “superprismatic” microscope. Discrepancy between light and dark values are strong, allowing the light coloring on Widebottom to pop and read clearly against the black, droll, esoteric laboratory background.

“By observing closely, you can see for the first time in scientific history germs in the human bloodstream.”

A series of somewhat elaborate camera maneuvers prove to be the most intriguing aspect of the entire sequence. As Tex Avery did in The Mice Will Play, the lens of the camera focuses onscreen to mimic a microscope coming into focus. Unlike Tex Avery, the iris surrounding the scene to mimic the microscopic view is widened and abandoned. While that in itself does promote stronger visual clarity, novelty in the microscopic theming is lost.

On par for Clampett, the germs resemble insect adjacent creatures frolicking in the bloodstream as though it were water. Purposefully infantile, cloying squeaky voiced quips of “Oh boy, oh boy, oh boy!” and “Yeah, this is a lot of fun!” overlay the various aquatic activities; a ship labeled the S. S. Malaria is an obvious choice, but amusing in its implication that the human bloodstream has its own economy run by bug-like germs. The sequence does, however, drag on longer than what is necessary—the same point and impact could have been made in half the time.

Dissolve back to the professor, in which the narrator congratulates the professor on his invention.

“Awwww, huh huh huh, it t’ain’t nuthin’!”

It is always a guarantee that characters with steely demeanors in Clampett’s cartoons are, in fact, “a huh huh”ing dopes in disguise. A careful attention to detail on the warped perspective of Widebottom’s glasses and the coy guffaws bashfully hidden through the barrier of his shirt slightly elevate the reversal beyond the same old same old.

A return is made back to Porky, squinting at the screen through some admittedly ugly but hilariously visceral squints. To Clampett’s credit, he doesn’t abandon Porky completely in the dust for the cartoon—the short makes a point to check up on him intermittently, and almost to a detriment with certain shots that are held too long or unnecessary in their inclusion. More on that later.

For now, the audience is gifted with a great perspective shot of Porky’s point of view from the back row. Perspective on Porky in particular could benefit from more faithful construction, as his ears are drawn on the side of his head rather two dimensionally and are buried by the shading, making him appear bald[er] at a glance.

More intriguing than that is the content on the film screen itself. With the screen as small as it is to purposefully warp the perspective, exaggerating Porky’s plight, no audience member in 1939—or even today in a passive viewing—would have caught the typography on the screen. An intimate zoom in on the screen reveals lettering that appears to say “LOONEY TOON — PORKY’S LA STAND”. Porky’s Last Stand is the next cartoon directed by Clampett to release after this one; it isn’t unheard of for these shorts to reference past cartoons (such as the dig towards Jungle Jitters in The Ducksters, the short mentioned by name as being produced under “Obnoxious Pictures”), but very rarely—if ever—has a short purposefully alluded to a cartoon still pending release by name.

Sequences that prioritize Porky’s youthful personality and all of the humor that resides in such potential are the some that seem to perform best out of the entire short. Exhibit A: the unadulterated panic in which Porky scrambles out of his seat to engage in a hilariously frenetic waddle-run up the aisle of the theater and throw himself in a front row seat.

From a passing glance, it almost feels unfitting and discombobulated in its direction, disgruntlement in visual difficulties seeming to morph into inexplicable, unbridled excitement. Perhaps that’s the beauty of the sequence—its spontaneity. The rigidity, the abruptness, the frantic, seemingly inexplicable motive, and the delivery as a whole don’t exactly need a logical explanation. He can’t see. He scrambles up the aisle to get a better view. All is well, even if a completely arbitrary amount of energy is dedicated to such a menial task.

Clampett’s characters must always fire on all cylinders; the scene exceeds greatly in its energy, and that’s all that matters. Stalling’s frantically jovial accompaniment of “Frat” perfectly represents and compliments the unprecedented fervor.More cribbing from Acrobat is employed through yet another equally exaggerated point of view shot from Porky crammed in the front row, the only additions being the two ducks on either side and “Teabiscuit” replacing “Morphine” in the headline and the location in which the story takes place.

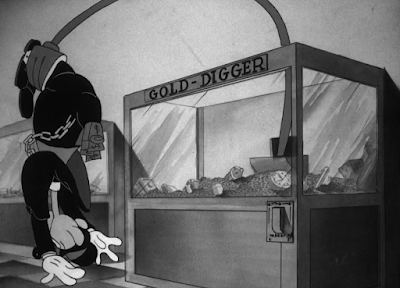

Thankfully—unlike the earlier headline about doctors—the next punny storyline involving retired baker J. Pretzel Pumpernickel never spending a penny despite no longer kneading the dough is intrinsically tied to its adjoining animated segment. Armed with a triumphant, at times sardonic score of “We’re in the Money”, dopey Pumpernickel stumbles upon a claw game and opts to try his luck. Wads of dollar bills prominently stuffed in the back pocket are a nice, incredibly obvious indicator of his wealth if the headline nor three piece suit weren’t enough.

Always intriguing is it to spot early variations on gags and jokes we’ve been well familiarized with in the modern age—in this case, Pumpernickel fishes a nickel in the coin slot, only to snatch it back for himself thanks to the string it’s tied to. Animation of his hand follows a solid smoothness and rhythm that indicates pompous flair, whether it be from the daintily extended fingers or the snappy wrist flicks in which he moves.

Thankfully, the nickel tied to a string isn’t exactly a major point of focus, but more a means of transition. Instead, it provides a buffer as the real crux of the sequence follows the claw grabbing Pumpernickel and dumping the copious amounts of riches from his pocket into the aptly names Gold-Digger game.

Carefully controlled timing allows the gag to thrive; for a few seconds, the slow motions of the crane and mechanical whirring deceive the audience into thinking that Pumpernickel will be rewarded for his trickery. The motion of the claw grabbing his ankle could stand to be somewhat faster and less even in motion, but the variation between the energy and fluidity in both animation and music score earn a rewarding punchline. Strong arcs from the claw that form clear frames around Pumpernickel promote visual clarity and dynamism.

Enter one of a handful of gratuitous Porky shots. While it’s a nice gesture, attempting to keep him relevant to the short somehow, he would fare better without being shown at all—it reads as artificial and feels awkwardly shoehorned to remind us of his relevance. At least for this shot he has the added benefit of animation, even if said animation is just a few blinks. Further shots appear more stilted.

Further shots such as this one as Robert C. Bruce narrates a handful of coming attractions on the big screen; the slightly upward angle in which the scene is composed attempts to appeal visually through dynamic, engaging perspective, but the effort as a whole is lost due to the uncanniness in which Porky and his fellow moviegoers stare blankly at the screen for 6 seconds straight. Vacancy in his facial expression is a side effect rather than the purposeful blankness utilized for comedic potential in his introduction.

Movie parodies and adjoining taglines include shout outs to Four Feathers, Honeymoon in Bali, The Old Maid, and Gone with the Wind (dubbed as Gone with the Breeze, complete with a headshot of T. Hee’s Clark Gable caricature from The CooCoo Nut Grove.) All very barebones and surface level in their presentation. Further gratuitous Porky shots ensue.

For the next piece of business, Clampett borrows liberally from himself; nearly half a minute is dedicated to reused footage from The Lone Stranger and Porky. Colors on the Stranger have been switched to black for clarity purposes, Silver now named Sterling, but little else is different. Billy Bletcher returns as both the Stranger and the narrator—his purposeful voice cracks in the narration and generally inspired deliveries alleviate the monotony. Like much of the film, it’s all a case of “nobody in 1939 would have realized this was reused anyway”, and the application here feels somewhat less lazy than other instances in the cartoon, but is still tiresome regardless.

Thankfully, the entirely new sequence in which the Stranger and Silver split paths is one of the most compelling sequences of the newsreel yet. Somewhat disappointing as it is that the Stranger now has hair—his oddball, bald appearance in The Lone Stranger and Porky seemed to embrace the absurd tone of the cartoon and shared that mischief, but is understandable here considering the intents and tones of the parody are meant to be different—that doesn’t at all detract from the playfulness that follows: directions from the Stranger to take the high and low road spark an impromptu chorus of “Loch Lomond”, better known as “You Take the High Road and I’ll Take the Low Road.”

Bletcher and Blanc both do a great job on the chorus, Blanc especially nailing the potent cheesiness of the outburst. It’s almost a shame that his verses are interrupted through asynchronous neighs—his voice for Silver is relatively synonymous to the future Bugs Bunny in its nasal register.

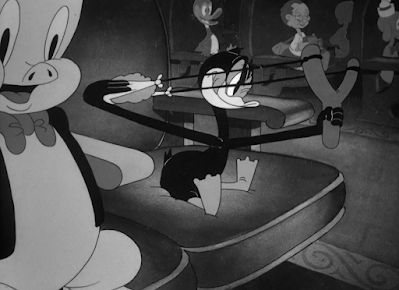

John Carey animates the adjoining shot of a duckling aiming a slingshot at the screen. As always, Carey’s poses are appealing and solid, clear—Porky appears a bit uncanny in the foreground as his eyes aren’t focused on the screen, making him look mindless and vacant, but his construction is strong and proportions appealing enough to grant a pardon. Background characters are also of note, particularly the Daffy lookalike and the random human who is almost certainly a caricature of someone on the Schlesinger staff—of whom, I am unsure.

Clampett’s imitations of She Was an Acrobat’s Daughter scratch beneath the surface level and finally achieve the appeal of the source material: the subversive humor. When the wad of gum hits the screen, Silver reacts to the hit as though he truly felt the impact. That Stalling’s musical accompaniment lingers for a few bars after Silver drops out of the ongoing chorus indicates an embrace and exaggeration of the spontaneity, as though even the orchestrators are caught off guard by the switch.

Regrettably, the momentum of that high doesn’t last. Clampett places a heavier focus on the duck in the crowd, innocently whistling as he hides the slingshot behind his back. Cute, yes, but deflating in a scene that hungers to prioritize comedy first and foremost. Silver’s “Who’s da wise guy? Who’s da wiiiise guuuuy?” are all that's granted in terms of confrontation, and half of that is just audio laid on top of the shot of the duck. Had a director like Tex Avery been in charge, the relationship between characters on the film screen and in the audience would have had a much greater priority with a much greater outburst from Silver. Here, that relationship between duck and horse feels disconnected and somewhat stilted.

Cross dissolves to the usher shown before indicate yet another shift, an end, a resolution—we have moved past our quota for newsreel gags. Instead, we root ourselves back in character acting and story first and foremost. All of that is sparked by a telephone call—the dog’s ear curving over the ear piece is a wonderful little exaggeration of clarity that passes itself off as a menial gesture. Strong framing over the ear piece, guiding the eye towards the usher’s line of action, is equally appealing as it is funny.

Keen directorial timing from Clampett and keen animation timing from John Carey allow the incomprehensible outburst on the other end of the phone to thrive through deliberately belabored pauses and stiff posing. The elasticity in his movements as he throws his hands in the air or even the breach of decorum heard in the shakes of his voice all provide a strong antithesis to the quiet, purposefully unassuming setup just seconds before.

A “Yes, Mrs. Pig,” inserted in the usher’s trembling reassurances provide all the context we need to know. Not a single word on the other line of the phone has been comprehensible, but the conviction in the emotion has. Porky’s devoted mutterings of the shopping list weren’t a transparent piece of character acting or filler—they meant life or death.

Further attractive, slightly unconventional composition can be seen on the usher standing on the theater stage. His hands momentarily grazing the foreground when raised further the depth and immersion of the staging, giving a tangible weight to his presence and movements.

“If there is a little boy in this theater who was sent to the store by his mother, he’d better get home right away!”

His commands are just vague enough to work. Recovering from momentary eyebrow loss, Porky is subject to the humiliating walk of shame as he gulps, slinks out of his seat, and braces for the worst. Stalling’s music coming to a complete halt and replaced only with a deafening silence add further gravity to the situation and allow the shame to thicken—not even ambient music shall serve as a detractor away from Porky. All eyes are on him.

Interesting to note is the variation in attitudes compared to the beginning and end of the cartoon—rather than jumping up and engaging in a fit of hysterics that scream “I forgot” before rushing out the door, Porky’s walk and demeanor as a whole is much more subdued, ashamed, lugubrious—a great contrast to his introduction where he was nothing but a propelled force of energy. Since he knows grave consequences await him at home, prolonging the time in which he must face them is more ideal than engaging in a mad dash.

Instead, the rest of the theater does that for him. Purposefully vague wording from the usher works in everyone’s favor as the entire area is quickly evacuated from children with all kinds of guilty consciences. Instead of Porky matching their pace by eventually running himself, he instead gets pushed out of frame.

Varying intervals in which the kids leave ensure the visuals are engaging and promote a slightly stilted lack of balance to feel natural in its spontaneity. All of the above apply to the varied reactions from the different kids--some rush out of their chairs right away, some do straightforward takes, other do a head twirling take. One duck in particular even has to be lugged out of his seat by his brother amidst his daze.

Clampett stages and divides the action beautifully between kids and the usher—every single emotion and intent is clear and concise. With so many characters packed in one single frame at such a far distance, that is an incredibly difficult feat to pull off.

Fervent orchestrations of “Home Sweet Home” are as endearing as they are spirited—Stalling strikes a chord that is wryly sentimental, sincere in its delivery but possessing a lighthearted, riffing commentary. Especially when the music seeks to accompany the visual of the theater literally deflating as its patrons complete the mass exodus; the sign on the roof advertising a grand opening add further insult to injury on its decrepit status.

Such a wonderful and clever, attentive detail: despite being at such a far distance, the lone straggler is immediately recognizable as Porky. A quick, aimless run in circles before scrambling home ensures the audience catches his appearance. Indeed, it cements a solid finality; the building, already appearing to have collapsed, folds into itself to one last further extreme upon Porky’s exit. That’s all, folks.

.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment