Release Date: December 2nd, 1939

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Chuck Jones

Story: Rich Hogan

Animation: Bob McKimson

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Margaret Hill-Talbot (Sniffles), Mel Blanc (Piper, Bookworm), Bill Days (Piper), Johnnie Davis (Little Boy Blue), The Sportsmen Quartet (Chorus)

(You may view the short here or on HBO Max!)

The third and final Sniffles cartoon of 1939 debuts his short-lived yet somewhat memorable sidekick: the bookworm. A literal take on the idiom, the bookworm is a small, green inchworm adorning studious spectacles, a bow tie, and gloves. While this short places a heavy emphasis on pantomime as a whole, the bookworm remains mute in all of his cartoons.

A de facto entry in the “books come to life” series, this one follows an interesting spin in which the books are more vessels for their characters rather than strict, thematic bondage—they are free to move around as they please without worrying about sticking to the themes of their books too closely.

Here, the little bookworm spots Sniffles, mistaking him for a giant monster, and is quick to warn the denizens of the bookstore. However, after a brief misunderstanding, Sniffles is transformed into a hero as he takes on Frankenstein’s monster looking to stir up trouble.

Not unlike most shorts of the genre, Bookworm begins through a series of idyllic establishing shots. An old fashioned bookstore covered in snow and illuminated by street lamps succinctly establish a quaint atmosphere—double for the footprints following the mouse hole in the wooden door, indicating Sniffles’ presence. That the footprints follow into the store’s interior is somewhat tedious, as the point has been proven through the previous shots, but nevertheless make the abode feel lived in and occupied. Note the book prominently labeled on the history of cartooning.

Transitions to Sniffles himself are somewhat jarring; the camera jumps directly to a shot of him dozing on a bookshelf. While that is fine in itself, the truck-in along with the jump cut adds an unnecessary jolt. It feels as though a cross dissolve was planned to precede the truck-in, which would have padded and smoothened the transition—even just performing a regular jump cut sans camera movement would have been fine. A small nitpick, but it does somewhat disturb the sleepy atmosphere through accidentally contradictory filmmaking.

Snow melting off of Sniffles’ hat and boots indicate that his refuge in the bookstore is recent. A few seconds too many are delegated to his dozing, as that has been established swiftly—a somewhat awkward pause persists before a bulge in the book behind him pushes its way through.

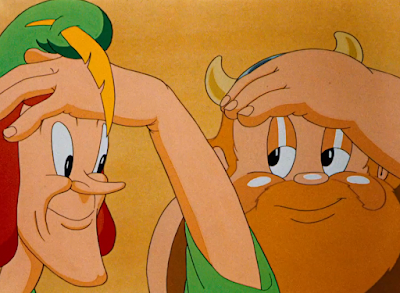

Enter the bookworm in all of his worm-y glory, sculpted construction and meticulous head tilts the unmistakable handiwork of Bob McKimson. Such solidity is touted in something as menial as the hole in which the worm has torn. Before he pokes his head out, the audience is provided a quick glimpse of the numerous pages from inside that have been torn. A new depth is added to the scene not exclusive to the characters, but the backgrounds and environments as well.

Upon spotting his rodent visitor, the bookworm grows startled and departs back in his hole. Such head grabbing takes are commonplace for the remaining half minute of the scene. His energy and fervor provides a nice contrast to the docility and contentedness of Sniffles, as well as supplying a natural guide for the audience’s eye. Giant takes require more attention than a sleep cycle.

Sniffles does eventually awaken—not from the presence of the worm, but the sound of his spectacles clattering against the shelf. His own take as he jolts awake is mild compared to the panic demonstrated by the bookworm.--as it should be.

In fact, he doesn’t even realize that he has company until he spots a gloved hand reaching aimlessly for the glasses. Following the pantomime routine that would soon dominate many a Bugs Bunny cartoon and those synonymous, the worm’s fingers land on Sniffles’ tail rather than his glasses.

To his credit, Sniffles’ reaction upon getting his tail pinched is politely cautious, curious rather than hurt or offended, which renders the action more lighthearted rather than potentially malicious or sympathy inducing. Like us, Sniffles seeks to learn more of this elusive fellow.

His silent wishes are granted as the worm takes the liberty of poking his head out of the hole. Had this short been made a few years down the line, the beat in which the two make pregnant eye contact almost certainly would have been preceded with a mutual slow creeping grin accented with a violin slide of sardonic disingenuousness.

Instead, thinking more in the 1939 Jones mindset, the worm exudes another face grabbing take of panic before taking a frantic exit again.

This time, glasses are included.

Jones and company do a fine job of conveying the worm’s panic purely through background environments. The camera pans away from Sniffles and follows an interminable line of books arranged on the shelf, all in tight proximity—the worm pops out at the end without missing a beat in the pan, hopping along the shelf to take care of some unknown urgency. Note the shoutout to background painter Art Loomer on one of the books; little inside references such as this will continue to pepper the remainder of the cartoon.

A shift placing a heavier emphasis on books and the contents therein are delivered through the worm’s anxious knocks on a novel.

Rather than the Pied Piper jumping off of a page and engaging in a spry, piping chorus, his book instead opens to reveal a hollow makeshift bed in which he rests, completely independent of his pages and their restrictions. The characters feel more dimensional, realized, and lifelike as a result—the book isn’t so much a heavy emphasis as it is a means of establishing the ensemble.

Pantomime has a stronghold on this cartoon, to both its success and detriment. The bookworm’s attempts to warn the comatose piper are slow and bloated, partially due to the piper’s languid movements as he awakens. A “Yeeeeeah?” after the lengthy silence attempts to jar a laugh out of the audience from the contrast—it reads as obligatory and forced more than humorous today.

McKimson’s close-up of the worm pantomiming Sniffles’ giant size, making him out to be a giant, worm-eating monster rather than a sleeping mouse is appealing and confident enough visually that it distracts from its lengthiness and redundancy. Excess wrinkles as he shrinks his head into his shoulders stress the dimensionality of his construction, as does the perspective of his arms reaching into the foreground. Carl Stalling’s frantic music score rising to a crescendo with each broad gesture further rescues the scene from utter monotony.

Or, at least, mostly—another “Yeah?” from the piper doesn’t strike the comedic tone it seeks.

Perspective on the piper marching towards the camera is solid. However, like everything else, the movement is too slow and liquid to confidently evoke the boldness that his determined footsteps demand.

Similar critiques follow in a horizontal pan of him marching along the bookshelf. To perhaps appear artsy and unconventional, his legs are completely out of frame. As such, his marching loses some of its impact—seeing as the weight goes to the feet, concealing that when the upper half of his body doesn’t exactly convey the same leaden weight makes him feel ambiguous, floaty. Likewise, the staging seems to hint towards a surprise that never comes. One expects the camera to truck-out or reveal to a gag involving his legs given the specific decision to excise legs as a whole—such is not the case.

Nevertheless, footsteps halt as he turns back to the bookworm for further validation. Bookworm confirms the size of the terrible beast is much bigger than the piper is anticipating. Visually appealing, yes—silhouettes and line of action are particularly poignant on the piper, and that so much unspoken dialogue is conveyed through mere gestures is certainly by no means unimpressive. Tedium still nevertheless blankets the entire sequence—bloated timing, repetitive acting, and (at least in the piper’s case at this point in time) characters who aren’t incredibly endearing to begin with.

All of the above apply with the uncomfortably intimate close-up shot of the piper smacking a hand to his face in petrified realization.

Wrinkles that would make Rod Scribner green with envy adorn the piper’s clothes as he takes off into a sprint, hair flowing freely behind him. Much of the weight in the animation feels aimless in its floatiness rather than anchored. Regardless, the acknowledgment of such physics are immersive and certainly do make an impact.

Cautious whispers shed into another book-domicile prompt the arrival of a hulking Viking, contrast palpable between the body types of the two humans. Model sheets for the cartoon label the Viking as Eric (with a c), a potential nod to Leif Erikson. Armed with a club, he lumbers offscreen—chronic languid pausing precedes the piper’s pursuit behind his buddy.

One of the cartoon’s strengths is its musicality. Or, more specifically, it’s musical theming; the Viking and piper are accompanied by a leaden, foreboding yet mischievous woodwind score. Frantic, staccato fifing follows the bookworm’s frantic slugs forward, fitting both his puny size and anxious demeanor.

Unbeknownst to the parade, a guest lurks in the shadows; Sniffles observes gleefully from a crack in the books before joining the march himself. Economical staging is also a benefit wrought by this short—the eye of the viewer is rarely misguided and compositions are strategically arranged for maximum clarity. Solid awareness of negative and positive space further embolden certain pieces of staging.

Sniffles’ vacantly cheerful expression as he struts along with his hands in his pockets is nothing short of appealing. Charming, endearing, oblivious to the fact that the shushes all shared between the Viking, piper, and bookworm are directed towards his presence. No “Whatcha doin’?” or any sort of confusion as to what is unfolding—he just hops along right for the ride. Such is a sincere, cute, and admirable quality.

More double takes emit from the bookworm after realizing he’s shushed the enemy himself; great line of action and arcing on his body as he smushes his face right up to Sniffles in a move that is pure Jones.

Another terrified beat for good measure, another exit.

In a moment of catharsis, Jones touts a refreshing burst of speed so absent in the cartoon as the bookworm bowls his companions over in a panic. Animating the impact on ones—as well as the addition of dry brush—perfectly caricature the speed in which he’s moving.

Likewise, it is somewhat difficult to fully comprehend given the promptness in which it occurs, but the piper rides the Viking like a horse offscreen as they too make an equally panic stricken exit.

Instead of delegating a beat to a nonplussed reaction from Sniffles (which would evoke and prioritize empathy, personality acting), comedy and momentum is further prioritized as the camera cuts straight to the gang hiding behind some books. Note the Porky Pig cameo by name in the background—one of two for the short.

Talks of economical staging mentioned prior reach their zenith in this next scene. With the camera settling on a slight point of view shot from the bookworm and company, books in the foreground frame a pleasant, somewhat confused but contented Sniffles. Discrepancy between the opaque black books and the color in the remaining environments allow the contrast to read all the more boldly, naturally guiding the eye to Sniffles’ appearance.

Moreover, in an intriguing twist, a silhouette shot of the two book dwellers and bookworm reads more as a “shadow shot”, should there be such a thing; all three are colored so that some of their features are still visible, sculpted only by vague, black shadows to give them further definition and depth.

All three faces are strong in their differentiated silhouettes, immediately recognizable. Likewise, they all maintain a visible frame around Sniffles and sustain clarity despite the purposefully cluttered composition. Adjoining musical stings for each head that pokes out from behind enable further unity.

Thus cues the ever imminent confrontation between bookworm and book dwellers. Belabored as the silent confrontation is, pantomime still in full force with the bookworm, the contrast in character designs, posing, and demeanor is certainly effective.

Both the Viking and piper loom over the puny bookworm, making his dwindling arguments against Sniffles’ size as big as his own height—that is to say, not very. Moreover, the line of action on the piper curves outward whereas the Viking curves inward, invoking a natural discrepancy between the two but uniting them between shared emotions. The barrel chest of the Viking births a clear frame over the bookworm, especially when he shrinks into himself.

Adjoining shots of the piper and Viking wiping their brows is awkward for multiple reasons. The most glaring is a lack of hook-ups between scenes—in the close-up, the Viking is practically shoulder to shoulder with the piper. Conversely, he is completely absent in the shot afterwards.

While it’s to promote visual clarity and accommodate the grand gestures of the coming scene (which is where part two of the awkwardness settles—the piper wiping his brow is actually used as a transition into summoning a clarinet out of thin air. This one is easier to pardon, as it’s an artistic liberty and one that is fantastical and unconventional, but still somewhat jarring in its execution, especially given the unbroken eye contact between the piper and the audience), having the Viking exit out of frame in the close-up or attempt to squeeze him into frame in the wide shot would have allowed the bridge between scenes to flow more smoothly. Instead, the result is abrupt and bumpy.

A musical number dominates the next two and a half minutes of the cartoon. While that almost sounds painful given the vague description, it’s actually quite the opposite—jaunty, spirited, endearing, and most of all catchy, the sequence births a spunk desperately needed.

Depicting the piper as this fantastical being who can summon pipes with the wave of a hand (as is demonstrated not only with himself, but by gifting Sniffles his own miniature pipe in an act of sincere, almost familial solidarity, indicating that Sniffles is one of his own now) is as fascinating and even enrapturing as it is puzzling. Harmonized clarinet solos between the piper and Sniffles upholds a cute sense of unity and newfound friendship. Very cutesy to the degree that some may find it cloying—and it is—but the tangible joy and warmth that radiating from the gestures grant a pardon.

Bill Days of the Sportsmen Quartet provides the piper’s singing voice, whereas actor and singer Johnnie Davis (who provided the vocals for Johnny in Katnip Kollege) supplies the vocals for Little Boy Blue as we segue into a rousing number of “Mutiny in the Nursery.”

Appropriate for both the story’s setting and the song as a whole, the number follows a theme of nursery rhymes; mother goose and her eponymous water fowl dance, a trio of Little Bo Peep(s) provide their respective harmonies, the pied piper gets his own solo.

Ironically, the most interesting portion of the song number may very well be the cameos and inside jokes in the background. Porky’s face is prominently displayed on a line of books behind Mother Goose (somewhat anachronistic in design, as the rounder, more even face and hat evoke the 1937 model more than the late 1939 appearance), Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies receive a shoutout, and Chuck Jones himself is referenced in a book entitled “Jones Anatomy”, the author billed as Leon Schlesinger. Likewise, Dave Monahan, Rich Hogan and Bob Givens are all referenced through their surnames towards the very end of the sequence.

Of course, outside of a historical animation perspective, the main component catching the audience’s eye is the Frankenstein’s monster lumbering towards the festivities. Surroundings of the monster are fitting, as his book is old, decrepit, colored a purposefully unappealing gray as it’s shoved into a dark corner laden with cobwebs and even a skull.

Intriguing is the monster’s coloring—his green association stems much from the technicalities of working in black and white. Boris Karloff was painted in green makeup for the 1931 film as it appeared best in black and white—even then, posters for 1935’s Bride of Frankenstein depict him as a yellow-green color. After all, this short does only take place 8 years after the Karloff film, which is quite recent. Frank Tashlin’s Have You Got Any Castles? also depicted him as beige a year prior.

None of this is a complaint so much as it is intriguing from a historical and pop culture standpoint. The green coloring has been so engrained in modern preconceptions of the character that it’s fascinating to view other alternatives, especially so early on. After all, the first in-color Frankenstein movie wasn’t released until 1957’s The Curse of Frankenstein, and even then he’s a sickly white rather than green.

If there are any complaints to be had, it’s the confusion behind the monster’s construction—his build and movement as a whole feel incredibly mechanical, robotic rather than reanimated. A stylized interpretation for certain, it inadvertently detracts from the threat he poses; he appears like a giant, lumbering robotic toy left by a kid rather than a monster armed with the intent to kill. Frequent cutting back and forth between the musical number and his arrival attempt to increase the stakes of his appearance.

The song number approaches its finale through a chain of events: the Viking (whose nose is erroneously inked black) playing a cello immediately deserts his post upon spotting the monster. A momentary trumpet solo from the piper (instruments swapped so Sniffles could have the clarinet solo?) is cut off for the same reason, as is Sniffles’ and the bookworm’s. Unlike the Viking and piper, both the bookworm and Sniffles remain cemented in their respective places. For the bookworm, it’s an act of petrifaction.

A perspective shot of the monster looming over the bookworm is interrupted by Sniffles yelling “STOP!”

An attempt to mimic the crashing halt seen in The Night Watchman under very similar circumstances falls somewhat flat. In Watchman, Tommy Cat screams at the rat mobsters to stop their jazz playing in a moment of vulnerability. He, much like Sniffles does here, immediately smacks a hand to his mouth, preparing for the consequences. Unlike the monster, the rats have established themselves as a threat for much longer and have beaten up on Tommy prior to his outburst.

Any threat from the monster here is superficial at best—we are meant to be afraid of him purely because he is Frankenstein’s monster, and Frankenstein’s monster is scary by association. However, in the context of the cartoon, he hasn’t given the audience much reason to evoke fear or suspense.

Overcome by the excitement, the poor bookworm passes out as Sniffles is now left to his own devices in fighting the monster. Whether it be the shadows carefully sculpted on the bookworm or the shadow of the monster itself looming over Sniffles, the added shading does certainly stress some much needed severity in the situation. The same could be said for repeated cutting back and forth between Sniffles and his adversary—Leon Schlesinger and Henry Binder are given additional acknowledgements in the background.

Like much of the cartoon as a whole, the rise and literal fall of the monster is very anti-climactic; Sniffles takes him down by hiding on the edge of the bookshelf and tripping him with his foot. Layouts of the bookshelves and books themselves are certainly impressive—upward angles exaggerate the height of the monster and the bookshelf as a whole, as well as add a slightly warped feeling of anxiety due to the sharp, tilted angles. Relationships between negative and positive space are keenly acknowledged and utilized to their advantage, making for clear and comprehensive staging.

However, the altercations feel forced and obligatory; Frankenstein’s monster is purely a story device and nothing more. While that could be said with every villain that appears in every story, his appearance here reads superficially and provides very little worthwhile threat. Much of that may boil down to the primitive, confusing design intertwined in a battle between robot or monster. Any anxiety or tenseness is conveyed purely through environments and filmmaking maneuvers rather than the actions of the characters themselves.

Still, with all of that said, the literal bookend at the end of the cartoon is a cute device. Identical to the opening, Sniffles assumes his position and falls back asleep after the taxing events prior. A familiar bulge burrows in the book behind him…

Animation of the bookworm looking around is repeated in a consistent parallel.

Instead of growing startled at his company, he is now grateful—a kiss of thanks is planted on Sniffles’ cheek before making his departure. The heart smacking effects are cloying yet playful.

And, just as before, the worm leaves his glasses behind, giving Sniffles an immediate idea behind the culprit. We iris out on his contented, knowing grin to the audience.

Sniffles and the Bookworm is a succinct demonstration of how, in spite of strong or attractive visuals, a short can flounder without a solid foundation. While easily one of Jones’ weakest entries yet, it isn’t actively terrible by any means. There are no beats, decisions, or aspects that are actively egregious—just devoid of substance.

Indeed, to sum up the cartoon in one word, it would be “insubstantial”. Its visuals are solid—very atmospheric, a clear level of attention devoted to shadows and highlights, and sculpted animation from Bob McKimson works in favor of Jones’ quest for rounded, Disneyesque visuals. Likewise, the music is especially catchy and contagious. Pantomime is clear in its intent and delivery, even if so much of it is riddled with awkward pauses or repetition.

However, this cartoon is bloated, circuitous, and obligatory from a story standpoint. A bookworm sees Sniffles and gets scared. Bookworm warns piper about Sniffles. Piper gets scared and warns Viking. All three seek out Sniffles. Sniffles is a mouse. The coast is clear. Segue into a musical number as celebration. Frankenstein’s monster approaches and disrupts the celebration. Piper, Viking, and bookworm are all too incompetent or compromised to fight back. Sniffles trips monster. Sniffles goes to sleep. Bookworm kisses Sniffles. The end.

While this short has some of the most molasses timing out of any Jones cartoon yet, much of that feels purposeful. It's as if Jones himself knew the story couldn’t hold itself up on two legs, hoping to distract by padding out the time through pregnant pauses and repetitive actions.

This isn’t so much a case of amateurism or struggling to understand the craft—Jones receives a lot of flack for how slow or domestic his shorts were in the first few years, but his growth from 1938 to 1939 alone has been quite substantial. Comparing the visual and directorial quality of this to The Night Watchman yields great growth—it’s just the story and a complete lack of sustenance that render it a whole lot of nothing. Perhaps “a whole lot of fluff” is a more accurate deduction.

Nevertheless, both Sniffles and his bookworm friend have more chances to shine. In the bookworm's remaining two appearances, The Egg Collector, much like Little Brother Rat, is gorgeously cinematic and much more fulfilling in its story. Likewise, Toy Trouble politely scratches the itch for comedy and boasts an upbeat attitude that isn’t just for decoration.

Much of the disappointment from this cartoon stems from knowing Jones was capable of more fulfilling ventures at the time—from a 1939 standpoint, it politely accomplishes its mission. That the song number dominates much of the cartoon makes it feel akin to the earliest Looney Tunes shorts with Bosko, 7 minutes of music, dancing, singing and nothing else. Very Depression-era in which one seeks the theaters for an escape, any sort of relief brought on by jovial, smiling characters and antics. If that is the case, this serves that niche well, but Warners as a whole has attempted and proven to have disassociated itself from such a mindset. Or, at least, moved on from the barebones structure.

No comments:

Post a Comment