Release Date: December 16th, 1939

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Tex Avery

Story: Tubby Millar

Animation: Virgil Ross

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: John Wald (Commentator), Mel Blanc (Coach, Papovich, Players, Commercial Announcer, Cheerleaders)

Avery’s penchant for misleading the audience manifests itself first as early as the opening titles. Beneath the credits lies rotoscoped footage of a football game, players and yard lines silhouetted against the screen. Typography dissolves to delegate full attention to the action, following a player tackling the other…

…and ending with a mallet to the head. Even the movement and timing of the animation seeks to trick the viewer—the impact of the mallet hitting the player and said player collapsing to the ground is timed much quicker and more abrasively than the purposefully glacial rotoscoping. If the cartoon’s title wasn’t enough of an indicator, this little action is; this is not a game to be taken seriously.

Iris in to the stadium, introduced by our narrator as the Chili Bowl game. Curiously, said narrator does not sound like Avery’s usual regulars of Robert C. Bruce or even Gil Warren. Despite this, and as to be expected, the general intonation is the same. Politely condescension oozes from his every word.

“The weather is perfect this afternoon for this great event. In fact, there’s only one small cloud floating in the sky.”

Little time is spared before the camera jolts up to reveal a menacing storm cloud, lightning strikes imminent. Sharp timing between the pan and the lightning strikes further the surprise aspect of the reveal, abruptness necessary for the literal shock demanded by the gag. Carl Stalling’s brief sting of William Tell’s “The Storm” blankets the joke in a familiar, accompanying irony.

Comments on the “colorful crowd” set a precedent for the short’s priority; corny puns and wordplay are given heavier emphasis here in this particular cartoon. As per usual, Avery’s looseness and acknowledgement of the stupid puns allows these shorts to be more watchable—he doesn’t try to pretend like this is the pinnacle of comedy. Promptness in his delivery and little lingering allow the novelty to seep in stronger.

“The huge bowl is filled to overflowing!”

Delegating varying, sickly hues to different parts of the crowd allow for the visuals to embrace their grotesqueness. A single toned brown blob doesn’t convey the same repulsive malaise as the multiple hues of black, brown, and tan. Constant movement of the spectators render it synonymous to a disgusting, moving creature.

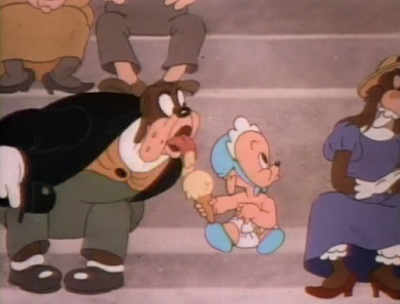

Charlie Thorson provided character designs for the cartoon, which is particularly noticeable in a rotund, dapper dog hungrily observing a baby licking its ice cream. Twiddling thumbs and patting knees indicate restless pondering.

The follow through in the dogs jowls once he turns away at the baby’s notice add a lingering second of guilt, a reminder of his intentions hanging in the air. The same could be said for Stalling’s quick musical sting that accompanies the motion.

Same charade is repeated twice before the dog gets down to the goods. That the baby doesn’t notice indicates we’ll be following these two for awhile—too easy of a victory. Too anticlimactic of an end. Avery has an end goal in mind.

A handful of aspects in this short are borrowed and retooled from Avery’s previous material, the first example being a reflex gag. Borrowed from Porky the Wrestler, in which a referee hits his knee to prompt his leg into kicking the wrestling bell, an assistant hits the kicker’s leg to prompt a handful of field goals. Naming of the kicker—Stinkovitch—also follows Wrestler’s peculiar naming conventions and the humor therein; many of the players’ names here are reminiscent of Avery naming the former cartoon’s challenger Yakinowskiokiwoskioski (and the multiple variations that follow.)

Likewise, a line of kickers breaking out into an impromptu chorus line and effeminate dance is not at all a concept exclusive to Avery, but the grounded animation, design, and motion in which it is applied allows the absurdity to be embraced far stronger than the limitations seen in prior examples.

A shared nod between the kickers before breaking out into the number bestows a naturalistic quality that reminds the audience this is happening, it is a process with thought and purpose behind it. Solid construction (flaunted particularly strongly as the kickers all dance in a circle) enhance the depth and add further believability, all wrapped under a degree of caricature that render the motion curt and appealing. Dutiful musical timing—especially the final three notes—further complete the image. A succinct example of the success in Avery’s joyous stupidity.

Elsewhere, Charlie Thorson’s design sense is further concentrated in the referee, practically identical to the Mountie in Snowman’s Land. His dopey demeanor continues to permeate the screen just from his looks alone. Here, he beckons both teams to come into place for the coin toss…

Obvious as the punchline of the players wrestling over the coin is, the spontaneity in which the free-for-all unfolds and the facetious background accompaniment of “We’re in the Money” render it more mischievous in tone rather than routine. Erratic looseness of the motion itself signifies just how far Avery has come in perfecting his sense of speed and timing—such a scene would not have been possible a year or two prior. A handful of shots are held for two frames with the exception of one or two characters, adding a more natural, less orchestrated rhythm to the animation that, in turn, makes it feel all the more chaotic.

An overhead view of the teams lining up provides a brief buffer back into reality before segueing into the next piece of screwball business. A balance between playful and menial is necessary for the playfulness to read stronger.

Per the narrator’s excited proclamation, the referee blows a bird shaped whistle, results mimicked in the sound. An abundance of spit is produced as a result; slightly gratuitous is the pause that follows, focusing on the dopey dog’s grin, but it isn’t nearly long enough nor noticeable to prompt a conniption. Just disturbs the very delicate rhythm necessary for the energy demanded by the game and tone.

Cue the kickoff. Diagonal composition and perspective animation add newfound depth to the scene, evoking a tone that is more serious and demands more audience attention…

…only to be shattered as the kicker punts his teammate rather than the ball. Glacial as the action of the kick may be right before the impact, the punchline lands hard thanks to the nonplussed and GRADUAL reactions of the kicker. Not an instant realization, nor an instant solution—he only scratches his head in thick befuddlement.

Decisions to focus purely on the reactions of the kicker cement the solidity of the joke; kudos to Avery for restraining against following the kicked teammate. We never see him again nor follow up in his condition. That is where the beauty lies.

“Listen to that crowd roar!” Hastiness in which the lion roaring sound effects are added over the cheering crowd footage is funnier than the roar itself.

Narrator provides us the liberty of telling us that the referee has called a redo of the kick rather than dedicated a belabored scene depicting the same action. Audiences receive the same amount of context regardless, and it’s not the referee who is the focus, but the players. Stalling’s music score of “Frat” shifting from brazen and triumphant to domestic and flighty signals antics are upon us.

Indeed, Avery engages in a classic reversal—the kicker is soon transformed into a baseball bat-golf club hybrid as his teammate grabs him by the legs, angles the driver, and swings.

A strong silhouette on the kicker is the most noticeable plus of the illusion, but the attitudes conveyed through the delivery are also pivotal for its success; both the kicker and his teammate act as though this is a normal occurrence. No befuddled reactions from the kicker as he’s transformed into a blunt force object. Careful alignments of the club/bat follow the philosophy of the head shakes shared between the prior chorus line—little, believable pieces of acting like those ground the action and stress the absurdity through everyday quirks witnessed in real life. Copious amounts of dry brush forming a solid, arcing trail further enhance the speed and impact of the entire hit.

“It looks like Smellovich is going to get it in the end zone!”

Like most of Avery’s gags, the matter of fact delivery in which the opposing player kicks the receiver point to its success. No grandiose pause or ponderous music sting, no grand build up accompanied by an anticipatory drumroll. Just a blunt kick and an equally blunt “He did.” from the narrator.

Affronted expressions on the receiver evoke momentary sympathy from the audience.

The animation in Avery’s cartoons has seldom met the amount of prolonged elasticity gloriously displayed in this next sequence of one Palookavich rushing to make a touchdown and literally getting dogpiled. Contortions and pure caricature of rubber physics are most obviously concentrated at the beginning, primarily from the impact of catching the ball and the rapid, vigorous run cycle down the field, but even the opposing teammates tout their own plasticity that is especially firm and confident in its construction.

Such tactile motion was typically reserved for fleeting moments or wild takes in Avery’s world—to see it so prolonged and so confidently at that again yields great growth in his career. While his story ideas have petered out in the past year or so, focusing primarily on spot gag and travelogue shorts, the draftsmanship has been on a steady rise. So much plasticity hasn’t been seen since the days of Irv Spence being in his unit.

Filmmaking decisions such as a subtle truck-in and back out from the camera on the dogpile succeed in their attempts to immerse the audience in the action, the viewer drowning in the sea of heads, arms, limbs, and bodies. Moreover, the camera movement provides an added bounce of its own, almost disorienting the viewer in a sea of constantly moving plasticity.

Though Frank Tashlin had beaten Avery to the punch in Porky’s Road Race with the same gag of the medics retrieving the wrong center of focus, it’s still politely amusing in its delivery; dutiful woodblock accompaniment and a mischievous dirge of “Funeral March” provide what is now considered routine business with added playfulness and charm.

Further Thorsonisms in the designs make themselves more apparent as the audience is introduced to Gregory, a lookalike to the eponymous Dangerous Dan McFoo—puny, unassuming demeanor and all. Mel Blanc orates as a hollow-jowled coach, aforementioned mannerisms heartily reflected in his pep talk. Stoic music from Stalling slather a layer of wonderful disingenuousness on top of the tone.

“Al-l-l-l-r-r-right, Gr-r-regory…” Already, the coach’s demeanor is too explosive for the puny sap—his helmet is shoved in his face from the force of the jostles and further asserts his incompetence.

“You been on the bench for twelve years. He-e-e-er-r-res your big chance!”

Head shakes and jowl flaps are copious as the coach utters those magic words: “No-o-o-o-o-w get in there and FIGHT!”

Gregory is rejuvenated by the pep talk. We already know that he’s dead meat just by the nerdy run in place he engages in before rushing into the field, but it’s still a nice sentiment.

That the coach’s reactions are just as caricature and streamlined as Gregory’s pummeling deserves not to be overlooked and instead unifies the two actions greatly. Details of the beating are left to the rapid reactions of the coach, hardly any inbetween drawings enhancing the rapidity and spontaneity of his movement, the horrific metallic crash sound effects from Treg Brown, and, most importantly, the audiences imagination.

Pacing and brusqueness of the entire sequence provide a worthy predecessor to the timing in Avery’s MGM efforts, particularly when a body cast bound Gregory slams back into the wall and slumps on the bench. Zero in-between drawings, zero follow through—the lack of stretch and squash physics strengthens the gag and makes it feel more raw.

The sincerity in which the coach congratulates Gregory is wonderfully insincere in its delivery. A doleful stare from beneath the bandages seem to acknowledge this.

Back to the baby and the hungry dog, who receive no introduction from the narrator. We are well acquainted with the shtick—pensive, infantile glances from the baby are shared between the man and his ice cream cone. The caution in which he eats his dessert conveys that the crawling suspicion will reach a boil by the end of the cartoon.

Quick, polite gags such as a periscope poking briefly out of a huddle are employed to keep the momentum rolling.

Claims by the narrator of the quarterback barking out his plays are taken literally. It’s one of the gags in the picture that is somewhat more by the books and doesn’t exactly possess the same celebratory shamelessness, but the ferocity of Blanc’s barks intertwined with his orders are spirited and inspired.

Cut to an aerial shot of the players hopping aimlessly in tandem with the QB’s rapid “Hike! Hike hike hike! Hike! Hike!”s.

“Papovich gets the ball and fades back for a long pass… he’s fading… he’s fading… he’s fading…! He’s fading…!”

That the football itself doesn’t fade along with Papovich is yet another literal depiction of the narrator’s claims ground the scene and, once more, makes it feel more absurd in the process. Rather than both fading together, the perfectly opaque football reminds the audience of its holder’s presence and offers a strong means of comparison between visibility.

Stalling’s orchestrations of “Frat” shift to a new verse in conjunction with an accompanying change in energy. With the football bouncing off of a particularly rotund player’s stomach, the fumble, as deemed by the narrator, provides a vehicle for the next gag: the pigskin.

Grotesque pig squealing sounds are certainly foundational for the illusion, but the real strength of the joke is the weight and freneticism in which the football writhes and struggles in the arms of its possessor. Similar praises apply as it rushes down the field like a wild hog on the loose.

A rather gratuitous crowd shot indicates that the audience is overjoyed at the spectacle rather than terrified. No questions are asked nor needed.

Adjacent to the rapid brawl that occurred during the coin toss or the unabashedly elastic dogpile, pure spontaneity and absolute caricature of action render the next scene of the two teams slamming into each other a complete delight. Abruptness of movement and strategically ear shattering sound design again provide a worthy fore-bearer to the humor that would dominate Avery’s filmography at MGM. Such chaos requires a great amount of planning and understanding of which beats hit the hardest and how. Breathless narration wondering whether it’s a touchdown or not adds further strength.

“Did they make it? Is it a touchdown? Is it!?”

A cartoon produced by Warner Bros in 1939 almost always secures a radio catchphrase, this time pooling the wisdom of Mr. Kitzel from The Al Pearce Show: “Mmmmm… could be!”

“And there’s the gun that ends the half!”

The referee raising his gun in tandem to the ticks on his watch not only furthers the harmony between the two actions, but makes the gun a visual focus rather than the clock. Even then, the watch cavorting up and down on his wrist with each tick provides a solid visual signifier. Raising of the gun (especially to his head) is a bolder focus, but the jumping clock ties the ticking arm movements together. Such a rhythmic balance may be lost if the clock ticking wasn’t reflected in the animation.

Suicide gags and those adjacent would soon grow to be commonplace. Despite the grand buildup to the ref pointing the gun at his head, the blast itself still comes as a surprise thanks to the sound effects and brazenness of the joke as a whole. Likewise with his head entirely missing. The clock still ticking on his watch follows the same philosophy of the visible football held by the fading player, a reminder of what was once there before.

Moreover, the dopey grin as the dog pops his fully intact head back up from the safety of his shirt provides a knowing concession as though from Avery himself, understanding the cruelty of the setup and delighted at having tricked the audience.

A signature Averyesque head twirl take somewhat disenfranchises itself from the sequence, impact slightly lost through an attempt to save face—ending on the dog’s smiling face and nothing more would have been a more confident, less apologetic route. Avery would learn to refine this soon.

“They change sides for the second half.”

Hues in the crowd vary slightly, much to the scene’s credit as the spectators switch stands in a giant mass exodus—one side has a slightly more blue tint, the other black, making it easier for the eye to process the switch.

Another visit paid to the man stealing the baby’s ice cream; this time, the baby eyes him before he can even take a lick. A scowl on the infant’s face solidifies the suspicion.

With halftimes come marching bands, and with marching bands come marching band gags. Avery’s opener of a trumpeter’s matryoshka of horns feels somewhat antiquated, a gag one would expect to see in the Harman and Ising days of Warner Bros cartoons. Thankfully, the benefit of modern (for 1939) knowledge, experience, and draftsmanship as a whole allow visuals such as the final horn turning flaccid to feel more impactful in its presentation.

The marching band gags are tame compared to the chaos thus far, but remain striking visually on all fronts—an impressive amount of control and looseness is exercised with a dry brush heavy sequence of a baton twirler getting spun around by the baton, and moving background perspective animation from both horizontal and vertical directions provide an impressive backdrop behind a dog pounding its gut like a drum.

Avery borrows from himself in the next gag of a cheerleader riling up the stands; the same climactic soft spoken-to-passionate-screaming crescendo was seen in his Johnny Smith and Poker-Huntas and would be reprised again in Big Heel-Watha at MGM. Here, the sequence has the benefit of Stalling’s climaxing music score matching the growing fervency in the cheerleader’s voice—Blanc hits it out of the park as always.

“GIVE IT EVERYTHING YOU’VE GOT! YEEEEEEEEEEELL!”

“Rah. Rah. Rah.” Isolation is shared between both the music—or lack thereof—and the lone spectator’s surroundings.

“In the dressing room, the players and coach get together for a pep talk.”

In a classic Avery reversal, the players are the ones berating the coach and shouting the “YOU OUGHTA KNOW BETTER THAN”s—the helplessness on the coach is priceless, and the one player in particular jostling is a visual delight thanks to its rapid simplicity. A cycle of three drawings, two of them key poses, all held for one frame for maximum violence.

Even then, no punches are held—quite literally, as the players go so far as to deck the poor coach between intermittent jostles.

Back again to the baby and the theft. Modes of ice cream thievery strategically grow more absurd with each and every check-in. Not only does it allude to a boiling point, slowly growing more imminent as the cartoon has less than two minutes of runtime, but it keeps the audience engaged and focused on what to expect next. Both the methods of stealing (tapping the baby in the shoulder) and reactions (baby growing visibly more perturbed) continue to be exaggerated.

“And the referee blows his whistle to start the second half!”

Having the whistle swell up like a balloon and release through the air isn’t one of the most inspired gags offered by the picture, but the solidity of the whistle and perspective animation in which it glides is appealing visually.

Time for the kickoff—another aerial shot of the players assuming their positions bridges the scenes together and provides the audience with a brief taste of more “serious” matters…

A kick causing the football holder to fly across the screen, ball in arms is a fitting response to the earlier gag of the kicker punting his teammate over the ball. Of course, this in itself is more of a segue into a more extreme joke rather than a point of humor itself, and Avery knows this.

Stalling’s accompaniment of “The Kiss Waltz” provides its own commentary as the holder gives a bashful kiss to the receiver; interesting how same sex kisses being played for laughs seems to—at least for WB—start and be notarized by Avery; it was first seen in Cinderella Meets Fella, and of course would soon grow synonymous with Bugs Bunny’s means of heckling starting as early as A Wild Hare (or even Prest-O Change-O and Hare-um Scare-um, accounting for the prototype.)

Receiver is not pleased by the advances, but the holder remains unfazed. In a display of sportsmanlike conduct, he goes as far as to hand his opponent the ball.

The receiver is appropriately dubbed “Scramovitch” as the narrator breathlessly comments on his advances down the field. Strong construction, rhythm, and momentum guide his run cycle that again assert great strides in solidity poured into the draftsmanship and animation—even if one does at times yearn for the free-for-all looseness of Irv Spence’s work.

On the topic of Spence, a radio commercial interrupting the commentary and completely halting the flow of the game pulls from A Feud There Was, which had an excessive Spence influence in its designs. A bit of Thugs with Dirty Mugs is also channeled in the way Scramovitch lies on the field, infantile in his leg swinging and coy posing like that of a child enraptured with the ever thrilling radio waves. Coy narration and advertising products as a whole (“This program is coming to you through the courtesy of the Corny brand Fluffies Breakfast Food Company,”) further the saccharinity and tonal whiplash.

Interruption or no interruption, the receiver scores the touchdown courtesy of some physics-bending visuals that call to mind the days of inkblot and early rubber hose cartoons in their casual manipulation of their surroundings.

“The cheerleader is yelling his head off!”

Blanc’s guttural, ear-splitting hysterics are given the visual bonus of a literal translation; tangible plasticity of the motions and the variations between head and body physics enable the joviality of the scene.

While many directors have attempted to channel the Frank Tashlinesque montage (inter-spliced pieces of footage laid on top of one another to convey the passage of time), few have managed to capture the sincerity of the device. Avery thankfully is an exception, as every piece in the montage is new animation rather than reused clips aimlessly cobbled together to fill time.

It does absolutely read slightly as a way to pad time and seek closure rather than a wholly cinematographic move and nothing more, but the varied camera registers and actions are nice; purposefully senseless violence à la the Three Stooges is mixed with perspective shots of the players running towards the camera or across the field, providing a solid balance overall.

In spite of the histrionics viewed thus far, the score is only tied at a puny 7-7 at the end of the fourth quarter—a more subtle approach to Avery’s absurdist ways.

A quick return to the baby and it’s thief quells the audience’s nerves. A resolution is surely brewing.

Players line up in their positions, the ball holding the answers and prayers to both audiences animated and real alike…

Only to be interrupted by the crack of a gun. “And there goes the gun that ends the game!”

Said gun ends a life in addition to the game. Suicide gags would be prevalent in the coming years, but it’s particularly rare for characters to shoot other characters fatally (or, in the case of Hare Ribbin’, have Bugs fatally shooting a dog be changed to the more “family friendly” assisted suicide approach of Bugs supplying the dog with a gun to do the honors instead.) Especially infants, for that matter.

The trail of smoke still snaking out of the pistol adds further insult to literal injury, calling attention to the consequences of the action and reminding the audience this was a fresh kill. Stalling’s grandiose, almost mournful orchestrations of “Rock-a-Bye Baby” provide further sardonic gravity to the situation.

Both the half lidded eyes on the infant’s mournful glance towards his ice cream and the thick eye lines on his blinks possibly suggest the animated work of Bobe Cannon—the baby does seem particularly reminiscent of Cannon’s animation for Pinky in shorts such as Porky’s Naughty Nephew and Porky’s Picnic. If nothing else, it would certainly explain the attractiveness of the drawings, subtle acting decisions such as the brief glance towards the ice cream, and appealing motion as a whole.

Satisfied expressions on the baby as he licks the remainder of his ice cream signify that it was all worth it in the end.

Screwball Football is a short that stands out much more for its presentation and delivery rather than the substance of the gags themselves. Even then, like most of Avery’s cartoons, the jokes themselves tend to lack a self congratulatory attitude, which makes them easier to digest and more endearing. Instead, much of Football’s appeal comes from its raucousness, whether it be through raw speed, frenetic animation, or the ending.

Looseness inherent in the premise supports the lax, playful tone of the short; this is not another travelogue in which Robert C. Bruce lectures us on the peculiar splendor of nature’s bounty. Instead, it’s a good ol’ fashioned rousing game of football; clichés of both the spot-gag format and sports gag as a whole are ripe to be warped. Avery’s refined sense of speed provides a worthy predecessor to his MGM cartoons—much like the the majority of Dangerous Dan McFoo, scenes such as Gregory spending more time preparing for his time in the game than actually playing in it or the one football player recklessly jostling his coach in the locker room feel like gags or deliveries that would be commonplace at Metro.

A reliance on shock humor, particularly that involving guns, sets another precedent for the coming years. Perhaps the buildup of every suicide gag or brutal maiming wouldn’t follow the same meticulousness as both examples here (especially the continuity with the baby), which works both to a detriment and a success given the circumstances, but a shift in tone is absolutely there. A tone that would soon become the norm.

While Football may not have the tightness nor structure of cartoons like Land of the Midnight Fun, its lax premise and establishment from the start do not demand such rigidity in format. Sports do not demand an engaging storyline nor excruciating displays of cinematic excellence. Instead, they require energy—energy, spirit, and mischief. Football exceeds in all three.

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment