Release Date: November 18th, 1939

Series: Merrie Melodies

Director: Ben Hardaway, Cal Dalton

Story: Jack Miller

Animation: Rod Scribner

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Tedd Pierce (Fagin), Jackie Morrison (Blackie), Margaret Hill-Talbot (Cat), Mel Blanc (Pianist, Hogan, Blackie), Sportsmen Quartet (Chorus)

(You may view the cartoon for yourself here!)

Whereas imitating Disney at Warner Bros in the year of 1939 tends to weaken a cartoon rather than strengthen it, Fagin’s Freshman draws a number of similarities to 1935’s The Robber Kitten and, by some miracle, is one of their strongest outings yet—perhaps stronger than even the source material.

Unfortunately, little is reliably known of the voice cast—Mel Blanc only lends his voice to a handful of incidental characters (and the star at the end in a quick attempt to shoo in some lines.) Voice expert Keith Scott suspects Tedd Pierce as the voice artist behind Fagin in an impression of Lionel Stander, the Sportsmen Quartet are always an easy guess, and the mama cat does sound like one of the regulars (Sara Berner?), but very little else is certifiable. IMDB lists child actor Bobby Winckler as the voice behind Blackie (who is also attributed to I Wanna Be a Sailor’s Peter Parrot), but, knowing IMDB, should be taken with copious grains of salt. Voice credits as such align more with unsteady guesses rather than cold, hard, fact—such is the nature of 82+ year old cartoons.

Pontificating aside, Fagin’s Freshman follows a refreshingly solid storyline. Annoyed with the childish, goody-goody antics of his family, little Ambrose (alias “Blackie”) seems to dream of more interesting endeavors such as gunfights and mobsters. A hulking cat by the name of Fagin takes him under his wing and offers to teach him the ways of being a criminal, but when said practice is put into a real scenario, Blackie is eager to embrace the cloying saccharinity of his old life.

For a cartoon who intends to lure the audience into false saccharinity in its opening, it succeeds at its mission almost too well. Exceedingly Disneyesque in its cloying arrangement, a family of cats all gather around the piano and sing a chorus of “The Three Little Kittens”. Gil Turner animates the opening, whereas Dick Bickenbach assumes duties on a close-up of mama cat singing back to her little ones. Turner’s animation isn’t riddled with terminal floatiness, which is a plus, and Bickenbach’s close-up boasts an impressive solidity.

A shot of a lone kitten scowling in the corner arms the audience with wry reassurance—this song number is supposed to be horribly sickening. Almost immediately, the viewer is meant to sympathize with the disgusted glances shorn by the kitten; he is meant to reflect our own thoughts at such trivial matters. Likewise, the saccharinity of the number being so strong aids in emphasizing the kitten’s disgruntlement.

As such, the radio is employed as a means of distraction. Mama’s chorus is quickly interrupted with a cacophony of explosions and gunshots —an added air of suspense manifests through quick cutting back to mama. We barely see the kitten’s delighted reaction before resuming back to the rest; the gunshots and noise from the radio seem more surprising, abrupt, and disruptive as a result. Having the kittens immediately take shelter from the presumed gunfire rather than recognizing it as mere radio fodder further bitters the tone.

Staging the composition so that mama cat looms over her kitten when shutting the radio off establishes a solid hierarchy of power. Likewise, concealing her head and presumably disgruntled expression offscreen almost makes her seem more commanding, again sustaining that tangible suspense of the unknown-but-presumed. The audience knows she isn’t pleased, but aren’t aware of the exact extent to which her anger stretches.

Grabbing the cat by the ear provides a solid inclination.

The little kitten is thusly dragged to his room dinner-less. While some of the movement of the kitten struggling feels aimless, floaty, a tad slow when heading up the stairs, the diagonal staging is impressive for Hardaway and Dalton’s standards. Having the cats climb the stairs in the foreground feels as though they’re walking right past the audience, further immersing them into the picture.

Mama’s lecture of “All you think about is guns and shooting!” hints at the remainder of the cartoon. Somewhere, somehow, the kitten is going to get entangled with dreams of gunslingers.

Surprisingly, Hardaway and Dalton channel a bit of Tex Avery—and to their success—after mama shoos her little one into his room. With nary a protest from her son, she closes the door…

“And none of that backtalk, either!” The spontaneity in which it is executed is somewhat foreign to the lugubrious timing sense of remaining H/D efforts. A breath of fresh air, indeed. Mama closes the door in a newfound sense of finality.

With that, we segue to the punished kitten sulking in his bed, complaining about how he never gets to do “nuthin’.” As to be expected given the territory, his monologuing runs a little too long—an echo of “That’s kindergarten stuff!” following a sardonic chorus of “The Three Little Kittens” comes off as particularly unnecessary due to similar complaints (“That’s sissy stuff!”) a minute before. Nevertheless, his disdain is exceedingly clear.

Transitions to the next act of the cartoon read as somewhat forced; as many cartoons do, much of the plot unfolds in the context of the kitten’s dream after going to sleep—the transition between awake and asleep reads as particularly abrupt, a shift to a much more docile and pleasant tone touting a very manufactured delivery.

Thankfully, the transition between reality to dreamscape is much more smooth. The kitten’s consciousness shot on a double exposure exits the bed and sulks around in his bedroom—backgrounds dissolve smoothly from the bedroom interior to city streets without a single jump in the animation. Carl Stalling’s string accompaniment to note the kitten’s laden footsteps perfectly accents the backing track of “Deep in a Dream”, bestowing a pluckier, more determined finish to an otherwise gentle and domestic music score.

Likewise, that the setting established is a rundown area of town ties back to mama’s scolding and the cat’s interests as a whole—as someone who fantasizes about guns and mobsters and violence, it’s only fair that he would dream of surroundings synonymous to such a scenario in radio plays.

Much like Hobo Gadget Band, further exposition is established through the convenience of a sign, prompting a bloated shot of the character reading said sign. In this case, it’s never established what the boy is wanted for. Taglines touting no experience necessary is enough to hook our lead—surely it’s for something interesting.

Indeed, knocks on a nearby door warrant a response. In an attempt to subvert the ol’ “suspicious eyes glance through slide in the door” cliché, the door touts two openings to account for smaller heights. Not exactly pressed about concealing the identity of the stranger, seeing as his entire face is visible through the crack, a hulking cat on the other side peers through the top slide, shuts it, then peers through a bottom slide before granting his guest access. It would have been somewhat nice to conceal more of the stranger’s physical appearance and maintain some semblance of suspense, but given that the atmosphere is headed for a more hopeful, plucky direction with the music, such suspenseful maneuvers would be out of place.

Pacing dialogue has never been a strength in the Hardaway and Dalton cartoons. A somewhat bloated pause succeeds the kitten’s “I saw your sign there, and…” before the other cat speaks—the kitten trailing off loses its naturalistic intent and instead feels canned with the pause in mind.

Regardless, the cat allows his visitor inside with little trouble. It is then that the tone grows more foreboding, reflected in a mournful dirge of “Melancholy Mood”.

“Fagin’s my name. What’s yours?” Though the movement itself feels slightly artificial, Fagin’s posing in itself is strong, particularly when he extends his hand out. Clean silhouette, consistent line of action, solid arc.

If there were any suspicions of Disney’s influence, the kitten introducing himself as Ambrose Wilbur Scat—(“But the kids all call me Blackie,”) clinches it; Ambrose was the name of the title character in The Robber Kitten, who also happened to be a black [and white] kitten.

Fagin’s Freshman is a bit of an odd duck in the Hardaway and Dalton family of cartoons. Outside of having a relatively firmer and more fulfilling foundation than most, it successfully taps into an aspect so few other of their cartoons have been able to grasp wholly: endearment.

Fagin taking Blackie under his wing has been surprisingly positive—no grumbles to scram or get out, no quizzing on his whereabouts or how he got here. By a miracle of miracles, the characters actually feel somewhat sympathetic and genuinely intriguing outside of one dimensional personality traits or stereotypes. Even if Fagin is a bad influence, as all signs appear to point, there is a certain warmth in his mentorship that is completely lacking in much of the H/D filmography.

With that, Fagin introduces his apprentice to “da boys”: rough and tumble environments continue to establish themselves as said boys shoot dice and gamble in a makeshift classroom. An unintentional dinginess in the painting style and brushstrokes (a poor print of the cartoon may be to blame for further muddying the visuals) adds to the broken down atmosphere. Props such as the door, tables and various trinkets therein aren’t executed with a cohesive solidity in the paint style. Such vague looseness works with the purposefully cluttered and dank demeanor.

In spite of their gambling and carrying on, the kids clearly harness some form of respect for Fagin, as they immediately scatter in their seats upon his entry. Further elusiveness of his background and what sort of establishment he operates are noted through his commanding authority. Even if all of that does manifest in the form of a mere “Hey!”

Telltale blink lines give away Dick Bickenbach as the animator behind Fagin’s introduction of Blackie. Again, worth noting is the anomalousness of such a warmth exuded from Fagin—gestures such as holding Blackie’s hand or placing his own hand on his shoulder read as fatherly, endearing. He seems to take a genuine interest in Blackie’s company rather than belittling his puniness or plucky naïveté.

A resounding “Hi, Blackie,” from the class does not share the same warmth, but doesn’t exactly feel as shoehorned or one-note as other H/D endeavors do.

More lapses in dialogue pacing weasel their way into Fagin reassuring Blackie that going to school is necessary—not enough to be a major detriment, but enough to stiffen attempts at naturalistic dialogue.

A hall of “graduates” are displayed through means of various wanted posters. To the credit of Hardaway and Dalton, the villains and their aliases feel akin to that of a comic book. A logical deduction seeing as, again, this is a child’s dream who likely surrounds himself with stories of mobsters and villains.

Even a part of the Schlesinger staff is caricatured as a villain—a poster advertising “Cavett the Clutch” is a dig at Louie Cavett, described by peers as a card shark. References to Cavett can also be seen in Hardaway and Dalton’s Hare-um Scare-um.

Likewise, a poster for Fibber McKee is a much less subtle allusion to Fibber McGee and Molly. A reaction and recognition from the audience was surely guaranteed, especially by saving it for last.

“Ya mean ya… ya teach li’l boys ta be criminals?” Gil Turner animates Blackie’s concerns, immediately recognizable through the prominent teeth, angled head and uncanny evenness of the movement as a whole.

More unnecessary pregnant pauses follow as the camera settles back on Fagin and his apprentice; with Carl Stalling’s orchestrations in the background it’s much less noticeable, but thinking of the pacing in terms of natural conversation and sans accompaniment, it reads as awkward at best. Hobo Gadget Band touted similar issues.

Nevertheless, Fagin again attempts to calm Blackie’s nerves, claiming he’s only responsible for teaching the basics. Awkward as some of the voice direction may be, Tedd Pierce works an appropriate warmth into his deliveries that feels genuine. No matter the intentions of Fagin, his mentorship of Blackie feels fatherly and sympathetic. With how one dimensional and bland many of the Hardaway and Dalton characters are, such acting and personality, perhaps meager as it may be, is not to be taken for granted.

Courtesy of another floaty, melty close-up shot by Gil Turner, Fagin proposes the fellas rehearse their “theme song” to familiarize Blackie with the gist. Fagin’s features appear to move around and morph much more than Turner’s previous scenes—whether shoddy assistant work or otherwise, like most scenes it isn’t an active detriment (seeing as H/D cartoons aren’t typically renowned for their appealing drawing style to begin with) but does provide a weaker antithesis to the adjoining scenes.

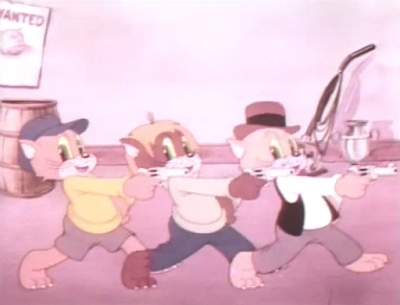

Enter one of Hardaway and Dalton’s stronger and more endearing song numbers: a child mobster-appropriate rendition of “We’re Working Our Way Through College”. It doesn’t feel like a spontaneous, last minute insertion as other H/D numbers do and is logical in its premise, demonstrating the ins and outs of their schooling—mugging dummies, loitering around fake street corners, robbing fake banks, locked up in fake jail cells. Infectiously catchy vocals courtesy of the Sportsmen Quartet are more than welcome and allow the number to feel more confident.

Likewise, the immaturity of the props doesn’t exactly feel as coy as it could, which is another benefit—backwards spelling and hastily made cityscapes ground the premise and deliver a naturalistic imperfection. After all, in spite of their open gun slinging and masculine singing voices, these are children.

The song’s end initiates the next act of the cartoon: being busted by the fuzz. Though the source of the knocking is only revealed through a close-up of their hand, audiences at this point have ingested enough cartoons to understand that the blue and gold striped sleeve is synonymous with a police presence.

Such is confirmed by Fagin’s peeking through the door slot (now back to only one as opposed to two.) Continuing to conceal the faces of the cops, plural, sustains the foreboding suspense, tapping into the weight of the unknown. Given the looseness of the animation and abundance of wrinkles particularly in Fagin’s clothes, Rod Scribner lends his handiwork to the animation.

“Are they REAL policemen?” Blackie’s momentary confusion between what is reality and what is a part of the schooling is another endearing touch.

How bizarre it is that one of the most frequent catchphrases ever to grace these Warner cartoons stems from a Hardaway and Dalton short. Future quips and punchlines pertaining to reasonable facsimiles owe a thank you to Fagin (or, more reasonably, writer Jack Miller), who responds with a brusque “Well, if dey ain’t, they’re a reasonable facsimile!”

As a somewhat unrelated note artistically, Fagin gesturing and looking over Blackie again touts confident posing and a particularly solid framing. Blackie appears all the more tiny and insignificant with his barrel chested mentor looming over him.

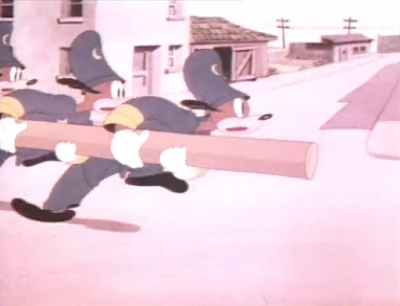

Having the cops all be dogs follows a solid line of logic—dogs are the natural antithesis of cats. Cops are the natural antithesis of mobsters. Thematically speaking, the conflict feels natural, structured, and consistent.

Much of the cartoon’s foundation softens in the scenes involving the police, but the dogs charging into the hideout with a batting ram is certainly not one of those occasions. Though the momentum itself could stand to be faster, the cops revving their feet like motors, the swerve into the foreground and gifting the scene depth and dimension, and the promptness in which they all fold onto one another like flat pieces of paper, only to spring back individually one by one all gift a plucky, playful energy that scratches an itch for slapstick surprisingly lacking thus far. Some more extreme sound effects could be used on the cops launching off of each other, conveyed only through slight woodblock clops and adjoining music stings, but the elasticity is felt in itself and doesn’t need to be carried through sound effects—a sign of success.

Lapses in the gunfight are most prominently demonstrated through one cop in particular. Showcasing the entirety of the gag at once would be just as taxing, but stretching out the fight so that the camera intermittently returns to a dopey dog cop shooting himself in the face with a pop gun and staring pitifully at the camera not once, not twice, but three times grows tiresome and childish.

Outside of Fagin quipping “Dat wasn’t done by no moth!” in a slightly redundant attempt at repeating the same structure of the reasonable facsimile line upon his hat getting shredded by bullets, the most inspired piece of the whole brawl comes from a phone call. Pacing predictably drags, but the promptness and obedience in which the coppers cease their shooting to allow Fagin time to answer is sharp and a pleasant subversion for Hardaway and Dalton.

Given the sheer amount of preparation for the phone call, one expects the phone call to perhaps be of mercy to Fagin and company. A tip-off? A distraction? Carl Stalling conveys the illusion of two-sided dialogue through a clever, imaginative flighty woodwind strain. Quite a creative liberty for H/D.

“Which one a’ you guys is Hogan?”

One of the dog officers cautions a “That’s me.”

“Ya wife says to bring home a pound a’ butter!”

Long as the sequence may be—criticisms of its length stemming primarily from knowledge that it could easily be slimmed down and work to the same effect—it, again, is a comparatively clever subversion for the likes of Hardaway and Dalton. No egregious “wah wah wah waaaah” music stings to rub it in the face of the audience, no befuddled blinks from Hogan and his adversaries. Just the fire of Fagin’s pistol.

Remainders of the gunfight delegate focus to Blackie desperately attempting to avoid the gunfire. Immediate comparisons are drawn to Porky’s synonymous gunfire escape in Porky the Gob—while Blackie still isn’t as intriguing as someone such as Fagin or the boys, he still carries a lot more sympathy than the former example, furthering the sense of urgency. It lacks the crudeness and unintentionally naïveté of the former, another successor, and the only bit of self indulgence that is paced quick enough to be rightfully amusing rather than unnecessary is a spray of bullets spelling “NO NO” in the doorway Blackie has targeted.

A return to reality is offered through a means of escape: getting entangled in a mass of curtains upon diving out an open window soon morphs into tangled bedsheets as Blackie finally wakes up. Dazed stars and effects are somewhat redundant upon his landing on the floor, a little too bloated and grandiose, but provide a fine transition to the finale of the cartoon.

In spite of his napping, jovial piano music can still be heard tinkling downstairs. Rather than scoffing at it, making a rejection to solidify his budding masculinity, Blackie is eager to enable such saccharine antics to show what a good boy he is—such is furthered not only through his chorus of “The Three Little Kittens” (clearly provided by Mel Blanc in a falsetto—perhaps they didn’t think to record the lines while they had the voice actor available?), but the raw speed in which he rushes down the stairs and into the living room.

Not only is the halo gloriously pompous in itself, the fact that Blackie feels the need to stick his head through the iris and bat his eyelashes truly cements a wry warmth that feels equal in its endearment and dry coyness.

Like Bars and Stripes Forever, Fagin’s Freshman is almost more bewildering than it is solid. That is, bewilderment stemming at HOW the solidity was achieved to begin with. Jack Miller wrote both cartoons (as well as Hobo Gadget Band, another H/D cartoon that lands harder on the tolerable side) and supplied strong shorts for Tex Avery such as Thugs with Dirty Mugs and Hamateur Night, so it seems logical to owe much of the short’s success to him. Indeed, the foundation feels more firm, confident, a solid bookend from start to finish that don’t leave the audience hanging in empty anticipation for more or confusion. Whereas portions of the gun fight drag (namely the dopey dog and generally elongated pacing), much of the short is consistent and coherent—an oddity for Hardaway and Dalton.

Signature Hardawayisms are certainly in the cartoon, particularly noted in poor dialogue pacing or gratuitous pacing as a whole, but gags don’t nearly feel as shoehorned or desperate to prove themselves. Much of that ties back to a solid storyline and a cartoon that places a heavy emphasis on story and characters—again, anomalous for Hardaway and Dalton. Like many cartoons of this era, it is best viewed when juxtaposed against previous H/D efforts in mind and understanding their style of directing as a whole. Not much attention is called on its own, but compared to the remainder of their filmography, it’s easily one of their most solid outings yet.

.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment