Release Date: November 18th, 1939

Series: Looney Tunes

Director: Ben Hardaway, Cal Dalton

Story: Tubby Millar

Animation: Gil Turner

Musical Direction: Carl Stalling

Starring: Mel Blanc (Porky, Knight), Billy Bletcher (Giant), Danny Webb (Baby)

(You may view the cartoon here or on HBO Max!)

A perfect demonstration of Hardawayesque cognitive dissonance, Porky the Giant Killer is a phenomenally confusing cartoon. Not so much vagueness in storylines, but delivery—it is easily one of their most layout conscious efforts with genuinely striking composition and staging. Meticulous shadows, highlights, and an overall boldness in both opaque paintings of characters and background paintings inadvertently cue it as an outing to remember, a story deemed so solid or prestigious that they sought to pour such time constraining details into this cartoon and this alone. Given the production value alone, it certainly must be a spectacle worth watching.

So, of course, the audience is instead treated to 8(!) minutes of obnoxious Hardawayisms, self indulgences, and weakness in writing and characterization. It wouldn’t be a cartoon with Ben Hardaway’s name on it otherwise.

In their final outing with The Pig, Hardaway and Dalton cast Porky as a plucky medieval villager eager to join the hunt to slay a giant. When the knights flee the castle in all of their cowardice, Porky is left behind to find a means of escape—but not before running into and having to babysit the giant’s equally giant baby.

Little incongruities that would soon grow thematic can be observed as early as the opening titles. The dramatic perspective of a castle’s towers looming in the background serves not only to rightfully flaunt an artistry so often missing in the Hardaway and Dalton cartoons, but to segue into a corny disclaimer about fictitious giants and the baseball team.

While certainly not the most egregious bit of incongruity—really, one of the more inspired ones, as the doors opening to reveal said disclaimer keeps the flow steady and the maneuver as a whole is striking visually—it’s a keen fore-bearer to the tonal imbalances peppering the entirety of the short. If only such incongruities could be as swift and comparatively confident as this one.

Likewise, the camera trucking into the castle entry as a means of transition is equally creative and bridges the scenes together well. Coming out of a fade and trucking back out into the regular register paint it so that the audience has fully immersed themselves into the cartoon, going in one and coming out the other. Sharp composition is maintained through a shot of a procession heading down the street.

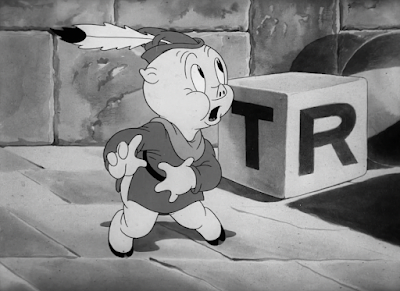

Low as the bar may be, props are in order for Porky’s introduction—upon spotting the march, he cautions a quick excited take before rushing downstairs (feather hat and all) and seeking out the hubbub. No meandering dialogue or needlessly conspicuous observation of “Oh beh-eh-boy! A process-eh-seh-sesh-eh-ehh—a processioneh-nuh-neh-neh—a m-mm-ma-eh-mar-mar-eh-mar—a parade!”

Unnecessarily elongated quirks manifest more in cinematic pacing rather than dialogue. If Porky spends a few seconds too long pausing outside his home and searching for the processional, shedding another excited take and rushing off to join, such is easier to dismiss than the aforementioned possibility.

A close-up shot of the various knights walking along touts sleek highlights on armor, gloves, weapons, etc. that is rather alien for the artistic standards of H/D. Boldness inherent to the black and white color scheming further draws out such shading.

Not only that, but by a miracle, Porky displays some semblance of character acting as he approaches one of the knights. His eager stride slows as he ogles at the knight, a childlike fixation and awe dominating his movements that feels natural and sincere rather than forced or obligatory.

His knocking on the knight’s armor is where further antitheses begin to wedge their way in. Still quite mild and not necessarily a detriment compared to future antics—mainly just a knob-headed dog poking his head out of the helmet backwards and speaking in a dopey voice later associated with Marvin the Martian. His “Well?” is a bit too abrupt—a stronger concentration of condescension oozes from its delivery compared to a “What?” Such a bluntly haughty tone isn’t alien to H/D’s filmography.

Upon Porky’s “Uh-weh-we-we-we-where’s everybody going?”, laden with awkward pauses between dialogue and stiff vocal direction, the pompous knight declares they’re going to get the giant. Usage of “the” indicates that said giant has been a scourge on the town beforehand, or at least has been commonly referenced. “A” is more vague and introductory.

No matter what direction the syntax follows, Porky is clueless regardless. A visual note, Porky is drawn surprisingly cute for Hardaway and Dalton’s standards; not so much explicitly, but he boasts a charm that is more apparent than his previous appearances.

This scene is a fine demonstration as such. Elongated highlights in the middle of his eyes convey a spark of youthful curiosity and arousal upon the realization of said giant, and the side mouth of phony calculated focus as he plucks a table leg and bangs it on the ground a few times—as though it’s something he’s seen other knights or superiors do—is a cute touch.

The next piece of action is the perfect demonstration of Hardaway and Dalton’s cartoons—or, rather, their shortcomings. It isn’t so much the establishment of a comedic tone that falters. In fact, the lightheartedness is encouraged. Rather, it’s that the giant is immediately established by singing in broken English to his equally giant baby; does rhyming “Up on the tree” and “I no can see” not tickle thine funny bone?

Such Hardawayisms could be pardoned had their been a stronger build-up to the giant’s presence outside of village gossip. Eery shots of the castle’s interior, foreboding rumbling and or grumbling, looming silhouettes… having that tangible suspense be broken through such childish endeavors would make a much stronger impact, even if the joke itself isn’t that funny.

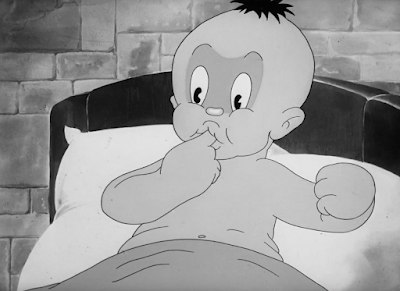

Here, there isn’t exactly much buildup exclusive to the giant outside of passing mention. Instead, the audience is forced to stomach the baby’s manly scatting solo in all of its obnoxious, grating misery glory.

Similar applies to the giant yawning not once, but twice in a sequence that nearly takes 10 seconds just to get him out of the picture. Baby is asleep, we need the giant to scram to allow the knights in, our dear viewers surely will not be able to identify such languor lest he yawn twice in equally drowsy animated draftsmanship.

Cutting back to a welcomingly cinematic composition of the knights approaching the castle’s façade notes a recurring theme through the short. It would be easier to dismiss this cartoon or take it at face value had it been filled with jokes and setups all along these lines—sporadic bursts of cinematography and less-one-dimensional-acting-than-usual almost seem like a tease. Knowing what Hardaway and Dalton could be capable of, what this cartoon could be capable of, and having it rectified through the typical obnoxious fodder is just as fascinating as it is aggravating and bewildering.

In any case, a dog faced knight obliges to the “DO NOT DISTURB” sign pasted on the castle doors, clearly unwilling to get on the bad side of the enemy. The caution in which all of the knights enter, slowly creaking the door open, tiptoeing into the castle, met with a chillingly vacant and vast shot of the palace’s interior all would have landed as a stronger catharsis to the giant’s care of his baby. A sign on the doors demanding quiet could be seen as intimidating, forceful, especially when the motive behind it is unknown—to have it all after the fact seems unnecessarily apparent. Such is the Hardawayian tendency to spell out every single detail to an unintentionally belittling degree.

Spelling out occurs with a shot of the giant, asleep, his snores blowing a sailboat out of a framed portrait above him. Perhaps it’s all a matter of taste, and to depict the giant as a hardworking father is to endear himself to audiences. Even then, the suspense shorn by the knights and in the filmmaking is incongruous to the attitudes of the giant, and not in a way that is exactly harmonious or funny. Contrasting attitudes isn’t a problem—confusion in filmmaking is.

Thankfully, some semblance of suspense and tension is rescued as the giant awakens from hearing a noise. Billy Bletcher’s low, steely “Who’s there?” reads as a statement more than a question; a strength in this case, as it conveys determination and apprehension.

His repetition of the same question is forceful, much louder. A dramatic down shot of all the knights not only unifies the two factions, bringing both the slayers and the (offscreen) enemy together and stringing the story together, but the gorgeously exaggerated staging in which the scene is composed invokes more anxiety, more fear, and makes the knights puny and powerless in scale.

Cowardice is quick to trump determination as all of the knights make a break for it. Dry brushing and a flighty flute glissando exaggerate the speed of their exit, which is refreshingly snappy for the typical sluggishness that dominates other H/D cartoons.

Save for one. Philosophies of the knights appearing extra insignificant upon the dramatic composition apply doubly for Porky, picking himself off the ground after being bowled over by his deserters. Consistently an underdog in Hardaway’s world, this particular instance seems the most sympathetic and potent yet thanks to tangible suspense, obstacles, and a general lack of meandering dialogue.

Gil Turner animates the adjoining sequence of Porky struggling to open the castle door after it shuts on him. Turner’s animation has a tendency to suffer from chronic weightlessness as is, and pairing said weightlessness in a scene that demands a realized kineticism and force behind it yields unsatisfactory results. Tugs on the door feel like aimless movement and fidgeting more than a struggle to save one’s life—frantic knocks share the same pedestrianism.

Similar to how the giant repeated “Who’s there?” twice, a booming “Anybody here?” receives the same treatment. Aimless repetition of dialogue is yet another Hardawayian trait (or, perhaps Tubby Millar, who wrote both cartoons)—much of Porky’s dialogue in Porky and Teabiscuit was filled with repeated phrases. Understanding he can’t flee, a shaking Porky tries his best to hide beneath the balcony on which the giant is standing.

Thus spawns an incredibly redundant—if not obnoxious—sequence of the giant making noise to catch the attention of his unknown visitor. Composition of the scene continues to impress, and the echoes radiating from his voice succinctly make him feel like a commanding, booming figure as well as exaggerating the emptiness of the castle as a whole. However, one “Yoohoo!” is plenty. Instead, the audience is met with 15 seconds of sheer redundancy filled with two “Yoohoo!”s, a “Hello!” and awkward pauses that are admittedly functional in their delivery but taxing nevertheless.

Deducing he is without any company, the giant heaves a signature Hardawayian shrug before making his departure.

Rod Scribner’s next piece of animation with Porky attempting to find an alternate exit bestows a primitive example of his signature “Scribner Teeth”; in the midst of his creeping, a tea kettle blasts him with a burst of scalding hot steam, sending him flying into the air and rushing out of the hallway.

Scribner’s drawings are both appealing and amusing, the distortions seen in his wild takes anomalous with the drawing style of the other H/D animators and thus a bit of a novelty. As such, somewhat thick timing on the sequence is a bit easier to withstand thanks to charming drawings. Even then—and this is not an issue exclusive to this scene—the lack of any sort of vocal exclamation from Porky lessens the impact.

Intents are somewhat muddled. Porky rushing through the castle as a natural reaction to the burn is logical in itself, but that he makes the decision to seek refuge in the baby’s crib and hides beneath the blankets seems to infer that his burst of energy is not from the burn, but to hide from an unknown entity he believes is hunting him.

That isn’t an issue in itself, but rather the lack of communication in the filmmaking; it doesn’t have to be obvious (as Hardaway has such a tendency to be), but it does feel more vague than is ideal. Props for the promptness of the chase—concealing his hiding beneath the crib and instead revealing it though a pan provides a clever surprise.

Likewise with revealing the lump in the crib to be both Porky and his giant baby companion. Rather than make a fuss, the infant only gawks, armed with signature blink lines from Dick Bickenbach. Porky’s posing as he spares a few glances (including one towards his company, entangled in his relieved oblivion) and pauses to relax are full of endearing charm and communicative acting despite a lack of dialogue. Such restraint is not taken for granted.

Similar applies to the warped expression of aggressive realization. Bickenbach’s distortions upon Porky’s wild take and rapid scramble take beneath the crib are welcome, animating on ones conveying a palpable urgency that still maintains clarity.

Clever staging and meticulous shading persists in a solid shot of Porky hiding beneath the crib, giant infantile fingers grabbing aimlessly in his direction. A strong discrepancy in values between light and dark embolden the composition, making the light shining through all the brighter and the darkness all the more thick. Likewise, more appealing poses are spawned from Porky as he attempts to dodge his visitor.

Here is where the cartoon takes a turn—giant or no giant, amusing as Porky taking a bite out of the baby’s finger is, it’s pretty out of character. Porky is the type to make facetious, off handed threats at children behind their backs (Porky’s Picnic), not act on them. While having the baby be a giant does warp perceptions a little, with Porky conveyed as the puny underdog, it still feels like an odd solution to a problem when said problem entails hiding from the baby in the first place. Amusing, sure, but odd to see such mean-spiritedness from Porky so early on.

Predictably, the baby doesn’t take kindly to this and throws Porky off after some irritating and belabored flailing that demands more energy and less accidental obnoxiousness.

Throbbing finger reminds the audience of Porky’s cruelty.

Even then, the infant doesn’t hold a grudge—the transition in tone is almost comedically jarring as he instead contentedly sucks on his assaulted finger, Mel Blanc heaving obnoxious, manly giggles in a matter of seconds.

Seguing into the next act of the cartoon, we follow Porky’s unwilling adventures in babysitting. Realizing that the baby’s smacking on the bed and causing Porky to propel into the air is an act of playfulness rather than a targeted attack, he agrees to play with him as a means of pacification. Stalling’s somewhat discordant, plucky and childish accompaniment of “You Must Have Been a Beautiful Baby” is fitting.

Enter a game of eh-puh-eh-peh-pih-Peas Porridge Hot that ends with the baby smacking Porky violently out of the crib. Dick Bickenbach’s animation of the patty cake game is cute, as is the not-so-subtle reference to the cartoon’s outro as Porky lands in a toy dream and tears a hole in it. A toy block landing on his head is a little excessive, but not to an egregious extent.

Egregiousness is delegated to dialogue instead. As wholly out of character the line “If you eh-wuh-we-wasn’t a baby, I’d eh-beh-be-bih-beh-bih-bust ya right ‘n the nose,” is coming from Porky, it’s so ridiculously absurd and needlessly aggressive that I have no choice but to be endlessly amused by it.

Porky could certainly be violent, but it is somewhat antithetical to his typically more demure nature of the late ‘30s, and said violence does not rub off on children in the handful of shorts that follow his misadventures in babysitting. That the baby is a giant is one thing, but the threats and finger biting feel somewhat overboard without a proper buildup to truly justify it. Still, it is admittedly amusing in a warped way.

Hardaway and company seemed to be so pleased with their drum callback that they repeat the same gag—this time initiated by the baby grabbing Porky’s snout and snapping him backwards.

Now, retaliation is delivered as Porky throws a ball at the baby and knocks him out of the crib, which feels slightly more violent than necessary.

Inconsistencies pepper this cartoon, and while they’re not something I exactly try to dwell on because I know the answer (“Why doesn’t Porky just try to leave the baby after he’s made it happy and content?” Answer: there would be no remainder of the cartoon), but such is worth mentioning. Whether it be the aforementioned question or even something as admittedly menial as “How was Porky able locate the bottle of milk so swiftly to pacify the baby’s cries?”, they do make the cartoon feel a little more discombobulated than what is ideal. At the same time, delegating 20 seconds to Porky trying to find a bottle would be taxing.

Upon finishing his bottle, gas tank metaphor keenly established, the baby erupts into cries. Further distraction measures follow the top of the bottle itself, where Porky pokes it into the bottle and pretends it popping back up was his own doing. Slow as the sequence grows, baby distracting measures growing more tedious, posing is solid and expressive. Clear silhouettes, continuous lines of action.

The audience has become accustomed to the patterns of the entire sequence by now—the baby’s attempts to do the same end with the rubber snapping him right in the face. His head tilts and anatomy as a whole maintain a solid construction and general visual appeal as a whole, which distracts from the tedium of the scene. Still, the rhythm and compositions of the scene as a whole drag and falter compared to the cinematography from before. It grows difficult to believe this is all the same cartoon.

More inconsistencies that are politely bothersome rather than actively detrimental persist. Why does Porky only bother to shush the baby now and show concern about waking up his dad when the baby has already wailed similarly twice before? Answer: to provide an explanation for the coming transition.

To pacify the baby once more, Porky suggests a lullaby on the condition that the baby goes back to sleep. A wordless, toothy grin from the infant answers in the affirmative.

Gil Turner returns to animate Porky playing the alphabet on a conveniently scaled toy piano. As to be expected, his singing is interrupted through strategic bouts of stuttering, getting stuck on every end of the verse—thankfully, it isn’t given too much of a highlight, as we have more important matters to dissect: a fully awake papa giant remarking on the cuteness of the situation, clearly unaffected by his trespasser.

Like the earlier incident with the tea kettle, Porky’s panic as he spots the giant and dives into a pile of toys could stand an added “YIPE!” or any sort of similar exclamation (irony of wanting MORE dialogue in a H/D cartoon duly noted.) Intent in emotions are clear—his fear is very much easy to read—but said fear feels somewhat artificial, less natural without the aid of an exclamation.

A rarity for Hardaway and Dalton, conversation between the giant and Porky occurs entirely in pantomime. The cautious blinks from Porky, the invitational attitudes from the giant, cautious head shakes no from Porky, a scowl from the giant… that, paired with the gentle music score accompanying their movements and the sculpted shadows on the giant are all reminiscent of Chuck Jones’ own cartoons. Quite a bit of praise given the difference in quality between directors.

Cue the chase sequence—the cartoon then reverts back to its cinematographic roots shed at the beginning to both a relieving and befuddling degree. While the chase is long winded at over a minute and could stand to undergo more exhilaration, gorgeous composition and unconventional camera angles are joyfully flaunted.

Likewise, a surprising degree of symmetry and parallels are delegated extra attention that is normally lost in the Hardaway shorts. A shot of symmetrical staircases has Porky descending and ascending them normally—the giant is tall enough to leap across them, a keen way of establishing such differences and power imbalance through unified obstacles. Likewise with the giant sticking his hands out of the castle windows and trapping Porky betwixt them; lovely parallel structure that is bold and almost rhythmic.

The end of the chase arrives in the form of the giant drinking the moat in which Porky has landed after falling from the tower. A beat in which the giant pauses to swallow the water is belabored rather than amusing, seeming more arbitrary and not worthy of halting the momentum of the climax for a joke that doesn’t even read like one to begin with. Momentary issues with the double exposure are flaunted as the giant is shot at half exposure for a few frames rather than the water, appearing like a ghost.

Adjacent unnecessary establishments follow Porky as he attempts to swim against the current; he ends up swimming on a mound of dirt for a seconds or two too long before he is retrieved by the giant, as if to ensure the audience positively digests the differentiation in physics.

Nevertheless, the ending is ironically my favorite portion of the cartoon (and not because it signifies the short’s end.) Rather, its strength; appealing animation, wordplay that isn’t incredibly taxing, and acting that isn’t wholly aggressive and instead feelings endearing and surprisingly natural.

Back at the toy piano, it’s revealed that Porky was able to pacify both giants through means of a lullaby. Now, his stuttering orchestrations are outfitted to fit his relief. Slight frustration is directed towards the writing—“Geh-ge-eh-gosh I’m glad they’d hit the hay, neh-now’s my chance to get away” would work much better with equal amounts of syllables and rhythm, but is instead shoehorned with the much more hasty and wordy “Neh-now my chance to make a getaway.”

Regardless, Porky uses the rare moment of quietude to escape—only to get caught. Pauses between Porky’s singing and the giant yelling “Hey, you!” feel unnatural and belabored as per usual, but the foreboding drumroll score in the background is a nice touch that adds further apprehension at Porky getting caught.

“Who, eh-muh-mih-me?” Dick Bickenbach wonderfully conveys Porky’s feigned, strained innocence—copious blinks and a toothy, open mouthed gawk are wonderfully disingenuous.

“Yes, YOU!”“Oh-oh, yes, eh, ‘U’.” The subversion is corny but clever, and Porky’s purposefully meandering dialogue has some of the most naturalistic vocal direction touted in the H/D shorts yet, particularly the nervous “Eh, heh. That’s right,” slurred under his breath. Likewise with a smooth save as he returns to the alphabet, transitions between dialogue swift as he jumps back into the chorus: “…ehb-eh-U and V, W and X, Y, Z…”

Same praises can be sung with his grouchy aside to the audience in tandem with the music; “Everything eh-seh-seems t’ happen to me.” Unlike the previous scenes where he threatens to “bust” the baby or even acts on it, his aggravation here is politely endearing and sympathetic rather than wholly aggressive.

“A, B, C, D, E, F, juh-jee-jee-eh-juh-jee-jee-jeh-jee-jee…”

“Shucks.” Great delivery, nice discordant accompaniment of his elbow landing against the toy piano, wonderful posing and surprisingly three dimensional acting as a whole as we iris out on Porky’s defeated glower, shared with both his captors and the audience.

Porky the Giant Killer is a very weird beast of a cartoon. So much so that it, at times, feels more like two separate shorts strung into one. While a considerable step down from Fagin’s Freshman in terms of coherency and even tolerance, it’s still an impressive cartoon visually, to the point that it buckles beneath its own weight. It is certainly understandable that maintains the level of cinematography in which this short peaks at would be difficult for 8 minutes straight, and isn’t at all expected, but the heavier slapstick portions involving Porky’s babysitting adventures feel much more stiff and flat and run of the mill in comparison to the beginning and end.

A general sense of lacking is what permeates when finishing the cartoon, hoping for more that wasn’t delivered. As mentioned before, it isn’t so much the comedic tone that’s an issue, but the application and balance—any suspense or tension is conveyed through environments or staging more than behaviors of the characters.

|

| From Eugene Waltz's Cartoon Charlie: The Life and Art of Animation Pioneer Charles Thorson |

Anticipation to the giant’s introduction is spread entirely through word of mouth—as such, there isn’t a very solid sense of danger, especially considering the docility of the giant. A lack of danger renders the stakes not as high, and the climaxes have a tendency to feel artificial as a result, the cartoon’s title misleading. There isn’t a solid enough contrast to buffer the giant’s fatherly tendencies.

With all of that said, this is one of the Hardaway and Dalton cartoons I like most. A guilty pleasure short, as it still suffers from many self indulgent Hardawayisms that serve as a detriment in the end—awkward pauses, gratuitous jokes that aren’t very funny to begin with, out of character acting, belabored pacing, confusion in delivery and coherency. Still, the cinematography is genuinely appealing, as is much of the drawing style. Likewise, in spite of some questionable acting decisions, Porky is comparatively well characterized.

With this being their last outing with him and second to last film overall, Porky has a level of dimension to his character seldom seen in his previous H/D cartoons. Though the finale is the greatest example of said depth, portrayed in an endearing and sympathetic way again alien to other shorts, his personality as a whole benefits from somewhat more inspired dialogue (not having half his lines be repeated as in Porky and Teabiscuit.) Boasting a generally cuter drawing style thanks to the likes of Dick Bickenbach and Rod Scribner contribute greatly to such a mission, as does an emphasis on solid acting and pantomime rather than buzzwords or constant stutter jokes.

Far from the best entry in the “Porky getting beaten up by babies” saga that’s been established for at least a few years now, it’s at least a more optimistic entry in the line of H/D films, obnoxious as it has a tendency to be. Its greatest vice is a general confusion in intent and a misunderstanding of how to mix cinematography and comedy well to an equally impactful degree. That the effort was made is appreciated, as the high points of the cartoon certainly are high, and to see such a heavy emphasis on staging, composition, and meticulous shading on characters from the typically flat stylings of Ben Hardaway is a great novelty.

It absolutely is an 8 minute long example of Hardaway’s self indulgences and how those grow obnoxious quite quickly, but, compared to other shorts in the same vain, provides greater incentives and is one I find myself struggling to completely disavow.

No comments:

Post a Comment